NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Brief for Plaintiff in Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Committee on Offenses Against the Administration of Justice Brief for Plaintiff in Error, 1957. 52d5222e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/90ab2a89-512b-4840-b879-1e07795d0523/naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-v-committee-on-offenses-against-the-administration-of-justice-brief-for-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

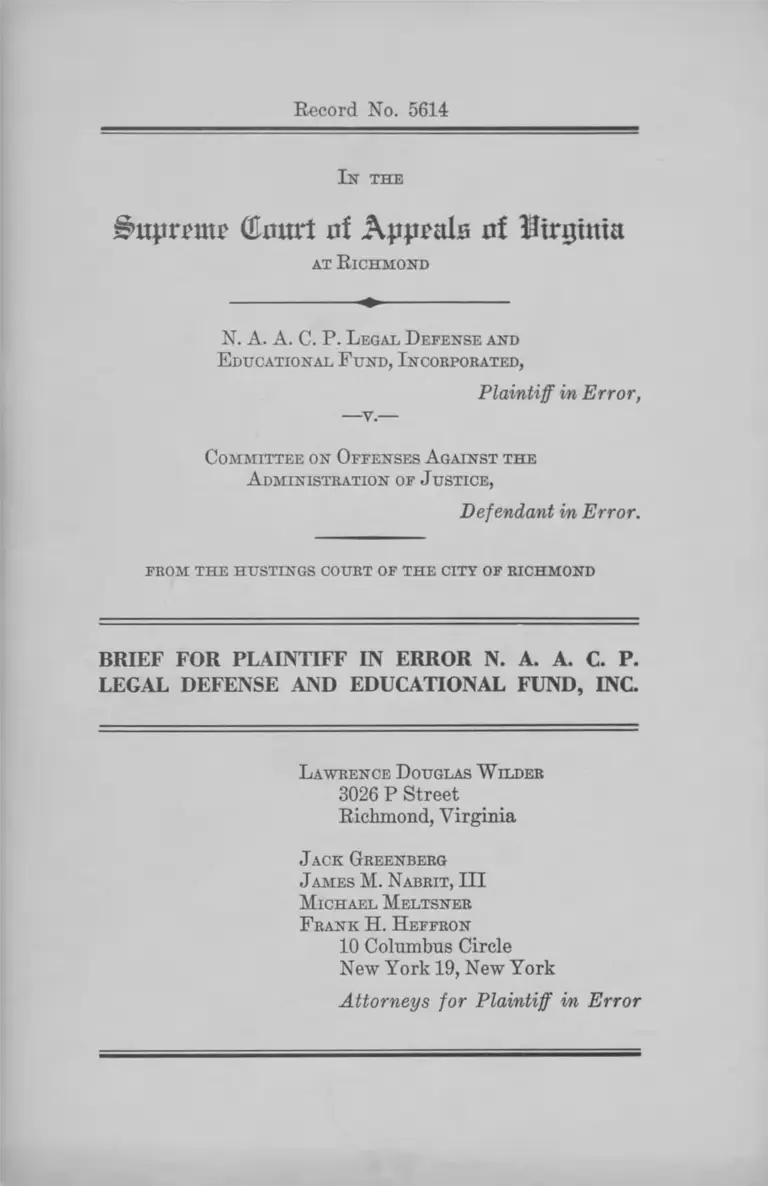

Record No. 5614

I n the

ii>uprmp GImtrt of A m alfi of Hirrjinta

at R ichmond

N. A. A. C. P. L egal D efense and

E ducational F und, Incorporated,

Plaintiff in Error,

—v.—

Committee on Offenses A gainst the

A dministration of Justice,

Defendant in Error.

FROM THE HUSTINGS COURT OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF IN ERROR N. A. A. C. P.

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

L awrence Douglas W ilder

3026 P Street

Richmond, Virginia

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael M eltsner

F rank H. H effron

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiff in Error

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Material Proceedings .............................. 1

Errors Assigned................................................................. 3

Questions Involved............................................................. 5

Statement of Facts ............................................................ 7

A rgument :

I. The Committee Is Not Authorized by Law

to Investigate the Matters Inquired Into hy

Interrogatory No. 1 ...................................... 14

II. The Rights of the Legal Defense Fund and

Its Contributors as Protected by the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United

States Are Infringed by the Failure of the

Committee to Clearly State the Scope of

Its Investigation and How Interrogatory

No. 1 Is Pertinent to That Investigation .... 18

III. Compelled Disclosure of the Names and Ad

dresses of the Fund’s Contributors Would

Violate Their Rights to Freedom of Asso

ciation and the Fund’s Property Rights as

Protected by the Constitution of Virginia

and the Constitution of the United States .... 20

IV. By Erroneously Excluding Evidence of the

Injury Which Would Result to Plaintiff in

Error and Its Contributors, the Trial Court

Denied Rights Protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and the Virginia Constitution 31

11

V. The Statute Creating the Respondent Com

mittee Serves an Impermissible Purpose

and Violates the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment ...................................................... 33

VI. The Exclusion of House Documents Nos. 8

and 9 From Evidence Was Erroneous and

in Violation of the Due Process and Equal

Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion, as Denying the Legal Defense Fund

the Opportunity to Prove the Improper

Legislative Purpose ...................................... 41

VII. The Committee’s Inquiry Arbitrarily Sin

gles Out Contributors to the Legal Defense

Fund and Similar Organizations for Tax

Investigation in Violation of the Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution ...................................... 43

VIII. Compelled Disclosure to the Committee of

the Names of the Fund’s Contributors

Would Be Contrary to Representations

Made to the United States Supreme Court

in Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167,

That Laws Compelling Similar Disclosures

Would Not Be Enforced Until Their Con

stitutionality Had Been Finally Determined 47

Conclusion ....................................................................................... 50

PAGE

T able of Cases

Adkins v. School Board of the City of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E. D. Va. 1957) .............................. 22

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516 ...........20, 21, 22, 26, 29, 33

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ...................................... 39

in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ...............33, 39

Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495.............................. 29

Currin v. Wallace, 306 U. S. 1 ...................................... 39

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 347 U. S. 483 .................................................... 33

Detroit Bank v. United States, 317 U. S. 329 .................... 39

Deutcli v. United States, 367 U. S. 456 ....................... 19

Gibson v. Florida Investigation Comm., 108 So. 2d

729, cert, denied 360 U. S. 919...................................... 27

Gibson v. Florida Investigation Committee, 372 U. S.

539 ............................................................20,23,24,27,28,30

Graham v. Florida Legislative Investigation Commit

tee, 126 So. 2d 133 ........................................................ 27

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 ............... 30

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167.............................. 21, 49

Kilbourn v. Thompson, 103 U. S. 168 .......................... 39

Lawrence v. State Tax Comm., 268 U. S. 276 ............... 33

McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U. S. 135 .......................... 39

PAGE

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 ...................20, 21, 22, 32,

33, 38, 42, 49

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415 ...........16, 20, 22, 29, 34, 39

NAACP v. Harrison, 202 Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55

(I960) ................................................16,20,27,34,43,45,49

NAACP v. Harrison (Cir. Ct. Richmond, Chancery

No. B-2880, 1962), reported unofficially in 7 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 864, 1216 ...................................................... 34

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v.

Harrison (Circuit Ct. City of Richmond, Chancery

No. B-2879, 1962), reported unofficially in 7 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 864, 1216 ................................................20, 23, 34, 49

IV

NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1958),

vacated on other grounds sub nom. Harrison v.

NAACP, 360 U. S. 167 ......................................22, 29, 35, 47

Pennekamp v. State of Florida, 328 U. S. 331 ...........29, 34

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 ................... 29

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147 .................................. 24

Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344 .......................... 3, 19, 22, 35

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 .............................. 20, 22, 26

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147 .................................. 16

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513.................................. 40, 45

Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U. S. 548 ............... 39

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 IT. S. 234 ....................... 17

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60 .................................. 20, 23

Washington ex rel. Oregon R. & N. Co. v. Fairchild,

224 U. S. 510................................................................. 33, 42

Watkins v. United States, 364 U. S. 178 ...........17,19, 39, 40

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183.............................. 16

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ................................. 42

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ....................... 44

S tatutes I nvolved

Acts of Assembly, Extra Session, 1956:

Chapters 31, 32 .................................. 22, 23, 34, 47, 48, 49

Chapter 33 ......................................................16, 22, 34, 41

Chapter 34 ...... ......................................................—.35, 36

Chapter 35 ........................................................... 22, 35, 41

Chapter 36 ...................................................... 16,22,27,34

Chapter 37 ................................................................... 36

Chapters 68, 70, 71 ....................................................22, 34

PAGE

V

Code of Virginia:

Sections 18.1-372-18.1-387, 18.1-380-18.1-387 ..23,47,49

Section 30-42 ...............3, 4, 9,11,14,15,18, 23, 37, 38, 39

Sections 30-49, 30-50 .............................. 10, 25, 36, 37, 42

Section 58-84.1 .............................................. 12,40,44,45

Sections 58-110, 58-111 .............................................. 12

Constitution of Virginia, §§11, 1 2 .............................. 5, 20, 30

House Joint Resolution No. 50, 1958 General Assembly 42

Other A uthorities

14 Am. Jur., Courts, §243, et seq........................................ 49

49 Am. Jur., States, etc., §42 .......................................... 17

5 Wigmore on Evidence, §1361.......................................... 32

5 Wigmore on Evidence, §1609 ... .................................... 32

PAGE

Record No. 5614

I n the

Caprone (tort nf Appeals nf Birputia

at R ichmond

N. A. A. C. P. L egal D efense and

E ducational F und, I ncorporated,

Plaintiff in Error,

—v.—

Committee on Offenses A gainst the

A dministration of Justice,

Defendant in Error.

FROM THE HUSTINGS COURT OF THE CITY OF RICHMOND

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF IN ERROR N. A. A. C. P.

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Statement of Material Proceedings

in the Lower Court

On May 25, 1961, defendant in error, Committee on Of

fenses Against the Administration of Justice, hereinafter

referred to as the Committee, sued out from the Clerk’s

Office of the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond (1)

a summons against National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People (NAACP), (2) a summons against

Virginia State Conference of NAACP Branches (Confer

ence) and (3) a summons against NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc. (Legal Defense Fund). Each

summons directed the organization addressed, on or before

June 23, 1961, to file with the clerk of the Committee sworn

answers to certain interrogatories requiring, inter alia,

2

disclosure of names of donors of $25.00 or more to the or

ganization. On June 23, 1961, the NAACP and the Con

ference filed with the Clerk of said Hustings Court their

joint Motion to Quash the summonses issued against them.

On June 23, 1961, the Legal Defense Fund filed with the

Clerk of said Hustings Court its Motion to Quash the

summons issued against it, and, specifically, the interroga

tory numbered one requiring the disclosure of names of

donors, the other information required by the interroga

tories addressed to the Legal Defense Fund having been

furnished to the Committee.

These Motions to Quash were heard together by said

Hustings Court on August 23 and 24, 1961. During the

hearing the court excluded certain evidence offered by the

movants, to which rulings exceptions were saved, and the

court reserved its ruling on the admissibility of certain

exhibits offered by the movants. By letter to counsel dated

September 25, 1961, the court ruled that movants’ exhibits

A and B were inadmissible; and on October 10, 1961, the

movants filed their exceptions to the exclusion of that evi

dence.

By letter from the court dated May 17, 1962, counsel were

advised of the court’s opinion, reached upon consideration

of the evidence and the briefs of counsel, that the several

motions to quash should be dismissed. By orders entered

June 22, 1962, the motions to quash were denied and the

movants were directed to provide to the Committee answers

to the said interrogatories. Due exception to each order

is noted therein and each order provides that its effect

is suspended for a period of ninety days from the date

of its entry and thereatfter until a petition for a writ of

error filed within such ninety-day period is acted on by

the Supreme Court of Appeals.

A petition for writ of error, filed by the Legal Defense

Fund in this Court on September 20, 1962, was granted on

December 3, 1962. A similar petition filed by the N. A. A.

C. P. was also granted on the same date.

3

The Errors Assigned

1. The court erred in rejecting petitioner’s claim that

the compulsory disclosure required by said interrogatory

numbered 1 did not violate the rights of petitioner and its

contributors to freedom of association and privacy of as

sociation as protected by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

2. The court erred in ruling that the inquiry contained

in said interrogatory numbered 1 was authorized by §30-

42(b) of the Code of Virginia.

3. The court erred in rejecting petitioner’s claim that

it had not been properly advised of the scope of the in

vestigation and of the connective reasoning by which the

said interrogatory numbered 1 is pertinent to the investiga

tion, thus depriving petitioner of rights under the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

4. The court erred in excluding evidence offered by peti

tioner tending to establish that the said interrogatory

numbered 1 was a part of a program by the committee

to subject petitioner and other organizations engaged in

furthering desegregation to special burdens in order to

deter persons from associating together to support litiga

tion to challenge racial segregation practices. This ex

cluded evidence was House Document No. 8 (marked for

identification as Exhibit A ), House Document No. 9

(marked for identification as Exhibit B), and also inquiry

of the witness James Thomson concerning testimony given

by him in Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344, 347 (1959) as

recounted in the Supreme Court opinion in that case. The

exclusion of this evidence denied petitioner due process of

law as protected by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

4

5. The court erred in excluding proffered evidence and

in restricting questioning of witnesses W. Lester Banks

and Thurgood Marshall concerning the harm to petitioner

and the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People in their fund raising activities which re

sulted from prior efforts by Virginia to compel disclosure

of the names of members and contributors, and concerning

the extent to which persons sympathetic with these or

ganizations have indicated that they were afraid or un

willing to be publicly identified as supporters of the

organizations because of the controversial nature of their

activities. The exclusion of this evidence denied petitioner

due process of law as protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

6. The court erred in rejecting petitioner’s contention

that the use of the Act creating the respondent committee,

e.g., §§30-42 to 30-51 of the Code of Virginia, to compel

the disclosures required by the interrogatory numbered 1,

deprives petitioner and its contributors of equal protection

of the laws in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

7. The court erred in declining to defer action on the said

interrogatory numbered 1 until after final determination

of the issue of whether such disclosures may be compelled

in other pending litigation between petitioner and officers

of the State of Virginia in which representations were made

on behalf of the Attorney General of Virginia that State

laws compelling these similar disclosures would not be

enforced until their constitutionality had been finally deter

mined.

8. The court erred in finding that the said interrogatory

numbered 1 was propounded in aid of a legislative purpose

which is not forbidden by the Due Process and Equal Pro

tection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

5

9. The court erred in finding that the disclosure sought

will not result in loss of rights secured to petitioner by the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States.

Questions Involved

I.

Whether the Committee is authorized by law to in

vestigate the matter inquix-ed into by Interrogatoi’y No. 1.

II.

Whether the Committee has failed to clearly state the

scope of its investigation and how the information sought

is pertinent to the investigation in violation of the rights

of the Legal Defense Fund and its contributors under the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

III.

Whether compelled disclosure of the names of con-

ti’ibutors to the Legal Defense Fund violates rights to free

dom of association protected by Section 12 of the Consti

tution of Virginia, and by the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States where the information sought bears little, if any,

relevance to the stated purpose for which the information

is sought; where the state can accomplish its aims without

invading freedom of association; and where the state has

failed to connect the alleged evil under investigation with

the Legal Defense Fund or its contributors.

6

Whether under the circumstances of this case compelled

disclosure of the names of contributors violates the Legal

Defense Fund’s property rights to foster and receive

support for its purpose and program as secured by Section

11 of the Constitution of Virginia, and by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution.

IV.

V.

Whether the trial court erroneously, and in violation

of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, excluded evidence

showing that compelled disclosure of the information

sought would visit harm upon the Legal Defense Fund

and its contributors.

VI.

Whether the statute creating the Committee serves an

impermissible legislative purpose in violation of the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

VII.

Whether the exclusion of House Documents Nos. 8 and

9 from evidence was erroneous, and in violation of the

due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, as denying

the Legal Defense Fund the opportunity to prove the im

proper legislative purpose.

7

VIII.

Whether the Committee’s inquiry arbitrarily singles out

contributors to the Legal Defense Fund and similar or

ganizations for tax investigation in violation of the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution.

IX.

Whether principles of comity and equity require that

Interrogatory No. 1 be quashed because of representations

by Virginia officials to the United States Supreme Court

that such information would not be required to be dis

closed pending the completion of certain litigation in the

state and federal courts.

Statement of Facts

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Incor

porated is a nonprofit membership corporation incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York and duly author

ized to function as a foreign corporation in the Common

wealth of Virginia (R. 68-69, Exhibits D, E). It operates

for the purposes of (a) rendering legal aid gratuitously

to Negroes suffering legal injustices by reason of race or

color, (b) promoting educational facilities for Negroes

who are denied the same by reason of race or color, and

(c) conducting research and publishing information con

cerning educational facilities and opportunities for Negroes

{Ibid.).

The Legal Defense Fund’s program is financed solely by

voluntary contributions from individuals and organiza

tions, in Virginia and elsewhere (R. 70-71), who, by their

contributions, associate to concert their efforts and to

8

safeguard the interests of individual citizens against un

constitutional color restrictions. Contributions to the Legal

Defense Fund are deductible on federal income tax returns

(R- 71).

The Fund operates with a “ staff in New York composed

of lawyers and research people and some of the lawyers in

other areas of the country for the sole purpose of rendering

legal assistance . . . when called upon by either the in

dividual or the individual’s lawyer where there is an ap

parent discrimination because of race or color . . . ” (E. 70).

The Fund no longer has a regional attorney stationed in

Richmond, as it formerly did, and the extent of its work

in Virginia is to cooperate with lawyers who have sought

its legal assistance (E. 70). The Fund has no salaried

employees in Virginia, and its only fund solicitation in the

State has been by letter (R. 70-71).

NAACP was organized under the laws of the State of

New York in or about the year 1911 as a “membership

corporation” and registered with the State Corporation

Commission of Virginia as a foreign corporation (E. 78).

It has approximately ninety unincorporated branches in

the State of Virginia which are under the control and

general supervision of the national association, being gov

erned by the national board of directors under policies

promulgated by the annual convention of the units of the

association (R. 78-79). The Conference is a voluntary un

incorporated association of the branches chartered by

NAACP in the State of Virginia (R. 79).

The basic aim and purpose of NAACP is to secure for

American Negroes those rights guaranteed them by the

Constitution and laws of the United States. In its Articles

of Incorporation, its principal objectives are described as

follows:

“ . . . voluntarily to promote equality of rights and

eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens

of the United States; to advance the interest of colored

9

citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and

to increase their opportunities for securing justice in

the courts, education for their children, employment

according to their ability, and complete equality before

the law.

“ To ascertain and publish all facts bearing upon these

subjects and to take any lawful action thereon; to

gether with any and all things which may lawfully

be done by a membership corporation organized under

the laws of the State of New York for the further

advancement of these objects” (R. 78).

The membership and fund raising campaigns of the

NAACP and the Conference are materially assisted by the

fact that these organizations encourage and give financial

support to the conduct of litigation attacking racial dis

crimination (R. 80-81). Neither organization represents

itself as eligible to receive contributions which may be

deducted from taxable income (R. 81).

Defendant in error, the Committee on Offenses Against

the Administration of Justice, was created by the General

Assembly in 1958. By Chapter 5 of Title 30 (§30-42 et seq.)

of the Code of Virginia, it is directed to investigate the

observance and enforcement of the laws of the Common

wealth relating to the administration of justice with partic

ular reference to the laws “ relating to champerty, main

tenance, barratry, running and capping and other offenses

of like nature relating to the promotion or support of

litigation by persons who are not parties thereto” (§30-

42(a)). The Committee is also authorized to investigate

the observance and enforcement of State income and other

tax laws as those laws relate to persons who seek to promote

or support litigation to which they are not parties con

trary to the statutes pertaining to champerty, maintenance,

barratry, and running and capping, etc. (§30-42(b)).

The Committee’s establishment in 1958 followed the ex

piration of two similar committees, the Committee on

10

Offenses Against the Administration of Justice and the

Committee on Law Reform and Racial Activities, both of

wrhich were organized in 1956 (R. 50, 59). At least two

members of the present Committee were members of the

previous committees (R. 54, 59). By the statute creating

it, the present Committee is given access to the records

of the previous committees (§30-50). The two earlier com

mittees cooperated with each other, used the same in

vestigators and exchanged information (R. 59-60).

The testimony of three members of the present Com

mittee showed that the present Committee and its two

predecessors have concentrated their investigations almost

entirely upon the NAACP and the Legal Defense Fund

(R. 42, 54-55, 60-62). This is also evident from the reports

of the two prior committees wdiich were excluded from

evidence (Exhibits A and B; R. 53) and from the report

of the present Committee which was admitted in evidence

(Exhibit C; R. 53).

The interrogatories propounded are in the following

form (R. 6-10) (the date December 31, 1956, having been

used in those addressed to NAACP (R. 7) and to the

Conference (R. 9) and the date December 31, 1957, having

been used in the interrogatory addressed to the Legal

Defense Fund (R. 8) ) :

“ Committee on Offenses Against the Administration

of Justice, a legislative committee of the Common

wealth of Virginia, calls upon [.......................] (here

inafter referred to as [ .......................]) to answer under

oath the following interrogatories:

“ 1. (a) State the name and address of each resident

of Virginia and of each firm, corporation and

enterprise situated or doing business therein

who or which, since December 31, 195...., has

made a donation of $25.00 or more to the

.......................; and

11

“ (b) State the time and the amount of each such

donation.

“ 2. (a) State the name and address of each recipient

of sums paid by the ....................... since De

cember 31, 195—. for legal services rendered

it or them or any other in the Commonwealth

of Virginia; and

“ (b) State the time and the amount of each such

payment, and the nature of the services for

which each payment was made.

“ The word ‘donation’ as used in interrogatory no. 1

shall be deemed to include, but shall not be limited to,

each payment of $25.00 or more received by the

.......................as a membership charge or fee, it being

understood that the ....................... in answering the

interrogatory is not required to state the purpose of

any donation.

“ These interrogatories are propounded pursuant to

§30-42(b) of the Code of Virginia, and answers thereto

are required to aid the Committee in determining what

donors, if any, have wrongfully recorded their dona

tions as allowable deductions in their income tax

returns filed with the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

what recipients, if any, have wrongfully failed to

show as income in such returns fees for legal ser

vices rendered in the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

Without waiving its objections, the Legal Defense Fund

answered Interrogatory No. 1 in part and Interrogatory

No. 2 completely (R. 17-23). All information requested by

Interrogatory No. 1 was given except the names and ad

dresses of donors. The Fund listed the date and amount

of each donation and the city from which it was received

(R. 18-20). In response to Interrogatory No. 2, the Fund

supplied the name and address of each person to whom

money had been paid for legal services as well as the time

and amount of each payment and the nature of the services

12

involved (E. 18-23). The Committee’s counsel acknowledged

the Fund’s cooperation stating: “ We are extremely grate

ful to you and your associates for answering all of our

interrogatories, except the ones referring to the names of

the contributors” (R. 75).

Approximately one million income tax returns are filed

in the State of Virginia each year (R. 67). Sixty percent

of these returns are “ short form” returns on which tax

payers take a standard deduction and do not itemize their

deductions (R. 67). Virginia law permits certain charitable

contributions to be deducted from gross income (Code

§58-81(m)), but contributions to an organization which

supports litigation to which it is not a party or in which

it has no direct interest may not be deducted under a 1958

amendment to the tax law (Code §58-84.1). Under this

provision the state tax department considers that con

tributions to the Legal Defense Fund are not allowable

deductions (R. 66). Individual income tax returns in Vir

ginia are filed with local revenue commissioners who audit

each return (R. 67) as required by Code §§58-110 and

58-111. All charitable contributions claimed as deductions

must be itemized, and local revenue commissioners are

under instructions to check for and disallow any improper

deductions (R. 67). In addition, all returns are forwarded

to the State Department of Taxation where a further audit

is made, though not of every return (R. 66, 109).

There is no evidence that any contributor to the

NAACP, the Conference, or the Legal Defense Fund

has claimed a deduction for such a contribution on a

Virginia tax return except for the testimony of the as

sistant to the director of the State Department of Taxation

that he had heard of one such instance (R. 66-67). There

is no evidence or claim that any contributor or donor has

committed any of the offenses against the administration

of justice.

13

Officials of the Legal Defense Fund fear that reprisals

would be taken against contributors if their names were

disclosed (R. 72). The organizations made a detailed proffer

of evidence they were prepared to present to demonstrate

the detrimental effect upon their membership and fund

raising campaigns of legislation passed in 1956 which

sought to require disclosure of the names of members and

contributors (R. 83). The court below struck the testimony

of the executive secretary of the Conference that individuals

have refused to identify themselves with the Association

despite their sympathy with its goal and that contributions

have been forthcoming after assurances were given that

the names of contributors would not be disclosed (R. 83-

84). It was proved that several persons anonymously join

or contribute to NAACP (R. 85).

Mrs. Sarah Patton Boyle, a resident of Albemarle County,

testified that she was a member of the NAACP; that

she worked in obtaining memberships and contributions for

the organization in the white community; and that she

was publicly identified with the NAACP (R. 98-100).

Mrs. Boyle stated that because of her identification with

the NAACP she had received anonymous threats on

the telephone including threats that her home would be

blown up; that a cross was burned fifteen feet from her

bedroom window at a time when her husband was away;

that someone sent an ambulance to her home “ for the dead

or mangled body of Sarah Patton Boyle” ; and that she is

frequently attacked by letters to the editor in the news

papers (R. 100-101). In addition, she mentioned that she

was subjected to personal social pressures and that one

man threatened her with economic pressure (R. 103).

14

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Committee Is Not Authorized by Law to Investi

gate the Matters Inquired Into by Interrogatory No. 1.

[See Assignment of Error No. 2 and Question Involved

No. I.]

Interrogatory No. 1 seeks the name and address of each

Virginia resident who has made a donation of $25 or more

to the Legal Defense Fund since December 31, 1957, and

the time and amount of each such donation (R. 8). It was

stated that the interrogatories were propounded “pursuant

to Section 30-42 (b) of the Code of Virginia, and answers

thereto are required to aid the Committee in determining

what donors, if any, have wrongfully recorded their dona

tions as allowable deductions in their income tax returns

filed with the Commonwealth of Virginia . . . ” (R. 8).

The statute mentioned, Section 30-42 (b), provides as

follows:

(b) The joint committee is further authorized to in

vestigate and determine the extent and manner in

which the laws of the Commonwealth relating to State

income and other taxes are being observed by, and

administered and enforced with respect to persons,

corporations, organizations, associations and other in

dividuals and groups who or which seek to promote

or support litigation to which they are not parties

contrary to the statutes and common law pertaining

to champerty, maintenance, barratry, running and

capping and other offenses of like nature.

Section 30-42(b), thus, only authorizes an investigation

into the tax affairs of persons and organizations who “ seek

to promote or support litigation to which they are not

parties contrary to the statutes and common law” pertain

15

ing to the various offenses specified in the last clause of

the subsection (emphasis supplied). Code Section 30-42(a)

which authorizes investigations relating to such offenses,

e.g., champerty, maintenance, barratry, running and cap

ping, etc., is not relied upon by the Committee to justify

the present investigation. It is submitted that the present

investigation is unauthorized because it is not an investi

gation of any persons or organizations who promote or

support litigation “ contrary to” the laws pertaining to

champerty, maintenance, barratry, running and capping,

etc.

While the interrogatory is directed to the Legal Defense

Fund, the Committee chairman expressly disclaimed that

its purpose was to investigate the Fund (R. 49, 118). He

stated repeatedly that the purpose of the question was to

determine if any persons who had made donations to the

NAACP and the Fund, had violated state income tax laws,

and that the Committee wanted their names in order to

check their tax returns (R. 47, 48, 118, 119). He stated

that it was not the present purpose of the Interrogatories

to determine whether the Legal Defense Fund or the

NAACP were themselves violating the tax laws, and that

this was not an investigation to determine if the laws on

barratry, champerty, running and capping, etc., were being

violated by the organizations (R. 48-49).

The Committee, having asserted a purpose to inquire

into the tax affairs of donors to the Fund, has failed to

establish that such donors are persons who it may investi

gate under Section 30-42(b). This is so because there is

no showing or claim that such donors promote or support

litigation to which they are not parties, “ contrary to” any

valid laws of the State. The Committee asserted that the

Fund and the NAACP violated the laws pertaining to the

unauthorized practice of law (R. 44), but has never as

serted that mere donors to the organization are persons

who have violated such laws. The assertion that the or

ganizations violated the laws was not based upon any de

16

termination by the Committee itself (R. 49), but upon the

decision of this Court in NAACP v. Harrison, 202 Ya. 142,

116 S. E. 2d 55 (1960) (R. 44, 49), that the organizations’

activities violated Chapter 33, Acts of Assembly, Ex. Sess.

1956. Since then, Chapter 33 has been held unconstitutional

in NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415. But neither the Com

mittee, nor any court, has ever determined that mere con

tributors or donors to these organizations acted “ contrary

to” any law. Indeed, this Court held in NAACP v.

Harrison, 202 Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55 (1960), that Chap

ter 36, Acts of Assembly, Ex. Sess., 1956, was unconsti

tutional under both the State and Federal Constitutions

stating that “ the appellants and those associated with them

may not be prohibited from contributing money to per

sons to assist them in commencing or further prosecuting

such suits, which have not been solicited by the appellants

or those associated with them, and channeled by them to

their attorneys or any other attorneys.”

If the organizations’ right to financially support litiga

tion is constitutionally protected, it follows a fortiori that

members of the public whose only connection with the

organizations is as donors, are not acting “ contrary to”

any valid laws relating to supporting litigation to which

they are not parties. Furthermore, even if the organiza

tions could be assumed to be violating such laws, it can

hardly be claimed that all their donors also acted in viola

tion of the laws without any evidence that they made

donations with criminal intent and with scienter or knowl

edge that they were supporting lawsuits in violation of

the laws. It is basic to due process, at least in the area

of free speech, that innocent “ unknowing” activity cannot

be thus indiscriminately classified as criminal conduct un

der notions of strict liability. Wieman v. Updegraff, 344

U. S. 183, 191; Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147. Where,

as here, the donors are unknown to the Committee, it ob

viously cannot claim that they have supported litigation

“ contrary to the statutes and common law.” Indeed, the

17

Committee’s chairman professed not to know whether con

tributors to the organizations were “ offenders” (R. 121).

Absent a showing that the Committee had some grounds

to believe that donors to the Legal Defense Fund are

acting “ contrary to” laws of the type mentioned in the

last clause of Section 30-42(b), it is manifest that the

Committee has no authority to investigate their tax affairs

under this statute.

Whatever the legislature’s power to authorize an in

vestigation, it is clear that the present inquiry into the

tax affairs of mere donors to the Fund is not authorized

by the law creating the Committee. “ The scope of the

power of the legislative committee and the matters which

it may investigate are referable primarily to the act or

resolution to which it owes its existence.” 49 Am. Jur.,

States etc., §42, p. 259. Particularly where the legislative

investigative process touches upon the highly sensitive

areas of free speech and association, it is important that

the delegation of power to an investigative committee be

clearly revealed in its charter. Cf. Sweezy v. New Hamp

shire, 354 U. S. 234, 245; Watkins v. United States, 354

U. S. 178, 198. That is not the case here, and thus the

inquiry is not authorized and should not be enforced by

the process of the courts.

18

n.

The Rights of the Legal Defense Fund and Its Con

tributors as Protected by the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States Are Infringed by the Failure of the Committee to

Clearly State the Scope of Its Investigation and How

Interrogatory No. 1 Is Pertinent to That Investigation.

[See Assignment of Error No. 3 and Question Involved

No. II.]

The argument set forth in Part I of this brief above states

the Fund’s contention that the Committee is not authorized

by Section 30-42(b) of the Code of Virginia to conduct an

inquiry into the tax affairs of persons who have contributed

money to the Fund. As previously stated, the Committee

attempts to relate the question to Section 30-42(b) (R. 8,

47-48). The order of the court below stated only that the

Interrogatory “was relevant to the respondent’s inquiry

and that the petition had been advised of that relevancy”

(R. 33).

It is submitted that since the information sought is not

plainly within the authority granted the Committee by

Section 30-42(b), a statement by the Committee that it

seeks the information pursuant to Section 30-42(b) (R. 8)

is singularly uninformative. Neither the Committee nor the

court below has stated the reasoning by wdiich the informa

tion sought is pertinent to any matter properly within the

investigative power of the Committee.

In addition, further confusion as to the purpose and

scope of the investigation is engendered by the Committee

counsel’s statement at the trial that “we are concerned

with whether they [the organizations] have committed the

offense of engaging in the unauthorized practice of law

which ties in with the purpose of the inquiry here” (R. 40).

A member of the Committee, Delegate Thomson, testified

19

that the purpose of the Interrogatory was “ a lot broader

than” to investigate the tax affairs of donors to these or

ganizations (R. 58), although he declined to elaborate on

what else the inquiry encompassed.

Under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, the Fund is entitled to be informed as to the scope

of the investigation and of the connective reasoning by

which the information sought is thought to be pertinent to

the subject being investigated. Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S.

344; Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178, 214-215;

Deutch v. United States, 367 U. S. 456, 467-469. In Scull

v. Virginia, supra, a case in which the Supreme Court re

versed the contempt conviction of one who had refused to

answer questions propounded by the Virginia Committee

on Law Reform and Racial Activities, the Supreme Court

made clear that pertinency was “ all the more essential when

vagueness might induce individuals to forego their rights

of free speech, press, and association for fear of violating

an unclear law” (359 U. S. at 353).

In Deutch v. United States, 367 U. S. 456, 467-468, the

Court, while deciding the case on statutory grounds, re

iterated that there was a due process requirement that the

topic under inquiry in legislative investigations be made

clear and that the pertinence of questions be demonstrated.

In the area of free speech and association, a vaguely de

fined investigation including questions not demonstrably

and indisputably pertinent, poses a special threat. Indi

viduals may be induced to give up their constitutional rights

to privacy of association through fear of violating the law

in defying a demand for information, even though the in

formation demanded is not pertinent to any authorized in

vestigation and its disclosure could not be compelled law

fully.

It is submitted that the failure of the Committee to state

clearly the scope of its investigation and the pertinency of

the question asked, is sufficient ground for quashing the

interrogatory.

20

m .

Compelled Disclosure of the Names and Addresses of

the Fund’s Contributors Would Violate Their Rights to

Freedom of Association and the Fund’s Property Rights

as Protected by the Constitution of Virginia and the Con

stitution of the United States.

[See Assignments of Errors Nos. 1 and 9 and Ques

tions Involved Nos. Ill and IV.]

It is now beyond debate that the right of freedom of

association, related as it is to free speech, assembly and

petition, is protected against state infringement by the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, Gibson v. Florida Inves

tigation Committee, 372 U. S. 539; NAACP v. Button, 371

U. S. 415; NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449; Bates v.

Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516; Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479;

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60; and by the Virginia

Bill of Rights (Constitution §12), NAACP v. Harrison, 202

Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55; NAACP Legal Defense and Edu

cational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison (Circuit Ct. City of Rich

mond, Chancery No. B-2879, 1962), reported unofficially in

7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 864, 1216. In Gibson v. Florida Inves

tigation Committee, 372 U. S. 539, at 544, the Supreme

Court reiterated the language of NAACP v. Alabama (357

U. S. at 402):

It is hardly a novel perception that compelled dis

closure of affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy

may constitute [an] . . . effective restraint on freedom

of association. . . . This Court has recognized the vital

relationship between freedom to associate and privacy

in one’s associations . . . Inviolability of privacy in

group association may in many circumstances be in-

dispensible to preservation of freedom of association,

particularly where a group espouses dissident beliefs.

21

This record reveals that compelled disclosure of the

names of those contributing funds to the Fund and the

NAACP would work a significant interference with the

freedom of association of the organizations’ donors,1 as

well as with the organizations’ interest in their continued

existence and the execution of their programs and policies.

Here, as in Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 524, there

was uncontroverted evidence that public identification of

persons in the community with the organization had been

followed by harassment and threats of bodily harm (R. 99-

101). See NAACP v. Alabama, supra. Numerous other

attempts by the Fund and the NAACP to show that govern

mental attempts to identify supporters resulted in loss of

support due to fear of reprisals were excluded by the trial

court (R. 82, 83, 84, 86, 88, 89). The Director of the Legal

Defense Fund did testify that reprisals would he taken

against contributors if their names were disclosed (R. 71,

72, 76). It was brought out that some persons anonymously

join or contribute to the NAACP (R. 85, 90, 91, 105), but

the trial court refused to let a witness testify as to state

ments to him that this was a result of fear of reprisals

(R. 86). The evidence shows that some persons have re

fused to identify themselves with the NAACP despite their

sympathy with its goals, and that some contributions have

been forthcoming only after assurances were given that the

names of contributors would not be disclosed (R. 88, 89).

The trial court refused to allow evidence showing that in

come received by the NAACP and the State Conference in

creased after court decisions made the threat of disclosure

of members less imminent (R. 83). It was established that

public hearings and other occasions upon which an indi

vidual’s affiliation with the NAACP became a matter of

public record have been followed by abusive phone calls,

1 Plaintiff in error is the appropriate party to assert these rights,

since to require them to be claimed by its donors “would result in

nullification of the right at the very moment of its assertion,”

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 459, 460 ; Bates v. Little Rock,

361 U. S. 516, 524, n. 9.

22

bomb threats, a cross burning and similar incidents (R.

100-01) .

In addition to this uncontroverted evidence of com

munity hostility and reprisals against those publicly affili

ated with plaintiff in error, the history of hostility and re

sistance in Virginia to the organization and the goals which

it espouses are a matter of public record. High officials of

the State have expressed their attitude of resistance to

desegregation and hostility to persons and organizations

working to support desegregation. This history is well

known and has been repeatedly recounted in judicial opin

ions. See NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503, 506-17 (E. D.

Va. 1958), vacated on other grounds sub nom. Harrison v.

NAACP, 360 U. S. 167; Adkins v. School Board of the

City of Newport News, 148 F. Supp. 430, 434-436 (E. D.

Va. 1957); Scull v. Virginia, 359 U. S. 344, and see, gener

ally, Virginia Acts, 1956 Extra Session, Chapters 31-37,

56-71. As stated by the United States Supreme Court in

NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 435, “We cannot close our

eyes to the fact that the militant Negro civil rights move

ment has engendered the intense resentment and opposition

of the politically dominant white community.” Without a

doubt, in Virginia, the NAACP, the Conference and the

Legal Defense Fund are organizations espousing a contro

versial, dissident and unpopular cause. Exposure of affilia

tion and support can have no other result than to affect

adversely the ability of plaintiff in error and its supporters

to pursue their collective effort to work for goals they

clearly have a right to advocate.2 Shelton v. Tucker, 364

U. S. 479; NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449; Bates v.

Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516; NAACP v. Button, 371 U. S.

415.3

2 It is unimportant that this repressive effect is, in part, the

result of private attitudes and pressures, if governmental action

in forcing disclosure inhibits freedom of association, NAACP v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. at 463 ; Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. at 524.

3 Counsel for the respondent committee suggested to the Court

below that Rule 14 of the Committee protects against public dis

23

Of course, in the final analysis the right to privacy of

association need not necessarily turn on the popularity

or unpopularity of the group involved. As Mr. Justice

Douglas stated in a concurring opinion in Gibson v. Florida

Investigation Committee, 372 U. S. 539, 570, “ whether a

group is popular or unpopular, the right of privacy implicit

in the First Amendment creates an area into which the

Government may not enter.” It may be noted that the hold

ing in Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60, that an ordinance

requiring handbills to disclose the name and address of

the distributor or printer was invalid, did not rest upon any

determination that the group involved was an unpopular

one. The handbills involved in Talley urged a boycott in

support of equal employment rights for minority groups in

California (362 U. S. at 61).

Due regard for the constitutionally protected right of

freedom of association, and for the obvious injury which

would result from the disclosures sought here, compels the

conclusion that the State has not justified invasion of as-

sociational privacy in this case. The Committee stated that

the names of donors were sought pursuant to Virginia

Code §30-42(b) and that they were “ required to aid the

Committee in determining what donors, if any, have wrong

fully recorded their donations as allowable deductions in

closure of the information sought. That rule merely provides:

“No committee records, reports or publications, or summaries

thereof shall be made or released to others without the approval

of the Chairman of the Committee or a majority of its members.”

(R. 116). Thus, a simple vote of the Committee or even the

decision of its chairman can authorize publication of the names

of donors. The chairman stated that he did not know if the names

would be made public (R. 119). Even if the Committee should

not wish to publish donors’ names, there is no assurance that the

Legislature would not make them public, particularly in light of

previous legislative attempts to do so. See Chapters 31 and 32,

Acts of Assembly, Extra Session, 1956, codified as Sections 18.1-372,

et seq. and 18.1-380, et seq. These laws were held invalid in NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund v. Harrison (Circuit Ct.

City of Richmond), 7 Race Rel. L. Rep. 864, 1216.

24

their income tax returns filed with the Commonwealth of

Virginia. . . . ” 4 In order to sustain the compelled dis

closure sought, justification for requiring the names of

contributors must be found in “ the substantiality of the

reasons advanced in support of the regulation of the free

enjoyment of the rights.” Gibson v. Florida Investigation

Committee, supra at 545; Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147,

161. This Court must, therefore, appraise the Committee’s

explanation that its purpose was to learn “what donors, if

any, have wrongfully recorded their donations as allowable

deductions,” in light of the constitutional rights asserted

by the Fund (R. 9).

Analysis reveals how insignificant is the State’s pecuniary

interest in learning the names of these contributors. Con

tributions received by the Fund from Virginia in amounts

of $25 or more totalled $16,610.20 for the years 1958, 1959,

1960 and part of 1961 (R. 17-20). Assuming that every

contributor to the Fund itemized his deductions and claimed

a deduction for his contribution every year, and assuming

that every contributor was in the highest tax bracket of

5% (Code §58-101), and assuming arguendo that deduc

tion of contributions to the Fund is improper, the State

Avould have lost a grand total of $830.51, through such tax

deductions over the 3x/o year period. This is obviously an

unrealistically high figure, Avhen it is considered that 60%

of taxpayers use the optional standard deduction (R. 67),

and that there is no reason to believe that any of the Fund’s

donors claimed such deductions properly or improperly.

Any actual lost revenue is obviously a trifling amount.

Viewed against the gravity of the injury to contributors

if their names are disclosed, the financial interest of the

State is insignificant.

4 Plaintiff in error supplied all other information sought includ

ing the amount contributed by each donor (each donor being as

signed a number), the city of residence of each donor, and fees

paid for legal services rendered in the Commomvealth (R. 17-23).

25

But more fundamental is the fact that all of the informa

tion needed to determine which, if any, donors have de

ducted contributions to the Fund on their tax returns is

already in the possession of the State— on the tax returns

themselves. Any donors who have claimed such deductions

have thus voluntarily disclosed their support of the Fund,

but the Fund has no way of knowing which, if any, donors

have done this. But the State can find this out directly by

examining the returns which are in the State’s own tax

files and which are available to the Committee (R. 29;

Code ^30-49). Despite the fact that all returns have al

ready been checked by the local revenue commissioners and

that many have again been checked by the State tax de

partment auditors, the Committee asserts that it wants to

check them again. If it so chooses, the Committee can

examine the returns on file. The Committee has attempted,

but plainly failed, to show that such a check by it would

be impracticable (R. 107-109, 111-114).° Sixty percent of

the one million tax returns filed each year in Virginia are

on a one-page short form and could be disregarded at a

glance in such a check since they involved taxpayers using

the optional standard deduction (R. 113-114). A check of

the other forty percent of the returns for this information

would only require a mere glance at the appropriate line

on the return to determine if the Legal Defense Fund was

mentioned. This could obviously be done by anyone who

can read the name of the Defense Fund and would not

require a skilled auditor. 5

5 When questioned by counsel for the Committee, an official of

the State Department of Taxation testified that it would take ap

proximately two years to check all personal and corporate returns

for the period since January 1, 1957 (R. 107, 108), but on cross

examination it was revealed that his estimate was based solely on

the experience of an auditor making a complete audit of tax re

turns (R. 112) including checking every item on the return for

accuracy (R. 112). When asked if he had made any estimate of

the amount of time it would take an auditor to check returns

merely to see if a contribution was made to a given organization,

he testified that he had not (R. 112).

26

The essential point is that the Committee has the means

of obtaining the information which it says that it needs

without requiring the broad disclosure of the names of

all of the Fund’s donors and without invading the privacy

of their association. Thus, the demand made is plainly un

necessary to the development of the information which the

Committee states that it wants.

“When it is shown that state action threatens signifi

cantly to impinge upon constitutionally protected freedom,

it becomes the duty of this Court to determine whether the

action bears a reasonable relationship to the achievement

of the governmental purpose asserted as its justification.”

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 525. Given the insig

nificant monetary amount involved, the fact that the State

has already checked and in some cases double checked the

tax returns for such deductions; and the fact that the State

has the information it says it wants in its files, it is evident

that the Committee has not asserted an interest sufficiently

substantial to justify abridgement of the constitutional

rights of the Fund and its donors.

The application of the principle to this case is well illus

trated by Shelton v. Tucker, supra, where a state law sought

to compel teachers to disclose every organization to which

they belonged in order to assist local school boards to

determine the suitability of teachers. It was not disputed

that some of the information sought might serve a legiti

mate governmental purpose (364 IT. S. at 485). But, the

Supreme Court nevertheless ruled that the law was invalid

stating:

Though the governmental purposes be legitimate and

substantial, that purpose cannot be pursued by means

that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when

the end can be more narrowly achieved. The breadth

of legislative abridegement must be viewed in the light

of less drastic means for achieving the same basic pur

pose (364 U. S. at 488; and see authorities cited there

in).

27

For much the same reason, this Court struck down Chapter

36, Acts of Assembly, Ex. Sess., 1956, in NAACP v. Har

rison, 202 Va. 142, 116 S. E. 2d 55 (1960); cf. Gibson v.

Florida Investigation Comm., 108 So. 2d 729, cert, denied

360 U. S. 919; and Graham v. Florida Legislative Investiga

tion Comm., 126 So. 2d 133.

In addition to its failure to use “ less drastic means” for

the attainment of its purpose, the Committee has failed

to carry its burden under the rule of Gibson v. Florida

Investigation Comm., 372 U. S. 539, 546, of convincingly

showing a substantial relation between those whose pri

vacy is invaded and a subject of overriding and compelling

state interest. Gibson, supra, is in principle indistinguish

able from this case. There, a Legislative Committee of the

State of Florida sought to determine the extent of com

munist influence in the NAACP by ordering a branch presi

dent to consult membership records himself and, after

doing so, to inform the Committee wdiich, if any, of the

persons identified as communists wrere members of the

Branch. The branch president refused and was held in

contempt. The Supreme Court reversed on the ground that

the Committee had failed to show a sufficient “ nexus” or

“ foundation” establishing a connection between the NAACP

and the evil to be investigated, namely, communist sub

version (372 U. S., at 554-558). Despite evidence that 14

communists or members of communist “ front” organiza

tions had been affiliated with the Branch and that at least

one contribution had been made to the Branch by a com

munist (and see generally 372 U. S. at 550-554), the Court

held the legislative interest insufficient to overcome the

fundamental rights of associational privacy.6

6 An earlier attempt by the legislative committee to compel

production of the entire membership list was quashed by the

Florida Supreme Court, 108 So. 2d 729, cert, denied 360 U. S.

919, the Court stating that the Committee could, however, compel

the custodian of the records to bring them to the hearing and refer

to them. It was a refusal of this latter request by the branch

president which the United States Supreme Court upheld (372

U. S. 539).

28

In contrast, the “ slender showing” (372 U. S. at 556) of

a connection between the organization and the evil to be

investigated in the Gibson case, supra, is far stronger than

anything in this record. Here, the evil under investigation

is persons who take tax deductions for contributions to the

Fund. This record is barren of evidence showing any his

tory or practice of improper deductions of contributions

to the Fund. The only reference in this record to any case

of deduction of contributions is the testimony of an official

of the State Tax Department that he had “ heard” of one

instance where a person had claimed a deduction which

was later disallowed (R. 66, 67). Whether this contribution

was to the NAACP, the Conference or the Legal Defense

Fund, was not specified. There was no evidence that deduc

tion of gifts to the Fund is a special problem in the collec

tion of taxes, or that donors to the Fund have any pro

pensity to make improper deductions. If the showing in

Gibson connecting the organization with the evil to which

the questions pertained was an insufficient “ nexus” or

“ foundation” to overcome the right of privacy, then a

fortiori there has been no sufficient “ nexus” or “ founda

tion” shown here. The mere possibility, unsupported by

any factual showing, that the organization and the “ evil”

may be connected cannot be enough to meet the Gibson

test, for the mere “possibility” of such a connection was

clearly present in that case. Absent some proven factual

connection between improper tax deductions and contribu

tions to the Fund, the strong interest in maintaining as-

sociational privacy must prevail. This conclusion is all the

more cogent in this case because here the evidence of a

connection between the Fund and improper tax deductions

by its donors, if such evidence exists, is all within the cus

tody and control of the Commonwealth in the form of tax

records.

Disclosure of the information sought not only impairs

contributors’ rights to associational privacy, but it also

abridges the organization’s property rights as secured by

the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

29

the Constitution of the United States and by the Virginia

Bill of Rights (Constitution of Virginia, §11). The right

of the Fund to receive and solicit contributions to support

its program free from invidious regulations is protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment. Pierce v. Society of Sisters,

268 U. S. 510, 535, 536. See also, NAACP v. Patty, 159

F. Supp. 503 (E. D. Va. 1958), vacated on other grounds,

sub nom. Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167; NAACP v.

Button, 371 U. S. 415. In the Button case, supra, it was

recognized that the activities of an organization support

ing litigation as a means of achieving the lawful objec

tives of racial equality were not a mere technique for

resolving private differences but were in the realm of pro

tected Fourteenth Amendment activity. As stated by the

Court, “ . . . under the conditions of modern government,

litigation may well be the sole practicable avenue open to

a minority for redress of grievances” (371 U. S. at 430).

Without more of a showing of a compelling governmental

interest than is revealed by this record, the Committee

cannot force disclosure of information calculated to destroy

the organization’s ability to sustain its program. Once it

is granted that for the minority group represented by the

Fund “ association for litigation may be the most effective

form of political association,” NAACP v. Button (371

U. S. at 431), the conclusion follows inescapably that gov

ernmental action which seriously interferes with the ability

of such an “ association” to raise funds to operate impairs

freedom of speech. That plaintiff in error is a corpora

tion and not a natural person does not alter this result.

“ Freedoms such as these are protected not only against

heavy-handed frontal attack, but also from being stifled

by more subtle governmental interference.” Bates v. Little

Rock, 361 U. S. 516, 523. See Pennekamp v. State of

Florida, 328 U. S. 331 and Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343

U. S. 495, cases holding that First Amendment rights

apply to corporations. Indeed, the Supreme Court has

struck down tax legislation which impaired the rights of

corporations whose business was the dissemination of in

30

formation on free speech grounds. Grosjean v. American

Press Co., 297 U. S. 233. Implicit in recent decisions up

holding the right of associational privacy is the finding

that rights to property as well as rights to freedom of

speech and association may not be abridged by the states

in the absence of a compelling state interest. No such

interest has been shown here.

Rights to free association are “ fundamental and highly

prized and ‘need breathing space to survive,’ ” (Gibson,

supra, 372 U. S. at 544). In view of the slight interest of

the Committee in the information sought from the Fund,

as compared to the serious consequences to the associa

tional and property rights of the Fund and its donors if

the information is disclosed; the ability of the Committee

to obtain the facts and fulfill its asserted purpose without

infringing freedom of association; and the complete failure

of the Committee to connect the Fund or its donors with

the “ evil” of wrongful tax deductions, the Committee’s

inquiry must be held to be a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and

the Virginia Bill of Rights (Constitution of Virginia, §§11,

12) .

31

IV.

By Erroneously Excluding Evidence of the Injury

Which Would Result to Plaintiff in Error and Its Con

tributors, the Trial Court Denied Rights Protected by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and the Virginia Constitution.

[See Assignment of Error No. 5 and Question Involved

No. V .]

The trial court repeatedly refused to permit plaintiff

in error to demonstrate the effect disclosure of the names

of donors would have on persons desiring to support the

organization and the organization’s attempt to raise funds

(R. 72-74, 81-87, 99, 105).

The court sustained objection to this question: “Will

you give us an account of how, if at all, the several efforts

of the different agencies of the Commonwealth of Virginia

since 1956 to obtain the names of the members and con

tributors of the Association have at one time or another

affected the success of the membership and fund raising

campaign?” (R. 81). The stated purpose of the question

was to show that disclosure would work financial harm and

loss to the organizations (R. 82) and plaintiff in error

proffered testimony to the effect that 1956 legislation aimed

at requiring disclosure of the names of the members and

contributors had a detrimental effect upon the membership

and fund raising campaign which was relieved after the

federal court declared that menacing legislation invalid

(R. 83).

The court also sustained objection to testimony offered

to show that a considerable number of people decline to

support the organization for fear of public reprisals re

sulting from disclosure. The court struck out testimony

that individuals have refused to identify themselves with

32

the Association, as members of the Association, but have

been and are very sympathetic to the objectives of the

Association and very willingly make contributions to the

Association if they are assured that these contributions

will not become a matter of record (R. 73, 86, 87).

In excluding this evidence as irrelevant or as hearsay,

the court rejected the only means by which the plaintiff

in error could demonstrate the adverse effect of disclosure

of the information sought on both the property rights of

the organization and the associational rights of its con

tributors. Obviously, for donors who wish to be anony

mous to testify about their reason for so wishing would

require a surrender of the very constitutional right of

privacy in association which they seek to assert. Cf.

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449, 459, 460.

The hearsay rule is no bar to the introduction of this

evidence. First, one purpose of the evidence was to estab

lish that individuals who desired to support the organiza

tion were inhibited by fear of reprisal if their support

were a matter of public knowledge. As disclosure would

inhibit such persons from giving support, because of their

fear, the fact that their fear might be groundless is irrele

vant to a showing that disclosure would decrease contribu

tions. Statements offered to show belief in a proposition

rather than the truth of the proposition are not hearsay

at all. 5 Wigmore on Evidence §1361, p. 2. Second, an

other purpose of the evidence was to establish the com

munity attitude toward the organization and its supporters.

There is no other way to establish community attitudes

than to ask persons what others have told them. 5 Wig-

more on Evidence §1609, p. 479. In such a situation a

trial judge sitting without a jury should permit the intro

duction of evidence and consider its character as going

to the weight to which it should be accorded. Finally, the

evidence excluded consisted of so-called “ constitutional

33

facts”—facts upon which the application of the guarantee

of freedom of association depends. In both NAACP v.

Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 and Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U. S.

523, the United States Supreme Court relied on evidence

that disclosure would work significant interference with the

organization and its members due to fear of community

hostility and reprisal. The exclusion of this evidence de

signed to protect Fourteenth Amendment claims is in itself

a denial of due process contrary to that Amendment

(Washington ex rel. Oregon R. & N. Co. v. Fairchild, 224

U. S. 510. Cf. Lawrence v. State Tax Comm., 286 U. S.

276), for how else could the rights protected by the Consti

tution be vindicated.

V.

The Statute Creating the Respondent Committee

Serves an Impermissible Purpose and Violates the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

[See Assignment of Error No. 8 and Question Involved

No. VI.]

The statute creating the respondent Committee, far from

serving any valid and substantial governmental purpose,

was part of a legislative program designed to preserve

racial segregation and obstruct the constitutionally pro

tected activities of the Legal Defense Fund, the NAACP,

and the Conference.

Following the Supreme Court cases outlawing segrega

tion in public schools, Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483, which were argued by lawyers associated with

the Legal Defense Fund and the NAACP, and one of which

arose in Virginia (Davis v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 347 U. S. 483), the General Assembly

adopted several measures to prevent the implementation of

the Court’s decree. Meeting in Extra Session on December

34

3, 1955, it enacted a bill enabling the voters to authorize a

constitutional convention on the question of tuition pay

ments for private schooling. During the regular session of

1956, it resolved “ to take all appropriate measures hon

orably, legally and constitutionally available to us, to re

sist this illegal encroachment [the Supreme Court decision]

upon our sovereign powers. . . . ” Acts 1956, pp. 1213, 1214.

Later in 1956, an Extra Session was held, at which were

passed a law preventing state support of integrated schools

(Chapter 71), the Pupil Placement Act (Chapter 70), and

a law providing for the closing of integrated schools

(Chapter 68).

Included in the package of “massive resistance” laws

passed at the Extra Session of 1956 were two statutes

requiring registration of a narrowly defined class of per

sons or groups (Chapters 31, 32). Compliance with these

statutes by the NAACP and the Fund would have entailed

disclosure of the same information as is sought by the

Committee’s interrogatories in the instant case, and these

statutes have been held unconstitutional by both the fed

eral courts, NAACP v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503, vacated on

other grounds, Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167 (1959),

and the Virginia courts, NAACP v. Harrison, Cir. Ct. Rich

mond, Chancery No. B-2880, August 31, 1962; NAACP Le

gal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison, Cir.

Ct. Richmond, Chancery No. B-2879, August 31, 1962, as

an infringement of free speech.

Another element of the legislative campaign against the

NAACP and the Legal Defense Fund was the passage in

the 1956 Extra Session of statutes on barratry (Chapter

35), maintenance (Chapter 36) and running and capping

(Chapter 33). All have been held unconstitutional, NAACP

v. Harrison, 202 Va. 142 (1960) (Chapter 36); NAACP v.

Button, 371 U. S. 415 (1962) (Chapter 33); NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund v. Harrison, Cir. Ct. Rich

mond, Chancery No. B-2879, August 31, 1962; and NAACP

v. Harrison, Cir. Ct. Richmond, Chancery No. B-2880, Au

35

gust 31, 1962 (Chapter 35). Judge Soper in NAACP v.

Patty, supra, said that these three laws “ are new in the

statute law of the state and are essential parts of the plan

which deprives the colored people of the state of the as

sistance of the Association and the Fund in the assertion

of their constitutional rights” (159 F. Supp. at 530). If

further demonstration of this truism is needed, it is sup

plied by the acknowledged (R. 56) statement of Delegate