Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 22, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. City of Roanoke School Board Opinion, 1962. 87f80c33-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/93c995cb-0b60-44a9-be6a-a338494d2991/green-v-city-of-roanoke-school-board-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

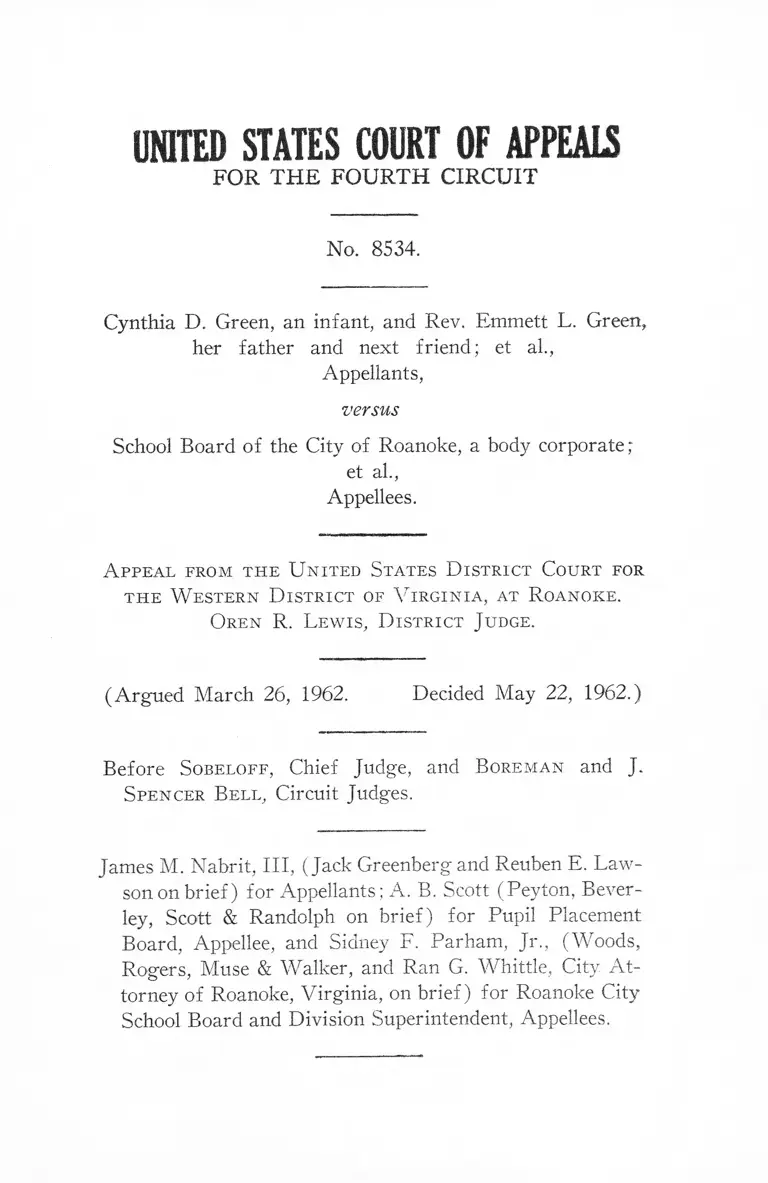

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 8534.

Cynthia D. Green, an infant, and Rev. Emmett L. Green,

her father and next friend; et al.,

Appellants,

versus

School Board of the City of Roanoke, a body corporate ;

et al.,

Appellees.

A p p e a l f r o m t h e U n it e d S t a t e s D i s t r ic t C o u r t f o r

t h e W e s t e r n D is t r ic t o f V i r g i n i a , a t R o a n o k e .

O r e n R . L e w i s , D is t r ic t J u d g e .

(Argued March 26, 1962. Decided May 22, 1962.)

Before S o b e l o f f , Chief Judge, and B o r e m a n and J.

S p e n c e r B e l l , Circuit Judges.

James M. Nabrit, III, (Jack Greenberg and Reuben E. Law-

son on brief) for Appellants; A. B. Scott (Peyton, Bever

ley, Scott & Randolph on brief) for Pupil Placement

Board, Appellee, and Sidney F. Parham, Jr., (Woods,

Rogers, Muse & Walker, and Ran G. Whittle, City At

torney of Roanoke, Virginia, on brief) for Roanoke City

School Board and Division Superintendent, Appellees.

2

S o b e l o f f , Chief Judge:

This action was begun in the District Court for the

Western District of Virginia by twenty-eight Negro public

school pupils and their representatives in the City of

Roanoke to require the defendants to grant them transfers

from Negro to white schools. The plaintiffs also prayed for

an injunction against the continued operation of racially

segregated schools in the city or for an order requiring

city and state school officials to submit and effectuate a

plan for desegregation.

Before turning to the facts pertaining to these plain

tiffs, it is in order to describe the operation of the Roanoke

public school system, as revealed by the record. The Vir

ginia Legislature has by statute entrusted authority for

the enrollment and placement of pupils in the state to the

Pupil Placement Board located in Richmond, Va. Code

Ann. §22-232.1—232.17 (Supp. 1960), unless a particular

locality elects to assume sole responsibility for the assign

ment of its pupils, Va. Code Ann. §22-232.18—232.31

(Supp. 1960). However, the Roanoke City school board

has not elected to assume this responsibility, and insists

that legal responsibility for assignments is in the state

board.

In practice, the state Pupil Placement Board’s role in

the assignment of pupils is largely a formality. The Roa

noke City school officials make recommendations to the

Pupil Placement Board as to the assignment of every pupil

in the city. If the parents or guardians do not object to the

recommended assignments, the recommendations are

routinely approved by the state board. In fact, such recom

mendations are not even presented to the three members

of the state board, but are automatically approved by the

3

state board's staff. Nor do the state board members con

cern themselves with the criteria applied by the local school

authorities in making recommendations. In this way, as

many as 10,000 pupils have been assigned to schools by

the state board in a single morning. Only when recom

mendations of the local officials are protested by parents,,

or, as is the case with some applications for transfer from

one school to another, when the local officials fail to make

any recommendations at all, do the members of the state

Pupil Placement Board personally consider individual as

signments.

The scheme employed by the school officials in Roanoke

City in making their recommendations is aptly called the

“feeder” system. The city schools are divided into six

sections, numbered I to VI. A pupil, when he first enters

the city’s school system, is assigned to an elementary school

in one of the sections. When he graduates from the ele

mentary school, he is automatically assigned to the junior

high school which serves that same section. Similarly, upon

graduation from junior high school, he goes to his sec

tion’s senior high school. Under this arrangement, the

initial assignment of a pupil to an elementary school ef

fectually determines what schools he will attend during

his entire school career, unless he succeeds in obtaining a

transfer to a school in another section. These sections,,

however, serve no specifically defined areas. The city

school superintendent stated that initial assignments to

elementary schools are in accordance with what he called

a “neighborhood” system: pupils simply go to the school

in their vicinity. While the superintendent admitted that

he could produce no map describing the sections on the

basis of definite geographical boundaries, he asserted that

the principal of each school knows the neighborhood his

4

school serves. However, when it comes to Negro pupils,

there is no relationship between these sections and the

vague geographical neighborhoods. Rather, all Negroes

are initially assigned to schools in section II, and graduate

to section II junior and senior high schools. And no

whites attend schools of that section. In other words, the

“neighborhood” served by section II school consists of

the entire Negro community in the city.

As previously pointed out, recommendations by the

city officials for assignment in accordance with this

system are routinely approved by the State Pupil Place

ment Board. When recommendations by the local of

ficials for assignments are protested by parents, or when

the local officials make no recommendations, as noted

before, the members of the state Pupil Placement Board

personally consider the assignments. This, it was estimated,

happens in only 1/100 of 1% of the total number of

assignments. Before making any decisions, the state board

requests the local officials to furnish additional informa

tion about each pupil. Included in the information requested

are the occupations of the parents, the schools attended

by the pupil’s brothers and sisters, the distances between

the pupil’s home and both the school he presently attends

and the school he wishes to attend, his scholastic aptitude

and achievement as revealed by standard, state-wide tests

and by his grades, and the comments of the pupil’s former

teachers. An informal meeting is then held by the state

board with the local school officials, and, on the basis of this

information, the state board passes on the application. The

manner in which the state board applies this information in

reaching a decision can best be illustrated by the cases of the

twenty-eight plaintiffs and eleven others who, in 1960, ap

plied for transfers.

5

Prior to 1960, the Roanoke City schools were completely

segregated, with all Negro pupils attending section II

schools and all whites attending schools in the other five

sections. In that year, the thirty-nine Negro pupils, in

cluding the twenty-eight plaintiffs, filed applications for

transfers to all-white schools. These were forwarded to

the state board without recommendations. The state board

then requested from the local authorities the information

concerning residence, aptitude, and so forth. When the

Roanoke City school superintendent asked to be advised

more specifically what information was desired, a member

of the state board replied with revealing candor that the

board wanted information to help them answer three ques

tions, described in the following testimony of the school

superintendent:

“Are there Negro pupils who cannot be excluded from

attending white schools except for race? That is num

ber one. Number two: Would the Superintendent and

School Board so certify to the Pupil Placement Board ?

Number three: And in our judgment, what would

happen in the local communities if some Negro pupils

were assigned to white schools ? Those were the three

questions.”

The requested data was transmitted, and subsequently, on

August 15, 1960, at a meeting of the state board with the

city superintendent, the latter expressed his judgment as

to which applications could not be denied but for race and

which could. In every case, these judgments were effec

tuated as the actions of the state board. Of the thirty-nine

applications, the state board granted nine and denied thirty.

These nine were the first Negroes to be admitted to white

schools in Roanoke City since the Supreme Court’s deci

6

sions in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), 349 U.S. 294 (1955). Most of the parents of the

thirty-nine pupils were notified of the board’s decision on

August 17, 1960, and the remainder on August 22. There

upon, the parents of twenty-eight of the thirty pupils whose

applications had been denied filed the present action in

the District Court.

With respect to the nine Negro children who were

granted transfers, the minutes of the state Pupil Place

ment Board recite that the local school authorities, applying

“criteria and standards * * * which are regarded by this

Board as valid and reasonable, * * * are not in a position

to oppose legally the * * * assignments and transfers * *

As to the twenty-eight plaintiffs, their applications

were denied for a variety of reasons.1 Eleven were re

jected on the ground that they lived closer to the Negro

school to which they were assigned than to the white

schools they wished to attend, although actually one of

the eleven lived a block closer to the white school and

another lived equidistant between the two schools. Twelve

of the plaintiffs were denied transfers because the results

of their aptitude and achievement tests placed them below,

or in a few cases only slightly above, the median of the

classes in the white schools they wished to attend. Five

were refused on the ground that, although the applicants

had otherwise met the board’s standards, each had a brother

or sister attending the same school with him, whose aptitude

and achievement tests were below the median of the com

parable white classes. The board professed to rely upon

these “standards,” other than the residence requirement,

1 The record does not reveal the reason for the board’s denial of the ap

plications of the two pupils who did not join as plaintiffs in this action.

7

to avoid placing any Negroes in white schools “who would

be failures.”

In the District Court, the defendants first contended that

the suit should be dismissed because the plaintiffs, after

their applications were denied, did not further protest

against the assignments by the state board and seek a hear

ing in accordance with the provisions of section 22-232.8

of the Pupil Placement Act. Yra. Code Ann. §22-232.8

(Supp. 1960). The court, however, rejected this argument,

stating: “In this case, the transfer requests were denied

five or six days prior to the commencement of the school

term. Obviously there was insufficient time to have heard

a protest if one had been filed.” While the defendants have

not renewed this particular argument, both parties in their

briefs before this court have raised and argued more gen

eral questions concerning the procedural adequacy of the

administrative remedies and the necessity for exhausting

them. However, we think that the above-quoted answer of

the District Court fully meets the particular question with

respect to these plaintiffs, and thus it is unnecessary to

deal with or decide broader issues concerning administra

tive remedies. The District Court also denied the plain

tiffs’ prayers for an injunction against the continued opera

tion of a racially segregated school system or for an order

requiring a plan for desegregation.

The court ruled on the denials of the plaintiffs’ applica

tions as follows: As to the eleven who were denied transfers

on the ground of residence, the District Court sustained the

defendants’ actions. In regard to the twelve plaintiffs whose

applications were denied on the basis of academic qualifica

tions, the court upheld the denial as to one who had per

formed very poorly in the aptitude test, ordered the admis

sion of one who was academically well above the median of

8

those pupils in the white shcool to which she was applying,

and ordered the state board to re-examine the applications of

the other ten. With respect to the five plaintiffs whose

applications were denied because they had brothers or

sisters attending the Negro school to which they had been

assigned, the District Court also ordered the state board to

re-examine the applications. Of the fifteen applications

thereafter re-examined by the state board, five were allowed

by the board and ten denied, leaving a total of twenty-two

plaintiffs whose applications were denied. Of these, two were

permitted to transfer to white schools for the 1961-62

school year, leaving twenty of the plaintiffs who- have

failed thus far to secure relief. These twenty are the ap

pellants in the present appeal.

This court has on several occasions recognized that

residence and aptitude or scholastic achievement criteria

may be used by school authorities in determining what

schools pupils shall attend, so long as racial or other

arbitrary or discriminatory factors are not considered. See,

e.g., Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

Virginia, 289 F.2d 439, 442 (4th Cir. 1961) ; Jones v. School

Board of City of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F.2d 72, 75

(4th Cir. 1960). But if these criteria, otherwise lawful,

are used in a racially discriminatory manner, the resulting

assignment is not saved from illegality. As we have more

than once made clear, school assignments, to be constitu

tional, must not be based in whole or in part on considera

tions of race. Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottes

ville, Virginia, supra; Hill v. School Board of City of Nor

folk, Virginia, 282 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960); Jones v.

School Board of City of Alexandria, Virginia, supra.

The pupil assignment system in effect in the City of Roa

noke, as administered by the joint efforts of the local

9

school authorities and the state Pupil Placement Board, is,

as demonstrated by the facts, infected throughout with

racially discriminatory applications of assignment criteria.

All initial assignments of children enrolling in the

city’s school system are on a completely racial basis.

Every white child is initially assigned to a school in a

section other than section II, regardless of how near

he might reside to a section II school. Every Negro child,

on the other hand, is initially assigned to a section II school,

regardless of his place of residence or any other criteria.

The Negro child, if he desires a desegregated education,

must thereafter run the gauntlet of numerous transfer

criteria in order to extricate himself, if he can, from the

section II schools. These are hurdles to which a white

child, living in the same area as the Negro and having the

same scholastic aptitude, would not be subjected, for he

would have been initially assigned to the school to which

the Negro seeks admission. In Jones v. School Board of

City of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F.2d 72, 77 (4th Cir.

1960), this practice was expressly condemned:

“* * * if the criteria are, in the future, applied only

to applications for transfer and not to applications

for initial enrollment by children not previously at

tending the city’s school system, then such action

would also be subject to attack on constitutional

grounds, for by reason of the existing segregation

pattern it will be Negro children, primarily, who seek

transfers.”

Or, as we stated in Hill v. School Board of City of Nor

folk, Virginia, 282 F.2d 473, 475 (4th Cir. 1960), where

10

“* * * assignments to the first grade in the primary

schools are still on a racial basis, and a pupil thus

assigned to the first grade still is being required to

remain in the school to which he is assigned, unless,

on an individual application, he is reassigned on the

basis of the criteria which are not then applied to

other pupils who do not seek transfers * * *, such an

arrangement does not meet the requirements of the

law.”

Steps must be taken to end this unlawful initial assign

ment arrangement which the record discloses to exist in

the City of Roanoke. It is a racially discriminatory ap

plication of assignment criteria to which all of the appel

lants were subjected.

Beyond the discrimination inherent in the initial as

signment system, there appear to be constitutional infirmi

ties with respect to the application of the criteria for

transfers from one Roanoke school to another. The re

quirement that a Negro seeking transfer must be well

above the median of the white class he seeks to enter is

plainly discriminatory. The board’s explanation that this

special requirement is imposed on Negroes to assure

against any “who would be failures” is no answer. The

record discloses that no similar solicitude is bestowed upon

white pupils. Similarly, the requirement that a pupil’s

brothers and sisters be above the median of corresponding

classes in the school to which transfer is sought is invoked

discriminatorily against only Negro children who seek to

escape from segregated schooling. Moreover, the very

manner of the state board, which seeks information con

cerning Negro applications for transfers, points up the

extent that such applications are viewed differently from

11

white applications. Specifically, the board wanted to know

if there were any “Negro pupils who cannot be excluded

from attending white schools except for race?” The

board’s preoccupation was with race, and its approach was

to find some excuse for denying the Negroes’ applications

for transfers. A candid view of the record compels the

observation that, as to white children, there is no com

parable straining to ferret out some pretext for denying

transfers.

The federal courts have uniformly held that such unequal

application of transfer criteria is a violation of the Negro

pupils’ rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. As we

stated in Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, Vir

ginia, 278 F.2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960) : “If the criteria

should be applied only to Negroes seeking transfer or enroll

ment in particular schools and not to white children, then

the use of the criteria could not be sustained.” See North-

cross v. School Board of City of Memphis, F.2d

, (6th Cir. 1962) ; Dodson v. School Board of

City of Charlottesville, Virginia, 289 F.2d 439, 443 (4th

Cir. 1961); Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798, 803, 806-

09 (8th Cir. 1961); Hill v. School Board of City of Nor

folk, Virginia, 282 F.2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960) : Mannings

v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F.2d 370, 374-75 (5th

Cir. 1960) ; Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Virginia, 264 F.2d 945, 946 (4th Cir. 1959);

School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v.

Allen, 240 F.2d 59, 64 (4th Cir. 1956).

In sum, the Roanoke City school officials, together with

the state Pupil Placement Board, have administered a

school system where pupils of the Negro race are classified

in a separate category, are in the first instance completely

12

segregated in their own attendance area, and are kept in

that area, except for the few who can meet transfer

standards which, for the most part, have no application to

white pupils. “Obviously the maintenance of a dual system

of attendance areas based on race offends the constitu

tional rights of the plaintiffs and others similarly situated

and cannot be tolerated.” Jones v. School Board of the

City of Alexandria, Virginia, 278 F.2d 72, 76 (4th Cir.

1960). As administered, the Pupil Placement Law offends

the constitutional rights of the plaintiffs and of others

similarly situated. Thus, the individual appellants are

entitled to relief, and also they have the right to an in

junction on behalf of the others similarly situated. See

School Board of the City of Charlottesville, Virginia v.

Allen, 240 F.2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956), sustaining the right

of the plaintiffs to obtain a general injunction against the

school officials prohibiting racial discrimination in the

administration of the schools, and Frasier v. Board of

Trustees of University of North Carolina, 134 F. Supp.

589, 593 (M.D.N.C. 1955) (three-judge court), aff’d,

per curium, 350 U.S. 979 (1956), ordering an injunction

against discriminatory admissions to the University of

North Carolina.2

As the defendants have disavowed any purpose of using

their assignment system as a vehicle to desegregate the

schools and have stated that there was no plan aimed at

ending the present practices which we have found to be

discriminatory, this case is quite unlike Hill v. School

2 Accord, Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

F.2d (6th Cir. 1962) ; Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F.2d

370, 372-75 ( 5th Cir. 1960) ; Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F.2d

156, 165 (5th Cir. 1957).

13

Board of City of Norfolk, Virginia, 282 F.2d 473 (4th

Cir. 1960), and Dodson v. School Board of City of Char

lottesville, Virginia, 289 F.2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961). In

those cases, the assignment practices were defended as

interim measures only and the district courts, recognizing

the infirmities in the existing practices, made it clear that

progress toward a completely nan-discriminatory school

system would be insisted upon. These factors are totally

absent from the instant case.

However, if, upon remand, the defendants desire to

submit to the District Court a plan for ending the existing

discriminatory practices, then, rather than the appellants

and others similarly situated all being entitled to immediate

admission to non-segregated schools, their admissions may

be in accordance with the plan. Any such plan, before being

approved by the District Court, should provide for im

mediate steps looking to the termination of the discrimina

tory practices “with all deliberate speed” in accordance with a

specified time table. Hill v. School Board of City of Nor

folk, Virginia, 282 F.2d 473, 475 (4th Cir. 1960).

Reversed and remanded for

proceedings consistent with

this opinion.

Adm. Office, U. S. Court—3141—5-26-61—100—Lawyers Printing Co., Richmond 7, Va.