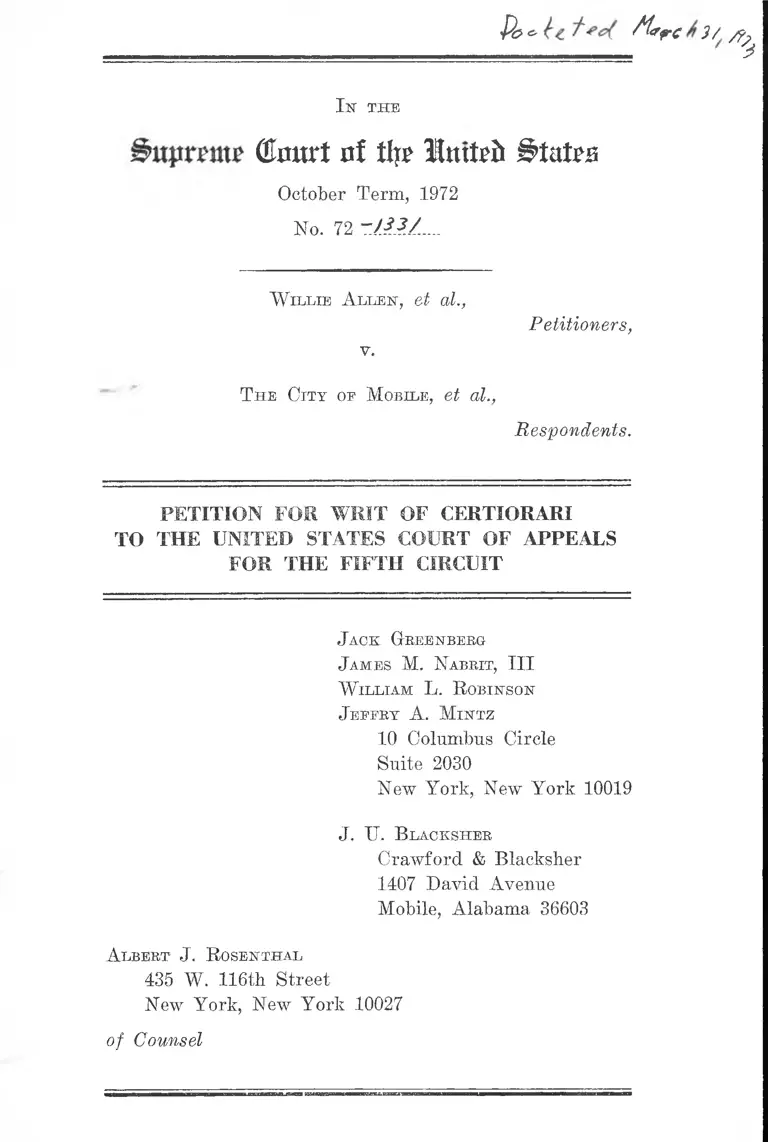

Allen v. City of Mobile Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. City of Mobile Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1973. 9b6e9898-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/90eb374a-c6df-495f-8d34-6f5dfb2a6a2a/allen-v-city-of-mobile-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

P oo MerpC 3 / / f j

-------------------------- 3

I n t h e

G I m t r t n f % I m f r f c S t a t e s

October Term, 1972

No. 72 -J3.1L...

W il l ie A l l e n , el al.,

v.

Petitioners,

T h e C i t t o f M o b il e , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r ii , III

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

J e f f r y A. M in t z

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

J . U . B l a c k s h e r

Crawford & Blacksher

1407 David Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

A l b e r t J . R o s e n t h a l

435 W. 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below ............ ........... ............. ............... ......... 1

Jurisdiction ____ ___________ ______________ __ __ 2

Question Presented.... ............. ............. ......................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved___ 3

Statement of the Case......................................... .... ..... 3

A. Proceedings Below.......... .................................. 3

B. Statement of Facts ............................... ............. 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ .......................... ......... 8

I. The Decision Below Is in Conflict With This

Court’s Decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971) _______ __________ __ ___ 8

II. The Decision Below Is in Conflict With Those of

Other Circuits Which Have Ruled on the Same

or Related Issues .......................... .... ........... ....... 11

III. The Issues Herein Are of Exceptional Impor

tance, Requiring Resolution by This Court ......... 15

C o n c l u s io n ............................................................................................... 16

T a b le o f A u t h o r it ie s

C a s e s :

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Au

thority, 306 F. Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969) ............. 13

Baker v. City of St. Petersburg, 400 F.2d 294 (5th

Cir. 1968) 4

11

PAGE

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of the Bridge

port Civil Service Commission, ----- F. Supp. -----

(D. Conn. Jan. 29, 1973) .... ................................... . 13

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1972) ___ 9,13

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) ....... ...9,12

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir.

1972), 330 F. Supp. 203 (S.D, N.Y. 1971) .......... .......9,11

Fowler v. Schwarzwalder,-----F. Supp.------(D. Minn.

Dec. 6, 1972) ........................ ............... ....... ................. p>

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 .......2, 7, 8, 9,10,11

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., ----- F,2d ----- , 5

E.P.D. 118470 (4th Cir. 1973) ............ ................. .’.... 13

Shield Club v. City of Cleveland, ----- F. Supp. ------

(N.D. Ohio, Dec. 21, 1972) ____________________ 13

United States v. Georgia Power Co., ----- F.2d ----- ,

5 E.P.D. H8460 (5th Cir. 1973) ..... .................................................................’ 14

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5th Cir. 1971) __________ _____________ _____ 14

Western Addition Community Organization v. Alioto,

340 F. Supp. 1351 (N.D. Cal. 1972), 330 F. Supp.

536 (N.D. Cal. 1971) ..................................... ............ 13

S t a t u t e s :

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 86 Stat.

103, March 24, 1972 .............. .......................... ......... 10,15

42 U.S.C. §1983 .........................................................___ 15

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) .............. ..................................... g

O t h e r A u t h o r i t ie s :

pa g e

United States Commission on Civil Rights, For ALL

the People . . . By ALL the People, A Report on

Equal Opportunity in State and Local Government

Employment (1969) .......................... ............... .......... ig

Harrison, Public Employment and Urban Poverty (Ur

ban Institute, 1971) at 1-2 ............... ....................... 15

I n t h e

d m i r t o f t l i r lm fr i&

October Term, 1972

No. 72 ..............

W il l ie A l l e n , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

T h e , C it y o f M o b il e , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in

this proceeding on September 7, 1972.

Opinion Below

The decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit and the order denying the petition for

rehearing, reported at 466 F.2d 122, are printed infra at

la-lOa. The opinion of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama is reported at 371

F. Supp. 1134, and reprinted infra at lla-30a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals was

entered on September 7, 1972. A petition for rehearing

was timely filed and was denied on November 17, 1972. On

February 2, 1973, Mr. Justice Powell signed an order ex

tending the time in which to file the petition for certiorari

to and including March 17, 1973, and on March 7, 1973,

signed an order further extending the time to and including

March 31, 1973. (No. A-807) Jurisdiction of this court is

invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

The defendants administer promotional examinations

which have excluded all but one of the thirty-five black

officers in the Mobile, Alabama Police Department from the

ranks above patrolman. Conceding the tests’ discrimina

tory effect, the defendants and the Courts below have con

cluded that the tests were job related solely on the basis

of the ipse dixerunt of several persons closely connected

with the selection and use of the tests. There was no evi

dence of correlation between performance on the job with

performance on the test. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424, 431 this Court held: “If an employment practice

which operates to exclude Negroes cannot be shown to be

related to job performance, the practice is prohibited.”

Did the Court of Appeals erroneously apply Griggs by

approving this test as a means of selecting officers not

withstanding the test’s racially discriminatory impact and

the lack of any showing of “a demonstrable relationship

to successful performance of the jobs for which it was

used”? Ibid.

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This matter involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States which pro

vides in pertinent p a rt:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of

the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process

of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.

Statement of the Case

A. Proceedings Below

This action was originally filed on March 24, 1969. The

plaintiffs are black members of the Police Department of

the City of Mobile, Alabama, suing on their own behalf and

as a class action, for all present and prospective black

Mobile police officers. Defendants are the City, the mem

bers of the Board of Commissioners of Mobile, the Chief

of Police, and the Members and Executive Director of the

Personnel Board of Mobile County.

As originally formulated, the action challenged various

discriminatory practices of the Police Department, includ

ing the failure to assign black officers to serve in several

divisions of the Department; the exclusive assignment of

black officers to zones with a predominantly Negro popula

tion; the segregation by race of patrol cars; and the use

of discriminatory written and other pre-employment and

promotional tests which were unrelated to the ability of

the candidate to perform the job sought.

4

The District Court issued its order and decree oil Sep

tember 9, 1971. The court sustained the plaintiffs’ allega

tions regarding the assignment of officers and the dis

criminatory effects of the use of seniority and service rat

ings on promotion, and granted substantial relief. De

fendants did not appeal from these aspects of the order.

However, the court found the written promotional ex

amination for sergeant, the one focused on in the evidence,

to he job related, and thus upheld its use despite the sub

stantial racial impact which it had. Plaintiffs appealed

to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit, which affirmed on the basis of the District Court’s

opinion on September 7, 1972, Judge Goldberg dissenting.

Rehearing was denied on November 17, 1972, Judge Gold

berg again noting his dissent.

B. Statem ent of Facts

Prior to 1954, Negroes were totally excluded by law

from employment as police officers in Mobile. (A. 18a,

331 F. Supp. at 1142). Blacks were gradually hired after

that time, and as of the date of the trial in this case, 35

of the 282 sworn officers in the Department, or 12.4%,

were black, in a city where blacks constitute approximately

35% of the population. However a pattern of assigning

officers on the basis of race continued, in violation of the

Fifth Circuit’s decision in Baker v. City of St. Petersburg,

400 F. 2d 294 (5th Cir. 1968) and the district court ordered

the Department to implement a program of assigning offi

cers to patrol beats, patrol cars, divisions of the Depart

ment, and to investigate individual cases on a non-racial

basis as expeditiously as possible (A. 25a-26a; 331 F.

Supp. 1149-1150).

Although the civil service rules governing the Depart

ment make officers eligible to compete for promotions after

5

three years of service, until 1962 no blacks were promoted

above the rank of patrolman, and as of the time of trial,

and indeed the present date, only one has been so promoted

(A. 13a; 331 F. Supp. 1137). As all of the black officers but

the one sergeant (now a lieutenant) were or would shortly

be eligible for promotion to sergeant, and as many of them

took the examination for that position when it was given

in January, 1968, the evidence at trial focused on promo

tion to that rank in general and on the last examination in

particular.1 The undisputed evidence showed that the ex

amination was taken by a total of 108 patrolmen of whom

94 were white and 14 were black. Passing scores were

achieved by 57 of the white officers, or 60.6%, while only

two blacks, 14.3% of those taking it, passed. Neither of

the successful blacks was promoted.2

The test was designed and written by the staff of the

Public Personnel Association (PPA), a cooperative or

ganization of local and state civil service bodies, based

in Chicago, by persons wTho had no direct knowledge of

the job of a police sergeant in Mobile. I t had been used

in Mobile without any attempt whatever to “customize”

it to fit the local situation. In addition to their statistical

1 The examination constitutes sixty percent of the final grade

on the promotional list, and passage of the test is a prerequisite to

consideration for promotion. The District Court found that senior

ity a.nd service rating factors making up another thirty percent of

the final grade were discriminatory, a.nd ordered appropriate revi

sions of them. (A. 18a-19a, 331 F. Supp. at 1142-3.)

2 Examinations scheduled to be given on May 18, 1971, one week

before the trial was to start, were enjoined by the District Court.

Examinations were again scheduled by the defendant Personnel

Board to be held on February 2, 1972. On February 1, the Fifth

Circuit granted appellants’ motion for an injunction barring the

sergeant’s examination pending the determination of the appeal.

An examination for sergeant was held in February, 1973, follow

ing the affirmance by the Court of Appeals. None of the black

officers placed high enough on the resulting eligibility list to be

promoted.

6

evidence, plaintiffs offered expert testimony that the ex

amination was of a nature such that it was likely to he

discriminatory, and that the recognized professional stan

dards of testing psychologists had not been followed by

those who formulated it or in its selection for use in Mo

bile. To substantiate their position that the test would not

adequately predict the job performance of the officers who

took it, plaintiffs also offered evidence regarding black

patrolmen who had demonstrated a high level of per

formance on the job, as indicated by service ratings and

other commendations, but who had scored poorly on the

exam.

To counter this evidence, the defendants offered the testi

mony primarily of two witnesses, the Associate Director of

the Public Personnel Association, the organization which

provided the test, and the Executive Director of the de

fendant Personnel Board which administered it.3 While

both offered the opinion that the test was job related, no

evidence of a correlation between test scores and job per

formance was presented. The PPA representative asserted

that the test had “content validity,” in the sense that the

questions asked accurately related to police work, but

acknowledged that his organization neither had nor could

determine the value of the test in predicting successful

performance of sergeants in any particular locality, and

that they had done nothing to determine whether this

examination had a racially discriminatory impact which

could be eliminated without reducing validity.

The Director of the Personnel Board testified that he had

discussed the test with some police officials, and evaluated

3 The Chief of Police, a lieutenant in the Department’s Planning

Division (A. 17a-18a; 331 P. Supp. at 1141-42) and Sergeant

Richburg, one of the plaintiffs, also gave their opinion that the

test was job-related. None of these men had any experience in test

construction or evaluation.

7

it on. the basis of his own knowledge of the police depart

ment, gained over the years he has been with the Person

nel Board. On that basis alone, he determined it to be

job related in its content. He likewise could, not, however,

produce evidence of any documentation which wmuld demon

strate whether the persons who scored highly on the

examination had in fact performed well on the job, nor

was any effort made to determine whether those who had

been screened out by the examination could perform

equally well or better in the higher rank than those pro

moted. Indeed, no effort was even made to compare the

service ratings regularly given by the Department with

test scores to determine whether those who had been

judged outstanding by their superiors had borne out this

judgment in their test performance, a correlation spe

cifically lacking in the case of several of the black officers.4

On this showing, and in purported reliance on this

Court’s ruling in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, the

trial court found the test to be job-related and thus legally

permissible, despite its effect of almost totally excluding

blacks. Further, on the basis of this finding, which legit

imized the major factor affecting promotion, the District

Court refused to grant the plaintiffs’ request for affirma

tive relief, which sought the appointment of an appro

priate number of qualified blacks to the rank of sergeant,

in order to correct the continuing effects of the alleged

past discrimination. (A. 21a-23a, 331 F. Supp. 1145-1147.)

The plaintiffs appealed from those portions of the Dis

trict Court’s order upholding the promotional tests and

denying affirmative relief. The majority of the Court of

Appeals panel affirmed on the opinion of the District Court.

(A. la ; 466 F.2d at 122)

4 The decree ordered that such records be kept in the future

(A. 27a-28a; 331 F. Supp. 1151-1152).

8

In dissent, Judge G-oldberg stated that the issue was “one

of establishing a standard of review to be applied to a test

when the issue of racial discrimination is adequately and

substantively raised,” (A. 4a, 466 F.2d at 125) and con

cluded “that the district court and the majority applied a

standard of ‘justification’ that required much too little of

the police department” and in so doing, “misconstrued the

thrust of” the decision in Griggs. (A. 5a, 466 F.2d at 126)

He would have held the use of the test unlawful, and

further would have awarded promotions to the Black offi

cers in such manner as to correct the effects of the dis

criminatory practices.

A petition for rehearing with suggestion for rehearing

en banc was filed, urging the points made in the dissent,

and noting the conflict between this decision and other de

cisions of the Fifth Circuit and other circuits in similar

cases. On vote of the full court, rehearing was denied,

Judge Goldberg again dissenting (A. 10a, 466 F.2d 131).

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I .

The Decision Relow is in Conflict With This Court’s

Decision in Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971).

In Griggs, the Court dealt with the legality under the

provisions of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act of the

use of written tests and diploma requirements which had

the effect of excluding substantially greater numbers of

black persons than whites. It held, despite the section of

the statute appearing to approve the use of professionally

developed tests for employee selection (42 IT.S.C. §2000e-

2(h)) that unless the test can “be shown to be related to job

performance [its use] is prohibited.” 401 U.S. at 431. The

9

clear meaning of Griggs, accepted by other circuits which

have considered the question, is that the showing mentioned

must be a substantive one, indicating a “business necessity,”

for the use of the test, and a “demonstrable relationship

to successful performance of the jobs for which it was

used.” Ibid.

Although the present ease was brought under the Equal

Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the courts

below, in concurrence with other courts hearing cases of

public employment discrimination5 held that Griggs gov

erned the issues here. Nonetheless, it upheld this mani

festly discriminatory test on the basis of the most minimal

showing—the unsubstantiated opinions of a few clearly

interested persons that the test was related to the job of

police sergeant. As stated by Judge Goldberg:

I am of the opinion that the district court and the

majority applied a standard of ‘justification’ that re

quired much too little of the police department. The

district court required only that the sergeants’ test be

rationally ‘job related,’ citing Griggs v. Duke Power

Co., supra. Alien v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp. at

1146. I too am of the opinion that the rationale of

Griggs should apply to a discrimination case brought

under section 1983 with force at least equal to its ap

plication to Title YII cases, but I believe that the

district court and the majority have misconstrued the

thrust of that seminal decision and, by analogy, the

constitutional requirements regarding promotional

practices. . . .

Like the district court and the majority, I entertain

no doubt that the sergeants’ test was ‘rationally re

lated’ to the job of being a sergeant. In fact, I would

5 See, e.g. Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725, 732-3 (1st Cir. 1972) ;

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167, 1176-7 (2d Cir.

1972); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 329 (8th Cir. 1972).

10

find it difficult to envision a test that was not somehow

‘rationally related’ to the task of being a police ser

geant. But to stop at this low denominator seems to me

to ignore both any sort of purposive analysis of testing

and the thrust of Griggs. Because the recially dis

criminatory context and effect of the instant test have

been established, I am of the opinion that the state

must demonstrate a substantial interest in maintaining

the use of such a test. (A. 5a, 466 F.2d at 126)

Further, the decision below ignores the Court’s instruc

tion in Griggs that the Guidelines on Employee Selection

issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

are to be followed by the courts in determining the issues

arising under them, as they express “the will of Congress.”

401 XJ.S. at 434. The standard followed by the court below

in upholding the tests can in no way be authorized under

the Guidelines, which require a demonstration of a pro

fessionally acceptable nature by statistics or otherwise to

establish that a selection device is in fact suited for the

purpose for which it is used.

If this decision is permitted to stand, and is followed by

other courts, it will result in a reduction to virtual insig

nificance of the protections against discriminatory employ

ment practices afforded by the Constitution and statutes6

and vitalized by this Court in Griggs. The mere statement

by any person with a patina of expertise, including an agent

of the employer, that a test or other device is in his opinion

“job-related” will serve to legitimate that device, no matter

how discriminatory it has been shown to be in effect or even

intent.

6 By recent amendment, Congress has placed employees of state

and local governments, such as the plaintiffs here, directly under

the protections of Title VII. Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, 86 Stat. 103, March 24, 1972.

11

II.

The Decision Below is in Conflict With Those of

Other Circuits Which Have Ruled on the Same or

Related Issues.

The district court, as affirmed by the majority of the

panel, did agree that the plaintiffs had made a prima facie

showing that the test had a discriminatory impact. Under

such circumstances, in the wake of Griggs, the other cir

cuits, and indeed other panels of the Fifth Circuit, have

required that the use of the device be enjoined in the

absence of a positive demonstrable relationship between

test results and job performance. The conflict between

those decisions and the instant case as to the appropriate

legal standard to be applied is one which this Court must of

necessity resolve.

In Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir.

1972), the court had under consideration an appeal from

the granting of a preliminary injunction barring the use

of all promotional examinations in the New York City

school system on the ground that they were unconstitu

tional. Significantly, on even the most discriminatory of

the several tests at issue, whites passed at only twice the

rate of blacks, id. at.1171, not four times as here. The court

held that “once such prima facie case [of discriminatory

impact] was made, it was appropriate for the district court

to shift to the Board a heavy burden of justifying its con

tested examinations by at least demonstrating that they

were job related.” Id. at 1176 (emphasis added). The court

of appeals approved the district court’s requirement that

such justification be shown empirically, and not simply by

the opinions of those who designed and administered the

tests. See Chance v. Board of Examiners, 330 F. Supp. 203,

216-224 (S.D. N.Y. 1971).

12

In a ease involving the testing of applicants for the posi

tion of police officer, the First Circuit has gone further,

holding that more than a cursory showing of job-related

ness is required.

As to classifications which have been shown to have

a racially discriminatory impact, more is required by

way of justification. The public employer must, we

think, in order to justify the use of a means of selec

tion shown to have a racially disproportionate impact,

demonstrate that the means is in fact substantially re

lated to job performance. It may not, to state the mat

ter another way, rely on any reasonable version of the

facts, but must come forward with convincing facts

establishing a fit between the qualification and the job.

In so concluding, we rely in part on the Supreme

Court’s opinion in Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra.

Faced with a showing of racially discriminatory im

pact without intent, the Court invalidated a require

ment in the alternative which it found to be a barrier

to transfer among the company’s departments, stating

that

‘On the record before us, neither the high school

completion requirement nor the general intelligence

test is shown to bear a demonstrable relationship to

successful performance of the jobs for which it was

used. Both were adopted . . . without meaningful

study of their relationship to job-performance

ability.’ 401 U.S. at 431, 91 S.Ct. at 853.

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725, 732-33 (1st Cir. 1972).

Similarly, the Eighth Circuit en banc approved a district

court’s requirement that written tests for entrance to a

fire department which had a discriminatory impact be re

placed with tests which had been validated in accordance

13

with the guidelines of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission which require empirical validation, Garter v.

Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315, 320, 331 (8th Cir. 1972), the

method sug*gested by Judge Goldberg, A. 9a, 466 F.2d at

130, but rejected by the majority below.7

Quite recently, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, in Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co.,----- F .2d------ ,

5 EPD U8470 (February 20, 1973, No. 72-1267) had under

review a testing battery used for pre-employment evalua

tion by a private employer in a suit brought under Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Although the company

had established a correlation between test scores and some

measures of job performance in several of the positions

for which the tests were used, a substantially greater show

ing than was made by the employer herein, the court held

this to be an insufficient demonstration under Griggs, for

failure to adequately meet the professionally accepted

standards of the EEOC Guidelines.

We agree that some form of job analyses resulting

in specific and objective criteria for supervisory rat

ings is critical to a proper concurrent validation study.

See, Western Addition Community Organization v.

Alioto, 340 F. Supp. 1351,1354-55 (N.D. Cal. 1972). To

require less is to leave the job relatedness requirement

largely to the good faith of the employer and his super

visors. The complaining class is entitled to more under

the Act.

7 Decisions of district courts have been of the same import. See

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, 306

F. Supp. 1355, 1358 (D. Mass. 1969) • Western Addition Com

munity Organization v. Alioto, 340 F. Supp. 1351 (N.D. Cal. 1972)

and 330 F. Supp. 536 (N.D. Cal. 1971) ; Fowler v. Schwarzwalder,

----- F. Supp. ----- (D. Minn. Dec. 6, 1972) ; Shield Club v. City

of Cleveland, ----- F. Supp. ----- (N.D. Ohio, Dec. 21, 1972) ;

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of the Bridgeport Civil

Service Commission, ------ F. Supp. ------ (D. Conn. Jan. 29, 1973),

14

5 E.P.D. H8470 at 7275, slip op. at 9.

The Fifth Circuit itself, in Title VII cases, has de

manded a like standard, greater than that approved here.

In United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418, 456 (1971) the court found insufficient the employer’s

proof that whites wTho scored well on the challenged tests

did wTell on the job.

Griggs demand more substantial proof, most often

positive empirical evidence, of the relationship be

tween test scores and job performance, [citing 401

U.S. at 431] Certainly the safest validation method is

that which conforms with the EEOC Guidelines ‘ex

pressing the will of Congress.’ See id. at 434.

See also United States v. Georgia Power Co., ----- F.2d

----- , 5 E.P.D. H846G (5th Cir. February 14, 1973, Nos.

71-3447 and 71-3293).

Thus it seems evident that the decision below conflicts

with those of other circuits in both public and private

employment cases, and that the Fifth Circuit applies a

different standard to judge the employment practices of

government employers from that applied to private com

panies. The resolution of that conflict and the evaluation

of the appropriateness of that distinction are solely within

the province of this Court.

15

III.

The Issues Herein Are of Exceptional Importance,

Requiring Resolution by This Court.

Federal, state and local governments now employ about

one-fifth, of all wage and salary employees in America,

and the number of jobs in the public sector has grown and

is expected to continue to expand rapidly.8 Last year, Con

gress amended the equal rights laws to place government

employees under the protections of Title VII. Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Act of 1972, 80 Stat. 103, March 24,

1972. Additionally, the Equal Protection Clause, as en

forced through 42 TJ.S.C. § 1983, remains as an independent

right and remedy for persons who are denied equal oppor

tunity in public employment. A recent federal study has

shown that those of minority races or ethnic groups are

often grossly underrepresented in such employment.9 Be

cause of the prevalence of civil service “merit” systems,

the use of pre-employment and promotional tests is even

more widespread in government than in private industry.

Thus the determination of what standards govern the

validation of tests, and whether those standards should be

different in the two spheres, is of major importance.10

Moreover, as the citations above suggest, there are a large

number of cases dealing with the validation of employment

8 Harrison, Public Employment and Urban Poverty (Urban In

stitute, 1971) at 1-2; see, United States Commission on Civil

Rights, For ALL the People . . . By ALL the People, A Report on

Equal Opportunity in State and Local Government Employment

(1969).

9 United States Commission on Civil Rights, op. cit. supra n. 8.

10 We submit further that an incidental but important benefit of

requiring civil service systems to use only tests which in fact

measure potential job performance will be an improvement in the

general caliber of the public service.

16

tests which, in the wake of the Civil Eights Act of 1964

and the Griggs decision, has become a major area of litiga

tion in the lower federal courts. It is of great importance

that this Court provide guidance and clarification of the

legal standards to be applied, and that it reconcile the

conflicts in the lower courts.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

J a m e s M. N a b r it , III

W il l ia m L. R o b in s o n

J e f f r y A. M in t z

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

J . U . B l a c k s h e r

Crawford & Blacksher

1407 David Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

A l b e r t J . R o s e n t h a l

435 W. 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

of Counsel

APPENDIX

Appendix A

(O pin ions of the C ourt of Appeals)

Willie ALLEN et al., Plainttffs-

Appellante,

v.

The CITY OF MOBILE et aL, Defendants-

Appellees.

No. 72-1009.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Sept 7, 1972.

Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc

Denied Nov. 17, 1972.

A. J. Cooper, Jr., Mobile, Ala., Jack

Greenberg, Jeffry Mintz, William L.

Robinson, New York City, for plain-

tiffs-appellants.

Mylan R. Engel, Fred G. Collins, Mo

bile, Ala., for defendants-appellees.

Before BELL, GOLDBERG and RO

NEY, Circuit Judges.

PER CURIAM:

Plaintiffs, black officers of the Mobile

Police Department, sued the defendants

claiming that various practices of the

Police Department discriminated against

Negro officers on account of their race.

[1] We agree with the plaintiffs’

statement contained in their brief that

the district court, in granting substan

tially all relief sought on the subject of

racial assignment of officers, in order

ing changes to reduce or eliminate the

discriminatory impact of seniority and

service ratings, and in requiring that in

struction in intergroup relations be giv

en to all officers and that the defend

ants undertake affirmative efforts to re

cruit black officers, has made possible

substantial progress toward the achieve

ment of the elimination of unlawful ra

cial discrimination and the elimination

of the vestiges of past discrimination.

[2] Plaintiffs’ sole issue on this ap

peal, however, is that the district court,

in fashioning a remedy, did not enjoin

the use of a written test, which they

contend is discriminatory as to blacks,

given to promote officers to the rank of

sergeant. The district court found that

the test is job-related. We affirm the

judgment of Chief Judge Pittman on the

basis of his order and decree reported

at 331 F.Supp. 1134 (S.D.Ala.1971).

Affirmed.

GOLDBERG, Circuit Judge (dissent

ing) :

It is with great reluctance that I dis

sent in this case, for I am conscious of

the synoptic analysis of the problems

surrounding testing procedures and of

the enlightened decree entered by the

distinguished trial judge. Allen v. City

of Mobile, S.D.Ala.1971, 331 F.Supp.

la

2a

Appendix A

1134. Despite the innovations and cour

age implicit in the trial judge’s reforma

tion of the hiring practices of the police

force of Mobile, however, I am convinced

that he stopped just short of this case’s

Rubicon by failing to wade into the

deeper waters and to seine for a more

optimal test for police promotions. In

addition, I am compelled to conclude

from the findings of fact of the able

district judge that the traditional re

quirements of equity mandate more im

mediate relief than that afforded in the

decree affirmed by the majority.

The area of occupational and promo

tional testing is both new and confusing

to the courts. So-called “objective” tests

were once hailed as the definitive an

swer to “subjective,” often discrimina

tory, hiring or promotion procedures.

But it has become increasingly clear as

analysis becomes more sophisticated that

there can be other, much more subtle,

forms of discrimination lurking in

“objective” testing. It is now recog

nized that a test can be impeccably

"objective” in the manner in which the

questions are asked, the test adminis

tered, and the answers graded, and still

be grossly “subjective” in the education

al or social milieu in which the test is

set. See generally U. S. Comm, on Civil

Rights, For ALL the People . . . By

ALL the People (1969); Comment, “Le

gal Implications of the Use of Standard

ized Ability Tests in Employment and

Education,” 68 Colum.L.Rev. 691 (1968).

I am persuaded that neither the able

district judge nor the majority of this

panel has applied an appropriate stand

ard of review when a court is confronted

with the admittedly difficult problem of

reviewing tests. I do not know that I

can provide here a more appropriate

standard, but I can suggest some guide

lines in the context of this case that

seem to me to confront the deeper issues

regarding testing.

A test alone is not talismanic; it

should, in my opinion, be placed in its

own context of valid predicative force

for the appropriate position of skill and,

in some circumstances, of its discrimina

tory effect. This Court has already con

cluded that promotional tests, as well as

hiring tests, are subject to judicial scru

tiny. See United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 5 Cir. 1971, 451 F.2d 418.

It is beyond question at this point in the

nation’s history that discriminatory

state employment practices are constitu

tionally invalid, save for those rare cases

in which the state can show a substantial

interest in maintaining a practice shown

to be discriminatory. Appellants have,

to paraphrase Mr. Justice Holmes’ now

diluted dictum, no constitutional right to

be policemen. But they do have a consti

tutional right to “be free from unreason

able discriminatory practices with re

spect to such employment.” Whitner v.

Davis, 9 Cir. 1969, 410 F.2d 24, 30. See

also Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 1971, 401

U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d 158;

Castro v. Beecher, 1 Cir. 1972, 459 F.2d

725; Chance v. Board of Examiners, 2

Cir. 1972, 458 F.2d 1167; Carter v. Gal

lagher, 8 Cir. 1971, 452 F.2d 315; Rolfe

v. County Board of Education of Lincoln

County, Tennessee, 6 Cir. 1968, 391 F.2d

77; Wall v. Stanly County Board of Ed

ucation, 4 Cir. 1967, 378 F.2d 275; cf.

Wieman v. Updegraff, 1952, 344 U.S.

183, 73 S.Ct. 215, 97 L.Ed. 216; Nor

walk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, 2 Cir. 1968, 395 F.2d 920. And

of course even though police work is un

questionably sensitive, that sensitivity

cannot ipso facto justify an unconstitu

tional procedure. See Washington v.

Lee, M.D.Ala.1966, 263 F.Supp. 327

(three-judge court); aff’d per curiam,

1968, 390 U.S. 333, 88 S.Ct. 994, 19 L.

Ed.2d 1212; Morrow v. Crisler, S.D.

Miss.1971, No. 4716 [Feb. 12, 1971, Oct.

4, 1971], appeal pending, No. 72-1139

(written test for highway patrol en

joined as unvalidated); Baker v. City of

St. Petersburg, 5 Cir. 1968, 400 F.2d

294; Castro v. Beecher, supra.

The patrolman in the instant case

demonstrated beyond question that the

Mobile police department was rife with

discriminatory procedures, discrimina

tion that the trial judge specifically

8a

Appendix A

found and that the majority accepts.1

Since the Mobile police department was

wrenched from its “whites only” status

in 1954, only one black patrolman has

been promoted to sergeant (in 1962) in

a force in which 12.4% of the officers

are black and in a city approximately

one-third black. It appears from the rec

ord that this one sergeant was placed in

positions within the department that pre

cluded him from ever supervising any

white officers. In addition, the one

black sergeant twice took and passed the

test for lieutenant, but had not been

promoted at the time of the trial.

It is in the context of these findings

that this Court must, in my opinion,

view the testing issue.2 The record

demonstrates that a significantly larger

percentage of black applicants failed the

test than did white applicants. Of 94

white applicants, over 60% passed; of

14 black applicants, about 14% passed.

It is acknowledged by all parties that

the test has a critical impact upon pro

motion and that failure to achieve a

passing grade of TO precludes promotion

altogether. Statistics, of course, are

usually not conclusive of a proposition of

fact, but “ [i]n the problem of racial dis

crimination, statistics tell much, and

Courts listen.” State of Alabama v.

United States, 5 Cir. 1962, 304 F.2d 583,

aff’d per curiam, 371 U.S. 37, 83 S.Ct.

145, 9 L.Ed.2d 112; see also Turner v.

Fouche, 1970, 396 U.S. 346, 90 S.Ct. 532,

24 L.Ed.2d 567; Hawkins v. Town of

Shaw, 5 Cir. 1971, 437 F.2d 1286, modi

fied en banc, 5 Cir. 1972, 461 F,2d 1171

[1972]. Although it is not noted in

t . As a particularly sad example, the trial

judge found it necessary from the evidence

presented to him to enjoin the use of the

epithet “nigger” in the police force; in

addition, he found that there was assign

ment of police beats by race in open de

fiance of this Court’s decision in Baker

v. St. Petersburg, supra, and various

other overtly racial acts by the police

department, all of which are delineated in

the district court’s opinion. We acknowl

edge also the district court’s observation

that a new administration appears to have

decreased somewhat the more blatant dis

crimination in the department.

2. The test in question is described by the

district court. Allen v. City of Mobile,

the district court's opinion, the record

also shows that the police department’s

promotion sheets record the race of the

applicant alongside the test scores.3

The district court and this panel are in

agreement that the appellants produced

during the trial a prima facie case that

there was clear racial discrimination in

the Mobile police department.

The other circuits have found racial

discrimination in testing situations

where there is not the history and exist

ing milieu of racial discrimination that

there is in the instant case. These cir

cuits place more emphasis upon the bare

statistics regarding substantial racial

difference in rates of passing and pro

motion than I would find necessary in

this case. See Castro v. Beecher, supra;

Chance v. Board of Examiners, supra;

Carter v. Gallagher, supra. Given the

pronounced racial effect in the ser

geants’ test, accompanied by the findings

of the district court that the majority

now upholds regarding the long and deep

history of racial practices in the police

department, I would conclude that appel

lants have made a prima facie case that

the sergeants’ test is a part of the de

partment’s unconstitutional action. And

if a prima facie constitutional violation

is demonstrated, it is unnecessary, as a

general proposition, that the plaintiff

also establish a discriminatory intent on

the part of the offending persons. See

Whirl v. Kern, 5 Cir. 1969, 407 F.2d 781,

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 901, 90 S.Ct. 210,

24 L.Ed.2d 177; Hawkins v. Town of

Shaw, supra; Daniels v. Van de Venter,

10 Cir. 1967, 382 F.2d 29; Pierson v.

331 F.Supp. at 1141. I t is prepared by

the National Publie Personnel Association

of Chicago, a cooperative organization of

local and state civil service officers.

However, 1 have examined the record,

and I must conclude that the district

judge was incorrect when he stated that

Dean O. W. Wilson of the University of

California, a renowned expert in tile field,

aided in the preparation of the test in

question. The record demonstrates only

that Dean Wilson’s materials were read

by those preparing the test.

3. The last scores available for use at trial

were those recorded in 1968.

125

4a

Appendix A

Ray, 5 Cir. 1965, 352 F.2d 213, rev’d on

other grounds, 386 U.S. 547, 87 S.Ct.

1213, 18 L.Ed.2d 288; cf. Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 1961,

365 U.S. 715, 81 S.Ct. 856, 6 L.Ed.2d 45.

I would also argue, however, that the

record and the district court’s opinion

and decree evince some conviction that

the police department’s procedures were,

at least in part, discriminatory by in

tent. See, e. g., Allen v. City of Mobile,

331 F.Supp. at 1138. I do not, however,

base my dissent upon a specific finding

of so-called “intentional” discrimination

by the department.4

4. I realize that the "compelling state in-

terest” test in all of its ramifications has

not yet been applied to situations involv

ing so-called “unintentional” discrimina

tion, and I do not analytically approach

this dissent with the idea that this is a

so-called “intent” case. Nevertheless, I

do not fully agree with distinctions often

drawn in similar cases between “inten

tional” and “unintentional” racial dis

crimination. See, e. g., Chance v. Board

of Examiners, supra; Castro v. Beecher,

supra. I t appears to me that “motive”

is often simply another way of stating

that the statistical evidence and the con

text in which the statistics are set are

sufficient to allow, if not compel, a prima

facie inference of “intent.” See Swain

v. Alabama, 1965, 380 U.S. 202, 85 S.Ct.

824, 13 L.Ed.2d 759. Similarly, one who

employs a test that unerringly produces

greatly divergent results among appli

cants of different races and who makes

no attempt whatsoever to study or to

justify the reasons for that divergence

can reasonably be said to employ a dis

criminatory tost with “intent.” His “in

tent” need not necessarily be the less for

purposes of enforcing the Constitution

simply because he continues to use a de

vice with known discriminatory effect

rather than choosing to announce openly

his discriminatory employment devices or

to couch such devices in methods less sub

tle than testing:

“ [W ]e now firmly recognize that the

arbitrary quality of thoughtlessness can

be as disastrous and unfair to private

rights and the public interest as the

perversity of a willful scheme.”

Hobson v. Hansen, D.D.C. 1967, 269 F.

Supp. 401, 497.

The degree of “justification” by the state

to maintain a process or device discrimi

natory in fact cannot turn simply upon

the fact that one practice might have

been transcribed into statute and another

The real issue of this case with re

gard to testing becomes one of establish

ing a standard of review to be applied to

a test when the issue of racial discrimi

nation is adequately and substantively

raised. I am guided in my analysis by

cases decided under Title VII of the Civ

il Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. §

2000a et seq., although Title VII is not

specifically applicable to a local police

department, 42 U.S.C.A. § 2000e. It ap

pears to me, however, that the rationale

of Title VII, as elucidated in Griggs v.

Duke Power, supra, provides a strong

analogy to similar issues that are raised

practice followed unerringly in fact. See

Johnson v. State of Virginia, 1963, 373

U.S. 61, 83 S.Ct. 1053, 10 L.Ed.2d 185;

Lombard v. State of Louisiana, 1963, 373

U.S. 267, 83 S.Ct. 1122, 10 L.Ed.2d 338;

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent

School Dist., 5 Cir. 1972, 459 F.2d 13

[1972] (en banc) ; United States v.

Texas Education Agency, 5 Cir. 1972,

467 F.2d 848 [1972] (en banc); cf.

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Soci

ety, 4 Cir. 1965, 355 F.2d 718; Cypress

v. Newport News Gen. and Nonsectarian

Hosp. Ass’n, 4 Cir. 1967, 375 F.2d 648.

Enforcement of the Fourteenth Amend

ment’s prohibitions against racial dis

crimination is not a matter of “punish

ing” those “guilty” of discrimination, and

accordingly the degree of justification re

quired in discrimination cases should not

turn upon the relative degree of “offen

siveness” among perpetrators of racially

discriminatory acts. I f the prohibition

of racially discriminatory acts is far

from “punishment” but is rather

the enforcement of constitutional rights

and responsibilities under the Fourteenth

Amendment, then perhaps “intent” should

mean nothing more than the knowing per

petration of a racially discriminatory act

or practice. To attempt to differentiate

the burden of proof that is required to

justify a discriminatory act upon the

existence or degree of bad motive on the

part of the perpetrator of the act seems

to me to focus upon an unworkable issue

and to ignore the entire thrust and pur

pose of the Fourteenth Amendment.

However, I note again that the lack of a

specific finding of so-called “intent”

either by the trial judge or by this panel

does not reflect in any way the substance

of my dissent. I have approached the de

partment’s action as “unintentional,” in

the previously discussed meaning of that

term.

5a

Appendix A

under the aegis of the Constitution and

42 U.S.C.A. § 1983 with regard to ac

tions by state or local employees. Ac

cord, Allen v. City of Mobile, supra;

Chance v. Board of Examiners, supra;

Carter v. Gallagher, supra; Castro v.

Beecher, supra. I cannot conclude that

constitutional rights litigable under sec

tion 1983 would be entitled to signifi

cantly less thorough examination than

rights founded upon congressional stat

ute. In addition, I note that the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

has amended Title VII to include, among

others, precisely the employees in ques

tion in the instant case.

The district judge should first exam

ine the passing spread of the test, as the

able district judge in this case did. If

there is a substantial difference between

black and white applicants in the rates

of passing in the context of other evi

dence of racial discrimination, then the

offending person or persons should be

required to establish reasons for utiliz

ing the tests. Put another way, when a

prima facie case for unconstitutional ac

tion on the basis of race has been made,

the burden should be upon the police de

partment to justify its reasons for con

tinuing actions that have been adequate

ly called into constitutional question.

See, e. g., Chance v. Board of Examin

ers, supra; Castro v. Beecher, supra;

Carter v. Gallagher, supra. A peculiar

result would ensue if a private defend

ant in a case alleging racial discrimina

tion in employment or promotional prac

tices were required to assume the bur

den of demonstrating the validity of sus

pect practices, and a public defendant al

legedly engaging in precisely the same

practices were not. See Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. §

2000a et seq., and amendments to Title

VII by the Equal Employment Opportu

nity Act of 1972. In addition, it is the

police department that, presumably,

readily has the necessary information to

justify its own procedures.

It is at this point in the review of a

test that my divergence with the majori

ty is greatest. I am of the opinion that

the district court and the majority ap

plied a standard of “justification” that

required much too little of the police de

partment. The district court required

only that the sergeants’ test be rational

ly “job related,” citing Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., supra. Allen v. City of Mo

bile, 331 F.Supp. at 1146. I too am of

the opinion that the rationale of Griggs

should apply to a discrimination case

brought under section 1983 with force

at least equal to its application to Title

VII cases, but I believe that the district

court and the majority have miscon

strued the thrust of that seminal deci

sion and, by analogy, the constitutional

requirements regarding promotional

practices. If “ . , . the jobs in

question formerly had been filled only by

white employees as part of a long-stand

ing practice of giving preference to

whites . . . ” and the test operates

“ • • • to disqualify Negroes at a

substantially higher rate than white ap

plicants,” Griggs v. Duke Power, 401

U.S. at 426, 91 S.Ct. at 850, 28 L.

Ed.2d at 161, then the police depart

ment should have to prove that the

test bears “ . . . a manifest rela

tionship . . . ” to the position of

police sergeant. Griggs v. Duke Power,

401 U.S. at 432, 91 S.Ct. at 849, 28 L.Ed.

2d at 165 [emphasis added].

Like the district court and the majori

ty, I entertain no doubt that the ser

geants’ test was “rationally related” to

the job of being a sergeant. In fact, I

would find it difficult to envision a test

that was not somehow “rationally relat

ed” to the task of being a police ser

geant. But to stop at this low denomina

tor seems to me to ignore both any sort

of purposive analysis of testing and the

thrust of Griggs. Because the racially

discriminatory context and effect of the

instant test have been established, I am

of the opinion that the state must dem

onstrate a substantial interest in main

taining the use of such a test. The

First and Second Circuits have recently

adopted standards very similar to those

I propose here. See Castro v. Beecher,

supra, (also a police department case);

Chance v. Board of Examiners, supra

(supervisory positions in a school sys

tem) ; see also Carter v. Gallagher, su

pra, (firemen). While the standard I

6a

Appendix A

propose approaches the “compelling state

interest” test often appropriate in cases

of racial discrimination, compare Mc

Gowan v. Maryland, 1960, 366 U.S. 420,

81 S.Ct. 1101, 6 L.Ed.2d 393, with Lov

ing v. Virginia, 1967, 388 U.S, 1, 87 S.

Ct. 1817, 18 L.Ed.2d 1010 (intentional

discrimination ease), in terms of the de

gree of proof required to justify con

tinuing the discriminatory impact of a

test, I am in agreement with the First

Circuit that the test is inappropriate

"[t]o the extent . . . that

[“compelling state interest”] connote[s]

a lack of alternative means” under the

facts of this case. Castro v. Beecher,

459 F.2d at 733; see also Carter v. Gal

lagher, supra; Chance v. Board of Ex

aminers, supra; Penn v. Stumpf, N.D.

Cal.1970, 308 F.Supp. 1238; supra note

4. The police department should not be

required to select an “optimal” test so as

to erect some form of racial balance in

its sergeants’ staff. See 42 U.S.C.A. §

2000e-2(j). However, the department

should be required to make a substantial

showing of job-relatedness, which it was

clearly not required to do by the district

judge or by the majority.

It appears that there are a number of

methods available by which to evaluate

substantial job-relatedness, see general

ly, Cooper & Sobol, “Seniority and Test

ing Under Fair Employment Laws: A

General Approach to Objective Criteria

of Hiring and Promotion,” 82 Harv.L.

Rev. 1598 (1969); Chance v. Board of

Examiners, supra, but there appear to

be two major methods:

“One is ‘content validation,’ which re

quires the examiners to demonstrate

that they have formulated examina

tion questions and procedures based

on an analysis of the job’s require

ments, usually determined through

empirical studies conducted by ex

perts. . The other method

of evaluating job-relatedness is ‘pre

dictive validation,’ which requires a

showing that there is a correlation be-

5. The state also presented the testimony

of the executive director of the personnel

board that administered the test, but it

appears from the record that the execu

tive director was not conversant with

tween a candidate’s performance on

the test and his actual performance on

the job.”

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d

at 1174. It appears that the district

court attempted to utilize a “content va

lidity” examination, for the opinion

looks only to the questions themselves.

The court below was faced with con

trasting expert testimony, as is becom

ing usual in cases requiring any sort of

expert opinion. Neither expert witness

had any actual knowledge of the Mobile

police department itself.5 The state’s

expert witness, however, was also the

originator of the test. Allen v. City of

Mobile, 331 F.Supp. at 1141. Under

cross-examination he testified that no

studies whatsoever had been made by

his firm with regard to the possible ra

cially discriminatory effect of the ser

geants’ test. In the context of demon

strated racial prejudice in other facets

of the department’s procedures and a

prima facie case that the test itself is

racially discriminatory, I would require

that the authority offering the test at

least conduct studies regarding racial

impact before that authority could con

vincingly insist that the test has “con

tent validity.” In addition, it appears

that the test was based entirely upon a

so-called "job description” prepared in

1959 by an outside consulting agency

that was not called to testify at the trial

below. I fail to understand how a test

that is based upon a “description” of

thirteen years ago, which description the

testing agency itself neither prepared

nor updated, can have “content validity”

sufficient to pass muster under the facts

of this case in the absence of much more

substantial “content” analysis than ap

pears in the transcript. Moreover, ap

pellants dispute whether the “job de

scription” itself was adequate, even in

dependent of the fact that it was made

quite some time ago. There is no find

ing with regard to the adequacy of that

description upon which the questioned

testing analysis and had himself made no

personnel studies or analysis regarding

the predictive or content validity of the

test in question.

7a

Appendix A

test was based, nor does it appear that

any examination of the “job description”

ever took place at the trial below. Fi

nally, the testing agency that prepared

the tests has not itself made any studies

regarding the comparative performance

of officers with high and low test scores

so as to examine the efficacy of their

own test. In sum, I contend that the

analysis of “content” in the instant case

was completely superficial and wholly

insufficient as a matter of law to consti

tute “content validity.”

I do not intimate in any way that val

idation must be particularized to the lo

cal community by an expert organiza

tion. Such a requirement would be a

great financial and time burden, impos

sible to fulfill in some smaller communi

ties. But see NAACP v. Allen, M.D.

Ala.1972, 340 F.Supp. 703 [1972], where

6. I should note in passing a few of the

questions in the test.

“31. The most important rule to re

member when questioning children

and low-intelligence adults is to

(1) speak clearly.

(2) treat them as any other sus

pect.

(3) allow such suspects wide free

dom of narration.

(4) avoid suggestions.

“32. The success of a patient, well-

planned interrogation of a pre

sumed guilty party pleading inno

cent is based on the assumption

that it is

(1) impossible to commit the per

fect crime.

(2) possible to detect the veracity

of the suspect by observing him.

(3) difficult to lie consecutively

and logically.

(4) impossible for the suspect to

live with his guilt very long.

“33. Boys aged 10 to 15 can provide

reliable testimony and are espe

cially keen observers in areas re

lating to

(1) phenomena of nature.

(2) intimate occurrences.

(3) girls of the same age.

(4) moral matters.

“39. As a general rule, the first ap

proach to questioning a suspect

should be

(1) emotionally confusing.

(2) direct and friendly.

(3) Stern and authoritarian.

(4) indifferent.

the district judge himself “localized” a

challenged test to some extent by remov

ing some questions and altering others.

I do urge, however, that, in addition to

those factors that I have just outlined,

any so-called “content validation” should

be demonstrated by some organization

other than that which drew up the test.

Without disparaging the expertise or the

opinions of test originators in any way

whatsoever, the originators do have an

interest in maintaining the public integ

rity of their own inventions. After all,

if a reputable organization proffers a

test, it is obviously convinced in its

own mind that the test is sufficiently

valid as to content. That opinion,

however well-intentioned, should not pro

vide the sole evidence of validity to a

court, for the question presented is sim

ply too important and subtle for such an

examination.6 See Castro v. Beecher,

“40. To inspire full confidence on the

part of his subject it is vital that

the interrogator establish that his

attitude is one of

(1) dignity and objectivity.

(2) belligerence and intimidation.

(3) efficiency and aloofness.

(4) sympathy and understanding.

“46. Experience has shown that several

types of motives predominate in

arson cases. That one of the fol

lowing occurs more frequently

than all of the others is

(1) revenge.

(2) pyromania.

(3) economic gain.

(4) intimidation.

“67. In deciding whether a case in

volving a juvenile delinquent

should be referred to a casework

agency or to juvenile court, which

of the following factors would

likely be the last to be considered?

(1) the parents’ desire for help.

(2) the juvenile’s school record.

(3) the emotional needs of the

juvenile.

(4) the number of offenses com

mitted by the juvenile.

“73. The use of narcotic drugs by

juveniles seems to progress ac

cording to three definite steps.

Generally, the first step ultimately

to addiction is the use of

(1) alcohol.

(2) marijuana.

(3) opium.

(4) codeine.

8a

Appendix A

supra-, Chance v. Board of Education,

supra.

Moreover, in the context of a showing

of substantial racial bias in the police

department and in the absence of suffi

cient “content validation” to explain ob

vious racial effect, I am of the opinion

that any test used to exclude patrolmen

from becoming sergeants must be vali

dated by a comparison of performances

under a “predictive validation” scheme.

The testimony of police officials in the

transcript reveals clearly that the de

partment is seeking a predictive effect

when it administers tests and other pro

cedures for promotion. The department

does not seek only or even primarily to

reward past performance or seniority.

The district judge, in fact, agreed with

this general approach to testing. With

regard to written tests the district

court’s decree ordered that

“ [n]ot less than once each year here

after from the date of this decree the

defendants are to submit a written re

port to the court which consists of a

statistical study of promoted officers

which will show a comparison between

their examination grade and their

regular service or performance rat

ings.”

Thus the district court concluded that

there should be some empirical relation-

Note 6—Continued

“74. The largest number of juvenile

delinquents appearing before the

juvenile court fall into which one

of the following age groups?

(1) 12-14 year age group.

(2) 16-18 year age group.

(3) 14-16 year age group.

(4) 18-20 year age group.

“76. Authorities in the field of crimi

nal behavior know that nearly all

confirmed adult criminals

(1) are sooner or later appre

hended and punished for their

crimes.

(2) start their careers as juvenile

offenders.

(3) are substandard in intelli

gence.

(4) develop as a result of no

religious training.

“77. The more effective the police are

in reducing the frequency of con-

ship between test scores and perform

ance actually demonstrated, and the ma

jority agrees with that conclusion.

While I disagree with the district judge

and the majority with regard to the

quantum of “relationship” that should

be required under the facts of this case,

I am in agreement with the thrust of

this approach. However, once again I

am convinced that the district court and

the majority have overlooked the nature

of a cut-off test. The decree entered

below and affirmed here acknowledges

that there may be substantial inverse

differences in performance between, for

example, a sergeant promoted with a

test score of 71 and a sergeant promoted

with a test score of 90. By the same

reasoning, I am compelled to conclude

on the basis of this record that there

might also be substantial inverse dif

ferences in performance between appli

cants who had test scores of 69 and

71, or for that matter between appli

cants with test scores of 50 and 90.

Without some such empirical study of

racial effect and/or performance, I am

wholly unable to conclude that the test is

“valid” under any validation theory and

under the Fourteenth Amendment and

the rationale of Griggs v. Duke Power,

supra. See United States v. Jacksonville

Terminal Co., 5 Cir. 1971, 451 F.2d

418, cert, denied, 406 U.S. 906, 92 S.

tact, the more effective they are in

reducing exposure to venereal

disease. Therefore, health author

ities are in agreement that the

most effective way to combat the

spread of venereal disease is

(1) to suppress prostitution.

(2) to legalize prostitution.

(3) to require regular medical in

spection of all prostitutes.

(4) to encourage and sponsor sex

education classes in the secondary

schools.”

These are just a few of the questions, of

course. But one could argue convincing

ly, I believe, that the above questions are

(1) only very tangentially relevant.

(2) subject to considerable disagreement

among experts.

(3) calling for very subjective judgments

among close alternatives.

(4) based on very specific knowledge not

generally available or read.

(5) all or any combination of the above.

9a

Appendix A

Ct. 1607, 31 L.Ed.2d 815 [1972], There

is a set of guidelines already iij exist

ence prepared by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission. See 29 C.F.R.

§§ 1607.1-1607.9. In addition, that

same organization apparently evaluates

large numbers of specific employment

and promotion tests. This Court con

cluded in another employment context

that “ . . . the safest validation

method is that which conforms with the

EEOC Guidelines.” United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d at

456; see also Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. at 433, 91 S.Ct. 849, 28 L.Ed.2d

at 165.

In addition to my great doubts re

garding the legal standard applied by

the district court and the majority to

determine a lack of unconstitutional dis

crimination in the test in question, I am

also convinced that the district judge

should have employed immediately effec

tive injunctive relief. It is reasonably

well settled at this point that so called

“affirmative" hiring measures are some

times required to offset the effects of

past discrimination. See, e. g., United

States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., su

pra; Carter v. Gallagher, supra; United

States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 9 Cir.

1971, 443 F.2d 544, cert, denied, 404 U.

7. The state argues that United States v.

Jacksonville Terminal, supra, is inappo

site to the instant case because the Jack

sonville Terminal case involved an apti

tude test for unskilled workers, while

the instant case deals with admittedly

very skilled work. I agree that police

work is, of course, substantially more

sensitive and skilled than unskilled bag

gage carrying, but I do not agree that this

factor decreases the force of the excellent

opinion in Jacksonville Terminal regard

ing immediate relief. The “labor pool”

from which the Mobile police department

draws for its sergeants consists of its own

patrolmen, whose qualifications as police

officers have never been questioned during

the course of this case. I agree that the

rationale of Jacksonville Terminal might

be inapposite to the instant case if the

potential “labor pool” from which police

sergeants were to be promoted for pur

poses of immediate relief were only the

general pool of available labor. However,

the pool consists of men already very

skilled in the task of being police officers,

S. 984, 92 S.Ct. 447, 30 L.Ed.2d 367;

Local 53 of Int. Ass’n of Heat and Frost

Insulators and Asbestos Workers v. Vog-

ler, 5 Cir. 1969, 407 F.2d 1047; United

States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., W.

D.N.C.1970, 325 F.Supp. 478; Contrac

tors Ass’n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of

Labor, 3 Cir. 1971, 442 F.2d 159, cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 854, 92 S.Ct. 98, 30 L.

Ed.2d 95.7 There are a number of ways

to accomplish immediate relief. See, e.

g., Cooper & Sobol, 82 Harv.L.Rev. at

1132. I would leave the precise formula

tion of any methodology of promoting a

reasonably flexible number of black pa

trolmen to the rank of sergeant to the

district judge, who has demonstrated

clearly both his ability and his objectivi

ty in his determinations of this case, de

spite my disagreements on these two

points of law.8 I would propose, how

ever, that the immediate promotions

that would take place during the interim

period (prior to the time that a validat

ed test and other corrective procedures

ordered by the district judge could be

established) should be made roughly in

approximation to the percentage of black

patrolmen on the force. I emphasize,

however, that this would be only interim

hiring and that my proposed rough per

centages for promotion should be flexi-

presumably very much the same skills

required of a police sergeant. The ration

ale of Jacksonville Terminal is correct for

the potential baggage-carriers of that case

and for the potential police sergeants of

this case.

8. For example, the department could be

required to promote one black patrolman

for every eight white patrolmen promoted

(approximately the ratio of black to white

patrolmen). See, e. g., NAACP v. Allen,

supra; Carter v. Gallagher, supra ;

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

supra; Contractors Ass’n of Eastern Pa.

v'. Secretary of Labor, supra. Or the dis

trict court could adjust any test employed

by the department so as to equalize more

appropriately the racial effect of the test.

See Cooper & Sobol. 82 Harv.L.Rev. su

pra. Such an adjustment would not

amount to unequal treatment to the white

applicants ; rather, it would be a recog

nition of the effects of unsubstantiated

racial or cultural orientation, and a cor

rective.

10a

Appendix A

ble to meet the circumstances and would

be utilized only for purposes of interim

reference. See Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 1971,

402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d

554. My conclusion that more immedi

ate equitable relief is compelled in the

instant case is based upon the district

court’s own findings regarding the Mo

bile police department, which has been

generally immobile in matters of dis

crimination. Simply stated, no black

man has ever been allowed to be placed

in a supervisory position over white pa

trolmen, even the one black patrolman

who managed to pass the sergeants’ test.

I would propose, finally, that this in

terim promotion scheme also be em

ployed to test empirically the predictive

validity of the test in question. . The

performance of officers promoted par

tially by means of the test could be com

pared with the performance of officers

promoted on other factors and without

reference to the questioned test. Noth

ing I have stated in dissent should be

construed to forbid the department’s em

ployment of another test, one more ap

propriately and thoroughly validated as

to predictive force and to content (in

cluding racial/cultural analysis). And,

of course, any performance testing by

the department is subject to review by

the district court.

An attempt is now under way to

equalize substantially educational oppor

tunities for all the nation’s children. If

and until that effort reaches some rea

sonable degree of fruition, the Constitu

tion cannot stand immobile while a gen

eration of working police officers suf

fers from the continuing operations and

effects of racially discriminatory proce

dures, however subtle. While the major

ity would require no immediate pruning

of the foliated discrimination, and while

I would not require immediate scything

of every “root and branch,” I would

commit to the judicious husbandry of

the able trial judge some immediate de

foliation of the poisonous trees of dis

crimination so deeply rooted in the Mo

bile police department. I would reverse

and remand to the district court on the

two points of law that I have raised.