Sims v GA Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1967

74 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sims v GA Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1967. b059e97e-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/923b9b71-6c91-4f05-bef2-76eacb4beeea/sims-v-ga-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

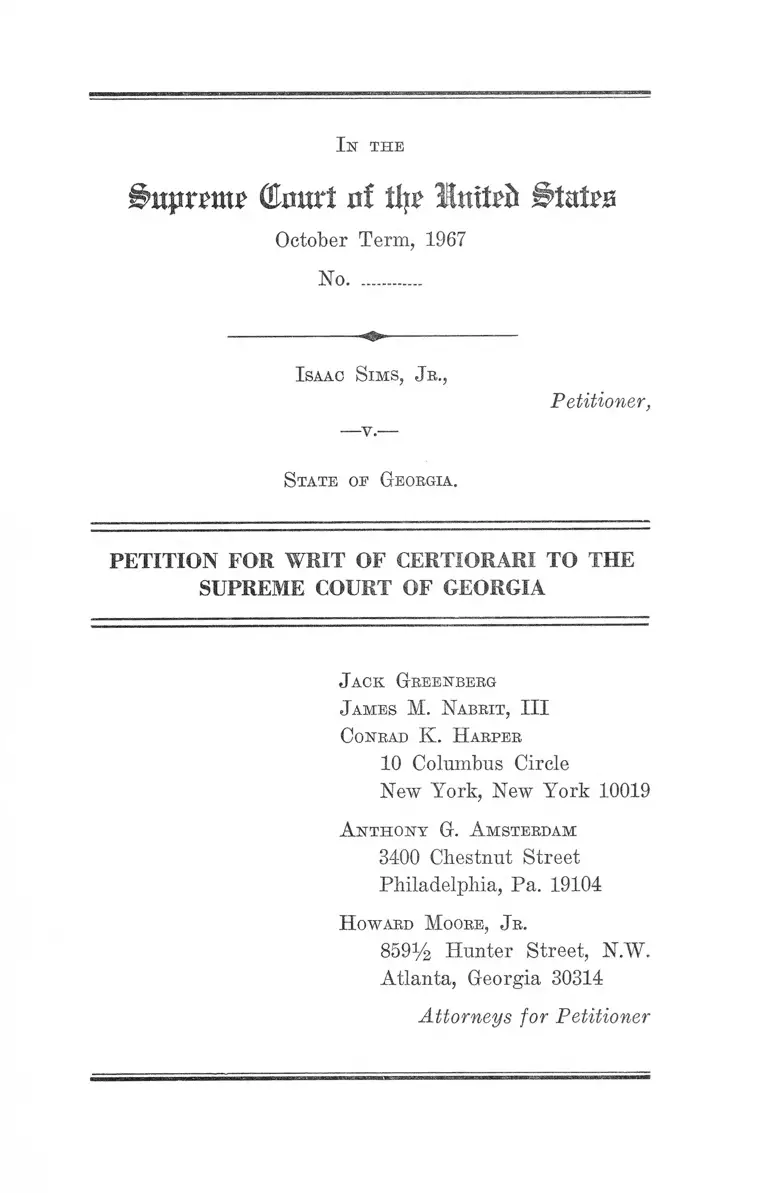

I n th e

(Emtr! of tip & M vb

October Term, 1967

No..............

Isaac Sims, Jr.,

Petitioner,

— v .—

State oe Georgia.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K. Harper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioner

I N D E X

Opinion B elow ................ 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ........ 4

Statement ............................... 5

A. Facts Regarding Petitioner’s Confession..... 8

B. Racial Discrimination in the Selection of Peti

tioner’s Grand and Traverse Juries............... 11

Reasons for Granting the Writ

PAGE

I. Petitioner’s Constitutional Rights Were Violated

by the Use at His Trial of Confessions Which

(A) Were Judged by Standards of Voluntari

ness That Were Not in Accord with Constitu

tional Requirements; (B) Were Obtained in

Inherently Coercive Circumstances Following

the Uncontested Physical Brutalization of Peti

tioner While in Police Custody; and (C) Were

Obtained in Violation of Petitioner’s Sixth

Amendment Bight to the Assistance of Counsel 14

Introduction .................................................... ......... 14

A. The Standards Applied Below to Determine

Voluntariness Were Insufficient to Satisfy

Constitutional Requirements .......................... 16

IV

Table of Cases:

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 .................................. 52

Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U. S. 773 ........................... 56

Aro Manufacturing Co. v. Convertible Top Co., 377

U. S. 476 ............................................................................ 2

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143.............................. 23

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 ....... ...............................51, 52

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 XJ. S. 199............................... 43

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U. S. 479, reversing 247

S. C. 22, 145 S. E. 2d 439 (1965) ................................ 47, 49

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F. 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1966) ....... ............ 56

Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278.................................. 22

Brubaker v. Dickson, 310 F. 2d 30 (9th Cir. 1962), cert,

den. 372 U. S. 978 ............................................................ 45

Carter v. Texas, 177 TJ. S. 442 ......... .............................. 56

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227 ................................ 23

Clewis v. Texas, 386 U. S. 707 ......... -.............................. 38

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U. S. 129...... -........................... 55

Communist Party v. Subversive Activities Control

Board, 367 U. S. 1 ........................................................ 57

Crooker v. California, 357 U. S. 433 ................................ 44

Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U. S. 568 ...................22, 37, 42

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U. S. 737 .......................22,42

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478 ...................... 3, 43, 44,46

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584 ................................. 56

Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191 ............... 3, 22, 35, 36, 38,42

Griffith v. Rhay, 282 F. 2d 711 (9th Cir. 1960), cert,

den. 364 U. S. 941 ..................................................... 44,45

PAGE

V

Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596 ............................................ 36, 37

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F.

Snpp. 156 (E. D. Va. 1964), a il’d snb nom. Tancil

v. Woolls, 379 U. S. 1 9 ................... ... ...........................50, 51

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503 ...................23, 28, 37

Hartford Life Ins. Co. v. Blincoe, 255 LT. S. 129........... 2

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 .................................. 56

Jackson v. Denno, 378 IT. S. 368 ...........................6, 7,18,47

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U. S. 719 ...........................41, 43

Johnson v. Pennsylvania, 340 IT. S. 881.......................... 37

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458 ...................................... 37

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219 .............................. 43

Malinski v. New York, 324 IT. S. 401 .............................22, 36

Massiah v. United States, 377 U. S. 201 .......................45, 46

Maxwell v. Bishop, 257 F. Supp. 710 (E. D. Ark. 1966),

denial of application for certificate of probable cause

rev’d, 385 U. S. 650 ........................................................ 48

Maxwell v. Stevens, 348 F. 2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965) ....... 48

Messinger v. Anderson, 225 U. S. 436 ........................... 2

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436 ........................—41, 42, 43

Mutual Life Insurance Co. v. Hill, 193 U. S. 551............. 2

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 .......... ........ ................... 56

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ................... 51, 56

Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U. S. 560 ...................................22, 36

Payton v. United States, 222 F. 2d 794 (D. C. Cir.

1955) ............................................................................... 39,42

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354 ........ ..... .................... 56

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 4 5 ........................................ 46

PAGE

V I

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F. 2d 34 (5th Cir.

1966) ............................-.................................................... 50

Reck v. Pate, 367 U. S. 433 ................................................ 38

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 ....................................... - 56

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534 .............................. 21, 23

Scott v. Walker, 358 F. 2d 561 (5th Cir. 1966) ............... 56

Sims v. Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7, 136 S. E. 2d 766 (1964) —.2, 55

Sims v. Georgia, 384 U. S. 998 .......................................... 2

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 537 ..... .............. —2, 7, 8,12,16,17,

18, 38,47, 54

Sims v. State, 221 Ga. 190,144 S. E. 2d 103 (1965) .......6, 20

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 ...... ................................ 56

Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315 ........................43,45,46

Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156 .................................. 40, 42

Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62 ............................... 37

United States v. Atkins, 323 F. 2d 733 (5th Cir. 1963) 50

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959) ................................................................ 56

United States v. Louisiana, 225 F. Supp. 353, aff’d 380

PAGE

U. S. 145 ......................................................................... 50

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53 (5th

Cir. 1962) ....... ..................................................... -......... 56

Wan v. United States, 266 U. S. 1 ....................-............. 22, 23

Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547 ........................................ 23

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49 ...................................... 36

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545 ........ ...... 3,7,8,11,47,48,

49, 51, 52, 53, 54

VII

page

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 .............................. 52

Wolff Packing Co. v. Court of Indus. Relations, 267

U. S. 552 ......................................................................... 2

Statutes:

23 U. S. C. §1257(3) ........................ ................................... 2

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§3-118, 3-227, 39-208 ............................ 48

Ga. Code §27-209 (1933) ............................................32,45,46

Ga. Code §27-212 (1933) .................................................. 32

Ga. Code §38-411 (1933) ........... ........................................ 4, 20

Ga. Code Ann., §59-106 (1965 Rev. Yol.) ......... ....... 4,12, 49

Ga. Code §92-6307 (1933) .... ............................................. 5,12

Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1966 Supp.) .......................... 5,48

Other Authorities:

Finkelstein, The Application of Statistical Decision

Theory to the Jury Discrimination Cases, 80 Harv.

L. Rev. 338 (1966) ...... ................................................. 53, 54

Harvard Computation Laboratory, Tables of the

Cumulative B inomial P robability D istribution

(1955) ................ ................................ .................. ........... 8a

Hoel, Introduction to Mathematical Statistics (1962) 53

In the

Hi!|iirjiitJ? Cfomrt ni % lu M BtaUa

October Term, 1967

No..............

I saac Sims, Jb.,

—v.—

State of Geobgia.

Petitioner,

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review’

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia, entered in

the above-entitled cause on June 22, 1967, rehearing of

which was denied on July 6, 1967.

Opinion Relow

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia is reported

a t ------ Ga. ------ , 156 S. E. 2d 65. It is set forth in the

appendix, infra, pp. la-5a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was

entered June 22, 1967 (IR. 285, infra, p. 6a)1 and motion

1 The certified record is in two parts: Part One (cited as IE.

) consists of proceedings in this cause following the issuance

2

for rehearing was denied July 6, 1967 (IE. 291, infra, p.

7a). On September 15, 1967, Mr. Justice Black stayed

enforcement of the sentence of death upon petitioner pend

ing the timely filing and disposition of a petition for writ

of certiorari.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U. -S. C. §1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and

asserting here deprivation of rights secured by the Con

stitution of the United States.

Questions Presented2

1. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by the admission in evidence at his capital

trial of a confession which he contends was coerced.

of this Court’s mandate in Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 538 (1967) ;

the first page of this part of the record is denominated Case No.

24152 in the Supreme Court of Georgia. Part Two (cited as

H R . ------ ) consists of earlier proceedings, including those re

viewed by this Court in Sims v. Georgia, supra; the first page of

this part of the record is denominated Case No. 22939 in the Su

preme Court of Georgia. Both parts of the record are paginated

independently with the page numbers at the lower left corner.

2 This Court granted certiorari on questions 2, 4, and 6, in Sims

v. Georgia, 384 U. S. 998, but decided the case upon another ground

without reaching any of these questions, 385 U. S. at 539. It is

well settled that this Court has certiorari jurisdiction over issues

reserved in prior disposition of a cause. Mutual Life Insurance

Co. v. Hill, 193 U. S. 551, 553-55; Hartford Life Ins. Go. v. Blincoe,

255 U. S. 129; Wolff Packing Co. v. Court of Indus. Relations,

267 U. S. 552; Aro Manufacturing Co. v. Convertible Top Co., 377

U. S. 476. See Rule 19(1) (a) of this Court, 388 U. S. 948. This

Court is not bound by the Georgia Supreme Court’s enunciation of

the law of the case doctrine (IR. 282), in refusing to rule on mat

ters previously adjudicated, because such a state law determination

does not fetter the certiorari jurisdiction. See Mr. Justice Holmes’

opinion in Messinger v. Anderson, 225 U. S. 436.

3

2. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by a conviction and sentence to death ob

tained on the basis of a confession made under inherently

coercive circumstances within the doctrine of Fikes v. Ala

bama, 352 U. S. 191.

3. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by the use of a confession obtained from him

shortly after an uncontested episode of severe physical

brutality.

4. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment right to

counsel as declared in Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478,

was violated by the use of his confession obtained during

police interrogation in the absence of counsel, or whether

petitioner’s right to counsel was effectively waived.

5. Whether petitioner has established an unrebutted prima

facie case of racial exclusion from 'Georgia juries within

the rule of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545, when:

(1) The process of jury selection from a racially desig

nated source was identical to that condemned in Whitus;

and

(2) The resulting exclusion of Negroes from jury lists

was comparable to that shown in Whitus.

6. Whether petitioner’s conviction is condemned by the

Equal Protection Clause by reason of racial exclusion from

the grand and traverse juries that indicted and convicted

him, where:

(a) local practice pursuant to state statute required

racially segregated tax books and county jurors were se

lected from such books;

4

(b) the number of Negroes chosen was only 5% of the

jurors although Negroes comprise about 20% of the county

taxpayers; and

(c) petitioner’s offer to prove a practice of arbitrary

and systematic Negro inclusion or exclusion based on jury

lists of the prior ten years was disallowed.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following Georgia statutes:

Ga. Code §38-411 (1933):

Confessions must be voluntary.—To make a confes

sion admissible, it must have been made voluntarily,

without being induced by another, by the slightest hope

of benefit or remotest fear of injury.

Ga. Code Ann. §59-106 (1965 Rev. Vol.):

Revision of jury lists. Selection of grand and traverse

jurors.—Biennially, or, if the judge of the superior

court shall direct, triennial'ly on the first Monday in

August, or within 60 days thereafter, the board of jury

commissioners shall revise the jury lists.

The jury commissioners shall select from the books

of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the per

sons so selected on tickets. They shall select from

these a sufficient number, not exceeding two-fifths of

the whole number, of the most experienced, intelligent,

and upright citizens to serve as grand jurors, whose

names they shall write upon other tickets. The entire

number first selected, including those afterwards se

lected as grand jurors, shall constitute the body of

traverse jurors for the county, to be drawn for service

as provided by law, except that when in drawing juries

a name which has already been drawn for the same

term as a grand juror shall be drawn as a traverse

juror, such name shall be returned to the box and

another drawn in its stead. (Acts 1878-79, pp. 27, 34;

1887, p. 31; 1892, p. 61; 1899, p. 44; 1953, Nov. Sess.,

pp. 284, 285; 1955, p. 247.)

Ga. Code §92-6307 (1933):

Entry on digest of names of colored persons.— The

tax receivers shall place the names of the colored tax

payers, in each militia district of the county, upon the

tax digest in alphabetical order. Names of colored and

white taxpayers shall be made out separately on the

tax digest. (Acts 1894, p. 31.)3

Statement

Petitioner, Isaac Sims, an indigent, ignorant and illiter

ate Negro, is under a sentence of death by electrocution im

posed by the Superior Court of Charlton County, Georgia,

following his conviction for the crime of raping a white

woman.

Petitioner had previously been indicted, convicted and

sentenced to death at the October 1963 Term of the Su

perior Court for the same offense. That first conviction

3 This section, applicable when petitioner was tried, was repealed

in 1966, Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1966 Supp.).

6

was set aside on habeas corpus by the Georgia Supreme

Court, which ordered a new trial, on May 7, 1964. Sims v.

Balkcom, 220 Ga. 7, 136 S. E. 2d 766 (1964). No appeal

from the first conviction had been taken by Sims’ court-

appointed counsel, the court reporter had destroyed his

trial notes, execution had been scheduled for November 13,

1963, and a commutation of sentence had been denied (II

R. 87, 95, 336, 338). One of Sims’ present counsel, Mr.

Moore, then entered the case and initiated the habeas

corpus proceedings resulting in the Sims v. Balkcom deci

sion and obtained a stay on the day before Sims’ scheduled

execution.

The indictment leading to Sims’ second conviction, re

turned October 6, 1964, charged that Sims raped Nola. Jean

Boberts on April 13, 1963, in Charlton County (HE. 20-21).

The trial commenced the next day, October 7, 1964, and a

jury returned a verdict of guilty without recommendation

of mercy on October 8,1964 (HR. 22). On appeal the Geor

gia Supreme Court affirmed the conviction, rejecting all of

Sims’ federal constitutional claims, Sims v. State, 221 Ga.

190, 144 S. E. 2d 103 (1965). This Court granted a writ of

certiorari on five constitutional questions, 384 U. S. 998

(1966).

On January 23, 1967, the Court reversed and remanded

the cause for proceedings conforming to Jackson v. Denno,

378 U. S. 368, without reaching any of the other issues

raised, 385 U. S. 538. This Court’s mandate duly issued

(IE. 6-7) and the Georgia Supreme Court, per curiam,

issued a remittitur on February 23, 1967, directing that (a)

the Superior Court hold a hearing on the single question

whether Sims’ alleged confession was vohmtary; (b) wit

nesses and other evidence might be introduced and con

7

sidered; (c) if the Superior Court found the confession

involuntary, a new trial should be ordered; (d) if the Su

perior Court found the confession voluntary, the conviction

and sentence were to be affirmed, 223 Ga. 126, 153 S. E. 2d

567 (1967) (IE, 10-11).

On March 31, 1967, the Superior Court of Charlton

County held a hearing at which no evidence was taken (IE.

250- 268). The Superior Court, at the request of counsel for

both parties, agreed to decide whether Sims’ confession was

voluntary by reviewing the printed record used in this

Court in Sims v. Georgia, supra, No. 251, October Term,

1966 (IE. 261-263).4 The Superior Court overruled Sims’

various motions for a new trial on the basis of Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U. S. 545 (1967) (IE. 256-260, 263-265).5

4 At the March 31, 1967 hearing, in support of petitioner’s posi

tion that the confession’s voluntariness was to be determined on

the basis of the printed record in Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 538,

petitioner stated that the Fourteenth Amendment required not a

de novo hearing but only a judicial finding on voluntariness (IR.

251- 252). Petitioner offered into evidence as Exhibit I, a certified

copy of this Court’s opinion in Sims v. Georgia, supra, which is

reproduced at IR. 17-23. Petitioner also offered into evidence, as

Exhibit 2, a certified copy of the transcript of record in this Court

in Sims v. Georgia, supra, which is reproduced at IR. 24-211.

Both exhibits were received in evidence (IR. 252). The hearing

was before the same judge who presided at both of petitioner’s

trials and the solicitor general represented the state at both trials

(IR. 252-253; HR. 87, 338). One of Sims’ present counsel, Mr.

Moore, represented him at the second trial (IR. 253). Petitioner

moved at the hearing that the court find the confession involuntary

on the basis of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

(IR. 265) and the court agreed to rule on that issue after studying

the record (IR. 267). The court overruled petitioner’s oral motion

that a factual finding of the confession’s involuntariness be entered

as required by the Fourteenth Amendment and Jackson v. Denno,

378 U. S. 368 (IR. 253).

5 At the March 31, 1967 hearing, petitioner moved for a new

trial on the basis of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545, on the

grounds that petitioner’s grand and traverse juries were chosen

&

On April 19, 1967, the Superior Court rendered an opin

ion, holding upon the printed record in Sims v. Georgia,

385 U. S. 538, that Sims’ confession was voluntary (IR. 227-

234). On appeal,6 the Georgia Supreme Court affirmed,

rejecting petitioner’s federal constitutional claims on the

grounds (1) that the doctrine of law of the case prevented

litigation of matters previously adjudicated and (2) there

was no error in finding the confession voluntary (IR. 282-

284). Rehearing was denied July 6, 1967 (IR. 291).

A. Facts Regarding Petitioner’s Confession

Since the Superior Court of Charlton County, in assess

ing whether petitioner’s confession was voluntary, wholly

relied upon the printed certified record before this Court

in Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 538 (IR. 261-263) and since

this Court in Sims thoroughly reviewed the applicable facts,

in a manner held unconstitutional in Whitus (IR. 256). In support

of this motion, petitioner offered in evidence the affidavit of Mr.

Harper, one of petitioner’s counsel, regarding the number of Ne

groes on the grand and traverse jury box lists from which peti

tioner’s grand and traverse juries were selected (IR. 257). The

Superior Court, considering this motion to be outside the mandates

issued in this cause, overruled the motion (IR. 260). The affidavit

was not admitted in evidence (IR. 268) but it was made a part

of the record and is reproduced at IR. 212-226. Petitioner also

moved the Court to rule on the demand for a new trial, on the

authority of Whitus, when it ruled on the confession’s voluntari

ness (IR. 263-264). The Superior Court similarly considered this

motion outside the mandates and overruled it (IR. 265).

6 Subsequent to filing a notice of appeal (IR. 3), petitioner

filed two motions in the Superior Court: (a) Motion for Rulings

on Oral Motions Made at Hearing, seeking in essence to obtain

an explicit federal constitutional ruling on the voluntariness of

petitioner’s confession (IR. 241-242) ; (b) Renewed Motion for

New Trial on the Authority of Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545

(1967) (IR. 236-238). In an order dated May 9, 1967, the Superior

Court ruled it was without authority to entertain either motion

and, therefore, made no ruling on either (IR. 245).

9

petitioner here sets out the relevant portions of this Court’s

opinion, 385 U. S. at 539-541, 543:

The record indicates that on April 13, 1963, a 29-

year-old white woman was driving home alone in her

automobile when petitioner drove up behind her in his

car, forced her off the road into a ditch, took the woman

from her car into nearby woods and forcibly raped

her. When he returned to his car, he could not start

the engine so he left the scene on foot. Some four hours

later he was apprehended by some Negro workers who

had been alerted to be on the watch for him. He told

these Negroes that he had attacked a white woman.

They then turned petitioner over to their employer

who delivered him to two state patrolmen. He was then

taken to the office of a Doctor Jackson who had previ

ously examined the victim. Petitioner’s clothing was

removed in order to test it for blood stains. Petitioner

testified that while he was in Doctor Jackson’s office

he was knocked down, kicked over the right eye and

pulled around the floor by his private parts. He was

taken to a hospital owned by Doctor Jackson, which

was adjacent to his office, where four stitches were

taken in his forehead. Thereafter the patrolmen took

petitioner to Waycross, Georgia, some 30 miles distant,

where he was placed in the county jail. During that

evening, he saw a deputy sheriff whom he had known

for some 13 years and who was on duty on the same

floor of the jail where petitioner was incarcerated. He

agreed to make a statement and was taken to an in

terview room where, in the presence of the sheriff, the

deputy sheriff and two police officers, he signed a writ

ten confession. Two days later he was arraigned.

10

Prior to trial petitioner filed a motion to suppress

the confession as being the result of coercion. A hear

ing was held before the court out of the presence of the

jury. The sheriff and the deputy testified to the cir

cumstances surrounding the taking and signing of the

confession. Petitioner testified as to the abuse he had

received while in Doctor Jackson’s office. He testified

that he “ felt pretty rough for about two or three weeks

[after the incident], more on my private than I did on

my face” and that he “ was paining a right smart.”

There was no contradictory testimony taken. The

court denied the motion to suppress without opinion

or findings and the confession was admitted into evi

dence at petitioner’s trial.

At the trial, Doctor Jackson was a witness for the

State. On cross-examination he denied that he had

knocked petitioner down while the latter was in his

office, or that he had kicked him in the forehead but

made no mention of the other abuse about which peti

tioner testified. The doctor stated that petitioner was

not abused in his presence but he refused to say

whether the patrolmen present abused petitioner as

he was not in the office at all times while the petitioner

was there with the patrolmen. In this state of the

record petitioner’s testimony in this regard was left

uncontradicted.

* * * # *

Petitioner testified that Doctor Jackson physically

abused him while he was in his office and that he was

suffering from that abuse when he made the statement,

thereby rendering such confession involuntary and the

result of coercion. The doctor admitted that he saw

petitioner on the floor of his office; that he helped him

11

disrobe and that he knew that petitioner required hos

pital treatment because of the laceration over his eye

but he denied that petitioner was actually abused in

Ms presence. He was unable to state, however, that

the state patrolmen did not commit the alleged offense

against petitioner’s person because he was not in the

room during the entire time in which the petitioner

and the patrolmen were there. In fact, the doctor was

quite evasive in his testimony and none of the officers

present during the incident were produced as wit

nesses. Petitioner’s claim of mistreatment, therefore,

went uncontradicted as to the officers and was in con

flict with the testimony of the physician.

(A more detailed statement of the facts of record relevant

to petitioner’s confession contentions is set out at pp. 24-

35 infra.)

B. Racial Discrimination in the Selection of Petitioner’s

Grand and Traverse Juries

In Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545, 548, this Court de

scribed the general Georgia procedure for selecting juries:

Georgia law requires that the six commissioners ap

pointed by the Superior Court “ select from the books

of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the per

sons so selected on tickets.” Ga. Code Ann. §59-106.

They are also directed to select from this group a

sufficient number, not exceeding two-fifths of the whole

number, of the most experienced, intelligent, and up

right citizens to serve as grand jurors, writing their

names on other tickets. The entire group, excepting

12

those selected as grand jurors, constitutes the body of

traverse jurors. The tickets on which the names of the

traverse jurors are placed are deposited in jury boxes

and entered on the minutes of the Superior Court.

Ga. Code Ann. §§59-108, 59-109. The veniremen are

drawn from the jury boxes each term of court and it

is from them that the juries are selected.

Ga. Code §92-6307, at the time of trial in this cause, pro

vided that “ Names of colored and white taxpayers shall be

made out separately on the tax digest.” Under local prac

tice in Charlton County, where petitioner was tried and

convicted, separate sections of the tax digest were main

tained for white and Negro names, the whites listed on

white paper, the Negroes on yellow paper (PR. 82; IR. 68).7

The jury commissioners, all of whom are white (PR. 83),

rely upon their personal knowledge of the persons listed

in the tax digest and their personal opinions of those per

sons’ character and intelligence, in selecting “upright and

intelligent citizens to serve as jurors.” Ga. Code Ann.

§59-106. In practice, they first examine white taxpayers’

names, then Negroes’ names. Despite a commissioner’s tes

timony that no consideration is given to race, the separate

lists make it clear whether any particular taxpayer is white

or Negro (PR. 80-81, 84, 91-92).

The 1960 United States Census for Charlton County

shows 2,656 persons over twenty-one, of whom 728 or 27.4%

are non-white (PR. 75). Petitioner offered to prove a

pattern of jury discrimination for the ten years preceding

7 Citations to PR. ------ , refer to the printed certified record in

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 538, admitted in evidence (IR. 252)

and reproduced at IR. 24-211. Owing to the accessibility of the

printed record, citations refer, where possible, only to it.

13

trial but this offer of proof was disallowed because of a

recent jury list revision (PE. 5, 8, 12, 70, 93, 95). The 1963

Tax Digest shows 1,959 taxpayers, of whom 410, or 20.4%

are Negroes (PE. 74). The record does not reveal how

many of these 1,959 taxpayers were individuals. The 1964

tax digest lists 1,553 individual taxpayers, of whom 380 or

24.4% are Negro individual taxpayers (Harper Affidavit,

IE. 213).8 Of the 147 names on the September 3, 1964,

grand jury list, from which petitioner’s grand jury was

selected, approximately 7 or 4.7% were Negroes (Harper

Affidavit, IE. 213). Of the 479 names on the September 3,

1964 traverse jury list, from which petitioner’s traverse

jury was selected, approximately 47 or 9.8% were Negroes

(Harper Affidavit, IE. 212-213). Of the panel of 99 jurors

chosen for the October, 1964 Term of the Charlton Superior

Court, from which the grand and traverse jurors were

selected in Sims’ case, approximately 9 or 9% were Negroes

(Harper Affidavit, IE. 213-214). At the trial only 5 of the

99 names were identified as Negroes (PE. 74, 89-90, 297-

298).

A comparison of the September 3, 1964 grand and trav

erse jury lists with the Colored Tax Payer section of the

1964 tax digest revealed that the names of Negroes where

they appeared on those lists, were virtually without excep

tion consecutively listed out of alphabetical order (Harper

Affidavit, IE. 214).

8 The Harper affidavit was excluded from evidence but made a

part of the record, see n. 5, supra.

14

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I.

Petitioner’ s Constitutional Rights Were Violated by

the Use at His Trial o f Confessions Which (A ) Were

Judged by Standards o f Voluntariness That Were Not

in Accord With Constitutional Requirements; (B ) Were

Obtained in Inherently Coercive Circumstances Follow

ing the Uncontested Physical Brutalization o f Petitioner

While in Police Custody; and (C ) Were Obtained in

Violation o f Petitioner’ s Sixth Amendment Right to the

Assistance o f Counsel.

Introduction

The evidence upon which Sims was convicted consisted

principally of testimony by the prosecutrix that Sims

“ forced her car off the road, dragged her into the woods,

pulled her clothes off, and raped her” (PR. 334), and that

he “kept choking her and threatened to kill her if she

screamed” (ibid.). In addition, there was testimony by the

mother of the prosecutrix and her physician, Dr. Jackson,

as to her condition after the attack, and evidence of admis

sions and confessions by the defendant.9 The circumstances

9 At petitioner’s trial the State introduced testimony concerning

an alleged oral confession by petitioner Isaac Sims to Deputy

Sheriff Jones (PR. 210), and a written confession signed by Sims

purporting to give the details of the crime (PR. 226-27). Both

the alleged oral confession (which Sims denied making) and the

signed statement were obtained April 13, 1963, while petitioner

was in custody in the Ware County Jail, as the sole suspect in a

capital felony. The prosecution also introduced testimony of a

state investigator that on the afternoon of April 15, 1963, he read

the written confession of Sims who said it was true (PR. 238).

Sims stated at trial that he did not understand what he was doing

when he signed the confession and that he was innocent of the

crime (PR. 141, 248).

15

of these admissions and confessions, which Sims contends

were involuntary and obtained by coercion, are set forth in

detail infra. The text of a written confession signed by

Sims while in custody appears at PE. 226-227. This confes

sion was written by a deputy sheriff and read to Sims, who

is unable to read or write. The first three sentences and last

three paragraphs of the statement were admittedly not

statements made by Sims but, rather, assertions of the

voluntariness of the confession written by the deputy and

read to Sims (PE. 100-101, 103-104, 218-219).

Petitioner denied understanding the import of the state

ment and denied his guilt in sworn testimony at a voir dire

hearing and in an unsworn statement before the jury (PE.

134-135, 248). Sims, in his mid-twenties at the time of

arrest, was a pulpwood worker who quit school at age

seventeen or eighteen, having completed only the third

grade (PR. 128-130). His understanding is severely limited

as is illustrated by the following testimony, which is a

mere sample of his incapacity as revealed in the record:

Mr. Moore: Do you know what is meant by “ the

statement can be used against you in court” ?

Mr. Sims: Statement can be used against me!

Mr. Moore: Statement can be used against you in

court. Do you know what that means?

Mr. Sims: No, sir.

Mr. Moore: Do you know what it means to be in

formed of your legal rights ?

Mr. Sims: Well, that’s like being good or something?

Mr. Moore: Is that what it means to you, Isaac?

Mr. Sims: Yes, sir (PR. 136).

# # * # *

16

Mr. Moore: Isaac, do you know what “ Constitu

tional rights” means?

Mr. Sims: Do you mean good or something?

Mr. Moore: Is that what it means to you, Isaac?

Mr. Sims: Yes, sir (PR. 137).

A. The Standards Applied Below to Determine Voluntariness

Were Insufficient to Satisfy Constitutional Requirements.

1. The Superior Court’s Opinion, April 19, 1967.

Following the remand in Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 538,

the Superior Court ostensibly complied with this Court’s

mandate by making an independent factual inquiry into

the voluntariness of petitioner’s confession, and duly enter

ing findings of fact and conclusions of law. Examination

of those findings and conclusions, however, compellingly

demonstrates that Isaac Sims has still not been given the

hearing on his claims of coercion required by the Consti

tution and by this Court. The Superior Court has so

persistently made findings unsupported by the record, ig

nored material evidence, and declined to resolve material

evidentiary disputes, that no inference is possible but that

the Superior Court resolved the issue of coercion by ref

erence to standards inconsistent with the law of the Four

teenth Amendment. We believe (as we shall show in the

succeeding subparts of this Petition) that application of

proper Fourteenth Amendment standards invalidates peti

tioner Sim s’ confession as a matter of law. However this

may be—whether or not a finding of voluntariness might

be made on this record consistently with proper Four

teenth Amendment standards—the failure of the Courts

below to apply such standards is alone a sufficient reason

for a second grant of certiorari and reversal of Sims’

conviction.

17

The Superior Court’s opinion is divided into three prin

cipal sections: uncontroverted facts, controverted facts,

and findings of fact. No section fairly reflects the record,

focuses on relevant issues, or addresses or resolves the

factual controversies which the Fourteenth Amendment

makes determinative. For example, in the section reciting

purportedly uncontroverted facts, the Superior Court states

that there were no threats of violence against Sims while

he was in the Ware County Jail or the interview room.

The Court makes no mention of Sims’ testimony he was

scared, that he was suffering by reason of earlier un

contested brutality, and that the Ware County officers

“ scolded” him a little while he was in the interview room.

(Compare IE. 230 with PE. 139, 143.) Similarly the Su

perior Court states Sims was not denied the use of a tele

phone. It makes no mention of the fact that Sims was not

offered the use of a telephone. (Compare IE. 230 with

PE. 222.) The Superior Court states that Deputy Sheriff

Dudley Jones wrote Sims’ statement as it was made by

Sims. Yet the record uncontradictedly shows that those

portions of the statement referring to its voluntary char

acter with Sims having been warned of his legal rights

were inserted by the officers, not spoken by Sims. (Com

pare IE. 230 with PE. 228-229.)

In the section of its opinion concerning purportedly con

troverted facts, the Superior Court erroneously asserts

that Dr. Jackson denied dragging Sims on the floor by his

private parts. (Compare IE. 232 with PE. 204-207.) As

this Court noted, Dr. Jackson did not deny or mention this

abuse in his testimony, Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. at 541.

The Superior Court also erroneously asserts that Sims

nowhere claimed that anyone other than Dr. Jackson struck

18

him (IE. 232). The record clearly shows that Sims stated

“ they,” referring to white state patrolmen in Dr. Jackson’s

office, kicked and possibly beat him (PE. 248). This Court

accurately concluded, on the same record, that, “ Petitioner’s

claim of mistreatment, therefore, went uncontradicted as

to the officers and was in conflict with the testimony of

the physician.” Sims v. Georgia, 385 U. S. at 543.

The most striking feature of the Superior Court’s “ Find

ings of Fact” is their failure to resolve evidentiary con

flicts which the Superior Court itself identified (albeit in

some matters erroneously, as we have just noted). No find

ings at all are made concerning the critical events in Dr.

Jackson’s office, and no findings are made which would

suggest the irrelevancy of those events—no findings, for

example, that the effects of the brutality practiced on Sims

in Jackson’s office were attenuated by passage of time.

Unless it be assumed that the Superior Court failed

palpably to do the job of fact-finding which Jackson v.

Denno and this Court’s mandate in Sims commanded, one

can only conclude that the Superior Court thought these

factual matters irrelevant. No clearer display of inat

tention to proper federal standards for determining the

admissibility of a confession can be conceived.

The Superior Court, in its findings of fact, does conclude

that Sims “knowingly waived” his right to have an at

torney; that Sims “knew that any statements he made

could be used against him in court” ; and “ [tjhat based upon

observation of the defendant’s demeanor while testifying

under oath, his reactions and responses to questions pro

pounded upon direct and cross-examination, it is the opin

ion of the Court that he has the mental capacity to under

stand the instructions of the officers and the nature and

19

effect of the statement he made and signed” (IR. 234).

These findings are made in the teeth of the record. Sims’

stunted mental capacity rendered him unable—even in the

safety of the courtroom—to explain words or phrases such

as “normal and ordinary” (PR. 144), “ legal rights” (PR.

136), “ constitutional rights” (PR. 137), “ freely and volun

tarily” (PR. 136), “ the right to have a lawyer” (PR. 137),

or that “ a statement can be used against you in court”

(PR. 136). Allowing all due deference to the mystique of

demeanor which the Superior Court invokes, it is simply

fanciful to find that Sims could “knowingly” waive his right

or “knew” any statement made by him could be used against

him in court. The Superior Court, it should be noted, no

where intimates that Sims was an untrustworthy witness

or was feigning the extremity of mental dullness evident

in his testimony. It is uncontested, of course, that Sims is

an illiterate, and that he quit school in the third grade

when he was seventeen or eighteen.

The Superior Court also found as facts that “ there was

no violence or threats of bodily harm, and no duress or

coercion practiced upon the defendant” (IR. 234). This

finding is wholly without foundation in the record for, as

has been said supra, Sims’ statements are uncontradicted

as to Dr. Jackson’s dragging him on the floor by his private

parts and as to violence which the state patrolmen prac

ticed on him (PR. 131, 204-207, 248).

Finally, the Superior Court found “ that at the time the

confession was made the defendant was in possession of

mental freedom to confess or deny his participation in the

crime, and that he voluntarily, knowingly and freely made

the confession in the interview room of the Ware County

Jail, in Waycross, Georgia on April 13, 1963, at 10:30

20

P.M.” (IR. 234). This finding is a penetrable conclusion,

based on nothing stronger than the partial, incomplete and

unsupported findings that precede it. We think that, in its

totality, the court’s opinion speaks for itself and estab

lishes beyond peradventure a failure to apply proper con

stitutional standards in passing on the admissibility of

Sims’ written confession.

2. The Georgia Supreme Court Opinions of

July 14, 1965, and June 22, 1967.

The Georgia Supreme Court in its July 14, 1965 opinion,

221 Ga. 190, 144 S. E. 2d 103, seems to have taken the same

narrow view as the Superior Court with regard to the ap

plicable test for voluntariness. Its opinion gives little evi

dence of an examination of the totality of the circum

stances surrounding the confession. There is, for example,

no mention of the physical brutality to which Sims was

subjected while in custody during the investigation process.

Nor is there any discussion of the many other factors such

as Sims’ mental condition, injuries, education, isolation, etc.,

which are federally pertinent. Rather, the court apparently

found it sufficient to resolve the issue that there was testi

mony that petitioner was advised of certain rights; that the

Sheriff testified “ that no threats or promise of hope or

benefit or reward were made to induce Sims to make a state

ment” (PR. 335); and that there was thus, a “ prirna facie

showing that the statement was freely and voluntarily made

and admissible in evidence. Code §38-411” (PR. 336).

Following this Court’s reversal of the decision of July 14,

1965 and the Superior Court’s rendition o f its opinion of

April 19, 1967, the Georgia Supreme Court reconsidered

the case on June 22, 1967 (IR. 285), handing down the

judgment whose review is now sought. In the June 22, 1967

21

opinion the Georgia Supreme Court reviewed in greater de

tail the circumstances which took place in Dr. Jackson’s

office but quoted in extenso from its former opinion as

to the manner in which the written confession was obtained.

The Georgia Supreme Court relied dispositively on the in

adequate findings of the Superior Court, holding: “The

trial judge, as the trier of fact, who presided at the trial

when the various witnesses testified, had the opportunity

of judging the credibility of such witnesses and it cannot be

said the decision of the trial court finding that the con

fession was voluntarily made was error for any reason

assigned” (IE.. 284).

There is no intimation here of a shift from the Georgia

Supreme Court’s earlier, artifically restrictive and federally

erroneous view of “voluntariness,” and no correction of the

insufficient consideration given the federal issue by the

Superior Court. It is therefore clear, we submit, that peti

tioner has never had a decision of the issue of voluntariness

made with reference to the appropriate constitutional stand

ards at any level—neither by the trial judge, or the state

appellate court. To give effective life to its earlier man

date and to assert the meaningfulness of the inquiry which

that mandate required, the Court should again review

this case and should reverse petitioner’s conviction on the

authority of Rogers v. Richmond, 365 II. S. 534.

In Rogers, supra, the Court invalidated a conviction rest

ing on a confession which the trial judge and the State’s

highest court had approved, since it appeared they both

“ failed to apply the standard demanded by the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment for determining the

admissibility of a confession” (365 U. S. at 540). The error

of the Connecticut courts was in determining admissibility

22

“by reference to a legal standard which took into account

the circumstance of probable truth or falsity” (365 U. S.

at 543).

In Isaac Sims’ case, it is apparent that the courts below

made a similar error. Ignoring facts and circumstances

plainly pertinent under federal standards, and narrowly

concentrating on the immediate scene of the confession, to

the exclusion of vital earlier events that affected Sims’ will

to make it, the Superior and Supreme Courts appraised

the case in terms of only the most obvious and obtrusive,

immediately contemporaneous, external coercive influences.

They restricted their attention to the sorts of blatant duress

made relevant by the Georgia statutory standard for the ad

missibility of confessions—threats and promises—and thus

ignored a multitude of the more subtle factors which this

Court has recognized as pertinent to the inquiry whether

a confession is in fact, as the Fourteenth Amendment re

quires, a free and uncompelled act: the accused’s mental

feebleness, Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U. S. 568; lack of

education, Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191; fears bred of

race, Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U. S. 560; the stripping of the

accused, Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401; physical bru

tality, Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278; failure to warn

the accused of his rights to silence and to appointed counsel,

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U. S. 737.

Furthermore this Court long ago condemned as unduly

restrictive a review of confessions that was limited to deter

mining whether they were induced by immediate duress, in

such forms as promises or threats. Mr. Justice Brandeis

wrote in Wan v. United States, 266 U. S. 1,14-15:

23

The court of appeals appears to have held the prison

er’s statements admissible on the ground that a con

fession made by one competent to act is to be deemed

voluntary, as a matter of law, if' it was not induced by

a promise or a threat; and that here there was evi

dence sufficient to justify a finding of fact that these

statements were not so induced. In the Federal courts,

the requisite of voluntariness is not satisfied by estab

lishing merely that the confession was not induced by

a promise or a threat. A confession is voluntary in

law if, and only if, it was, in fact, voluntarily made.

A confession may have been given voluntarily, al

though it was made to police officers, while in custody,

and in answer to an examination conducted by them.

But a confession obtained by compulsion must be ex

cluded, whatever may have been the character of the

compulsion, and whether the compulsion was applied

in a judicial proceeding or otherwise. Bram v. United

States, 168 U. S. 532.

At least since Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 239, the

rule of Wan has been the law of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. See also Ward v. Texas, 316 U. S. 547, 555; Ashcraft

v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143, 154. Petitioner has thus not

had a determination of voluntariness in the courts below

which is consistent with constitutional standards. Rogers

v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534; Wan v. United States, 266

U. S. 1; cf. Haynes v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503, 516-517,

note 11. The Court should granted certiorari so to declare.

24

B. Petitioner’s Confession Was Obtained in Inherently

Coercive Circumstances and After He Had Been Phys

ically Brutalized While in Custody, and Its Use to

Convict Him Violates the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

1. Facts and Circumstances Surrounding the Confession.

Isaac Sims was taken into custody by Sgt. George Sims

and Trooper Peacock of the State Patrol at about 3 :00 p.m.

on April 13, 1963 (PE. 184-185). On orders from Sheriff

Sikes, petitioner was taken by Sgt. Sims to the medical

office of Dr. Joseph M. Jackson (PE. 185). He was taken

directly to Dr. Jackson’s office from the place where the

police took him in custody (PE. 184-185). It is clear that

the officers took Sims to Dr. Jackson’s office as a part of

their investigative process, so that his clothes might be

removed and examined for evidence of the crime (PE.

205, 206-207).

Petitioner Sims testified very clearly that he was bru

talized while in custody at Dr. Jackson’s office. He gave

such testimony both in the pre-trial hearing outside the

presence of the jury (PE. 131), and in his unsworn state

ment, before the jury (PE. 248). Sims stated that he was

in Dr. Jackson’s office with seven or eight white state

patrolmen. When asked what happened to him there, Sims

said (PE. 131):

Well, Dr. Jackson, he knocked me down and kicked

me over my eye lid and busted my eye on the right

side.

Q. Did anything else happen to you! A. And he

grabbed me by my private and drug me on the floor.

Sims’ statement before the jury was to the same effect

(PE. 248):

25

Well, they brought me over to Dr. Jackson’s office

and they carried me in there, about six or seven State

Patrols, and Dr. Jackson beat me, and taken my clothes

off, and then carried me over to the bigger hospital

and stitched my eye up where they kicked me over the

eye, and put me on some white clothes—white pants,

but I kept my shirt I had on.

Q. While you were in Dr. Jackson’s office did he

drag you around the floor ? A. Yes, sir.

=£ # # # #

Q. (By the Defendant’s Attorney) What happened

to you while you were in Dr. Jackson’s office? A.

Well, he pulled me by the privates.

When Sims testified in the pre-trial hearing he was

cross-examined, but the prosecutor never ashed Sims a

single question about what happened to him in Dr. Jack-

son’s office (PR. 137-143). In addition, the prosecutor put

on no testimony at all to rebut Sims’ claim that he was

beaten, kicked over the eye, and pulled by his private

parts in the presence of six to eight officers.

The prosecutor never ashed any witness a single ques

tion about what happened in Dr. Jackson’s office. Sgt.

George Sims, the officer who took petitioner to and from

Dr. Jackson’s office (PR. 185), was never asked what hap

pened in the office.10 The other officers who were present

were never called to testify or identified by name.11 The

prosecutor did not ask Dr. Jackson a single question (on

10 Dr. Jackson said that he presumed that the officers in the office

with Sims were the ones who brought him there (PR. 202).

11 The exception was Trooper Peacock who was mentioned by Sgt.

Sims (PR. 184) but did not testify.

26

direct or re-direct) about what happened while Sims was

in his office (PR. 189-197, 208).

Defense counsel did cross-examine Dr. Jackson about

the events in his office (PR. 202-207). Certain aspects of

Sims’ testimony were confirmed by Dr. Jackson, who said:

(a) that Sims was brought to his office (PR. 202);

(b) that police officers and troopers were there and he

was not alone with the defendant (PR. 202);

(c) that Sims’ clothes were removed (PR. 202);

(d) that he (Dr. Jackson) “assisted him slightly” and

gave him “ a little help” in removing his clothes, including

his pants and his underpants (PR. 202-203, 206-207);

(e) that Sims was down on the floor while in the office

(PR. 203, 204);

(f) that by the time Sims left the office he “had a place

over his eye that required .some treatment” (PR. 204) ;12

(g) that when Sims left “he was taken over to the

hospital and the place was treated that I told you about”

(PR. 207);

(h) that at the hospital Dr. Aztui put four stitches in the

injury over Sims’ eye (PR. 207).

Dr. Jackson’s explanation of what happened to peti

tioner in his office was highly evasive and partly in the

form of denials of knowledge about what happened to

Sims. Asked whether the State Patrolman “put the place

12 A state investigator observed the injury on his face two days

later (PR. 242).

27

over Ms eye,” Jackson answered, “ I don’t know who put

it there” (PR. 204). When asked if the officers were heating

Sims he said:

A. You’ll have to ask the officers.

Q. I ’m asking you, Dr. Jackson. I ’m asking you

whether or not the officers were beating the defendant.

A. I will say that I wasn’t there all the time (PR. 204).

Referring to the “place” over Sims’ eye, Jackson was

asked:

Q. He didn’t have it over his eye when he came

into your office, did he? A. I didn’t see him till after

he got in.

Q. And when you first saw him in your office he

didn’t have it? A. I couldn’t see it. He was sort of

slumped over, sort of falling around, like. Most any

thing could have happened to him (PR. 204).

Dr. Jackson denied that he knocked Sims down (PR.

204) or that he kicked him (PR. 205). But when asked

whether Sims was kicked he said only: “ I don’t know

that he was” (PR. 205). Earlier, Dr. Jackson was asked

whether Sims was knocked down and he said: “ I don’t

know whether he was knocked down or fell down” (PR.

203).

Dr. Jackson was asked:

Q. Did you find him down on the floor? A. He

sort of fell in the floor.

Q. He just sort of fell? Where were you standing

at the time he sort of fell? A. I was standing on my

feet.

Q. Were you standing near him? A. Fairly close.

28

Q. Were you standing as close as I am to you, or

closer? A. Probably a little closer.

Q. Where you could touch him? A. I think he could

touch me.

Q. And you could touch him? Right? A. Yes (PR.

204).

Thus, Dr. Jackson’s testimony was that Sims was close

enough to touch him when he fell on the floor, but Dr.

Jackson did not know “ whether he was knocked down or

fell down” (PR. 203). Later Jackson said Sims was on the

floor when he entered the room (PR. 205). In Jackson’s

own words, “ Most anything could have happened to him”

(PR. 204). Despite all this, throughout the entire trial the

prosecutor avoided any inquiry into what happened to

Sims in Dr. Jackson’s office. Although Dr. Jackson denied

on cross that he knocked Sims down or kicked him, the

prosecution asked no questions about this and called none

of the policemen to corroborate the doctor’s denial. Plainly

Sims was injured while in custody. There was no sug

gestion that he resisted arrest or anything of that nature.

Moreover, the doctor gave no testimony denying Sims’

claim that he was pulled by his private parts and dragged

on the floor. There was no rebuttal or denial of this

testimony at all and it stands uncontradicted and uncon

tested in the record. The language of the Court in Haynes

v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503, is pertinent in appraising

the State’s failure to rebut Sims’ claim of brutality:

We cannot but attribute significance to the failure of

the State, after listening to the petitioner’s direct

and explicit testimony, to attempt to contradict that

crucial evidence; this testimonial void is the more

29

meaningful in light of the availability and willing

cooperation of the policemen who, if honestly able

to do so, could have readily denied the defendant’s

claims. (373 IJ. S. at 510.)

In addition to the evidence of physical brutality, there

are, of course, a variety of other facts to be considered in

appraising the totality of circumstances surrounding the

confessions. They reveal that Sims was bewildered, help

less, alone, hungry, in pain and in fear when he signed

his written statement.

Isaac Sims is an indigent, ignorant, illiterate Negro, who

cannot read and can write only his name (PR. 130). He has

spent most of his life in Charlton County in the southeast

part of Georgia (PR. 129). Both of his parents are dead;

his closest relatives in Charlton County were two sisters

(PR. 128). At the time of his arrest he was in his twenties;

the record leaves his exact age unclear.13 Sims was unable

to tell what year he was born (PR. 128). He went to the

third grade in school, quitting when he was “ seventeen or

eighteen” (PR. 130). He testified, “Well, I didn’t go [to

school] too much on account of I had to help my father

work, and he taken me out of school” (PR, 129). He worked

as a pulpwood worker, earning forty to sixty dollars a week.

He is indigent, had appointed counsel at his first trial, and

has proceeded in forma pauperis throughout the case.

The record reveals his limited mental capacity in many

instances. He did not know the year he was born; nor could

13 The confession stated that he was 27 on the day of arrest in

April 1963 (PR. 226) ; he testified that he was 29 at the trial in

October 1964 (PR. 247), but his birthdate was February 5 (PR.

128).

30

he state when his father died (PE. 128). He was totally un

able to explain words and phrases such as “normal and

ordinary” (PR. 144), “ legal rights” (PR. 136), “ constitu

tional rights” (PR. 137), “ freely and voluntarily” (PR.

136), “ the right to have a lawyer” (PR. 137), or that “ a

statement can be used against you in court” (PR. 136).

Sims “ stutters” when he speaks (PR. 122).

Sims was a Negro charged with the rape of a white

woman—a capital felony in Georgia. The prosecutrix was

the unmarried daughter of the local postmaster (PR. 61).

At about 2 :00 or 2 :30 p.m. Sims was taken into custody and

held at gunpoint some five miles from the scene of the

crime by two Negro men who had been ordered by their

boss, a local white man, to look for any “ stray man” (PR.

169, 175-176). He was then taken by this white man, Noah

Stokes, accompanied by several other men, to state troopers

who carried him to Hr. Jackson’s office where Sims was

brutalized as we have described above. After Sims was

treated at the hospital for his eye injury, the police took

him to the Ware County Jail in Waycross, some thirty or

thirty-five miles away from Folkston and located outside

the county where the crime occurred, for “ safe keeping”

(PR. 233-234, 242).

The police testimony is that at about 6 :30 p.m., while con

fined in a cell at the Ware County Jail, Sims orally admitted

“ raping” or “molesting” a white woman in Folkston in a

conversation with Deputy Sheriff Dudley Jones whom Sims

had known for more than a dozen years previously14 (PR.

113, 209-210, 214-216). Jones did not testify that he gave

Sims any warnings prior to eliciting this admission, either

14 Sims denied making this oral confession (PR. 134, 138-139).

31

as to Sims’ right to remain silent, that his statement would

be used against him, or as to his right to counsel. Jones

testified that Sims then agreed when asked if he wanted

to make a statement to the sheriff ( Pit. 113, 210).15

Sims remained alone in a cell until about 10:00 or 10:30

that evening when he was taken to the “ interview room”

in the jail (PE. 210, 223). Sims had not been fed since he

was taken into custody some 8 hours earlier and he was

still in pain from the injury sustained in Dr. Jackson’s

office.16 There were four white officers in the “interview

room” with Sims: they were the Sheriff and Deputy Sheriff

of Ware County, the Chief of Police, and the Constable.17

Sims testified that he was “ scared” (PE. 143). As to his

treatment, he said, “ they didn’t beat me, but they kind of

scolded me a little” (PE. 139). None of Sims’ testimony

in these regards was rebutted.

Since his arrest, petitioner had not been in touch with

any relative, friend or attorney. He had not been offered

the use of a phone (PE. 222) and he had not been taken be

fore a magistrate in accordance with Georgia law (PE. 235-

15 Sims also denied this (PR. 133).

16 Sims testified at PR 135-136:

A. Well, I felt pretty rough for about two or three weeks,

more on my private than I did on my face.

Q. When you said you felt pretty rough, what did you mean,

Isaac ? A. Well, I was paining a right smart.

Q. Were you paining a right smart when you were in the

room with Sheriff Lee and Deputy Sheriff Jones? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, after you were taken into custody up until the time

you were taken upstairs had you been given anything to eat?

A. No, sir.

Q. Were you hungry? A. Yes, sir; I could have eat.

17 The Police Chief and Constable were not called as witnesses.

32

236).18 He was in jail in the adjoining county some 30 or

35 miles from Folkston (PR. 67, 242).

The record does not make it clear how long Sims was in

the interview room before the confession was given and

signed,19 or to what extent, if any, Sims was interrogated.

18 Georgia law specifically required bringing petitioner promptly

before a magistrate where, as here, the arrest was made without a

warrant:

“Duty of person arresting without warrant.— In every case

of an arrest without a warrant the person arresting shall with

out delay convey the offender before the most convenient officer

authorized to receive an affidavit and issue a warrant. No such

imprisonment shall be legal beyond a reasonable time allowed

for this purpose and any person who is not conveyed before

such officer within 48 hours shall be released.” Ga. Code

§27-212 (1933).

Even if the arresting officers had a warrant, they were similarly

obligated:

“ Officer may make arrest in any county. Duty to carry pris

oner to county in which offense committed.—An arresting offi

cer may arrest any person charged with crime, under a war

rant issued by a judicial officer, in any county, without regard

to the residence of said arresting officer; and it is his duty to

carry the accused, with the warrant under which he was ar

rested, to the county in which the offense is alleged to have

been committed, for examination before any judicial officer of

that county.

“The county where the alleged offense is committed shall pay

the expenses of the arresting officer in carrying the prisoner to

that county; and the officer may hold or imprison the defen

dant long enough to enable him to get ready to carry the

prisoner off. (Acts 1865-6, pp. 38, 39; 1895, p. 34.)” Ga. Code

§27-209 (1933).

19 Sheriff Lee testified (PR. 104) :

Q. Do you know what time on the evening of April 13, 1963,

that you started taking this statement? A. Well, the state

ment was short. It wouldn’t have taken but just a few minutes.

Q, How many minutes? A. Oh, ten or fifteen minutes.

Q. Did you start taking the statement at 10:30 or did you

33

When asked whether he questioned Sims, Sheriff Lee said,

“ I don’t think so,” then, “ I could have,” and finally, “ I just

don’t recall right now” (PR. 105). Sims said he was ques

tioned by Lee (PR. 135,140), and also that he was “ scolded”

(PR. 139).

Deputy Sheriff Jones wrote out the confession and read

it to Sims. He admittedly wrote out some matter which

Sims did not say. The Sheriff, and his deputy who actually

wrote the confession, testified petitioner did not say that

the statement had been made freely and voluntarily or that

he had been informed of his legal rights, although the writ

ten statement includes those words. In fact, petitioner does

not even know the meaning of “ freely and voluntarily”

(PR. 136). Every word in the confession asserting its volun

tariness and its having been made with knowledge of the

legal consequences was inserted not by petitioner but by

his inquisitors. The deputy sheriff crossed out several

words in the original statement, including the words, “ I

have read” when it was learned the petitioner could not

read (PR. 229).

The sheriff testified that he told petitioner that before

he made a statement he was entitled to an attorney and

conclude it at 10:30? A. Well, I wouldn’t say we finished at

10:30 or started at 10:30. It was approximately 10.

Q. So you questioned him from 10 to 10:30! A. How is

that?

Q. You questioned him from 10 to 10:30? A. I didn’t say

that.

Q. You started at 10? A. I didn’t say that.

Q. You started at 10:30, then? A. I said that we could

have finished at 10 :30 or started at 10 :30. I don’t recall.

Deputy Sheriff Jones said that Sims was brought down at 10:30

(PR. 113); that it took him approximately twenty to thirty minutes

to write down Sims’ statement (PR. 119), and five or six minutes to

read it to him (PR. 121-122).

34

that petitioner said he did not want one (PR. 99-100, 224).

The sheriff also said that he told petitioner “ that the state

ment he was going to give could be used against him in

court” (PR. 99-100, 225). On each of the occasions at trial

when Sheriff Lee recounted his warning to Sims, he failed

to mention that he advised Sims of his right to remain

silent (PR. 99-100, 224-225). However, a sentence at the

end of the confession written by the deputy recites: “ I have

been informed of my legal rights by Sheriff Robert E. Lee

that I did not have to make any statement whatsoever,

knowing that this statement can be used against me in a

court of law” (PR. 227). No one offered Sims the use of a

phone or advised him that a lawyer would be appointed if

he could not afford one.

On Monday afternoon, April 15, 1963, Agent F. F. Cor

nelius of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation brought Sims

in handcuffs from the jail in Waycross back to the sheriff’s

office in Folkston (PR. 237, 241). Cornelius questioned Sims

in the sheriff’s office in the presence of five other police of-

cers20 (PR. 239-240). Cornelius read the statement Sims had

signed on Saturday night to Sims, asked him if it was true,

and Sims said, “Yes, sir” (PR. 238). Cornelius did not cau

tion Sims that he was not required to answer and could

remain silent, or otherwise advise him of his rights (PR.

241). Sims apparently still had no attorney and had not

seen any friends or relatives during the period since his

arrest (PR. 241-242). He was first taken before a magis

trate on April 15th (PR. 66). The record is silent on

whether the questioning by Cornelius came before or after

that proceeding. But a warrant charging Sims with the

20 None of these five officers testified at the trial.

35

crime had been issued at some time before he was brought

back to Folkston and made the admissions to Cornelius

(PR. 239).

2. The Confessions Were Obtained in Inherently Coercive

Circumstances; Their Use Violated the Due Process

Clause; and the Decision to the Contrary by the Courts

Below Warrants Review Here by Reason of Its Incon

sistency With Pertinent Decisions of This Court.

The Court has consistently held that the voluntariness

of a confession must be determined in the context of all

the surrounding circumstances as they appear from the

Court’s independent examination of the uncontested facts

on the entire record. Examination of the record in this

case makes it plain that each of the confessions allegedly

given by Sims to the law authorities while he was in cus

tody were given in inherently coercive circumstances and

were not voluntary.

The recitation of the facts above demonstrates that Fikes

v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191, should have compelled the

Georgia courts to exclude Sims’ confessions. The similari

ties between this case and Fikes are numerous and signifi

cant. In both cases the petitioner was a Negro in his

mid-twenties charged with a sexual assault upon the daugh

ter of a local public official in a southern community. Both

Fikes and Sims had attained only third grade educations

when they quit school in their late teens. Sims, like Fikes,

is of limited mentality. In this case, as in Fikes, the peti

tioner was first arrested by civilians; was not arraigned or

taken before a magistrate prior to his confession; was

carried to a jail far from the scene of the crime; and was

allegedly advised of some of his legal rights by a law

36

enforcement officer before confessing. Sims saw no friend,

relative or counsel; Fikes saw his employer, but his father

and a lawyer were denied access to him. The Fikes record

contained “ no evidence of physical brutality” (352 U. S. at

197). But Isaac Sims made a strong and largely uncon

tested showing that he was brutalized and suffered injury

requiring medical treatment, while in the custody of officers

who were engaged in an investigative process.

The Fikes case involved a longer period of custody and

questioning before the confession, viz., five days in Fikes

as against 7 or 8 hours in this case. But even a short period

of time may be sufficient to overpower a suspect’s will

(Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596), and the denial of food to

petitioner during his confinement bears directly upon the

confession’s alleged voluntariness ( Walts v. Indiana, 338

U. S. 49, 53; Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U. S. 560, 567), as does

the stripping of petitioner in Dr. Jackson’s office (.Malinski

v. New York, 324 U. S. 401). The physical beating suffered

by Sims is sufficient to counterbalance the comparatively

short period of questioning revealed by the record. As Mr.

Justice Frankfurter (joined by Mr. Justice Brennan) said

concurring in Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191, 198:

It is, I assume, common ground that if this record had

disclosed an admission by the police of one truncheon

blow on the head of petitioner a confession following

such a blow would be inadmissible because of the Due

Process Clause.

Sims has more than met the requirement that he show

“ one blow.” It is not disputed that while engaged in their

investigation the police took Sims to Dr. Jackson’s office

where he sustained injuries requiring medical treatment

37

(four stitches over the eye), which he claimed were received

from blows and kicks in the presence of the police, an

episode the prosecution has never troubled to deny or re

but. We submit that it is plain that the prosecutor never

asked a question or put on a witness to deny Sims’ version

of this incident because he could not honestly do so (cf.

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503, 510).

The element of violence in this case makes it as strong,

if not stronger than Fikes, swpra, and similar cases where

the Court has viewed the circumstances as sufficiently coer

cive to strike down convictions. See, particularly, Haynes

v. Washington, 373 IT. S. 503; Culombe v. Connecticut, 367

U. S. 568; Turner v. Pennsylvania, 338 U. S. 62; Johnson v.

Pennsylvania, 340 U. S. 881 {per curiam; facts stated in

Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U. S. 568, 628).

And, of course, the fact that Sims’ signed statement con

tains assertions of voluntariness, composed by the police,

does not suffice to save the confession in view of the other

circumstances. A strikingly similar recital also dictated

by the police was disregarded by the Court in striking down

the conviction in Haley v. Ohio, 332 U. S. 596, 598, 601.

Sims’ testimony indicates he did not even comprehend the

meaning of the recitals of voluntariness or understand the

significance of the warnings he was given. His supposed

waiver of the right to counsel could not, given his lack of

understanding and inability to understand common legal

terms expressed in ordinary language, be regarded as “ an

intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known

right or privilege,” Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U. S. 458, 464.

Plainly, petitioner did not know a lawyer’s function or

understand how a lawyer could be of assistance to him.

38

Here, as in Fikes, “ The totality of the circumstances that

preceded the confessions . . . goes beyond the allowable

limits” (352 U. S. at 197). The conclusion applies equally

to the alleged oral admission to Deputy Jones, the signed