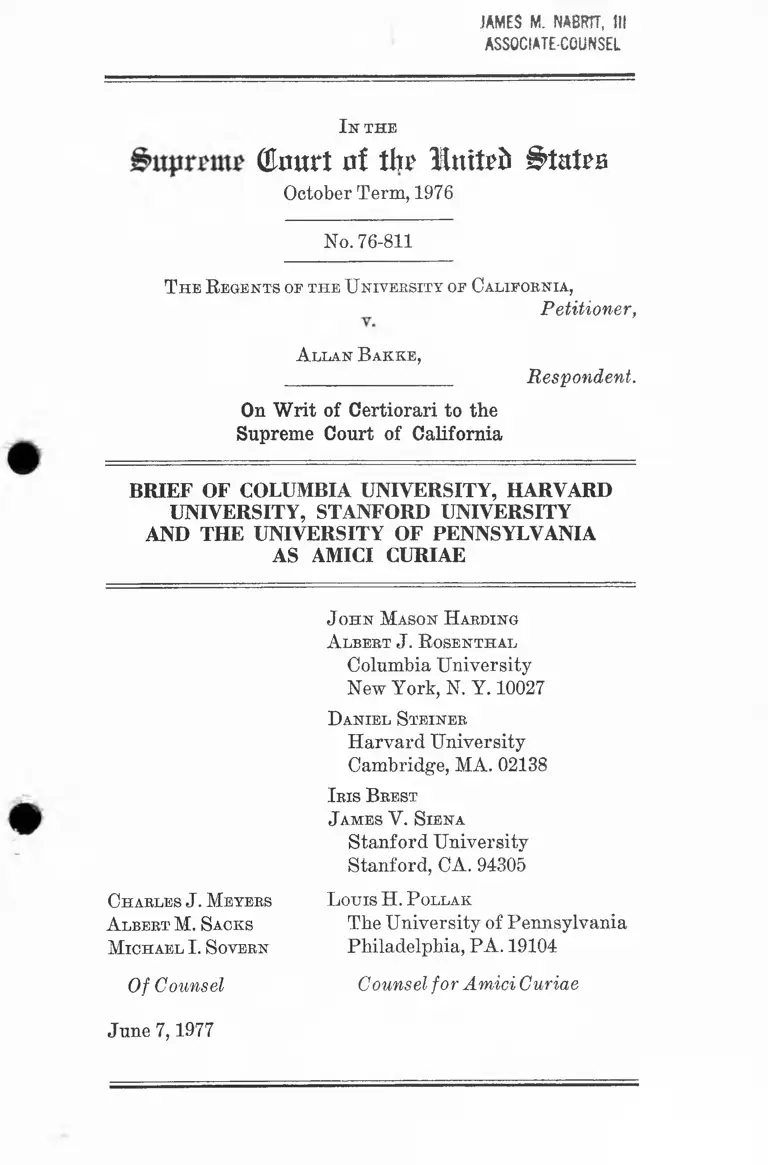

Bakke v. Regents Brief of Columbia University, Harvard University, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 7, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of Columbia University, Harvard University, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania as Amici Curiae, 1977. 1c06c147-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/95e4cd82-ee62-4214-96ce-ad7673ec2d15/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-columbia-university-harvard-university-stanford-university-and-the-university-of-pennsylvania-as-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NABRTT, lit

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

I n t h e

Olourt of tin United Btutm

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R egents oe t h e U n iv ersity of Ca lifo rn ia ,

Petitioner,

A llan B a k k e ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, HARVARD

UNIVERSITY, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

AND THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

AS AMICI CURIAE

C h arles J . M eyers

A lbert M . S acks

M ic h a e l I . S overn

Of Counsel

June 7,1977

J o h n M ason H arding

A lbert J . R o sen th a l

Columbia University-

New York, N. Y. 10027

D a n ie l S t e in e r

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA. 02138

I r is B rest

J am es V . S ie n a

Stanford University

Stanford, CA. 94305

Louis H. P ollak

The University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA. 19104

Counsel for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

P age

I n ter est oe t h e A m ic i C u r i a e ............................................. 1

S um m a ry oe A r g u m en t ......................................................... 8

A r g u m e n t ..................................................................................... 11

I. The Inclusion of Qualified Minority Group Mem

bers in a Student Body Serves Important Educa

tional Objectives .............................................. 11

II. Unless Race May Be Considered in Admissions

Decisions, Selective Institutions Will Not Be

Able to Achieve Adequately Diverse Student

Bodies While Maintaining Other Significant

Educational Values ........................................... 14

A. Minority Status Must Be Considered Inde

pendently of Economic or Cultural Depriva

tion .............................................................. 17

B. Use of a Racially Neutral Standard of “ Dis

advantage” Would Reduce the Number of

Minority Matriculants ................................ 18

C. Other Alternatives Suggested by the Su

preme Court of California Would Also Be In

effective ....................................................... 22

III. The Judgment of the Supreme Court of Califor

nia Should Be Reversed.................................... 24

C on clu sio n ................................................................................... 39

Appendix 1

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: P age

Alevy v. Downstate Medical Center, 39 N.Y. 326, 348

N.E. 2d 537, 384 N.Y.S. 2d 82 (1976)..................... 34

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts v.

Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied,

416 TJ.S. 957 (1974) .............................................. 29

Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 18

Cal. 3d 34, 553 P.2d 1152,132 Cal. Rptr. 680 (1976) 19

Borden’s Farm Products Co. v. Baldwin, 293 U.S.

194 (1934) ............................................................. 37

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 30

Califano v. Webster, 97 S. Ct. 1192 (1977) ............ 29

Carterv. Gallagher,452P.2d327 (8th Cir.) (enbanc),

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) ........................... 28

Chastleton Corp. v. Sinclair, 264 U.S. 543 (1924) 33, 37

Chicago & Grand Trunk By. v. Wellman, 143 U.S.

339 (1892) ............................................................ 37

City of Hammond v. Schaffi Bus Line, 275 U.S. 164

(1927) .................................................................... 37

Contractors Ass’n of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secre

tary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 854 (1971) .............................................. 28

Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190 (1976)........................... 34

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) ............ 34

Hamilton v. Regents of University of California, 293

U.S. 245 (1934) ..................................................... 26

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974) ....................... 29

Massachusetts Board of Retirement v. Murqia, 427

U.S. 307 (1976) .................................................... 35

McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 U.S. 637 (1950) ............ 13

Ill

P age

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v, Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938) ....................................................................

Morales v. New York, 396 U.S. 102 (1969)................

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ..................

Naim v. Naim, 350 U.S. 891 (1955) .........................

North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43 (1971)..................................................

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970)...................

Polk Co. v. Glover, 305 U.S. 5 (1938) .......................

Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U.S. 549 (1947)

San Antonio Independent School District v, Rodri

guez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973) .........................................

Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 U.S. 498 (1975) ............

South Carolina v. Katsenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) .........................................

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ....................

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1957).......

25

37

29

37

28

35

37

37

10, 31,

34,35

29

31

28, 32

25

10,

25, 26

Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4

Wheat. 518 (1819) ....................................... . 26

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996 (1977)................................ 28,

29,30

United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S.

144 (1938) ............................................................ 10,

34, 35

United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers Local

46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 412 U.S.

939 (1973) ............................................................ 28

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §1981 (1970) . .

42 U.S.C. §2000 (d) (1970)

iv

P age

6

5

Miscellaneous:

Atelsek & Gomberg, Bachelors Degrees Aivarded to

Minority Students, 1973-1974 (Higher Education

Panel Eeports, No. 24, American Council on Educa

tion 1977) .............................................................. 21

Brief for the Deans of the California Law Schools in

Favor of the Petition for Certiorari.................... 33

Brown, Minority Enrollment and Representation in

Institutions of Higher Education (Ford Founda

tion Report by Urban Ed., Inc. 1974) ................... 21,

28, 34

Brown & Stent, Black College Undergraduates, En

rollment and Earned Degrees, 6 J. Black Stud. 5

(1975) .................................................................... 21

B. Caress & J. Kossy, The Myth of Reverse Discrimi

nation: Declining Minority Enrollment in New

York City’s Medical Schools (Health Policy Advi

sory Center Inc. 1977) ..........................................

A. Carlson & C. Werts, Relationships Among Law

School Predictors, Law School Performance, and

Bar Examination Results (E.T.S. 1976) .............. 22

Educational Testing Service, Graduate and Profes

sional School Opportunities for Minority Students

(6th ed. 1975-77) ................................................... 21,34

Frankfurter, A Note on Advisory Opinions, 37 Harv.

L. Rev. 1002 (1924)................................................ 38

Gunther, In Search of Evolving Doctrine on a Chang

ing Court: A Model for a Newer Equal Protection,

86 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1972) ..................................... 34

20,

23, 28

V

P age

Hutchins, Reitman, & Klaub, Minorities, Manpower,

and Medicine, 42 J. Med. Educ. 809 (1967)............ 3

Knauss, Developing a Representative Legal Profes

sion, 62 A.B.A. J. 591 (1976) ................................ 21

Law School Admission Council, Law School Admis

sion Bulletin 1976-1977 (E.T.S.) .......................... 22

M. Miskel, Minority Student Enrollment, Research

Currents, Nov. 1973 (ERIC Clearing House on

Higher Education)................................................ 20

Monaghan, Constitutional Adjudication: The Who

and When, 82 Yale L.J. 1363 (1973)..................... 38

C. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine: From Recep

tive Passivity to Positive Action (1977)................ 3,

20, 21

Overbea, Why Statistics of Growth Don’t Tell Every

thing About Blades’ Enrollment in College, Chris

tian Science Monitor, March 21,1977 ................... 21

Poliak, Securing Liberty Through Litigation—The

Proper Role of the United States Supreme Court,

36 Mod. L. Rev. 113 (1973) ................................. 38

Sandalow, Racial Preferences in Higher Education:

Political Responsibility and the Judicial Role, 42

IT. Chi. L. Rev. 653 (1975)..................................... 19

Transcript of Argument, United Jewish Organisa

tions of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996

(1977) .................................................................... 29

H.S. Bureau of Census, Statistical Abstract of the

United States (1974) ............................................ 19

J . Wellington & P. Gyorffy, Report of Survey and

Evaluation of Equal Education Opportunity in

Health Profession Schools (San Francisco: Uni

versity of California 1975)............................... 21

I n t h e

g’ttjtrme dour! nf % Initefc B u t zb

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R eg en ts of t h e U niv ersity of Ca lifo rn ia ,

P etitioner ,

X T 7

A llan B a k k e ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, HARVARD

UNIVERSITY, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

AND THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The institutions on whose behalf this brief is submitted

are private universities of a particular kind. They are in

stitutions which differ in geography and history, in size, in

resources, and in structure; but they are united by a prin

ciple which transcends their differences—namely, that the

governing standard for establishing and maintaining class-

2

room and research functions alike is, not quantity or multi

plicity, but excellence. Underlying this principle is the

conviction that a university’s highest function is to give

people of great talent and motivation the opportunity to

participate, as students and as teachers, in rigorous in

tellectual training and equally rigorous intellectual inquiry

—and thereby simultaneously to enlarge today’s corpus

of knowledge and creative works, and to develop tomor

row’s cohorts of physicians and poets, physicists and plan

ners, philosophers and politicians.

In pursuing this function and these goals, colleges and

universities, with rare exceptions, historically have been

accorded freedom from external influence and intrusion.

Our society has recognized that higher education can

flourish only so long as educators have substantial inde

pendence to formulate and implement the policies by which

it is transmitted.1 This freedom is not unfettered, and it

entails an equal measure of responsibility. When, however,

the problem is central to the educational process as is the

determination of the qualifications of students, when edu

cators are searching in good faith for solutions, and when

applicable legal norms are in doubt, we believe that the

cause of education, and hence the welfare of our society,

are best served by judicial restraint.

Un our view, it does not matter for the resolution of the issues

in this case whether the Regents and officers of the University of

California take a major part in shaping the admissions policies of

particular schools or delegate effective authority to the faculties of the

several schools. But we would advise the Court that in our institu

tions faculties have the dominant role in shaping admissions policies.

This brief speaks for our institutions as such—not for faculty mem

bers collectively or individually. Among other things, we seek in

this brief to preserve the substantial independence of our faculties,

including the freedom to adopt admissions policies different from

those we here defend. (Four of the lawyers whose names appear on

this brief are deans of the law schools of the amici institutions, and

as such have some oversight responsibility for admissions processes;

however, they sign this brief not in their decanal capacities, nor as

representatives of their faculties, but as individual lawyers.)

Up to about a decade ago, it was the fact (not designedly,

but the fact nonetheless) that the student bodies of the

amici institutions were overwhelmingly white,2 and their

faculties almost exclusively so. Belatedly, these institutions

•—like many other colleges and universities—recognized

that they were disserving their educational goals in two

important ways: (1) By not enrolling minority students

in significant numbers, the amici were continuing to deny

intellectual house room, to a broad spectrum of diverse

cultural insights, thereby perpetuating a sort of white

myopia among students and faculty in many academic dis

ciplines—most particularly the professions, the social sci

ences and the humanities. (2) The amici were doing next to

nothing to enlarge the minute minority fraction (no more

than 1% in many fields) of the pool of persons with doc

toral-level graduate and professional training—the pool

from which the amici and comparable institutions draw

their faculties, and also the pool from which, increasingly,

local and national leaders in the public and private sectors

tend to be selected.

2The amici institutions were not unique in this regard. As of the

academic year 1955-56, there were only 761 black medical students

in the country. This figure rose slightly, to 771, by the 1961-62

academic year, but declined to 715 in 1963. Hutchins, Reitman &

Klaub, Minorities, Manpower, and Medicine, 42 J. Med. Educ. 809

(1967).

The entering class in medical schools for 1968-69 contained 266

black students, or 2.7% of the total first year enrollment; 3 Native

Americans, or 0.03%; 20 Mexican Americans, or 0.2%; and 3 Puerto

Rican students, or 0.03%. The 2.7% figure for blacks, small as it

is, is somewhat misleading, since fully half of these students were

enrolled at the predominantly black institutions of Howard and

Meharry. Thus, at any particular predominantly white institution,

the actual percentage of black students was likely to be significantly

smaller. Association of American Medical Colleges enrollment data,

cited in C. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine: From Receptive Pas

sivity to Positive Action 28-29 (Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation 1977).

4

It was to alleviate these serious educational deficiencies

in their training and research programs that the amici (and

numerous other colleges and universities) developed ad

missions programs designed to increase minority enroll

ment. Intensive recruitment of minority applicants could

not of itself begin to insure a genuinely diverse student

body in institutions as selective as the amici institutions.

Most of the schools in these institutions are highly selec

tive—i.e., there are so many more applicants than places

available; and, more important, the number of applicants

with a high probability of successful or indeed distin

guished academic performance so greatly exceeds the avail

able spaces—that admissions decisions based on racially

neutral criteria, which take no account of the educational

deficit under which America’s non-whites have labored

throughout our history, would not yield a large enough

number of minority students to achieve substantial di

versity. Thus, in choosing among a large number of clearly

qualified candidates for admission, these schools are seek

ing to achieve their educational goals through conscious

treatment of an applicant’s membership in a minority

racial group as a favorable factor in the consideration of

his application.8 The judgment and opinion of the Cali

fornia Supreme Court put the attainment of these goals in

jeopardy:

1. The narrow issue for decision in the instant case is

whether the medical school of a state university may not

only accord favorable consideration to minority applicants

3“ Racial group” and similar phrases are not used in this brief

with any pretense of scientific accuracy. When we refer to a racial

minority such as blacks we mean a group that is perceived as ‘ ‘ black ’ ’

by most Americans, and has suffered various forms of discrimination

and been isolated to some degree from social and cultural contact with

white Americans as a conseqence. In particular, no genetic connota

tions are intended. A large number of American blacks have some

white ancestors. Similar observations are appropriate with respect

to references to other racial minorities in this brief.

but for this purpose may also establish a special admissions

program limited to disadvantaged members of minority

racial groups, with the earmarking of 16 places in an enter

ing class of 100 for persons selected through that special

program. The decision of this Court may apply narrowly

only to a program of the precise kind employed at the

Medical School of the University of California at Davis.

But the implications of an affirmance of the decision of

the Supreme Court of California may threaten many other

more flexible types of admissions programs at the amici

institutions and similar colleges and universities. The

threat is perceived as especially serious in light of many

of the contentions and observations expressed in the ma

jority opinion of the California Supreme Court.

2. While the instant case involves a state university,

we are apprehensive that a judgment of affirmance by this

Court would threaten the continuation by private universi

ties of admissions policies that they believe to be educa

tionally vital.

a) Private as well as public universities have various

relationships, financial and otherwise, with federal and state

agencies. The standards for determining whether a given

degree of governmental involvement is sufficient to render

the Fourteenth Amendment applicable to otherwise private

activity have been pieced out by this Court on a case-by-case

basis. While courts have generally declined to apply the

Amendment to private universities, we cannot be certain

as to the ultimate disposition of this question.

b) A decision of this Court holding the admissions

program at Davis unconstitutional under the Fourteenth

Amendment might influence the construction of statutory

prohibitions against discrimination to which some or all

of the amici might be subject. These include Title VI of the

Civil Bights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000 (d) (1970), for

bidding discrimination in any program receiving federal

6

financial assistance; 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (1970), prohibiting

some forms of discrimination in willingness to enter into

contracts, including contracts to provide education; and a

number of state and local laws forbidding racial and other

discrimination in admissions by educational institutions.

3. Even if private universities are not legally con

strained in their freedom to pursue admissions policies that

they deem educationally most sound, they will be harmed

if public universities are denied similar freedom. Diversity

in background, including race, within faculties is important,

enriching the interchange of ideas and offering role models

to minority students. The pool of outstanding scholars and

teachers from which faculties are selected is fed by gradu

ates of both private and state universities. To dry up a

major potential source of minority faculty members—

minority applicants not admitted to state institutions be

cause their exceptional talents had not yet manifested

themselves when they applied for admission—would make

achievement of the faculty recruitment objectives of all

universities more difficult.

4. If state universities are forbidden to consider race

in admissions, private universities, even if free of similar

legal constraints, would face uncomfortable choices. It

might be felt that programs held by this Court to violate

the Fourteenth Amendment if undertaken by state schools

could not be pursued in good conscience by private univer

sities. Others might argue that pluralism in American so

ciety is sufficiently important that, so long as their actions

were not illegal, private universities should feel free to

adhere to their principles without regard to what might or

might not be permissible for state universities. A third point

of view might be that private universities should attempt

vastly to increase the number of minority students in order

to compensate for the restrictions imposed upon state uni

versities. We would greatly prefer to reach decisions on

7

admissions solely on educational considerations, undis

tracted by a debate likely to be divisive and destructive.

We hope that our experience and perspectives may be of

assistance to tbe Court in its treatment of tbe difficult ques

tions raised by tbis case.

Tbe following private universities have indicated their

general support for tbe arguments advanced in tbis brief

and join the amici in urging reversal of the judgment of

the California Supreme Court:

Brown University

Duke University

Georgetown University

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

University of Notre Dame

Vanderbilt University

Villanova University

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

When a university must choose among many more quali

fied applicants for admission than it can accept, choices are

made on the basis of educational objectives. Expected aca

demic performance is a significant criterion but only one

of several. There are important educational values in hav

ing a student body with diverse interests and backgrounds.

Such factors as extra-curricular activities, employment

experience, and geographical distribution have tradition

ally been taken into account, because a student body with

varied backgrounds and interests provides the most stimu

lating intellectual environment.

For the same reason, many universities regard member

ship in a minority race as a favorable factor to be con

sidered along with others in deciding whom to admit. The

differences in experience that arise out of growing up

black, or Chicano', or Puerto Rican, or Native American,

enable students who are members of those groups to intro

duce into the university community important perceptions

and understandings. An educational process enriched in

this way is not only of great importance to students: it

broadens the perspectives of teachers and thus tends to ex

pand the reach of the curriculum and the range of the

scholarly interests of the faculty.

Furthermore, by making conscious efforts to include

more minority students in their undergraduate and pro

fessional programs, universities are better performing the

function of providing tomorrow’s leaders in all walks of

life. If our pluralistic society is to achieve its objective of

increasing the number of minority doctors, judges, corpo

rate executives, university faculty members and govern

ment officials, universities must make available to qualified

minority students the opportunity to gain the necessary

education.

9

II.

The Supreme Court of California appears to acknowl

edge the constitutional propriety of selecting a racially

diverse student body. But the court has held that this

permissible end must be sought without taking race into

account—an anomalous circuity insisted upon in the belief,

unsupported by the record, that racially random processes

would somehow produce a student body of sufficient racial

diversity.

We appreciate the concerns which underlie the Cali

fornia court’s reluctance to sanction racially defined pro

cesses. But we disagree with the California court’s con

jecture—and it is only conjecture, flatly contradicted by

the only testimony of record—that universities can achieve

racially diverse student bodies without taking into account

the race of those applying for admission. Our institutions’

experience confirms that the substitute devices suggested

by the California court are incapable of fulfilling this con

stitutionally legitimate objective.

The principal alternative suggested was the establish

ment. of a larger program for the admission of the “ dis

advantaged,” regardless of race. But disadvantage—

whether predicated on cultural or economic criteria—is not

synonymous with membership in an ethnic minority. While

a disproportionate number of minority groiip members is

disadvantaged, most of the disadvantaged in this country

are white. To be sure, programs according favorable treat

ment to disadvantaged applicants may also serve important

educational purposes. If honestly administered, however,

and if disadvantage is not treated merely as a euphemism

for race, a program for the disadvantaged in lieu of a

program of similar scope for minorities would sharply

reduce the admission of minority applicants. In order to

ensure adequate representation of minority students, the

number of disadvantaged students admitted would have to

10

be so increased that the very diversity we are trying to

achieve would be destroyed, critical educational goals and

standards would be endangered, and the capacities of finan

cial aid programs for students would be overwhelmed.

Other alternatives propounded by the Supreme Court of

California would also he ineffective. Total abandonment

of attention to grade point averages and test scores would

deprive us of tools that are valuable in screening appli

cants and in comparing applicants of similar backgrounds;

in their absence the process of selection would he far more

difficult and undoubtedly less effective. The alternative of

quickly enlarging or adding to the number of medical

schools (or other graduate or undergraduate schools) is

politically and fiscally incredible and educationally un

sound; moreover, while it would presumably increase the

total number of minority students admitted it would not

enlarge their proportion in any school or class and thus

would not achieve the educational values afforded by di

versity in students’ racial backgrounds.

in.

Favorable treatment of minority group members in

university admissions is sharply different from discrimina

tion against minorities. It is in no way invidious, nor does

it work to the disadvantage of groups unable to protect

themselves in the political process. See San Antonio Inde

pendent School District v. Rodrigues, 411 U.S. 1, 28 (1973) ;

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152-

53 n. 4 (1938).

Educational policy is an area traditionally accorded,

and particularly appropriate for, judicial restraint. See

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodrigues, 411

U.S. at 42-43; Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 263

(1957) (concurring opinion). Needs and goals, as reflected

11

in admissions policies, vary from university to university

and among different schools in the same university. Educa

tors need substantial freedom to search for better solutions

to difficult educational problems, freedom denied by the kind

of judicial intervention practiced by the Supreme Court of

California.

Constitutional questions—particularly those of great

moment, as in the instant case—should not be decided in

the abstract but only in the context of a full factual record.

There was no such record in this case. The decision of the

California Supreme Court was based on assumptions of

fact not put to proof. On what that court thought to be the

critical issue, the availability of less restrictive alternative

means to attain concededly valid goals, its decision was

predicated solely on its own conjectures and ignored un-

contradieted testimony in the record to the contrary. The

decision of an important constitutional question involving-

momentous issues of educational policy should rest on

firmer foundations.

ARGUMENT

I. The Inclusion o f Qualified M inority Group M embers in a

Student Body Serves Im portant Educational Objectives.

At our institutions, as at many others, there are far

more applicants for admission than there are places in the

entering classes. The large majority of applicants are fully

qualified, as indicated by factors such as their grade point

averages and test scores, to perform successfully the aca

demic work that would be required of them should they

be admitted. The most difficult task of the admissions com

mittees is, therefore, to select from among these “ qualified”

applicants those who will be admitted.

In making this selection, colleges and universities can

apply a wide variety of criteria that will vary from in-

12

stitution to institution and even among schools within a

university. The choice of criteria will depend upon educa

tional objectives. In our institutions, particularly in the

selection of undergraduates, diversity in the student body

has been an important educational objective. In addition to

predicted academic performance, factors believed to con

tribute to diversity and strength of a student body, such

as geographical distribution, employment experience, musi

cal skills, extracurricular activities and travel, are all re

garded as legitimate and relevant, and usually taken into

account without controversy.4

Academic ability has not, therefore, been the sole cri

terion for selecting students at our institutions. In choos

ing among applicants qualified to do the academic work,

factors other than predicted academic performance may

well be determinative in reaching admissions decisions.

The ultimate question is which candidates from among the

“ qualified” pool will contribute most, in the context of an

entire class, to the achievement of the institution’s educa

tional objectives.5

A policy of increasing the number of students from

minority groups is, in our judgment, the best choice for all

of our students because it is the best way to achieve a di

verse student body. A primary value of liberal education

4Although some of our professional schools give great weight to

predicted academic performance and hence relatively less weight

than our undergraduate and other professional schools to the other

factors mentioned here, even in those schools elements of diversity

may he decisive in a limited but significant number of eases.

5Set forth in the Appendix to this brief is a description of the

criteria applied in selecting students for admission to Harvard

College, the rationale for the choice of these criteria, and some indica

tion of the relative weight given to different criteria, including

minority status, in particular admissions decisions. This description

applies generally to the selection of undergraduates at the other three

amici institutions.

13

should be exposure to new and provocative points of view,

at a time in the student’s life when be or she has recently

left home and is eager for new intellectual experiences.

Minority students add such points of view, both in the class

room and in the larger university community.

Just as diversity makes the university a better learning

environment for the student, so it makes the university a

better learning environment for the faculty member. The

university’s encouragement of variety in ideas is, to the

scholar, a most appealing aspect of academic life. It has

been the experience of many university teachers that the

insights provided by the participation of minority students

enrich the curriculum, broaden the teachers ’ scholarly inter

ests, and protect them from insensitivity to minority per

spectives. Teachers have come to count on the participa

tion of those students. Indeed, present faculty support for

admissions of more minority students stems in part from

an appreciation for past contributions, and from loyalty

to friendships with particular individual students whom

teachers might otherwise never have come to know.

Finally, there is an additional, related, yet independ

ently compelling, educational purpose served by enlarging

the universe of highly trained minority persons—namely,

diversifying the leadership of our pluralistic society. The

training of leaders has been a traditional and fundamental

educational responsibility and one which, with the matur

ing of our society, rests with special weight on colleges and

universities. As Chief Justice Vinson stated for this Court

in McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 339 IT.S. 637, 641 (1950), striking

down arbitrary constraints on a black graduate student’s

free interchange with white fellow students:

Our society grows increasingly complex, and our

need for trained leaders increases correspondingly.

Appellant’s case represents, perhaps, the epitome of

14

that need, for he is attempting to obtain an advanced

degree in education, to become, by definition, a leader

and trainer of others. Those who will come under Ms

guidance and influence must be directly affected by the

education he receives.

Today American colleges and universities are taking im

portant steps to meet the “ need for trained leaders” iden

tified by this Court twenty-seven years ago. It would be

quixotic—and tragic—for this Court now to find that the

Constitution prevents academic institutions from taking

those steps necessary and proper to fulfillment of an edu

cational responsibility so vital to the welfare of the nation.

By our admissions programs, we are not merely con

tributing to the cause of increasing the numbers of minority

leaders and public servants—although of course we wish

very much to do that. We are also broadening the percep

tions of our majority students, and we believe that this

will be reflected in qualities that they will retain for the

rest of their lives. A central function of the teacher is to

sow the seeds for the next generation of intellectual leaders,

and this, indeed, is a main reason why many university

instructors find that an ethnically diverse student body

helps them to fulfill their teaching roles. In short, we hope

that by these efforts, the leadership of the next generation—-

majority and minority members alike—will be the better,

the wiser and the more understanding.

II. Unless Race May Be Considered in Admissions Decisions,

Selective Institutions W ill Not Be Able to Achieve Ade

quately Diverse Student Bodies W hile Maintaining Other

Significant Educational Values.

The educational goals discussed above cannot be rea

lized by any racially neutral procedure known to us. The

problem, as we have previously noted, is simply this. Se

lective institutions such as ours receive applications from

15

many more persons than they have room for.6 Some of

those applicants are plainly not qualified for admission.

That is, it cannot he predicted with confidence by looking

at their test scores and prior academic performance that

they will survive in, much less contribute to, the academic

course they wish to pursue. Others, few in number, are so

exceptional, by reference to test scores, grades and prior

achievement, that their admission is a virtual certainty.

What remains then, from the original pool of applicants,

8For example, the number of applicants and matriculants at the

medical schools of the amici institutions for the classes entering in

1973-1976 were as follows:

1973 Applicants Matriculants

Columbia.................................... 3,789 147

Harvard .................................... 3,045 168

S tan fo rd .................................... 4,131 89

Pennsylvania ............................ 3,898 160

1974

Columbia.................................... 4,458 147

Harvard .................................... 3,258 165

S tan fo rd .................................... 4,553 94

Pennsylvania ............................ 4,124 160

1975

Columbia.................................... 5,042 147

Harvard .................................... 3,210 165

S tan fo rd .................................... 4,662 86

Pennsylvania............................ 4,895 160

1976

Columbia.................................. 4,927 148

Harvard .................................... 3,670 168

S tan fo rd ................................. 5,117 86

Pennsylvania ............................ 5,246 160

16

is a large number of applicants, still much larger than

the number of available spaces, who can, on the basis of

relevant predictors, successfully complete the academic

course of their choice. It is from this number that the

balance of the entering class must be selected.

The unfortunate fact of life in this country is that appli

cants who are members of minority groups tend, as a gen

eral matter, not to score as well as whites on the standard

ized tests to which reference is made in the admissions

process. We think it unnecessary to labor here the reasons

for this phenomenon. The educational deprivations which

minorities have suffered in this country are well known to

the Court.

Choosing from among the many who are qualified in

order to achieve, among other things, the racial and ethnic

diversity so important to our institutions, cannot be left

to chance. There are many ways to achieve diversity, per

haps as many as there are institutions and schools within

institutions which seek such diversity. It is, however, es

sential to any program designed to serve this end that race

be specifically considered in choosing a student body.

The California Supreme Court chose to ignore the in

formed views of the educators and suggested instead its

own strategies to reach what it conceded were legitimate

ends. Most prominently, it suggested that colleges and

universities accord preferential treatment to the “ disad

vantaged.” It also suggested as possible approaches more

aggressive recruiting, the abandonment of reference to

test scores and grade point averages, and finally, the ex

pansion of the size or number of educational institutions.

As we attempt to demonstrate below, these suggestions will

not work. If selective colleges and universities are forbid

den to give weight to the fact that an applicant is a member

of a racial minority group, there will almost certainly be an

abrupt decline in minority enrollments.

17

A. M inority Status Must Be Considered Independently of Eco

nomic or Cultural Deprivation.

The California Supreme Court has expressed the view

that the Davis Medical School’s present efforts to achieve

a racially mixed class are unconstitutional because there is

a less restrictive alternative—namely, admitting a larger

number of disadvantaged students without regard to their

race. However, criteria based on disadvantage which take

no account of race are useful only as a supplement to, and

not a substitute for, criteria based on race.

The California court does not define the term “ disad

vantage” explicitly, but it apparently intends to refer

to the Davis criteria having to do with the occupational

background and education of the student’s parents and

the family’s financial situation. But being disadvantaged

is not synonymous with being black, or Chicano, or Puerto

Rican, or Native American. While disproportionate num

bers of minority group members are economically disad

vantaged, the minority experience is distinct from the ex

perience of proverty. Growing up black—even middle-class

black—involves a whole range of different encounters,

perceptions, and reactions. To educate all students to deal

with the problems of the society that we have, rather than

the one we would like to have, we need the contribution of

those whose lives have been different because their race is

different.7 Indeed, our institutional needs for diversity

would be inadequately met if our minority students included

only those from depressed socioeconomic backgrounds.

7Minority students who are also poor are, in effect, doubly disad

vantaged. For, paradoxically, membership in a racial minority can

be considered a disadvantage in itself, even while it is a special

cultural and social experience which enriches minority individuals

and the university communities of which they become part. The

prevalent stereotyping of minority group membei’s, which can under

mine their academic aspirations and achievements early in life, and

the calamitous psychological effects of the continued de facto segre

gation of grade and high schools in this country, suggests that minor

ity applicants should receive particularly careful consideration quite

apart from any economic deprivation.

18

Moreover, since admissions programs that take account

of race many have other purposes than, or in addition to,

increasing the number of disadvantaged students, disad

vantage alone does not go far enough. We have noted that

disadvantage is not synonymous with membership in an

ethnic minority for the purpose of achieving our shared

goal of diversity in our student bodies. In addition, it

takes no cognizance of the purpose, to which many colleges

and universities subscribe, of providing minority youth with

role models, and it does not provide for the benefits only

minorities can bring to a profession. Insofar as admissions

programs are designed to improve society in any of these

ways, racially neutral criteria are beside the point.

The avowed end of the Davis Medical School is to in

crease the number of disadvantaged minority students in

its classes and not merely to adjust applicants’ test scores

to reflect better their purely academic qualifications. The

California Supreme Court assumes the constitutionality of

this end, but holds that the Medical School is constitution

ally prohibited from achieving it candidly; the court implies

instead that universities can bring minority admissions to

approximately the level they desire by adjusting the im

portance attached to various non-racial criteria which are

currently used, or might be used, in the admissions process.

We respectfully submit that this suggestion is based on

ignorance of the fact that adjustments honestly applied

cannot go far enough to accomplish concededly legitimate

purposes without endangering other critical institutional

goals. Alternatively, it is an invitation to colleges and uni

versities to do covertly what they have been forbidden to do

openly.

B. Use of a Racially Neutral Standard of “Disadvantage”

W ould Reduce the Number of M inority Matriculants.

Use of a racially neutral standard of disadvantage, as

urged by the California court, would reduce the number

19

of places open to minority applicants for admission to

American colleges and universities. This is so because

most Americans who are disadvantaged—most of the poor

and the culturally deprived—are white.8 Once a color-blind

preference for the disadvantaged was implemented white

students not currently applying to selective institutions

because of the unlikelihood of admission would presumably

apply, and qualify for admission, in much greater numbers.

If a preference for the disadvantaged were applied hon

estly, and not as a euphemism for a preference for minority

group members, the number of minority applicants ad

mitted would drop off sharply.

Theoretically, the number of disadvantaged admitted

could be increased, with the hope than an adequate number

of minority members would be picked up in the process.

It is difficult to calculate how large a fraction of each class

would have to be earmarked for the disadvantaged in order

to bring in a sufficient number of minority students to

achieve the goal of diversity, but in some schools it might

well absorb the entire class. A significant increase in the

number of spaces reserved for disadvantaged students

would almost surely endanger other critical educational

goals and standards. Moreover, there would be no way for

universities to support large numbers of disadvantaged

students through financial aid.9 The school would thus be

8In 1972, of a total of 24.5 million persons who were below the

poverty level established by the United States government, 16.2

million were white. U.S. Bureau of Census, Statistical Abstract of the

United States 389, Table No. 631 (1974). See also Sandalow, Racial

Preferences in Higher Education: Political Responsibility and the

Judicial Role, 42 U. Chi. L. Bev. 653, 690 (1975).

9This difficulty was noted in the dissenting opinion of the Cali

fornia Supreme Court. Bakke v. Regents of the Univ. of Gal., 18 Cal.

3d 34, 90, 553 P.2d 1152, 1190, 132 Cal. Bptr. 680, 718 (1976). See

also Sandalow, supra note 8, at 691.

The author of one study concludes that, due to the difficulties

minority students face in integrating themselves into a culturally

20

forced to choose between grossly inadequate aid for every

one admitted under the program—a rather hollow offer of

admission—or reserving to some portion of the disadvan

taged admittees a subsistence level of support, an effective

exclusion of most of the recruited students. And even if

sufficient financial aid were available, the very diversity

sought to be achieved would be defeated—all for the sake

of complying with the apparent conclusion of the California

Supreme Court that it is proper for an educational institu

tion to take measures for the purpose of increasing minor

ity admissions as long as it uses indirect means to do so.

“ Seeking out” disadvantaged students of high poten

tial, as suggested by the Supreme Court of California,

might increase slightly the number of such minority persons

who apply. Again, unless the search were part of a program

that included favorable weight to minority status, the end

result would be an increase in white, not black or Chicano,

admissions.10 The California court seems unaware of the

fact that vigorous efforts to identify and recruit talented

minority students have been made by almost all selective

schools for about a decade and that more intensified efforts

alien environment, financial burdens fall more heavily on them than

on their economically disadvantaged majority counterparts. M.

Miskel, Minority Student Enrollment, Research Currents, Nov. 1973,

at 3 (ERIC Clearing House on Higher Education). See also C. Ode-

gaard, Minorities in Medicine: From Receptive Passivity to Positive

Action 63-65 (Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation 1977). Ironically, the

pressure to increase special admissions to include all economically

disadvantaged comes just at a time when general economic condi

tions and decreased government spending threaten even the limited

programs presently in existence. B. Caress & J. Kossy, The Myth of

Reverse Discrimination: Declining Minority Enrollment in New

York City’s Medical Schools 6 (Health Policy Advisory Center,

Inc. 1977). A related problem is the cost of providing remedial edu

cation for admitted students with deprived educational backgrounds.

Odegaard, supra at 126.

10The same would be true of the court’s proposal that remedial

schooling be provided for disadvantaged students of all races.

21

are not likely to have muck incremental effect.11 Indeed,

after a certain point the process tends to become a com

petitive one in which a number of schools all attempt to

woo the most promising minority students, rather than add

ing substantially to the pool of such students to be consid

ered for admission.12 Even when combined with vigorous

reci’uitment efforts, consideration of disadvantage is no

answer to the problems the Davis admissions program

sought to solve. Moreover, it seems likely to us that this

alternative, like most of the others suggested by the Cali-

1:lEvery one of the 89 medical schools sampled in one survey under

taken for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare engaged

in minority recruitment activities. J. Wellington & P. Gyorffy, Report

of Survey and Evaluation of Equal Education Opportunity in

Health Profession Schools (San Francisco: University of California

1975), quoted in C. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine: From Recep

tive Passivity to Positive Action 99 (Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation

1977). In addition, the American Association of Medical Colleges

has since 1970 administered a Medical Minority Applicant Registry

to assist schools in their recruitment efforts. Odegaard, supra, at 108.

Similar programs exist to assist minority students’ entrance into

college.

One reason that increased recruitment is not likely to have much

effect is that proportionately fewer blacks and other minority group

members graduate from four-year colleges of the sort that have

traditionally supplied medical schools. Relatively large numbers

are concentrated in two-year community colleges. Overbea, Why

Statistics of Growth Don’t Tell Everything about Blacks’ Enroll

ment in College, Christian Science Monitor, March 21, 1977, at 26,

col. 1; Brown & Stent, Black College Undergraduates, Enrollment

and, Earned Degrees, 6 J. Black Stud. 5,10 (1975). In addition, with

the exception of Asian-Americans, fewer graduate in fields such as

biochemistry and life sciences, which provide the background neces

sary for medical school. Educational Testing Service, Graduate

and Professional School Opportunities for Minority Students 4 (6th

ed. 1975-77, Princeton); Atelsek & Gomberg, Bachelors Degrees

Awarded to Minority Students, 1973-1974, at 8 (Higher Educ. Panel

Rep., No. 24, American Council on Education, January 1977).

12See C. Odegaard, Minorities in Medicine: From Receptive Pas

sivity to Positive Action 100 (Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation 1977);

Knauss, Developing a Representative Legal Profession, 62 A.B.A.

J. 591, 593 (May 1976).

22

fornia Supreme Court, which are discussed below, would,

if implemented, diminish the number of spaces available to

respondent and to others similarly situated.

C. Other Alternatives Suggested by the Suprem e Court of Cali

fornia W ould Also Be Ineffective.

The other alternatives suggested by the California Su

preme Court have even less potential. One suggestion

was to dispense with numerical criteria completely, and

abandon use of test scores and grade point averages. How

ever, with all of their shortcomings, these yardsticks are

not irrelevant: when used with restraint and discretion we

have found them valuable tools in measuring the probable

academic performance of applicants.13 Test scores and

grade point averages help to define the universe of those

qualified to do creditable and rewarding work in highly

selective academic institutions, and they furnish clues as

to those individuals among' the qualified group who will

gain the most from, and contribute the most to, academic

opportunities which must be rationed among a limited num

ber. That is the substantial utility of these numerical in

dicators.14

Total abandonment of numerical standards would result

in giving too much weight to such subjective and manipu-

lable factors as personal recommendations and statements

of career goals; for some it would constitute an invitation

to invidious discrimination. Academic quality would un

doubtedly deteriorate, yet without any assurance that an

adequate level of minority admissions could be maintained.

iaSee, e.g., A. Carlson & C. Werts, Relationships Among Law

School Predictors, Laiv School Performance and Bar Examination

Results (E.T.S. 1976); Law School Admission Council, Law School

Admission Bulletin 1976-1977 (E.T.S.).

14-VVe think it appropriate to add that we know of no empirical

demonstration that there is a direct correlation, although our intui

tion suggests that there is a correlation, between academic perform

ance at such institutions and ultimate career “ success,” however

success may be defined.

23

Finally, from a purely administrative point of view, even

well-endowed colleges and universities such as amici can ill

afford the substantial diversion of resources to vastly en

larged admissions staffs which abandonment of numerical

admissions criteria would require, at least when the benefits

are so doubtful and the economic horizon is so bleak.

The Supreme Court of California also suggests that a

less restrictive means for enlarging minority admissions

would be to increase the size or number of medical schools.

It seems unrealistic in the extreme to assume that there

would or could be a nationwide or statewide jump in the

number of selective schools, medical or otherwise, or in the

size of those existing. Quite apart from the staggering

costs involved, new institutions of outstanding quality

cannot be l'olled off an assembly line overnight, nor can

existing schools be dramatically expanded in size without

severe adverse effects on instruction and scholarship. More

over, if America’s enormous and growing investment in

higher education is to continue to be responsibly adminis

tered, the aggregate number of persons trained in medicine

and other disciplines must turn on the nation’s aggregate

needs. In contrast, the California court’s casual approach

would require a major reallocation of resources not to train

needed professionals but to accommodate those large num

bers of disadvantaged persons only a fraction of whom

would constitute the minority student population whose

advanced training is of priority educational importance.15

In short, the less restrictive means for increasing minor

ity admissions that the Supreme Court of California said

1BIn recent years, for example, first year enrollment in U.S. medi

cal schools increased from 10,422 in 1969 to 15,295 in 1975—an in

crease of almost one half. In spite of vigorous recruitment efforts and

minority admissions programs, only 890 of the 4,873 added positions

went to minority students. B. Caress & J. Kossy, The Myth of Reverse

Discrimination: Declining Minority Enrollment in New York City’s

Medical Schools 5 (Health Policy Advisory Center, Inc. 1977).

24

were available, and on the basis of wbicb it held the pro

gram at Davis unconstitutional, seem to us, on examination,

illusory. Unlike our present admissions systems, which

preserve the dual goals of diversity and academic achieve

ment, each would fail either to enroll minority students in

sufficient numbers or to maintain our present standards

of excellence—or both. At least, most educators so con

clude. The contrary view of the California court rests, we

respectfully submit, on judicial conjecture—certainly not

on facts of record, nor on inferences properly drawn from

patterns of university experience of which a court might

reasonably take judicial notice.

The only evidence in the record on the subject was the

uncontradicted declaration of Dr. George H. Lowery, Asso

ciate Dean and Chairman of the Admissions Committee at

Davis Medical School, that his “ experience as Chairman

of the Admissions Committee has convinced [him] that

there would be few, if any, Black students and few Mexican-

Americans, Indians, or Orientals from disadvantaged back

grounds in the Davis Medical School, or any other medical

school, if the special admissions program and similar pro

grams at other schools did not exist.” (R. 67-68).

The experience of our own institutions both reinforces

the judgment of Dr. Lowery that programs taking minor

ity status into account in admissions are necessary, and

suggests that the alternatives posited by the Supreme Court

of California are entirely unrealistic.

III. The Judgment of the Suprem e Court of California Should

Be Reversed.

The guiding principle of freedom under which American

colleges and universities have grown to greatness is that

these institutions are expected to assume and exercise

25

responsibility for the shaping of academic policy without

extramural intervention. A subordinate corollary princi

ple-critical for this case—is that deciding who shall be

selected for admission to degree candidacy is an integral

aspect of academic policy-making. The linked principles

emerge clearly from the moving manifesto—relied upon

by Mr. Justice Frankfurter twenty years ago—of distin

guished educators who were vainly seeking to preserve

their country’s vanishing academic freedom, to wit, the

embattled senior scholars of the University of Cape Town

and the University of Witwatersrand:

. . . It is the business of a university to provide that

atmosphere which is most conducive to speculation,

experiment and creation. It is an atmosphere in which

there prevail “ the four essential freedoms” of a uni

versity—to determine for itself on academic grounds

who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be

taught, and who may be admitted to study.16

The fact that academic institutions are within the ambit of

the First Amendment does not mean that they are immune

from the law’s norms. Indeed, when academic institutions

have pursued admissions policies the antithesis of the policy

challenged here, this Court has properly brought them to

book. Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ; Missouri ex

rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938). But the

rarity of instances of judicial intervention in academic

affairs proves the rule that governmental displacement of

the authority of those primarily vested with academic

responsibility is contrary to our traditions. Were it other

wise, as Mr. Webster put it in the memorable argument

16Quoted by the Justice in his concurring opinion in Sweezy v. New

Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 263 (1957), in which Mr. Justice Harlan

joined.

26

which prevailed in this Court in the Dartmouth College

case,17

learned men will be deterred from devoting themselves

to the service of such institutions, from the precarious

title of their offices. Colleges and halls will be deserted

by all better spirits, and become a theater for the con

tention of politics. Party and faction will be cherished

in the places consecrated to piety and learning. These

consequences are neither remote nor possible only. They

are certain and immediate.

Nor are the principles of academic freedom protective only

of private institutions, such as the amici. These principles

likewise safeguard the integrity of public institutions, wffien

they or those who are their members are threatened by

unwarranted external intrusions. See Sweezy v. New

Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 262-63 (1957); of. Hamilton v.

Regents of University of California, 293 U.S. 245 (1934).

In undertaking to circumscribe the informed and good

faith discretion of those vested with authority to determine

the admissions policies of the Medical School of the Uni

versity of California at Davis, the California Supreme

Court has trenched upon the freedom of that School to

determine for itself crucial questions of academic policy.

Moreover, this judicial intrusion has been based upon a con

stitutional ruling which, with all respect, we believe to be pal

pably inadequate to the several substantial issues presented

by this litigation. As we have argued above, we think that

implementation of the California Supreme Court’s judg

ment will predictably preclude the achievement in this cen

tury of educational goals of great moment to which hun

dreds of American colleges and universities are committed.

17Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 4 Wheat. 518, 599

(1819).

27

We argue below that the court’s explanation of its judg

ment is doctrinally unpersuasive.

As we have demonstrated, the admissions process has

never been entirely impersonal, quantifiable, or “ objec

tive.” What distinguishes this case from all the non-cases

that have seldom been thought worth litigating is that the

additional element taken into account here is race.

Special treatment based on race touches sensitive nerves.

But the reason for this is the long tragic history of attention

to race for the purpose of discriminating against blacks

and other minorities. The problem of admissions programs

designed to augment the number of minority students in

volves delicate issues.18 But it is not the same as discrim

ination against minorities, and no amount of rhetoric can

make it the same.

The purpose of the special treatment of minorities in

university admissions, at Davis as elsewhere, is not to dis

criminate against majority applicants. Indeed, the purpose

is not only or even primarily to confer benefits upon mem

bers of minorities; where the principal goals are to improve

the quality of teaching and learning for majority as well as

18The special admissions program at Davis set aside 16 places in

a class of 100 for disadvantaged members of minority groups. Al

though we question the wisdom of this aspect of the Davis program,

we are not persuaded that such a program is unconstitutional. The

choice at Davis was only among, and the designated spaces would

only be filled by, qualified applicants, and the percentage of places

earmarked for minority members was smaller than their share of the

state’s population; in this context, designation of a precise number

of places may be a reasonable way of ensuring that enough minority

applicants are admitted to provide sufficient diversity in the student

body.

If, nevertheless, the procedure at Davis should be held uncon

stitutional, we would urge the Court to limit its decision to that

particular technique and to the facts and circumstances pertaining

at Davis rather than cast into doubt the wide variety of other more

flexible approaches designed to produce truly diverse student bodies.

28

minority students and to diversify this nation’s leadership,

the fact that there may be a consequential difference in the

effect on different races does not constitute invidious or

stigmatic discrimination.19

The use of race as a touchstone for governmental action

has been upheld in a number of contexts. Racial residential

patterns may, and indeed in some cases must, be considered

in the assignment of students to schools20 and in the use of

such remedial measures as busing.21 The use of similar data

in delineating legislative districts has also been upheld.22

Specific attention to race has been permitted, and often

required, to achieve equality in employment opportunity.23

As stated by the United States Court of Appeals for the

,9In fact, a recent study points out that in every year subsequent

to adoption of minority admissions policies by medical schools, the

number of spaces available for white applicants has increased. The

reason cited is an overall expansion of medical enrollments, of which

nonminority students have been the overwhelming beneficiaries.

Thus, while “ [a] persistent rumor, abetted by recent reverse discrim

ination law suits, holds that middle class sons cannot get into medical

school because of preferential treatment accorded minority appli

cants . . . [t]he facts simply do not support the case.” B. Caress & J.

Kossy, The Myth of Reverse Discrimination: Declining Minority

Enrollment in New York City’s Medical Schools 1 (Health Policy

Advisory Center, Inc. 1977).

A similar situation exists in undergraduate admissions, where

minority gains have not kept pace with the increase in white enroll

ment. Brown, Minority Enrollment and Representation in Institu

tions of Higher Education 2 (Ford Foundation Report by Urban Ed

Inc. 1974). ’

20E.g., Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1,

29-31 (1971); North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann 402

U.S.43 (1971).

21E.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971).

22United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v Carev 97

S.Ct. 996 (1977).

2SE.g.. United States v. Wood, Wire & Metal Lathers Local

46, 471 F.2d 408 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) •

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied,

406 U.S. 950 (1972); Contractors Ass’n of E. Pa. v. Secretary of

Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971).

29

First Circuit, “ our society cannot be completely color

blind in the short term if we are to have a colorblind society

in the long term.”24 And this Court has unanimously sus

tained a systematic official preference for tribal Native

Americans in the allocation of employment opportunities

in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Morton v. Mancari, 417

U.S. 535 (1974). The unique history and constitutional

status of Native Americans, of which this Court properly

took account in that case, are surely no more compelling

than the unique history and constitutional status of those

for whom the Civil War Amendments were written and

ratified.

Analogies may also be found in areas other than race,

such as sex discrimination, where this Court has upheld

favorable treatment of a class because it had previously

been discriminated against. Califano v. Webster, 97 S. Ct.

1192 (1977); Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 U.S. 498 (1975);

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974).

In these cases and others, the courts have shown under

standing of the difficulties of legislators and administrators

faced with the problems of the real America of today with

all its blemishes, rather than conjuring up rules for the

ideal, prejudice-free, society that we hope to attain. This

Court was certainly not cheered by its knowledge, in United

Jewish Organisations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 97

S. Ct. 996 (1977), that voters tend to choose candidates of

their own races, but it recognized the significance of this

fact in upholding the legislative districting there chal

lenged.26

24A ssocia ted Gen. C ontractors o f Mass. v. A ltsh u le r , 490 F.2d 9,

16 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974).

26In W illiam sburgh , counsel for petitioner, on oral argument,

challenged racial delineation of legislative districts in the following

terms: “ Race is not part of the political process. Race is an imper

missible standard__” T ra n scrip t o f A rg u m e n t, at 33. Mr. Robert H.

Bork, the then Solicitor General, responded: ‘ ‘ And I was astounded

30

Interestingly, the Supreme Court of California seems

to accept at least some of these realities. It assumed argu

endo that admitting a significant number of minority stu

dents served a compelling state interest. Unfortunately,

it then embarked on a dead-ended detour in which it con

tended that the Medical School at Davis should have

achieved its purpose of increasing the number of minority

students through the use of devices that purported to be

doing something else (and which, as shown above, would

have been ineffective, disingenuous, or both).

It has been the experience of the amici, as we believe

it has been that of most educational institutions, that the

remedies for the problems resulting from a long history

of racial discrimination are elusive. The hopes induced by

Brown v. Board of Education26 in 1954, that within a gen

eration racial inequalities in educational opportunity and

achievement would be eradicated, have not been realized.

Universities need some elbow-room in which to experiment

in their quest for solutions. This Court recognized the in

tractability of the problem of preventing racial discrimina

tion in voting when it upheld the use of extraordinary

when Mr. Lewin said that race is not a part of our political process.

Race has been the political issue in this country since it was founded.

And we may regret that that is a political reality, but it is a reality,

th a t’s what the Fifteenth Amendment is about, what the Civil War

was about, i t ’s what the Constitution was in part about, and i t ’s a

subject we struggle with politically today. ’ ’ Id., at 62.

We recognize, and indeed we are profoundly sympathetic with,

the concerns underlying the Chief Justice’s dissent, and Mr. Justice

Brennan’s concurrence, in Williamshurgh. We believe that the

limited use of race for which we here contend is respectful of those

concerns. Race is, as Mr. Bork argued, “ a reality” which is central

to our history. Avoidance of reality is not conducive to sound con

struction of the Constitution. What the Constitution requires is

that majorities not use their power to injure or degrade minorities.

That constitutional infirmity does not inhere in this case.

26347 IJ.S. 483 (1954).

31

measures to cope with it in South Carolina v. Katzenbach.-7

A similar response is urgently needed here.

This case would seem to be particularly appropriate for

the exercise of judicial restraint. The policy questions are

difficult, and conscientious educators are dealing with them

to the best of their abilities, undoubtedly making mistakes

but learning as they do, always with the goal of improving

the instructional and scholarly quality of their institutions.

Presumptions of constitutionality, which should always

weigh heavily with this Court, are reinforced by consider

ations of federalism where states are severally striving for

answers, and further reinforced where the Court is being

asked to substitute its judgment for that of educators.

In San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1, 42 (1973), educational policy was described as

an “ area in which this Court’s lack of specialized knowledge

and experience counsels against premature interference

with the informed judgments made at state and local levels.

Education, perhaps even more than welfare assistance,

presents a myriad of ‘intractable economic, social, and even

philosophical problems.’ ” The problems of racial ine

quality involved in the instant ease are certainly no less

intractable than those of financial inequality that the Court

was considering in Rodrigues. Equally applicable here is

the Court’s further statement in Rodriguez (Id. at 43) :

The ultimate wisdom as to these and related problems

of education is not likely to be divined for all time even

by the scholars who now so earnestly debate the issues.

In such circumstances, the judiciary is well advised to

refrain from imposing on the States inflexible constitu

tional restraints that could circumscribe or handicap

the continued research and experimentation so vital to

finding even partial solutions to educational problems

and to keeping abreast of ever-changing conditions.

27383 U.S. 301 (1966).

32

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971), this Court declared:

School authorities are traditionally charged with

broad power to formulate and implement educational

policy and might well conclude, for example, that in

order to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society

each school should have a prescribed ratio of Negro to

white students reflecting the proportion for the district

as a whole. To do this as an educational policy is

within the broad discretionary powers of school

authorities . . . .

Is such discretion appropriate only for elementary and

high school authorities, but barred to educators at colleges

and graduate schools ?

The educational and other values relevant to admissions

policy vary from state to state, from university to uni

versity, and even among schools in the same university.

For example, a liberal arts college or a law school, where

a large measure of verbal interchange among students is

vital to the educational process, might attach more im

portance to diversification of background among the student

body than would an engineering school. A Hispanic lan

guage background might be more important in terms of

post-graduation community service in law or medicine than

in fields in which oral communication is less important.

Such questions of educational policy are therefore neces

sarily difficult, complex, and inherently not susceptible of

simple answers universally applicable. Educators need to

be free to make decisions reflecting their professional judg

ments concerning these values, not subject to the restraints

of a judicially imposed strait jacket.28

28As universities, and particularly private universities, we have