Correspondence from Wilson to Guinier

Correspondence

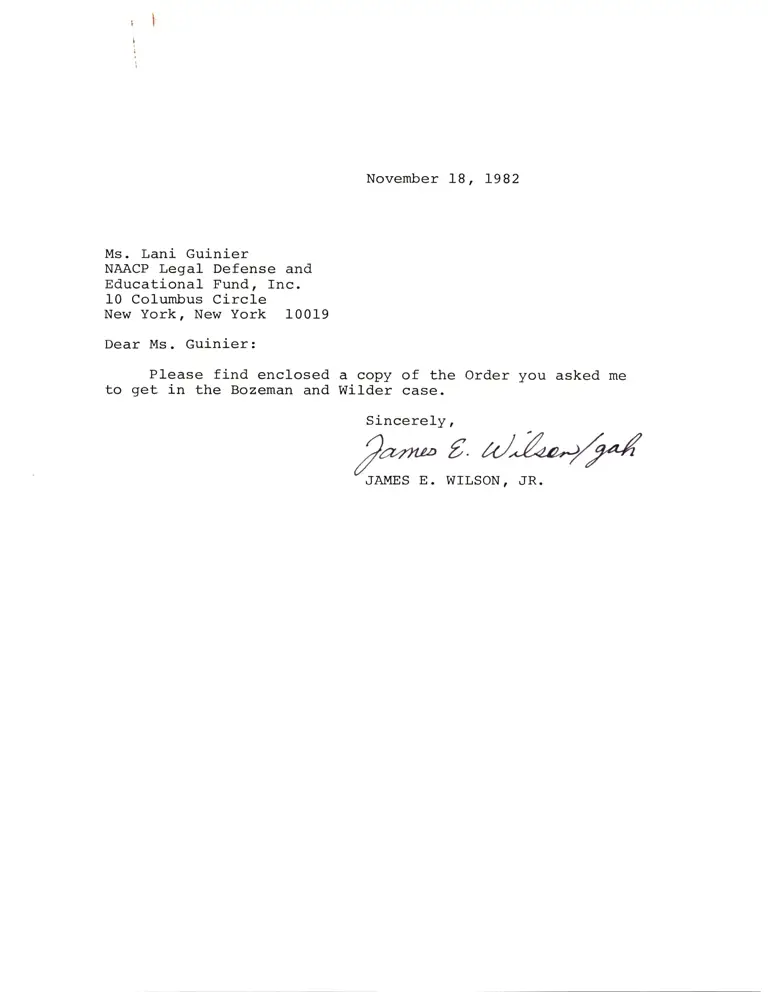

November 18, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Correspondence from Wilson to Guinier, 1982. 7c06a57a-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/94ba650e-6a88-4323-8efa-bc63409cfcf5/correspondence-from-wilson-to-guinier. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

rl

November 18, 1982

Ms. Lani Guinier

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Dear Ms. Guinier:

Please find enclosed a copy of the Order you asked me

to get in the Bozeman and Wilder case.

Sincerely,

2rr',r-, k/;b)Z-/

JAi\,IES E. WILSON, JR.

$1. d Erl

STATE OF AIABA}IA

PICKENS COI]NTY

CIRCUIT COURT

STATE OF AIABAMA, ex rEl

P. M. Johnston, Dlstrict

Attorney, Twenty-Fourth

Judlclal Circult of Alabama,

Petltioner'

VS. ,

::Xllr:'^i:1ffi:'

si'"rrr or Pickens

Defendant.

This cause belng heard by the Court, by agreement of the parties, on the

2 Ou, of October, L978, and being submltted to the Court on the verified Petitlon

of the Dlstrlct Attorney, and it appeeiring to the Court that there ls probable cause

for believing that evldence of fraud or criminal offenses is contained withln the

Absentee Ba1lot boxes used ln the Democratic Prlmary Electlon of September 5, L978,

and the DemocratLc prlmary Run-off Electlon of Septernber'26, 1978; and lt further

appearllng to the Court that lt ls necessary that the Absentee Bal-lot boxes used ln

the aforesaLd.Electlons be opened and the contents thereof examined; and that such

evldence as nay be eonEalned ln sald boxes be presenred for consideratLon by the

Grand Jury of Plckens CountY-

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED BY THE COURT: !

l-. Louie C. Co}eman, Sherlff of PIckenB County, lu enJoLned and prohibited from

destroying the Absentee Ballot boxes and the conte.nts thereof .used in the Democratlc

primary Election of september 5, 1978, and the Democratic Primary Runloff Electlon of

september 26, 1978, pendlng the further order of thls court

2. Louie C. CoLeman, Sherlff of Pickens County and custodian of said Absentee

BaLlot boxes, is orclererl to dellver sald Absentee BaILot boxes'forthwith to the Court.

3. The Distrlct Attorney ls ordered to oPen saLd Absentee BalLot boxes and

examine the contents thereof for possLble presentatlon of any evLdenee found the:

I

crsz w.Ct-7?- o Q{

/'/,

to the Grand Jury of Plckens County'

Ficruus couNTY

't

l;

-/t 7