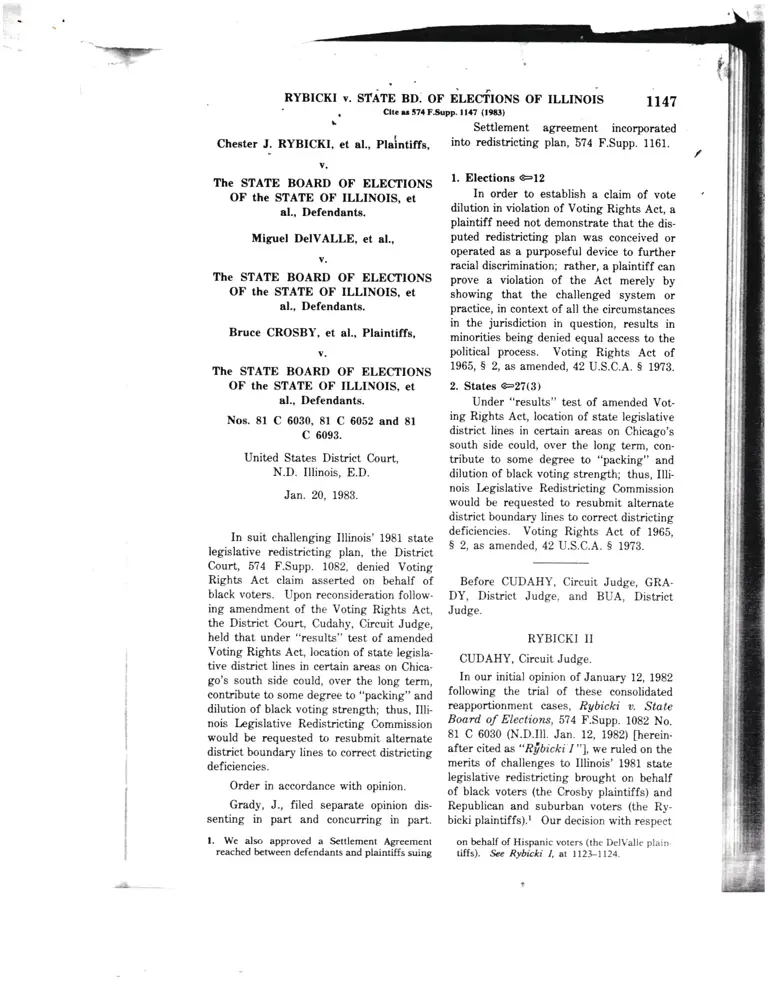

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections of Illinois Court Opinion

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 20, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Rybicki v. State Board of Elections of Illinois Court Opinion, 1983. e336e0e2-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/920ed3ac-dabd-44d7-918c-a65a831364fe/rybicki-v-state-board-of-elections-of-illinois-court-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

]--

Chest€r J. RYBICKI, et al., Plalntiffe,

Y.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECIIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS, et

al., Defendants.

Miguel DeIVALLE, et al.,

Y.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS, et

al., Defendants.

Bruce CROSBY, et al., Plaintiffs,

v.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS, et

al., Defendants.

Noe. 8l C 6030, 8l C 6052 and 8l

c 6093.

United States District Court,

N.D. Illinois, E.D.

Jan. 20, 1983.

In suit challenging Illinois' 1981 state

legislative redistricting plan, the District

Courl, 574 F.Supp. 1082, denied Voting

Rights Act claim asserted on behalf of

black voters. Upon reconsideration follow-

ing amendment of the Voting Rights Act,

tle District Court, Cudahy, Circuit Judge,

held that under "results" test of amended

Voting Rights Act, location of state legisla-

tive district lines in certain areas on Chica-

go's south side could, over the long term,

contribute to some degree to "packing" and

dilution of black voting strength; thus, Illi-

nois Legislative Redistricting Commission

would be requested to resubmit alternate

district boundary lines to eorrect distrieting

deficiencies.

Order in accordance with opinion.

Grady, J., filed separate opinion dis-

senting in part and concurring in part.

l. We also approved a S€ttlemenl Agreement

reached between defendants and plaintiffs suing

RYBICKI V. STITN BD: OT N.INSiTOXS OF ILLINOIS

. Clt u37{FSupp. ltaT (t9t3)

tt47

Settlement agreement incor.porated

into redistricting plan, 5?4 F.Supp. 1161.

l. Electione €=12

In order to establish a claim of vote

dilution in violation of Voting Rights Act, a

plaintiff need not demonstrate that the dis-

puted redistricting plan was conceived or

operated as a purposeful deviee to further

racial discrimination; rather, a plaintiff can

prove a violation of the Act merely by

showing that the challenged system or

practice, in context of all the eircumstances

in the jurisdiction in question, results in

minorities being denied equal aecess to the

political process. Voting Rights Aet of

1965, 5 2, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. S 1973.

2. States @27$)

Under "results" test of amended Vot-

ing Rights Act, location of state legislative

district lines in certain areas on Chicago's

south side could, over the long term, con-

tribute to some degree to "packing" and

dilution of black voting strength; thus, IIli-

nois Legislative Redistricting Commission

would be requested to resubmit alternate

distriet boundary lines to correct districting

deficiencies. Voting Rights Act of 1965,

5 2, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A. S 1973.

Before CUDAHY, Circuit Judge, GRA-

DY, District Judge, and BUA, District

Judge.

RYBICKI II

CUDAHY, Circuit Judge.

In our initial opinion of January 12, L982

following the trial of these consolidated

reapportionment cases, Rybicki o. State

Board of Elections, 574 F.Supp. 1082 No.

81 C 6030 (N.D.II. Jan. 12, 1982) [herein-

after cited as "Rfibicki.f "], we ruled on the

merits of challenges to Illinois' 1981 state

legislative redistricting brought on behalf

of black voters (the Crosby plaintiffs) and

Republican and suburban voters (the Ry-

bieki plaintiffs).r Our decision with respect

on behalf of Hispanic voters (the DelValle plain.

tiffs). See Rybicki I, at tl23-t124.

1r48 5?4 FEDERAL SUPPI,EMENT

L

to the Crosby claims at the time ol Rybicki' in the specific areas we identifi below so

r was, we believe, *""""tly based in the as to correct these apparent districting de /

Supreme C,ourt's most recent analysis of ficiencies'

roting dilution claims as eet fofih in City

of AiU;te a. Bold.en,446 U.S. 55, 100 S'Ct'

1490, 64 L.Ed.zd lZ OS80l. l,tt"t our Jan- I'

;il'it opilion was issued, however, and Il1 The legislative history of the

*tii" *" were reviewing the Crosby plain- amended Voting Rights Act clearly indi'

tiffs' motion for reconsideration of the catcs that claims of vote dilution do come

Crosby decision, C,ongress extended and within the scope of the Act, S.Rep' No. 417,

amended the Voting Rights Aet.z C,onse g?th Cong., 2d Sess. 30 n. 120 (1982). Fur-

quently, in response to the Crosby plain- ther, in order to prove vote dilution, plain-

tiff"',"qo"tt, we have decided to reevalu- tiffsneednotdemonstrate that "the disput-

ate those of the Crosby plaintiffs' claims

"a

pU. was 'conceived or operatcd as [a]

tlrat we found wanting under the Bo-lden porpor"fU devic[e] to further racial . . .

criteria to determine whether t'he evidence iiscrlmination."'

-Bold,en,

446 U.S. at 66,

may be sufficient to show a possible viola-

iOO S.Ct. at 14g9. Instead, plaintiffs can

tion of the amended Voting Rights Act'

As a result of this reevaluation, we are prove a violation of the Act merely by

tentatively of the view that in certain spe- showing "that the challenged system or

cificareasonChicago'sSouthSidethepractice'inthecgntytofallthecircum'

location of the district lines, in connection iton"u in the jurisdiction in question'

wit}rhighlyconcentratedblackdistricts,resultsinminoritiesbeingdeniedequal

ind in light of all the relevant factors, may access to the political process'" S'Rep' No'

besuspectunderthe"results"testofthe4l?'g?thCong''2dSess'ZI'U'S'Code

amended Ac; rr,erero.q we request the c,ong. & Admin.News 1982, p. 205 (empha-

Crcmmission to redraw certain district lines sis supplied).3 Under this "results" test,

vided, That nothing in this section establishes

a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion

in the PoPulation.

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub'L'

Ho. si-zol, S 3, 1982 u.s.coDE coNG' & AD'

NEWS (95 Stat.) l3l, 134 (ro be codified at 42

u.s.c. s 1973).

3. The House Judiciary Committee Report on the

Voting Rights Act extension and amendment

sp"cifttty identifies districting plans as within

tir. ."op. bf section 2. H.R'Rep' No' 227' 97th

Cong., tst Scss. 30-31 (1981)' This Report was

bai upon H.R. 3112, 97th Cong', lst-S€ss'

(1981), ; bill whose wording was slightlv differ-

ent from the language ultimately enacted into

law. The Senate Judiciary Comminee Report'

however, characterized the House and Scnate

bills as "virtually identlcal'" S'Rep' No' 417'

97th Cong., 2d Sess. 3 11982). Defendants do-

noi aitprr-.'"., this juncture" the applicability of.

the amended Section 2 to this casrc' Defendanls'

Memorandum in Response to August 6' 1982

Court Order ar 3. We do not think that applying

Section 2 ro the present districting plan presents

issues of retroactive application because our

analysis focuses on the fulure effects of this

nlan in lhe 1984, 1986, 1988, and 1990 elections'

'kc Herelord Independent *h@l District v' kll

aS.r r.S"'pp. 143 (il-D.Tex.1978) (mem') (uphold'

2. On June 29, 1982, the President signed -the--e*i"nriot of the Voting Rights Act, as amended'

The legislative history states that one ol the

"[i*,li.t

in amending Section 2 was "to clearly

"*iluti.tr the standards intended by Congress for

orovins a violation of that section'" S'Rep' No'

i1t, sltn cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1982), U's'Code

Cong. & Admin.News 1982, pp' 177 ' 178'

The amended Section 2 reads as follows:

Sec. 2. (a) No voting qualification or pre-

reouisite to voting or standard, practice' or

priedure shall be imposed or applied by any

Stat. ot political suMivision in a manner

*hi.h t"t,rltt in a denial or abridgement of

the right of any citizen of the United States to

,ote ot account of race or color, or in contra-

vention of the guarantees set forth in section

l(f)(2), as provided in subscction (b)'

'6)'l

"i6tati"n

of subsection (a) is estab-

tished if, based on the totality of circum$anc-

es, it is shown that the political process€s

leading to nomination or election in the State

o. poiiti""l suMivision are not equally open

io

-participation by members of a class of

citiiens piotected by subsection (a) in that its

members have less opportunitS' than othcr

members of the electorate to panicipate in thc

oolitical Drocess and to elect representative'

of their ciroice. The extenl to u'hich mcml'' r'

of a protected class have been elected to offi'c

in the State or political suMivision is or:'

circumstance whiih may be considered' l:"

___---!E i.,.&_--

t

V

. RyBrcI(r v. srATE BD. OF

"rjrron. oF rlr,.rNors 1r4g

we must "assess the impaet "ff;;t"l*'# ffl, and r? ias revised) and house

l91sed structure or practice on the basis of districts ?8, 24,81, BB (as revised) and B6 r'

objective factors, ratrer than mak[e] a de. (as revised).', Memorandum in support

termination about the motivations which of Crosby plaintiffs, post_Triat Motion 4.lay behind its adoption or maintenance.', The .,result,, in terms of concentration ofId. Congress has provided us with I non- bhck populations in voting districts is

exclusive list of objective factors to guide clear; in connection with this concenhation

us in determining whether in a partieular the alleged correspondence between district

case the challenged practice or structure fines and racial divisions (characterized forviolates Section 2. See S.Rep. No. 41?, rhetorical purposes as a ..wall,,) must be97th Crcng., 2d Sess. 2V29 & nn. 114-18

(1e82). r-hese factors are applied to this ffiH:',r'JrTn::;r#l, t:-ffit j:"*:case in the following section. tions and correspondence between election

IL district and housing segregation demarca-

rz) The focus of continuing eoncern in tions)' either singly or in combination, and

this case is on the South Side districts.

in the context of Chicago political realities,

The south side majority black house dis- violate the voting Rights Act'

tricts contain high concentrations of blacks, We think it deserves notice at the outset

much greater than 65% of the district popu- that the complaints we address here have

lation-the percentage generally presumed their root in the extremely marked housing

necessary for a minority population to elect segregation on Chicago's South Side. A

a representative of their choice.a Further, large area on the South Side is more than

the Crosby plaintiffs eontended at trial that 85% blaek. See Pl.Ex. 12. Given this seg-

"[t]he boundary lines for Commission regation and the territorial basis of repre-

house districts 17, 18, 23,24,25,31,33 and sentation under our system, it is inevitable,

34 trace in great part the boundaries of the absent the most outlandish gerrymander-

heavy black concentration in Chicago." ing, that at least the voting districts in the

Crosby Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of interior of this area will be very heavily

.Fact No. 97. They contend now that "the black. obviously, we deplore the extreml

map adopted by the Court imposes the degree of housing segregation in this area;

same racial wall as the Commission's origi- but there is no eyidence before us that the

nal map, only now involving senate dis- design of voting districts has any impaet on

ing application of Section 5 to election proce-

dures adopted prior to, but administered in elec-

tions subsequent to, the effective date of the

Voting Rights Acr).

{. The 65% figure is a general guideline which

has been used by the Department of Justice,

reapportionment experts and the courts as a

measure of the minority population in a district

needed for minority voters to have a meaningful

opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice.

See Mississiryi v. United States, 49O F.Supp. 569

(D.D.C.1979), afl d, 444 U.S. 1050, l0o S.ct. 994,

62 L.EA.2d 739 (1980). The 65% guideline,

which the Supreme Coun characterized as .,rea-

sonable" in United Jewish Organizations, Inc. v.

Carey, 430 U.S. l,+4, 164, 97 S.Cr. 996, 1009, Sl

L.Ed.2d 229 (1977), takes inro accounr the

younger median population age and the lower

voter registration and turnout of minoritv citi-

zens.

Testimony in the instant case esrablished thar

Representative Madigan and his staff u'ere

made aware of the 65% guideline b1' Mr- Br:i.-.

their consultant, during the summer of 1981.

(Tr. at 1957). At trial, witnesses for both sides

referred approvingly of the 65% figure. (Tsui,

Tr. al 26-27; Newhouse, Tr. ar 623; Hofeller,

Tr. at 40344; Brace, Tr. at 1956-57). More-

over, defendants'expert testified that the 65%

guideline had been used in state reapportion-

menl and redistricting. (Brace, Tr. at 1957).

The 65% standard was also referred to in the

recent opinion of the three-judge court in In re

Illinois Congressional Districts Reapportionment

Casas, No. 8l C 1395, slip op. ar t9 (N.D.Ill.

l98l), afld sub nom. McClory v. Otto, 454 tJ.S.

1130, 102 S.Cr. 985, 7l L.EA.2d 284 (t982).

We think it appropriate, however, to take judi-

cial notice of the fact that in the March l9g2

Democratic primary election for the new Senate

District 18, a disrricr redrawn at the behesr of

this courl ro include a 660.,6 black population,

black candidates wel.e unsuccessful in their ef-

forts to unseat lhe *'hite incumbent S€nator.

. -,ri

674 FEDERAL SUPPLEMENT1150

bousing. Our ability in a redistricting case

to deal with the problem is't]rus limitcd at

best. L

Crcngress has suggested that we consider

certain factors in decidiirg a challenge to

the rrceult of an election practice or struc-

ture. The factors are Bet forth in the fol-

lowing excerpt from a Senate committee

report:

l' the extent of any history of offi-

cial discrimination in the state or politi-

cal subdivision that touched the right

of the members of the minority group

to register, to vote, or otherwise to

participate in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the

elections of the state or political subdi-

vision is racially polarized;

3. the extent to which the state or

political subdivision has used unusually

large election districts, majority vote

requirements, anti-single shot provi-

sions, or other voting practices or pro

cedures that may enhance the opportu-

nity for discrimination against the mi-

nority group;

4. if there is a candidate slating

process, whether the members of the

minority group have been denied ae-

cess to that process;

5. the extent to which members of

the minority group in the state or polit-

ical subdivision bear the effeets of dis-

crimination in such areas as education,

employment and health, which hinder

their ability to participate effectively in

the political proeess;

6. whether political campaigns have

been characterized by overt or subtle

racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of

the minority group have been elected

to public office in the jurisdiction.

Additional factors that in some cases

have had probative value as part of plain-

tiffs' evidence to establish a violation

are:

whether there is a significant lack of

responsiveness on the part of elected

officials to the partieularized needs of

the members of the minority group.

r'

whether the policy underlying the

atate or political subdiyision'e uge of

, such voting qualification, prerequisite' to voting, or stsndard, practice or pne

cedure is tenuous.

While these enumerated factors will

often be the most relevant ones, in some

cases other factors will be indicative of

the alleged dilution.

The cases demonstrate, and the C,om-

mittee intends that there is no require

ment that any particular number of fac-

tors be proved, or that a majority of

them point one way or the other.

S.Rep. No. 41?, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 28-29

(1982), U.S.Code Cong. & Admin.News

1982, pp. 206-207 (footnotes omitted).

These factors are in turn derived from

the analysis in White o. Regester,4l2 U.S.

755, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 3? L.Ed.2d 314 (1973).

ln lVhite, the Supreme Court reviewed a

three-judge district court's invalidation of

the Texas 1970 legislative reapportionment.

The significance of the case for present

purposes rests in the approach taken by

the district court and followed by the Su-

preme Court in invalidating multimember

districts in Dallas and Bexar Counties. In

looking at Dallas County, the district court

considered the history of Texas politics,

including the effect of official racial dis-

crimination on the right of blacks to regis-

ter and vote and to participate in the demo-

cratic process; the use of a system that

enhanced the opportunity for racial dis-

crimination; the fact that since Reconstruc-

tion there had been only two blacks in the

Dallas County delegation to the Texas

House of Representatives; the fact that a

white{ominated organization effeetively

controlled Democratic Party candidate slat-

ing in Dallas County and thus had great

influence over elections; the fact that this

organization did not need the support of

blacks to win elections and tlerefore did

not concern itself with political and other

needs and aspirations of blaeks; and the

fact that this organization used racial cam-

paign tactics in white precincts to defeat

black-supported candidates. The district

court thus concluded that "'the black com-

InU

psr

lec

erl

Po,

ir4

u.f

suI

I

lye

fi(

sig

dis

ica

tior

oth

xar

tiv,

of

tnr.

I

eoll

Croi

Cor

eou

cirr

z

a

n

p

wh

S.C

A

12,

dis(

ele<

ider

Reg

prir

unl:

the

Der

c:Ig

con

mur

5.

r(l

xar

Ir

ir

s

The Supreme Court affirmed the district

court's invalidation of the Dallas and Bexar

Counties multimember districts. The

C,ourt accorded deference to the district

court's careful consideration of the factual

circumstances, and said with respect to Be-

xar County,

[o]n the record before us, we are not

inclined to overturn these findings, repre-

senting as they do a blend of history and

an intensely local appraisal of the design

and impact of the Bexar C,ounty multi

member district in the light of past and

present reality, political and otherwise.

White a. Regester, 412 U.S. at 769-70, 93

S.Ct. at 2341.

1151

On the other side of the balance, we

must give weight to our findings of pur-

poseful dilution of black voting strength in

the Commission's actions with respect to

senate districts 14, 1? and 18 of the Com-

mission Plan. We found that the immedi-

ofe purpose of the Commission in drawing

these districts was primarily to preserve

the ineumbencies of two white state Sena-

tors. We also found that "this pnocess was

so intimately intertwined with, and depend-

ent on, racial discrimination and dilution of

minority voting strength that purposeful

dilution has been clearly demonstrated in

the construction of C,ommission senate dis-

tricts 14, 1? and 18." Rybicki 1, at 1110.

,t

RYBICKI v. STATE'BD. OF ELECIIONS OF ILLINOIS

m-

n}

ri

.l,i

t

tof

h

lu

I

rix

DE

of

tc-

of

n

ra

rm

S.

D.

a

of

rt.

nt

)y

u-

BT

ln

?1

a,

t-

B.

t>

rt

B.

e-

IE

a

a

v

t-

rt

a

,f

d

'r

e

l-

t

t

l-

Utc.. JTaf3npp. ttlrT (t9t3)

munity has been effectively excluded frcm blaek voters' needs and aspirations. In-

participition in thc Democratic primary se deed, rather than jgnoring causes helpful

lection process,' .-. . and was therefore gez- to blacks, the Democratic Party in Illinois

erolly not permittcd to e'ftter into the has been a prineipbl exponent of civil rights

potitical process in a reliable and rnean' legislation and of social legislation imp6r-

ingful rnonner." White o. Regestcr, 412 tant to blacks. Also, unlike the situation in

U.S. at ?6?, 93 S.Ct. at 2340 (emphasis Whitn o. Regester, many blacks have been

supplied). elected to local office in Chieago and to

A similar approach was employed in ana- state and national positions representing

lyzing the legality of the multimember dis- Chicago. Sixteen of the fifty aldermen in

trict in Bexar County, a county with a Chicago are black. Thirteen of the thirty-

significant Hispanic community. Here the five state representatives and five of the

district court considered the effect on polit- nineteen state senators from Chicago dis-

ical participation of discrimination in educa- tricts are black. Three of the seven U.S.

tion, employment, economics, health, and Representatives from Chicago are black.

other areas. The court concluded that "Be' In sum, there has been no systematic exclu-

xar County Mexican-Americans 'are effec- sion of blacks from, or denial of meaning-

tively removed from the political processes ful participation in, Chicago's and lllinois'

of Bexar [County] . . . .' " White o. Reges- political processes comparable to the histo

tnr, 412 U.S. at ?69, 93 S.Ct. at 2341. ry outlined in White a. Regester.s

As we noted in our opinion of January

12, 1982, the record before us does not we also note our finding that on chica-

disclose a history of overt and systematic go's west Side there was fracturing and

electoral discrimination comparable to that packing of blacks' the net effect of which

identified by the district court in white o. was "the purposeful dilution of black vot-

Regester. Illinois has never had a white ing strength on the west Side by at least

primary or a poll tax. Most importantly, one House District'" Id' aL ll12'

unlike the organization then in control of Further, we should take into account, to

the Democratic Party in Dallas County, the the extent_relevant, in deciding whether the

Democratic organization in the City oi Ct i- challenged praitices deny blacks an equal

cago depends upon the support of the black opportunity to participate in the political

eommunit5r to win elections and therefore process and to eleet representatives of

must be at least somewhat responsive to their choice, the poor socireconomic condi

5. Following the issuance of this Opinion, Ha- Mayor of Chicago, the first black to hold the

rold Washinglon was, on April 12, 1983, elected office.

ia

6?1 FEDERAL EUPPLEMENT1162

tions, unemployment, and traditionally low

voter registration affl icting blact' communi-

tiea in Chicago. Also, we recognize 8s part,

of this c8se'8 "totqJity of circumstancls,',

that employment or other discrimination

hes been alleged and/or proveD in such

City units as the Chicago police Depart-

ment, the Chicago Housing Authority, the

Chicago Board of Education, the Chicago

Public Ubrary, and the Chicago park Dis-

trict. See id. at 1120.

Although it is unclear that the Crosby

plaintiffs are arguing the issue of ,,pack-

ing" through excessive concentration of mi-

nority populations in voting districts except

insofar as these concentrated districts may

have boundaries that follow racial divi-

sions, we think we should first consider

whether the present concentration of

blacks in election districts approved by this

court, in the totality of circumstances and

in and of itself, denies blacks equal access

to the political process. The House Dis-

tricts with particularly high black concen-

trations are District 23 (g4.gT% black), Dis-

ff,et 24 (98.43% black), District ZS (84.89%

black), District 3l (98.44% black), District

32 (98.94% black), and District g6 (97.8t%

black). Three other South Side house dis-

tricts have majority black populations.

These are District 3Z (GG.g7% black), Dis-

trict 34 (73.35% black), and District 26

(78.21% black). The four black majority

West Side house districts are District lE

(66.3Y. black), District L7 (7L.99% black),

District 18 (77.05% black), and District t9

(76.3t% black).

At the outset, we are inclined to remove

from eonsideration those districts whose

black population eonstitutes less than g0%

of the district population. Given that 65%

is a generally accepted threshold for pro

viding an opportunity for minorities to elect

a representative of their choice, it seems to

us unneeessary in light of all the circum-

stances of this case to be concerned with

districts whose black population is less

6. Inasmuch as house district 32 is an ,,interior,,

district, roughly in the center of the area of

heavy black concentration on the South Side, it

scems doubtful that, absent the most outlandish

gerr5rmandering, district 32 could be deconcen-

than 15%

"*r** threshold. In addition,

there is eyidence that in some ci;tumstanc-

es minorigr representation may be in jeop

ardy even when the portion of minorities in

a district exceeds 80%.

This leaves us with Districts ?8, ?A,25,

81, 82, and 36{istricts the black popula-

tions of which are, respectively, g4,gg%,

98.43%, U.33%, 98.44%, 98.9 4%, and g7 .gt%

of the district total. The arguably illegal

"result" of having tlrese highly coneentrat-

ed districts is not specific to any one of the

districts; indeed blacks within each concen-

trated district have an obviously strong

opportunity to elect representatives of their

choice. Instead, the adverse result may be

identifiable in terms of what might other-

wise have oecurred elsewhere. If keeping

black majorities in districts below 80% were

a primary objective of redistricting, fewer

black votes would be "wasted,'and instead

would, at least in theory, be available to

form black majority districts elsewhere.6

But this "wasting" of minority votes in

and of itself does not, we believe, in the

circumstances before us violate the Voting

Rights Act. Given the present level of

black participation in the political process

and the ability of blacks to elect rrpresent-

atives of their choice, we cannot say that

these highly concentrated districts, without

more, demonstrate a Voting Rights Act

violation. This is not to say that, in other

eircumstances in which the White a. Reges-

ter f.zctors might weigh more heavily in

favor of plaintiffs, high concentrations

could not be found illegal. We determine

only that in the case before us, and without

more, they are not illegal. But we now

confront the issue whether they may be

tinged with illegality when considered in

connection with the conespondence of dis-

trict lines to lines of raeial division (the

"tracing" issue).

We could treat the tracirig issue in either

of two ways. First, we might consider

trated. Because of our conclusions in this case,

however, we need not decide whether a differ-

enl analysis should be used for "interior,,versus

"exterior" concentrated districts.

,-, .4{,1n. -

Eon,

lnc-

ptr

tin

RyBrcKr i. srlrn BD. oF pincrroxs oF rl,I,rNors lf5gCtrG ., SZa F,trryp. f ta? (!rS,!)

whet'her voting *Yi:,r:r

?*"..poTgirF vides such minoritips with ttre reast oppor-to lines of raeial division segiregate bbcl tunity to elect representatives of theiTvoters-and whether this is uneonstitutional choice. rrr"*ir"e, under tlese circum-without regard to dilutioa of voting gtances we cannot allow the crosby plain-strength' second, we might considei tiffs to amend their complaint at this late.whether' as a matter of dilution, the con- stage to litigate these essentially unrelatedjunction of highlv concentrated brack dis- craims. see"o c. wRIGHT & A. MILLER,tricts and the tracing of racial divisions in FEDERAL PRACTICE AND pRocD

drawing district lines in some fashion re DURE S inge irrrr)sults, in terms of the Voting Rights Act, rn However, in part III B g of Rybicki I, weblacks having unequal a"""sr to ttre poiiu- carefury considerei phintiffs, argumentscal process.

regarding election district lines correspond-we think the latter approach is the only ing t" oii"rry r"""L"* housing patternscorrect one in this vote dilution case. To insofar as tiesJ fnes may contribute tothe extent the Crosby plaintiffs seek to excessive eoncentration 1o,

",.p""ting,t-"r1

?T^"ld their complaint under Fed.R.civ.p. therefore, ,,wasting;, of the ur"ci 'rot

.15o) to assert new claims- apparently aleg- Rybicki I, at LL|'Z. we found againsting unconstitutional raciar segregation aria pliintiffr,

"pprvirg

tr," city of Mobile ent*infringement of certain assocLtional rights .ia, becars" it

" "-uia"n""

did not establishof black citizens, we regard such claim-s as that the district lines were drawn with theessentially unrelated to the allegations purpose to dilute black votes. W" no\,upon which this action was premised.? reconsider the evidence to det";;;This lawsuit was pleaded, tried and decided whether, as plaintiffs allege, election dis-on a theory of dilution of, or gerrymander- trict lines trace divisior. Lt*"un Ura"t silg 9f, black voting strength. claims and whites and *hethe. this, by .,pack;;;

alleging unlawful raeial segregation by vot- and "wasting,, the black vote, violates theing district, in a fashion not encompassed "results" te-st of the amended t;ttrgwithin a eharge of gerryrmander-based vote Rights Act as applied to these circumstanc-

dilution, were not pleaded, proved or decid- es.

ed here. Compare, Wright a. Rockefeller, Our first task is to determine whether376 U.S. 52, 59, 84 S.Ct. OOS, e0O, fi and where sueh tracing takes place. TheL.Ed.2d 512 (1964) (Douglas, J., dissenting). Crosby plaintiffs ,t t"A U.o"aly in theirAlso, nothing at trial has suggestea tr*at p.op*ud findings or faet that, ,.[t]he

defendants have given their eipress or im- boundary lines for Commission llouse Dis_plied consent to resolution of iuch wholly tricts 1?, tg,28, 24, Zb,Bl, BB and 84 tracedistinct claims by this court. And we re-

main persuaaea inat any theory or segre ;1"ff?*:ffi;1",:"*A;: :1" H:Hgation by voting district-is fundamentilly lines create a ,walli a"oura the residentiallyat odds with, or is at least inconsisteni segregated black communities in Chicago,with, the idea of achieving sufficient minor- thereb'y upp"u.lrg to .onf". an official gov_ity concentrations in voting districts to en- ernmental sanction on the racial segrega-able minorities to elect representatives of tion which exis* in Chicago.,, Crosbytheir choice. This conclusion is dramatical- ptalnt;ffs, fiieisei"nirang, of Fact No.ly illustrated by the fact that voting at 97. similarryi'in lti"i, ,n".orandum supIarge (and without districts) achieves the Trting thei.- post-triai motion, the crosbyhighest possible integration of racial and plaintiffs rerered to;ir," wall, which sepa-other minorities, but simultaneousry pro rates the races by faithfuly tracking the

7' we note thal we are unaware of any decision (where race was nor an esplicitattendance crite-which has upheld a claim of t"gt.guti"" uy rion) and ..r,""1 ai.*tis. In terms of associa-,oring districr. Such a craim, *. -p..r,.,-.,

tional factors, *Jl"

"r"r.gy wourd seem dif-u'ould involve some analogy between ,iting Jir- ficulr to ;;;;,;;;; i..a ,,o, reach rhe issuetricrs and, for example, segregated scf,ools herc.

rt5,

d8-

97",

\%

gal

2t-

he

ED.

ag

eir

b€

9r-

u

ne

er

rd

b

.a

lt

e

c

f

B

a

t

t

-.J

1154

lines of segregation in housingf on the

south side of Chicago for more than 16

miles," and complained that ,,the map

adopted by the court imposes the game

racial wall as the Crcmmission's original

map, only now involving senate districts 12,

16 and 17 (as revised) and house districts

2-3, 24,31, 33 (as revised) and 86 (as re-

vised)." Memorandum in Support of

Crosby Plaintffi' Post-Trial Motion 84.8

Finally, the Crosby plaintiffs asserted that,

"eoery classification made in the creation

of this 16-mile barrier was racially found-

ed. The lines forming the wall were a

concession to the racial animosity and hos-

tility in the white areas adjoining the

wall." Reply Memorandum in Support

of Crosby Post-Trial Motion lb (emphasis

supplied).

ln Rybicki / we did not perceive a need

to establish in detail and with precision the

facts involving the alleged tracing of racial

divisions because we focused on the mo-

tives of the Commission, as required by

City of Mobile u. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 100

S.Ct. 1490, 64 L.Ed.2d 4? (1980), and found

that they had not been shown to be unlaw-

ful. Now, however, we are instructed to

look at the "results" of redistricting and

the motives of the Commission are not con-

trolling. Thus we should determine if in

faet the Commission and court-adopted

plan trace racial divisions and, if so, wheth-

er this in some fashion violates the Voting

Rights Act.

We note at the oulset that the allega-

tions of the Crosby plaintiffs quoted above

paint with too broad a brush. Instead,

E. We also note that house districts 17 and lg,

the Wesr Side districts singled our ar trial by the

Crosby plaintiffs as districts whose boundiries

traced racial divisions, were altered in our origi-

nal order in response to our finding of purpose.

ful vote dilution. District lZ is now Zl.93oZo

black and districr 18 is 77.05% black. Thus,

they are not highly concentraled, sec supra p.

1089, and further modification is clearly not

required by the Voting Rights Act, see supra p.

1089.

9. Census tract data are conlained in pl.Ex. 2g.

Plaintiffs also objected to the lines of house

dlstrict 33, as revised. Memorandum in Sup.

port of Crosbv Plainrifls post-Trial Motron 4.

This district, horvcver, is onlv 66..37%, black

67r FEDERAL SUPPLEMETIT -

great specificity is required to applaise the

, precise location of district linesl and the

populations through which they run.

Moreover, we must begin with at least a

prcliminary idea of what it means in the

redistricting context to trace racial divi-

sions.

Our analysis will focus on the popula-

tions of census tracts immediately adjacent

to district lines that follow heavily concen-

trated (85%+) black census tracts in house

districts 23, 24,31, and 36.e We have two

alternate ways of looking at the population

data in testing the tracing allegation.

First, we might find that tracing occurred

where the district line runs between a high-

Iy concentratad (85%+) black census tract

and a minimally concentrated black census

tract. Thus our focus would be on .,black,,

versus "non-black" census traets. The

second way of looking at the population

data is to find that tracing occurred where

the district line runs between a highly con-

centrated black census tract and a highly

concentrated white eensus tract (or at least

a tract containing a significant number of

whites with no substantial non-black minor-

ity). From this viewpoint a district line

drawn between a black census tract and a

tract containing substantial numbers t0 of

non-uthites (other than blacks) would not

be characterized as significantly tracing ra-

cial divisions.

We believe that the latter approach is the

correct one. If we looked more broadly at

the black versus non-black census traets,

we would not recognize the legitimate in-

and therefore the lines do not contribute to

any "packing" problem in this district. Fur-

ther, plaintiffs do not challenge the lines of

house district 32, an "interior,' district, or

house district 25, a district bordering [-ake

Michigan. Instead, plaintiffs challenge the

house districts on the westerr side of thi area

of heaw black concentration. The allegation

is that the district lines of these districts trace

the racial division between whites to the west

and blacks to the east.

10. For this purpose we have generally regarded

a minority p€rcentage of 33%.t or more as .,sub-

stantial."

er

8l

1I

n

c(

8(

w

t

8!

tr

is

A

1(

ar,

u.

t

t

e

8I

H

T,

is

H

pe

of

ru

ce

hc

74

ju

34

as

of

on

tn

ex

dn

8tr

wi

tn

tft

ia

no

12.

t

a

r

t3.

i

(

c

h€

b€

h.

3

he

ti,

B.

rt

l-

e

o

0

t

. RyBrcKr

". Silro BD. oF ELEcTroNs oF rl,I,rNors llEEr Clr. r3 37a F.srryp. I ta1 (t9t3)

terrcsts of non-black) non-white p'roups in therefore ..$rasting,, of black votes. we

avoiding the fracturing of their vbting pow- now turn to the evidence.

"I." Fot example, the district boundary House district gg ie a94% black districtalong the southeast edge of house district on Chicago,s near South Side. Dis*ict z,,s18 on tlre West Side, a 77% black district, westera boundara follows the eastern edgemns between heavily concentrated black of six cengus tacts: tracts 8402, g404,

census tracts in District 18 and tracts 8008, g40S, 6016, 6101, and 610g.12 Trart ti023006, 300?, 3008, 3003, 3002 and 2916, has a total poputation of 53lg. Of thiswhich are in house district 20. House Dis-

trict 20 isTtT,Hispanic and its composition ililf;"6rfi"",f#] *ftilirf ll!is prescribed by the Hispanic Settlement whites, Zg4 (b.B%) are blacks, and l0BA-greement. Rybicki 1, at 1123-1124 & n. e.g%) are listed as other. In addition to104. Tract 8005 has a population of 8686 and separate from the racial breakdown,and is 75.9% Hispanic. Tract 8006 is 69.g% B6 e.5%) persons are listed as persons ofHispanic. Tract 3007 is 89% Hispanic. Spanish origin.rs Tract 3i0l has a totalTract 3008 is 90.r% Hispanie. Tract Jaos popuration of t6oo, made up of 9rr (57.7%lis 46.7% Hispanic. Tract 3A02 is 88.6% *,titu.,472(Zg.g%iAsian/pacificlslanders,

Hispanic. Finally, tract 2916 is ?1.1% His- f06 (6.6%) others, and tOt (6.27,) blacks.panic. Similarly, the northeast boundary Tract Ba0i has ?Zd (L6.g%)p€rsons of Span-of house district 23, a g4% black district, ish origin. fract i4OS has a population ofruns between heavily concentrated black l?gb, with 1876 (:t7%) whites and 86T

census tracts and tracts 8402 and 8404 in (zo.s%) blacks. 79 (4.4%) people are His-

house district 19. These two tracts are panics. Tract 6016 has a population of

74% and 29.3% Asian and, we may take Et6, with 446 (g6.4%) whites, Ei (L0%) oth_judicial notice that, together with tracts ers, and 16 (8.L7.) blacks. r07 (20.7%i wr-3401 and 3403, they contain the area known sons in tract 6016 are Hispanic. Traat

as "Chinatown." Since we are not aware 6101 has a population of tZbO, with f0?zof a persuasive basis in law for fracturing (gg.z%) whites, 7s (6.1%) blacks, and 6g

one minority in the interest of deconcen- (s.5%) others . Llg (i4.5%) persons are His-trating another, we think it appropriate to panic. Finally, tract 610giasa population

examine an apparent tracing of a racial of 1g39 with i90S (gg.Z%) whites, iO 0.Sf,ldivision as presenting a suspect circum- others, S (.L%) blacks, and | (.05%) Ameri-

stance under the voting Rights Act only can Indian. tlo (l .zrqpersons are Hispan-

where a line runs between heavily concen- ic. In sum, of itre six census traets just

trated black and substantially white census beyond the western boundary of houseiis-

tracts (or at least tracts containing a signif- trict 23, tract 6108 clearly meets our crite.

icant number of whites with no substantial ria for investigation. Tlaet 6101 is at least

non-black minority), and where such a Iine suspect since he hrgest non-white group

arguably contributes to "packing" and is Hispanic and this p[oup constitutes only

ll' We would also be looking at something other Housing-Illinob Advance Rc:prt 3 (March

than "white areas adjoining the wall,,, thi situa_ lggl)), one cannot know from this data whichtion of which the Crosby plaintiffs complain of tt"ilve...i"i ."t"g;.ies(white,black,Amer-and the factual predicate foi contentions abo,rt ican Indian-EskimoAleut, Asian/pacific Island-a racial "wall." See supra p. lO9O. er, and Ott..l ff,o"la-L reduced for presenr

12. Census tracts bordering the chaltenged dis- purpos€s to reflect the Hispanic concentration

tricts can be identified by using Ct.Ex. lA, in a census tract. This does not pose a problem

which is a reproduction oith"

"o-r.t-app.orei

here, however, because for the purpose of iden-

distria lines superimposed o.,

" ".1116

t.".t tifying any tracing of racial divisions, we think

map of Cook County. that the existence of a substantial number (33%

t3- Because persons tisred in census dara as be- il.H#l:tJ:'.?ffi;:tiL[,""Tffi;t:?.jing of spanish origin may be of any race, suspect tracing of a raciai dir.ision. *e supra(Pl.Ex. 43, Bureau of the Censu-s, U.S. Depr. of n. 9 and accompanying re\r.Commerce, 1980 Census ol population- and

/

FEDERAL SUPPLEMENT1156

74.5% of. the district population. tSimilarly,

tract 6016 bears investigation since it is

only 20.1% Hiapanic- Traet 8402 is 74%

Asian and 5.3% black. Tract 3404 is n3%

Asian,r' 16.9% Hispanic, and (depending on

the race of the Hispanics) up to 6.fl. blaek.

TYact 3405 is 20.5% black with no other

substantial minority.

Hou,se district 24 is a 98% black district

immediately south and west of house dis-

trict 23. The district line under investiga-

tion here runs along the border of census

tracts 6109, 6110 and 6119. Tract 6109 has

a population of L472, with 1048 (71.1%)

whites, 302 (20.5%l blacks, \19 (8%) others,

and 3 (.2%) American Indians. 184 (12.5%)

persons are Hispanic. Tract 6110 has a

population of 1700, with 1054 (62%) blacks,

33? (19.8%) whites, 301 (17.7%) others, and

8 (.4%) Asians and Ameriean Indians. 395

(23.2%) persons are Hispanic. Tract 6119

has a population of 4791, with 1774 (37%)

whites, 1126 (36%l blacks, 1275 (26.6%\ oth'

ers, and 16 (.3%) Asians and American Indi-

ani. L999 (41.7%) persons in tract 6119 are

Hispanics. Tracts 6109 and perhaps 6110

are at least suspect under our criteria.

House district 31, the next district

whose boundary is in question, is a 98%'

black district. It is bordered by census

tracts 6119, 6118, 6117, 6705, 6?14, 6610,

?001 and part of 7005. Tract 6119, whieh

also borders district 24,has a population of

4791, with 1774 (37%) whites, 1726 (36%)

blacks, 1275 (26.6%) others, and 16 (.3%)

Asians and American Indians. 1999

(41.7% ) persons in this tract are Hispanics.

Tract 6118 has a population of 3620, with

2261 (62.4%\ whites, 772 (21.3%) others, 572

(L5.8%) blacks, and 15 (.4%) Asians and

American Indians. 1673 116.2% ) persons in

this tract are Hispanics. Tract 6117 has a

population of 3585, with 2465 (68.7%)

whites, 942 (26.2%) others, 158 (4.4%\

14. On the assumption that the 29.3o/o Asian mi-

nority is part of "Chinatown," see supra p. lO9l,

we think it is "substantial" for our Purposes

even though this minority is slightly below' the

33% "threshold" we have generall]' follou'ed.

ke supra n. 9 and accompan-)-ing text.

15. Although the data tr t hl,ic for tract 70O1 are

for the entire tract, ti)c tracl itself is divided

SUPPLEMENT "

blacks and 20 (.5%) Asians and American

r Indians. 17il (45.5% ) persons in this tract

are Hispanic. Traet 6705 has a population

ot 2254, with 2150 (95.3%l blacks, 7l (S.l%\

whites, 31 (1.3%) others, and 2 (.08%)

Asians and American Indians. 67 (2.5%)

persons in this tract are Hispanic. Traet

6714 has a population of 3006, with 2950

(98.7%\ blacks, 57 (L.6%) whites, and 5 (.1%)

Asians and others. 20 (.6%) persons in this

tract are Hispanic. Tract 6610 has a popu-

lation of 5606, with 3241 (57.8%) whites,

2029 (36.1%) blacks, 248 (4.4%) others, and

88 (1.5%) Asians and American Indians.

367 (6.5%) persons are Hispanic. Tract

7001 has a population of 3283, with 3148

(95.8%) whites, 105 (3.1%\ others, and 30

(.9%) Asians and American Indians. 150

(4.5%) persons are Hispanic.rs Tract 7005

borders both district 31 and district 36, the

next district to the south. Tract 7005 has a

population of 11,162, with 9876 (88.4%)

whites, i083 (9.7%) blacks, M0 (1.2%) oth'

ers, and 63 (.5%l Asians and American Indi-

ans. 285 (2.5%) persons are Hispanic.

To summarize district 31, traets 6119,

6118, and 6117 are each 40+% Hispanie.

Tracts 6705 and 6714 are each 90+% black.

Tlact 6610 is 57.8% white and 36.1% black.

Tlacts 7001 and 7005 clearly bear investi-

gation. Tract 6610 is at least suspect.

House district 36, a 91 .8% black district,

is the next district to south. It is bordered

by the southern half of tract 7005 and

traets 7201 and 7202. Tract 7005, detailed

above, has less than a 15% minority popula-

tion. Tract 7201, has a population of 4104,

with 3541 (86.2%) whites, 523 (12.7%)

blacks, 2l (.5%) Asians and American Indi-

ans, and 19 (.4%) others. 35 (.8%) persons

are Hispanic. Tract 7202 has a population

of 4886, with 3389 (69.3%) whites, 1412

(28.8%) blacks, 43 (.8%\ others, ald 42 (.8%)

between house districts 29 and 30. Thus only

approximately lwo-thirds of the area of 7001 is

in the district immediately adjacent to house

district 31. The heavily white ;omposition of

tract 7001, however, negates a need to more

precisely determine tt e racial percentages in the

area that is adjacent to district 31.

674

tt'

pr

lt

AI

le

8{

hi

8I

bl

71

8(

h

9l

S.

di

7.

tr

w

b

d

ll

I

d

8l

Cr

b

k

7

a

I

t.

2

d

v

6

t

I

t

t

t

I

!

t

2

t

*.,arfutr

-

i,

RYBICKI v. STAIE B'D. OF ELECIIONS OF ILLINOIS

Gltc u !l7l F8upp. ltaT (tll3)

E

I

I

!f

D

)

3

D

,)

)

I

I

Asians and American- {ndians; 80 (1.6%) 8106, s 99.6% black traqt in district 23. A

perEons are Hispanic.* [n "o.."ry, tract few of these identified traets are in dis-

?201 has legs than 15% minority pbpuhtion tricts included in the llispanic S€ttlement

end bears'investigation. Ilact 7202 is at Agreement ('r.e., tracts 6108, 6109, 6110,

least suspect.

Summary

As we review the evidence, we tltus find

several places in which district lines of

highly concentrated black districts corre'

spond to pronounced divisions between

black and white populations. F\rst, trant

7201, zn 86.U, white tract in district 28, is

adjacent to and separated by the district

line from tracts 7113 and 7303, which are

96.3% and 97.4% black tracts in district 36.

Second, tract 7005, an 88.4% white tract in

district 29, is set off from tracts 7105 and

7112, 98.4% and 97.1% black traets in dis-

tricts 31 and 36. Third., tract 7Ail, a95.8%

white traet which is primarily in district 29,

borders tract 7104, a 98.4% black tract in

district 31. Fourth, tract 6108, a 98.2%

white tract in district 21, borders tract

3702, a 97.6% black tract in distriet 23.t6

We also find several places in which the

district lines, though not conesponding to

such marked racial divisions, nevertheless

correspond to significant divisions between

blacks and whites and therefore are at

least suspect in this case. First, tract

7202, a 69.3% white tract in district 28,

adjoins tro.cts 7304 and 7306, 95.7% and

97.6% black tracts in district 36. Second,

tract 6610, a 57.8% white tract in district

29, adjoins tract 6720, a 98% black tract in

district 31. Tlhir.dl tract 6109, a ?l.L%

white tract in district 22, adjoins tracts

6122 and 3703, 97.Y, and 99.8% black

tracts in district 24. Fourth, tra.ct 6110, a

19.8% white traet in district 22, adjoins

tracts 6120 and 6121, 93.U" and 92.7%

black tracts in district 24. Fifth, tract

6101, an g$.lto whitc tract in district 21,

with 14.5% Hispanics, adjoins tra,ct 3701, z

98.3% black tract in district 23. Sixth,

tract 6016, an 86.4% white tract in district

21, with 20.7% Hispanics, adjoins lract

16. Tract 3405, which is adjacent to house dis-

trict 23, is 779i, white. lt is not included u'ithin

the tracts we have singled out, however, because

the tracl within ciistrict 23 to which it is adja-

,u57

6101 and 6016). See Rybicki d at 1123 n.

104 (quoting from Hispanic Settlement

Agreement). Any changes involving these

tracts would presumably',require the con-

sent of the DelValle plaintiffs.

Under the "results" test of the amended

Voting Rights Act, we are tentatively of

the view that over the long term, any rigid

adherence in a significant number of places

to welldefined lines of racial division be-

tween blacks and whites, in these unusual

circumstances where concentrations of

blacks exceeding 80% or 90% in voting dis-

tricts are constrained by Lake Michigan on

the east and the lines in question on the

west, may have the result of. contributing

to some degree to "packing" and vote dilu-

tion. Adherence to these lines over time,

we believe, may restrict the opp,ortunity of

blacks "to participate in the political proc-

ess and to elect representatives of tlreir

choice." There are so many variables and

factors of significance that we reach no

final conclusion on the facts before us.

But, based upon our tentative analysis, we

request that the Commission resubmit to

us alternate district boundary lines that

deviate from the pronounced division be-

tween blacks and whites in the tracts we

have identified, where highly concentrated

black districts are involved. If the new

lines include some blacks within "white"

districts while, at the same time, including

whites within "black" districts, we think

this is not per se objectionable. The pri-

mary purpose, of course, should be to move

away from using black-white boundaries as

district lines in conjunction with districts

that have very high black concentrations.

We recognize that if the addition of

whites to districts would make them less

than 80% black, this might result in the

election of representatives from the white

minority. There is evidence in the ease

cent, tract 3505, is 55% white. Thus, drawing

the district line between tracts 3405 and 3505

did not trace a significant racial tlrvis:,'rr.

\--

1158 5?4 FEDERAL SilPPLEMENT

msking such I possibili$ quite creclible.

Further, we put house district 86 in a spe-

cial category because this district has al-

ready been restructured (Ct.Ex. lA) in or-

der to provide a 66% black majority in

senate district 18. It is obviously inappro

priate to jeopardize the opportunity to elect

a black Senator in this district by shifting

the western boundary to include substan-

tially more non-blacks. Therefore, we ask

the Crcmmission to report to us regarding

what might be done about the westera

boundary of district 36 without undoing

what this court has already done and with-

out fracturing other substantial non-black

minorities.

When the Commission makes such a sub-

mission, the court will hold a further hear-

ing to evaluate its effect and to hear other

relevant evidence. Thereafter we will

make our final determinations in this case.

Of course, in making adjustments, the

Commission may make other boundary ad-

justments which may be required or desira-

ble to satisfy all other relevant criteria.

We emphasize that we are addressing

under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

the long-term results in terms of vote dilu-

tion of drawing a significant number of

district lines along arguably rigid divisions

between blacks and whites. We believe

elimination of this practice may be impor-

tant in lending better long-run flexibility to

the apportionment of election districts. We

perceive no basis, however, to respond to

this problem by adopting the "Coalition" or

"Crosby" Redistricting Maps as long as the

Commission is willing to correct the defects

we identify. As we pointed out in our

original opinion, "in view of the specific

and relatively localized defects we have

found, adopting sueh an 'outside' plan in its

entirety would inappropriately preempt the

17. Judge Grady's proposed approach is "a map 'tloc voting." If Judge Grady is'correat, the

drawn according to the traditional neutral crite- Crosby and DelValle complaints should have

ria, without regard to what I believe is the been dismissed at the outset,

constitutionally impermissible consideration of

[:ffi #::i'"".':T"jil,l"gliiffi i'JiT"LL['.T;;T;.,TS;'J:'H'ii:ix1'tr:l:

would be unintended." Rybicki /, at ll40-ll4l -"rrni.. E.g., City ol porr Arthur v. lJnited

(Grady, J., rlissenting).

-Such an-approach sim- States, _ U.S. _, lO3 S.Cr. 53O,74 L.Ed.2d

nly isnores the theory of-plainl;61t' vote dilution 334 (19g2).

claims, which are grounded in a presumption of

redistricting procedure authorized by fte

people of Illinois and the agencies emfrw-

ered by Illinois law." Rybicki I, at 1125 n.

108.

With respect to Judge Grady's separate

opinion, we think he simply misconceives

the nature of this proceeding. This case

was brought on the admittedly racrc,on-

scious theory that the opportunity to

achieve minority representation in the leg-

islature should be enhanced by redrawing

district boundaries. Under such a theory

line-drawing is necessarily a race-conscious

process. It is impossible and, we think,

unlawful, to respond to a race-conscious

claim with a color-blind remedy.rT Thus

Judge Grady's "color-blind" remedy pro

posed in his separate opinion ofJanuary 12,

1982, had been sought by none of the liti-

gants and, to our knowledge, would be

vigorously (and properly) rejected by all of

them.rt We believe that lines tracing divi-

sions between racial and ethnic groups are

properly viewed as one facet of a very

complicated problem primarily involving

the fairness of representation. With re-

spect to the use of 65 percent as a popula-

tion proportion providing a reasonable op

portunity to elect a representative of

choice, we are simply relying on a substan-

tial body of law and of policy of the Depart-

ment of Justice developed over a number of

years. See supra n. 4.

III.

Finally, with respect to the other post-tri-

al motions of the parties, we decide the

following.

The Commission's motion under Fed.R.

Civ.P. 52 for amendment of this court's

findings and conelusions contained in Ry-

bicki I is denied. For the reasons ex-

pressed

plaintifl

purpose

gument

terpreti

lied on :

do not 1

over, th

court in

dens of

rnent o.

450 U.S

(1e81),

mission

I,

with

the Crc

ters wr

note th

degree

and br

length

ment w

deny tI

argum(

standin

In a<

under r

Voting

conside

19. To

v. Bo

L.EA.'

issue,

Janua

7o Jr

S.Ct

100

104

expl

coSl

Bec

not

maJ

star

the

mer

our

this

ty,

dist

kin:

10,1

ion

\!

U the

trpow-

lC5 n.

tlrate

-ives

JCASe

rcon-

yto

: leg-

ring

leory

eious

hink,

:lous

lhus

pro-

r 12,

liti-

.be

ll of

livi-

are

'ery

'ing

re

rla-

oP

of

ln-

rt-

of

RYBICKI v. QTATE BD. OF.ELECTTONS OF ILLINOIS llSg

Ctrc u !7t Fsupp.,lta7 (t9S3)

pressed ,in that opinion, we believe that ing the absence of. purVoseful vote dilution

plaintiffs adduced'sufficient evidence of or racial gerrymandering related to the al-

purposeful discrimination at Eial; new ar- leged districting I ,,wall,', including the

gumeuts presented by the defendants, in- briefs filed by plaintiffs, defendants arf

terpreting the statistics and testimony re the amicus curiae. Insofar as purposeful

lied on for these findings of discrimination, discrimination is conceraed, we find no ba-

do not persuade us to the contrary. More- sis to amend our findings pursuant to Fed.

over, the Commission's argument that this R.Civ.p. 52O) or to hold a new trial under

court improperly refused to apply the bur- Fed.R.Civ.p. E9(aX2) and we accordingly

dens of proof formulated in Teras Depart- deny those motions.re The Crosby plain-

ment of Comrnunity Affairs a. Burdine, tiffs also request that we exercise continu-

450 U.S' 248, 101 S.Ct. 1089, 67 L.Ed.zd 207 ing jurisdiction until after the next reappor-

(1981), was fully addressed and the Com- tionment to grant future relief in t}ris case

mission's position was rejected in Rybicki under section 3(c) of the Voting Bights Act,

I. 42 U.S.C. S t9?3a(c) (19?6). Section B(c)

With respect to the various motions of states that a court "shall retain jurisdiction

the Crosby plaintiffs other than the mat- for such period as it may deem appropri-

ters we have addressed above, we first ate" in order to review changes in voting

note that these plaintiffs to a considerable qualifications, prerequisites, standards,

degree reargue matters previously argued practices or procedures. 42 U.S.C.

and briefed before us and addressed at S l9?Ba(c) (1926). We deny plaintiffs, re_

length in Rybicki L Further oral argu- quest that we retain jurisdiction until the

ment will not be helpful to us and, thus, we next reapportionment since we do not think

deny the Crosby plaintiffs'request for oral it appropriate or necessary in this case to

argument before deciding the other out- retain jurisdiction for such an extended pe-

standing motions. riod.

In addition to our analysis of the facts We ask that the Commission make a

under the ,,results,, test of the amended submission in accordance with this opinion

Voting Rights Act, we have carefully re- on or before February 7, 1983.

considered our opinion and findings regard- SO ORDERED.

19. T cl"rify our interpretation of Ciry ol Mobile of the application of the Fifteenth Amend-v. Bolden, ,146 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 64 ment in vote dilution cases, this would norL.E/.2d 47 (1980), and the fifteenth amendment aher the resuh we reach in the instant case

issue, we modify footnote 70 of our opinion of (as the crosby plaintiffs apparentry argue). ItJanuary 12, 1982 ar page 54 to read as follows:

?oJuitices stev..,s rire u.s. ar 8,Hs, roo ::r"#*lj,l1J:l1rtil'.#::fif,ij$l#

S'Ct. al 1508-1509), white (446 u.S. at lo2, pacr" standard foi a Fifteenth Amendmenr

10O S.Ct. at l5l7) and Marshall (446 U.S. ar claim, 446 U.S. ar 94, l3O_41, IOO S.Ct. ar10,+-05, 125-29, 100 S.Ct. at l5l9-20, l53l-33) 1513, 153!39; Justice Stevens, although ac-expressly stated that a vote dilurion claim is

cognizable under the Fifteenth Amendment. cepting an "objective" approach, rejected any

Becaur Justices Brennan and Blackmun did across-the-board application of the discrimi-

not articulate their view on this question, the natory impacl standard' 446 u's' at 8t-86,90,

majority vieu, is unknown. In these circum- 100 S'Ct' ar 15O9, l5ll. Bur five Justices-the

stances, we believe it is appropriate to adopl plurality Justices, 446 U.S. at 6H5, and Jus-

the plurality view of the Fifteenth Amend- tice White, 446 U.S. at 95, l0l-O3, lm S.Ct. at

menr_a vier.r. which is also consistent with 1514, l5l?_tg__+xpressly held thar the Fif.

our reading of prior appellate opinions on teenth Amendment requires proof of discrimi-

this subject. *e McMillan p. Escambia Coun- natory purpose or intent. Thus, even if we

ty, 638 F.zd 1239, 1243 n. 9 (5th Cir.), cert. were to recognize plaintiffs' claims here un-

dismbsed sub nom. City of Pensacola r,. Jen- der the Fifteenth Amendment, we would ap

kins, 453 U.S. 946, 102 S.Cr. 17, 69 L.F.d.2d ply the same srandard--dirriminatory pur-

1033 (1981). Even if Justice Brennan's opin. pos€-as we do under the Founeenth Amend-

ion can be interpreted as an implicir apnroval ment, as discussed rnfra.

R.

:ts

J-

f,-

E

,€

ri-

he

I

E

d

d

1160 6?I FEDERAL ST]PPLEMENT

t

GRADY, District Judge, dissenting in Hisp6nics' -may

also be separated from

part and concurring in part. blacks in the process' and even mixed in

rhe analysis in todav's opinion seems to f:Xf;Tf:Ji:$"iii,*m:?"[:

me to illustrate some of the difficulties .oottitotior"l considerations I b€lieve con-

inherent in any effort to draw district trolling in this case.t Aside from this fun-

boundaries along racial lines. The distinc' damentat problem, today's opinion illus-

tions made between districts on the trates the difflculty of deciding which ra-

,,white,, side of the wall which are mostly cial lines-which "tracings" al they are

white and those which are white mixed called by the majority-are tolerable and

*itt Hi.prnics and Asiatics are' I believe' which are not' I am unable to discern

,rr,rrppo"t"Ule in light of the uncontradict- what principle 11ry

through the analysis of

ed testimony that the pur?ose of drawing the majority which.could guide one 1o tle

the line this way *".'to separate whites conclusion ihat various "results" either do

from blacks. That other g"oop', such as 'or do not pass muster'2

l. I realize that the majority rejecs a constitu-

tional analysis and views the case strictly in

i..-t of thi Voting Rights Act as amended' But

i-Jo not believe Ge jmendment to the Voting

Rights Act authorizes intentional racial segrega-

tio-n. While the effect of the amendment is to

eliminate the intent requirement of the Mobile

case, ttte amendment certainly does not legiti-

*ir. tt. drawing of lines which have as their

.*pt"t'. purpose ihe separation of one race from

another. In short, the Voting Rights Act'-even

as amended, has to be read in light ol lhe

Constitution, which, in my view, absolutely pro

hibits the drawing of districl lines for the pur-

pose of racial seParation'

2. Whether the matter is viewed "as black versus

non-black," or "black versus white plus non-

whites other than blacks" (majority opinion' p'

1091), the question presented by viewing. this

case'as simpi-n.. a "paci<ing" or "dilution" problem

is, if one will excuse the expression' where,do

ro, a.r* the line? How much is enough but

-not

too much? The majority again secms to

endorse the "65 per cent formula" (see tn' 4' p'

1085, which app".tt to be the same as fn' 87 of

ifr. -.i"tiry oiition of Jan' 12, 1982' with the

.*..otitn t-hut, i, the final paragraph judicial

notiie is taken of the fact that 66 Per cenl was

,,ot gooa enough to elect a black candidate in

Senate District l8 in the March 1982 Democrat-

;i;i-..y Election). This, in terms of practical

politics, may seem good news for the Crosby

iiaintiffs; the revised map the majority.has in

rnind -ry provide even greater majo-ritie.s oi

black voters in any revised districts' I believe

ifri. *""1a be an unfortunate "victory" for the

black plaintiffs. For a recent expression conso-

,rrnl *ith my own views, see the dissenting

opinion of Justice Powell in Rogers v'-Herman-t)ise,

e$ U.S. 613, 628, ro2 S'ct' 3272' 3282'

73 L-F,d-2d lo12 (1982):

This is inherentll- a political area' where the

identification of a seeming violation does not

neccssarily suggest an enforceable judicial

i.-"alr-.. at iJasl none short of a system of

ouotas or group representation' Any such

,rsr.-, of clourse, would be antithetical to the

nrincioles of our democracY'

si" abo'Part IV of Justice Stevens' dissent in the

same case, 458 U.S. 650, 102 S'Ct' 3294'

The idea of a 65 per cent quota, guideline'-or

*h",.u.. it might be called, is as unacceptable

to -. ".

when i dissented originally, and for the

o*. .".ton.' The failure of a black to be

elected in a 65 per cent district is not' to me'

evidence thar thi percentage should be raised'

but, rather, evidence that the idea of a percent-

ir" i. ,rn*otkable in the first place' Whether

ri,., u.. comparing whites versus blacks or

Lhi,., ,...,rt blacks-, Hispanics and Asiatics' the

...rlt it the same: it just will not work' And

tt,. .ffott to make it work runs counter to the

goal of eliminating racial divisions in this coun-

trv.'I .ealize. too, that these particular plaintiffs

are not solely interested in the segregation ques-

;;. neyond that, perhaps even as much as

that, they want proportional representalion'

The majority is no more committed to proPor-

tional rlpresentation than they were at the-time

ii,. otigi*f opinions in this case were filed'

ii," .-Z"a-.nr to the Voting Rights Act makes

explicir that, whatever the "totality of circum-

stances" test may mean, it does no' lequire

"i""".tionut

representation Thus' the further

'o.ol..dine. the majority contemplates in this

I.i. *., a me ro be addressed to a vinually

i- ^ii;-*

situation as far as the voting rights

"i

Uf".tt are concerned' This is not a case like

Mobile, or Rogers v' Hertnan. ladge'- supra,

where blacks have been literally closed out ol

the political process by at-large elections in

whici they failed to elect a single repres€nta-

iir". n"tl, the difference between what the

"r",",iii.

have in the coun4rdered map and

uhar rhe) *ant is thc difference betu'een repre-

senlalion which is not quite proportional.and

reprcsenlalion uhich is strictl\ proportional ll

tht majoriN is not benl on grantirrg proPc'rlron-

,i ,.o."t"n,u,ion, tllen I fail to sct rvhr thcre is

necd [t r :, Iu:'lher hearing in thi( case'

I cout

view t]

theory

tion. I

unclear

doubt t

racial t

ing fro:

would I

tiffs tc

wittt tl

I fai

Voting

the ma

ion of ,

majorit

involvi

that a

essent

the pn

fully a

of Jan

Id(

furthe

the ev

Finall;

jurisdi

portio

the m

3. Tl

test'

not

"res

for

"les

elt,

an-

{8!E;*

,''.'.-*

. lr61BYBICKI v. ST.tTE BD. OF.ELECTIONS OF ILLINOIS

' GltG rr 3?a FAuPP' tt6t (198:!)

lm

lh

if!,

ith€

DE

tD

[us"

ra-

8De

rnd

iern

eof

tlre

:do

nrch

r the

r the

:, or

rble

'the

,be

me,

.cd,

enl-

ther

or

the

And

the

xrn-

tiffs

ues-

las

ion.

rcr-

ime

led.

&es

um-

rire

her

this

ally

frtt

tike

,ra,

:of

in

lta-

the

ud

,re-

rnd

If

on-

r is

I continue to dieagree with the majority's

view that this case* was not tried on a

O"oO of unconstitutional racial segrega-

tion. White it is true that the matter was

unclear from the pleadings, there can be no

doubt that during the trial the question of

racial Eegregation, and the stigma result-

ing from the wall, was clearly presented' I

would allow the motion of the Crosby plain-

tiffs to amend their complaint to conform

with the Proof.

I fail to see how the amendment to the

Voting Rights Act requires any change in

the map the majority approved in its opin-

ion of January 12, 1982, and as long as the

majority continues to see this case as one

involving no constitutional issue, I believe

that a further evidentiary hearing will be

essentially unproductive. The "results" of

the present map seem to me to have been

fully analyzed by the majority in its opinion

ofJanuary 12,1982, and found acceptable'3

I do agree with the majoritY that no

further argument is necessary regarding

the evidence which has already been taken'

Finally, I agree that we should not retain

jurisdiction in this case until the next reap

portionment. To that extent I concur in

the majority opinion.

Chest€r J. RYBIC4I, et al., Plaintifre'

v.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS' et

al., Defendante.

Miguel DeIYALLE, et al., Plaintiffe'

Y.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS, et

al., Defendants.

Bruce CROSBY, et al., Plaintiffe,

v.

The STATE BOARD OF ELECIIONS

OF the STATE OF ILLINOIS, et

al., Defendants.

Nos. 8l C 6030, 8l C 6052 and 8l

c 6093.

United Stat€s District Court,

N.D. Illinois, E.D.

SePt. 2?, 1983.

In suit challeqging Illinois' 1981 state

legislative redistricting plan, the District

Court, 574 F.Supp. 1082, denied Voting

Rights Act claim asserted on behalf of

black voters. Upon reconsideration, the

District Court, 574 F.Supp. 114?, requested

that the Illinois Iregislative Redistricting

Commission submit new district lines for

certain areas on Chicago's south side in

order to avoid vote dilution violative of

"results" test of amended Voting Rights

Act. Thereafter the C,ommission and plain-

tiffs worked together to reach an agree'

ment on the new lines. The District Court,

Cudahy, Circuit Judge, held that the settle

ment agreement would be incorporated into

the court-ordered redistricting plan'

circumstancs would certainly include the "re-

sults" of a redistricting, but the results are not

coterminous with the test. The test is the totali-

ty of circumstances, and it seems to me that the

majority has already exhaustively analyzed

those circumstances in its opinion of January

12, 1982. While I do not agree with that analy-

sis, my criticism is not that it was cursory'

3. The majority frequently refers to "the'results

test' of tlie amended Voting Rights Act'" I do

not read the amendment as providing for a

"results" test. The phrase used to define the lest

for determining whether a protected group has

;'less opporrunity than other members of the

electoriG to participate in the political proc-ess

and to elect iepresentatives of their choice" is

;'the totality of-circumstances." The totality of