Group Exhibit (Exhibit A)

Working File

January 1, 1982 - January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Group Exhibit (Exhibit A), 1982. abb68d02-d492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/96ff6d35-bc57-4df2-b316-485b517d6bba/group-exhibit-exhibit-a. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-) Gcocral popularioo charactcristics

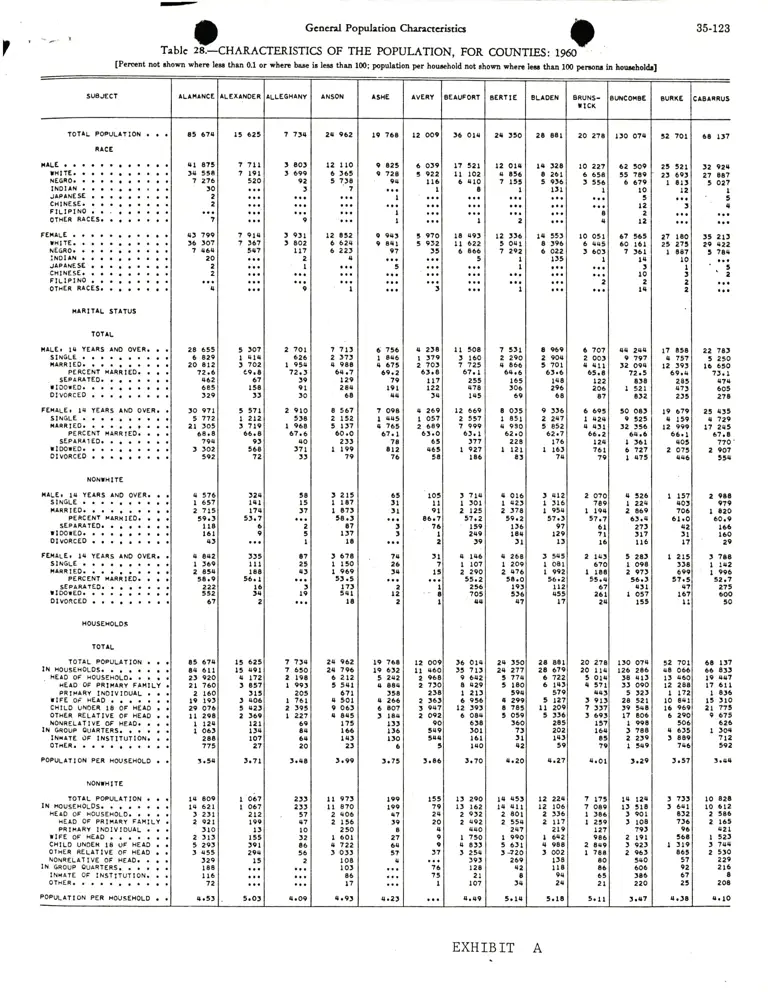

ITablc 28.-CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, FOR COUNTIES: 196o

35-123

7',--r

979

r20

0.9

166

t6o

29

73A

t42

996

2.7

2?'

600

,o

tr7

8r'

4\7

6tt

8r6

tlo

71,

675

626

,04

7t2

,a2

.ag

lP.mnt not rhorrt whcn lcre then 0.1 or rhcrc bu ie ls thrn 100; poputrtion pcr houhold not rhovn rhcn lcet thra 100 pcnonr ln bourholdr]

SUEJECT lLAt{ANcE ALEITNOEi ALLEGHANY ANSON ASHE AVERY BEAUFORI BERTIE BLAOEII SRUNS-

rICK

BURKE cAEArtus

HOUSEHOLOS

IOTAL

TOfAL POPULATION e r

lil HOUSEHOLOS.

. HE^O OF H0USEHOLOT r r r

HEAO OF PRII,IARY FAITILY

PRtX^RY INOTVTOUAL . .

tlFt 0F- HE^O

CHILO iJNOER l8 OF XEAO .

OTHAR RELATIVE OF HEAO .

}iONREL^TtvE OF HEADr r r

INGRoUPOU RTERS.....

INiATE OF TXSTITUTION. .

OfxER. .

POPUL ?tON PER HOUgEHOLO O

NONTX ttE

TOTAL POPULA?ION . .

lN HoUsExOLOs.

HE^O OF HOUSEHOLO. . r r

HEAO OF PRIXARY FAHTLY

PRIX^RY INOIVIOUAL. E

IIFE OF HEAD

CHILD UNOER t8 OF HEAO .

OIHER RELATIVE OF HEAO .

NONRELATIVE OF HEAO. . .

INGROUPOUARTERS.....

INXATE OF INgIITUTION. .

OTHER.

'OT^L

POPULATION

i.lcE

,llLErr.or

lxllEr r e r

NEGIO. o o r

lNOllr{. r r

JAPANESE r r

CHINESE.. r

FtLtPINO . .

OTHER RACES.

FErALt. o r r

IHITE. . . .

NEGRO....

iN0llN r o o

JAPANESE..

CHtNESEo. o

FILtPINO..

OTxER RICES.

XARITAL STAIUS

IOT^L

ItlLEr l$ YEARS INO OVEi. .

SINGLE o

xARR I 80.

PERCENI H^RRtEO. . .

. SEPAMIEO.

rIO0lEOr

ol voRcEo

FEHALEI 14 YEARS AND OVER.

SINGLE .

|llRRlEO......r..

PERCENT HIRRtE0o r r

SEP^R^ t EOr

llDOIEOr

Dt voRcEO

NONIH ITE

xlLEr lta YEARS ND OVEi. .

SIIGLE r

liARRtEOr

PEiCEN" HARltlE0o . r

SEPARATEO.

rlootEo.

oI voRcEO

FEIALET lra YEARS ANO OVER.

SINGLE .

HARR t EO.

PERCENI I{ARRIEOT r O

9E PA RA

'

EO.

r I oot Eo.

ot voRcEo

POPUL^TION PER HOUSEHOLO .

7

rl, 799

t6 ,07

? q64

20

z

2

u

t5 6?s

ol 673

,4 55e

7 276

,o

2

2

28 655

6 829

20 8r2

't2.6

462

685

,29

,o 971

5 772

2l ,o5

68.8

794

, )02

)02

4 576

I 657

2 7t5

59.

'tl8

l6t

4t

4 842

L69

a 834

58r9

222

ts2

67

t5 674

14 611

2t i20

21,760

2 160

19 t9'

29 0?6

rt 298

I 124

I O6t

28t

773

ls 809

l4 62t

,2rt

2 92t

,10

e rl,

5 29t

, {55

,29

188

ll6

72

!.511

ra.59

I5 625

7 ?tl

? t9l

320

7 914

7 t67

947

t ]o?

I {14

, 702

c9.8

67

t56,,

J

'71L 212

, ?19

66.8

9'

968

72

,a{

t4l

l7{

5r. ?

6

9

!r5

ltt

I16

56. I

l6

t{

t5 625

I5 T9l

tt 172

t 857

,l!

, 1106

t q2l

2

'69t2l

llq

lo7

27

I 067

I o57

212

199

ll

r55

,91

294

l5

t.7

5. O,

9

9

2 70t

626

I 954

72.'

,9

9l

,o

2 9to

5]8

I 968

67.6

40

,71,,

? 7r4

I 80'

, 699

92

,

I

7 7tq

7 650

2 198

I 99'

205

I 76t

2 59)

L 227

59

e4

64

20

, 9lt

, 802

It7

2

I

2tt

21,

.t7

47

to

t2

a6

56

2

t8

I5

t7

2I

I

a7

25

4'

,.48

,

9

4rO9

2.1 962

t2 lto

6

'65! ?rE.?

L2 Ar2

6 624

6 22t

ra

2q 962

24 796

6 Ztz

5 r4l

671

4 5o!

9 06'

tl 8{t

l7t

t66

t4,

2'

ll 97'

lt 8?o

2 qo6

2 156

250

I 601

tL 722

, ort

rot

lo,

86

t7

I

7 7t'

2 t?tq 96E

64.7

L29

284

68

8 56?

2 t52

3 tr?

60.o

2rt

I 199

7'

I et'I le7

I 17'

t8.,

a7

t17

la

t 67C

I ItO

I 969

tr.5

17,

5{1

tt

,.99

4.9t

t9 ?6t

9 425

9 728

0u

I

t

I

9 9q'

9 641

97

,

t99

t99

47

,9

6

27

6ra

s7.

{

6 ?t6

I 906

4 67'

69.2

79

19l

44

7 098

I 44t

4 765

67. I

7a

tl2

76

69

,t

,t

,,

?4

26

,$

2

t2

2

t. ?5

sr2)

19 76r

19 612

3 242g 884

,50

[ 266

6 807

t 186

rl,

ll6

lro

6

L2 oo9

6 0r9

, 922

rl6

t

3 970

5 9r2,,

12 009

tl 460

2 968

2 7tO

2ll

2 16l

I 9s?

2 092

90

549

30{

t5,

7i

2tl

20

4

9

9

,7

76

7'

I

I

4 2re

L79

2 70!

6!.8

ll7

122

,4

! 26E

I O57

2 689

5r.o

6t

46t

3t

,t

7It

I

!

I

105

ll

9t

86.7

.?6

I

2

t.g6

16 0r4

t7 521

tt !02

6 {lo

s

I

l8 49'

lt 622

6 866

5

l, 290

l,162

2 9t2

2 r92

4lao

I ?go

4 8r'

t 254

r9,

128

2l

lo7

ll 508

, t60

7 725

6?. I

255

{78

145

12 669

2 557

? 999

6). I

,77

I 927

186

! 714

I rol

2 r25

57 .2

159

249

,9

t. ?0

4.U9

q 146

I lo7

2 290

55.2

255

705

{q

]6 0r4

,5 7l'

9 642

I 429

I 2tt

6 956

12 ,9'

6 064

6t8

,ol

t6l

I$O

24 tto

12 ols

4 Et6

7 tr'

t

a

l2 116

t O4l

7 292

I

I

I

7 5rt

2 290

4 E66

5q.6

165

,06

69

t or5

I 651

rt 930

62. O

2ZA

t l2t

t,

14 45'

t4 4ll

2 801

2 554

2ta1

I 99O

5 6lt

,J2o

269

{2

I

,4

{ 016

t 42'

z t78

59.2

lr6

t6T,r

{ 268

I 209

2 476

5trO

l9l

5r6

2{ }50

2q 277

t 774

5 tAo

39{

{ 299

t 785

, otl

160

7t

ll. 2o

t. ,. lt

.a7

tt

{2

2C 661

lla ,28

0 261

5 116

Itl

t{ 95'

L96

6 022

rr5

! 969

2 904

5 ?Ol

6!.6

148

296

68

9"6

2 247

t 852

62c7

176

I 16'

?o

, .412r 116

I 95q

57r,

07

129

tl

, 5ll5

I OBI

I 992

56.2

ll2

4t9

l7

L2 224

12 106

2"6

2 tl7

219

L 6\2

{ 98E

, oo2

lr8

ll8

9la

2q

tt.2?

5.ll

2a 831

2a 679

6 722

6 tq,

57e

t L27

rt 2oe

5 lf6

za,

202

14,

59

20 2?8

to 227

6 659

, 556

I

ra

I

I

ro ort

6 {q5

, 60,

2

6 70?

2 00,

4 4tt

65.t

122

206

E7

6 69'

I 42{q 4rt

66.2

124

761

79

7 L?t

7 0E9

I lt6

I 259

127

986

2 6ra9

I 7tC

ao

c6

6'

2t

2 070

7El

I l9la

5?.7

5l

?l

l6

$. ot

5.lt

2 lr.!

6?0

I ltt

55. rl

61

2ct

2q

zo 27e

20 llq

t ol{

{ 571

ta{!

,91:

7 tt1

, 69!

I5l

l6{

l!

?t

Iro o?{

62 tO9

5t 789

6 679

lo

)

L2

2

t2

67 )53

60 l5t

7 t6l

l4,

lo

2

ll'

.l.t 24{

I 79'

,2 094

72.'

6t8

I 521

8r2

to o8,

I 521

tz ,36

64.6

I t6l

6 727

I 47'

tra t2{

lr Stt

J 90t

, to8

?9'

2 !91

t 92t

2 96t

540

606

tt6

220

rl ,26

L 224

2 860

6!.4

27'

'L?rr6

t.29

l.rr7

, 2at

I O9E

2 t7'

56.,.lrl

I O57

r55

lro o7q

t26 286

]8 {l'

,, 090

5

'2t28 52t

,9 3qt

l7 ao6

I 990

, ?88

2 2re

I 549

,2 70r

2' 92L

25 60t

Itl,

L2

27 t80

2) 27J

I 187

lo

t,

z

2

t

l7 lt8

u 757

t2

'9r69.4

285ll7t

2t5

,

, ?rt

,641

El2

7t6

96

t6t

I lr9

865

57

92

6?

25

I t57

laot

706

6l.o

42,t

t7

I er5

,r8

699

57.5

47

167

ll

t9 679

{ t59

12 999

66. I

40,

2 07'

446

.5?

4.18

52 701

4e 056

r, a6o

t2 2ee

L L?2

l0 841

16 969

6 290

506

ra 6)5

I 889

746

6a .l17

tr 2lt

2e 422

t 78ra

'5

'2

t2 921

27 Et?

5 021

I'5'{

22 ?At

, 250

16 650

7t. I

474

605

274

25 4r5

4 729

t7 24'

6?.8

770

a 90?

tt{

60.9

156

t

I

I

2 986

979

I t20

32c

6! r,

66 8'

19 4ra

t7 6r

18,

It ll

2t 77

e67

7t

I

to 82t

!,0 612

2 586

2 t65

{21

r 521

, 7s4

2 5rO

229

2r6

3.

208

rr. !o

EXHIBIT A

35-124 _ Nonh Cerolinr

. Teur.e-cnanacrERlsTlcs oF rHE popur.rrroN, FoR couNrrES:rrilt"r.

[Pcrcrot aot rhown rhcn lco thra 0J or rhcn bero la lcg t.hrn 100; popubtion pcr hourchold oot ghom whcn lcar thra 100 prrroru ia hourcholrta]

3U8JEC? clL0ttLL CATOEN C iTERE? CASIELL cATArSA CHATHAX :HEROKEE clrorAN CLAY CLEVE.

L^!o

:OLUHIUS crAvEN CUHBER-

L NO

ilLE.......

lHlfE.rrrol

NEGROrrrorj

l[Otlt{rorrr

tilPAllESEorrr

CHltrElE.....

rll.lPlilo....

otHEricEs...

TOr^L POPULAIION r

ilcE

TE|IALE.r.rr

rHtre. . . .

ifGiOr r r r

INOIII . . .

t TINESE . .

Cxtl{ESEr r r

FtLlrtNo . .

otHEi R cE3.

rlilTrL 3rlTU3

TO'rL

iALEr 14 YEIiS lNo OVER. r

STNCLE r

t{AtRlEO. . . . . . . . .

,ERCER? xlRitEO. . .

sErllrTEo.

tl00rEo.

0lv0icEo

iEl{ALgr lT YgAtS INO OVER.

3INGLE r

li lRtEO. . . . . . . . .

,ERCgNl xlRRlEO. . .

SeplRl?E0.

I lOOrEO.

0l voicEo

NONIHITE

I LEr lrt YEIRS lNo oVER. .

Slt{6LE.........

XIRRIEO.........

PERCEIT XARRIEO. . .

SEP^MTEO.......

rl00rEo.

olYoicEo

FETALZ, t4 YEIiS lxo OVEi.

SINGLE .

lt^tRtEo.

PERCEI{t xlRilEO. . .

SEPltllEO. . . . . . .

rlootEo.

olvoicEo

XOUSEHOLD3

TOT^L

lo?lLPOPUL^TIoN..,

Itl HOU3EHOLOS.

HE^OOFHOUSEHOLOT r r r r

xElo 0F titx^iY F^t{tLY,

titx^iYINOMOU L...IIFE OF HEAO

CxlLD UNOEi lC OF HglO . .

OTXER iELATIVE OF HE O . .

NOiliELATtVE OF HErO. . . r

IX GROUP OU^RTERs.

l|x^tE oF tt{srtTU?roN. . .

otxti..

lotuLlTloil PEt HOTJ3EHOLO . .

NONTHITE

lOlrLl6Pgglll01ror

lN HOUSET{OLoS.

HEAOOFHOUSIHOLOT r r r.

xElo 0F tRI,tAiY FAt{tLY .

till{liY lN0lVlOU^L . . .

lltE 0F Htlo

cxtLo rJNoei lt oF HElo . .

otHEi ieLlrlvE oF HE^O . .

NONiZLATIVE OF HEAO. . . .

lN GIOUP ourRtlis.

ttirl?E OF tNsrrturtON. . .

OfxEi. . . . . . . . . . .

toPuLlttoN Pui xougeHoLo . .

I o, ,,,

L.u,,I zz tesI rccc

l0lc

T9 tt2

49 264

l2 .980

t2 lot

972

to 722

tt 076

? 090

4r6

26A

22i

,0

2t oao

2t 2q!

I t2q

6

t

I

I

t7 122t 267

lt 9to

6t.E

,t9

l.89

,t6

16 ,t,

4 or5

It 7{9

?t.t

261

,7t

t96

I 0!6

,82

,90

36 o9

llt

,t

26

I tzo

t2t

62?

l!.5

37

l9t

2l

lr60

, !l2l

r lorl

7?r I

6s2 I

rel

q9'r Ir 2901

!s7 I

3eI

ll I

rr I

O.rta I

t 12?

,o9

t 244

6e. I

26

t7

l7

t t98

I

I

a ?9t

I 6ot

I t86

2 tO7

r 6t5

I 17t

I

I5

20

2

8t6

t7t

267

ar? ,2

29

225

2l

608

2L2

4t4

6r.9

6r5

la,

t22

0 r.6

!,

?r

t)

, 9981

3 r75l

r srol

r 29?l

r rtl

I rrolr 9!el

9?tl

erl

2rl...t

2rl

,ttal

2 !q4l

476 I

q29 I

{?l

162 I

9 r5l

,56 I

!rl

ro I...t

,"1

c.e2 |

x, 9To

l7 099

It 069

L 927

,0

2

2

rl,

6

l, t4t

12 0rr

L ?37

,5

7

2

2

t2 t40 I

o ogrl

? 9881

6r.? I

160 I

2e6 I

209 I

9 6g?l

r 3761

6 7!11

6e.7 I

22L I

:,.,1

{66 I

7st I

$.oI

)21

,21

2rl

t r27l

,12 I

614 I

,6.!l

12l

rA2 I

,"t::l

2? rorl

7 6rsl

a a27l

eo7 I

5 S?91

9 1231

4 r4el

r16 |,6!?l

661

,57t1

ttD

, t2l

76'

6r6

lol

471

t OO

996

9l

,12

)7

2rt

l.t6

4.6 I

19 9t2

6 {!2

l 58t

4 l!,

6{.6

tl9

629.69

2 8!6

I t2t

I 592

t6. I

77

96

23

z ?7t

t85

l r9l

t7.4

82

26'

,4

to 0r7

, 200

4 tt'

2

ll 912

L9 672

r $rJ

o 24r.1

2eo i, 6991

7 Tt2l

! ?301

2rol

2qo I

r?o I

7ol

9 5!6

9

'98I 744

t clr

9r

L45

, E96

a 298

t17

l18

ll9

tt

9 t7t

t 156

T 7t4,

6 5t2

2 tor

4 t45

ct.7

l12

207

tl

T rlta

5.rl

1,,,""

I lr zceI t ztrlllall

,7 6rt

t4 to9

, q99

I

lo,

2

26 J65

, ro!

t8 279

69.

'526

2 498

4A5

24 2l'

5 559

l7 869

7r.8

297

,67

220

r e?rl

car I

r eo,r

I'6l.rt

rol. aal

,rl

2 22tl

6!9 I

r 2eol

!s.ol

r 12l

zasl

trr:rl

?2 r40l

zo lcal

rs 6791

r ?r?l

r6 6231

23 5061

e rgrl

?201

zcr I

r70 I

rer I

,.rrl

I

" arrl

c zsel

r rtol

r lcol

I?O I

r o25l

a S:clr rrol

r?9 |

c;l

cl

rrl

..u. I

26 ?At

l2

tl .r20

t 146

4 272

-2

t! !6'

I 22'

4 116

t

9 2tO

2 646

6 226

67 t6

162

269

.69

L'6

I 954

6 2r7

66.8

160

I O6e

77

2 668

I o44

L 5t,

37.'

lt5

7l

l6

2 ,6'

7tt7

l' O

59.'

7A

I

26 Tgrl

26 614l

7 olll

6 0601

frt I

c eoal

e oTel

4 6trl

ror I

rTrl

erl

"'::le !o7l

r ecr I

r 160l

ror I

r 2661

r r28l

a rz,a I

126 I

ro? I

arr I

2rl

,.oo I

2!61

l6 ,r5

8 t96

t oo4

162

26

2

2

t lr9

7 9ta7

lr5

,6

I

l4l

56

79

56.O,

ra

2

rr2

,l

80

60.6

E

l6

5

16 fr5l

16 rs5l

4 1951

,9!71qrsl

! o2rl

5 ?r7l

2 SeOl

roo I

lro I

rr9 I

tr::l

t77 I

8eI

arl

.:l

Itr l

ezl

12 Itl

..1I

".ru I

5 670

t 656

t 77t

66. !t

76

t76

65

t 814

I 2rO

I 8!8

66.0

loq

660

.t6

ll 729

6 0r2

t 2t7

e ?94

I

I 6E4

I 058

2 4J9

66.2

79

tre

BA

t )22

544

t85

39. I

t 717

, 048

2 669

I

rr 7291rr eaql

z eral

z ccslrrllz zozl

4 05rl

2 2rlrl

20sl

{rl

rol

,'::l

5 4rll

r ll4l

sce I

r4c I

tzel

r esel

r qszl

r14 I

,rl

6l

231

*... I

oJ5

892

t26

62.6

tll

97!

$4

{

2

65

74

l9

I 69ra.t9t

,t7

,3.l

12

24U

2t

2 ?Ot

2 690

l8

I 9r'

t92

t 116

68. r

2'

194,t

5 526

2 tl8

2 786

,l

I

I 94ra

566

I 298

66.8

25

62

It

!.691

to

30

l8

L5,

lt

E

l2

I

27

to

l$

2

I5

2

ll

2

5 5261! ttrl

r qg,.l

r r70l

r2'rl

t rErlr 9691

t27l

12l

rtl

lrl

,

66 00e

,2 0e,

25 005

7 060

,, 95r

26 245

7 699

2L t12t

t ra70

t, 24t

71. I

582

,t7

175

21 6tr

4 87t

tr 68E

66.4

6q6

2 726

,44

4 047

t 468

2 006

59.

'165

l09

20

4 549

Lq4

2

'gt56.8

,o8

,74

ta8

66 0C8

ct ,22

t7 421

tc oc4lr rorl

rr 925l

2' r23l

ro 162l

carl

t26l

r 241

tao2l

,.r"1

,-r"rl

rr cscl

2 9s3l

e zocl

2rl I

2 ol!l

6 o2el

, rt20I

2!7 |

ro2 I

551

8?l

".c2 |

$a 97!

lt 429

ra 451

to ,41

67.0

t4,

460

15l

t6 ft7

I 5r8

ro 572

64.8

4lg

2 olra l

17, I

2t{ 026

r5 697

7 t96

ll29

t

2{ itt7

t6 l6t

I"8

T25

!

I

s 7r8l

r 66rl

2 S46l

eo.rl

r70 I

r95 I

tol

5 tr2l

I O64t

2 e54l

3?.Sl

2591

'31

"a "rrlolt 72rtl

12 0ra5l

ro 9s?lt o59l

9

'221te 7r2l! rr2l

4e2l

24el

r86l

6rl

".0*l

,, , rrl

16 9501

I $?91

! l20l

,t9l

2 4071

7 0661, ?rsl

260 I

165 |

rro I

!51

o.87 I

,a 77t

19 746

t 907

t, 085

66.

'46!

469

2st

r8 641

, ll!

t, of5

69.9

t99

2 LA2

,l!

!o o?{

2I EsE

8 116

2o

2T

J

t

2l

28 699

19 906

t 606

l8

t2l

6

t

,4

{ 905

I 766

2 828

57.7

273

252

'E

3A 77tl

31 5r5l

11 9831

rl qgcl

r 4s9l

rr 6rsl

2r os{l

7 0rrl

7i7l

, 216l

22rl

! or4l

I,.7I

I

I

17 0091

l6 5721

, 8571t 2731

5e2 I

2 !s8l

6 ooolr azol

cl.tl

crz I

r6s I

26e I

u.a, I

t 4rtl

t !)t

I lo2

5?.Ol

qo4l

eo6l

e8l

146 4t8

8t 4t6

61 2r9

19 402

5t7

rto

l6

6l

29

t4a 4t6

l29 rrr8

[.r7

66 962

47 672

It 288

521

,90

6

40

4,

5t 990

21 169

!2 84ra

58.7

866

87t+

90,

$2 858

7 245

,l lr0

72.6

L 172

, 805

688

12 5q4

4 88q

7 160

37. I

,6t

t66

lr4

tr 807

2 959

7

'lr61.9

667

I ,76

l!l

!, 656

lr ,56

2 500

27 607

3L 525

lq 486

I 674

l0 070

52tt

r! 542

!9 507

f6 006

7 860

7 lr5

169

5 654

lra i9c

7 120

956

, 499

66

, 4r,

!oA2

_ ..O

Gcocrzl Populatioo cherectcrisdo

, , t

gs-l25

Tablc 78._CHA.RACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, FOR COUNTIiIS: Tqd{oo.

[PcE !t Dot rhown whcrc lcrr t]ru 0.1 or tbcn buc lr Iu thu l0O; populrtion pcr hourcbold lot rhorn whcn tan tlra 100 pcrronr h hourholrttJ

suSJECr C URRITUCX O^RE DAVIDSON olvlE OUPLIN 0uiHAii EDGE-

coH!E

FORSYTH FRANXLIN GAS!9N 6^TE3 GiAHAll GR^t{-

VILLE

rOT L POPULA?ION

iAcE

XILE r o

rHllEr r

N€GRO. r

lNOllN.

J P NE SE

cH I NESt.

FTLIPINO

oTxEiRCES.....

FEI{ LE.

txtrE..

NEGRO. .

lN0l li.

J PANESE

CHINE5E.......

FtLtPtNO

oTHEtR^CES.....

XARIT L SI TUS

TOIAL

hlLer l0 YEARS ANO OVER. .

SINGLE.

HARR t E0 r

PERCENT xlRRlt0r o r

5Et tl 180.

rID0rEO.

o I voRcEO

FEt{ t-Er l4 YE RS ANO OVER.

SINGLE.

t{ARR I EO.

PERCENT X^RRtEO. . .

SEPA RAtEO.

r I oorEo.

oMRCE0

NONTHITE

h Lt, l0 YEIRS AND OVER. .

SINGLE.

xAtR IEDr

PERCENT H RRtEO. . .

SEP RATEO.

llDOIEOr

ol voRcEo

FtHlLe' l4 YEAis NO OVER.

SINGLE.

X RRIED.

PERCEN? XARRIEDT T I

SEP^RATEO.

rloorEo.

ol voicE0

HOUSEHOLOS

TOT L

TOIAL POPULATTON . .

lN XOUSEhOLDS.

xErO oF HOUSEHOLDT o o r

HEAD OF PRIt.rARY F I{ILY

PRTHARY INOIVIOUAL r r

IIFE OF HEAD

CHILO UNOER I8 OF HEAO.

OTHtt RELATIVE OF HEAO .

NONREL^TIVE 0F HEADr . o

IN6ROUPOUARTERS.....

INHA'E OF INSTTTUTIONO O

OTBER..

POPUL ?tON PER XOUSETIOLO .

NoNtHtte

TOTIL POPULATIOII r o

lN HousExoLos.

XEAO OF HOUSEHOLD. . . .

HE O OF PRIHARY FAI{ILY

PRIx^RY INOIVtDUAL o r

IIFE OF HE O

CHILO UNOER 18 OF HE O .

OTXER RELATIVE OF HEAO.

NONREL^IIVE oF HEAO. . .

INGROUPOUARTERS.....

lNx^tE OF tNsTtruTtoN. .

OTHER. .

,OPUL TION PER HO{.ISEHOLO .

6 60t

, ,ro

2

'O'I 0r4

2

t 262

2 212

I O{o

I

,.51

2 tre

616

I t70

67. I

,9

tlr

T2

2 t24

400

I 566

6?.ll

,9

,t7

2L

6 601

6 516

I 861

t c2t

240

l' 9l

2 tol

I lo,

7t

65

,t2

2t

669

20,

406

6t.o

,6

44

l4

6t,

161

,92

60. o

22

t9

4

4 r!f

2 066

2 070

476

412

64

t2t

690

550

20

l6

I

It

9rt9

2

2 e25

2 716

l!7

2

t oro

2 79t

216

t

l. l7

19,

5ttll3,

69. O

26rt

,z

226

,19

514

6t.9

,5

t27

46

126

t7

?s

6 t.9

6

to

I

2

t 9rt

,792

I 826

I 99t

2r5

,.2{

I 722

tt9

6t

l{t

6

r97

lsc

29

t,

t6. I

7

23

!

5

l. c,

406

401

ll7

99

l3

t9

t25

90

lo

5

79 49'

26 744

6 0r5

19 802

7{. O

{90

667

2qo

2r ,,rt 002

20 150

7t.l

66e

2 765

421

,9

'rat,{ 97O

{ t6'

5

2

4

oo t|rc

,t t76

T 459

6,

I

2

I

l.56

2 74t

866

t 7to

62.

't76

ll7

to

4.20

2 772

60t

I 7r,

6t. E

205

,{t',7

?9 ra9t

71 586

22 o6t

20 2tt

I 8t7

lE lo,

27 0E4

lO ,91.

917

90?

,64

54!

I 54?

t q56

2 0t5

I 744

271

I tl,

2 961

I 89'

2rq

t9l

144

$7

12a16

5 36'

I ra25

ra 19,

71.5

E8

l9{

5l

6 0ol

t lol

4 rt5

69.7

tl

c24

87

t J69

7

'O4I Orr

!

! ,6'

1 5r'

I OO7

I

lr16

65'

216

407

52 rl

l9

2C

{

6e2

t79

{12

39.t

2l

cl

t2

t6 724

t6 5f,

{ 6tE

{ 216

ts2, tro

t la)o

2 136

99

195

tt4

lal

2 07t

2 07r

4?9

418

6l

)40

656

567

27

.1. 12

TO 270

12 979

, 826

t 625

66r 5

296

418

tol

lr 62r

2 9o4

6 170

60.5

,50

I 8rO

lo5

ao 440

t2 608

? EJO

I

t

ll rro

12 5r8

7

'r2

It lra4

l4 998

, 244

2 895

r49

2 lr9

t 841

, 56'

le l

t{6

ll,

t,

{ 2r8

t 497

2 5E5

6Or !

t89

l8t

2t

4 690

I ,47

z 662

56.6

25'

6ra2

,9

4o 270

{o o79

to 205

? 2t6

969

7 770

l4 78t

6 9?2

,47

t9l

l15

56

,.9r

4.62

Itt 99t

]7 949

ll 2r4

21 059

66.O

I 0I4

t loE

533

42 741

ro 25t

26 00t

60.9

I 3rt

5lll9

I 056

5, 60C

,6 9{2

16 55t

l6

22qt

c

26

5a ,t9

,9 02'

t9 rll

l6

l2

l6

2

9

,6 0ro

,ta t6,

I lO5

7 45t

I 612

, 246

It 224

7 ta2

I 406

I 55?

187

I 480

lo 9rtr 7ro

6 laE,

59.t

646

5r2

L77

Itl 99t

tot la7

,l 22t

26 924

4 lo{

22 r40

,! t4a

l$ 927

2 640

6 lol

al6

) 972

t, ,97

I 9tO

7 r5C

5!r4

290

I ol7

I t90

2 02t

t.77

,4 226

It 216

4 25'

ll lrr

5l.o

655

2 570

270

z7 ?90

tr 4o7

l4 t69

l2

2

26 216

12 6t5

Lt 527

20

o

16 290

o 8ro

lo ?4t

66.O

44la

590

r5,

2t lr4

27 Ar2

I 672

4 999

7t,

, 688

!o 768

? 06l

62'

,02

t15

l6?

t$ 226

5' 649

rt tl4

lt 661

I 4t'

9 642

19 ?0,

lo 259

9rl

t77,,,

224

7 ttt

2 725

rt 404

,9.6

,t0

,22

60

t 62t

2

'804 656

t4.o

ttl

I 2?,

tt2

4. 09

{.91

It9 .r2t

6t 9$2

llt 416

44 9t!

72.6

I 729

I 806

7q,

70 27A

t4 loc

46 lrt

66. O

2 tra2

t 201

I 6tl

l{

9t t2o

74 oot

2{ 45t

2'

2l

6

2

c

16 661

4

'709 0t7

54. t

t 741

2 75a

{r?

90 90t

59 6rt

21 204

l9

7

a

I

t, 66,

4 r7l

8 a$t

60r4

t 0t9

c2t

2t9

q5 ?or

4{ 490

t2 to?

9 452

2 q5t

6 47O

l{ 197

9 619

l -697

I 276

,94

884

,.62

189 428

t8{

'065{ l5tq? 715

6 4t6

40 6{to

60 825

2t 709

5 98t

5 122

? ,4C

2 576

,. rao

2t 7r5

l{ 276t oo9

6 2{2

2)

l4 4?9

? 98{

6 T?C

It

I

28 75t

2A 262

7 r2lr

6 1!6

6t8

t r.ot

to or2

5

'89,29

49'

l!9

lt{

L2 752

12 74'

2"O

2 29t

219

I 786

t 144

t o77

t88

t7

2

lf

o 50?

! 022

6 0t5

6! r7

225

,21

109

9 8rt

2 268

6 lr9

62rT

26'

I tl6

9l

, ar?

I lt7

2 t77

J6t7

la2

40t

t3

, 59t

l.26

2 o8'

!l rO

lal

lt6

26

,.97

5.O0

l2? o?4

6L 727

5' 9l?

7 7!!

l7

4

I

I

63 t!7

56

'29I 777

l4

I5

rl

I

7

q 680I rut

t oo,

64.2

261

2r,

tl

t 66'

I 44a

t 2a2

58.0

Ttt

3t,

AO

q3 629

t 5c9

fl 296

58.5

I 5ral

{ 9tl

91,

le? 0?4

12, 954

,q 7r,,t 7r5

I Ol8

27 6t7

T4 469

l? l16

L 279

I 120

16 628

t6 rol

{ ora6

t 4)7

509

2 q6t

) i?7

! 551

J19

127

69

58

4l r4l

9 55r

,o 290

7r.,

E7{I Ol?

{Et

,91

72?

,.62

qrOS

I 2tra

4 5ll

2 060

e tqe

6

I t20

,9t

,

o 64,

2 L7Z

2 467

2

2

9 ztq

? 2!6

2 270

2 012

2?7

I ?la,

, r90

I 916

l2C

It

l?

t

I O22, o22

I OO9

926

7E

7!4

I 116

l 26

a2

, 060

996I 9r'

6r.2

ll

tot

2E

, 16l

7l'

I 067

62t2

la6

{4t,,

470

37r I

t2

T?

t2

I ttl

orc

!97

57.4

,6

Itt

It

t.oo

4.Ot

6 rar2

t lgt

, 064

127

a t?t

452

I 4Et6t.,

la2

20,tt

l2tal

t lta

l?a

I

6 4r2

6 4t4

I 6r'

t ,21

tto

t ,lt

2 4rt

9r,

102

la

2

l6

256

256

47

47

,t

93

7o

,

2 ItO

629

I 420

66.0

ll

6t

,7

?7

29

{9

t

t

77

27

,17

7,

!r9!

3.st

,, I

t6 24t

a 9r4

I zaa

I

t6 c6t

9 4!t

? tl29

t

ll ot9

, 807

6 76t

6t.a

2t7

t7l

tr8

ll 7t2

, lrt

7 026

t9.9

,t!

I {r4

l3q

{ 526

t 676

2 614

,?.4

l16

llt

It

{ 590

I t2l

2 707

!, lr0

29 7,47

7 5t6

6 7r9

3c7

3 722

lo llSz

, 4t2

505

t ,6t, rr5

l4 72t

l4 400

, ort

2 7t6

)49

2 l9t

5 469

r ll7

,rr

,21

27,

4c

,.92

s 167

39.0

l9?

5ol

t,

ro

POPUL

35-126 North Carolina

Tablc 28.-CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, FOR COUNTIES: 196G-{on.

[Pelc€nt not shown vhcrc leu thu 0.1 or when bsa ir les thu 100; population pcr houhold not shom when lcs than 100 pcmu h houcholdrt

SUBJECI GREENE 6UILFORO x^L I FAX H RNETT HAYTOOO HEN0ER-

3oN

HERTFORO HOKE HYOE IRTOELL J^CKSON J0Hritsl0N -JONE3

rOiAL POPUL TTON . .

RACE

lt^LE..

tHtte..

tecio. .

lNollN.

JAPANESE

CHINEsE.

FILIPINO

olxEt ilcEs.

FEH^LE .

rxttE..

r{Ecio. .

INOIAN.

J^P^NESE....... t

cr{ t NEsE.

FILIPINO

OIHEiMCES.......

t{ousEHoLoS

rot L

tol^LPoPULlTlON...

lta HouSEHoLoS.

Ht^oOFHOUSEHOLOTrrrr

HEIO OF PRIiIIRY FAHTLY r

PRlts^RY tNOlVIOUAL...

tlFE oF ll6ao

cHtLo UNOEi t8 0F tiEAO . .

OIHER ReLAllvE OF HEAO . .

taONREL ftVg OF HfAOe o o r

1,. GnouP oulRrERs.

INXATE OF INgIITUTION. . .

OTHeR..

POPULAIION Pf,R HOU3EHOLO . .

NONTH I?E

TOTALPoPULA?IONrr.

lN |rousEroLos.

XEIOOFHOUSEHOLO.....

xE^O OF PRIH^RY FllltLY r

PR I;.^RY INOMOUIL . . .

IIFE O' HEAO

CHILO UNOER T8 OF f{EAO . .

O'HER REL TIVE OF HEAO . .

NONRELAIIVE OF H€AOr r r .

lN GiOUP OU^RIERS.

INHAfE OF Ir{3?t?UttON. . .

OiHER. r

POPUL TIOft PER HOI,,SEHOLO . .

l. RlrlL st^?us

?OT L

liALEr l{ YEIiS INO OVER. . .

tINGLE .

t{^RRtEo..........

PERCENTIIARRIE0T o o r

SEPlRllEO. . . . . . . .

IIOOI,EO..........

otvoRcEo

FEHlLgr l4 YE nS AIO ovEtl. .

stLGLE . . . . . . . . . .

n^tRtEo.

PERCEN?'{ARRIEO... t

SEP RATEO.

rtoorEo.

0 I voRcEO

NONIHTTE

I^Ler ls YEARS ANO OVEir . .

SIIGLE.oorerrror

liARRlEO..........

PERCEilrt,lAiRtEO....

3ep^RAtto.

rlootEo. . . . . . . . . .

ot voRcEo

FEI{ LE' ltl YEATiS ANO OVei. .

3lx6LE.

tAiRIEO.

PERCENTI{^RRIEOT O r r

sEPARA?EO.

tloorEo.

otvoRcE0

lc 7ql

L66

{ lt5

T 2ll

a t75

o 162

t 2l,

t t2r

I 675

t 27t

6r. e

ll6

l4o,,

t 22t

I 290

, ,28

6r.7

14,

,6t

t2

2 zrt

942

I 2lO

t0.6

35

72

9

z 26t

7qJ

L 272

,6.2

lle

227

l9

g ia2!

8 r2l

I rar6

L24

lr2

I Ot7

, 790

I t82

176

lo,

70,,

t6 741

t6 617

, 69ra

, 4!,

261

2 iz|

6 7!O

, 06,

229

lo4

7t

,t

4. !o

9.79

2{6 520

trt 27t

9t ,67

2{ 700

l7r

4

l$

t

llt

l2t 242

rol 6r7

a6 4t,

l2t

9

l4

t

IE

to ttra

It 646

58 688

72.9

I 9t4

2 129

t o9t

9r f62

Li ,27

60 2t6

66.0

t 2?t

9 641

2 lo8

17 154

{ 902

lo ,72

ta. I

l.92

2 212

,58

t

tl ,16qt 640

L2 t77

lo lr59

I 918

7 E69

16 830

9 427

2 lo2

2 895

,o9

2

'e7

16 l7q

t 458

9 802

60.5

t20

67la

240

246

'202rt 149

69 l2lt

6t tl7

7 941

51 271

aL 227

29 594q 727t rTr

I 501

6 C7o

.{5

!o9!

,6 956

2t 969

12 84'

t5 859

zr5

2i 0t7

l, 6f7

t6 057

2A2

I

It 295

, tt9E

12 00c

65.6

470

t86

204

t9 )95

4 4r9

t2 170

62.7

6?[

z ro)

2tt

,2 46tr

tt 681

6 069

, 505

,s4

4 277

Lt 221

7 6??

41,

78t

607

L7s

9 to9

, f42

t 289

tr. I

,re

,t8

60

9 407

2 886

S rlo

t6.c

4a2

I l16

7'

18 956

,7 9r4

tr o4rt

12 589

I 435

lo {87

2t 558

tl r25

700

I 042

?27

,I'

4. 12

t.20

s8 216

2' 899

t7 287

6 4t5

187

2

t

2t rt?

L7 526

6 617

186

5

I

,2

16 745

t 692

l0 Et9

6[.7

509

2 0!o

204

{8

47

l2

ll

t

9

l6

I

16 t58

5 002

to 5r7

65ol

,te

496

145

216

2t2

,?4

280

094

509

54S

219

5r2

t, 421

Lt 277

2 735

2 152

,04

| 779

t 004

, ra66

272

l16

I l6

,o

, ll94

I 520

2 lll,

56. r

176

169

22

t 069

L 241

2 271

15.8

26ta

5t8

t,

I 00q

160

804

,.62

T.g2

,9 7ll

le 466

ta 999

{76

to

I

20 22t

t9 8t8

,91

l2,

t

t4 5tl

2 519

lo 19t

70.2

255

L' 622

, o89

I 990

7J.'

l{14

,tl

160

I 3t7

264

27t

62

t64

60. I

to

o,

{

894

926

202

l7l

lt

lrs

275

202

l2

68

c6

2

l.o9

,9 7ll

t9 429

lt 26f

lo ,4,

920

a 22A

t, lJl

! 506

2Ei

242

192

90

,21

l2t

178

55.5

lo

t5,

,.!o

,6 16l

17 49'

16 to2

967

I

2

I

It 670

L7 692

974

I

I

2

12 44t

2

'779 047

72.7

144

laoq

120

l! 695

2 ,91

9 22t

67.'

242

I 66{

217

2*7

407

t7.t

,!

t1

1

66'

l5!

t7c

,r. I

4t

lr6

ta

I 969

r 846

,t2

,92

120

277

t5t

417

a7

l2t

i2rt

,6 t6l

,3 829

to 708

9 5l'

I l9l

3

'6!ll 542

4 752

46ll

trtl

2tL

lo,

708

t., 5

t.61

22 716

lt lr5

4 617

6 498

o tl,

I 199

2 tA7

,a.o

224

q75

t4

lt 5al

{ 68r

6 900

2

22 ?LE

22 otj

, t65

{ 82S

5t7

ll ol5

3 tt9lr 162

,96

659

7 275

2 !91

4 592

6r. I

209

218

7t1

7

'70I 84'

4 665

61 .6

235

9?0

9t

l! 400

l, 229

2 7t9

2 4r7

262

I 895

5 208

t t22

283

l7r

tr]

lr8 l

t 844

l.7l

2 291

59.6

t7f

144

,6

49ra

l6t

I{.1

o. e7

16

"6

t l2r

, 492

, 929

707

a 229

t rt70

{ oo2

73'

I

4 767

t 3at

I Or9

6r.,

126

158

49

t 09,

L2l

, 099

60.8

168

605

68

16 156

l, 70,

, {66

,180

286

2

'986 159

t 296

l8{

65t

604

49

9 ,94

3 971

I 620

I {96

124

I t25

, 692

2 401

ll,

t2t

,64

,9

2 t56

97,

I t72

!5rl

a2

9t

tl

2 681

907

I 4rl,r.t

lra,

tD

t2

o.!,

9.54

5 763

2 Ar7

t 66JI t94

2 906

I 667

I 241

I 917

566

I 257

65 16

t2

72

22

2 04'

427

t 29r

51.2

,8

,16

9

?59

2tt

ra2'

56.0

26

99

2

696

262

406

lrro!

l9

25,

5 ?65

t 761

..

'2l.62

170

I lr4

I 7rt6

t 29'

56

I

2 4r5

2 415

1.69

4tz

t7

!4C

el5

744

2l

T

!.76

,.l e

62 126

,O larT

24 983

t 446

I

I

I

I

20 741

{ E67

It 065

72.6

,2r

62C

Irl

22 77'

4 621

t, 272

07. I

$61

2 321

,57

c2 526

6t E97

17 55r

t3 9t4

I 617

l, gt?

20 tlr

9 067

6{9

629

rloo

229

,.5'

,2 0a9

26 qo6

, 677

I

I

2

, 2eo

I lt9

I 985

!o. l

lr5

149

,7

t t67

t o5l

2 0r4

,6.7

200

{50

,2

ll trJ

l0 969

2 506

2 207

299

I 607

, 869

2 7i4

19,

l6q

tr9

25

or!a

6 497

2 219

t i97

61.5

lo5

l7 780

s 952

E 08'

r7l

69{l

64tl

?r

,o8

16,

290

57.t

2o

6

'9'I 647

4 oJl

6!. I

120

I 828

7 957

170

699

I

I

72

209

2tl

ll

tr6

t09

,o9

t7.6

25

6!

t5

17 780

t6 776

I 4?6

{ lrl

,4,

t ,47

t tr4

, o2e

I lao

I OO4

lo9

t95

I TraO

I 7rO

!59

tt2

27

2r6

6t1

ra59

L7

lo,

7

7,!r

{.E2

62 9J6

JO 970

2ra I l5

6 849

4

,l 966

29 692

7 267

2

2

I

I

I

2

20 906

5 e?t

t4 2t7

66. I

,74

597

201

22 L70

4 6l'

tq 5ro

6 5.5

518

2 77q

25t

q o22

I 524

2 298

57. I

t6?

t70

to

4 q64

l 4'

2 462

55.4

27t

t99

60

62 916

62 r71

16 659

I5 tq8

I 9lt

It o78

22 79'

0 202

E'7

r6t

26E

97

l4 t29

r4 052

2 999

2 649

,49

I 972

t 564

, 167

,5t

77

22

,5

,.76

o.69

lr oo5

5 320

2 gral

2 57l.

5

5 4t5

2 89t

2 569

o

,414

I 056

2 2rl

6q.8

t19

26

a5

420

2t

I larz

5r5

856

t9.9

60

t5

871

96.7

c2

I?E

, 5s6

8lt I

2 2t2

62.8

ll oo5

to 974

2 5f'

2

'262o5

| ?77

4 t6l

I 2lO

9l

,r

,l

5 17'

t r{2

I 005

926

7'

7to

2 020

I ,26

59,r

,t

I t{O

4. !'

!r.t2

,.rul.HARACrERrrr:;; Tffiffi , lo* .o^r,"r.,,r2""

[Percent not ahown where les than 0.1 or when bae is lerc thal r00; popuJation per houeholtt not show! whcre les tJla.n 100 pcmD! in hourctol&l

35-t2?

SUBJECT LEE LENOIR Ll NCOLiT [c ooreLL x cor'r xAol sot{ IIARTI N ,{ECKLEN.

AURG

ITITCHELL HONt-

GO14EiY

t{ooRE Nlsx

IoTAL POPULATION

R^CE

f{4L8.....

rHtTE. . . .

NEGRO. . . .

tNOl lil . . .

JAP NESE..

CHtNESE...

FILtPtNO . .

OTHER R^CES.

FEIALE....

rxtTE....

NEGRO. . . .

lN0llN r o r

JAPANES€ . .

CHtNESE...

FILIPINO..

OTXER R^CES.

IiARITAL STATUS

rOTAL

X LEr ts YEARS AND OVER. r

SINGL8.

I{ARRtEOo

PERCENT XARRIEO. . .

SEPAR TEO.

rloorEo.

o I voRcEO

FEXALET II' YEARS ANO OVER.

SINGLE.

x RR I 80.

PERCEN' HARRIEO. . .

SEP RATEo.

r I oorEo.

o I voRcEo

NONTBTTE

llllEr l4 YEARS rNO OVER. .

SINGLE.

tlARRtEO.

PERCENI taARRtEDo r r

SEP RATEO.

rloorEo.

oIvoRce0

FElllLEr l4 YEARS AND OVER.

SINGLE.

t{ARR I EO.

PERCENT }TARRIED. . .

SEPARA TEo.

r I o0rEo.

ot voRcED

HOUSEHOLOS

TOTAL

TOIAL e6Pgl-1716i1 . .

IN HOUSEHOLOS.

HEAD OF HOUSEHOLOo r . .

. HEAO OF PRIHARY FAI{ILY

PRIXARY INOIVTOUAL I 'IIFE OF HEAD

CHILO UNOER tE OF HEAO .

OIHER RELATIVE OF HEAO .

NONREL TIVE OF HE O. . .

INGROUPOUARIERST...T

INXATE OF INSTITUTTON. .

OTHER..

POPUL ItON PER HOUSEHOLO .

NONIH ITE

TOTAL POPULAIION . .

It{ HOUSEHOLDS.

HE O OF HOUSEHOLDI O ' 'HEAO OF PRII,IARY FAI,IILY

PRIHARY INoMDUAL..

IIFE OF HEAO

CHTLO UNOER t8 OF HEAD .

OTX€R RELATTVE OF HEAD .

NONRELATIVE OF HEADT T ItNGROUPOUARTERS.....

INHAiE OF INsTITUltoN. .

OTHER. .

POPULATION PER HOUSEHOLO .

25

'6

6 758

2 295

6 lot

69.7

170

282

80

9 2t7

I 77U

6 218

67,3

25t

I 064

l6t

t 651

578

982

t9. r

e?

8'

l6

I 889

It96

I 065

56.Ia

t45

290

,6

l! O7l

LO 2Ui

2 B2l

tl {8!

lo 4l(

r osq

26

'6126 136

7 146

6 454

692

5 5rO

9 476

r 8r8

!66

203

l2t

77

,.69

4.36

t 90,

3 8s7

l.44

I 159

r65

816

2 205

I

',8l5q

46

I

,8

5' 27

l? o?l

5 tor

ll 28r

66.l

551

g9{

lE'l

t9 2r(

q 67(

ll ?5(

5l.t

8li

2 46(

,5(

? o?e

2 00!

, 90{

55. I

6tlI Ocl

lrr

26 5rt

16 20

r0 ,,

28 721

l7 20

rt 5r'

3' 276

52 I50

l5 871

L2 278

I 595

lo t27

19 465

8

'61I 024

2 426

2 050

t76

6 06!

2 llc

, 6a{

59.a

,9t

262

3l

,.8t

4.

'a,

2r a72

zt 525

4 864

rl l9o

7Lq

2 951

6 216

4 9fB

5t6

t47

142

205

26 I

? 721

2 4rr

6 9rt

7 t.l

l5l

26\

7t

to 2l!

2 021

7 00t

6E.!

l9:

I O8l

le(

9B(

40!

t2t

5r. l

,(

52

!

I O?(

,N

,,6:

52aa

6a

l4!

l2

l{ 2l

12 5t

170

l{ 59

LZ 771

I 82i

2t 8l{

28 6t6

7 708

i L't

3Jt)

6

'0€9 9rtl

4 5t7

169

178

r25

52

t.7

5,20

t ize

,518

676

614

62

45t

I 467

857

t5

t

2

c

26 7qi

l, l2t

l2 451

661

tt 52,

12 9r!

7O!

26 742

26 552

7 rl9

6'7]6

5t,

5 975

e 225

,8rt

201

190

98

92

I 95{

2 t7l

6 448

72.4

l2l

25t

82

9 672

I 867

5 60l

68.2

15,

I O45

r59

rl2t

l{2

25t

59.6

l0

,25,

47b

L2e

262

54r 8

It

72

t5

1.6,

I J76

I t67

,tr9

291

58

2?O

455

t25

l8

I

9

,.92

r$ 9t

! 2T:

I rtr(

, 58:

5S.:

,i

lBl

4{

5 42(

I t5t

,651

67.r

7t

55:

6:

loq

oc

rE

3r.:

lol

.25

59

57 tl

1

l9

7 rao

726

1'

7 521

7

'71t4:

l4 er5

rq 8!6

4 172

, 8ot

,71

,r@

5 068

2 t70

97

99

85

l4

,.56

298

295

EI

6'

20'4,

9t

70

e

J

2

I

1.55

l7 2l

6

'012 t97

t 425

60.7

7l

201

70

6 to2

I 595

, 920

62.2

7A

7lo

7t

t9

t6

20

2

I

5i

l{

26

tt

I 680

t 626

,l

6 5t7

I 468

67

t7 2t7

16 288

4 462

4 or4

ll28

, 496

, 266

2 909

l5t

929

2{

905

! r65

12,

120

l4

26

t

2r

,2

,f

,

,

,.5t

z7 tt9

lt t42

6 ?r8

6 60l

t

2

Lt 797

6 8.rl

6 95)

,

I t6l

2 556

5 488

65.6

215

261

56

, 6ta5

I l5r

2 tll

59.5

164

l17

25

a 92t

2 060

5 647

6!.'

,0,

t ro7

89

{ oo9

I 249

2 2tat

55.9

252

479

42

27 Lt9l

2? 016l

6 {761

5 8rr2l

614 I

4 er2l

lo q2r I

{ s45l

,8r I

lorl

891

r4l

,1. l? I

,rr""l

D c6S|

2 6651

2 t-ttl

29ql

I 80!l

5 76Sl

2 e57l

275 |

92 I

7s I

r{l

5.o' I

t9 250

5 879

r2 t5'

6r. I

,. lt,

99r

2201

z?2 Itt

lro 16l

98 617

,l 427

6l,

l4

t

t6

t4l, 95o

to6 547

,t 274

8l

l!

l7

t

l5

86 490

t9 664

6'

'O571.2

2 tzL

2 167

I r5J

98 605

19 580

65 lra t

66. I

t 772

rl 597

2 257

22 665

5 554

l, 2la8

56.5

2 r7l

, 509

f54

272 tlt

266 62'

76 477

67

'069 571

58 092

9' 984

,r 62J

6 047

5 4E8

t 174

4

'14

t.41

66 947

65 719

t6 47ra

l, 897

2 577

to 046

2' 859

- !, tol

2 259

L 22A

r95

Io,,

9.99

t, 906

6 855

6 612

2L

7 ort

7 0!l

l7

5

,r"aal

r, 8s? |, ?!01

, 4761

2s8 I

, 068l

I Beel

2 roTl

7el

rel

,il

'"rl

til

,il

:::l

I

T ?65

I 269

l rr5

69.6

t{z

l4T

t7

t 06t

r o8{

, f6l

56.4

32

567

{9

t6

6

3

2,

l5

I

9

Ir {o8

I lo7

6 866

2 220

I

9 fol

5 9!0

2 160

4

I

2

6 ort

I 6t6

4 1,9

69.6

lol

t96

l.{

6 407

I f38

4 2r2

65.7

122

780

57

r8 4081

rB 2631

4 s84l

.. 39! I

4e! I

t t47l

6 55!l

2 E50l

22r I

rc! I

eel

AOI

!.?4 I

I

i 3:sl

e20 |

s28 I

e2 I

6!2 I

r 8341

t o6cl

col

28 I

ll

".;: I

I 2tt

l+20

74e

60.7

4g

6t

2

l.at?

llra l

792

55.9

57

t7e

6

t6 7t,

l7 80,

l,128

4 64f

,o

It 9ro

t, 870

5 02t

,5

2

2

tt 9!5

t 2e7

t tzg

68. I

249

,86

l rlr

2 8!51

96e I

r 6e5l

59.8 I

128 I

r48 I

221

,2251

862 I

r sr?l

56.' I

22rl

505 I

arl

,"rrrl

!3 9?61

r s56l

s 6501

r 216l

7 29rl

12 5361

s 77el

4so I7t7l

414 I

!4! I

,.65 I

"rrrl9 6001

2 2571

r 9041

f5, I

r t7l I

I 25rl

2 5rr I

206 I

r15 I

42 I9'I

q.25

|

lr t02

2 9r7

8 )O0

5r. f

,?r

I 67t

214

61 004

29 854

l7 991

lt 8ro

.t2

I

,l llt

rt 7rt

l2 J65

!E

2

2

19 r2f

5 462

ll 006

67.'

452

6!t

220

20 777

4 606

ll 261

6f.e

596

2 6!8

272

6 alt

2 .196

4 001

,8.6

]00

272

62

7

'282 208

4 t{9

56.6

,73

.891

80

61 002

60 498

lt ,o5

l, 762

I 56'

ll 607

22 r,l9q

9 eoa

944

504

264

240

24 2aO

24 097

{ 810

{ 29'

317

, ,88

9 825

5 556

518

It,

A9

! r94

ll4

5.Ol

35-128

tl

North Ceroline

Tablc 28.-CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, FOR COUNTIES: l96G-Con.

[Prrcent Dot rhowa rhcrc les thrn 0.1 or vherc beso ir les th.n l00i populetiou pcr howhold not shom wherc lcs tha! IOO penoD! in hou*hol&]

IUEJECl NEI

HANOVEi

lloitx-

AIIPYON

oNSLOl ORANGE PAr,rLlco PAS0UO-

tlNx

PENOER PEROUI-

IIANS

PERSON PIT? POLK RANOOLPH

?OTAL POPULATTON .

iAcE

114LE.........

lHlTE. o

NEGRO..

lNOllN .

JAPANESI

CHINESE.......

FtLtptiro

OlHEiRlCESororr

FEtllLE........

lHl tEr r

tlEciO..

lNOllX.

r,APlNeS€

CtrlNESE.......

FtLlPlNo......

oTlrEiRcts.....

XlRlTAL S?AIUS

?OTTL

l^LE| ls YEIRS NO OVER. 'SINGLE.

tt RR I E0 . . . . . . . . .

PERCENT I{^RRIEO. . .

SEP R^TEO.

lloorEo.

0IvoRcEO

FE!{^LEr l4 YEARS ANO OVER.

SINGLE.

II RRIEO.

. PERCENT I,IARRIEO. . .

SEP^R TEO.

ll00reo.'olvoRceo

ttoNtHttE

lllLEr lO YEliS INO OVER. .

S!NGLa.........

iAiitEo..........

PERCENT I'ARRIEO. t .

!EP^R.Are0.

I t00tEo.

0lvoicEo

FEIALE' lT YE iS ANO OVEi.

tlllGLE .

t{liR tEo.

PEiCET{T t^RRtEO. . .

3ErlR^?EO.

! l 00rEo.

0IVORCCO . . . . . . . .

. HOUSEHOLOS

TOT L

' ?OtAL POPULIIIO.{ . .

lNHOU3EHOLOS.......

HE^O OF HOUSEBOLDT I I I

HE O OF PRIXARY FAI{tLY

,ltr.lRY lNOtVIOU L..

IIFE OF HEAO

CHILO UNOEi !6 OF HEAO .

OTHEI REL TIVE OF HEAO .

NONREL^'IVE OF HEAO. . .

IXGROUPOUARTERS.....

ItiH^?E OF INSTITUTIONT .

OTHER..

POPUL TION PER HO{JSEHOLO .

NONIHIIE

POPULIIION PER HOUSEHOLO r

7t

,tt 22t

2' O't

I Ot7

,2

7

9

lll

2l

,7 tt9

26 691

lo 771

t6

4

ra

4

L2

2t l:17

, 676

t6 !62

?t r0

670

7\?

152

26 t7a

, LA2

l7 267

64r2

I 266

t 12,

60{

!l 691

I 79'

I 492

61.4

187

,r6

70

7 ttr

I t6l

I 96!

t{. !

739

t ,6,

lll,

7t 742

70 3r2

ao 9r2

17 99t

2 9r7

lr.7!,

2t 398

9 858

I 4lt

I 2r0

244

966

,.

19 99e

t9 ?66

t 274

4 294

980

2 746

6 701

4 260

76'

2t2

52

t80

7tl2

t7

t.7,

26 All

t, 297

4 798

8 500

I

lr 5l4

4 9t6

t 59'

t ,lo

2 70t

5 2{r

61,2

209

29t

66

t 7ro

2 205

t 288

60.6

259

t t58

79

4 85ra

t 850

2 820

58.1

t66

t59

?5

ra 966

I 505

2 85'

s7.5

207

580

26

a6 81t

26 qt6

6 095

t tl72

62t

T tll

9 ?68

3 6le

4$'

t55

2lo

125

4r !4

l7 099

16 845, rr2

2 909

2t1t

2 292

6 804

4 298

299

254

149

lot

t.l4

a2 706

49 tlo

41 4tq

t a88

t6

r0

l6

2t

t,

,, 196

2g 270

T 62'

5'

l5r

27

,7

,5

,6 098

t7 618

17 701

4e.O

l4o

,o6

'{5r

20 4oo

a 701

t6 289

79.8

,r6t 2ll

199

4 099

2 orr

I 9!8

47 o9

lll

88

q2

2 E17

66'

t 908

65.9

It2

26t

,8

a2 706

65 569

t7 t85

t6 266

lE7

t3 090

27 706

5 02{

,84

l7 tt7

trl

t? 006

,.62

tl 022

9 t7\

I 968

I 75t

217

I 556

, ltlT

t 828

205

I 648

70

t t?c

T.76

T2 9?0

22 624

l? 56r

t or5

t

6,

I

t7

ao ,46

t5 204t tr6

2

9

l5

16 614

7 zto

t 9ta

71,7

t90

,41

le5

t{ 459

, 605

E 998

62.2

,20

I 417

219

t tt{t 142

t 820

58.4

96

t2t,t

, t9l

881

t 89f

t9.,

L7'

,65

,2

12 970

,7 8rt

lo 7c,

9 22'

t 540

E O9o

LZ 7t5

t 080

I t6'

I lre

269

4 870

t.5l

t0 205

lO 094

z 159

t 916

ztat

t 499

,76r

2

'802i,

lrl

45

66

4r68

9 850

4 870

, l2l

I 749

T 980

, rl8

I 862

tlr,

8q5

2 169

6t.8

la6

lol,r

, rtl

626

2 225

67.2

75

427,,

9?O

,20

ti1

6r.5

20

t2

tl

I 079

,t?

628

t6.2

t7

L26

8

I 850

9 817

2 519

2 252

2r7

I 971

, [75

| 7t7

rrt

t,

t,

t.9r l

t 6tt

, 605

682

622

60

ta97

l.r.7

I OO2

77

6

6

5.29

25 610

12 462

? 59t

$ 861

I

t

2

It 168

7 9tO

t a5t,

o

t ,E6

2 19'

t 7{6

6E.5

l6t

,lr

ll8

I t22

I 918

I 849

64ol

247

t t72

16,

, 049

I 056

t 796

59.9

124

165

87

,416

! otd

I 882

t5. r

l6t

416

64

2' 610 I

24 116 |

6 86rl

t 9E7l

890 I

5 rrgl

6 670l

t 72ll

4o5 I

6rq I

80 1

?r4 I

r.6r I

,"rrrl

e614l

2 2SOl

r e26l

r24 Ir 4901

r5r2l

2oscl

2r8 I

515 I

16 I

q99 I

s.r? |

l8 508

9 l4o

4 745

{ ,68

5

I

9

'68g a57

{ 498

I

2

7

J 962

I 899

t 79L

6r.6

149

2"t

49

6 209

I 416

t 87r

tt2,)

184

829

!f

2 5t6

975

I s85

,7.tt

9'

lt5

ll

2 Tlll

77t

l' 45

,6.4

tr4

laoS

l,

l8 508

lE ,90

4 6t'

I llo

4t,

) 196

5 5ll

, 716

L74

tl8

?i

,9

! r99

6 906

8 798

I 8!6

I 664

174

t 2r5

t 2t2

2 )9q

tl9

lo8

?7

ll

t

{.79

9 l7a

4 5r'

a ,99

2 154

4 645

2 tl?6

2 169

, o4l

472

2 009

66rl

7l

l{o

20

, l6e

65'

2 02t

6!r8

86

466

27

L 276

4q7

7'L

56.9

,l

70

s

,oa

,51

7r4

97.6

59

190

It

9 t78

E 994

2 ,8E

2 lro

279

I 768

! l{r

I 586

lo9

184

68

ll6

lo77

c ,o,

I 222

908

7q7

tlr

602

I 6I2

I 025

75

8l

68

l5

T.65

I

26 f9{

l, o9r

6

'804 628

80

2

I

t,,0,

8 5!l

t 678

72

I

t

E 589

2 4t8

5 801

67.5

t4l

264

62

8 978

2 052

5 865

65.l

l8l

966

95

2 ?{q

I 020

I 599

56.

'75

lo9

l6

2 85t

879

t 617

56.7

)2

,rl

22

26 5E4

26 ztt.6567

6 0r7

310

, 2?5

9 826

4 265

)oo

t6l

120

4l

,.99

I tlt, I

9 1661

r srol

I 67el

r?r I

r 16ll

,9921

r 9801

rsr I

lr? |

ro8 I

'l

t.o6

|

69 942

,, 7!O

19 ll8

l4 404

I

6

I

t6 212

20 I40

16 o6t

4

t

2

2r ?t6

6 979

l, 9r5

64. O

56 !,

636

2r6

2rr ,06

6

'20l4 49,

59.6

916

t 201

foo

a lot

2 967

4 686

57.8

{ro6

tlt

7t

9 582

2 789

5 13'

tf.8

729

I 5lO

lro

69 9q2

67 4rl

17 ort

tt 166

I 665

t2 572

20 55r

t2 0r0

L 267

2 5rl

144

2 t67

!o 96

,o 484

,o $4t

6

'823 567

8lt

, 956

lr 729

7 727

655

,5

l9

l6

{ aa

lt

t 516

T 805

7rr

t 8?9

5 167

7ll

, 9t8

I 06l

2 686

68r2

75

140

tl

4 282

669

2 707

6r.2

8l

6r2

7*

lt !95

LL 276

, f90

2 848

5q2

2 ta29

, 665

I 597

195

tl9

75

44

t. rl

I q2,

I ,42

)r2

254

,8

tg2

4r,

t67

T8

tl

7L

lo

4.ro

,95

I

47t

r7l

266

,6.

'2?

,r,

{64

ll2

2rto

11.7

2t

85

7

6l

,o 4tl

27 892

2 551

,l 044

2A !77

2 55t+

lo

2

21 020

4 89t

L5 422

71.4

tt7

,49

158

22 074

{ ot7

t5 706

7t.!,

It9t

2 075

260

I 66'

629

9r4

57.4

7a

7t

t

I 62E

4r9

I ool

6t.5

loo

176

L2

6t 497

6r l15

t7 45'

l5 966

r q87

l{ 299

2t l4'

? 590

650

t62

221

l4l

t.ro

, t28

{ 966

!, 190

I 022

l6E

794

I 806

I 069

127

lt12

tlt

24

I

ra.t9

35-r29O

Gcncral population Charactcrisdo O

Tablc 28._CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION, FOR COUNTIT.S: I96&.Con.

[Pcrtcnt not rho*rr whcre lerr thrn O.l or vhcra bu ie las thrn 100; populrtion per hourchold not ehosn wherc lcar thra l@ pcmu tn Lourctolrtr]

SUBJECI i I cHtroNo ROBESON ROCK-

IN6HAII

ROI N RUIHER-

FORO

slxPsoa{ SCOTL N0 sr t{LY sloKEs SURRY sflr{ TR NSYL

vlNtA

?OI L POPUL TION

RACE

XALEroo.r

IHITE. o r e

liEGRO. . . .

lNotlf, . . .

JAP N€S€ . .

cxtNEsE. . .

FILIPTNO . .

OTHER R CES.

FEi^Le....

rHtTE. . . .

NEGROT o. r

INOIAN . . .

J P NESE..

c,ilNES8. . .

FILIPTNO . .

OTHER R^CES.

x^RtrAL STATUS

rOTAL

^NO

OVER. .X^LEr tg YE RS

SINGLE...

I{ARRIE0. r o

PERC ENI

SEP RATEO.

ilOOiEO...

olvoRceo . .

FEH^LE. t4 YIARS ANO OVER.

SIhGLE .

t{lR R I EO.

PERcENI xARRIEo. . .

sEpaR tEo.

l!tOrEo.

o I voRcE0

NONrH trE

HILE| t4 YE^RS IND OVER. r

SINGLE.

xlRRtEo.

PERCENT HARRtEOT o r

5E'A RA 1EO.

r I oorEo.

ol voRcto

FEXALE, IT YEIRS AND oVERo

SINGLE.

nARRtE0.

PERCENI I' RR:EO. . .

SEP^RrTEO.

I I OOiE O.

0tvoRcto

xousExoLo3

rOT^L

loTlL POPULAIJON r r

IN HOUSEHOLOS.

HEAO OF HOUSEHOLO. . . ..

HE O OF PRII'iARY FA}IILY

PRlx^RY tN0lVlOUlL..

IIFE OF HEAO

CXILO UNDER 18 OF I{EAO r

OTHER RELAIM OF HEAO r

NONREL^TIVE OF HEAO. . .

INGROUPOUART€Rg.....

IN{ATE OF INSTTTUTION. .

OTHER..

POPUL^TtON PER XOUSEHOLO .

NONTH ITE

TOI^L POPULI'ION . .

lN xousExoLos.

HE^O OF HOUSEHOLO. . . .

HE^O OF PRII{ARY FAHILY

PRTHARY INOtVIOU L..

TIFE OF HEAO

CHILO UNOIR IE OF XEAO .

OIHER REL^IM OF HelO .

NONRELATIvE OF HEIO. . .

tNGROUPoU^RTERS.....

INXATE OF INSTTTUTION. .

OTHEN..

'OPUL TTON PER HOUSEHOLO .

,9 202

19 047

t! 286

t 7)7

l6

J,

20 lt,

lo o89

6 0r7

25

I

I

t

I

t2 620

r 516

I 57!

6?.9

274

!94

l4ll

t! 855

2 9t4

3 6t8

6r.6

405

I 9tO

2r'

, 458

Ll7

I 928

55.8

lt7

170

2t

I 73'

997

2 020

5!.8

207

697

4l

ll 627

lr ,16

2 556

2 221

tar5

t 5?O

ra 197

2 723

l6l

5lt

445

65

t9 202

,6 5t4

lo !92

9 277

I ll,

7 699

t, 698

6 t23

400

6e8

500

r8t

,.71

4.26

E9 lo2

{l 4ro

L7 717

t2 562

l, lot

I

9

ta5 672Ir 8r5tr 694t, l17

t

,

26 0r9

I 646

16 44'

51. I

6t4

749

20r

28 tarlt

7 ql5

L7 076

60. I

96'

,615

,28

l, 835 Ir 28{l

s o85l

58.4 I

464 I

42' I

6!l

re 126 I

4 616lI 5r5l

56.4 I

??r Ir s25l

,"r::l

8e o20 I

r9 90e I

rs r5, I

I 146l

r0 6st I

16 01, I

16 09r Ir 2!21r o82l

t4r I

?4r I

tr"t:l

52 r5E I

9 9891

9 rc6 I

s4, I

6 0481

2! lrr Irl 092 I

srE I

re2 I

2r8 I

r54 I

3.:221

69 629

,, e85

26 9r'

7 0q5

7

lt 6T4

28 024

7 604

9

6

I

2' 22t

t 548

16 ?46

72. L

qr5

6ra l

288

2'

"O4 7)5

17 t86

67.8

6r9

2 918

q7l

{ 295

I t85

2 680

62.4

154

le7g,

4 906

l.44

2 80ll

57.2

22'

664

94

ttl 672

L4 622

, )90

2 970

420

2 ,0,

5 218

, )9?

,14

50

2

48

69 629

69 2s5

ll 44,

t7 614

I 809

l5 rl5

2' 06l

r0 658

774

,?4

l{7

227

!.56

4.!l

62 817

{o 604

,, 751

6 8r7

l2

2

42 2l',5 rr2

7 080

I

5

2

2,

I

I

82 817

8o 681

2' 820

2l J2r

2 492

ts 725

25 252

tt orl

85'

2 lf6

t 20f

9r,

28 6ra5

6 89'

20 577

71.8

50l

8'E

)r6

,0 592

5 628

ao 822

68. !,

760

,612

5ro

4 450

t 594

2 )7'

!7rE

186

22a

5t

4 70t

trD

2 6ra,

56.2

2E9

696

oc

l, 95{

lr 215

, 2tr5

2 747

{96

2 05t

4 q52

, o8t

t76

7,9

lr9

420

,. 19

u.o7

st o9t

l5 22r

I ?rl

lo 904

7lr5

22t

{44

rTO

,.52

5 r.oo

t ,58

I 214

I 060

150

775

t 9?l

I ll7

8t

r2

25

l7

0.cr 1

22 000

19 42'

2 572

2

I

2' O9l

20 268

2 819

2

2

16 748

, ,42

I I l'ta

56.6

,50

2 004

248

2

4' O9t

44 509

12 614

LL 552

I Ot2

lo oo4

Ira ?6la

5 7lO

t57

592

470

ll2

I 52t

554

90,

59. I

6t

62

9

I ?7r

496

988

95.6

It5

259

,5

rat ot,

21 8r!

t{ 9tI

t {50

{ta9

I

2

19 607

4 647

10 fo?

66.0

298

32L

l12

16 2rr

, 684

lo 49t

64.6

,99

I 9r'

t2'

zra 2o0

l4 952

I tol

4{4

t

2

t l17

I 6t,

, o44

59.5

lEt

204

l6

5 tr4

I 6q'

,193

57.7

267

630

o6

{t ot,

47 ?et

tl 8?2

lo t6,

I OO9

9 277

l7 36ra

t 592

la?c

2r0

129

l8 150

l8 lo?

, ?61

, 400

,61

2 6['

7 zLl

{ 262

224

4'

l6

27

tol

.02

4.61

o

25 tt,

L2 2L7

6 ?8t

5 05?

,79

7 457

2,'8

4 ?tO

64. I

195

272

64

L84

a 099

I OO5

99.7

,49

I 150

lr0

t2 966

7 2t5t rlT

,9'

25 18'

24 91,

6 026

5

'946f2

4 254

9 79t

4 ttt

2r7

270

lt7

lr,

t ool

I 209

I 618

t4r6

tl2

lll,

ll

, ,69

I 08t

I ?50

51.9

222

5r,

ra

ll l06

lo 916

2 r97

I 9{9

2tl8

L60

4 591

2 646

142

2lO

r0o

llo

4.1'

q.98

{o E7'

t, 952

t zco

to 2r,

7!r!

l7{

,78

9t

l5 0t4

2 882

to 416

69. I

256

I 619

157

I 264

laoo

tl9

6!.8

40

55,

I 4!9

,{4

868

60.t

64

2lt

l2

20 07t

t7 89{

2 170

2

7

20 AOO

l8 4Ba

2 >12

I

2

t

40 87'

rao 21,

It 686

lo 654

I Ol2

9 565

r, 5r2

5 1!4

276

660

l6c

lt70

4 q97

4 488

I 069

920

149

729

I 68'

919

8t

9

t

{

o.20

I r{4

22 tt$

lt 147

9 996

I tll'

g

2

7 7A2

2 0ro

5 461

?o.2

126

219

72

7 856

I 555

5 456

69.4

rlo

779

67

ll 167

lo o49

I rlt,

2

66t

20l

,80

96.9

L7

80

7

652

2t8

t77

55.9

2t

2t

o

22 ll.a

22 t3g

5 905

5 50'

402

{ 9rl

? 65t

, to6

t,,

lt6

llra

z2

2 26i

2 266

4rt

.aoT

ll

t2l

9ol

58t

20,,

5.21

,.75

4t 205

I

I

I

t6 264

t 906

tt 6t4

72.6

217

427

ll7