Brewer v. The School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief and Appendix for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brewer v. The School Board of the City of Norfolk, Virginia Brief and Appendix for Appellants, 1970. 2dc43357-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96c6e063-c3d7-4593-a61a-df8d7d707c41/brewer-v-the-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-virginia-brief-and-appendix-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

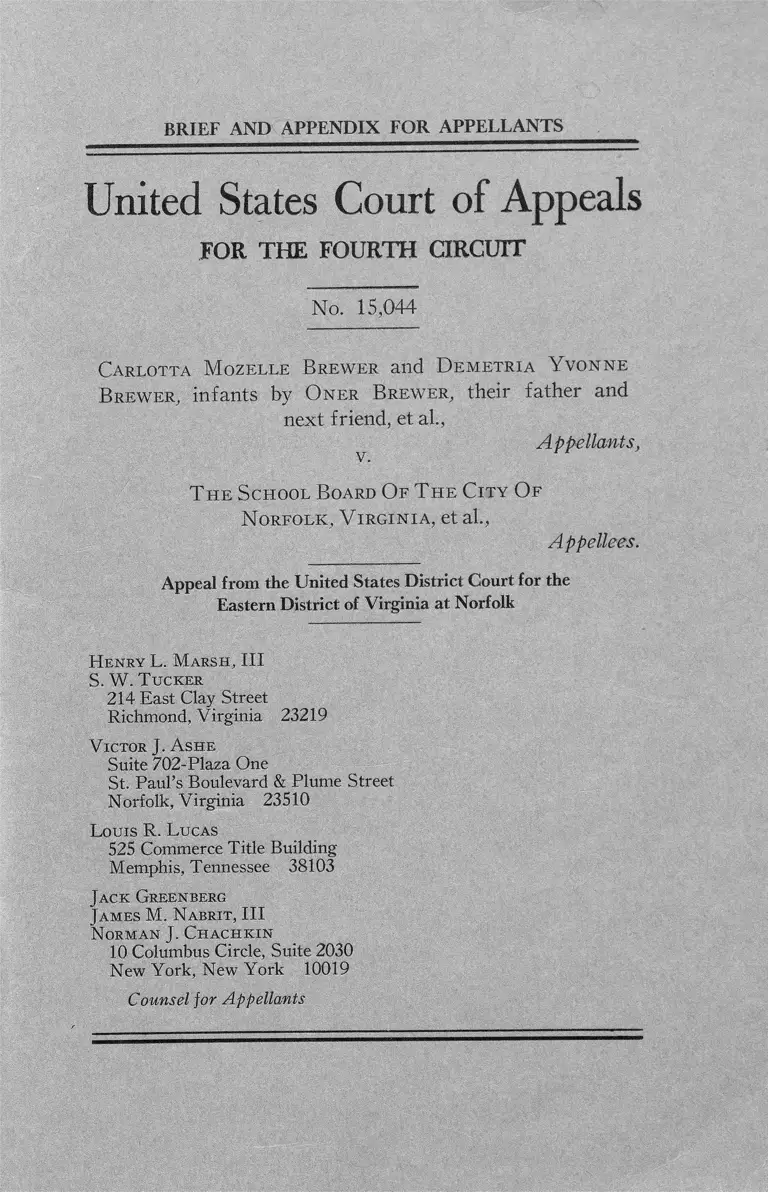

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR APPELLANTS

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 15,044

Carlotta M ozelle Brewer and Demetria Y vonne

Brewer, infants by O ner Brewer, their father and

next friend, et al.,

v. Appellants,

T he School Board O f T he City O f

Norfolk, V irginia, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia at Norfolk

H enry L. M arsh , III

S. W. T ucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A she

Suite 702-Plaza One

St. Paul’s Boulevard & Plume Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23510

Louis R. L ucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

Page

Issues Presented For R eview ....... .............. ..................................- 1

Statement O f T he Case .............—— ........................................ 2

Statement Of Facts ...... -.................. -...................... -.............. ........ 6

High Schools ..................................................................................... 7

Junior High Schools ........................ -.......... -................................... 9

Elementary Schools .........-.....- ........-.............. -................. ............ 10

All Schools ........................................................................-............... 12

Transportation .............................................. 13

A rgument .................................... ....................................-.............. 15

I. Norfolk’s Plan And Its Deliberate Failure To Vindicate

Immediate And Urgent Constitutional Rights Constitute A

Flagrant Violation Of This Court’s Orders In this Case..... IS

A. The Board’s Actions Demonstrate An Overt Hostility

To The Mandate Of This C ourt.......................................... 15

B. The Board Permitted Impermissible Considerations To

Affect Its Decisions.... .............................................. -........... 18

II. This Court Should Now Order Implementation Of The

Alternative Plan In The Record Which All Parties Agree

Is The Best Plan To Totally Desegregate The School

System..... ................... - ................... -............................................ 19

Conclusion ...... .......................-............................................................. 20

TA B LE OF CASES

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, No. 14,544 (C.A. 4,

June 22, 1970 ......... ................... -...........-.................... -................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I ) , 347 U.S. 483 .............. 20

Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County, 413

F.2d 53 (4th Cir. 1969) ................................................................. 18

TABLE OF CONTENTS

18

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg, ..... F.2d ..... (4th Cir., No.

14,517 and No. 14,518, May 26, 1970) .......................... 18, 19, 20

Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County, 413 F.2d

53 (4th Cir. 1969)

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) ..........

18

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 15,044

Carlotta M ozelle Brewer and D emetria Y vonne

Brewer, infants by O ner Brewer, their father and

next friend, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

T he School Board O f T he City O f

Norfolk, V irginia, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia at Norfolk

BRIEF FO R APPELLANTS

ISSUES PRESENTED FO R R E V IE W

I

Whether Norfolk’s plan, which assigns 62 per cent of

its black students and 52 per cent of its white students to

racially segregated schools, satisfies the requirements of

the Constitution and the mandate of this Court that the

Norfolk School Board must operate a unitary school system.

2

II

Whether this Court should order implementation o f the

alternative plan in the record which all parties agree is the

best plan to totally desegregate the school system.

ST A T E M E N T O F T H E CASE

Following the June 22, 1970 decision by this Court in

this case, the District Court entered an order on June 23

requiring the defendants to submit a plan for unitary schools

on or before July 27, 1970. In language identical to that in

this Court’s opinion, the order further provided:

“ (2 ) The plan may be based on the suggestions made

by the Government’s expert witness, Dr. Michael J.

Stolee, or on any other method that may be expected

to provide a unitary school system.

“ (3 ) The plan shall immediately desegregate all senior

high schools.

“ (4 ) The defendants shall explore reasonable methods

of desegregation of all elementary and junior high

schools, including rezoning, pairing, grouping, school

consolidation, and transportation. If it appears that

black residential areas are so large that all schools

cannot be integrated, the plan must assure that no pupil

is excluded because o f his race from a desegregated

school.” [Appendix (hereinafter referred to as A .)

p. 1 ); Record (hereinafter referred as to R .) pp.

982-83]

The order of the District Court further stated:

“ In attempting to interpret the opinion of the appellate

court, even though the Court of Appeals does not ex

pressly so decide, this Court is of the view that the ap

pellate court has effectively approved racial balancing

for all schools with the possible exception o f the ele

mentary schools in Berkley-Campostella area. To ac

3

complish this end result extensive cross-bussing will

be required. Although the appellate court says nothing

as to the impossibility o f obtaining school buses for the

school year beginning September 1970, it is obvious

that such is impossible. The only solution, if it can be

referred to in that manner, is for the School Board

to contract with the Virginia Transit Company for

as many buses as possible, and then stagger the opening

and closing of all schools to meet the transportation

problem, irrespective of inconveniences to pupils and

faculty” (A . p. 3; R. p. 985).

Over the strenuous objection of the plaintiffs, and with

the acquiescence of the defendants, the Court permitted

certain white citizens to intervene as parties-defendant (Tr.

Vol. X X X V I, pp. 13-28). These defendants indicated that

they would assert:

(1 ) That the present operation of the Norfolk city

schools does not violate the “ constitutional rights of

the plaintiffs or of any other person,”

and

(2 ) “ That the relief prayed for by the plaintiffs in

their recent appeal o f this action to the Court o f Ap

peals, 4th Circuit, that all public schools in the city of

Norfolk, Virginia, be racially balanced, will violate the

constitutional rights of these intervenors and all others

similarly situated.” (R. p. 1026)

On July 27, 1970, plaintiffs moved the Court for an

order joining the Council of the City of Norfolk and the

individual members thereof as parties-defendant. Plaintiffs

urged that such joinder was necessary to insure that what

ever orders the District Court might enter would be binding

on all parties having responsibility for the operation of

Norfolk public schools (R. p. 996). This motion was denied

4

by the District Court on July 29, 1970 (Tr. Vol. X X X V I,

p. 39).

On July 27, 1970, the last day on which the board was

permitted by the Court to file its plan, the board met and

approved a plan which was on that day fded with the Court

(R. p. 999).

The plan filed by the board contained schedules showing

the estimated results anticipated in the racial mix o f the

student bodies of each school. (See Appendix pages 4

through 17, and School Board Exhibits 1-1 and 1-3

[1970]; R. pp. 1000-18.) For a comparison of the ele

mentary enrollment under the board’s 1970 plan with that

o f the “ Long Range Plan” condemned in the June 22

opinion, see Government’s Exhibit 3 [1970] (A . pp. 20-21).

The plan also contained a “ Revision of Stolee Plan A ”

and a “ Revision of Stolee Plan C” and the estimated results

under each plan. The Stolee A revision consists of seven

groupings or clusters of three schools each and indicates

the board’s best judgment of the “ grouping required within

the constraint of having contiguous zones.” (School Board

Ex. 1-4 [1970] A. p. 6; R. p. 1017.)

The Stolee C revision indicates the board’s best judgment

of the “ groupings necessary for the desegregation of all of

the elementary schools north of the Eastern Branch of the

Elizabeth River.” This revision would cluster or pair all

but thirteen of the fifty-four elementary schools and would

result in a minimum racial mix of 20% in all but five of

the elementary schools. (See A. pp. 16-17 and School Board

Exhibit 1-5 [1970]; R. pp. 1013-14.)

The school board made it clear that it did not favor any

of the plans which would provide any significantly addi

tional racial mix. It pointed out that the revised Stolee plans

were submitted “ [i]n order that the Court may compare

5

the disadvantages of any such plan(s)” (A . p. 6; R. p.

1002).

On August 4, 1970, the plaintiffs filed exceptions to the

plan of the school board (A . pp. 18-19; R. pp. 1037-39).

Plaintiffs objected to the assignment provisions for each

level of education, the failure of the board to provide (free)

transportation for all pupils, to the special facilities and

program provision of the plan, and to failure of the plan

to protect black administrators and teachers.

The United States filed exceptions on August 3, chal

lenging the elementary assignment plan, the rising senior

provision, the absence of free transportation for indigent

students and for students exercising their rights under the

majority to minority transfer provision, the failure of the

board to protect black administrators and teachers, and the

absence of reporting provisions (R. pp. 1033 and 1034).

On August 5, 1970, the United States filed a submission

purporting to contain two alternative plans for the opera

tion of the elementary schools (R. pp. 1040-42).

After two days o f hearings held on August 11 and

August 12, 1970, the Court filed a Memorandum-Order on

August 14. The Court overruled plaintiffs’ exceptions and

approved the board’s plan, with certain modifications at the

elementary level. (A . pp. 22-44; R. pp. 1060-87).

Plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal on August 18, 1970

(R. p. 1093).

On August 17, plaintiffs moved for an injunction pend

ing appeal to restrain the defendants from refusing to im

plement for the 1970-71 school year, the Stolee plan or

some other plan which would effectively desegregate each

school operated by the school board (R. p. 1090). The mo

tion was denied by the District Court (R. p. 1092).

On August 27, 1970, the court entered an order formally

approving the board’s plan with certain modifications (R.

6

pp. 1100-1103). The order required the board to file on or

before September 15, 1970, “ a schedule setting forth for

the system as a whole and for schools at each level of the

system” certain statistical data including the numbers and

percentages of white and black students in each school.

Portions o f this report, which was filed on September 22,

1970, are reproduced herein (A . pp. 49-51).

Defendant-intervenors filed their Notice of Appeal on

August 20, 1970. (R. p. 1097). That appeal, which is be

ing considered together with this appeal, is designated No.

15,045. The School Board of the City of Norfolk filed its

Notice of Appeal on August 27, 1970. (R. p. 1106). That

appeal, designated No. 15,046, is also being considered at

this time.

ST A T E M E N T OF FACTS

The pertinent facts concerning the Norfolk school system

during the 1969-70 school year were as cited in this Court’s

June 22, 1970 opinion, v iz :

“ Approximately 56,600 pupils, of whom 32,600 are

white and 24,000 are black, attend the Norfolk schools.

During the 1969-70 school year the board operated five

senior high schools. One of these was all black, and

more than half of Norfolk’s black high school pupils

attended it. The other four had enrollments ranging

from 9% to 53% black.

“ O f the eleven junior high schools, five enrolled about

77% of the district’s black junior high pupils. Four of

these schools were virtually all black and one was 91 %

black. At the other extreme, three junior high schools

were 92% to 97% white. The remaining three schools

had black enrollments of 12%, 16%, and 54%.

“ The district had 55 elementary schools. Eighty-six

per cent of the black pupils attended twenty-two schools

7

which were more than 92% black. In contrast, 81%

of the white pupils attended twenty-five that were more

than 92% white. The remaining- eight schools had

student bodies from 10% to 75% black.

“ During the 1969-70 school year, most of the schools

could be racially identified by the composition of their

faculties. At only two o f the seventy-three schools

did the assignment of faculty reflect the racial compo

sition of the district’s teachers, which is approximately

34% black and 66% white. Throughout the district

only 16% of the teachers were assigned across racial

lines.

“ The evidence clearly depicts a dual system of schools

based on race.” Brewer v. School Board o f City o f

Norfolk, No. 14,544 (C.A. 4, June 22, 1970).

High Schools

At the time the board decided on its plan, black high

school students constituted from 36% to 38% of the high

school population. The board recognized that if a minority

of white students was assigned to Booker-T, there was a

danger that many white students would not show up and

that resegregation would occur. Dr. McLaulin indicated

that “ the best opportunities for stabilization” would be

offered with 65% white and 35% black at Booker-T (Tr.

Vol. X X X V II, page 141).

The high school plan approved below contained a rising-

senior option. The board believed that most of the seniors

would exercise their option and remain at the schools they

attended in previous years (Tr. Vol. X X X V II, page 153).

Clearly, it expected 75% to 80% white enrollment at Lake

Taylor, Granby and Norview and 65% to 70% black at

Booker-T (Tr. Vol X X X V II, p. 153). This expectation

was realized in the September 16 enrollment data:

8

Total % White °fo Black

Granby High 2218 75 25

Lake Taylor High 2513 77 23

Norview High 2388 72 28

Washington High 1854 17 83

Maury High 2133 45 55

T otal Senior H igh 11,106 59 41

The high school assignment was made b j adjusting- the

boundary lines which were in effect last year. In some cases,

non-contiguous geographical zones were utilized (See

School Board Ex. 1-1 [1970]). Dr. McLaulin admitted

that by using non-contiguous zones and by adjusting the

zone lines, the five high schools could have been racially

balanced as under the Long Range Plan which the board

had proposed to achieve by 1972 (Tr. Vol. X X X V II, pp.

134-d36). However, the board abandoned its plan to

balance the high schools and rejected all options for further

desegregation at the high school level because of the ap

parent opposition of black and white children and their

parents (Tr. Vol. X X X V II, pp. 134, 241, 291).

Dr. McLaulin, the principal architect of the school

board’s plan, indicated that in view of the fact that over

forty per cent of Norfolk’s pupils are black, he did not con

sider a school containing a 10% racial minority of students

a desegregated school. He indicated that his goal in prepar

ing the plan was to achieve “ a critical mass of students in

a school of a given race, whether they be black students or

white students” and that as a general guide, in his judg

ment, a school with a racial minority of 25 per cent or less

would not have such critical mass (Tr. Vol. X X X V II, pp.

146 and 151 [1970]).

9

Junior High Schools

The Enrollment Report shows that 55% of the junior

high school pupils are white and 45% are black.

The feeder plan adopted by the board for the junior high

assignment resulted in the following enrollment in the city’s

ten junior high schools:

Total % W h ite % Black

Azalea Gardens Jr. 1441 9 9 1

Campostella Jr. 1134 1 99

Ruffner Jr. 1042 7 93

Northside Jr. 1377 90 10

Jacox Jr. 791 15 85

Norview Jr. 1204 65 35

Rosemont Jr. 891 62 38

Willard Jr. 1161 57 43

Lake Taylor Jr. 1224 56 44

Blair Jr. High 1454 60 40

T o t a l J r . H ig h 11,719 55 45

The five schools first listed above, which enroll 49% of

the junior high pupils, are clearly racially identifiable. None

of the five possesses the “ critical mass” as defined by the

board’s expert.

The following information, which was taken from the

enrollment report (A . p. 49), shows the racial character of

the junior high schools as they are currently operating under

the court approved plan:

1 0

100% 100% Minority Minority less All

Black White 10% or less than 25% Schools

C l a ss if ic a t io n of Ju n io r H ig h S ch ool E n ro llm e n ts

Number of Schools 0

Students in Each Classification:

Total Students

Number 0

Percentage 0

Black Students

Number 0

Percentage 0

White Students

Number

Percentage . .

0 4 5 10

0 4994 5785 11,719

0 42% 49%

2244 2917 5296

- 42% 55%

0 2750 2868 6423

0 43% 45%

As is indicated above, 55% of the black junior high school

students, 45% of the white junior high school students and

49% of all junior high students attend schools that are

racially identifiable.

Elementary Schools

The board described its elementary plan as “ an area-

attendance plan under which children residing with an at

tendance area will attend the school serving that area (A .

p. 6, R. p. 1001). With the exception of several minor

changes in the elementary lines which were effected prior

to this Court’s June 22 decision, the elementary plan is

virtually the same plan which was condemned by this Court

in its previous decision. The plan anticipated that 16 schools

would remain all black, 9 would be all white, 11 would en

roll 10% or less black students. Only 5 of the 54 schools

would enroll racial minorities of at least 25%. The overall

percentage at the elementary level is 56% white and 44%

black.

11

When compared with the Long Range elementary plan,

27 of the 54 schools in the proposed plan had the identical

percentage of black and white students and 42 of these

schools had percentages within 5 percentage points of that

indicated in the rejected plan. A comparison of the results

expected under the two plans is contained on Government’s

Ex. 3 (A . pp. 21-22).

The modifications ordered by the District Court amended

the school board plan by grouping 15 elementary schools

in five separate clusters of 3 schools each (A . p. 37; R. p.

1079). These five clusters are among the seven indicated by

the school board in the revision of Stolee A which was filed

with the July 27, 1970 plan (A . p. 14; R. p. 1011). The

racial percentages resulting from the modified plan are

shown on the board’s enrollment report (A . pp. 49-51).

Under the modified plan, 21 of the 551 elementary schools

enrolled pupils of only one race, 32 o f the 55 schools enrolled

racial minorities of 10% or less, and 36 o f the 55 schools

enrolled racial minorities of less than 25% (A . pp. 49-51).

The following information, which was taken from the

enrollment report (A . pp. 49-51), shows the racial character

of the elementary schools as they are currently operating

under the court approved plan:

1 Only 54 schools are shown on Gov. Ex. 3 [1970] (A. pp. 20-21).

Norview Elementary is divided into Norview Elementary and Nor-

view Annex to add an additional school in the Enrollment Report

(A . p. 50).

12

100% 100% Minority Minority less All

Black White 10% or less than 25% Schools

C l a ssif ic a t io n of E l e m e n t a r y S ch ool E n r o llm e n ts

Number of Schools 14 7

Students in Each

Classification:

Total Students

Number

Percentage

7595

24%

3865

12%

Black Students

Number

Percentage

7595

52%

White Students

Number

Percentage

3865

22%

32 36 55

17,736 20,793 31,8222

56% 65%

9604 10,164 14,639

66% 69%.

8132 10,629 17,183

47% 62%

Sixty-nine per cent of the black elementary pupils, 62%

of the white elementary pupils and 65% of all elementary

pupils attend racially segregated schools under the plan

approved by the District Court.

All Schools

The enrollment report submitted by the school board

reveals the extent to which desegregation has occurred in

the City of Norfolk under the modified plan. The informa

tion printed below shows that 62% of all black students,

52% of all white students, and 57% of all students are still

attending racially segregated schools.

2 The Enrollment Report shows a total elementary enrollment of

31,632. Addition of the individual school enrollments, however, gives

a total enrollment of 31,822.

13

C l a ssif ic a t io n of A ll S ch ool E n ro llm e n ts

100%

Black

100%

White

Minority

10% or less

Minority less

than 25%

All

Schools

Number of Schools 14 7 36 43 70

Students in Each

Classification:

Total Students

Number

Percentage

7595

14%

3865

7%

22,730

42%

30,945

57%

54,647

Black Students

Number

Percentage

7595

31%

11,848

48%

15,198

62%

24,436

White Students

Number

Percentage

3865

13%

10,882

36%

15,747

52%

30,211

T ranspor t ation

The number of students estimated to be transported for

1970-71 was determined by counting last year’s (1969-70)

trip requirements and adding to that number an estimate of

the trips needed for 1970. The number of 1970 trips was

determined by counting the total number of pupils to be

transferred away from each school as indicated by the par

ticular plan under consideration and dividing by 60. For

example, the transportation requirements for the revision

of Stolee A were ascertained by counting by school the

total number of pupils assigned to a different school. The

number for each school was then divided by 60 to determine

the number of trips required. To this number was added

the number of trips needed by schools not changed by the

plan. See Plaintiff’s Ex. 3 [1970] and Tr. Vol. X X X V III

pp. 379, 384.)

The estimate of the elementary requirements under the

school board’s plan was based on the full 37 trips made in

1969 plus 23 new trips which were determined by counting

the total number of pupils transferred to a different school

14

and dividing by 60. The same procedure was followed in

making the estimates at all three levels of education (Tr.

Vol. X X X IX pp. 403-4).

The estimated requirements for the Revised Stolee C

were determined in the same manner. For each school, the

number of pupils transferred to a different school was

divided by 60 to determine the number of trips. The total

number o f trips was then added to the trips for schools

not grouped. Each trip was counted as one bus in deter

mining the number of buses required (Tr. Vol. X X X V III

pp. 355, 360, 381-85 and Plaintiff’s Ex. 4 [1970]). In

determining the number of trips, where there were less

than sixty pupils they would be counted as one trip and

assigned one bus (Tr. Vol. X X X V III p. 357).

In all areas where the bus company had no prior exper

ience in transporting pupils, they assumed that 100% of the

students transferred to a different school would ride on a

special bus (Tr. Vol. X X X V III pp. 344-45, 359), regard

less o f the existence of regular line service (Tr. Vol.

X X X V III pp. 345-46), regardless of the proximity of the

pupils to the school (Tr. Vol. X X X V III pp. 360-61, Tr.

Vol. X X X IX pp. 436-38), even in cases where the pupils

lived next door to the school (Tr. Vol. X X X IX pp. 436-38).

The company did not take into consideration the pupils who

are transported by their parents or in car pools, pupils who

drive or ride with others, or pupils who walk to school (Tr.

Vol. X X X V III pp. 359-361).

The company assumed that each trip would require 45

minutes regardless of the distance of the trip and even

though many trips would only require 6 to 8 minutes (Tr.

Vol. X X X IX pp. 427-30, 432-34 and 439-43). Although

in previous years many trips have been combined on one

run, no such effort had been made in arriving at the 1970

estimates (Tr. Vol. X X X IX pp. 403-404). Moreover, trips

for each school are listed independently, although two

15

schools are located in the same area (Tr. Vol. X X X V III

pp. 393-96).

An analysis of the 1969-70 special bus schedule route

indicates that the average trip is in the range of 20-25

minutes rather than 45 minutes (Sch. Bd. Ex. 3 p. 5 and PX

2). However, the company allocated 45 minutes for each

trip. The bus company official conceded that he could

shorten many trips by picking up pupils at a central place

rather than winding through each neighborhood to pick up

children. He stated that he had considered but had not imple

mented a policy of one stop in a central area (Tr. Vol.

X X X IX p. 435).

The company official indicated that only 75 or 77 buses

were available for special school routes during the peak

morning hours. However, in view of his admission that

buses from the morning peak period became available as

early as 8:30 A.M., it is obvious that a different staggering

of openings would make more vehicles available for special

routes.

Mr. Little admitted that no allowance had been made

for special runs which were discontinued or unnecessary

after the 1969-70 school year (Tr. Vol. X X X IX pp. 412-

18).

A R G U M E N T

I .

Norfolk’s Plan And Its Deliberate Failure T o Vindicate Immediate

And Urgent Constitutional Rights Constitute A Flagrant Vio

lation O f This Court’s Orders In This Case.

A

The Board’s Actions Demonstrate An Overt Hostility

To The Mandate O f This Court

Notwithstanding 14 years of litigation seeking to end

racially segregated education in the city’s public schools,

16

more than one-half of the Norfolk’s public school children

are assigned by the school board to racially segregated

schools. Notwithstanding the mandate of this Court follow

ing its June 22, 1970 opinion, the Norfolk School Board

filed and the Court below approved a plan which assigned

most of Norfolk’s children to racially segregated schools.

The order entered on this Court’s mandate directed the

board to submit a plan for unitary schools for the 1970-71

school year. The board responded by adopting a plan which

at the elementary level was patterned on an area-based or

neighborhood-school concept and which was nearly identical

to the plan rejected by this Court in the previous appeal,

and at the junior and senior high level the plan assigned

approximately one-half of the children to racially segre

gated schools.

In the preamble of its plan the board stated:

“ In accomplishing all of the mixing of races of pupils

that can be reasonably attained, the School Board has

attempted to preserve an educationally sound school

system, but in certain instances, the requirements of

the Courts for racial mix are contrary to the best judg

ment of the School Board.” (A . p. 4; R. p. 1000).

In spite of the consensus by all parties to this litigation

that extensive transportation of students will be necessary

to effect meaningful integration the plan states:

“ The School Board has never in the past and does not

now consider the operation by it o f a bus system for

the transportation of pupils between home and school

to be either necessary or educationally desirable. It has

not construed the court decisions and orders in this case

to require the inauguration of such a system.

“ The implementation of any Stolee-type plan is limited

by the capacity of the public bus transportation system

17

as it may be rearranged to provide maximum effi

ciency.” (A . pp. 6, 7; R. p. 1000).

As expressed by the Superintendent, the attitude of the

board has been:

“A. * * * This was not a matter of choosing what

we wanted. We had what we wanted in the other plan.

Q. You are referring to the long range plan?

A. That’s right. W e had what we wanted in the

other plan.” (Tr. Vol. X X X V II, p. 287)

This defiant attitude by the defendants, -which has been

demonstrated over the years, has been apparent since the

June 22 decision of this Court.

Although the order on the mandate was entered on June

23, the board did not decide on its plan until July 27, the

last day for its filing with the Court. The plan it finally

submitted practically disregarded the requirements of this

Court. In fact, no other plan considered by the board pro

vided for less desegregation than the one it selected (Tr.

Vol. X X X V II, pp. 166-7).

The board acknowledged that additional transportation

was required to substantially increase the desegregation

provided by its plan. Yet, it failed to give the transporta

tion requirements of its plans to the transit officials until

July 30 or later (Tr, Vol. X X X V III, p. 342). Moreover,

the information finally given the transit company was

grossly inflated and patently unrealistic.

The plaintiffs offered to show that an ample supply of

used buses was available to the Virginia Transit Com

pany, but that the board had made no inquiry of the com

pany concerning additional transportation facilities (Offer

of Proof of Plaintiffs, Tr. Vol. X X X V II, p. 231-3).

18

The board’s action in welcoming the Interveners into

the case to fight for freedom of choice and neighborhood

schools while opposing the joinder of the City Council

which could appropriate funds needed for implementing de

segregation orders is further evidence of the board’s atti

tude.

B

The Board Permitted Impermissible Considerations To

To Affect Its Decisions

It is clear that the board’s decision to limit desegregation

of the high schools and of the other levels of education has

been based in part on the consideration of the opposition of

white and black parents and children (Tr. X X X V II, pp.

134, 241, 291). The fear of resegregation has been cited

as a reason for limiting the amount of desegregation in

many areas of the board’s activity.

The public’s unwillingness to accept certain amounts of

bussing to accomplish desegregated schools has been cited

by the defendants and the Court on several occasions.

This Circuit has laid to rest all notions that community

opposition can defeat the equal protection rights of black

children to receive an integrated education. Walker v.

County School Board o f Brunswick County, 413 F.2d 53

(4th Cir. 1969) (per curiam ); Hawthorne v. County

School Board of Lunenburg County, 413 F.2d 53 (4th Cir.

1969); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg,___F .2d___ (4th

Cir., No. 14,517 and 14,518, May 26, 1970). See also

Monroe v. Board o f Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

Notwithstanding this Court’s opinion in this case and

Swann, supra, the board continues to rely on the area

based or neighborhood school concept to justify its elemen

tary plan. As this Court stated in Swann :

1 9

“ The district court properly disapproved the school

board’s elementary school proposal because it left about

one-half of both the black and white elementary pupils

in schools that were nearly completely segregated.”

II.

This Court Should Now Order Implementation O f The Alternative

Plan In The Record Which All Parties Agree Is The Best Plan

T o Totally Desegregate The School System.

In the June 22 opinion in this case, this Court issued the

following instructions:

“ The district court shall direct the school board to sub

mit a plan for unitary schools on or before July 27,

1970. The plan may be based on suggestions made by

the government’s expert witness, Dr. Michael J. Stolee,

or on any other method that may be expected to pro

vide a unitary school system.”

Dr. McLaulin, who prepared the board’s plan, frankly

admitted that, given Dr. Stolee’s purposes ( desegregating

all of the schools without regard to an area based limita

tion), the Stolee plan was as good as could be drawn (28

Tr. 97-98).

In its current plan, the board states:

“ As shown by the previous evidence in this case, any

plan for this City effecting substantially more racial

mix at the elementary level than herein provided for

must inevitably be developed along the lines proposed

by Dr. Stolee.” (A . p. 6; R. p. 1002)

Although the District Court and all parties below recog

nize that the Stolee C series is the only plan to totally de

segregate the Norfolk school system, it is now apparent

that if such plan is to be ordered, it must be ordered by this

Court.

2 0

“Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Ed., 396 U.S. 19

(1969), and Carter v. West Feliciana School Bd., 396

U.S. 290 (1970), emphasize that school boards must

forthwith convert from dual to unitary systems. In

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Ed., 418 F.2d 1040

(4th Cir. 1969), and Whittenberg v. School Dist. of

Greenville County, ---- F.2d ...... (4th Cir. 1970), we

reiterated that immediate reform is imperative.”

(Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., supra)

C O N C L U SIO N

The picture presented by this appeal is only slightly

different from that in the previous appeal. The school sys

tem is slightly less segregated than it was last May. The

white citizens opposing the Brown decision have now for

mally entered the case and are fighting at the side of— and

with the cooperation of— the school board to defeat the

rights of the black plaintiffs. The United States of America

in the lower court took a position nearly identical with that

of the school board and has declined to join in the appeal to

this Court. Moreover, the District Judge still proclaims that

he will not order substantial relief for the black plaintiff

class.

Since 1956, when this litigation was commenced, only

the black plaintiffs have remained constant. The record re

veals some signs that the frustration of 15 years of segrega

tion and defeat is beginning to take its toll. An increasing

number of blacks are now openly demanding separation.

Because of the inordinate delays in effecting relief for the

plaintiff class, the rule of law is now facing a growing chal

lenge which promises to increase with the passage of time.

For the reasons stated above, the judgment of the Dis

trict Court should be reversed and the defendants should

21

be required to implement the plan prepared by Dr. Michael

J. Stolee (referred to as the Stolee C series) or some other

plan which will create a unitary system at the earliest prac

tical date.

Respectfully submitted,

H enry L. Marsh, III

O f Counsel for Appellants

H enry L. M arsh , III

S- W. T ucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

V ictor J. A she

Suite 702-Plaza One

St. Paul’s Boulevard & Plume Street

Norfolk, Virginia 23S10

Louis R. L ucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

A P P E N D I X

TABLE OF C O N TEN TS

App. Page

Order of United States District Court—filed June 23, 1970 ......... 1

Plan of School Board, 1970-71— filed July 27, 1970 .................... 4

Exhibit 1-A— Senior High Enrollment .................................... 9

Exhibit 2—Junior High School Feeder Plan............... ............ 10

Exhibit 3-A— Elementary School Enrollment...... .................... 12

Exhibit 4-A— Revision of Stolee Plan “A ” ............................. - 14

Exhibit S-A— Revision of Stolee Plan “ C” ----------------- -------- 16

Plaintiff’s Exceptions to Plan— filed August 4, 1970 .................... 18

Comparison of Long Range Plan With 1970 Plan [Government

Exhibit No. 3]— filed August 12, 1970 ...................... ............. 20

Memorandum of United States District Court-—filed August

14, 1970 ................................ ............................................. -....... 22

Order of United States District Court—filed August 27, 1970 ....... 45

School Enrollment— September 16, 1970 ......................... -.......... - 49

ORDER

Filed June 23, 1970

The Court having received a copy of the opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit,

filed June 22, 1970, and in anticipation that the mandate

shall be received forthwith, and

In obedience to the opinion of said United States Court

o f Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, the Court, acting sua

sponte, doth

Order that—

(1) The defendants shall submit a plan for unitary

schools on or before July 27, 1970.

(2 ) The plan may be based on the suggestions made

by the Government’s expert witness, Dr. Michael J. Stolee,

or on any other method that may be expected to provide a

unitary school system.

(3 ) The plan shall immediately desegregate all senior

high schools.

(4 ) The defendants shall explore reasonable methods of

desegregation of all elementary and junior high schools,

including rezoning, pairing, grouping, school consolidation,

and transportation. If it appears that black residential areas

are so large that all schools cannot be integrated, the plan

must assure that no pupil is excluded because of his race

from a desegregated school.

(5 ) In any school remaining predominantly black, the

plan must make available to such black pupils, on an inte

grated basis, such special classes, functions and programs

as will afford such black children an introduction to inte

gration. Any plan must provide for the assignment of black

pupils attending predominantly black schools to integrated

schools for a substantial portion of their school careers.

App.2

(6 ) The plan shall freely allow majority to minority

transfers and shall provide transportation by bus or com

mon carrier to any pupil desiring to exercise the majority

to minority transfer right. No percentage limitation shall be

imposed upon such transfer right other than the fact that

it be a majority to minority transfer.

(7 ) The plan must provide for the assignment o f facul

ties, subject to exceptions for specialized faculty positions,

so that in each school the racial ratio shall be approximately

the same as the ratio throughout the system, same to be

effective with the school year beginning September 1970.

The foregoing is substantially verbatim with the require

ments of the United States Court o f Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit. The entry o f this order does not in any manner

indicate agreement with the findings or procedure.

The plaintiff and plaintiff-intervenors shall file, on or

before August 3, 1970, any exceptions to said plan.

Assuming that exceptions will be filed, a hearing on

same will be conducted on August 11, 1970, beginning at

9:30 a.m. No requests for a continuance will be considered

as the time schedule fixed by the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit is such that it is impos

sible to grant any continuance.

Any plan approved by this Court must be effective in

September 1970, and it should be noted that the district

court has no authority or power to stay the execution of

any order approving such plan. Any stay order must be

granted by the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit or the United States Supreme Court.

Once again, the appellate court has declined the invita

tion to define an “ integrated” school, a “ desegregated”

school, or a “unitary” school system. An appropriate guide

line would assuredly assist the school boards and lower

courts. While it appears from the opinion that all schools

App. 3

need not be “ integrated” if the size of the black residential

areas are so large that it is impossible to do so, no suggestion

is made as to where these areas may be located, although

this factual information was available in the record. In

attempting to interpret the opinion of the appellate court,

even though the Court of Appeals does not expressly so

decide, this Court is of the view that the appellate court

has effectively approved racial balancing for all schools

with the possible exception of the elementary schools in

Berkley-Campostella area. To accomplish this end result

extensive cross-bussing will be required. Although the ap

pellate court says nothing as to the impossibility o f obtain

ing school buses for the school year beginning September

1970, it is obvious that such is impossible. The only solution,

if it can be referred to in that manner, is for the School

Board to contract with the Virginia Transit Company for

as many buses as possible, and then stagger the opening and

closing of all schools to meet the transportation problem,

irrespective of inconveniences to pupils and faculty.

The Court does not construe the opinion as requiring free

transportation to anyone, although the opinion does require

that transportation by bus or common carrier shall be pro

vided for pupils exercising the majority to minority transfer

provision. Whether, as to these pupils, free transportation

must be provided is an open question. As to Booker T.

Washington High School, “desegregation” must be effected

by September 1970. To accomplish this purpose massive

bussing of white children to the school, to replace black

children who must be moved to another school, is required.

The Clerk will forward certified copies of this order to

all counsel o f record.

/ s / W alter E. H offman

United States District Judge

At Norfolk, Virginia

June 23,1970

App. 4

T H E SC H O O L B O AR D O F T H E C IT Y O F N O R F O L K PLAN

F O R U N IT A R Y SC H O O LS FO R T H E 1970-71 Y E A R

Filed July 27, 1970

I.

P urpose.

The Plan is designed to effectuate a constitutionally ap

propriate unitary school system in compliance with the

requirements of the Decision of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, entered on June 22,

1970, and the Order of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Virginia entered pursuant thereto

on June 23, 1970. In accomplishing all of the mixing of

races of pupils that can be reasonably attained, the School

Board has attempted to preserve an educationally sound

school system, but in certain instances, the requirements of

the Courts for racial mix are contrary to the best judgment

of the School Board.

II.

Faculty.

Teachers will be assgined in the best interests o f the

school system to the end that faculties o f the schools will

reflect the ratio of available white and Negro teachers in

the system for the Plan year.

Instructional and supervisory teaching personnel, not

assigned to a specific school, will approximately reflect the

ratio of white and Negro teachers in the system.

The system has approximately two-thirds white and one-

third Negro teachers. Ratios and numbers are subject to

reasonable variances and to administrative necessities under

the limitations of teacher qualifications and program re

quirements, but no adjustments will be made to avoid racial

balance of faculties.

App.5

III.

School Organization.

A. Senior High Schools.

The City is divided into five (5 ) senior high school at

tendance areas, with each area served by a single school

and designated by the name of such school. Subject to

provision for the rising-senior option hereinafter set forth,

children residing within an attendance area will attend the

school serving that area. The boundaries of the senior high

school attendance areas for the Plan year are shown on the

map identified as “ Map— Senior High Schools,” attached

hereto as Exh ibit 1 and the estimated results thereof in

terms of racial mix of pupils are as shown on Exh ibit 1-A.

Work toward constructing a new high school on Tide

water Drive at the head of Mason Creek was suspended

upon disapproval of the Long Range Plan in connection

with which that site was determined. The construction o f a

new high school at a site near the present Washington High

School is proposed, subject to effective implementation of

this overall Plan.

B. Junior High Schools.

Children are assigned to junior high schools through a

feeder system under which the graduates of each elementary

school are assigned to a particular junior high school. The

elementary schools selected to feed each of the junior high

schools and the results in terms of racial mix o f each school

are set forth on Exh ibit 2.

C. Elementary Schools.

The Board has explored reasonable methods of desegre

gation, including rezoning, pairing, grouping, school con-

App. 6

solidation, and transportation. The Plan proposed by the

Board is an area-attendance plan, under which children

residing within an attendance area will attend the school

serving that area. The boundary lines o f each attendance

area are shown on the map identified as “ Map— Elementary

Schools,” attached hereto as E x h ib it 3, and the estimated

results thereof in terms of racial mix o f pupils in each

school are as shown on the schedule attached hereto as

E xh ib it 3-A.

The School Board recognizes that its judgment as to the

reasonableness of the Plan will be reviewed by the Courts.

As shown by the previous evidence in this case, any plan

for this City effecting substantially more racial mix at the

elementary level than herein provided for must inevitably

be developed along the lines proposed by Dr. Stolee. In

order that the Court may compare the disadvantages of any

such plan, the grouping required within the constraint of

having contiguous zones is shown on the map identified as

“ Revision of Stolee Plan A ,” attached hereto as Exh ibit

4, and the estimated results thereof in terms of racial mix

are as shown on Exh ib it 4-A. The disadvantages en

countered with groupings necessary for the desegregation

o f all o f the elementary schools north of the Eastern Branch

of the Elizabeth River are shown on a map identified as

“ Revision of Stolee Plan C,” attached hereto as Exh ib it 5,

and the estimated results thereof in terms o f racial mix are

as shown on E xh ib it 5-A.

D. Transportation o f Pupils.

The School Board has never in the past and does not

now consider the operation by it of a bus system for the

transportation of pupils between home and school to be

either necessary or educationally desirable. It has not con-

App. 7

strued the court decisions and orders in this case to require

the inauguration o f such a system.

The implementation of any Stolee-type plan is limited by

the capacity of the public bus transportation system as it

may be rearranged to provide maximum efficiency.

IV.

T ransfer P rovisions .

Any pupil will be permitted to transfer from the school

to which he is assigned where his race is in the majority to

a school which has a minority of his race and has available

space in grade. Rules of uniform application designed to

encourage desegregation will be established by the School

Board. The administrative procedure for such transfers

shall be readily available to each child. At such time as the

transportation requirements can be determined, the best

available transportation will be arranged for transferring

students at the expense of the student.

V.

S p e c ia l F a c il it ie s and P rograms.

There are to be a number of special schools and programs

which are not specifically provided for above.

Norfolk Vocational Technical Center, situate on the

Military Highway, established in September, 1968, pro

vides for daily instruction on a half-day basis to children

from all of the City’s high schools. The racial composition

of the Center approximately reflects the racial composition

of the high school student body. The Center is operating

successfully and its programs will be maintained.

; Several programs are conducted under provisions of Title

I o f the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. By

their terms, the programs are designed for the benefit of the

App. 8

disadvantaged children. They are operated by the School

Board on a desegregated basis, but involve primarily Negro

children because of the high correlation between Negro

children and the disadvantaged.

The School Administration will develop compensatory

educational methods for use in any school which remains

predominantly Negro. Compensatory programs will include

such elements as reduced teacher-pupil ratio, revised ad

ministrative organization for instruction, individualized in

struction, supplementary pupil services, and augmented cul

tural and recreational activities.

All pupils will be assigned to integrated schools for a

substantial portion of their school careers, most for at

least half o f it. Special classes, functions, and programs

such as those set forth above will be available to pupils in

predominantly Negro schools on an integrated basis.

VI.

A d m in i stration .

The School Administration will make such administrative

transfers of classes of children or individual children as are

desirable for the orderly operation of the public schools of

the City, such transfers being necessary from time to time

for various reasons which include but are not limited to

the following: to prevent overcrowding of a school building,

to comfortably fill a school building, or to adjust for dam

age to or destruction of a school building, provided that such

transfers will not be made to perpetuate segregation.

The School Administration will also make such adminis

trative transfers of classes of children or individual children

as are desirable to provide for the needs of children for

special subjects, to provide for the needs of mentally or

physically disabled children, or to relieve hardships on chil-

App. 9

dren or their parents or guardians, provided that such trans

fers will not be made to perpetuate segregation.

In the event a child’s residence is moved from one at

tendance area to another during a school year, the child may,

at the option of his parent or guardian, complete such

school year at the school which he is attending at the time

his residence is moved.

In the event the residence of a child who has begun the

eleventh grade is moved from one attendance area to

another, the child may, at the option of his parent or

guardian, remain through graduation in the school in which

he began the eleventh grade.

A rising senior who is assigned under this Plan to a

different high school from that attended in the preceding

year may, at the option of the parent or guardian, remain

through graduation at the school to which he was assigned

for the preceding year.

E X H IB IT 1-A

Sen io r H igh S chools

Estimated Enrollment and

Racial Distribution

School

Estimated,

E nrollm ent*

P ercentage

W h ite

P ercen tage

N egro

Granby 2250 75% 25%

Lake Taylor 2300 65% 35%

Maury 1900 50% 50%

Norview 2300 70% 30%

Washington 2300 48% 52%

* Includes approximately 700 ninth grade pupils.

N o te : Estimated enrollment and percentages of white and Negro

pupils does not take into account the option of seniors to re

main in the same school where they completed the 11th grade.

App. 10

E X H IB IT 2

Ju n io r H ig h S chool F eeder P lan

Estimated Enrollment and

Racial Distribution

1970-71

Junior H igh

S chools

F eed er E lem entary

Schools

Estim ated

Enrollm ent

P ercen tage

W h ite

P ercen tage

N eg ro

Azalea Gardens Bay View

Tarrallton

Little Creek Elementary 1300 100% 0%

Blair

Larchmont

Stuart

Taylor

Sewells Point

Camp Allen

Meadowbrook

Madison

Monroe ( West of

Colonial Avenue) 1250 64% 36%

Campostella

Gatewood

St. Helena

Lincoln

Tucker

Diggs Park

Campostella Elementary 1000 0% 100%

Jacox

Coleman Place

West

Roberts Park

Bowling Park 1025 35% 65%

Lake Taylor

Carey

Fairlawn

Easton

Poplar Halls

Lee

Chesterfield

Liberty Park 1200 60% 40%

App. 11

Junior H igh

S chools

F eed er E lem entary

S chools

Estimated

E nrollm ent

P ercentage

W h ite

P ercentage

N egro

Northside

Willoughby

Ocean View

Calcott

Oceanair

Granby Elementary

Suburban Park 1200 88% 12%

Norview

Norview Elementary

Lindenwood

Sherwood Forest

Lansdale 1250 65% 35%

Rosemont (Upon

the completion

of additions)

Oakwood

Crossroads

Larrymore 850 70% 30%

Ruffner

Goode

Ingleside

Young Park

Titus

Tidewater Park

Pineridge 1360 25% 75%

Willard

Lakewood

Lafayette

Ballentine

Marshall

Monroe (East of

Colonial Avenue) 1225 60% 40%

* Pretty Lake Primary, East Ocean View Primary and Little Creek Primary will

feed into Little Creek Elementary School.

App. 12

E X H IB IT 3-A

E l e m e n ta r y S chools

Estimated Enrollment and

Racial Distribution

1970-71

Elementary

Schools Grades

Estimated

Enrollment

Percentage

White

Percentage

Negro

Ballentine 1-6 285 98% 2%

Bay View 1-6 815 100% 0%

Bowling Park 1-6 775 0% 100%

Calcott 1-7 840 100% 0%

Camp Allen 1-6 900 80% 20%

Campostella 1-6 200 25% 75%

Carey 1-6 400 0% 100%

Chesterfield 1-7 600 13% 87%

Coleman Place 1-7 950 100% 0%

Crossroads 1-6 975 90% 10%

Diggs Park 1-6 615 0% 100%

Easton 1-7 475 94% 6%

East Ocean View 1-4 190 0% 100%

Fairlawn 1-6 460 98% 2%

Gatewood 1-6 400 0% 100%

Goode 1-6 475 0% 100%

Granby 1-7 700 84% 16%

Ingleside 1-6 475 96% 4%

Lafayette 1-6 300 50% 50%

Lakewood >■, 1-6 780 83% 17%

Lansdale 1-6 700 95% 5% .

Larchmpnt 1-6 625 72% 28%

Larrymore 1-6 1075 . 77% 23%

Lee kn: 1-6 600 17% 83%

App. 13

Elementary

Schools (Grades

Estimated

Enrollment

Percentage

White

Percentage

Negro

Liberty Park 1-7 625 0% 100%

Lincoln 1-6 320 0% 100%

Lindenwood 1-6 650 23% 77%

Little Creek Elementary 4-6 730 100% 0%

Little Creek Primary 1-4 615 100% 0%

Madison 1-7 800 0% 100%

Marshall 1-7 600 0% 100%

Meadowbrook 1-6 540 80% 20%

Monroe 1-6 950 17% 83%

Norview 1-6 725 72% 28%

Oakwood 1-6 490 30% 70%

Oceanair 1-6 795 100% 0%

Ocean View 1-7 850 94% 6%

Pineridge 1-6 370 93% 7%

Poplar Halls 1-6 550 94% 6%

Pretty Lake 1-4 105 100% 0%

Roberts Park 1-6 545 0% 100%

St. Helena 1-6 400 0% 100%

Sewells Point Elementary

and Annex 1-6 720 80% 20%

Sherwood Forest 1-6 725 100% 0%

Stuart 1-6 850 17% 83%

Suburban Park 1-6 500 85% 15%

Tarrallton 1-5 725 98% 2%

T aylor 1-6 275 82% 18%

Tidewater Park 1-6 500 0% 100%)

Titus 1-6 610 0% 100%

Tucker 1-6 450 0% 100%

West 1-6 500 0% 100%

Willoughby 1-6 650 90% 10%

Young Park 1-6 650 0% 100%

App. 14

E X H IB IT 4-A

R evision of Stolee

P la n A

Elementary Estimated Percentage

Group Schools Grades Enrollment White

1 Calcott 5-6 650

Crossroads 1-4 900

Oakwood 1-4 550

2100 75%

2 Granby 1-4 820

Suburban Park 1-4 620

Stuart 5-6 610

2050 57%

3 Larchmont 1-4 675

Madison 5-6 525

Taylor 1-4 435

1635 50%

4 Lakewood 1-4 825

Lafayette 1-4 365

Lindenwood 5-6 500

1690 60%

5 Coleman Place 1-4 825

Ballentine 1-4 250

Roberts Park 5-6 575

1640 70%

6 Lansdale 5-7 700

Pineridge 1-4 425

Bowling Park 1-4 925

2050 55%

7 Liberty Park 5-6 570

Ingleside 1-4 430

Poplar Halls 1-4 550

1550 65%

Percentage

Negro

25%

43%

50%

40%

30%

45%

35%

App. 15

Elementary

Group Schools Grad

S chools N o t G rouped

Bay View 1-6

Camp Allen 1-6

Campostella 1-6

Carey 1-6

Chesterfield 1 -7

Diggs Park 1-6

Easton 1-7

East Ocean View 1-4

Fairlawn 1-6

Gatewood 1 -6

Goode 1-6

Larry more 1-6

Lee 1-6

Lincoln 1-6

Little Creek

Elementary 4-6

Little Creek

Primary 1-4

Marshall 1-7

Meadowbrook 1-6

Monroe 1-6

Norview 1-6

Oceanair 1-6

Ocean View 1-7

Pretty Lake 1-4

St. Helena 1-6

Sewells Point

Elementary and

Annex 1-6

Sherwood Forest 1-4

T arrallton 1 -5

Tidewater Park 1-6

Titus 1-6

T ucker 1-6

West 1-6

Willoughby 1-6

Young Park 1-6

Estimated Percentage Percentage

Enrollment White Negro

815 100% 0%

900 80% 20%

200 25% 75%

400 0% 100%

600 13% 87%

615 0% 100%

475 94% 6%

190 0% 100%

460 98% 2%

400 0% 100%

475 0% 100%

1075 77% 23%

500 0% 100%

320 0% 100%

730 100% 0%

615 100% 0%

600 0% 100%

540 80% 20%

950 17% 83%

725 72% 28%

795 100% 0%

850 94% 6%

105 100% 0%

400 0% 100%

720 80% 20%

725 100% 0%

725 98% 2%

500 0% 100%

610 0% 100%

450 0% 100%

500 0% 100%

650 90% 10%

650 0% 100%

App. 16

E X H IB IT 5-A

R e v i s i o n o f S t o l e e

P l a n C

Elementary Estimated Percentage

Group Schools Grades Enrollment White

A Willoughby 5-6 555

Ocean View 1-4 835

Young Park 1-4 600

1990 70%

B Oceanair 1-4 800

Titus 5-6 375

1175 55%

C Bayview 1-4 820

Goode 5-6 450

1270 65%

D Pretty Lake 1-4 140

East Ocean View 1-4 100

Carey 5-6 240

480 50%

E Tarrallton 1-4 930

Lee 5-6 420

1350 65%

F Little Creek

Elementary &

Primary 1-4 1450

Monroe 5-6 945

2395 50%

G Granby 1-4 570

Suburban Park 5-6 540

Marshall 1-4 450

1550 55%

H Sherwood Forest 1-4 825

West 5-6 350

1175 70%

I Fairlawn 1-4 510

Easton 1-4 475

Tidewater Park 5-6 490

1475 60%

Percentage

Negro

30%

45%

35%

50%

35%

50%

45%

30%

40%

App. 17

Elementary Estimated Percentage Percentage

Group Schools Grades Enrollment White Negro

J Calcott 5-6 650

Crossroads 1-4 900

Oakwood 1-4 550

2100 75% 25% .

K Larchmont 1-4 675

Madison 5-6 525

Taylor 1-4 435

1635 50% 50%

L Lakewood 1-4 825

Lafayette 1-4 365

Lindenwood 5-6 500

1690 60% 40%

M' Coleman Place 1-4 825

Ballentine 1-4 250

Roberts Park 5-6 575

1640 70% 30%

N Lansdale 5-7 700

Pineridge 1-4 425

Bowling Park 1-4 925

2050 55% 45%

O Liberty Park 5-6 570

Ingleside 1-4 430

Poplar Halls 1-4 550

1550 65% 35%

Schools Not Grouped

Larrymore 1-6 1075 77% 23%

*Norview 1-6 725 72% 28%

Stuart 1-7 750 50% 50%

Meadowbrook 1-6 540 80% 20%

Camp Allen 1-6 900 80% 20%

*Sewells Point 1-6 720 80% 20%

Chesterfield 1-7 600 13% 87% :

Campostella 1-6 200 25% 75%

T ucker 1-6 450 0% 100%

Diggs Park 1-6 615 0% 100%

Gatewood 1-6 400 0% 100%

St. Helena 1-6 400 0% 100%

Lincoln 1-6 320 0% 100%

* Includes A nnex

E XC E PT IO N S T O T H E PLAN

Filed August 4, 1970

1. The assignment of black and white students on a

50%-50% basis to Maury and on a 52%-48% basis to

Washington fails to erase the racial identifiability of those

schools when their racial composition is compared with

that of other high schools; and such failure carries the

potential of future increases in the percentage o f black

students at Maury and Washington Schools.

2. The rising senior provision of the plan will result

in a substantial maladjustment in the number of black and

white students attending each school as nearly all of the

seniors will elect to remain in the schools which they, re

spectively, attended in 1969-70 and thus to contribute to the

maintenance of the racial identifiability which such school

then had.

3. At the junior high and elementary school levels the

plan proposes obviously white schools and obviously black

schools contrary to the admonition of the Supreme Court

in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County.

4. The plan fails to provide for the transportation of

pupils to the schools to which they are assigned. Having

established and nurtured the dual system, the board may

not transfer to the victims o f that system the financial

burdens incident to its disestablishment.

5. The special facilities and program section of the plan

proposes a substitution of shadow for substance. Brown

dealt with the right of black children to racially non-dis-

criminatory school assignments. This suit was brought to

obtain for black children racially non-discriminatory school

assignments. The rejection o f this suit’s object and the

App. 18

App. 19

substitution of special classes function and programs is a

gross denial o f due process of law.

6. The eleventh grade option provision of the plan is

totally without justification and will delay the elimination

o f the segregated character of the high schools.

7. The plan should provide that the assignment of prin

cipals, assistant principals and other administrative per

sonnel will result in at least as many black administrators

in each o f the above mentioned categories as are presently

employed in the school system.

8. The plan should provide that the board, in its re

cruitment and hiring practices, will not reduce the per

centage of black teachers employed by the Norfolk school

system below the level presently employed by the system.

W herefore , plaintiffs pray that the plan o f the school

board be rejected and that the Court will order the imple

mentation of the plan presented to the Court by Government

Expert, Dr. Michael J. Stolee and referred to as the “ C”

series.

/s / H e n r y L. M arsh , III

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

App. 20

G O V E R N M E N T E X H IB IT N O . 3

Filed August 12,1970

P r o j e c t e d E l e m e n t a r y S c h o o l E n r o l l m e n t A n d

P e r c e n t a g e N e g r o U n d e r T h e S c h o o l B o a r d ' s L o n g

R a n g e P l a n F i l e d 6/21 /69 A n d T h e P l a n F i l e d

7/27/70

Total Enrollment Percentage Negro

School

7/27170

Plant

Ballentine 285

Bay View 815

Bowling Park 775

Calcott 840

Camp Allen 900

Campostella 200

Carey 400

Chesterfield 600

Coleman Place 950

Crossroads 975

Diggs Park 615

East Ocean View 190

Easton 475

Fairlawn 460

Gatewood 400

Goode 475

Granby 700

Ingleside 475

Lafayette 300 .

Lakewood 780

Lansdale 700

Larchmont 625

Larrymore 1,075

Lee 600

Liberty Park 625

Lincoln 320

Long Range

Plan2

7/27/70

Plan1

Long Range

Plan2

675s 2 25s

850 0 0

850 100 100

850 0 0

735 20 25

225 75 75

500 100 100

725 87 85

875 0 0

970 10 35

600 100 100

150 0 0

475 6 10

540 2 0

500 100 100

425 100 100

800 16 15

420 4 10

3 50 3

750 17 15

700 5 10

675 28 25

1,000 23 20

575 83 100

625 100 100

450 100 100

App. 21

School

Total Enrollment Percentage Negro

7127170

Plant-

Long Range

Plan2

7/27/70

Plant

Long Range

Plan2

Lindenwood 650 550 77 100

Little Creek Elementary 730 675 0 0

Little Creek Primary 615 575 0 0

Madison 800 750 100 100

Marshall 600 675 100 100

Meadowbrook 540 575 20 20

Monroe 950 1,000 83 100

Norview 725 700 28 30

Oakwood 490 70

Oceanair 795 750 0 0

Ocean View 850 875 6 10

Pineridge 370 425 7 10

Popular Halls 550 525 6 10

Pretty Lake 105 150 0 0

Roberts Park 545 525 100 100

St. Helena 400 325 100 100

Sewells Point 720 600 20 25

Sherwood Forest 725 725 0 2

Stuart 850 550 83 40

Suburban Park 500 625 15 12

Tarrallton 725 825 2 0

Taylor 275 400 18 15

Tidewater Park 500 425 100 100

Titus 610 550 100 100

Tucker 450 500 100 100

West 500 400 100 100

Willoughby 650 600 10 10

Young Park 650 575 100 100

1 A s stated in Exhibit 3 -A , School B oard Plan filed July 28, 1970.

2 A s stated in Defendant’s Exhibit N o. IS, dated O ctober 8, 1969.

3 L ong Range Plan provided fo r pairing o f Ballentine and Lafayette for

1971-1972.

App. 22

M E M O R A N D U M

Filed August 14, 1970

Remanded to this court on June 22, 1970, with directions,

to prepare and file a new plan by July 27, 1970, we are again

met with an opinion which presents no guidelines to assist

the School Board and the court. Despite efforts by the

district court to obtain appropriate definitions of “ dual

system,” “ unitary system,” “ segregated,” “ integrated,”

“ racially unidentifiable,” no appellate ruling is forthcoming.

Issues such as “ racial balancing” and massive compulsory

“ cross-bussing” were avoided by the majority opinion.

Many express findings of fact were made in the district

court opinions.1 It does not appear that the appellate court

is in disagreement with any particular finding; the dif

ferences lie in the legal conclusions to be drawn from such

findings.2 Indeed, it would appear that the fact-finding

process by the district court is of little or no significance in

school desegregation cases, irrespective of the weight stated

to be given to district court’s findings in the implementing

decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294,

75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083 (1955).

It is apparent from the majority opinion, and the special

concurring opinions of Judges Sobeloff and Winter, that

desegregation or integration is now paramount to sound

1 Beckett v. School Bd. of the City of Norfolk, 302 F. Supp. 18,

and 308 F. Supp. 1274 (E.D. Va. 1969).

2 No significance is attached to the fact that certiorari was denied

(Mr. Justice Black dissenting) on June 29, 1970. The opinion of the

United States Court of Appeals was filed on June 22, 19701. The

petition for a writ of certiorari was delivered to the Clerk of the

United States Supreme Court on Friday, June 26, at noon. The

Supreme Court, faced with a long-established precedent of disposing

of all pending cases by the last Monday in June, denied the petition

on Monday, June 29, 1970. Time did not permit an intelligent analysis

of the problems presented in this case.

App. 23

education principles. Only the special concurring opinion of

Judge Bryan mentions the word “ education.” The seven

teen (17) cardinal principles established by the School

Board are abolished, with Judges Sobeloff and Winter

characterizing them as “ spurious.”

The rejection of these principles and the innovation seek

ing to implement them, wherein children, white or black,

will do better in schools which are predominantly white, is

grounded upon the first Brown decision, Green v. County

School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and

Alexander v. Holmes County Ed. o f Ed., 396 U.S. 19

(1969). With deference to the superior wisdom of the ap

pellate court, it is difficult to read into the cited cases any

prohibition against such principles and the plan implement

ing them. True, race is a factor considered, but in any school

desegregation plan submitted throughout the nation the

issue of race remains of utmost importance. In the Fourth

Circuit we are already required to assign the faculty on a

principle of racial balancing without regard to the qualifica

tions of the particular teacher. W e are forced to assign

black children into predominantly white schools and white

children into predominantly black schools to an extent which

is at least beyond token desegregation.

Not a single word in any of the three opinions filed

by the Court of Appeals mentions the testimony of Dr.

Thomas F. Pettigrew, the recognized expert in school inte

gration cases upon whom the School Board relied in formu

lating and presenting its optimal plan which has now been

rejected. Nevertheless, in the separate concurring and dis

senting opinion of Judge Craven, with Chief Judge Hayns-

worth and Judge Bryan joining therein, in Brunson v. Bd.

o f Trustees o f School District No. 1 of Clarendon County,

South Carolina, ......F. (2d) ....... , argued on the same day

as the Norfolk case, D'r. Pettigrew’s testimony in the Nor

App. 24

folk case is substantially accepted by these three judges

even though the witness did not testify in the South Caro

lina case. Judge Craven’s opinion in the South Carolina

case states that “ judges, in fashioning remedies, cannot

ignore reality.”

Shortly thereafter, Judges Sobeloff and Winter saw fit

to file a separate concurring opinion in the South Carolina

case, severely criticizing Judges Craven, Haynsworth and

Bryan for accepting the Pettigrew philosophy, and dis

counting the testimony of Dr. Pettigrew given in the Nor

folk case.

It is frustrating to think that the appellate court, ap

parently in disagreement as to the legal effect and conclu

sions drawn by the most experienced man in the nation who

admits to being an integrationist, has discussed Dr. Petti

grew’s testimony in a case in which he never testified and,

at the same time, failed to mention him in a case in which

he did testify. One can readily imagine that what would be

forthcoming if a district court in Virginia relied upon testi

mony in a South Carolina case in arriving at its conclusons.

While the Pettigrew philosophy is, for the moment, dead,

anyone experienced in the field will predict that it must, in

due time, be restored if integration is to be successful.

Especially is this true when the legal effect o f appellate

court rulings is applied with equal force throughout the

fifty states. Unfortunately, Dr. Pettigrew and the Norfolk

City School Board are three to five years ahead o f the times.

In addition to the fact that the benefits of sound educa

tion have now been clearly subordinated to the requirement

that racial bodies be mixed, the majority opinion of the

Court of Appeals pointedly states that—

(1 ) Booker T. Washington senior high school must

be “ desegregated” for the school year beginning Sep

tember 1970.

App. 25

(2 ) Faculties in each and every school must be

racially balanced, effective with the school year begin

ning September 1970 in the approximate ratio of white

to black faculty members prevailing in the several

branches o f the school system; to-wit, senior high

schools, junior high schools, and elementary schools.

(3 ) Junior high schools must be “ desegregated” for

the school year beginning September 1970.

(4 ) Elementary schools, to the extent reasonably

possible, must be “desegregated” for the school year

beginnnig September 1970.

There is no ambiguity with reference to the mandate

relating to faculty assignments and it requires no discus

sion. While faculty assignments had previously been made

in anticipation of the approval of the plan now rejected by