United States v. Falk Brief on Motion to Quash Subpoena

Public Court Documents

September 7, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Falk Brief on Motion to Quash Subpoena, 1971. 129ca463-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9746e1c5-1881-42c7-8a79-aa810c64ad67/united-states-v-falk-brief-on-motion-to-quash-subpoena. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

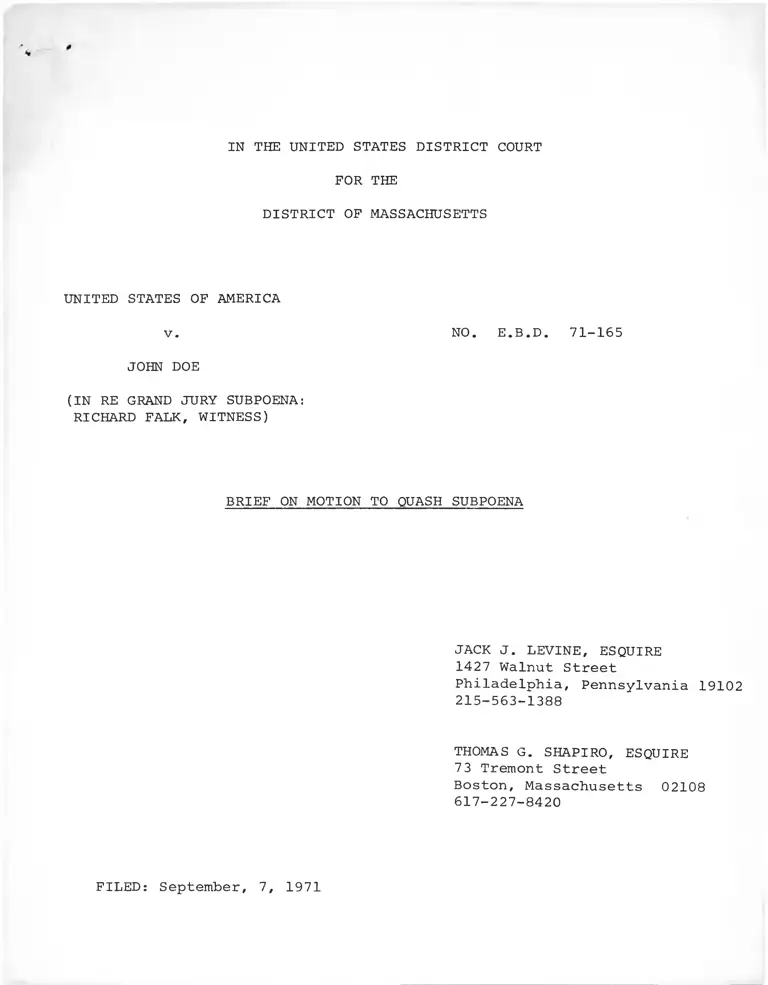

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

V. NO. E.B.D. 71-165

JOHN DOE

(IN RE GRAND JURY SUBPOENA:

RICHARD FALK, WITNESS)

BRIEF ON MOTION TO QUASH SUBPOENA

JACK J. LEVINE, ESQUIRE

1427 Walnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102

215-563-1388

THOMAS G. SHAPIRO, ESQUIRE

73 Tremont Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108

617-227-8420

FILED: September, 7, 1971

TABLE AND SUMMARY OF CONTENTS

PAGE

I. STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED IV

II. PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

III. SUMMARY OF THE RECORD BEFORE THIS COURT ON THE FIRST

AMENDMENT ISSUE

A. Introduction

B. Richard Falk's scholarly activities relating to the

Vietnam War are uniquely dependent upon his access to

information which would not be available to him but

for the extraordinary trust and confidentiality which

has attached to his past professional activities.

C. Notwithstanding his other professional roles^his role

as a journalist, including television other media

activities, itself is central to his professional activities

and public value.

D. An equally significant scholarly function flows from his

sustained and frequent advisory contacts with members

of the United States Congress, and the confidentiality

and trust attached thereto.

E. His role as a legal scholar, and as an expert legal

consultant and witness with regard to judicial proceedings

involving the legal aspects of the Vietnam War depend

crucially on his confidential and intimate familiarity with,

and access to,the subject matter of this grand jury investi

gation, and his public value to our judicial system in this

capacity is arguably more important than whatever marginal

value he may serve as a grand jury witness.

11

13

F. Movant's mere appearance before this grand jury, coupled

as it is with no showing of compelling and overriding

governmental interest, will provide no benefit to the

grand jury and will irreparably interfere with his own

professional activities and similar activities by others. 15

a. Activities such as Movant's, in all pf his

abovementioned roles, provide an indispen^ble

and unique public value, which value is premised

upon absence of governmental intrusion. 15

b. A condition precedent to Movant's mere appearance

should be a showing by the government of compelling

and overriding national interest. 17

IV. ARGXJMENT 19A

I. The Professional And Public-Educational Activities Movant

Seeks To Preserve Are Protected By The First Amendment

Against Governmental Intrusion. 19a

A. Movant's journalistic activities, because they are

primarily concerned with the subject matter of the

Pentagon Papers, fall within the scope of Caldwell v.

United States. 434 F.2d 1081(1970), cert. granted

91 S. Ct. 1616(1971). 20

B. Notwithstanding the applicable scope of the journalist

privilege. Movant's activities as a professional

scholar and author are themselves cognizable under the

First Amendment, and, as such, are entitled to the

parameters of protection established by Caldwell, supra. 21

C. Movant's professional activities are protected against

this grand jury's intrusion unless and until the

Government demonstrates a national interest so compelling,

overriding, and unique to Movant that it outweighs the

public worth of his own and similar protected pursuits. 29

1 1

D. In the absence of compelling and overriding

need. Movant may not be compelled to appear

before the grand jury at all, as there is no

testimony he could give which would not be

within the bounds of the protective order

required under the rule of Caldwell, supra. 41

II. Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States, 251 U.S. 385 (1920)

and/or 18 U.S.C. Sections 2510(11), 2515, 2518(10) and

3504 Require The Government To Affirm Or Deny The Use Of

Wiretap And/Or Other Electronic Surveillance Upon The

Allegation By A Grand Jury Witness That Such Surveillance

Has In Fact Occurred 45

III. CONCLUSION 46

111

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

Richard Falk is a nationally and internationally known

scholar and author whose studies of the nature and legality of the

Indo-China War are authoritative in the field. His recognizedly

pre-eminent activities as journalist, author and lawyer, as they

relate to the war, are uniquely and crucially dependent on the trust and

confidentiality which has attached to his efforts to secure accurate

and complete information, as well as write, counsel and consult with

others. The excellence of his work would not have resulted, nor will it

continue, but for these relationships, and that excellence has at once

been the source of, and impetus to, the consultation with him by others.

Therefore, the first issue before this Court is:

WHETHER, CONSISTENTLY WITH THE FIRST AMENDMENT, A

PROFESSIONAL SCHOLAR AND AUTHOR-JOURNALIST MAY BE

COMPELLED TO APPEAR AND TESTIFY BEFORE A GRAND JURY

WHERE THE UNQUESTIONED EFFECT OF HIS APPEARANCE WILL

BE TO INFRINGE UPON AND DESTROY CONFIDENTIAL ASSOCIATIONS

AND RELATIONSHIPS WHICH ARE INDISPENSABLE TO THE QUALITY,

ACCURACY AND CONTINUED EXISTENCE OF HIS WRITING AND OTHER

PROFESSIONAL PUBLIC-EDUCATIONAL EFFORTS

In addition, Richard Falk has moved to quash his subpoena on

the grounds that he has allegedly been the object of unlawful wiretap

and/or other electronic surveillance. The second question is therefore:

IV

WHETHER A GRAND JURY WITNESS HAS STANDING UNDER

18 U.S.C., SECTIONS 2510(11), 2515, 2518(10) and

3504 AND/OR SILVERTHORNE LUMBER CO. v. UNITED STATES.

251 U.S. 385(1920) AND ITS PROGENY, TO DECLINE TO

APPEAR BEFORE A GRAND JURY ON THE GROUNDS THAT HIS

SUBPOENA, OR THE QUESTIONS TO BE PROPOUNDED TO HIM,

FLOWED DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY FROM UNLAWFUL WIRETAP

AND/OR OTHER ELECTRONIC SURVEILLANCE.

V

I.

PRIOR PROCEEDINGS

On Monday, August 16, 1971, Richard Falk was subpoenaed

to appear before a federal grand jury then sitting in the District of

Massachusetts. This subpoena was made returnable on Friday, August 20,

10:00 A.M. On the morning of August 20, Professor Falk filed with this

Court a motion to quash this subpoena, at the same time requesting that

his appearance be stayed pending the filing of affidavits and brief, and

argument thereon. A stay pendente lite was granted by this Court on

August 20, and the matter set down for argument on September 10, 1971.

This Court also provided that such affidavits as the witness and the

government saw fit to submit would constitute the record in this case,

without further live testimony being required.

1. Professor Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor of International Law

and Practice at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International

Affairs, Princeton, N.J. He also is a Research Associate and Member of the

Advisory Committee of the Center of International Studies, which is an

adjunct to the Woodrow Wilson School. He is a member of the Bar of the

State of New York and of the International Court of Justice, the Hague,

Netherlands. His Vita, as it is directly relevent to the issues here raised,

is attached hereto as Exhibit A(l).

II.

SUMMARY OF THE RECORD BEFORE THIS COURT ON

THE FIRST AMENDMENT ISSUE

A.

INTRODUCTION

The record upon which Movant will rely consists of a series

2

of twenty-six affidavits, both his own and of others. His

affidavit is of course the keystone of the record, and reference to it

will be made in conjunction with references to those of the supporting

affidavits which either testify to the verity of the Falk affidavit or

lend particular credence because the affiant's own experiences and

concerns parallel those of Falk. Because Movant functions in a variety

of professional roles, all of which we contend are protected by the

First Amendment, there will of necessity be some overlap in the summation

of the record. Briefly stated, his contentions are threefold: First,

2. These affidavits have been collated, paginated, and filed with the

clerk of the Court, to be made part of the record in these proceedings.

Each affidavit has been given a letter designation, and this record has

been paginated serially. References to this record will be made by the

name of the affiant, the exhibit letter of his affidavit, and the page

number of the reference (e.g. Falk, A, p.lO). Where relevent, the pro

fessional capacity of the affiant will also be summarized.

It should be noted, as the Court is already aware, that these affidavits

were prepared with great haste, and that because a number of those solicited

for affidavits were on vacation (particularly members of Congress) Dr. Falk

was often unable to immediately locate them. See Falk, A, p.22. This

brief has been prepared on the basis of those affidavits in hands by

August 31, 1971. In the event that more material arrives, it will be filed

with the Clerk by September 10 and referred to during oral argument.

- 2 -

that his professional performance, particularly as it relates to the

same subject matter covered by the "Pentagon Paperŝ " has uniquely

depended upon the use of information lathered from confidential sources;

Second, that others believe the absence of such sources would severely

damage his professional effectiveness in this narrow area; and Third,

that mere appearance by him before this particular grand jury would

unquestionably inflict the kind of damage referred to. See Falk, A,

pp. 1-2.

B. Movant's Scholarly Activities Relating To The Vietnam War

Are Uniguelv Dependent Upon His Access To Infoirmation Which

Would Not Be Available To Him But For The Extraordinary____

Trust And Confidentiality Which Has Attached To His Past

Professional Activities.

The work product of Richard Falk's activities, particularly

as they relate to the Vietnam War, are, under any measurement standard,

truly extraordinary. Continual testimony to this exists throughout the

3

record, and his own affidavit impressively recites the s\am total of

these efforts. The record is replete with testimony that this uniqueness

3. E.g. Richard J. Barnet, Co-Director of the Institute for Policy

Studies in Washington, D.C.: "He is one of the country's outstanding

students of international law and the leading expert on the legal aspects

of the Indo-China War. He plays an almost unique role as unofficial

advisor, scholar, and journalist, combining a comprehensive knowledge of

law and a sophisticated understanding of the relevent facts surrounding

United States involvement in Indo-China." Barnet, B, p. 29

- 3 -

is at once the sourcefor, and impetus to, consultation with him by other

4

professionals, and that, as Movant himself recites, at length, these

consultative and advisory roles are central to his professional standing.

4. "We...have continually called upon his seemingly unexhaustible services

as a resource pegsgn, as program advisor, and as a consultant in points

of intemaltional/ domestic law, particularly as they relate to the Vietnam

War. His access to a wide variety of materials, studies and documents

contribute jtowjLrd his rare eclectic approach to contemporary problem

solving. . ./Hi_s/writings and lectures are sought after by individuals and

groups nationwide, in the Congress of the United States and at international

conferences." Knopp, C, p. 3CL "His services as a professional consultant

and resource expert have been essential to our own understanding of issues

...". Mea.cham, D, _p̂ 31. "Professor Falk is one of the very few experts

in such /War relate^ mattery to whom we have wished to turn." Lauter, E,

p. 32 . "His contributions /to the conferences and seminars sponsored by

the Fund for New Priorities in Americ^ were perhaps the major reason for

the impact of our efforts." Meyers, F, p. 34 . "He is one_of 24 elected

Council members of /the Federation of American Scientist^ and is a

valued source of advise to us; his high, unique, and unblemished reputation

makes him a "special asset". Stone, G, p. 35-36.

- 4 -

There can be no doubt that, as Movant testifies, his

5

extensive writing and lecturing on America's involvement in the Vietnam

war has depended upon his access to real facts, or, he describes, "the

real state of affairs". Falk, A, 3. "In essence, this scholarly role

has depended upon getting at the real facts wherever possible". Falk,

A, 3. That the range of his contacts in ferreting out the truth encompasses

6

a wide variety of political opinion is supported by the record, as

is the fact that this unique ability to deal with both sides of the

political spectrum has enhanced his reliability amongst those who consult

7

him.

5. A partial catalogue of these writings is set forth at Falk, A, pp.4-5,

10-11. See also Falk Vita, Exhibit A(l).

6. E.g. Harold Feiveson, presently lecturer in the Woodrow Wilson School of

Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, and formerly an

analyst for the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency:"Professor

Falk is one of the very few persons I know of with wide contacts both among

vigorous opponents of American defense policy and among present and past

members of the government who apply a more marginal and restrained criticism

to American foreign policy. He therefore brings to his writing and advice an

unusually broad perspective and an intimate familiarity with the positions

and attitudes of several diverse groups, a capacity that I and many of my

colleagues have found very useful." Feiveson, H, p, 39

7. "As a particular example, I was importantly influenced, while in the

Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and engaged in policy analysis of the

Non-Proliferation Treaty, by Professor Falk's articulation of the special

attitudes of the underdeveloped countries toward international security".

Feiveson, H, p. 39 . "He has been an invaluable consultaht and source of

ideas, not least of all because his many contacts provide him with a deep

and broad knowledge of world affairs that enables him to be an excellent

judge of the merits of attempts by scholars to understand and interpret

current issues and events." Thatcher, I, p. 40

- 5 -

Central to the scholarly effort of seeking information about

the War, and central to the First Amendment claim here made, is the

need for absolute confidentiality and the trust and confidence built

thereupon. Two of the supporting affidavits before this court, one

written from the vantage point of book editor and the other from that of

a noted scholar and published author, focus directly on Movant's beliefs

in this regard:

Sanford G. Thatcher, Social Science Editor, Princeton,

University Press: "Many books today that deal with

matters of immediate national and international concern

could not have been written at all without the use of

information obtained through private interviews and

other confidential communications and this is perhaps

pre-eminently the case with investigations of the Vietnam

War and related issues which Professor Falk has chosen as

one of the primary focuses (sic) of his professional re

search." Thatcher, I, p. 40 . (Emphasis supplied).

Ronald Steel, journalist, author, teacher, and Member of

the Council on Foreign Relations: "In order for either a

scholar or a writer to conduct his role with integrity and

efficiency, it is absolutely essential that he feel free

to discuss matters of public interest with various individuals

who may, for various reasons, not wish their remarks to be

quoted publicly. The quest for truth relies upon trust and

access to information which may not be generally available

to the public. Not uncommonly, individuals, whether in

private life, government or business, seek to conceal wrong

doing, and it is the role of the responsible scholar or

journalist to ferret out the truth. To do so he must often

seek sources of information which would remain closed to him

were he not able to guarantee that they would be entirely

confidential." Steel, J, p. 41 • Emphasis supplied.

8.

Falk's own affidavit focuses repeatedly on this need for confidentiality.

- 6 -

8. At p. 3: "My understanding of such complex and controversial

current developments has depended upon having access to confidential in

formation and to various individuals in and out of government who would

not be able to discuss this sensitive subject matter with me if they

thought that I might be compelled to disclose it in the course of an

investigation of this type"; "Again, my sources of information depended

really upon an assurance on my part that the discharge of this professional

role would not be subject to the sort of scrutiny that is involved in

a proceeding of this type whose focus is upon how information relating to

the war was acquired." "Here, too, my capacity to report truthfully and

effectively depends upon maintaining contact of a confidential sort on

all sides."

At pp.4-5 Falk lists twenty (20) examples of his recent writings which

have "relied upon confidential information to inform its presentation."

At pp.9-10: "...my role as journalist and participant in community

affairs has depended on similar access to confidential information relating

to the war"; "As with any journalist, my success has depended on building

up and maintaining confidential sources of information and of convincing

editors that I have things of value to write about," citing examples and

and listing at pp. 10-11 examples of journalistic writings.

At p. 10, with explicit reference to the subject matter of this

grand jury: "I was invited (but declined) to participate_in an informal

Congressional conference devoted to /the Pentagon Paper^ and have been

asked by the weekly magazine Commonwealth to do a book review of the

Pentagon Papers. American Report, and several national newspapers and

magazines (New York Post, Philadelphia Inquirer, Time) invited my comment

on the disclosure of the Pentagon Papers when they became public. In each

of these settings my value as an interpreter of the news depended on my

access to information and on my reputation for confidentiality."

Other assertions of this need for confidentiality and trust, with

specific examples, can be found on virtually every page of Falk's affidavit.

- 7 -

as do virtually all of the other affidavits furnished in support of

9this contention.

9. E.g. "His professional contributions depend crucially upon his access

to confidential sources of information. Because of his reputation for

discretion he is able to talk regularly with individuals whose cooperation

is essential to an informed professional understanding of the crucial

problems with which Professor Falk is concerned as scholar, lawyer, and

journalist." He has been able to play his "invaluable role...only because

of the confidential character of the sources he has developed." Barnet,

B, p. 29 . (Emphasis supplied)

"On the basis of intense involvement in the fields of international

relations over the past fifteen years, it is my firmly held judgment that

responsible scholars and journalists must have access to information

where representations that confidentiality concerning the source of this

information is of paramount consideration in eliciting it." Mendlovitz,

K, p. 42 . Emphasis supplied.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of the need for confidentiality,

and the extraordinary trust which Falk enjoys because of his ability to

preserve it, were his successful efforts to arrange the participation

in American television debates of the Paris negotiators for the Democratic

Republic of Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government. See

Teicholz, McGhee, and Cook, L, M and N, at pp, 44-51 ; and sections

dealing with Falk as journalist, infra, pp. 9-10 . Likewise, with regard

to his successful efforts to arrange private talks between these Paris

negotiators and Members of Congress. See Falk, A, pp.12-13.

- 8 -

C. Notwithstanding Movant's Other Professional Roles, His

Role As A Journalist. Including Television And Other

Media Activities, Itself Is Central To His Professional

And Public Value.

As is more fully discussed infra, p.20-21 a quite common

and natural occurrence is the welding of journalistic activities with

10

scholarly pursuits. All of the considerations of confidentiality and

trust discussed above apply with equal vigor to these journalistic

pursuits, recited in detail at Falk,A, pp. 9-11 (including list of

publications), 14 (with particular reference to television and radio,

and 15 (journalistic activities in the explicit context of the Pentagon

Papers).That Falk's contributions as a journalist are considered important

among his peers is illustrated not only by the extent to which the media

publish and utilize his work, but also by the recognition by his

colleagues that such efforts are an important role to which attaches

11

considerable public value. It seems fair to say that Falk's ability to

10. In addition to Falk's affidavit, several of the supporting affidavits

illustrate the role of journalism in the larger context of an academic

career. See, e.g.. Steel,J, p. 41:"Like Professor Falk I am both a scholar

and a journalist, a combination of careers which is true of a great many

people at a time when it is necessary for professional expertise to be

conveyed to the widest possible audience."

11. "Professor Falk's journalistic contribution on matters of world

peace have in my view been of immense importance to the American public

over the past four years." Mendlovitz, K, pp. 42-43 .See also, Teicholz,

Cook, McGhee, M, N, L, at pp. 44-51 .

- 9 -

to deal in confidence and trust with Vietnam veterans and North Vietnamese

and NLF negotiators, and journalistic efforts such dealings produce,

parallels the kind of contribution to public dialogue that Earl Caldwell

12 '

has made respecting the Black Panther Party.

In a more generalized sense, this can be said of virtually

all of Falk's journalistic efforts, relating as they do to a subject of

great controversy and the understandable reluctance of many of his sources,

particularly government officials, to make revelations which might later

come back to haunt them. Falk's articles, regarding such topics as war

crimes and individual responsibility therefor, and prisoners of war, of

necessity involve him in tracing the decision making process as it occurs

within the government. Informed judgments at these matters "must deal with

what responsible governmental officials knew at a given time what they

told the public and Congress, and how they acted as a consequence."

Falk, A, p. 17. It should be noted, most importantly, that the revelation

of this decision making process is the single most important aspect of

the Pentagon Papers and that informed commentary on the Vietnam War would

be markedly dependant upon the kind of information contained therein.

12. These contacts, particularly with veterans who have revealed to

Falk information relating to alleged war crimes (See Falk, A, p. 3, and

Lauter, E, p. 32 ), are precisely analagous to Caldwell and the Black

Panthers. Both kinds of contacts and transfer of information are infected

with the fear that confidences, once broken could quite probably lead to

some fomn of official retribution.

- 10 -

D. An Equally Significant Scholarly Function Flows From

Movant's Sustained And Frequent Advisory Contacts With

Members Of The United States Congress, And The Confidentiality

And Trust Attached Thereto.

Members of Congress, their respective staffs, and the staffs

of the respective Congressional Committees have in recent years placed

increased reliance upon the academic community in virtually all areas of

legislative concern. Nowhere has this been more true than in the field of

foreign policy, with virtually continual committee testimony being heard

and counsel solicited and given. As is the case with his other contribu

tions, Movant's activities here are remarkable. These activites are set

forth at length at Falk, A, pp. 8-9,12, and 17-18, and have included

publication of writing in the Congressional Record, confidential counseling

with members of the Senate, counseling with Congressional staffs on

matters relating directly to Vietnam (e.g. implications of SEATO treaty;

status of Geneva Conventions on Prisoners of War), testimony and writing

for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, arranging confidential contacts

between Senatccsand Paris negotiators, and counseling with Senators on the form

and/or advisability of particular pieces of legislation.

13. The confidentiality which attaches to such activities has arisen

in another context in these proceedings. See In Re Leonard Romberg, Witness,

No. . To the extent that they overlap, counsel for Professor Falk

specifically adopt those grounds set forth in support of the motion to

quash filed by Dr. Rodberg.

- 11 -

All of these efforts have been carried out with the utmost

attention to ascertaining and presenting accurately the facts about

the war as they may be known to Falk. One example in particular

illustrates the manner in which the gathering' of information, ituch

of it confidential, plays a subtle yet crucial role in this process:

"I was approached by Senator Harrison Williams

of New Jersey in early 1971 to prepare an advisory

report for him on whether to support an effort to

curb the power of the President in the area of war

and peace. The value of such a report depended on an

assessment of the war in which Presidential decisions

were made in the context of the Vietnam War. This kind

of information is precisely the sort covered by the _̂4

Pentagon Papers." Falk, A, p. 18 (Emphasis supplied).

The extraordinary subtlety and delicacy of contacts between academicians

and Congress is set forth in detail at Stone, G, pp. 35-39 . Such

delicacy is implied throughout those portions of Movant's affidavit

15dealing with Congressional contacts.

14. ^-pp. 13-14 infra,with regard to this decision making process.

15. Nowhere is this more apparent than with regard to channeling

information from Paris negotiators to American officials. See Falk, A,

p. 19. Also of significance is the indirect effect such information may

have on legislation. See Crown and Standard, 0, pp. 52, 55 » detailing the

affiants' belief that Falk's contacts in Paris contributed to the

passage of the "Mansfield Amendment".

- 12 -

E. Movant's Role As A Legal Scholar, And As An Expert

Legal Consultant and Witness With Regard To Judicial

Proceedings Involving The Legal Aspects Of The Vietnam

War Depend Crucially On His Confidential And Intimate

Familiarity With And Access To The Subject Matter Of

This Grand Jury Investigation, And His Value To Our

Judicial System In This Capacity Is Arguably More Important

Than Whatever Marginal Value He May Serve As A Grand Jury

Witness.

Let it first be said that "there are very few, if any, American

international law specialists who are able and willing to play this role.",

16Falk, A, 16, and his value must be measured in this context. Falk's

activities as legal advisor or defense witness is detailed at Falk, A,

16, and has centered primarily upon gathering, making available, and

testifying in open court to the character and legality of the war policies.

This activity has of course supplemented his other legal writings on the

war, as well as his work with the Lawyers Committee on American Policy

Toward Vietnam (See Crown, and Standard, 0, pp. 5 1-56.) and their wide

distribution of material to members of the bench and bar. It has likewise

been explicitly relied upon in several instances, most notably in this

judicial district (Falk, A, p. 17).

At the heart of this activity is unimpaired access to

facts:

"Let me stress that the inference of illegality relates

closely to the actions and intentions of leading policy

makers and that such an inference can be reliably made

only by access to just such information as was contained

- 13 -

in the Pentagon Papers. An informed judgment about

illegality must deal with what responsible

governmental officials knew at a given time, what

they told the public and Congress, and how they

acted as a consequence. To cut someone (sic)like

myself from such information is to reduce my

capacity to base legal conclusions on the best

available evidence. This information would no longer be available

if I am to be required to testify as to whether and

how I gained such information, from whom and when.

Unimpaired access is needed to assure my professional

competence. Falk, A, p. 17. (Emphasis supplied).

16. The value of this availability is set forth in the affidavit of

Paul Lauter, Executive Director of the United States Servicemen's

Fund: "In our work with the U.S. Servicemen's Fund we have come into

touch with servicemen or veterans who have, or believe they have,

committed war crimes or other violations of international or military law.

In pursuance of our corporate purpose to seek the well-being of such

serviceman and women, and in the public's interest in achieving justice,

we have sought out expert scholarly and legal advice to determine the

most appropriate course of action for such persons to pursue, consonant

with their consciences, mental health, the relevant law, and the

public interest. Professor Falk is one of the very few experts in such

matters to whom we have wished to turn. However, given the ambiguous

character of many war crimes statutes and precedents, the sometimes

uneven application of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, and the

highly emotional character of these matters in the United States today,

absolute confidentiality and trust is essential to GI's and veterans

desirous of examining possibly illegal activities, in Vietnam and

elsewhere, in which they participated. It is my judgment as Executive

Director of the Fund that such GI's and veterans would be extremely

reluctant to discuss their cases with scholars who had been or were to

be interrogated by Grand Juries, regardless of what they did there.

Work on behalf of United States military personnel would thus be

significantly limited and, it may be, the causes of establishing clarity

in the legal obligations of military personnel and the public's interest

in seeing justice done would be, too."

- 14 -

F. Movant's Mere Appearance Before This Grand Jury,

Coupled As It Is With No Showing Of Compelling And

Overriding Governmental Interest, Will Provide No

Benefit To The Grand Jury And Will Irreparably____

Interfere With His Own Professional Activities And

Similar Activities By Others.

a. Activities such as Movant's in all of

his above-mentioned roles, provide an

indispensable and unique public value,

which value is premised upon absence of

governmental intrusions.

Those portions of the record which testify to public value

necessarily rest on the premise that governmental intrusion, including

the mere appearance under compulsion before a grand jury, will diminish

or destroy public rights. It is well to note here the assessment of such

dangers necessarily involves a balancing process, and that to the extent

that public value of a given individual's contribution may be large,

the balance is affected accordingly. Also noteworthy here is the fact

that the publication of the subject matter of this grand jury inquiry

has already been held to be of public value and non-injurious to the

national security. New York Times v. United States, 91 S. Ct. 2140(1971).

To the extent that a grand jury witness was not a direct participant in

whatever criminal activities attached thereto, the need to protect his

public value is accordingly enhanced.

None of the countless experts who have studied the Vietnam War

have contributed more to scholarly and public dialogue than Richard Falk.

- 15 -

Repeated and continual reference to this fact is made in the affidavits

before this Court, and it is made notwithstanding whatever partisan

17

views various scholars and journalists have expressed and with particular

18

reference to cited examples.

The right and need for the kind of work Falk has done to be

in the public domain is perhaps best expressed by W. Duane Lockard,

Chairman of the Department of Politics at Princeton University:

"I believe it to be in the public ingerest for access

by scholars and journalists to confidential sources to

be protected to as wide a degree as is reasonably

possible. It is always better to have more rather than

less public knowledge about dissident groups— both to

let their ideas be presented through responsible sources

and to permit thoughtful analysis of the social and

political phenomina involved. Professor Falk's analysis

as a scholar and his journalistic presentation of evidence

and argumentation would seem to me to be outstanding

examples of the kind of work that deserves precisely the

kind of protection in question here. If his scholarly

and other professional activity serves the cause of a

democratic and open society, as I would insist it does,

then it deserves protection because it is quite literally

in the public interest." Lockard, Q, p. 59 .(Emphasis supplied)

17. E.g. William J. McLung, Managing Editor of the University of

California Press: "The strength of his scholarship and its value to our

society has been based in part, I believe, on his relationship of trust

with both opponents and defenders of American policies in Vietnam and

elsewhere." McLung, p, p. 57 . See also, Feiveson, H, quoted, supra, fn. 6

18. E.g. "Professor Falks contribution to our discussions and to our

further research./involving project participated in by scholars from

around the world/ are considered by the entire group to have been particularly;

significant and we are aware that some of his contributions have been based

on information regarding which he assured confidentiality of source."

Mendlovitz, K, p. 42 . "His contributions to at least three of these

conferences and seminars /Fund for New Priorities in America/were perhaps

the ipajor reason for the impact of our efforts in the areas of concern."

- 16 -

This assessment is shared, either explicitly or implicitly by all of

19

the affidavits before this Court.

b. A condition precedent to Movant's mere

appearance should be a shoving by the

government of compelling and overriding

national interest.

This contention, in its legal implications, is set forth

more fully, infra, pp 41-44. No such showing has yet been made in

the record before this Court, and that is the only kind of showing which

18. (cont.) Meyers, F, p. 34 . See also the account of Falk's unique

role in television coverage of the Paris negotiations, McGhee, Teicholz,

Cook, L,M,N, pp. 44-51 ; and his role in arranging contacts between

Congress and Paris negotiators, Falk, A, pp 12-13.

19. E.g., Mendlovita, K, at p.42 : "In my judgment there is an over

riding public interest in making certain that scholars and journalists

are able to carry out this type of investigation. Furthermore, any

procedures, such as an appearance before the grand jury, which jeopardizes

this confidentiality would seriously curtail this source of information....

Professor Falk's journalistic contributions on matters of world peace have

in my view been of immense importance to the American public over the past

four years."

Crown and Standard, O, at pp. 53-56: "We earnestly believe that

Professor Falk's very appearance before a Grand Jury pursuing this kind of

investigation will irreparably breach and damage associations and have a

chilling effect on his relationships with such sources of information to

the detriment of the public's right to know the truth about this crucial

issue affecting the very lives of Americans." (Emphasis supplied).

Thatcher, I, at p. '40 : "Such interference with the public's right

to know is tantamount, in the effect it would have, to overt official

censorship... If the people who provide such information on the understanding

that they will not be identified as its source see that there is no protec

tion against disclosure because Grand Jury investigations of this kind can

compel scholars and journalists to betray the trust placed in them, then it

is inevitable that these sources of information will dry up, and the public

- 17 -

19. (con't.)

will be deprived of the possibility of learning more of the truth than

official sources choose to reveal...and they would have no access to...

any insights or information other than what the public record disclosed."

(Emphasis supplied).

Meyers, F, at p. 34 : "Expertise is vital to the continuing

education process in a free society.... I believe that the expertise of

Professor Falk clearly requires the kind of source material which he must

receive on a confidential basis. If this opportunity is removed from him

and other experts and scholars the damage will be far greater than only to

their expertise." (Emphasis supplied). _ _

Barnet, B, at p. 29 : "To interfere with /Falk‘S important

public service by compelling him to appear before a Grand Jury investigating

matters within his professional competence as lawyer, scholar and journalist

would be a disservice to the public."

- 18 -

could force Falk to testify beyond the confines of the kind of protective

order to which he is entitled. Furthermore, Falk states in his affidavit

that there is absolutely nothing as to whii h he could testify which would

not be proscribed by such an order. See Falk, A, p. 21 . Thus, on the

record as it now stands, this Court, by compelling mere appearance, would

essentially be compelling an act useless to the grand jury and damaging

to Falk. The damage,in this context, is not so much the danger of revealing

particular confidences before the grand jury which relate to the Pentagon

Papers, as a protective order would proscribe that. The damage is the

obvious and inevitable certainty, already spelled out in our summation of

the record, that sources of information concerning the war, particularly,

and foreign policy generally, would be inhibited for fear of an attempt to

compel disclosure before some future tribunal in some context as yet unknown.

We would ask this Court to bear in mind that fears and inhibitions of this

sort, particularly on the part of laymen and foreign sources (with whom

Falk deals regularly) do not ebb and flow as a function of the technical

distinction between "mere appearance" and "actual testimony". That the

government may seek to compel disclosures, not that such disclosures will

actually occur, sets these chilling fears in motion.

- 19 -

IV.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE PROFESSIONAL AND PUBLIC-EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES

MOVANT SEEKS TO PRESERVE ARE PROTECTED BY THE FIRST

AMENDMENT AGAINST GOVERNMENTAL INTRUSION

The issue before this Court, quite apart from that of the

proper scope of a protective order, is whether any privilege at all

20

attaches to movant's professional activities. This question, to the

extent that it may relate to movant's non-journalistic activities,is

one of first impression. The related question, assuming a privilege,

of whether the government must, in advance of testimony, show a compelling

need for mere appearance before the grand jury was decided affirmatively

in Caldwell v. United States, 434 F.2d 1081 (9th Cir., 1970), cert granted

21

91 S. Ct. 1616(1971).

20. Cf. Caldwell v. United States 434, F.2d 1081, 1083 (9th Cir. 1970),

cert, granted 91 S. Ct. 1616 (1971): "...before we can decide whether the

First Amendment requires more than a protective order delimiting the scope

of interrogation, we must first decide whether it requires any privilege

at all."

21. This is the clear holding of Caldwell, 434 F.2d at 1089. Judge Jameson's

concurring opinion agrees with Judge Merrill on the proposition that where a

privilege attaches, the government could properly be required to show

compelling need even prior to the issuance of a subpoena. Caldwell, supra

at p. 1092. Clearly the Caldwell inspired Department of Justice guidelines

for subpoenas to the news media envisage this, fn. 3, at 1091.

- 19A -

A. Movant's Journalistic Activities, Because They Are

Primarily Concerned With The Subject Matter Of The

Pentagon Papers, Fall Within The Scope Of Caldwell v,

United States.

The record before the Court is clear and uncontradicted for

the proposition that Richard Falk's journalistic activities related to

the War entitle him to the kind of protection afforded Earl Caldwell.

See pp. 9-10 , supra. Nor should Falk suffer because his activities have

encompassed so much more than journalism, strictly defined . Indeed

precisely the opposite, for of all his activities, those related to

journalism have directly reached a more diverse kind of audience than his

scholarly and consultative pursuits, and,in fact, were intended to secure

this end. Researchers and academicians have assumed in our society many

of the functions formerly reserved to journalists as social and political

22

commentators. And where they utilize the mass media to impart their

commentary and expertise to the public they act within limits long protected

by the First Amendment. Caldwell, supra, at 1084. The very subject of

this grand jury investigation has been afforded similar sweeping protection.

New York Times v. United States, 91 S. Ct. 2140(1971). To argue, as the

22. Cf. Horowitz and Rainwater, "Sociological Snoopers and Journalistc

Moralizers," 7 Transaction 4,5 (May, 1970): "The intertwinings of journal

istic and sociological expertise are complex indeed and have been from the

early days of empirical American sociology." And see Steel, J, infra, at

fn. 10.

- 20 -

government must in this case, that national interest cannot prevent the

American public's access to this material but that that same national

interest somehow proscribes Falk's right to professionally assess its

significance seems disengen ous.

B. Notwithstanding The Applicable Scope Of The Journalist

Privilege, Movant's Activities As A Professional Scholar

And Author Are Themselves Cognizable Under The First____

Amendment, And, As Such, Are Entitled To The Parameters

Of Protection Established By Caldwell.

The sum total of Movant's scholarly activities has been a

virtually unending stream of books, articles, monographs and lectures

relating to American foreign policy in the context of the Vietnam War.

This work product is impressively recounted in the Falk affidavit, as

well as the crucial and unique role which confidence and trust have played

in this effort at "getting at the real facts" (Falk, A, 3) and "the best

available evidence" (Falk, A. 17). The primary goal of these efforts

has been to publish this material as widely as possible and in such a way

as to bring insightful and comprehensive information to professional

colleagues, the Congress, and the American public. On the record before

this Court there is no question but that, in his field, Richard Falk's

writings and commentary are authoritative, and that the subject matter of

the Pentagon Papers is vitally and intimately related to his work.

It is by now a commonplace that informed scholarship and the

processes of its distribution are protected by the First Amendment:

"...the State may not, consistently with the

spirit of the First Amendment contract the

spectrum of available knowledge. The right

- 21 -

of freedom of speech and press included not only

the right to utter or to print, but the right to

distribute, the right to receive, the right to

read...and freedom of inquiry, freedom of thought,

and freedom to teach..-- indeed the freedom of the

entire university community...Without these periph^^al

rights, the specific rights would be less secure."

(Emphasis supplied).

Each of the steps in this progression from information collection

to publication and dissemination has been protected by the Court.

The freedom to publish and circulate news has long been established.

24

indeed, in the very context of Richard Falk's concern. New York Times v.

25United States, supra. The freedom to write and the freedom of the

26

public to receive information have more recently been perceived as

distinct rights. Moreover, the information gathering functions of

27

investigators are clearly protected by the First Amendment, and are the

23. Griswold v. Connecticut, supra, 381 U.S. at 482-3. Citations omitted.

24. See, e.g.. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 713(1931); Lovell v. Griffin,

303 U.S. 44(1937); Winters v. United States, 333 U.S. 507(1943);

Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60(1960).

25. See e.g.. New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254(1964);

Beckley Newspapers Corp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S. 81(1967).

26. See, e.g., Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 U.S. 141(1943); Lamont v.

Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301(1965); Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S.

557(1969) .

27. Associated Press v. KVOS, 80 F.2d 575, 581(9th Cir. 1935), rev'd on

other grounds, 229 U.S. 269(1936). See also Providence Journal Co. v.

McCoy, 94 F.Supp 186, 195-196(D.R.I., 1950) aff'd on other grounds

190 F.2d 760(lst Cir. 1951).

- 22 -

factual and constitutional precondition of the ability to publish and

circulate.

All of these rights take on added import when interpreted

28

in light of the particular needs of the academic community. Mr. Justice

Frankfurter, in language so apposite to Falk's professional roles and

the record before this Court that it bears quotation at length, clearly

recognized this;

"Progress in the national sciences is not remotely

confined to findings made in the laboratory. Insights

into the mysteries of nature are b o m of hypothesis and

speculation. The more so is this true in the pursuit of

understanding in the groping endeavors of what are called

the social sciences, the concern of which is man and

society. The problems that are the respective preoccupa

tions of anthropology, economics, law, psychology,

sociology and related areas of scholarship are merely

departmentalized dealing, by way of manageable division

of analysis, with interpenetrating aspects of holistic

perplexities. For society's good— if understanding be an

essential need of society— inquiries into these problems

speculations about them, must be left as unfettered as

possible. Political power must abstain from intrusion into

this activity of freedom, pursued in the interest of wise

government and the people's well-being, except for reasons

that are exigent and obviously compelling.

These pages need not be burdened with proof, based on

the testimony of a cloud of impressive witnesses, of the

dependence of a free society on free universities. This

means the exclusion of governmental intervention on the

intellectual life of a university. It matters little whether

28. The Supreme Court has recognized these needs as "almost self-

evident". Sweezv V. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 250(1957): "Teachers and

students must always remain free to inquire to study and to evalute, to

gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise our civilization will

stagnate and die."

- 23 -

such intervention occurs avowedly or through action

that inevitably tends to check the ardor and fear

lessness of scholars, qualities at once so fragile

and so indispensable for fruitful academic labor.

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 261-262(1957)

(Frankfurter, J, concurring).

This language, flowing as it did from a case involving refusal of a witness

(legislative) to give compelled testimony, is all the more relevent.

In Sweezy, as here, the government offered no evidence that

29

Professor Sweezy had himself, violated the law, but rather justified

30

compulsion with the assertion that he might lead them to others that had.

It is clear that the First Amendment "rests on the assumption

that the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and

31

antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public." This is

particularly so when such information is vitally relevent to issues of

national concern, posed, as with the Vietnam War, in times of

29. 354 U.S. at 261.

30. This Court has expressed an inclination to look to In Re Murtha, N.J.

Super. Ct., App Div. 7/6/71, for guidance on this question. Murtha is

discussed, infra, p. 39, but it is well to note here that the existence of a

First Amendment privilege was found lacking in that case. To the extent that

Falk protected by such a privilege, as we believe is clearly demonstrated,

Murtha is not authority for compelling his testimony in the absence of a

particularized governmental need therefor.

31. Associated Press v. United States, 325 U.S. 1, 20(1945).

Cf. Keyishian v. Bd. of Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 603(1967): "Our

Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of

transcendent value to all of us....That freedom is therefore a special con

cern of the First Amendment ....The classroom is peculiarly the "market place

of ideas". The Nation's future depends upon leaders trained through wide

exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth..."

(citations omitted).

- 24 -

32

crisis. That this work ought to be encouraged in the university,

and that it ought not be interfered with by governmental intrusion,

is at the heart of the evolution of the legal concept of academic

33

freedom. Indeed, because of its devotion to scholarship and academic

inquiry, the university conforms to the "marketplace of ideas" concept

even more fully than does the public forum. For this reason the danger

of infringement is particularly circumscribed by the First Amendment,

Sweezy, supra.

As is the case with all constitutional protections,this

recognition of academic freedom has incorporated within it a judicial

evaluation that the activities to be protected are so valuable to society

that a compelling and overriding interest is the condition precedent for

governmental intrusion upon them. Certain observations about the value

of academic inquiry, of which Falk's activities are but an example, may

be useful to this Court. First, empirical academic research, the

gathering of reliable and relevant infomation, is crucial to its success

Second, issues which are created, as here, when the government seeks to

invade the confidentiality necessary to academic inquiry.cafinot be adequately

34

32. As the court.in Caldwell points out, the need "takes on special

urgency in times of widespread protest and dissent. In such times the

First Amendment protections exist to maintain communication with dissenting

groups and to provide the public with a wide range of information about

the nature of protest and heterodoxy." Caldwell, supra, at 1084-5.

See also Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 102(1940); Associated Press v.

United States, supra, fn. 31.; Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64(1964).

- 25

(Footnotes continued)

33. See, generally, "Developments in the Law of Academic Freedom,"

81 Har\t> L. Rev. 1045, 1048(1968), and sources there cited. This concept

of academic freedom is reflected not only in recognition of the need for

such freedom, but also in certain institutional arrangements designed to

protect it. See, e.g., C. Byse and L. Joughin, Tenure in American Higher

Education (1959).

34. Certainly Falk's affidavit is replete with references to how crucial

it is to him, particularly in the context of the Pentagon Papers. E.g,

Falk, A, 17.

Extensive literature supports the societal value of empirical

research in other contexts. For instance, a National Science Foundation

commission has noted its relevence to education, engineering, journalism

law, labor relations, medicine, and public health, mental health and

social work. Brim(Chairman), Knowledge Into Action; Improving the

Nation's Use of the Social Sciences (1969). U.S. Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, Toward a Social Report (1969); Staff of House of

Representatives Research and Technical Programs Sub. Comm. On Government

Operations, 90th Cong., 1st Sess., "The Use of Social Research in Federal

Domestic Programs," 4 Parts (Comm. Print 1967); Orleans, "The Political

Uses of Social Research," 314 The Annals 28(1971); Lyons, "The President

and his Experts," 394 The Annals 36(1971); Beckman, "Congressional Informa

tion Processes for National Policy," 394 The Annals 84(1971); Reicken,

"The Federal Government and Social Science Policy," 394 The Annals 100(1971);

W. Bateman, An Experimental Approach to Program Analysis; Step Child in

The Social Sciences? (1969); Holt, "A System of Information Centers for

Research and Decision Making", 60 Am. Economic Rev. 149(1970).

For these and other sources counsel to Richard Falk are indebted

to Paul Nejelski, Esq., and Lindsey Miller Lerman, whose soon to be published

monograph entitled "Protection of Confidential Research Data" has generously

been made available to us.

- 26 -

framed in terms of the suppression of truth versus the professional

inconvenience which might result. When requests are made for confidential

information, two forms of truth are competing— judicial testimony versus

society's interest in access to competent and accurate information.

The evaluation of a particular request for confidential information must

thus recognize that but for the confidentiality which attaches to a scholar's

35

inquiries, society's interest would not be served. The government's

ability to close off a particular kind of inquiry by forcing such disclosure

is clearly an intimidating power, made even more dangerous by the fact that

it is only likely to be used, or for that matter necessary, when dealing

with critics or potential critics of government policy. Indeed the

36

particular stiuation of Richard Falk appears an apt lesson in this regard.

35. The peculiar irony of this is that but for this confidentiality, the

interest of this grand jury, whatever it may be,likewise cannot be served.

By compelling the disclosure of such confidences, and thus insuring that they

will not be made in the future, a grand jury would in effect choke off its

own ability to ascertain truth where, not as here, there really a compel

ling, overriding, and urgent need. See Caldwell, supra, at 1086, fn. 5 and

accompanying text.

The chilling effect which would be caused by the vulnerability of

research findings is at least partially aggravated by a growing suspicion

between the research community, especially academia, and government.

University criticism of the Vietnam War has emphasized that academia— like

the news media— represents an independent power which cannot be readily

manipulated by the government. In addition, the rejection or, at best,

indifference, with which the reports of Presidential Commissions have been

received, has discouraged researchers who have worked on or identified with

these projects. To the extent that compelled grand jury disclosure of

research confidences acts as a further disincentive, it must be avoided.

See Green, "The Obligations of American Social Scientists", 394 The Annals

13, 25(1971). See also Caldwell, supra, at 1086.

- 27 -

Footnotes continued

36. Cf., Grosjean v. American Press Co.. 297 U.S. 233, 250(1936);

"...since informed public opinion is the most potent of all restraints

upon misgovernment, the suppression or abridgement of the publicity

afforded by a free press cannot be regarded otherwise than with grave

concern."

- 28 -

Movant's Professional Activities Are Protected Against This

Grand Jury's Intrusion Unless And Until The Government______

Demonstrates National Interest So Compelling, Overriding, And

Unique to Movant, That It Outweighs The Public Worth Of His

Own and Similar Protected Pursuits.

The issue before this Court requires a judicial evaluation of

the strength of the government's objectives and the appropriateness of

37

its methods. The Court is thus faced with the task of articulating

justiciable standards with which to measure the amount of protection

37 A

Falk ought to be accorded. It is clear, however, that once a First

Amendment privilege is established, the parameters of protection set forth

in Caldwell v. United States, supra, ought expressly to be applicable.

This is true regardless of whether Falk's First Amendment privilege

attaches due to his journalistic pursuits, on the one hand, or his

activities as a scholar and author, on the other. In fact, this combination

of roles, fully documented in the record, makes his side of this balance

weigh even more.

The Court in Caldwell reached its result with full recognition

of the broad and unfettered scope of inquiry which grand juries have

traditionally exercised, 434 F.2d at 1085, and Professor Falk likewise

expresses such respect, Falk, A, 21. Caldwell also found guidance in the

37. Where, as here, the alleged abridgement of First Amendment interests

occurs as a by-product of otherwise permissible governmental action not

directed at the regulation of speech or press, "resolution of the issue always

involves a balancing by the courts of the competing private and public

interests at stake in the particular circumstances shown." Barenblatt v. U.S.

- 29 -

Footnotes continued

37. (cont.) , 360 U.S. 109, 126(1959); see, e.g., Konigsberg v. State

Bar of Cal., 366 U.S. 50-57(1961); Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516,(1960)

NAACP V. Alabama ex rel. Pattersen, 357 U.S. 449, 460-467, (1958);

Kalven, "The New York Times Case: A Note on 'The Central Meaning of the

First Amendment.' " 1964, Sup. St. Rev. 191, 214-16(1964).

37 . As set forth infra, p. 38 , this balancing requires a showing by the

Government that it has no other sources of information which do not involve

an "equal degree of incursion upon First Amendment freedoms."

In assessing what "degree of incursion" is here present, the Court

must look not only to the general nature of the First Amendment freedom

asserted, but also to its relative strenth in the particular case. Thus,

the Court in Caldwell found that because of Caldwell's uniqueness, he was

entitled to a showing of "compelling and overriding national interest."

Falk's uniqueness to his own profession is at least equal to, if not

stronger than, Caldwell's; and, correspondingly, the same compelling urgency

ought to be shown by the Government in order to force his appearance.

Another way of expressing this is to say that the record before this Court

is at least as narrow as that before the Caldwell court; and the narrowness

of the record is the strongest reason for affording the protection sought.

See Caldwell, gupra, at 1090, discussed infra, p. 44

- 30 -

Supreme Court decisions regarding conflicts between First Amendment

interests and legislative investigatory needs, 434 F.2d at 1085-6, and

found, on a record notably similar to the record before this Court, that

the government's burden in the balancing process simply had not been met.

In the absence of compelling and overriding need, then, the government

cannot be permitted the power to "appropriate" protected "investigative

efforts" to its own behalf— to convert a witness, after the fact, "into

38

an investigative agent". 434 F.2d at 1086.

In order to demonstrate such need the government must, at the

least, establish the following:

(1) The information sought must be demonstrably relevant

to a clearly defined, legitimate subject of governmental inquiry. The

reason for demanding clear definition of the subject of the investigation

is plain. Like the requirement that legislation which may trench on

39

First Amendment interests meet "strict" standards of specificity, insis

tence on strict definition of the scope of an investigation assures that

38. This Court might bear in mind that the particular problem of protecting

academic and scholarly investigative confidences has already been recognized

and planned for in other contexts. One notable example are the guidelines

issued by the American Council on Education for their ^tudy of campus unrest;

"5. /the above named emplyees of the projecjt/ will explicitly

undertake to protect all confidential information, whether

recorded or not, that i.s revealed to them. They will specifically

agree to refuse to divulge confidential information to any______

person or group, including investigative agencies, committees,

and courts of law, even if they or their records should be_______

subpoenaed'̂

- 31 -

Footnotes continued.

38. (cont.)

"6.....we advise and counsel all researchers in

this study /presumably not including those named in

paragraph 5, supra/ to refuse to release or provide

any confidential information, even if directed to do

so by a subpoena or other court process from a legis

lative body or court of law. We will support with all

all legal means any such refusal."

Emphasis supplied. Advisory Committee A.C.E. Study on Campus Unrest,

"Statement on Confidentiality, Use of Results, and Independence," 165

Science 158, 159(July 11, 1969).

These guidelines are cited advisedly, as the investigation of campus

unrest would be quite likely to expose evidence of crimes which the

government would obviously be entitled to prosecute.

39. E.g. Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147, 151(1959); Cramp v. Board of

Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278, 287— ^288(1961); NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415, 432-433(1963); Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195, 200(1966).

- 32 -

the governmental body whose processes may intrude upon the First

Amendment has focused both upon its purposes and upon the question of

whether those purposes require the intrusion. See Mr. Justice Harlan,

concurring, in Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157, 203(1961). The

requirement is a safeguard against overbroad and formless investigations

which — like overbroad and formless laws — "lend themselves too readily

to the denial of /First Amendment_/ . . . rights." Dombrowski v. Pfister,

380 U.S. 479, 486(1965). See particularly, Liveright v. Joint Committee,

279 F. Supp. 205, 215, 217 (M.D. Tenn. 1968). Finally, the requirement of

strict definition of the subject under investigation is indispensable to

enable first the subpoenaed witness and his counsel, and later the courts

themselves, to determine the point of proper balance between investigative

need and the privacy protected by the First Amendment. For all these

reasons, indefiniteness in the scope of governmental inquiry has consistently

been regarded as fatal to investigations in the First Amendment area.

Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178(1957); Sweezy v. New Hampsire, supra

Scull V. Virginia ex rel. Committee on Law Reform and Racial Activities,

359 U.S. 344(1959); Liveright v. Joint Committee, supra.

And, once the subject of an investigation has been adequately

defined, the use of compulsory process is required to be confined to matters

strictly relevant to that subject. Ordinarily, of course, the command that

grand jury subpoenas seek only evidence relevant to the jury's inquiry is

administered with considerable elasticity. E.g., In Re Grand Jury Subpoena

- 33 -

Duces Tecum, 203 F. Supp. 575, 579(S.D.N.Y. 1961). But that degree of

tolerance may not be indulged whereinquiry touches First Amendment interests,

for in these latter areas compulsory disclosure is forbidden unless it is

"demonstrated to bear a crucial relation to a proper governmental interest

or to be essential to the fulfillment of a proper governmental purpose."

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, supra, 372 U.S., at

549. See DeGregory v. Attorney General of New Hampshire, 383 U.S. 825(1956)

(2) It must affirmatively appear that the inquiry is likely to

turn up material information, that is; (a) that there is some factual basis

for pursuing the investigation, and (b) that there is reasonable ground to

conclude that the particular witness subpoenaed has information material

to it■ In the First Amendment area, even relevant inquiries may not be pur

sued without some solid basis for belief that they will be productive. For

example, Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F.2d 597, 606 (4th Cir. 1963), condemned

a legislative investigation which purported to inquire into certain criminal

activities but also resulted in the disclosure of constitutionally protected

associations, saying that courts "can and should protect the activities of

the plaintiffs . . . in maintaining the privacy of their First Amendment

activities against irreparable injury unless and until there is a reasonably

demonstrated factual basis for assuming that they are guilty of the offenses

which the Committee is investigating."

- 34 -

"of course, a legislative investigation —

as any investigation — must proceed 'step by

step', . . . , but step by step or in totality,

an adequate foundation for inquiry must be laid

before proceeding in such a manner as will substantially

intrude upon and sev%ely curtain or inhibit constitu

tionally protected activities or seriously interfere

with similarly protected associational rights."

(Gibson V. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee,

supra, 372 U.S., at 557.)

(3) The information sought must be unobtainable by means

less destructive of First Amendment freedoms. This requirement derives

from the pervasive First Amendment principle of the "narrowest effective

means," recognized in cases of compulsory disclosure of protected associa

tions, e.g., Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 488(1960); Louisiana ex rel.

Gremillion v. NAACP, 366 U.S. 293, 296-297(1961), as in others, e.g.,

Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U.S. 11, 18(1966). Simply stated, the principle

is:

"that a governmental purpose to control or prevent

activities constitutionally subject to state regula

tions may not be achieved by means which sweep un-

nec^sarily broadly and thereby invade the area of pro

tected freedoms. .../T /he power to regulate must be

so exercised as not, in attaining a permissible_end^ unduly

to infringe the protected freedom. ... '. . ./E/ven though

the governmental purpose be legitimate and substantial, that

purpose cannot be pursued by means that broadly stifle

fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more

narrowly achieved.' " (NAACP v. Alababa ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S,

288, 307-308(1964).)

- 35 -

As applied to this grand jury investigation, this principle leads plainly

to the conclusion that the jury may not compel Falk's testimony, intruding

into and threatening destruction of his confidential relationships, if

it can find out what it wants to know from other sources that do not

40

implicate First Amendment concerns.

40. Compare In Re Murtha, 40 USLW 2052, discussed infra, p. 39

We think that Garland v. Torre, 259 F.2d 545 (2d Cir. 1958), recognizes

this point. The case arose out of a defamation action brought by Judy

Garland against the Columbia Broadcasting System, predicated on the

complaint that CBS had made libelous statements against Miss Garland and

affirmatively induced their publication in newspapers and elsewhere. A

critical instance of the alleged defamation was a newspaper column by

Marie Torre containing statements about Miss Garland attributed to a CBS

"network executive." In pretrial proceedings, the two CBS executives whom

Miss Garland had named in her deposition as the likely sources of the Torre

story were deposed and denied all knowledge of it. Counsel for Garland

then deposed Marie Torre and inquired concerning her source; Miss Torre

refused to answer, clai'ming a First Amendment privilege; and she was held

in contempt.

The Second Circuit (per Judge Stewart, now Mr. Justice Stewart),

affirmed the contempt commitment, but only after accepting "at the outset

the hypothesis that compulsory disclosure of a journalist's confidential

sources of information may entail an abridgment of press freedom by imposing

some limitation upon the availability of news." 259 F.2d, at 548. "What

must be determined is whether the interest to be served by compelling the

testimony of the witness in the present case justifies some impairment of

this First Amendment freedom."(Ibid) The court held that it did because the

Torre testimony "went to the heart of the plaintiff's claim" (I^., at 550)

in a case that was being prepared for trial. Torre was plainly the only

available source of the information sought from her, and accordingly the

Second Circuit emphasized "that we are not dealing. . . with a case where

the identity of the news source is of doubtful relevance or materiality"

(Id., at 549-550). The force of the Garland court's reservation is the

more apparent with regard to grand jury proceedings, for grand juries inquire

only to determine probable cause; and they therefore have no compelling

need for cumulative evidence — evidence from more than one source — which,

for a trial jury, might spell the difference of persuasion.

- 36 -

40.(cont.)

Finally, Garland v. Torre appears to recognize — as we think

it must consistently with Shelton v. Tucker, supra; Gibson v. Florida

Legislative Investigation Committee, supra; and DeGregory v. Attorney

General of New Hampshire, supra — that governmental attempts to compel

disclosure of confidential associations may sometimes be forbidden by the

First Amendment even though the protected evidence is sought under pro

cedures and circumstances that meet the requirements we have

described in paragraphs (1), (2), and (3), in text supra. This is implicit

in the Second Circuit's approach of particularistic "balancing" of First

Ttoiendment freedoms against the justifications for compelled disclosure,

and in the court's recognition that Garland did not involve "the use of

judicial process to force a wholesale disclosure of a newspaper's confi

dential sources of news" (259 F.2d., at 549). The proviso implies, at the

least, a prohibition of compelling Falk to make disclosures whose broadly

destructive effect upon First Amendment freedoms palpably outweighs the

value of the uses to which a government investigation body may put them.

Cf. United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Ass'n, 389 U.S. 217(1967).

As to this latter point, see also fn. 37A, supra.

- 37 -

These established principles dictate the test that we set

forth in the motion to quash originally filed with this Court, namely,

that the government must show:

(1) Reasonable grounds to believe that Richard Falk has

information, which is

(2) Specifically relevant to an identified episode that this

Grand Jury has some factual basis for investigating as a possible violation

of designated statutes within its jurisdiction; and

(3) That the government has no alternative sources of the40A

same or equivalent information whose use would not entail an equal degree

of incursion upon First Amendment freedoms.

Is there, then, a sufficient governmental showing of compelling

and overriding need to force Richard Falk's appearance before the grand

41

jury? We have only a government representation that the grand jury is

investigating the alleged commission of a variety of statutory offenses all

of which presvimably relate to the Pentagon Papers. This broad assertion

plainly does not meet the test set out above.

First, let it be noted that the government is seeking to compel

Falk's appearance for the apparent purpose of testifying about the distri

bution and publication of materials whose distribution and publication may

41. Made, it should be noted, not in this case but on August 19, in the

matter of Stephen Popkin, who was later excused by the Government.

40A. See, infra, fn. 37A

- 38 -

not, consistent with the First Amencinent, be suppressed. New York Times v.

United States, supra. Nor has there been any demonstration that there has

been committed any crime other than that alleged to Daniel Ellsberg, or

that, assuming there has, Falk has some direct and immediate knowledge of

it, or that, assuming he does, such information would not be forthcoming

from someone else. In Re Murtha, N.J. Super. Ct., App Div. 7/6/71, in

which this Court has expressed interest, is instructive in these regards:

A murder had clearly occurred. Sister Murtha had voluntarily admitted to

the police that a direct, unambiguous admission had been made to her, and

42

she was the only person to whom the information had been given. And,

apart from all of this and most important of all, she had demonstrated no

First Amendment or other testimonal privilege which might protect these

43

revelations.

42. In Re Murtha. in this regard, is similar to Garland v. Torre, fn. 40

supra.

Worth mentioning in this context is the fact that, according to news

paper accounts, zerox copies of all or a portion of the Pentagon Papers