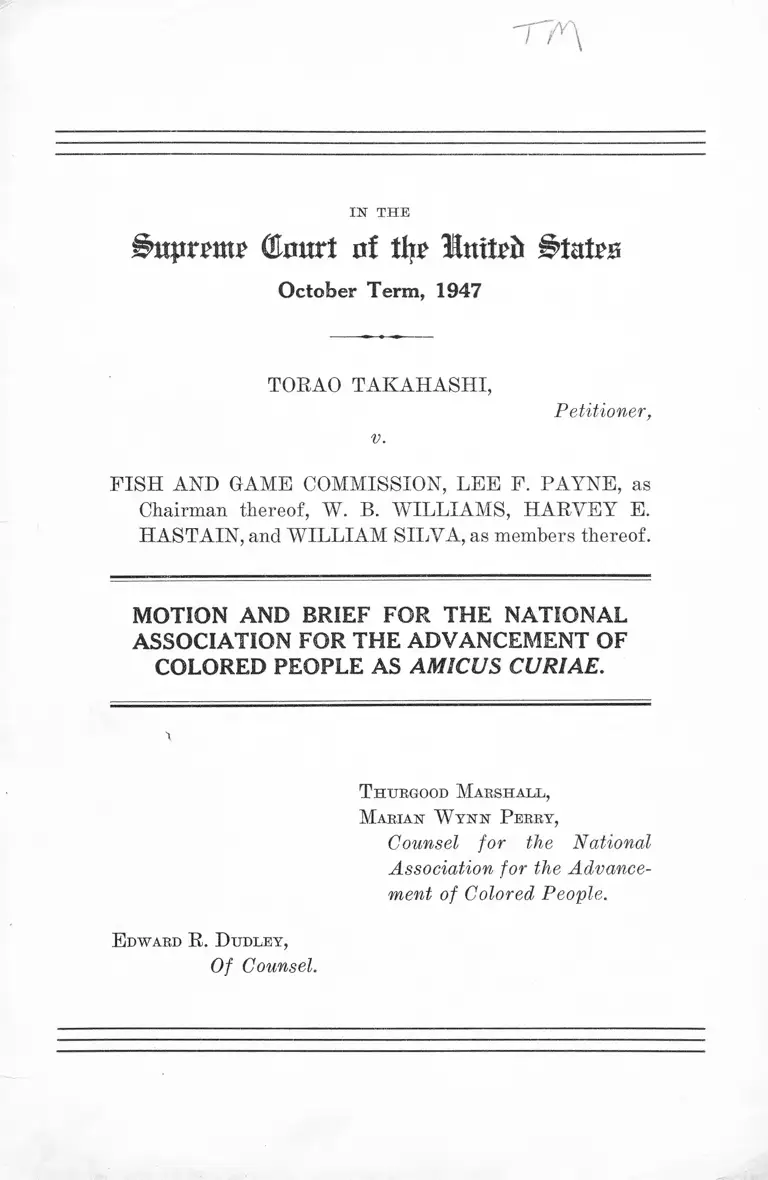

Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1947. cfe29d59-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93bac7ee-ac91-4aa0-a6da-2a1fa31cc5d2/takahashi-v-fish-and-game-commission-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

T T ^

IN THE

(Emxrt of tin' United

October Term, 1947

TORAO TAKAHASHI,

v.

Petitioner,

FISH AND GAME COMMISSION, LEE F. PAYNE, as

Chairman thereof, W. B. WILLIAMS, HARVEY E.

HASTAIN, and W ILLIAM SILVA, as members thereof.

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICUS CURIAE.

T hhegood M arshall ,

M arian W y n n P erry,

Counsel for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People.

E dward R. D udley ,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Brief as amicus curiae--------- 1

Brief for the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People as amicus curiae ------------ 3

Opinion Below and Statute Involved -------------- 3

Questions Presented---------------------------------------- 4

Statement of the Case -------- 4

Reasons for Granting the W r it --------------------------------- 5

Argument:

I— The question presented by the petition is one of

national importance and involves a fundamental

question of constitutional law ___________________ 5

II—A statute denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment 7

III—A state law denying a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates obliga

tions of the Federal Government under the United

Nations Charter ______________________________ 10

Conclusion__________________________________________ 13

Table o f Cases

Allgeyer v. State of Louisiana, 165 U. S. 589 ------------ 9

Baldwin v. G. A. F. Seelig, Inc, 294 U. S. 511, 523 _ _ 7

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 ------------------------ 7

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100________ 8

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, 541 ------------------------- 8

11

PAGE

Oyama v. California, 16 L. W. 4108, — U. S. — (decided

January 19, 1948) ________________________________ 6

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville E. E. Co., 323 U. S.

192_____________________________ ._________________ 9

Truax v. Eaich, 239 IT. S. 33, 42 ______________________ 6

United States v. Belmont, 301 U. S. 324 ___ _________ 11

Yano, Tetsubumi, Estate of, 188 Cal. 645, 239 U. S. 33,

4 2 _______________________ 6

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374 ___________ _ 9

Authorities Cited

Dean Acheson, Acting Secretary of State, Final Eeport

of F. E. P. C_____________________________________ 12

Elliots Debates, 3, p. 515 ___________________________ 11

“ Making the Peace Treaties, 1941-1947“ (Department

of State Publications 2774, European Series 24); 16

State Department Bulletin 1077, 1080-82 _________ 12

McDiarmid, ‘ ‘ The Charter and the Promotion of Human

Eights,” 14 State Department Bulletin 210 (Feb.

10, 1946) ______________________ ,_________________ 12

Eaphael Lemkin, “ Genocide as a Crime under Inter

national Law,” Am. J. of Int. Law, Vol. 41, No. 1

(Jan. 1947), p. 145________________________________ 11

Stettinius’ statement, 13 State Department Bulletin,

928 (May, 1945) __________________________________ 12

U. S. Census, 1940, Characteristics of the Non-White

Population, p. 2 ____ __ _________ __________________ 7

1ST T H E

Bmpvmz dmtrt of % Imtefc

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

COLORED PEOPLE AS AMICUS CURIAE.

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate Jus

tices of the Supreme Court:

The undersigned, as Counsel for the National Associ

ation for the Advancement of Colored People, respectfully

move this Court for leave to file the accompanying brief as

Amicus Curiae in the above entitled appeal.

The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People is a membership organization which for

thirty-eight years has dedicated itself to and worked for the

achievement of functioning democracy and equal justice

under the Constitution and laws of the United States.

October Term, 1947

F ish and Game C om m ission , L ee F .

P ayn e , as Chairman thereof, W. B.

W illiam s , ’ H arvey E. H astain , and

W illiam S ilva , as members thereof.

T oeao T ak ah ash i,

V.

Petitioner,

2

From time to time some justiciable issue is presented to

this Court, upon the decision of which depends the evolution

of institutions in some vital area of our national life. Such

an issue is before the Court now.

The issue at stake in the above entitled petition for

certiorari is the power of a state to discriminate among

persons within its jurisdiction in their exercise of the right

to earn a living in a common occupation. The determina

tion of this issue involves an interpretation of the Four

teenth Amendment which will have widespread effect upon

the welfare of all minority groups in the United States.

T httrgood M arshall ,

M arian W y n n P erry,

Counsel for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People.

E dward E . D udley ,

Of Counsel.

IK T H E

Bnpvmz (tart nf % luttrfc Stairs

October Term, 1947

T okao T ak ah ash i,

Petitioner,

v.

F ish and Gam e C om m ission , L ee F .

P ayne , as Chairman thereof, W. B.

W illiam s , H arvey E. I I astain , and

W illiam S ilva , as members thereof.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION

FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE AS AMICUS CURIAE

Opinion Below and Statute Involved

The opinion below and the statute involved are set forth

in full in the record and in the petition for a writ of certi

orari to this Court and are adopted herein as the statement

of jurisdiction contained in that petition.

3

4

Questions Presented

I

Whether consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment the State of California may deny to a single

class of alien residents of California the right to

earn their living by commercial fishing.

II

Whether consistent with the treaty obligations

of the United States the State of California may

deny to a single class of alien residents of Cali

fornia the right to earn their living by commercial

fishing.

Statement of the Case

The petitioner herein has been a resident of Los Angeles,

California, continuously since 1907 with the exception of

that period of time when he was excluded from California

under the Military Exclusion Laws during World War II.

From 1915 until his exclusion from the state by act of the

Federal Government petitioner earned his living by com

mercial fishing on the high seas, which activity was carried

on pursuant to a license from the Fish and Game Commis

sion of the State of California (R. 1-6). In 1945, the State

of California amended Section 990 of the Fish and Game

Code (Stats. 1945, Ch. 181) so as to forbid the issuance of

a commercial fishing license to a person ineligible to citizen

ship, or to corporations a majority of whose stockholders

or any of whose officers were ineligible to citizenship. IJpon

the face of the statute no other criterion is applied for

licensing. Upon petitioner’s return to California in October,

1945 at the termination of the Military Exclusion Orders

he found himself, after thirty years of employment as a

commercial fisherman, Completely barred from that field of

employment.

5

The petition for certiorari in this Court is to review the

judgment of the Supreme Court of California which, re

versed the holding of the Superior Court which had found

that the Fish and Game Law, as amended, constituted a de

nial of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

The question presented by the petition is one of

national importance and Involves a fundamental ques

tion of constitutional law.

II

A statute denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

III

A state law denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates obligations of

the Federal Government under the United Nations

Charter.

A R G U M E N T

I

The question presented by the petition is one of

national importance and involves a fundamental ques

tion of constitutional law.

The legislation here presented for review was enacted

at a time of strong anti-Japanese hysteria on the west coast

6

which revived the campaign of more than thirty years be

fore to keep the Japanese out of California. This legis

lation like the Alien Land Law of California which was be

fore this Court in Oyama v. California1 was “ designed to

effectuate a purely racial discrimination,” . . . “ is rooted

deeply in racial, economic and social antagonisms” , . . .

and “ racial hatred and intolerance.” 2 Like that law it is

framed “ to discourage the coming of Japanese into this

state.” 3

This Court recognized in Truax v. Raich that:

“ The assertion of an authority to deny to aliens

the opportunity of earning a livelihood when lawfully

admitted to the state would be tantamount to the

assertion of the right to deny them entrance and

abode, for in ordinary cases they cannot live where

they cannot work. And, if such a policy were per

missible, the practical result would be that those law

fully admitted to the country under the authority of

the acts of Congress, instead of enjoying in a sub

stantial sense and in their full scope the privileges

conferred by the admission, would be segregated in

such of the states as chose to offer hospitality.” 4

The end sought by this legislation reverts to the funda

mental proposition upon which our country is founded,

namely whether the states may by individual action divorce

themselves from the common problems of the nation. The

federal government has the exclusive right to determine

whether Japanese aliens may enter this country, but the

position of California asserts the right of state by individual

action to nullify the act of the Federal Government and

effectively exclude aliens from its territory. That such a

1 16 L. W . 4108, — U. S. — (decided January 19, 1948).

2 Ibid., concurring opinion of Mr. Justice M urphy.

8 Estate of Tetsubumi Ya-no, 188 Cal. 645.

4 239 U. S. 33, 42.

7

concept must be rejected is apparent from the words of Mr.

Justice Carbozo in Baldwin v. G. A. F. Seelig, Inc.:

“ The Constitution was framed under the do

minion of a political philosophy less parochial in

range. It -was framed upon the theory that the

peoples of the several States must sink or swim to

gether, and that in the long run prosperity and sal

vation are in union and not division. ’ ’ 5

This language was adopted by this Court in 1941 in uphold

ing the right of citizens freely to move from state to state.6

The unity of our country’s destiny, asserted in 1915 to stem

an hysteria against ‘ ‘ the yellow hordes ’ ’ and in the days of

economic depression to protect the poor and unemployed,

must be reasserted today by this Court if we are to move

forward towards a peaceful and democratic society in a

truly “ United” States.

II

A statute denying to a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates the equal pro

tection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

While the statute on its face purports to have a certain

impartiality by describing the proscribed group as “ per

sons ineligible to citizenship” , the 1940 Census Report7

shows that of 47,305 aliens ineligible to citizenship in the

country, only 1,000 were other than Japanese. Of these,

33,569 were Japanese aliens residing in California.

Having so recently reviewed the legislative history of

the California Alien Land Law in the Oyama case, this

5 294 U. S. 511, 523.

6 Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.

7 U. S. Census, 1940, Characteristics of the Non-White Popula

tion, p. 2.

Court cannot fail to recognize the same purpose and the

same undemocratic motivation in the enactment of a law

barring Japanese from a common occupation in the State

of California. It remains only to be considered whether

there is any reasonable basis which can be legally justified

under the Fourteenth Amendment, for the classification of

Japanese as a group ineligible to engage in commercial

fishing.

“ Such a rational basis is completely lacking

where, as here, the discrimination stems directly

from racial hatred and intolerance. The Constitution

of the United States, as I read it, embodies the high

est political ideals of which man is capable. It in

sists that our government, whether state or federal,

shall respect and observe the dignity of each indi

vidual whatever may be the name of his race, the

color of his skin or the nature of his beliefs. It thus

renders irrational, as a justification for discrimina

tion, those factors which reflect racial animosity.” 8

As stated by this Court, through Mr. Justice H olmes, in

Nixon v. Herndon: 9 “ States may do a good deal of classi

fying that it is difficult to believe rational, but there are

limits, and it is . . . clear . . . that color cannot be made the

basis of statutory classification.” The cold statistics of the

number of ineligible aliens affected by this statute10 sweep

away any contention that its basis is not the “ yellow color”

of the Japanese. It is of such color legislation that this

Court stated in Hirabayashi v. United States:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a

8 Concurring opinion of Mr. Justice M urphy, in Oyamct v. Cali

fornia, supra.

9 273 U. S. 536, 541.

10 See footnote 1, supra.

9

free people whose institutions are founded upon the

doctrine of equality. For that reason, legislative

classification or discrimination based on race alone

has often been held to be a denial of equal protec

tion. ’ ’ 11

^

“ No reason for it is shown, and the conclusion

cannot be resisted, that no reason for it exists except

hostility to the race and nationality to which the

petitioners belong and which in the eye of the law

is not justified. The discrimination is therefore

illegal. . . . ’ ’ 12

This Court has long recognized that the Fourteenth

Amendment guarantees the right of persons within the

jurisdiction of a state not only “ to be free from the mere

physical restraint of his person” but also “ to earn Ms

livelihood by any lawful calling; to pursue any livelihood

or avocation, and for that purpose to enter into all con

tracts which may be proper, necessary, and essential to

his carrying out to a successful conclusion the purposes

above mentioned.” 13 Even the action of private associa

tions sanctioned indirectly by the state or federal govern

ment, in excluding persons from employment because of

race have been held prohibited by constitutional limita

tion.14

The legislation of the State of California seeking to pre

vent Japanese from engaging in a common occupation has

no rational basis. Being based solely on race, it comes into

fatal conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.

11 320 U. S. 81, 100.

12 Yick W o v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 374.

13 Allgeyer v. State o f Louisiana, 165 U. S. 589.

14 Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192.

10

III

A state law denying a racial group the right to

engage in a common occupation violates obligations of

the Federal Government under the United Nations

Charter.

As set forth above in Point 1, the United States Govern

ment has sole jurisdiction to admit aliens into the United

States. Once such aliens are admitted they become entitled

to those constitutional protections which under our form

of government are afforded to all persons regardless of

citizenship. More recently they have been afforded an

added protection by the aet of the United States in sub

scribing to the United Nations Charter, Article 55 of which

has pledged this country to promote “ universal respect

for, and observance of human rights and fundamental free

doms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language

or religion.”

The United Nations Charter is a treaty, duly executed

by the President and ratified by the Senate (51 Stat. 1031).

Under Article VI, Section 2 of the Constitution such a

treaty is the “ supreme Law of the Land” and specifically,

“ the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any

Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the

Contrary notwithstanding. ’ ’

The right to work has long been recognized as a funda

mental human right in American law.15 The laws of Cali

fornia attempt to deny to Japanese this fundamental right

in contravention of the international obligations of the

United States.

15 Allgeyer v. State o f Louisiana, Steele v. Louisville & Nashville

R. R. Co. and Truax v. Raich, supra.

31

Historically, no doubt has been entertained as to the

supremacy of treaties under the Constitution. Thus Madi

son, in the Virginia Convention, said that if a treaty did

not supercede existing state laws, as far as they contra

vene its operation, the treaty would be ineffective.

“ To counteract it by the supremacy of the state

laws would bring on the Union the just charge of

national perfidy, and involve us in war. ’ ’ 18

While it is true that Japan is not a party to the United

Nations Charter, the treaty obligations of the United States

under the Charter are not limited simply to nationals of

the other member nations. It has now become clear by

the action of our own government and of other governments

in international affairs that the treatment of any minority

group within any country is a proper subject of inter

national negotiations.16 17

Official spokesmen for the American State Department

have expressed concern over the effect racial discrimination

in this country has upon our foreign relations and the then

Secretary of State, Edward R. Stettinius, pledged our

16 3 Elliots Debates 515; see also United States v. Belmont, 301

U. S. 324— “ In respect of all international negotiations and compacts,

and in respect of our foreign relations generally, state lines disappear.

As to such purposes the state of New York does not exist. Within

the field of its powers, whatever the United States rightfully under

takes, it necessarily has warrant to consummate. And when judicial

authority is invoked in aid of such consummation, State Constitutions,

state laws, and state policies are irrelevant to the inquiry and deci

sion.”

17 See Raphael Lemkin, “ Genocide as a Crime under International

Law,” Am. J. of Int. Law, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan. 1947), p. 145.

12

government before the United Nations to fight for human

rights at home and abroad.18 19

The interest of the United States in the domestic affairs

of the nations with whom we have signed treaties of peace

following World War IT can be seen from the provisions

in the peace treaties with Italy, Bulgaria, Hungary and

Rumania, and particularly with settlement of the free terri

tory of Trieste, in all of which we specifically provided for

governmental responsibility for a non-discriminatory prac

tice as to race, sex, language, religion, and ethnic origin.10

Our interest was in no way limited to treatment of Ameri

can nationals.

The federal government having acted in the field of

International Law and pledged our government to protect

human rights and fundamental freedoms, no state within

the union has the right to deny to any person such right

or freedom upon racial grounds.

There cannot be any question that this legislation vio

lates the letter and the spirit of the treaty obligations of

the United States and under our Constitution must fall be

fore the superior power of such treaty.

18 McDiarmid, “ The Charter and the Promotion of Human Rights,”

14 State Department Bulletin 210 (Feb. 10, 1946) ; and Stettinius’

statement, 13 State Department Bulletin, 928 (May, 1945). See also

letter of Acting Secretary of State Dean Acheson to the F. E. P. C.

published at length in the Final Report of F. E. P. C. reading in part,

“ the existence o f discrimination against minority groups in this coun

try has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries.”

19 See description of these provisions in, “ Making the Peace Trea

ties, 1941-1947” (Department of State Publications 2774, European

Series 24) ; 16 State Department Bulletin 1077, 1080-82.

Conclusion

The actual effect of the California statute is to deny

upon the basis of race, to a group of persons residing

therein a right secured to all other persons. That this is

discrimination under the Fourteenth Amendment has been

clearly established in numerous cases before this Court.

The Constitution protects all persons from discriminatory

state action solely on the basis of race and prohibits the

unequal application of the law.

It is respectfully submitted that the issues raised by the

petition for certiorari are of such grave importance that

this Court should review the decision of the court below.

T hurgood M arshall ,

M arian W y n n P erry,

Counsel for the National

Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People.

E dward R. D udley ,

Of Counsel.

L aw yers P ress, I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300