Michigan Road Builders v. Millikan Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

November 25, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Michigan Road Builders v. Millikan Court Opinion, 1987. e0ea19a0-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96455f00-5f36-4015-bfbd-80ff7c2a8f4d/michigan-road-builders-v-millikan-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

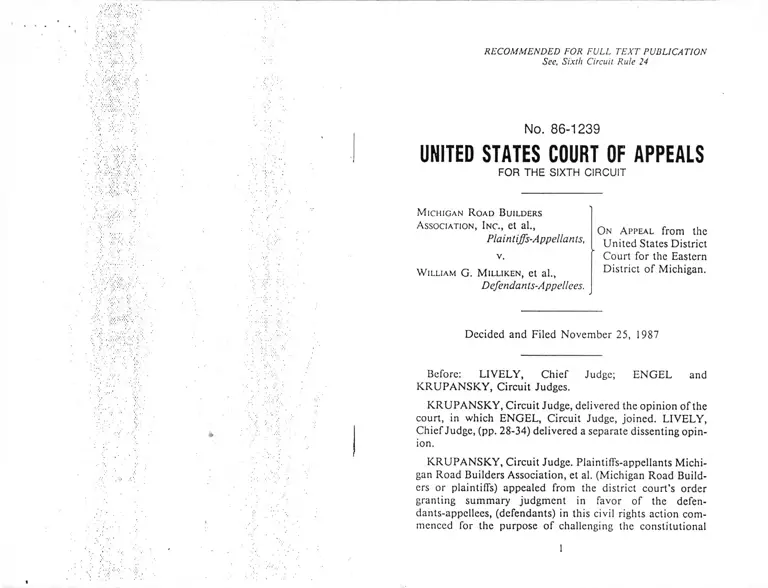

RECOMMENDED FOR FULL TEXT PUBLICATION

See, Sixth Circuit Rule 24

No. 86-1239

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

M ichigan Road Builders

Association, Inc., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

W illiam G. M illiken, ct al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

O n A ppeal from the

United States District

Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan.

Decided and Filed November 25, 1987

Before: LIVELY, Chief Judge; ENGEL and

KRUPANSKY, Circuit Judges.

KRUPANSKY, Circuit Judge, delivered the opinion of the

court, in which ENGEL, Circuit Judge, joined. LIVELY,

Chief Judge, (pp. 28-34) delivered a separate dissenting opin

ion.

KRUPANSKY, Circuit Judge. Plaintiffs-appellants Michi

gan Road Builders Association, et al. (Michigan Road Build

ers or plaintiffs) appealed from the district court’s order

granting summary judgment in favor of the defen-

dants-appellees, (defendants) in this civil rights action com

menced for the purpose of challenging the constitutional

1

validity of 1980 Mich. Pub. Acts 428 (Public Act 428), Mich.

Comp. Laws §450.771, el sec/.1 In particular, the Michigan

Road Builders charge that Public Act 428 which “set aside”

a portion of state contracts for minority owned businesses

(MBEs) and woman owned businesses (WBEs) impinges

upon the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution. Section 2 of Public Act 428, Mich.

Comp. Laws §450.772 provides that after the 1984-85 fiscal

year, each state department must award not less than 7% of

its expenditures for construction, goods, and services to

MBEs and not less than 5% to WBEs.2 Under Public Act 428,

2 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken. el al. No. 86-1239

lPlaintifTs-appellants “are (1) several non-profit associations whose

members arc, in general, construction firms, contractors and suppliers,

who have done, or are doing business with the Slate of Michigan, and

(2) various profit corporations who have had, or seek, contracts with

the State of Michigan.” Michigan Road Builders Ass'n v. Milliken, 571

F. Supp. 173, 174 (E.D. Mich. 1983). Dcfcndants-appcllccs arc William

G. Milliken, the former Governor of Michigan, the Michigan Depart

ment of Management and Budget, Gerald H. Miller, the former Direc

tor of the Michigan Department of Management and Budget, the Mich

igan Department ofTransportalion, and John P. Woodford, the former

Director of the Michigan Department ofTransportalion.

2Mich. Comp. Laws § 450.772 provides:

Sec. 2. (1) The construction, goods, and services procurement

policy for each department shall provide for the following per

centage of expenditures to be awarded to minority owned and

women owned businesses by each department except as pro

vided in subsection (6):

(a) For minority owned business, the goal for 1980-8 1 shall

be 150% of the actual expenditures for 1979-80, the goal for

1981-82 shall be 200% of the actual expenditures for 1980-81,

the goal for 1982-83 shall be 200% of the actual expenditures

for 1981-82, the goal for 1983-84 shall be 1 16% of the actual

expenditures for 1982-83, and this level of efiort at not less

than 7% of expenditures shall be maintained thereafter.

(b) For woman owned business, the goal for 1980-81 shall

be 150% of the actual expenditures for 1979-80, the goal for

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, et al. 3

a “minority” is a “person who is black, hispanic, oriental,

cskimo, or an American Indian,” Mich. Comp. Laws

§ 450.771 (c), and a “minority owned business” is “a business

enterprise of which more than 50% of the voting shares or

interest in the business is owned, controlled, and operated

by individuals who are members of a minority and with

respect to which more than 50% of the net profit or loss attrib

utable to the business accrues to shareholders who are mem

bers of a minority.” Mich. Comp. Laws §450.771(0- A

“woman owned business” is “a business of which more than

1981-82 shall be 200% of the actual expenditures for 1980-81,

the goal for 1982-83 shall be 200% of the actual expenditures

for 1981-82, the goal for 1983-84 shall be 200% of the actual

expenditures for 1982-83, the goal for 1984-85 shall be 140%

of the expenditures for 1983-84, and this level of effort at not

less than 5% of expenditures shall be maintained thereafter.

(2) If the first year goals arc not achieved, the governor shall

recommend to the legislature changes in programs to assist

minority and woman owned businesses.

(3) Each department, to assist in meeting the construction,

goods, and services procurement expenditures percentages set

forth in subsection (1), shall include provisions for the acco

modation of subcontracts and joint ventures. The provisions

shall be established by the governor and shall require a bidder

to indicate the extent of minority owned or women owned

business participation.

(4) Only the portion of a prime contract that reflects minority

owned or women owned business participation shall be con

sidered in meeting the requirements of subsection (1).

(5) Minority owned or woman owned businesses shall com

ply with the same requirements expected of other bidders

including, but not limited to, being adequately bonded.

(6) If the bidders for any contract do not include a qualified

minority owned and operated or woman owned and operated

business, the contract shall be awarded to the lowest bidder

otherwise qualified to perform the contract.

50% of the voting shares or interest in the business is owned,

controlled, and operated by women and with respect to which

more than 50% of the net profit or loss attributable to the

business accrues to the women shareholders.” Mich. Comp.

Laws §450.7710).

The Michigan Road Builders commenced the present

action on July 8, 1981 in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan seeking declaratory and

injunctive relief against the enforcement of the set-aside pro

visions of Public Act 428. In particular, the plaintiffs charged

that the set-aside provisions of Public Act 428 violated the

Ecjual Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as

well as 42 U.S.C. §§§1981, 1983 and 2000d,3 by according

4 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el at. No. 86-1239

342 U.S.C. § 1981 provides:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have

the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce con

tracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and properly

as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment,

pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to

no other.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 provides:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom, or usage, of any Stale or Territory or the

District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdic

tion thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be lia

ble to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or

other proper proceeding for redress. For the purposes of this

section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the Dis

trict of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the

District of Columbia.

42 U.S.C. § 2000d provides:

No person in the United Slates shall, on the ground of race,

color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in,

racial and ethnic minorities and women a preference in com

peting for state expenditures. After discovery had been com

pleted, the parties filed cross motions for summary judgment,

and on August 12, 1983, the district court determined that

Public Act 428 did not violate the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment and granted defendants’

motion for summary judgment. Michigan Road Builders

Ass'n v. Milliken, 571 F.Supp. 173 (E.D. Mich. 1983). Michi

gan Road Builders appealed, and this court dismissed the

appeal because the district court had not decided all of the

claims against the Michigan Department of Transportation.

Michigan Road Builders Ass’n v. Milliken, 742 F.2d 1456 (6th

Cir. 1984). Thereafter, the district court entered an order dis

posing of the remaining charges against the Department of

Transportation, Michigan Road Builders Ass’n v. Milliken,

654 F.Supp. 3 (E.D. Mich. 1986), and the Michigan Road

Builders commenced this timely appeal. On appeal, the plain

tiffs argued that the district court applied the incorrect legal

standard to determine the constitutional validity of Public

Act 428.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 5

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination

under any program or activity receiving Federal financial

assistance.

Because the protections afforded by these sections are coextensive with

the protections afforded by the Equal Protection Clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, Regents ofUniv. o f Calif, v. Dakke, 438 U.S. 265,

287, 333, 98 S.Ct. 2733, 2746, 2770, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978)(§ 1983

and 2000d); Detroit Police Officers' Ass'n v. Young, 608 F.2d 671,

691-92 (6th Cir. 1979) (§ 1981), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 938, 101 S.Ct.

3079, 69 L.Ed.2d 951 (1981), this court need only analyze Public Act

428 under Fourteenth Amendment equal protection standards. See

Associated Gen. Contractors o f Cal. v. Citv & County o f San Francisco,

813 F.2d 922, 928 n. 11 (9th Cir. 1987). Plaintiffs also alleged in their

complaint that Public Act 428 violated Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c et seq. See Johnson v. Transportation

Agency, 107 S.Ct. 1442, 1446 n.2, 94 L.Ed.2d 615 (1987)(suggcsting

that Title VII analysis differs from constitutional equal protection anal

ysis). They have abandoned this argument on appeal.

6 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, ct at. No. 86-1239

In addressing equal protection claims, the Supreme Court

has employed differing levels of judicial review depending

upon the type of imposed classification under constitutional

attack.4 “Racial and ethnic distinctions of any sort arc inher

ently suspect and thus call for the most exacting judicial

examination.” Regents o f Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke. 438 U.S.

265, 291,98 S.Ct. 2733, 2748, 57 L.Ed.2d 750 (1978)(plural-

ity opinion)(concluding that state medical school’s admission

program which reserved a specified number of student posi

tions for racial and ethnic minority applicants violated the

Equal Protection Clause). This “most exacting judicial

examination” has been labeled by the Supreme Court as

“strict scrutiny.” Id. at 287, 98 S.Ct. at 2747 (plurality opin

ion).

When a classification denies an individual opportu

nities or benefits enjoyed by others solely because

of his race or ethnic background, it must be regarded

as suspect.

4In considering equal protection claims, courts must first determine

whether the governmental body imposing the classification at issue had

authority to act to accomplish its purpose. Fullilove v. Klutznik, 448

U.S. 448, 473, 100 S.Ct. 2758, 2772, 65 L.Ed.2d 902 (1980) (plurality

opinion); Associated Gen. Contractors o f Cal., 813 F.2d at 928. In the

case at bar, the state asserted, and the plaintifTs did not dispute, that

Public Act 428 was designed to ameliorate the effects of past discrimi

nation against minorities and women competing for contracts to supply

the state with goods and services. It is beyond contention that a stale

legislature has the prerogative and even the “constitutional duly to take

affirmative steps to eliminate the continuing effects of past unconstitu

tional discrimination.” Wyganl v. Jackson Bd. ofEduc.. 476 U.S. 267,

106 S.Ct. 1842, 1856, 90 L.Ed.2d 260 (1986) (O’Connor, J„ concur-

ring)(cmphasis in original); Ohio Contractors Ass'n v. Keip, 713 F.2d

167, 172-73 (6th Cir. 1983); Associated Gen. Contractors o f Cal., 813

F.2d at 929. Accordingly, it is not disputed that the Michigan legisla

ture had jurisdiction to act for the purpose of ameliorating the effects

of past discrimination.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, ct al. 7

* * *

We have held that in “order to justify the use of

a suspect classification, a Stale must show that its

purpose or interest is both constitutionally permissi

ble and substantial, and that its use of the classifica

tion is ‘necessary . . . to the accomplishment’ of its

purpose or the safeguarding of its interest.”

* * *

Preferring members of any one group for no reason

other than race or ethnic origin is discrimination for

its own sake. This the Constitution forbids.

Id. at 305-07, 98 S.Ct. at 2756-57 (plurality opinion)(citations

omitted).

In Fullilove v. Khtlznick, 448 U.S. 448, 100 S.Ct. 2758, 65

L.Ed.2d 902 (1980), the Supreme Court probed a congres-

sionally enacted affirmative action plan embodied in the Pub

lic Works Employment Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C. § 6701 el seq.

The constitutional attack in that case was lodged against the

“Minority Business Enterprise” set aside provision of the act,

§ 103(0(2), 42 U.S.C. § 6705(0(2), which required local gov

ernmental units receiving funds under public works programs

to use 10% of the funds to procure services or supplies from

MBEs. The court determined that “Congress had abundant

evidence from which it could conclude that minority busi

nesses have been denied effective participation in public con

tracting opportunities by procurement practices that perpetu

ated the effects of prior discrimination,” id. at 477-78, 100

S.Ct. at 2774, and that the set aside provision therein at issue

was “narrowly tailored to the achievement of [the] goal” of

ameliorating the effects of that past discrimination. Id. at 480,

100 S.Ct. at 2776. Justice Powell, author of the Bakke

opinion, concurred in the Court’s opinion and filed an opin

ion in which he stated:

8 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. No. 86-1239

Section 103(0(2) [of the Public Works Employment

Act of 1977] employs a racial classification that is

constitutionally prohibited unless it is a necessary

means of advancing a compelling governmental

interest.

★ ★ ★

The Equal Protection Clause, and the equal pro

tection component of the Due Process Clause of the

Fifth Amendment, demand that any governmental

distinction among groups must be justifiable. Differ

ent standards of review applied to different sorts of

classifications simply illustrate the principle that

some classifications are less likely to be legitimate

than others. Racial classifications must be assessed

under the most stringent level of review because

immutable characteristics, which bear no relation

to individual merit or need, are irrelevant to almost

every governmental decision.

448 U.S. at 496, 100 S.Ct. at 2783-84 (Powell, J. concurring).

Subsequent to the Bakke and Fullilove decisions, this cir

cuit considered constitutional attacks on state and local gov

ernment mandated affirmative action plans. In assessing the

constitutional validity of the affirmative action plans at issue

in the post-Bakke and Fullilove cases, this circuit redefined

the term “strict scrutiny” as it applied in affirmative action

cases:

[T]he first stage in our approach to affirmative action

programs entails an analysis of the need for such

remedial measures — i.e., with the presence of a

governmental interest in their implementation. It is

uncontested that the government has a significant

interest in ameliorating the disabling effects of iden

tified discrimination.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, cl al. 9

* * *

Once the governmental interest in some remedial

action is thus established, we must proceed to deter

mine whether the remedial measures employed arc

reasonable.

Bratton v. City o f Detroit, 704 F.2d 878, 886-87 (6th Cir.

1983) (footnote omitted), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 1040, 104

S.Ct. 703, 79 L.Ed.2d 168 (1984). See also Detroit Police Offi

cers' Ass'n v. Young, 608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979) (determin

ing that no “direct showing of past intentional

discrimination” by the governmental unit imposing the affir

mative action plan was necessary and that the plan need only

be a “reasonable” means of serving the governmental interest

of eradicating the effects of past discrimination), cert, denied,

452 U.S. 938, 101 S.Ct. 3079, 69 L.Ed.2d 951 (1981); Ohio

Contractors Ass’n v. Keip, 713F.2d 167 (6th Cir. 1983) (where

compelling interest of state in ameliorating the past effects

of its prior discrimination was clear, the affirmative action

plan adopted need only be “reasonably calculated” to serve

that interest). In these decisions, this court essentially relaxed

the strict scrutiny standard enunciated by the Supreme Court

in Bakke and Fullilove. Thus, this circuit essentially required

that affirmative action plans be a “reasonable” means of fur

thering a “significant” governmental interest rather than a

“narrowly tailored” or “necessary” means of furthering a

“compelling” governmental interest.5

5WhiIc the distinction between the terms “significant” and

“compelling” may be negligible, see Wygant v. Jackson Bd. o f Educ..

476 U.S. 267, 106 S.Ct. 1842, 1853, 90 L.Ed.2d 260 (1986) (O’Connor,

J., concurring)(discussing distinction between terms “compelling” and

“important”), as discussed below, it is clear that the district court in

the case at bar considered the terms as having different meanings when

it expressly refused to require defendants to demonstrate a

“compelling” interest, but instead required them to demonstrate a

“significant interest.” 571 F.Supp. at 176-77.

10 Michigan Road Builders v. Millikan, el al. No. 86-1239

In Wygant v. Jackson Bd. ofEduc., 746 F.2d 1 1 52 (6th Cir.

1984), this circuit again applied its relaxed standard of review

to uphold an affirmative action layoff plan embodied in a col

lective bargaining agreement between a public board of edu

cation and a teachers’ union. In reversing the decision, the

Supreme Court rejected the relaxed level of judicial scrutiny'

imposed by this circuit in Wygant:

This Court has “consistently repudiated ‘[distinc

tions between citizens solely because of their ances

try’ as being ‘odious to a free people whose institu

tions are founded upon the doctrine of equality.’ ”

. . . . “Racial and ethnic distinctions of any sort arc

inherently suspect and thus call for the most exact

ing judicial examination.”

The Court has recognized that the level of scrutiny

does not change merely because the challenged clas

sification operates against a group that historically

has not been subject to governmental discrimina

tion. In this case, [the collective bargaining agree

ment] operates against whites and in favor of certain

minorities, and therefore constitutes a classification

based on race. “Any preference based on racial or

ethnic criteria must necessarily receive' a most

searching examination to make sure that it docs not

conflict with constitutional guarantees.” There are

two prongs to this examination. First, any racial

classification “must be justified by a compelling gov

ernmental interest.” Second, the means chosen by

the State to effectuate its purpose must be “narrowly

: tailored to the achievement of that goal.” We must

decide whether the layoff provision is supported by

a compelling state purpose and whether the means

chosen to accomplish that purpose arc narrowly tai

lored.

Wygant v. Jackson Bd. ofEduc., 476 U.S. 267, 106 S.Ct. 1 842,

1846-47, 90 L.Ed.2d 260 (1986) (plurality opinion) (citations

omitted). Subsequent to rejecting the “compelling” nature of

the governmental interests advanced by the board of educa

tion in support of the constitutional validity of the layoff

plan, which interests had been found to be “sufficiently

important” by this circuit, 106 S.Ct. at 1847-49, the Court

continued:

The Court of Appeals examined the means chosen

to accomplish the Board’s race-conscious purposes

under a test of “reasonableness.” That standard has

no support in the decisions of this Court. As demon

strated . . . above, our decisions always have

employed a more stringent standard — however

articulated — to test the validity of the means cho

sen by a state to accomplish its race-conscious

purposes.6 Under strict scrutiny the means chosen

to accomplish the State’s asserted purpose must be

specifically and narrowly framed to accomplish that

purpose. “Racial classifications are simply too perni

cious to permit any but the most exact connection

between justification and classification.”

The term “narrowly tailored,” so frequently

used in our cases, has acquired a secondary mean

ing. More specifically, . . . the term may be used

to require consideration whether lawful alterna

tive and less restrictive means could have been

used. Or . . . the classification at issue must “fit”

with greater precision than any alternative

means. “[Courts] should give particularly intense

scrutiny to whether a nonracial approach or a

more narrowly tailored racial classification could

promote the substantial interest about as well and

at tolerable administrative expense.”

106 S.Ct. at 1849-50 (citations and footnote omitted). The

Supreme Court left no doubt that the standard of judicial

review previously employed by this circuit in racial and eth

nic affirmative action cases was inappropriate.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 11

In the case at bar, the district court, having issued its opin

ion nearly three years before the Supreme Court reversed this

circuit in Wygant, erroneously decided the constitutional

validity of Public Act 428 under this circuit’s relaxed level

of scrutiny:

“A different analysis must be made when the

claimants are not members of a class historically

subjected to discrimination.”

* * *

Having determined that the law of this Circuit

requires that the State must demonstrate a signifi

cant interest in ameliorating the past effects of pres

ent discrimination rather than the “compelling

interest" standard . . ., this Court must examine the

record to assess the nature of the interest of the State

in enacting [Public Act] 428.

* * *

Having determined that the State has established

its interest in ameliorating the present effects of past

discrimination, this Court must now determine

whether [Public Act] 428 is a reasonable means of

achieving that end.

571 F.Supp. at 176-77, 187 (quoting Bratton, 608 F.2d at

697). The district court’s analysis represented an erroneous

application of strict scrutiny as that term has been defined

and employed by the Supreme Court. In Wygant, the

Supreme Court expressly disapproved of the reasoning

employed by the district court in this case. Although the dis

trict court had properly analyzed the constitutional validity

of Public Act 428 under the law of this circuit as enunciated

in Bratton, Detroit Police Officers' Ass'n, and Ohio Contrac

tors Ass'n when it issued its opinion in this case on August

12, 1983, “an appellate court must apply the law in effect

12 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, ct al. No. 86-1239

at the time it renders its decision.” Thorpe v. Housing Auth.

o f City o f Durham, 393 U.S. 268, 281, 89 S.Ct. 518, 526, 21

L.Ed.2d 474 (1969) (footnote omitted). See also Gulf Offshore

Co. v. Mobil Oil Corp., 453 U.S. 473, 486 n. 16, 101 S.Ct.

2870, 2879 n. 16, 69 L.Ed.2d 784 (1981). Accordingly, in

light of the Supreme Court’s mandate in Wygant, this court

must abrogate the legal conclusions of the district court in

the case at bar.

As indicated by the Supreme Court precedent already dis

cussed, a more appropriate constit utional review of racial or

ethnic classifications adopted by governmental bodies should

be subjected to a two stage evaluation. First, a court must

determine whether a “compelling” state interest supports the

use of the racial or ethnic classification. If the court concludes

that a compelling interest exists, it must then determine

whether the challenged state action employing a racial or eth

nic classification is “ narrowly tailored” or “necessary” to fur

ther that interest.

A state “unquestionably has a compelling interest in reme

dying past and present discrimination by a state actor.”

United States v. Paradise, 107 S.Ct. 1053, 1065, 94 L.Ed.2d

203 (1987) (citations omitted) (plurality opinion). Before a

state may permissibly employ a racial or ethnic classification,

however, it must make a finding based upon material factual

evidence, that it has in the past discriminated against those

classes it now favors. If the state had not engaged in discrimi

nation against racial and ethnic minorities in awarding con

tracts to supply the state with goods and services in the past,

then it cannot assert in praesenli that it has a compelling

interest in preferring MBEs in the award of such contracts.

[The Supreme Court] never has held that societal

discrimination alone is sufficient to justify a racial

classification. Rather, the Court has insisted upon

some showing of prior discrimination by the govern

mental unit involved before allowing limited use of

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 13

14 Michigan Road Builders v. MiUiken, el al. No. 86-1239

racial classifications in order to remedy such dis

crimination.* * * [P]rior discrimination [is] the justi

fication for, and the limitation on, a State’s adoption

of race-based remedies.

★ ★ *

Societal discrimination, without more, is too

amorphous a basis for imposing a racially classified

remedy. * * * No one doubts that there has been

serious racial discrimination in this country. But as

the legal basis for imposing discriminatory legal

remedies that work against innocent people, societal

discrimination is insufficient and over expansive. In

the absence of particularized findings, a court could

uphold remedies that are ageless in their reach into

the past, and timeless in their ability to affect the

future.

* * *

[A State] must act in accordance with a “core pur

pose of the Fourteenth Amendment” which is to “do

away with all governmcntally imposed distinctions

based on race.” * * * In particular, [a state] must

ensure that, before it embarks on an affirmative

action program, it has convincing evidence that

remedial action is warranted. That is, it must have

sufficient evidence to justify the conclusion that

there has been prior discrimination.

Wygant, 106 S.Ct. at 1847-48 (citations omittcd)(some

emphasis added). See also Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307, 98 S.Ct.

at 2757 (“We have never approved a classification that aids

persons perceived as members of relatively victimized groups

at the expense of other innocent individuals in the absence

of judicial, legislative, or administrative findings of constitu

tional or statutory violations. After such findings have been

made, the governmental interest in preferring members of

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. MiUiken, el al. 15

the injured groups at the expense of others is substantial,

since the legal rights of the victims must be vindicated.”) (ci

tations omitted) (emphasis added); J. Edinger & Son, Inc. v.

City of Louisville, 802 F.2d 213, 216 (6th Cir. 1986) (“[T]he

city should be required to present evidence of invidious

discrimination.”); South Fla. Chapter o f Associated Gen. Con

tractors o f Am. v. Metropolitan Dade County, 723 F.2d 846,

851-52 (11th Cir.) (“[Ajdcquate findings [must] have been

made to ensure that the governmental body is remedying the

present effects of past discrimination rather than advancing

one racial or ethnic group’s interests over another___”) (em

phasis in original), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 871, 105 S.Ct. 220,

83 L.Ed.2d 150 (1984); Associated Gen. Contractors o f Cat.,

8 13 F.2d at 930 (“[S]tate and local governments [can] act only

to correct their own past wrongdoing.. . , ”). More recently,

the Fourth Circuit has slated:

[B]efore an asserted governmental interest in a racial

preference can be accepted as “compelling,” there

must be findings of prior discrimination. Findings

of societal discrimination will not suffice; the find

ings must concern “prior discrimination by the gov

ernment unit involved."

* * *

For a locality to show that it enacted a racial prefer

ence as a remedial measure, it must have had a firm

basis for believing that such action was required

based on prior discrimination by the locality itself.

* * *

Wygant... limit[s] racial preferences to what is nec

essary to redress a practice of past wrongdoing.

J.A. Croson Co. v. City o f Richmond, 822 F.2d 1355, 1358,

1360, 1362 (4th Cir. 1987)(citations omitted) (emphasis in

original). Accordingly, in the instant case, this court must

determine whether the Stale of Michigan possessed a compel

ling interest in purging the present effects of alleged past dis

crimination by virtue of its past inequitable treatment ol

MBEs. To accomplish this result, this court must decide

whether the Michigan legislature, based upon the evidentiary

factual record before it, “had a firm basis for believing that

such action was required based on prior discrimination” by

the state itself. J.A. Croson Co., 822 F.2d at 1360.6

An examination of the evidence asserlcdly relied upon by

the defendants in this action as support for their contention

that the Michigan legislature had a firm basis for concluding

that the state had engaged in discrimination in awarding con

tracts for goods and services clearly indicates that Michigan

had not developed material evidence to support a conclusion

that it had a compelling interest in adopting the racial and

ethnic distinctions at issue in the case at bar. The defendants

have relied upon certain conclusory historical resumes of

unrelated legislative enactments and proposed enactments,

executive reports, and a state funded private study conducted

in 1974. This documentation is not reflective of discrimina

tory action by the State of Michigan.7

16 Michigan Road Builders v. Millikcn, el al. No. 86-1239

6Bccause the factual record in this case is complete and this court’s

only function is to determine whether the evidence presented to the

district court satisfied a legal standard, remand is unnecessary. Bose

Carp. v. Consumers Union o f U.S., Inc., 466 U.S. 485, 501, 104 S.Ct.

1949, 1960, 80 L.Ed.2d 502 (1984).

7The defendants in this action have, as a defense, “admitted” that

the State of Michigan had engaged in impermissible discrimination

in the award of state contracts. See generally Appellee's Brief, pp. 29-32.

This “admission” is of little relevance and docs not relieve this court

of its duty to determine whether remedial legislation in the form of

racial and ethnic classifications is, in fact, supported by a compelling

interest in alleviating the present effects of past slate discrimination.

Wyganl. 106 S.Ct. at 1849 n. 5 (“Nor can the [state] unilaterally insu

late itself from this key constitutional question by conceding that it

has discriminated in the past, now that it is in its interest to make

such a concession.”)

The defendants have directed this court’s attention to

“executive memoranda”8 concerning proposed legislation

considered by the Michigan legislature during 1971 and sub

sequent years. The first of these memoranda concern House

Bill (H.B.) 4394 (1971) which would have relaxed bonding

requirements for state construction contracts. The memo

randa conjectured a belief that the state’s stringent bonding

requirements prohibited most small businesses from effec

tively competing for such contracts. The proposed statute

would have assertedly served the dual purpose of fostering

the growth of small businesses in general and benefiting the

state by increasing competition for state construction con

tracts. Fostering the growth of MBEs in particular was not

a concern or purpose expressed in the legislative history of

H.B. 4394.

Senate Bill (S.B.) 885 (1975) would have set aside a per

centage of state goods and services procurement contracts

for small businesses. The asserted purpose of this proposed

legislation was to foster the growth of small businesses in light

of Michigan’s “sluggish economy.” Again, fostering the

growth of MBEs was not a consideration for this proposed

legislation.

S.B. 1461 (1976) and S.B. 10 (1977)9 would have also set

aside an allotment of state contracts for small businesses. The

executive memoranda commenting upon these enactments

suggested that increasing the number of contracts awarded

to small businesses would also increase the number of MBEs,

which were predominantly small businesses, doing business

with the state. In addition, S.B. 1461 included a provision

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 17

The executive memoranda which analyzed pending legislation

were prepared for the Governor by each of the state’s various executive

departments.

9S.B. 1461 and S.B. 10 were essentially identical and were introduced

in successive sessions of the Michigan legislature. Neither proposal was

enacted into law.

18 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, cl al. No. 86-1239

which would have set aside contracts for “socially or econom

ically disadvantaged persons.” In testimony given before the

Michigan Senate State Affairs Committee in support of S.B.

1461, Norton L. Berman, Director of the OfTicc of Economic

Expansion within the Department of Commerce, indicated

that underrepresentation of MBEs in slate contracting

resulted from factors other than discrimination by the State

of Michigan:

Small and minority businesses traditionally have

experienced problems in management, financing,

and market development. These problems often

times result from the inability of small businessmen

to generate sufficient capital to meet their opera

tional needs.

* * *

Through a series of public hearings and question

naires sent to small and minority businesses, busi

ness persons expressed their concerns in several

areas, some of which were: complexity of procure

ment procedures, information distributed of stale

agencies was inadequate, contracts were too large,

there was no requirement on the part of large con

tractors to solicit bids from small and minority sub

contractors, excessive delay in paying vendors,

excessive pre-award costs and bonding requirements

which small and minority businessmen could not

meet.

* * *

[P]ast business patterns have resulted in under rep

resentation of minorities in the business commu

nity. Therefore, I feel the state is remiss if we do

not do what we can to assure that minority business

obtain an equitable share of state purchasing.

I am aware there arc those who view this legisla

tion as preferential treatment and the distortion of

the competitive spirit of purchasing. I agree that this

might be considered so, but unorthodox methods

are needed to create opportunities for a major seg

ment of our society that can contribute more to eco

nomic stability. With regards to competition, what

we have now in many industries is competition

among the small operators and domination by a few

large firms. Large businesses often can sell at a con

siderable lower price because of high volume of

sales, more efficient distribution systems and more

advertising and promotion. Small business cannot

equitably compete because of these disadvantages

of size.

As reflected in Berman’s testimony, the relative lack o

MBEs doing business with the state was coupled with th<

objective reality that most MBEs were small businesses

Small businesses, as a result o f their size, were unable to effec

tively compete for state contracts. Consequently, most MBEs

as a result o f their size, were unable to effectively compeb

for state contracts.

The legislative history of Public Act 428 itself offered m

support for the contention that the State of Michigan inten

tionally discriminated against MBEs. A House Legislativi

Analysis of the bill attributed the scarcity of MBE contract

with the state to the lack of minorities within the busines

community as a result o f societal discrimination:

Statistical descriptions of the extent of participation

in state programs by businesses controlled by

women and minorities are varied and sometimes

contradictory depending on the definitions used and

the samples of state spending examined. These

descriptions, however, all reveal that such busi

nesses receive a disproportionately small share of

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 19

state spending for construction and goods and ser

vices in relation to their proportion of the slate's

population. That minorities and women have been

systematically denied equal opportunity in this

country is sad historical fact now generally accepted

and widely recognized in legislation of the past two

decades. In the interests of justice as well as the

social and economic health of the slate, the legisla

ture should do all that it can to ensure that busi

nesses owned by minorities and women obtain their

fair share of the state’s business.

★ * ★

The federal government and other stale govern

ments are already proceeding in this direction as a

remedy to the underrepresentation of minority and

other segments of business in the business commu

nity. The legal issues are difficult and outcomes of

various litigations impossible to predict. In the

meantime Michigan should continue to be a partici

pant in the enactment of progressive legislation,

which would in any case enhance the growth of these

underrepresented sectors of the business commu

nity, at least until the question of constitutionality

is resolved.

Evidence of societal discrimination, however, is an insuffi

cient basis for the employment of racial and ethnic distinc

tions by state or local governments. Wygant, 106 S.Ct. at

1848; J. Edinger & Son, Inc., 802 F.2d at 216-17.

The evidence consisting of executive action designed to

increase small business and MBE participation was also

insufficient to support a conclusion that the state had discrim

inated against MBEs. In 1975, the Governor issued Executive

Directive 1975-4 creating a task force to study small business

oarticipation in state purchasing. After conducting two public

20 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken. cl al. No. 86-1239

hearings wherein witnesses testified that small and minority

businesses’ size and lack of expertise prohibited them from

effectively competing for state purchasing contracts, the task

force issued its report recommending the adoption of policies

and procedures to aid small and minority businesses in the

state procurement process.

In response to the task force's report, the Governor issued

Executive Directive 1976-4 wherein he established the Small

and Minority Business Procurement Council (Council) to

oversee the declared “policy of tye [sic] executive branch

agencies of the State of Michigan . . . to aid, counsel, assist

and protect the interests of small and minority business con

cerns in order to preserve free competitive enterprise and to

insure that a fair portion of the procurement of state agencies

and agencies of the state be placed with small and minority

business enterprises.” In 1977, the Council issued its first

annual report in which it noted that the objectives establish

ing small and minority business participation in state pur

chasing had been achieved.

In 1975, the Governor also issued Executive Directive

1975-6 wherein he commanded the Michigan Department

of Civil Rights (MDCR) to assist the other state departments

in developing and implementing standards and procedures

to assure nondiscrimination in awarding state contracts. In

1978, the MDCR issued a report in which it expressed con

cern over limited compliance with Executive Directive 1975-

6 because of the lack of adequate staff in some agencies and

the inexperience of personnel in dealing with civil rights mat

ters. The MDCR did not suggest that limited compliance with

Executive Directive 1975-6 was the result of intentional dis

crimination.

The evidence most heavily relied upon by the defendants

in this action was the report of a 1974 state-commissioned

study by Urban Markets Unlimited, Inc. (Urban Markets).

The report, entitled “A Public Procurement Inventory on

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 21

22 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el a/. No. 86-1239

Minority Vendors,” was prefaced with the rather dubious

statement: “Minority-owned business enterprises arc often

described as being synonymous with small business.”10 The

report noted that there were 8,112 minority businesses in

Michigan, but that in a small sampling of purchase contracts,

only four did business with the state.11 The contracts sam

pled, however, represented only approximately $21 million

of state’s annual expenditures of over $437 million. The sam

pling was necessarily small and of little value because, as the

report noted, the state did not maintain data on minority

procurement by state agencies.12

Because the statistical evidence was not probative of dis

crimination, Urban Markets also circulated questionnaires

to and conducted interviews of state officials responsible for

purchasing goods and services for various state agencies and

departments. Responses to Urban Markets’ inquiries dis

closed that most state agencies did not actively seek new

10The report ofTcrs no evidence for this proposition. While it may

well be true that most MBEs arc small businesses, the notion that the

terms are synonymous is not persuasive. There arc, no doubt, a sub

stantial number of non-minority small businesses, which, because of

their size, also experience problems in effectively competing for stale

contracts. This questionable proposition, upon which much of the

report’s analysis is based, seriously undermines the validity of the con

clusions reached by Urban Markets.

u As an indication that most MBEs were small businesses, Urban

Markets reported that only 2,577 of Michigan’s 8,112 MBEs had paid

employees, and all 8,112 businesses employed a total of only 10,958

persons.

12Only 4 of 26 state agencies maintained data on purchases from

MBEs. Indeed, one of the report’s recommendations was that the state

“establish a means of collecting data on the quantity, types, and dollar

amounts of purchases which the State expends with minority vendors.”

The fact that the state admittedly kept no data on MBE participation

in state contracts seriously undermined the defendants’ attempt to rely

on the “statistical evidence" incorporated into the Urban Markets

report as an indication of past state discrimination.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 23

sources of supplies, but instead relied primarily upon

“already established purchasing contracts” when filling new

orders for goods and services. In particular, the study indi

cated that only three state agencies were using minority busi

ness directories to “actively seek-out” minority suppliers, and

that some purchasing officials expressed unfavorable impres

sions of the qualiP' and reliability of performance afforded

by small and minority businesses. Significantly, Urban Mar

kets did not conclude that state purchasing policies were dis

criminatory, but rather “[m]ost agencies indicated that

awards [were] based upon the lowest satisfactory bid.”

Most damaging to the defendants’ contention that the

Michigan legislature was motivated by a compelling interest

to eradicate the effects of past state discrimination when it

enacted Public Act 428 were defendants’ responses to plain

tiffs’ interrogatories in this action. Plaintiffs requested the

defendants to identify the findings of past discrimination

against each of the minority groups favored in Public Act

428, and defendants responded to each interrogatory as fol

lows:

(1) Upon information and belief, the Michigan Leg

islature found that

(a) there had been a history of significant politi

cal, economic, and cultural discrimination based

upon race, ethnic origin, and sex in the United

States, including Michigan; and

(b) among the racial and ethnic minorities who

have been the victims of such discrimination are

Eskimos, Hispanics, Orientals, Indians (Native

Americans), Blacks; and

(c) Females have been the victims of discrimina

tion based upon sex; and

(d) as a result of the discrimination described in

1(a) above, racial and ethnic minorities and females

have been subjected to economic disadvantages; and

24 Michigan Road Builders v. Mi/liken, el at. No. 86-1239

(e) amonglhe consequences of the discrimination

described in 1 (a) and (d) above, has been an inability

to compete on an equal competitive level for access

to contracting opportunities with government,

including but not limited to such opportunities with

the State of Michigan; and

(f) as a result of competitive limitations imposed

on racial and ethnic minorities and females because

of the discrimination aforesaid, other persons not

in those categories enjoy an artificial and unfair

advantage in the competitive process; and

(g) the advantages resulting to persons not subject

to discrimination based upon racial or ethnic con

siderations or those of gender reduce competition

for state contracts and thereby result in greater costs

to the taxpayers for goods and services needed by

the State of Michigan; and

(h) establishment of goals and timetables effect

ing state procurement policies was the most effective

feasible means available to remedy the present

effects of the discriminatory history and conditions

described in 1(a), (d), and (e) above; and

(i) increases in the number of businesses qualified

to compete for state contracts will result in a cost

benefit to the taxpayers.

In addition, the plaintiffs directed the defendants to identify

documents supporting the legislature’s conclusion that the

state had discriminated against minorities and women in the

award of state contracts. In their answer, the defendants,

other than referring to the evidence discussed above, again

relied upon societal discrimination, referring generally to

“the history of the western world for the past 2000 years.”

Furthermore, the state again acknowledged that it did not

maintain records concerning the number of MBEs which bid

on slate contracts and the number which were awarded state

contracts.

After reviewing the record in its entirety as developed

before the district court, this court concludes that the Michi

gan legislature had little, if any, probative evidence before

it that would warrant a finding that the State of Michigan

had discriminated against MBEs in awarding state contracts

for the purchase of goods and services. At best, the evidence

suggested that societal discrimination had afforded the obsta

cle to the development of MBEs in their business relationship

with the State of Michigan. Consequently, relatively few

MBEs exist,13 and those that do are generally small in size

and have difficulty in competing for state contracts as a result

o f their size. The evidence does not prove that the State of

Michigan invidiously discriminated against racial and ethnic

minorities in awarding state contracts. Accordingly, this

court concludes that the state has not supported its conclu

sion that it had a compelling interest in establishing the racial

and ethnic classifications contained in Public Act 428, and

those classifications are, therefore, constitutionally invalid.14

With regard to the preference accorded WBEs by Public

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, cl al. 25

13Bcrman testified in support of S.B. 1461 that minorities comprise

13.73% of the general population of Michigan, but MBEs comprised

only 5.85% of the businesses within the state.

14Thcrc is no proof to support preference for the groups listed in

Public Act 428, i.c., persons who arc “black, hispanic, oriental, cskimo,

or an American Indian.” Mich. Comp. Law § 450.771(c). In the

answers to plaintiffs’ interrogatories, defendants admitted that they

were “unaware” of how many MBEs in each of the above minority

groups bid for and were awarded state contracts. A finding of “prior,

purposeful discrimination against members of each of these [favored]

minority groups” is required before state and local governments are

permitted to remedy alleged discrimination by the enactment of laws

embodying racial and ethnic distinctions. Wygant, 106 S.Ct. at 1852

n. 13. See also J.A. Croson Co., 822 F.2d at 1361; Associated Gen. Con

tractors o f Cal., 813 F.2d at 934.

26 Michigan Road Builders v. Millikan, cl al. No. 86-1239

Act 428, the Supreme Court has employed a less stringent

standard of review or level of scrutiny for gender based classi

fications:

Our decisions also establish that the party seeking

to uphold a statute that classifies individuals on the

basis of their gender must carry the burden of show

ing an “exceedingly persuasive justification” for the

classification. Kirchbcrg v. Feenstra, 450 U.S. 455,

461, 101 S.Cl. 1 195, 1199, 67 L.Ed.2d 428 (1981);

Personnel Administrator o f Mass v. Feenev, 442 U.S.

256, 273, 99 S.Ct. 2282, 2293, 60 L.Ed.2d 870

(1979). The burden is met only by showing at least

that the classification serves “important governmen

tal objectives and that the discriminatory means

employed” are “substantially related to the achieve

ment of those objectives.” Wengler v. Druggists

Mutual Ins. Co., 446 U.S. 142, 150, 100 S.Ct. 1540,

1545, 64 L.Ed.2d 107 (1980).

Mississippi Univ. for Women v. Ilogan 458 U.S. 718, 724,

102 S.Ct. 3331,3336, 73 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1982)(footnotc omit

ted). Although the Supreme Court has never expressly

defined these terms, “substantially related to serve an impor

tant governmental interest” is regarded as a less stringent

judicial standard of review than “narrowly tailored to serve

a compelling governmental interest.” Associated Gen. Con

tractors of Cal., 813 F.2d at 939 (describing level of scrutiny

for gender based classifications as “mid-level review”).

Even under this less stringent standard of review, the WBE

preferences in Public Act 428 cannot withstand constitu

tional attack since evidence of record that the state discrimi

nated against women is nonexistent. Defendants’ reliance

upon general assertions of societal discrimination are insuffi

cient to satisfy their burden absent some indication that the

“members of the gender benefited by the classification actu

ally suffered] a disadvantage related to the classification.”

Mississippi Univ. for Women, 458 U.S. at 728, 102 S.Ct. a

3338. Defendants presented no evidence that WBEs sufferei

a disadvantage in compel' ng for state contracts. Accordingly

Public Act 428’s gender-based classifications are als<

invalid.15

For the foregoing reasons, this court concludes that Publi

Act 428, Mich. Comp. Laws § 450.771 et seq., is unconstitu

tional. Consequently, the judgment of the district court i

REVERSED and the case is REMANDED for entry of judg

ment in favor of the plaintiffs in accordance with this opir

ion.

No. 86-1239 Michigan Raad Builders v. Milliken, cl al. 2'

15Becausc this court concludes that Michigan lacked a “compellinj

interest to support the racial and ethnic distinctions, and r

“important” interest to support the gender based distinction

embodied in Public Act 428, this court does not address the sccor

prong of the constitutional elimination, i.e., whether the means we

“narrowly tailored” and “substantially related” to the achievement i

its goal of eradicating the present effects of prior discrimination.

LIVELY, Chief Judge, dissenting. Because I disagree with

both major premises of the majority opinion, I must respect

fully dissent.

28 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, cl al. No. 86-1239

I.

The majority reads Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986), as if it changed all the previously

accepted standards for judging the validity of affirmative

action programs of governments and governmental units.

That is not a fair appraisal of the purport or effect of Wygant.

In Wygant itself the Court noted that it is necessary in some

cases to take race into account, and emphasized the differ

ence in consequences flowing from a program such as the one

involved in this case and one that requires layoffs, as the plan

in Wygant did. This emphasis was made by contrasting the

minority set-aside program that the Court had approved in

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980), with the plan

under consideration in Wygant, which did require layoffs:

We have recognized, however, that in order to

remedy the effects of prior discrimination, it may

be necessary to take race into account. As part of

this Nation’s dedication to eradicating racial dis

crimination, innocent persons may be called upon

to bear some of the burden of the remedy. “When

effectuating a limited and properly tailored remedy

to cure the effects of prior discrimination, such a

‘sharing of the burden’ by innocent parties is not

impermissible.” Id. [Fullilove, 448 U.S.] at 484, 100

S. Ct. at 2778, quoting Franks v. Bowman Transpor

tation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 96 S. Ct. 1251,47 L.Ed.2d

444 (1976). In Fullilove, the challenged statute

required at least 10 percent of federal public works

funds to be used in contracts with minority-owned

business enterprises. This requirement was found to

be within the remedial powers of Congress in part

because the “actual burden shouldered by nonmi

nority firms is relatively light.” 448 U.S. at 484, 100

S. Ct. at 2778.

Significantly, none of the cases discussed above

involved layoffs. Here, by contrast, the means cho

sen to achieve the Board’s asserted purposes is that

of laying off nonminority teachers with greater

seniority in order to retain minority teachers with

less seniority. We have previously expressed con

cern over the burden that a preferential layoffs

scheme imposes on inn,.cent parties. See Firefighters

v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, 574-576, 578-579, 104 S. Ct.

2576,____ ______ , 81 L.Ed.2d 483 (1984); see also

Weber, n. 9, supra this page, 443 U.S. at 208, 99

S. Ct. at 2730 (“The p;an does not require the dis

charge of white worker:; and their replacement with

new black hirees”). In cases involving valid hiring

goals, the burden to be borne by innocent individu

als is diffused to a considerable extent among society

generally. Though hiring goals may burden some

innocent individuals, they simply do not impose the

same kind of injury that layoffs impose. Denial of

a future employment opportunity is not as intrusive

as loss of an existing job.

106 S. Ct. at 1850-51 (foo.notes omitted).

The Michigan program is similar to the federal MBE pro

gram in Fullilove. At most, nonminority owned businesses

will be required to share the state’s contracts with minority

owned businesses; no white owned business will be removed

from a previously awarded contract. I believe this case is con

trolled by Fullilove and Ohio Contractors Ass’n v. Keip, 713

F.2d 167 (6th Cir. 1983), rather than by Wygant.

The Supreme Court has been unable to agree on the precise

level of scrutiny required when considering race conscious

programs to assist minorities. While there is a consensus that

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 29

race conscious programs demand an elevated level of scru

tiny, the Court has not defined that level. This is clear from

an examination of the plurality opinions from Regents of the

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), to

United States v. Paradise, _ U.S. 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987).

In fact a plurality of the Court in Paradise, a ease subsequent

to Wygant, noted it has “yet to reach consensus on the appro

priate constitutional analysis.” Id. at 1064.

Despite this uncertainty, at least two prerequisites for a

constitutionally acceptable race conscious program arc

clearly established. The program must be in response to a

compelling state goal and it must be narrowly tailored to

achieve that goal. The majority concedes, as it must, that the

State of Michigan has a compelling interest in eliminating

race and gender discrimination from its procedures for

awarding public contracts. I believe the Michigan program

also satisfies the second requirement in that it is narrowly

tailored. Given the subject matter involved—public contract

ing — it is hard to conceive of a difTcrcnt approach that would

achieve the state’s legitimate goals in a less intrusive way.

In my opinion the plan chosen by Michigan to correct a sys

tem that virtually excluded minority contractors in the past

“fits” the situation better than any alternative means. See

Wygant, 106 S. Ct. at 1850 n. 6, where the Court discusses

the meaning of “narrowly tailored,” and quotes Professor

Ely’s definition: “the classification at issue must ‘fit’ with

greater precision than any alternative means.”

II.

I also disagree with the majority’s conclusion that the State

of Michigan did not develop material evidence that estab

lished the existence of past discrimination or the need for

a program to increase minority participation. An examina

tion of the record totally refutes this conclusion. The district

court found that the Michigan legislature considered the fol

lowing evidence before finally adopting P.A. 428 in 1981:

30 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, cl a/. No. 86-1239

No. 86-1239 Michigan Roc;:! Builders v. Milliken, el at. 31

1. An Executive Memorandum concerning House

Bill No. 4394 (1971). The bill was to help small busi

nesses receive government contracts; MBEs consid

ered to fall within the classification of a small busi

ness. Bill and Memorandum indicate early concern

for plight of minorities. 571 F. Supp. 178-79.

2. A study commissioned by the state in 1974 to

explore the state’s procurement policies and its

effects upon minorities (the Urban Markets Unlim

ited Study). Report issued in 1974 examined the

procurement opportunities that were available to

minority businesses, concluding that opportunities

were not great, and that purchasing agents expressed

negative attitudes toward minority vendors. Id. at

179-81.

3. Three Senate bills introduced in 1975-77 (Sen

ate Bills 885 (1975), 1461 (1976), and 10 (1977)).

These bills addressed set-asides for small businesses,

but were also designed to address the problems fac

ing minority businesses. Id. at 181.

4. Testimony of Nonon L. Berman, Director of

Office of Economic Expansion, Michigan Depart

ment of Commerce, concerning Senate Bill 1461

and encouraging legislature to enact set-asides. Id.

at 181-82.

5. The Governor’s Executive Directive 1975-4

(1975), creating a Task Force on Small Business Par

ticipation in State Purchasing. Directive empha

sized minority businesses and the difficulty they

have had getting into the mainstream of business.

Id. at 182.

6. Two public hearings of the Task Force, where

views were expressed concerning the difficulties of

minority businesses. Id. at 183.

32 Michigan Road Builders v. Midi ken, el al. No. 86-1239

7. The Task Force’s Final Report (March 1976),

recommending, inter alia, that goals be established

for the participation of MBEs in state procurement.

Id. at 183.

8. The Governor’s Executive Directive 1976-4'

(1976), stating that it is the executive branch’s policy

to ensure that MBEs get a fair portion of business

with the state and creating the Small and Minority

Business Procurement Council. Id. at 183.

9. The First Annual Report of the Council (1977),

noting that the commitment for MBEs was reached

in the first year. Id. at 183-84.

10. The Governor’s Executive Directive 1975-6

(1975), directing the Michigan Department of Civil

Rights to, inter alia, establish standards to assure

non-discrimination in state contracting. Id. at 184.

11. The May 15, 1978 Report of the Department

of Civil Rights, expressing concern over limited

progress that had been made under Directive

1975-6. Id. at 184.

12. Proposed House Bill 4335, initiated March

15, 1979, which provided for MBE set-asides, and

later, WBE set-asides. Id. at 184-85.

House Bill 4335 was adopted by the legislature two years

after it was introduced, and became P.A. 428, the Act at issue

in this case. The district court concluded that this evidence

was sufficient for “the Legislature to make a finding of past

intentional discrimination.” Id. at 187. This is a finding of

fact that is fully supported by the record and is not clearly

erroneous.

The majority’s conclusion that the evidence in this case

at best suggested “that societal discrimination had afforded

the obstacle to the development of MBEs in their business

No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 33

relationship with the State of Michigan” has no support in

the record. The Supreme Court has determined that societal

discrimination in and of itself is not sufficient justification

for enactment of an affirmative action plan. Wygant, 106 S.

Ct. at 1847. As the Coun noted in Bakke, it has never

“approved a classification that aids persons perceived as

members of relatively victimized groups at the expense of

other innocent individuals in the absence of judicial, legisla

tive, or administrative findings of constitutional or statutory

violations.” 438 U.S. at 307. Societal discrimination is best

exemplified in Wygant. The school board extended preferen

tial protection against layoffs to minority employees in'ordcr

to provide minority students with minority role models. In

holding this was an insufficient justification, the Court noted

there must be some showing of prior discrimination by the

governmental unit and that the plan must have a remedial

purpose.

The legislative record in this case clearly shows that the

plan enacted by the State of Michigan was not designed solely

to aid persons perceived as members of “relatively victimized

groups” or to create “role models” for minorities. As noted,

the Michigan Legislature began in 1971 to review the prob

lem of limited participation of minority and woman owned

businesses in the state’s procurement of goods and services.

The plan that was adopted approximately nine years later

was the culmination of numerous studies, hearings and pro

posals to rectify the situation. Any acceptable understanding

of the concept of federalism; requires us to accord the same

degree of deference to the findings of a state legislature follow

ing years of study and investigation that we give to findings

of Congress. The majority’s rejection of the legislative show

ing of prior discrimination is improper, not only because it

fails to give the deference that a federal court should give

to a state legislature’s findings, but because the level of find

ings which the majority would exact from the legislature has

not heretofore been required.

The Supreme Court noted in FuUilovc that “Congress, of

course, may legislate without compiling the kind o f ‘record’

appropriate with respect to judicial or administrative

proceedings. 448 U.S. at 478. The Court determined that

Congress had abundant evidence from which it could .con

clude that minority businesses have been denied effective

participation in public contracting opportunities by procure

ment practices that perpetuated the effects of prior

discrimination.” Id. at 477-78, There is sufficient evidence

in the legislative record or Michigan Public Act 428 to sup

port a determination that the state’s procurement practices

did perpetuate the effects of prior discrimination, resulting

in an extremely small percentage of contracts being awarded

to minority and woman owned businesses.

As we stated in Ohio Contractors Ass'n v. Keip, 713 F.2d

at 173:

The state has chosen to remedy the effects of its

own past discriminatory practices by means of a pro

gram which imposes relatively light burdens on the

majority group which was in position to benefit from

those practices.

(Emphasis in original). Michigan did the same thing for the

same reasons.

Finally, in my opinion the majority places entirely too

much emphasis on semantics. The district court’s use of

‘ significant” as opposed to “compelling” in describing the

state’s interest is immaterial, given that the state clearly did

have a compelling interest in eliminating discriminatory

practices from its contracting and procurement procedures.

Although the district court referred to a “reasonableness” test

in reviewing the means chosen by Michigan to deal with the

state s interest, in actually testing the MBE program the dis

trict judge expressly analyzed all of the factors that the plural

ity of the Supreme Court analyzed in applying the “narrowly

tailored” standard in Fullilove. 571 F. Supp. at 188.

34 Michigan Road Builders v. Mi/liken, cl al. No. 86-1239 No. 86-1239 Michigan Road Builders v. Milliken, el al. 3

1 would affirm the judgment of the district court.