Response to Order of October 11, 1984

Public Court Documents

October 19, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Response to Order of October 11, 1984, 1984. b8fdcc0f-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/900c1cb9-2a96-46bd-8a10-c0335665a8f1/response-to-order-of-october-11-1984. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

o

IJNITED STATES

EASTERN DISTRICT

RALEIGH

MLPH GINGLES, et a1. ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

RUFUS L. EDMISTEN, QL.

al. ,

DISTRICT COURT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

DIVISlON

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

CIVIL ACTION NO.

81-803-CrV-5

of Election

Filing period opens at 12:00 Noon

Defendants.

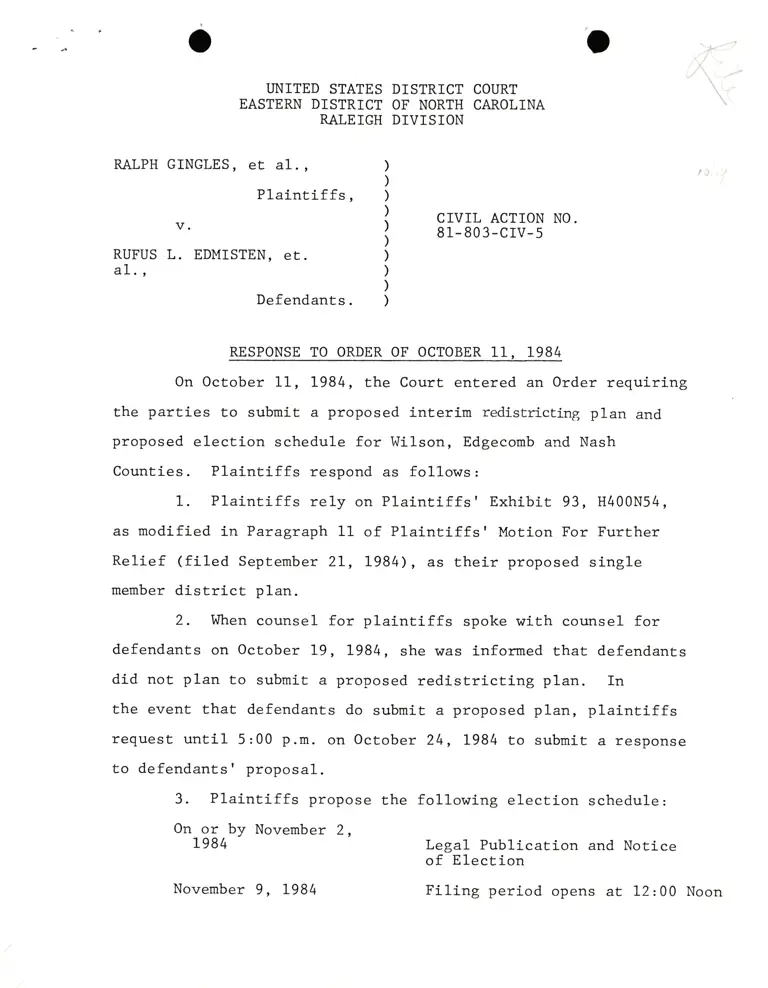

RESPONSE TO ORDER OF OCTOBER 11, 1984

On October 11, 1984, the Court entered an Order requiring

the parties to submit a proposed interim redistricting plan and

proposed election schedule for Wilson, Edgecomb and Nash

Counties. Plaintiffs respond as follows:

1. Plaintiffs rely on Plaintiffs' Exhibit 93, H400N54,

as modified in Paragraph 11 of Plaintiffs' Motion For Further

Relief (fi1ed September 2L, 1984), as their proposed single

member district pIan.

2. When counsel for plaintiffs spoke with counsel for

defendants on October L9, 1984, she was informed that defendants

did not plan to submit a proposed redistricting p1an. In

the event that defendants do submit a proposed plan, plaintiffs

request until 5:00 p.m. on october 24, L984 to submit a response

to defendants' proposal.

3. Plaintiffs propose the following election schedule:

On or by November 2,

L984 Legal Publication and Notice

November 9, 1984

-2-

Filing period closes at L2:00

Noon

Absentee voting

First Primary

Second Primary (if required)

General- Election

The canvass should be held in accordance with State 1aw

and the results are to be delivered to the state Board. of

Elections on the day the canvass is he1d.

This proposed schedule is based on the principle that

since the election cannot be held coincident with the November 6,

1984 general election, there will be better turnout and a better

opportunity to campaign the longer the time between November 6

and the primary election.

November 16, 1984

November 26-

December 11, 1984

December 18, L984

January 8, 1985

Jawary 29, 1985

rhis l1 a"y of OcJ.d4 , LgB4 .

Respectfully submitted,

d-;"*/

Fergusor-r, WEtt, Wa1-1_as & Adkins, p.A.

!u!te 730 East Independence pLaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carol_ina 28202

704/37s-846L

J. LEVONNE CHAMBERS

LANI GUINER

99 Hudson Street

16th F1oor

New York, New York 1001_3

2L2 / 219- 1900

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

r certify that r have served the foregoing Response to

Order of october 11, 1984 on all other parties by placing a

copy thereof enclosed in a postage prepaid properly addressed

\^rrapper in a post office or official depository under the

exclusive care and custody of the United States Postal Service

addressed to:

Mr. James tr'Iallace, Jr.

Deputy Attorney General

for Legal Affairs

North Carolina Department of Justice

Raleigh, North Carolina 27602

Mr. Arthur Donaldson

Burke, Donal-dson, Holshouser &

Kenerly

309 North Main Street

Salisbury, North Carolina 28L54

Ms. Kathleen Heenan McGuan

Jerris Leonard & Associates, P.A.

900 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1020

Washington, D.C. 20006

Mr. Robert N. Hunter, Jr.

201 West Market Street

Post Office Box 3245

Greensboro, North Carolina 27402

This l'{ day of October, L984.