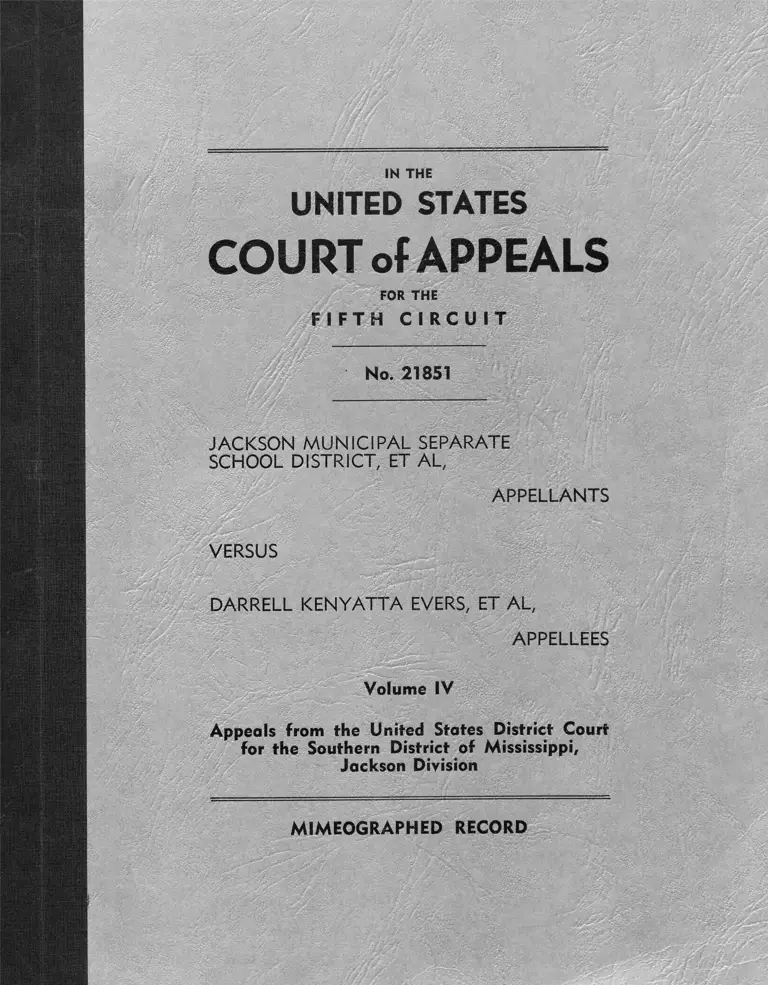

Jackson Municipal Separate School District v. Evers Mimeographed Record Vol. IV

Public Court Documents

August 11, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson Municipal Separate School District v. Evers Mimeographed Record Vol. IV, 1964. 72defad9-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/91db91d5-d531-4586-82ae-f0c954d147eb/jackson-municipal-separate-school-district-v-evers-mimeographed-record-vol-iv. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES

COURT of APPEALS

FOR THE

F I F T H C I R C U I T

No. 21851

JACKSON MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL,

APPELLANTS

VERSUS

DARRELL KENYATTA EVERS, ET AL,

APPELLEES

Volume IV

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi,

Jackson Division

MIMEOGRAPHED RECORD

VOLUME IV

I N D E X

Page

No

Transcript of

Testimony

Intervenor's

Intervener's

Intervenor's

Intervenor's

Intervenor's

Testimony

HALFORD SNYDER

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

Exhibit

No

No

No

No

No

Plaintiff's Exhibit No 4

Othnion of the Court

Judgment

Desegregation Plan

Plaintiffs' Object:ons

by Defendant Boards

Notice of Appeal

WHITAKER

24: Sheet

25• Sample Trac

26: Sample

27 A: Article

27 B: Article

Report

: ngs

Tracings

to Desegregation Plans Filed

and Motion for Revised Plans

Appeal Bond

Notice of Appeal

Appeal Bond

Order Tentatively Overruling Objections to Plan

Designation of Contents of Record on Appeal

Motion for Original Exhibits To Be Sent To The

Appellate Court

Designation of Record on Appeal

Order for Original Exhibits To Be Sent To The

Appellate Court

Certificate of Service

574

574

5^4

584

608

613

645

646

650

652

653

655

657

662

66

66

669

(R-693 contd.)

VOLUME IV

574

After Recess

HALFORD SNYDER WHITAKER, called as a witness and having been

duly sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. PITTMAN;

Q, Dr. Whitaker, are you a medical doctor?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Would you state, please, your qualifications as a medical doctor?

And give your full name.

A. Halford Snyder Whitaker. As qualifications, I have a Doctor of

Medicine degree, and trained in pediatrics, certified as a specia

list in pediatrics.

Q. You are a board-qualified pediatrician? (R-594)

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Go ahead.

A. And trained in neurology and EEG, electroencephalogram.

MR. PITTMAN: Your Honor, we tender into the record

the sheet containing the qualifications and training and experience,

and the publications by Dr. Whitaker.

THE COURT: Let them be received in evidence.

(Same received in evidence and marked as Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 24)

(Exhibit is not copied because by order of the Court the original is to

be inspected.)

Q. Dr. Whitaker, what is neurology?

A. Neurology is the study of the brain and its functions, both at the

575

bedside and as a basic discipline of biology.

Q. Since your graduation from medical school and since your intern

ship and since your residency in pediatrics, how many years have

you had in child neurology?

A. Three; two in neurology and one in pediatric neurology.

Q. Where are you now located?

A. I am on the faculty of the Bowman Gray School of Medicine in

North Carolina.

Q. On the faculty?

A. Yes.

Q. How old -- - Before we get into the detailed questions, how old is

the method of study of the brain by electricity, electric study of

the brain? How old is that system?

A. Well, the first signals from an animal brain were picked up about in

1379. It has been used on humans since the late (11-695) 1930's,

and is used every day in hospitals now, since the second world

war.

Q. Doctor, we have been studying the brains of adults, but the ones

involved in this case are children, school children.

And I will ask you if there is any relation between the

brain size of children and the intelligence in children?

A. This has been studied, and actually there is a better correlation

between estimation of this cranial capacity and intelligence in six

year old school children than there is in these adult studies.

Q. Now, when you say "better correlation, " do you mean that the

differences are greater in a six year old school child than they are

576

in adults?

A. These were done on English school children, all white, and they

showed the greater the cranial capacity, the greater the intelli

gence, and it was measured by several tests.

Q. Are you in agreement with those studies?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Are there any ways to test the working of the brain other than in

telligence and sociological testing that we have shown in the trial

of this case ?

A. Well, a more direct way, it gives a little different information, is

this electroencephalogram, which I would be more interested in,

and this is a way like the electrocardiogram which we are familiar

with.

Q. The electrocardiogram is for the heart? And the (R-696) electro

encephalogram is for the brain?

A. Yes, sir. There's the difference. And in this case, the wires

are applied over the head and electricity given off by the brain, —

the brain functions as an electric organ -- these signals are then

carried into a machine where they are amplified a million times,

and they write out a record, and this record makes a different

pattern, and these can be either analyzed by another machine or

we can just by direct inspection look at them and compare them

with the patterns that have been worked out several years ago by

Gibbs at Harvard and in his 25 or 30 years since. This shows

normal and abnormal patterns.

Q. Now, this is purely for demonstration, and not for evidence in this

577

case, but did you not hand me some samples of tracings made by

the electroencephalograph?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Would you just take one or two of these and explain for the record

how that machine records these impulses from the brain.

A. These are examples showing the paper which runs through the

machine itself. The recording, of course, is done without the

benefit of anyone between the patient and the machine, and the

machine records this directly.

This shows a child, In a somewhat irregular behavior of

the waves and these big waves that you see here. (R-697)

And this then shows an adult pattern, as you can see,

shows a little more regular and faster and smaller waves running

across the page. And when the eyes are opened, all this stops.

MR, PITTMAN; I believe I will identify the first one for

the record.

THE COURT: Very well.

MR, PITTMAN: We tender it for identification and part

of the record. That is a sample of a child’s brain study.

THE COURT: Let It be received in evidence.

(Same received in evidence and marked as Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 251

(Exhibit is not copied because by order of the Court the original is to

be inspected.)

Q. Now, the next one you have in your hand is a sample of a study of

an adult brain?

A. Yes, sir. This one I just showed you.

578

Q. Are you through illustrating with this to the Court?

A. Yes.

MR. PITTMAN: I. offer this latter study of an adult brain

for identification and for the record.

THE COURT: Let it be received in evidence.

(Same received in evidence and marked as Intervenor's Exhibit No 26)

(Exhibit is not copied because by order of the Court the original is to

be inspected.)

Q. Now, in making those recordings, what enters into it? Is that one

voluntarily or involuntarily, or does the one who is doing the r e

cording have any effect upon what those papers show?

A. The patients, you might say, make their own recordings, and these

are just electrical signals from the different parts of (R-698) the

brain, picked up by the machine, magnified and written down.

Q. Have standards of normal patterns been worked out over the last

few years so that that gives a reliable indication of certain phenom

ena?

A. Standards have been worked out and are published, and there is an

international classification of these that we all use. And these

can be done by interpretation of the record, by only counting the

number of each type of wave and writing them down, and compar

ing it with the standard.

Q. Are there any studies which have compared the white and Negro

brains by the methods that you speak of or by electrophysiology?

A. Not in the U. S. There are some studies on African natives and

African white persons, and these are, one, by the doctors of the

579

French Army, some of whom were electroencephalographers.

Q. Are you familiar with that article, or have you studied it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you have a copy of that article in French?

A. Yes.

Q. It was published originally in French, was it not?

A. Yes.

Q. Gan you read French?

A. Yes, sir. I have to.

Q. Did you translate that article from French to English?

A. I did for myself; I didn’t make any translation. (A-699)

Q. Do you have a copy of a translation?

A. Yes.

Q. Is that translation correct?

A. It agrees with the original.

Q. Go ahead with your testimony about that study.

A. Well, these findings in this study, which was done with standard

technique and the standard in the international classifications, and

some of them were interpreted with the electronic analyzer --

that is, the doctor didn't interpret them.

On the natives, on the blacks in Africa, shows one-third

of them had none of this normal adult rhythm that we show is the

normal that we usually expect.

Q,. Now, who were these Africans that were being tested that the

article reports on?

A. These were some troops in the French Army. They were natives

530

who had been taken into the Army, screened for the absence of

nervous system disease, of course, and any evidence of severe

head trauma, anything that might have influenced the record.

These hundred soldiers had been in the Army several years and

had been talien to France, and this is where they happened to be

when the study was made, in Marseille, France. They had no

evidence of central nervous system disease, and the study was

made just as a comparison,

Q. Then you state to the Court what were the findings. (R-700)

A. Well, they say one-third of them did not show the normal alpha

ryhthm that we see as expected in the adults.

Q. Will you explain what the alpha rhythm is? And you might point to

one in one of these exhibits so that the Court can better understand

it.

A. This is a normal adult record (indicating) showing this alpha waves

all across the record and disappearing when the eyes are opened

to come back when the eyes are closed.

Q. Explain to the Court what you mean by when the eyes are opened

and when the eyes are closed, the mechanics of it when testing.

A. During this type of recording, we have the patient lying undisturb

ed, with his eyes closed. At times during the recording we have

him open his eyes, and then close them. Very rarely the alpha

wave will persist. They nearly always go away when the eyes are

open. This is supposed to be because the tension of the eyes is

arrested at that time. Otherwise, the alpha waves persist through

the record. This is the adult pattern. As we said, the child does

581

not have this but has a much slower and more irregular record.

Q. Now, the normal white subject, when his eyes are closed, what do

these lines show? Are they rhythmic?

A. This is a rhythm that runs all across the record in the channels

that are connected to the back of the head. (R-701)

Q. All right. When the eyes are opened, then what do those lines

reveal?

A. Well, when the eyes are open, the pattern goes away. The patient

is no longer resting alert with his eyes closed. It has been seen

in a few psychiatric subjects — and this is reported in the Stand

ards book on EEG, in Hill & Parks, it's called — there are some

of these psychiatric subjects whose alpha will go right on when

their eyes are open, and this is supposed to mean a lack of visual

imagery, and it's not the usual abstract capacity that other people

have.

Q. What is the difference between the recordings for those 100 African

troopers and the normal recordings of the normal group of whites?

I believe that appears on page 116 of your translation —- I mean

on page 16.

A. The things that were found, the most striking is that when the eyes

are open, the alpha waves rarely disappear; as I say, this does

happen in white people rarely, that they will persist, but the oppo

site was true in these troops in that the alpha wave nearly always

went right on.

I think the way it was said in the conclusions of the author

was, the author that did this study, it said:

582

"The stoppage reaction Is rarely complete, sometimes

entirely absent.11

As I said, this is exactly the opposite to the white normal.

( R - 702)

Q. Now, what were the conclusions of this study?

A. Well, to quote the author, he says:

", .We find ourselves in the presence of an accumulation of

facts, not very detailed, but very expressive in their raw nature."

He calls attention to the fact that this would be, except for

this business of the alpha persisting, which he says there can be

no explanation for, if it occurred in all the white persons, — ex

cept for this complete difference, he says that the other chcarac-

teristics in these tracings could be explained as immaturity, be

cause this sort of record is seen in very young children. There

is a lot of the slow waves, the regular slowing; he found this in

most of these tracings, and he even found what we call delta waves,

which are never present in the adult white tracings.

Q. Would it be accurate or inaccurate to say that this study reveals

evidence of immaturity or childishness in a third of the subjects

studied?

A. Well, I would modify that to say that two-thirds of them showed

much more alpha than would be seen in the normal adult tracing

that we are used to seeing here in the white race. Otherwise, this

statement would be true. This still does not explain the complete

difference in alpha blocking which he can have no explanation for;

it's Just different in these troops tested than in any of the studies

583

that have (R-703) been done on the white race.

Q, I ask you this: Are the slow delta waves which were found in the

examination of those Africans — not all of them, but a large por

tion of them — are those ever seen in white people except during

childhood?

A. No.

Q. Now, I read you from page 16, and ask you if that finding is a

correct finding in the French text which you translated:

"In tailing account of the norms established for the white

race in important statistical studies to which we shall now return,

we found only 42% of the tracings in accord with the established

c rite ria ."

Is that right? Page 16 of the translation.

A. Well, It is true that he found only 42 percent of the tracings in

accord with the established criteria, but he takes into account that

some of these 42 would be abnormal in the normal adult white,

but they still wouldn't be completely normal tracings.

Q. Now, on page 2l I read to you:

"This system of interpretation of the electrical details of

the brain of subjects of the Negro race would bring biological con

firmation to the work of psychiatric and psychological specialists

on the black continent, who have already known for a long time a

psychological immaturity with a tendency toward paroxysmal

manifestations in the case (R-704) of the forest Negro. "

A. What page is that on?

Q. Page 21. Is that a correct interpretation or, rather, translation,

584

and is that conclusion in accordance with your opinion as a special

ist?

A. Yes.

MR. PITTMAN: We tender, if Your Honor please, for the

record and for admission in evidence both the article in the origi

nal French and the translation. The article is entitled "Introduc

tion to the otudy of the Electrophysiology of the African Negro, "

by P. Gailais and G. Miletto.

THE COURT: Let it be marked, and received in evidence.

MR. BELL: Your Honor, let us enter a special objection

for all these studies of the African Negro. I have great difficulty

seeing the relevancy of these studies on the African to the Ameri

can Negro in Mississippi.

THE COURT: I will adhere to the ruling heretofore made

and overrule the objection.

MR. PITTMAN: If Your Honor please, I would suggest a

number 27-A and 27-B.

THE COURT: Very well.

(Same received in evidence and marked as Intervenor's Exhibits No.

27-A and 27-B, respectively)

(Exhibits are not copied because by order of the Court the original is

to be inspected.)

Q. So is it or not true, Doctor, that this study shows a distinct and

confirmed difference in the physiology of the brain? (R-705)

A. Yes.

Q. Is there anything further you wish to state, anything I have failed

to ask you about In connection with the electrical studies?

A. Parts of this have been tested and confirmed, and I apologize that

there are no studies I know of in the United States.

Q. And that is the only study you know of in the world, of the Negro

brain as compared with the white?

A. Well, that and the second study done in another part of Africa,

and this was reported on by the United Nations in one of their re

ports, this same study. These are the only ones I know of.

Q. And are all of those studies in accord to the effect that the electro

physiology of the Negro brain is different from that of the white

brain?

A. Yes.

MR. PITTMAN: That is all.

THE COURT: Any questions by the defendants?

MR. CANNADA: No, sir.

THE COURT: Any cross examination?

MR. BELL: No cross examination, Your Honor, and the

same motion to strike the testimony.

THE COURT: For the reasons herefofore stated, I will

overrule the motion.

MR. CANNADA: May we say, on behalf of the defendants,

(R-706)

we would adopt for the defendants the testimony of the intervenors.

THE COURT: Yes, sir.

(Witness excused)

THE COURT: Do you rest?

MR. PITTMAN: We rest. The interveners rest.

585

586

THE COURT: I believe all the defendants have now rested.

Is that correct.

MR. CANNADA: Yes, sir.

THE COURT: Any rebuttal?

MR. BELL; Yes, sir. We would, of course, renew our

motion to strike from consideration in the record all the testimony

of the intervenors for the reasons that we gave; and in rebuttal to

the testimony given in the main by defendants -- although I guess

the Court can consider this for whatever relevancy it has through

out the consideration of this case — plaintiffs offer in rebuttal as

an exhibit to their case a part of the evidence admitted in the case

of the United Mates of America vs. Mate of Mississippi, Civil

Action No. 3312, the record in this court, southern District of

Mississippi; that part of the evidence which is a comparison of the

education of Negro and white children, white persons, in Missis

sippi, from 1880 until 1963.

Now, this data was gathered by the United States Govern

ment In response to interrogatories of certain of the (R-707) de

fendants for the State of Mississippi. The data was gathered from

official state reports. It is fairly lengthy, but I would, as a part

of my motion to have it admitted, like to point out some of the

highlights of the information that it contains.

On page 2 of the report, it points out that white public

school teachers in Mississippi "were and are more highly trained

than Negro teachers. "

It points out further that this is during this whole period of

587

the study from 1890 to the present. It points out moreover that

white public school teachers in Mississippi were and are more

highly paid than Negro school teachers.

As just one example of a lot of the figures it gives, in

1949-1950 white school teachers averaged $1,805.69 per year,

and Negro teachers averaged $710. 56 per year.

More white teachers are provided for white child in attend

ance than for Negro child in attendance in the public schools of

Mississippi.

In 1931-32 school year the ratio for whites in white schools

was 23 students for each teacher. During the same period, the

ratio was for Negroes 34 students for each teacher.

In 1961-62 the ratio for whites was still 23 pupils for each

teacher, and for Negroes it had dropped down only to 28.5 pupils

for each teacher.

MR. WATKINS: Pardon me. I want to object to this. It

(R-708)

is clearly inadmissible. We don't know who assembled this data.

We have no opportunity to cross examine, and counsel is merely

reading into the record certain statistics alleged to have been ob

tained by some person from some report, and he will later cite

from the record those statistics as though it were evidence. We

don't think this has any place in this record. He is reading what

are alleged to be findings by some unknown person in some other

lawsuit.

MR. BELL: I think, if counsel was listening, I pointed out

that what I'm reading Is part of the record in a case which was

588

heard in this court, and on that basis alone the court could take

judicial notice of it.

But, moreover, I pointed out that the records were com

piled by the United States Government in answer to interrogatories

posed by officials of the State of Mississippi in all of the material

and all of it set forth here is taken from state reports by state

officials of the State of Mississippi.

Now, we have gone through here since Monday, almost

three full days of testimony, all of which has been adopted by the

defendants, aimed at showing that Negroes are inferior, are less

educable, have lower scholastic achievement, and in all other

manner are greatly inferior to white pupils in Mississippi, and

therefore, a classification based on race, which is the way they

are operating (R-709) their schools, is. justified under the Con

stitution.

I am pointing out in sole rebuttal, and I think I am entitled

to a few minutes after they have taken a few days, one exhibit

which I think throws more light on inequality between Negro and

white pupils than all of the information that they have shown.

THE COURT: Of course, the Court takes judicial know

ledge of its own record and will take judicial knowledge of such

record, as it is required to take. However, unless it was offered

in evidence, as you are doing now, I doubt if testimony taken would

be considered as part of the record of which judicial knowledge

would be taken.

But at any rate, I will let the offer be made and be a part of

589

the record here in this court in another case — to which I assume

these parties in this case were not parties to that suit? What was

the style of that?

MR. BELL: I think that was the United States versus

State of Mississippi. I don't know the exact --- Well, to the ex

tent that the attorney-general's office is representing the school

board in accordance with state statute, then to that extent the

parties would be the same. But I don't think that similar parties

— Similar parties is not one of the prerequisites.

THE COURT: I will permit you to make the offer and

(R-710)

call the attention of the Court to the high spots, and I will reserve

ruling upon the objections of the defendant as to whether or not it

is admissible, because I am not sure whether that can be admitted

in that form or not.

So I reserve ruling upon that objection.

MR. GANNADA: Is he permitted to continue to read his

resume of what the report shows, which we have never seen and

had no opportunity to cross examine on?

THE COURT: Of course, the record, you are offering —

MR. GANNADA: We have never seen it.

THE COURT: Let counsel opposite see that.

MR. BELL: All right. We haven't seen a great deal of

some of the latter testimony and we made no similar objection.

Now, I would like to, if I may, if this is going to be so much prob

lem, continue my resume and then offer this in evidence and let

them see it for whatever purposes they want, and perhaps after the

590

luncheon break they can make any further objection to It that they

may see fit.

MR. WATKINS: Your Honor, may I ask a question? I'm

not too familiar with the record, but, Counsel, isn't it a fact that

the Court in that case from which that was taken refused to con

sider the answers to those interrogatories you are reading as evi

dence, and disregarded it in that lawsuit?

MR. BELL; I'm not certain that that Is so. I am certain

(R-711)

the case is presently pending on appeal before the U. S. Supreme

Court.

MR. WATKINS: Do you know whether or not the Court

that heard that case considered that as evidence in the case?

MR, BELL; Now, I'm not going to answer these questions.

THE COURT; The record will show ---

MR. CANNADA: The other question I would like to ask is,

we are here dealing with the students of the Jackson Municipal

Separate School District,

MR. BELL: I ’m going to get to that if they will give me the

courtesy —

MR. CANNADA: and insofar as I have heard, he is

talking about a report we have never seen.

THE COURT: Let me see what you are offering.

{Same is handed to Court)

THE COURT: I see here "Answers to Interrogatories of

Mate of Mississippi; Mrs. Pauline Easley, Circuit Clerk and

Registrar of Claiborne County; J. W. Smith, Circuit Clerk and

591

Registrar of Coahoma County; T. E. Wiggins, Circuit Clerk and

Registrar of Lowndes County.i!

Now, Coahoma County and Lowndes County are not in this

district.

MR. BELL: I believe that the United States Government

in that voting suit, which is the type of suit it was, had (R-712)

joined all of the counties, if I'm not mistaken, as party defendants,

and these particular party defendants had requested interrogatories

and asked the United States Government to explain allegations in

the complaint to the effect that the educational opportunities pro

vided Negro children in the State of Mississippi were greatly in

ferior to the educational opportunities provided white children in

the State of Mississippi. Now, in response to those interrogator

ies, the Government compiled this document, compiled it com

pletely from official state reports, reports of the superintendents

state

of the/educational system, reports of the state body to the legis

lature biannual reports, a 20-year study and various other studies

made by officials of the State of Mississippi.

THE COURT: This document that you have handed me

which you propose to offer in evidence, is this an exact copy of

the answers to the interrogatories?

MR. BELL: I believe it is, Your Honor, though I imagine

that can be checked. I received it from an agent of the United

States Government. Although I didn't think it would be necessary

to have the seal mark on, I certainly can get that without difficulty,

or it can be checked with the original in the clerk's office.

592

THE COURT: I think the interrogatories ought to be,

because this looks like a lot of argument and stuff here (R-713)

rather than copy.

ME. BELL; No, Your Honor, it is all factual material.

THE COURT: In direct answers?

MR. BELL: That's right. The question was -- There was

a series of interrogatories, and I believe most of this data was in

in answer to one particular interrogatory, which requested the

plaintiff, the United States Government, to explain an allegation in

the complaint to the effect that Negro educational opportunities in

Mississippi were inferior to the educational opportunities provided

for white children. Nov;, all of the materials there is not argu

ment, but the support for the allegation.

THE COURT: And is the language of the answer?

MR. BE LL: And is the language of the — Most of it is

quotes or statistical quotes.

MR. SHAND3: Have you examined that statement to verify

it?

MR. BELL: what statement?

THE COURT: Just a minute, Gentlemen. One at a time.

I think he ought to be able to verify that these are direct

answers. I certainly don't know, and it's not certified to by the

clerk of the Court; but I will let you offer it and, of course, you

can offer it and it will be come a part of the record whether it is

competent or not; but I will exclude it just on statements here be

cause I could not take judicial notice of the records of the Northern

593(R-714)

District of Mississippi because they are not available to me. Now,

the Court will take judicial knowledge of any record in its own

district because they are available to the Court for whatever they

may be worth.

So I think you should just offer them in evidence and —

MR. BELL: Your Honor, I should like to — I would like

to have the courtesy that I extended to counsel for defendants and

counsel for intervenors during the period since about eleven

o'clock on Monday morning when we rested our case, and that is

to at least permit me to make my offer on this proof, and at the

conclusion of it then hear the various objections. I think I am en

titled to that.

THE COURT: Yes, you are entitled to that, and I am

going to let you do that.

I am going to let him epitomize what that —

MR. PITTMAN; If Your Honor please, I'd like to make a

statement in behalf of the intervenors.

MR. BELL: Your Honor, I have been interrupted in the

course of this thing.

THE COURT: Well, they are entitled to be heard, and then

I will hear you.

MR. PITTMAN: We object to the admission of any evidence

or any material derived from any case in which the intervenors

were not parties and with which they were not (R-715) concerned

and in which they had no opportunity to present contrary facts or

evidence of any kind. We insist that under the law we are only

594

bound In cases where the same parties where the evidence was

offered, where we were parties, or where we were represented by

parties. And in the matter he speaks of, we were not represented

directly or indirectly, and had no opportunity to consider or refute

any of the material in it; so we think now it will be incompetent as

far as the interveners are concerned.

THE COURT: Very well. Let the objection be noted, and

I will reserve ruling on it.

Of course, the statement he is reading into the record now,

if there is a variance from anything in the exhibit — if the exhibit

should be received in evidence, the exhibit will control, and the

balance of the statement would be disregarded. He is simply mak

ing this as an offer; rather than reading the testimony he is offer

ing at this time, he is epitomizing the parts he expects or desires

to call attention to.

You may proceed.

MR. BELL: Thank you, Your Honor.

As I was indicating, during this whole period of the statis

tics and other reports that have been compiled, more money was

spent for the instruction of white children in (R-716) the State of

Mississippi than for Negro children. In 1929-1930 the record In

dicates that an average of $40.42 was spent for each white child,

while $7.45 was spent for the education of each Negro child.

By 1956-57 that figure had increased to $128. 50 per white

child, and had Increased for the Negro child to 378.70.

By 1960-61 the figure for the white children was an average

595

of $173.42; for Negroes, $117.10.

Now, with particular reference to the defendants in this

case, the exhibit shows at pages 8 to 10 that during the year 1961-

62 that the defendants boards here spent in the education of each

child above the stale minimum program: The Jackson board, first

of all, for white children, $149.64, and for Negro children,

$106.37; for the Leake County board, that figure was above the

state minimum for the white children, $48.85, and for Negro

children, $17.37. For the Biloxi Separate .school District, the

figure was for the same period, 1961-62, for white children

$128.92, and for Negro children, $86.25.

Now, the figures here give the breakdown for every school

district in Mississippi, and I certainly won't try to read them all,

but other typical ones include Clarksdale (R-717) and Coahoma

County school district, where the Court can take judicial notice

where school desegregation suits have been filed: for the Clarks

dale Separate School District, the figure for 1961-62 was $146.06

for the white children, and $25.07 for Negroes. For Coahoma

County School District, the figure was $139.33 for each white

child, and for each Negro child, $12.74.

Just a few other examples: From Madison County, our

neighboring county here, the figure was $171.24 for the white

children, while for Negroes it was per child $4.35.

For neighboring Rankin County, we have for white children,

$72.71 per child, and for Negro children,$14.78, per child.

And one more, Yazoo County, located about 50 miles away,

596

for each white child above the minimum, it was $245.55, for each

white child, and for Negroes for each child, $2.92.

The report points out at pages 11 to 14 that in 1954-55

every school district in Mississippi spent more money to educate

white children than it did for Negro children. During that period

the Jackson school board, according to the figures given here,

spent $217.00 for the education of each white pupil and $157.00 for

the education of each Negro pupil. The Leake County board spent

$169 for the education of each white pupil, and $104 for the educa

tion of each Negro. The Biloxi school board spent $191 for the

education of each (R-718) white pupil, and $141 for the education

of each Negro.

The county average in county school boards during this

period throughout the state was $161 for each white child, and

$87 for each Negro.

For special or separate school districts In the amount of

money, it was generally a little more. The average was, through

out the state, $181 for each white child, and $106 for each Negro

child.

On page 14, the report taken from official state documents

indicates that white children have generally longer school terms

than Negroes throughout the State of Mississippi. They give the

data bringing up to date to the 1961-62 situation, which showed that

in that period only 2 white school districts had school terms of

eight months, while during the same period 103 Negro school dis

tricts had school terms of eight months. During the same period

597

637 white school districts enfoyed full nine-month school terms.

During that same period only 399 Negro school districts enjoyed

full nine-month school terms.

On page 15 of the report, it shows that in 1910 Mississippi

decided that consolidation of rural schools would improve education

for children, and the report on that indicates the several reasons

the determination to consolidate was made — indicated that if the

teacher was responsible for only one or at the most two (R-719)

grades, it would be easier to secure good teachers with profession

al training. It was an economy toconsolidate the schools. "Pupils

are more interested in school and therefore attend more frequently

and remain in school and go on to high school. The entire curri

culum can be enriched. The school building will be much superior.

Consolidation offers the bases for the solution of more of the rural

school problems than anything that has yet been offered."

Based on these findings, consolidation of the Mississippi

schools began in 1910. However, between 1910 and 1930, while

many white school districts were consolidated, no Negro school

district was consolidated during that period. Therefore, as of

1931, there were 959 consolidated white school districts, and

789 unconsolidated white school districts at that stage. During the

same period there were only 16 consolidated Negro school dis

tricts, and 3,484 unconsolidated Negro school districts. The re

port points out that the consolidation of Negro schools did not

really get underway until after the Brown decision in 1954, forty

years after consolidation of white schools.

598

On pages 16 and 17 of the report, it points out that at all

times in Mississippi "secondary education has been made available

to more white children than Negro children, " even though there

have always been more Negro children than white children of

school age. And the report goes on to give (11-720) the breakdown

in statistics supporting that statement.

On page 18 the report indicates, giving statistics in sup -

port, that at all times "more white high schools than Negro high

schools "have been accredited by either the State of Mississippi or

by regional accrediting association.

On pages 20-23 of the report there are breakdowns indicat

ing the wide variation in college training available to whites and

Negroes in Mississippi.

On page 24 we offer that particularly with reference to the

fact that school teachers who have to have the training generally

get it within the state, then come, return to either Negro or white

school.

On page 24 of the report it points out that officers of the

state government have recognized that the public educational facil

ities provided for Negroes were inferior to those provided for

whites. Now, it gives first of all a number of quotes from various

governors of the State of Mississippi concerning education, and I

certainly won't try to read them all. And I think it does show an

improvement from the early quote by Governor Vardaman back in

1907 when he is reported to have said, "Here is what I promised to

do. I said if you elect me Governor and elect a legislature in

599

sympathy with me that I would submit to the people of Mississippi

an amendment to the State Constitution which would control the

distribution of a public school fund so (R-721) as to stop the use

less expenditure In the black counties." . . .

THE COURT: Let me ask you there about that now.

Is that an answer by these registrars?

MR. BELL: No, Your Honor. I was confused on that

point. The registrars didn't give the answers. The registrars

filed the interrogatories, and the Government, in answer to the

registrars' interrogatories, provided these answers, but they

provided them fro m -----

THE COURT: Well, I'm going to sustain the objection to

the introduction of that, because I was admitting it upon the theory

of a statement against interest. Those are self-serving declara

tions.

MR. BELL: They are not self-serving declarations, Your

Honor, when they are made by officials of the State of Mississippi.

If anything, they are declarations against interest, at least in this

regard.

THE COURT: As I understand, the State of Mississippi

didn't give that information.

MR. BELL: But the information that was given, Your

Honor, is taken from official reports of the state of Mississippi.

THE COURT: I ’d like to see that report where it is stated.

Anyway, that wouldn't be competent. I knew Governor Vardanian

personally. He was campaigning, and that's (R-722) what he was

600

doing in the campaign.

MR. BELL; Well, let me strike the statement of Governor

Vardaman which tends to be a campaign statement and go along to

another statement, Your Honor, which was the only other one I

was going to mention.

THE COURT: I believe I will sustain the objection to that

document in the form it is. I would like to see those records of

which I could take judicial notice, rather than to have a copy that

is prepared by someone other than the official custodian of the

records. Now, if that had been certified to by the clerk of the

court, then, of course, under that doctrine a certificate would

certify to its accuracy.

MR. BELL: Well, Your Honor, let me interrupt, if I may.

I wasn't basing the admissibility of this solely on the fact

that it was admitted in another case. I think that was a certainly

firm basis, and if you prefer it on there, there would certainly be

no difficulty in getting the clerk within a very few minutes, I'm

sure, unless the record has already been sent up on appeal, to have

her certify that this is a true copy of the document that was filed.

Now, it certainly purports to be a true copy from the face of it,

I'm sure you will admit. Moreover, you have the word of counsel

and I have certainly, in all of the years I've been coming (R-723)

down here, and I pride myself on being a member of this court,

and I say to the Court that it is a true and correct document of a

part of a record of a case in this court. Now, we have not, during

all these few days, required any of these books, this information,

601

or at least these graphs which have been shown to the Court, to be

certified in any such fashion. We assumed that because these

attorneys who are members of this bar had indicated that they were

what they were, that that was good enough. Now, I can't see why

we should have to be held to a higher standard, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Because I'm not satisfied, when you start

quoting there from political speeches, that — -

MR. BELL: — It was a statement to the legislature, Your

Honor; not a political speech.

Let me return to the statistics and let me ask you to re

serve the decision until I finish.

THE COURT: All right, you can do that.

MR. WATKINS: Your Honor, before he commences, let

me point out once more that these are statements of some person

with the United States, purported to have been lifted from the pub

lic records of Mississippi. Now, we are not complaining because

we don't think that is what is reflected in the records of that law*

suit, but we complain, as we would have in that lawsuit if there

had been public facts alleged (R-724) to have been produced by

the United States without certification of the facts as produced;

and we think the record is being cluttered by a form of evidence

that is not proper here, would not even have been proper in the

case in which it was offered, and it is my advice from the attorney-

general's office that it was ruled incompetent in that case for the

very reason I am stating. And I don't think we ought to clutter the

record with alleged facts found by the United s ta te s -----

602

THE COURT: Well, I believe he's nearly through, aren't

you?

MR. BELL: I am, Your Honor. May I continue?

Now, every two years the State Superintendent of Public

Education in Mississippi reports to the Mississippi Legislature.

Following are excerpts from some of the reports, many of which

are set out in fairly good detail here. These reports indicate that

the public education for Negroes has been inferior to that provided

for whites.

Now, an early report, at page 25 and 26 of the exhibit, is

quoted, as follows:

"In many counties, particularly in rural areas, Negro

children are forced to attend school in mere shacks or in church

houses... Consolidation has done away with practically all of the

one and two-teacher schools. In fact, this year there are less

than ten percent of the white children CR-725) of the rural dis

tricts attending these old type schools. The other ninety percent

have the advantage of modern high schools, in many of which, not

only the college preparatory course is given but also work in vo

cational agriculture, home economics and business training... "

Now, this was taken from the Biennial Report 1929-31,

page 11 of that report.

Another report indicated that 83 percent of all colored

children enrolled in school were in open country rural schools,

the great majority of which were of the one and two teacher type so

common in Mississippi in both races prior to 1910.

603

That statement was taken from a document titled TWENTY

YEARS OF PROGRESS 1910-1930 AND A BIENNIAL SURVEY

SCHOLASTIC YEARS 1929-30 AND 1930-31 OF PUBLIC EDUCA

TION IN MISSISSIPPI, Issued by W. F, Bond, State Superintendent

of Education.

Now, from the same report by W. F. Bond, he states at

page 90:

"The quality of work done in the school room by the ma

jority of Negro teachers would not rank very high when measured

by any acceptable minimum known to the leaders in educational

thought. There is a growing sentiment among the white people

and the Negroes in Mississippi favorable to improvement in school

plants, in the training of Negro teachers which will guarantee a

better quality of work in (R-726) the schoolrooms for the Negro

ra c e ."

At Page 28 from the Biennial Report to the State Legisla

ture of 1933-35, the report says:

"There is also dire need for school furniture and teaching

materials - comfortable seating facilities, stoves, blackboards,

erasers, crayon, supplementary reading materials, maps, flash

cards, and charts.

"In many of the 3,763 colored schools of the state there is

not a decent specimen of any one of the above-mentioned items.

In hundreds of rural schools there are just four blank, unpainted

wails, a few old rickety benches, an old stove propped up on brick

bats, and two or three boards nailed together and painted black for

604

a blackboard. In many cases, this constitutes the sum total of the

furniture and teaching equipment. “

Now, the next biennial report, for 1935-37, indicates that

"high school advantages for Negroes in Mississippi are very

meager. Ninety-four percent of the educable Negro population of

high school age is not in school. .. .There are twenty-eight

counties in Mississippi which do not have any recognized high

school facilities for Negroes. Fifteen counties make absolutely

no provision whatever for high school training of Negro children.

Of the fifty-four recognized four-year high schools for Negroes,

fifteen are privately owned and supported... Only eighteen Negro

high schools in Mississippi.. . " — (R-727)

THE COURT: I believe, Mr. Bell, that is all I care to

hear from that. You may offer it and let It be marked as an exhi

bit. And I sustain the objection to it and will exclude it from con

sideration in reaching a judgment in this case for more reasons

than one.

I think it is not between the parties that are in this litiga

tion, and they are not bound by it extra judiciary. I would have

to be proven by witnesses because there is a lot of material in

there that is so far back that —

MR. BELL: Well, I was going to bring it up to date, Your

Honor, if you will give me the minimum of the time that the de

fendants have had. I was going to bring that right up to date and

show that there has been an improvement but that there was an

admission by the state legislators up to the present day that there

605

was still a lot of work to be done before the Negro schools in the

State of Mississippi are on a par with the white schools. I was

going to bring it up to date.

Now, we’ve gone clear back to dark Africa to show that

Negroes are inferior.

THE COURT: Yes, but that was by competent evidence,

and I don’t think this is competent. If you had competent evidence

here to establish those facts where it would be subject to cross

examination by the attorneys in this case who are conducting the

trial of this case and were not connected-----that is all the inter

veners; none of them (R-728) were connected with that case, and

none of the other defendants were connected with those cases. So

it is not admissible in evidence.

Now, part of it would be competent testimony if a witness

were here subject to cross examination, but the document in its

present form is not competent, in my judgment, and for that rea

son I will sustain the objection; but, of course, it will go into the

record, and if I am wrong about it, then it would be erroneous and

the courts would probably reverse any judgment that I might ren

der in the case, or they might, considering the record itself,

might conclude that whatever judgment I rule would be correct re

gardless of whether that was competent or not competent.

Now, you have your record complete by offering it in evi

dence, and since I am going to exclude it for the reasons I have

stated, it is not necessary for you to take up any more time read

ing that. So I sustain the objection to it.

606

MR, BELL: Gould I make a further statement, Your

Honor ?

THE COURT: Yes.

MR, BELL: When we returned with this case from the

Fifth Circuit and the motion to intervene was made, and the plain

tiffs objected to such intervention on the basis that it was a mere

attempt to relitigate the issues that had already been settled in the

Brown decision by the United 0 7 2 8 ) Jtates .supreme Court, and

moreover that subsequent similar efforts had been knocked out

by

either/the district courts or by the Fifth Circuit in a number of

cases, the Court pointed out that nevertheless the intervenors

were entitled to make their record.

Now, one of the bases for objection to permitting that rec

ord to be made, notwithstanding the unlikelihood that the position

could be sustained, was that we had to face the fact that Missis

sippi not accidentally was the last of the states to initiate at least

token desegregation, and that we were hopeful that this inevitable

change could be brought about in as peaceful and orderly fashion

as possible. We pointed out to the Court that the introduction of

all of this mass of material, with die importance that the case has

generally and with the tremendous play that it will be given in the

newspapers and news media all over the state, as it has been given,

would rnalee more difficult rather than less difficult the job of

initiating and carrying through compliance with the d upreme

Court's decision of 1954.

Now, it was the opinion of plaintiffs, as we have pointed

607

out several times, one, that all of such data was irrelevant to the

issues in this case, and

THE COURT: I have already ruled on those and-----

MR. BELL: —- This is preparatory to making a further

(R-730)

offer on that, Your Honor, if I may.

THE COURT: Well, you needn’t remind me of everything

— Certainly I don't want to shut you off on anything you want to

say that I don't already know, but we have taken up some time

here, and we have two more cases to go on to pretty soon, so

what is it?

MR. BE LL: Well, what I want to say is that it was my

hope to, since we must be cognizant of the fact, while we are try

ing the case to the Gourt, that the Mate of Mississippi as a whole

is following this case with avid interest, to at least be able to in

dicate part of the reason, in rebuttal, why, if there is any dis

parity between Negro and white achievement, our reason for be

lieving that it is due to the long and rather unhappy history of un

equal educational opportunities that have been provided for Negro

children in the state.

For that reason we wish to offer this, and it is for that

reason that I would permit the Court to permit counsel for plain

tiff under Rule 43-c of the Federal Rules to continue making their

offer in order to make the record. —

THE COURT: Well, you've already made your offer, and

it is there and speaks for itself. And I have sustained the objection

for the reasons I've already stated, so it is not necessary to make

608

any offer of what you expect to prove, because there it Is. Now,

if you have any other evidence you (R-731) want to offer in re

buttal, of course, if it is competent certainly you are entitled to

get it in and I will hear It. I don’t want to shut you off from any

thing I think you’re entitled to and which you want to do; that's not

my purpose. I am simply ruling here upon the admissibility of

evidence, and in my judgment that is not admissible. As I say,

though, it is there and will become a part of the record upon

appeal in the event there is an appeal from whatever decision the

Court makes; so it is there, and it is not necessary for you to say

anything on what is in there.

MR. BELL: All right, Your Honor. We have nothing

further.

THE COURT: Very well. Let it be marked, and the

objection is sustained.

(Same was marked as Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 4.)

THE COURT: It will not be taken into consideration in

reaching a judgment in this case.

Anything further, Mr. Bell?

MR, BELL: Nothing further, Your Honor. The plaintiffs

rest.

THE COURT: I believe everybody has rested. Is that

correct?

MR. LEONARD: The intervenors rest, but I would like to

point out in connection with the statement which has just been made

to the Court by Mr. Bell that we have (R-732) presented here in

609

court the actual witnesses and documents of which we spoke, and

we put them on under the common laws of evidence, and that they

were open both to rebuttal and to cross examination, and that Mr.

Bell's choice not to cross examine has not been a matter of cour

tesy on his part; it has been an unwillingness to meet this proof.

THE COURT: Very well. Everyone has his statement in

the record now.

It is nearly adjourning time, so let me ask about the next

case, the Leake County case.

MR. BELL: Yes, Your Honor. On this case, counsel for

plaintiffs and defendants have been making some efforts to shorten

the proceeding by preparing and agreeing to a group of stipulated

facts which can be submitted to the Court as the factual record of

this case, some of which would be attached, exhibits, and other

documents.

Now, we are in sort of a draft stage at this time, and I

believe with a little longer than ordinary lunch break —-

THE COURT: Very weH. What about three o'clock?

MR. WELLS: I think by three o'clock we will be able to

come into court with a complete stipulation and eliminate any tak

ing of any evidence whatsoever.

THE COURT: Very well. The next case will be the Biloxi

case. What about it?

MR. WATKINS: I don't think the Biloxi case will take

(R-733)

long, Your Honor. We will probably have one witness. We expect

to adopt the evidence offered in the Jackson case, to which I under*

610

stand counsel has no objection.

MR. BELL: We have the regular objection to Its compe

tency, but we have no further objection.

THE COURT: I see. You rely upon the same objections

you have heretofore entered.

All right. Let me ask this now: I don’t believe these cases

have been consolidated, but as I recall it, it was agreed here when

we started that all the evidence that was taken in this Jackson case,

so far as was relevant to the issues in the other cases, would be

considered as apart of the evidence in each one of those cases.

Is that the understanding?

the

MR. BELL: I think that was/under standing.

THE COURT: Is that your understanding?

ME. WATKINS: Yes, sir.

MR. BELL: I did have one witness on the Biloxi case, one

of the plaintiffs who is a medical doctor and one of the few Negro

medical doctors in the community, and I thought there was a

possibility he could get on today, but rather than take his time, I

had asked him to be prepared for nine o’clock tomorrow morning.

Now, I was wondering if we could finish up Leake County this

afternoon and if it would be possible to come back tomorrow morn

ing with the hope of finishing up within a very few hours. (R-734)

MR-. WATKINS: If counsel would reduce to writing what

Dr. Mason — - Is it Dr. Mason?

MR. BELL: Yes.

MR. WATKINS: — what Dr. Mason plans to testify to,

611

we may be able to agree that would be his testimony. I would like

to get through this afternoon on the Biloxi case, if we could.

THE COURT: I imagine you know, in substance, what

Dr. Mason would testify to, don't you, Mr. Bell?

ME. BELL: Yes, Your Honor. I was hoping the Court

would get a chance to see Dr. Mason, in view —

THE COURT; Oh, I know Dr. Mason.

MR, BELL: Oh, you know Dr. Mason? Then — Some

times I begin to wonder myself, after two or three days of this,

and I thought Dr. Mason was a prime example to the contrary.

— But if you know him, perhaps we could get together and make

stipulations similar to those that we are preparing with Mr. Wells.

THE COURT; Very well. We will take a recess until

three o'clock, and see what you can work out in that time.

(Whereupon the court was recessed until 3:00 P . M . )

* Sf- *

612(R-735)

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN

DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI, JACKSON DIVISION

DARRELL KENYATTA EVERS and KEENE DENISE EVERS,

minors, by MEDGAR W. EVERS and MRS. MYRL3E

B. EVERS, their parents and next friends, ET AL,

Plaintiffs,

Vs.

JACKSON MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT,

KIRBY P. WALKER, Superintendent of Jackson City

Schools; LESTER ALVIS, Chairman; C‘. II. KING,

Vice-Chairman; LAMAR. NOBLE, Secretary; V/. G. MIZE

and J. W, UNDERWOOD, Members,

Defendants,

JIMMY PRIMOS, ET AL,

Intervenors.

(Civil Action No. 3379)

COURT REPORTERS CERTIFICATE

I, D. B. JORDAN, Official Court Reporter for the Southern

District of Mississippi, do hereby certify that the above-entitled cause

came on for hearing before the Honorable S. C. Mize, United States

District Judge for the Southern District of Mississippi, at Jackson,

Mississippi, in the Jackson Division, on the 18th day of May, 1964,

and that the foregoing pages constitute a true and correct transcript

of the testimony and proceedings.

WITNESS my signature, this the 2nd day of July, 1964.

/ s / D. B. Jordan

D. B. JORDAN

* * *

CR-170)

OPINION OF THE COURT

(Title omitted-Filed July 7, 1964)

613

The complaint in this case was filed on behalf of several minors

and their parents. It was alleged that the plaintiffs were all members

of the Negro race and that the action was being brought on their behalf

and on behalf of all other Negro children and their parents in Jackson,

Mississippi.

The defendants are designated as the Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District, the individual members of the Board of Trustees

of the Jackson Municipal Separate School District, and Kirby P. "Walk

er, Superintendent of Schools.

The relief sought was that the defendants be enjoined from

operating a compulsory biracial school system in Jackson, Mississippi,

and in the alternative that the Court order the defendants to present a

plan to "desegregate" the schools within the Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District.

iifter alleging that the defendants did maintain a compulsory

biracial school system in the Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, the plaintiffs alleged that they were "injured by the refusal of

the defendants to cease operation of a compulsory biracial school

system in Jackson, Mississippi." It was further (R-171) alleged that

the operation of a compulsory biracial school system violated the

rights of the plaintiffs and the members of the class which they pur

ported to represent which were secured to them by the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Fed

eral Constitution.

614

The defendants filed their answer to the complaint. In this

answer it was admitted that, with respect to all schools under their

supervision and control, there were no schools attended by members

of both the white race and the Negro race. The defendants denied,

however, that they maintained or operated a compulsory biracial

school system and further denied that the fact that no schools were

attended by members of both the white race and the Negro race came

into existence pursuant to the requirements of state law and denied

that such condition was continued, perpetuated or maintained as a mat

ter of state lav;, policy, custom or usage.

Defendants, in their answer, alleged that the schools in said

District were being operated, to the best of their abilities, for the

benefit and best interest of all pupils of the District; that the defen

dants were and are vested with the exercise of judgment and discretion

in connection with the assignment of pupils to schools within the Dis

trict, and that many factors were taken into consideration in connection

with their exercise of such judgment and discretion; that one of the

factors taken into consideration was the differences and disparities

between the ethnic group allegedly represented by plaintiffs and the

Caucasian children in the District; that such racial differences are

factual in nature, and, as such, can and should be taken into considera

tion by the defendants in the operation of the schools of the District.

In short, the defendants planted themselves firmly upon the

proposition that instead of being injured by separate schools for the

members of the Negro and white races that, as a matter of fact, such

schools were advantageous to the pupils of both races, and that in the

615

conduct and exercise of their responsibility and duties (R-172) in

connection with the operation of said schools the defendants were act

ing within their judgment and discretion in taking into consideration the

educational characteristics of the Negro and white races.

Thus, the issues were clearly presented by the pleadings. The

fact that members of both the white and the Negro races do not attend

the same schools was alleged by the plaintiffs and admitted by the de

fendants. Thus, this is not an issue. The controlling issues are:

1. Are the plaintiffs, or the members of the class they pur

port to represent, as a matter of fact, injured by the

operation of separate schools for the races in the Jackson

Municipal Separate School District?

2. Are those charged with the responsibility for the mainte

nance and operation of the schools within the Jackson

Municipal Separate School District authorized to take into

consideration the educational characteristics of the mem

bers of the Negro race and the educational characteristics

of the members of the white race in connection with the

operation of such schools?

A petition to intervene was filed in this cause on behalf of cer

tain minor children and their parents. In this petition it was alleged

that the intervenors were members of the white race. The petition to

intervene was approved by this Court and the intervenors filed an ans

wer to the complaint, oaid answer sets forth in some detail alleged

differences and disparities between members of the Negro race and

members of the white race and alleges affirmatively that should those

616

charged with the responsibility of the operation and maintenance of the

schools of the Jackson Municipal Separate School District ignore or not

consider such differences between members of the two races such

would cause irreparable injury to the intervenors and to the class they

purported to represent, as (R-173) well as to the plaintiffs and to the

class the plaintiffs purported to represent.

Plaintiffs therefore contend that the operation of separate

schools for members of the Negro race and members of the white race

has resulted and is resulting in injury to the members of the Negro

race. The intervenors contend that the operation of schools which

members of both the white race and the Negro race attend would result

in irreparable damage to the members of both races. The defendants,

those charged with the responsibility of the operation and maintenance

of said schools, contend that the educational characteristics of and the

differences between the two races should be taken into consideration

as factual matters and the schools operated in such a manner as to give

good faith consideration to these factors, along with all other proper

factors.

If, as a matter of law, there are no circumstances or conditions

under which the educational characteristics of or the differences be

tween the white race and the Negro race as they now exist within the

bounds of the Jackson Municipal Separate School District can be con

sidered by those charged with the responsibility of administering such

schools, then the preliminary injunction heretofore entered by this

Court should be made final. On the other hand, if those charged with

the responsibility of administering such schools are to be permitted to

617

take into consideration, along with all other proper factors, the educa

tional characteristics of or the differences between the members of

the white and Negro races, then the issues were clearly presented by

the pleadings.

The Court was and is of the opinion that in the exercise of their

discretion and judgment, such exercise being in good faith and in ac

cord with the principles heretofore enunciated by the Supreme Court

of the United States, those responsible for the administration of such

schools may take into consideration, along with all other proper fac

tors, the educational characteristics of or the differences between the

members of any ethnic groups, including the (R-174) Negro race and

the white race. Therefore, the Court permitted the parties to submit

evidence pertaining to the issues as heretofore set forth.

Plaintiffs submitted as witnesses the parents of some of the

minor plaintiffs. The substance of the testimony by such witnesses

was to the effect that they desired that their children attend "mixed

schools, " that is, attend schools that were attended by members of

both the white race and the Negro race. These witnesses testified that

even though it could be shown that separate schools for the members

of the Negro race and members of the white race were actually educa

tionally superior for their children, that, nevertheless, such would

not be satisfactory since they desired that their children attend "mixed

schools. " These witnesses testified, without exception, that their

business contacts, their employers, their customers and their busi

ness associates were all members of the Negro race. Yet, they in

sisted that their children attend "mixed schools. "

618

The plaintiffs also placed on the stand Kirby P. Walker, Super

intendent of Schools of the Jackson Municipal Separate School District.

Mr. Walker testified, in substance, that there were no schools in the

District attended by members of both the white and Negro races, inso

far as he knew, and that in making temporary assignments to the

schools he did take into consideration the educational characteristics

of and the differences between the members of the white and Negro

races. He testified that of the approximately 37,000 pupils enrolled

in the Jackson Municipal oeparate school District, approximately 6093

were members of the white race and approximately 4093 were members

of the Negro race; that because of the numbers in both races it was

economically possible and feasible to have separate schools for the

races, and that this was, in his opinion as an educator, highly advis

able and desirable. He further testified that there were no real differ

ences between the facilities, program of studies or courses available

as between the various (R-175) schools within the District, whether

they be attended by members of the white race or attended by members

of the Negro race.

The plaintiffs then introduced the interrogatories propounded

by plaintiffs to defendants and the answers to these interrogatories by

the defendants.

Thereupon, the plaintiffs rested. There was no showing nor,

in fact, was there any effort to show that the separate schools were

unequal or that such actually caused injury to the plaintiffs or to any

members of the class which the plaintiffs purported to represent. The

plaintiffs obviously rested their case upon the contention and position

619

that any recognition or cognizance of the characteristics of or differ

ences between the members of the various races was not within the

scope of the judgment or discretion to be exercised by those charged

with the responsibility of administering the schools.

There was no evidence or testimony showing or tending to show

injury resulting to plaintiffs or the class purportedly represented by

plaintiffs resulting from separate schools, nor was there any showing

of any advantage or merit in the so-called "mixed schools" insofar as

plaintiffs were concerned.

Defendants first presented evidence pertaining to the scholastic

achievement and mental ability {!. ■>.) of the members of the white and

Negro races, as reflected by the records maintained by the Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, and pertaining to such pupils within

such District. These records disclose that there is a wide discrepancy

between the scholastic achievement and the mental ability, as shown by

recognized tests used nationally.

These records disclosed a noticeable and substantial difference

in the scholastic achievement of the members of the Negro and white

races and a difference in the scores attained on the nationally recog

nized mental ability tests, with the white pupils consistently scoring

above the national average and the Negro pupils consistently scoring

below the national average. The disparity between the members

(R-176)

of the two races as reflected by the mental ability tests became more

pronounced as the age of the pupils increased.

J. D. Barker testified that this same difference or disparity

existed between the members of the two races for as far back as the

620

records of the Jackson Municipal Separate school District were avail

able, which was for a number of years.

This testimony was placed into the record without any objection,

cross-examination or contradiction other than the objection as to ma

teriality or relevancy.

The defendants then presented two witnesses who testified as to

facts concerning public schools that have been changed from all-white

or all-Negro schools to schools serving members of both races. Con

gressman John Bell Williams, as a member of a Congressional Inves

tigating Committee, testified concerning the results found by his Com

mittee investigating the public schools of Washington, D. C. after same

had been "mixed” for a number of years. His testimony was to the

effect that the schools, after the "mixing," were inferior to the schools

which had been operated in such a manner as to have the members of

the two races attend separate schools. Unquestionably, his testimony

was to the effect that the "mixing" of the races in the schools had been

injurious to members of both races.

W. S. Milburn testified as a retired educator. He had served

as principal of a large high school in Louisville, Kentucky. He had

been President of the Southern Association of Colleges and Universi

ties, had served as a member of the Board of Aldermen of Louisville,

Kentucky for a number of years, and had extensive experience as an

educator. He testified that the "mixing" of the races in Male High

School of Louisville, Kentucky had resulted in a deterioration of the

school and injury to members of both races.

Thus, the uncontradicted testimony was to the effect that the

621

"mixing" of the races in the same school was injurious to the members

of both races. (R-177)

The defendants also called as witnesses Kirby P. Walker,

Superintendent of Schools of the Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, and James Gooden, retired Director of the Negro Schools of

the Jackson Municipal Separate School District. Each of these wit

nesses testified, without contradiction, that, in his judgment, as an

educator, the operation of separate schools for the members of the

Negro and white races within the bounds of the Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District was for the best interest of the members of both

races.

Mr. Gooden is a member of the Negro race. He holds a mas

te r 's degree in school administration from Northwestern University,

Evanston, Illinois, and has served in the public schools of the Jackson

Municipal Separate ochool District for many years. He testified that,

in his opinion, the schools in the Jackson Municipal separate school

District were excellent and that it was best for the members of both

races that they attend separate schools.

Mr. Walker testified that he had been connected with a study

made by M. V. O'Shea, Professor of Education, University of Wiscon

sin, the results of which were published in 1927, pertaining to the

school systems within the State of Mississippi; that such study had been

impartially and fairly made and that the ultimate recommendation and

conclusion of such study was to the effect that separate schools for

members of the white and Negro races were desirable. He further

testified that this study disclosed a marked and substantial difference

622

in the scholastic achievement and mental ability of the members of the

two races, as reflected by various tests given.

Mr. Walker further testified that as Superintendent of the pub

lic schools of the Jackson Municipal Separate School District he has

been and is conscious of the differences between the members of the

two races, and that In 1954 when the Board of Trustees of the Jackson

Municipal Separate School District placed upon him the responsibility