Correspondence from Wallace to Clerk; Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Motion for Permanent Relief

Public Court Documents

November 6, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Wallace to Clerk; Defendants' Response to Plaintiffs' Motion for Permanent Relief, 1985. eb2094c1-dd92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9309c2fe-7866-4ee9-8e23-d020e0ce7729/correspondence-from-wallace-to-clerk-defendants-response-to-plaintiffs-motion-for-permanent-relief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

x

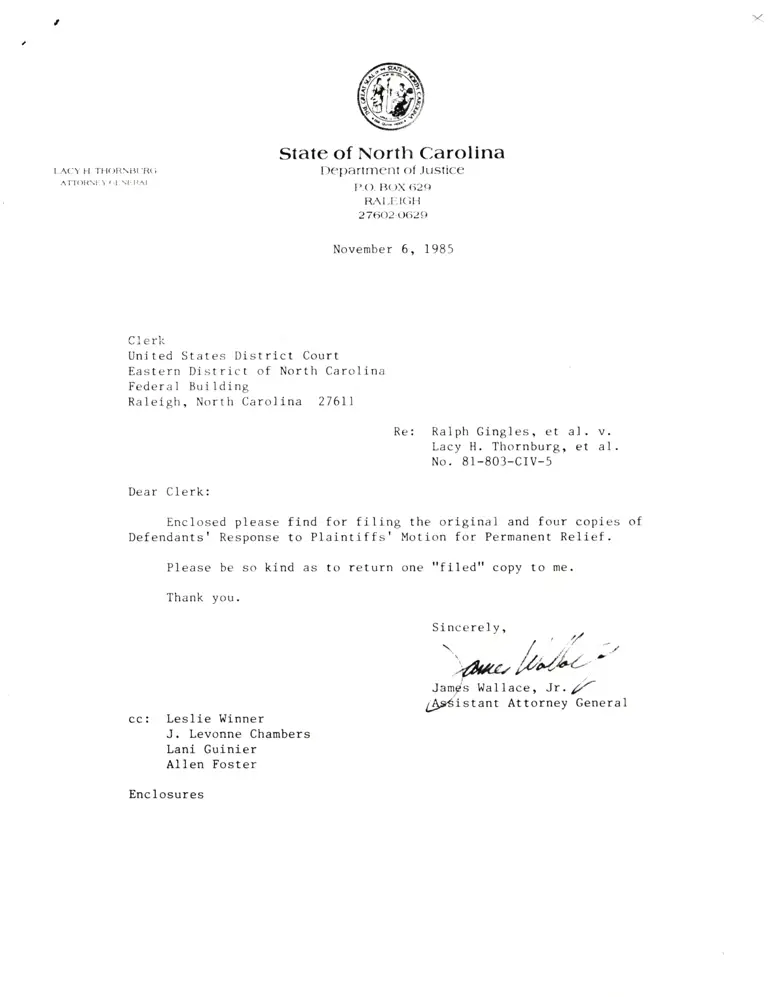

LACY H. THORNBUR(I

ATTORNFT \' ('t-t Nt-t ll.Al -

State of North Carollna

Department of Justice

' P.o. Rox 62s

RAI-EIGH

27@.2-{J629

November 6, 1985

Cl erk

United States Distrlct,Court

Eastern District of North Carollna

Federal Building

Ralelgh, North Carollna 27611

Re: Ralph Glngles, et al. v.

Lacy H. Thornburg, et al.

No. 81-803-CIV-5

Dear Clerk:

Enclosed please flnd for fillng the orlglnal and four copies of

Defendantsr Response to Plalntiffs' Motlon for Permanent Relief.

Please be so kind as to return one ttflledtt copy to me.

Thank you.

cc: Leslle Wlnner l

J. Levonne Chanbere

Lanl Gulnier

Allen Foeter

Enclosures

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OT NORTH CAROLINA

RALEIGH DIVISION

N0.81-803-CrV-5

MLPH GINGLES, et aI.,

Plalntiffs,

v.

LACY H. THORNBURG, Attorney

General , et al. ,

DEFENDANTSI RESPONSE TO

PI"AINTIFFS I MOTION FOR

PERHANENT RELIEF

Defendants.

Now come Defendants ln the above-captioned actlon and advlse the

Court thatr ln light of this Courtrs original Order and Memorandum

Opinion of.27 January,1984, they lntend to file no resPonse In

opposltion to Plalntiffs' Motlon for Permanent Rellef' flled in the

Court on or about 21 0ctober, 1985.

This the day of November, 1985.

I^ACY H. THORNBURG

Post Offlce Box 529

Ralelgh, North Carollna 27602

(919) 733-72L8

6

CERTIFICATE OT SERVICE

I certlfy that I haye served the foregolng DEFENDANTST RESPONSE T0

PLAINTIFFST MOTIoN FOR PERIIANENT RELIEF on all partles by placlng a copy

thereof enclosed tn a pobtage prepatd properly addressed wrapper ln a

post offlce or offlce depository under the excluslve care and cuetody

of the Unlted States Posrtal Servlce, addressed to:

Ms. Leslle J. I{lnner

Ferguson, Stelir, Watt, Wallas &

Adklns, P.A.

Sulte 730, East Independence Plaza

951 South Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carollna 28202

Mr. J. l,evonne Chanbers

l'{s. Lan[" Gulner

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Mr. C. Allen Foster

Foster, Conner, Robeon & Gumbiner, P.A.

104 North Elm Street

Greensboro, North Carolina 27401

Thls the Q- Oq of November, 1985.