Daniel v. Paul Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Daniel v. Paul Brief for Petitioners, 1969. f3c0f8f1-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/98a18a20-29dd-4671-82df-d0667a5d3542/daniel-v-paul-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Copied!

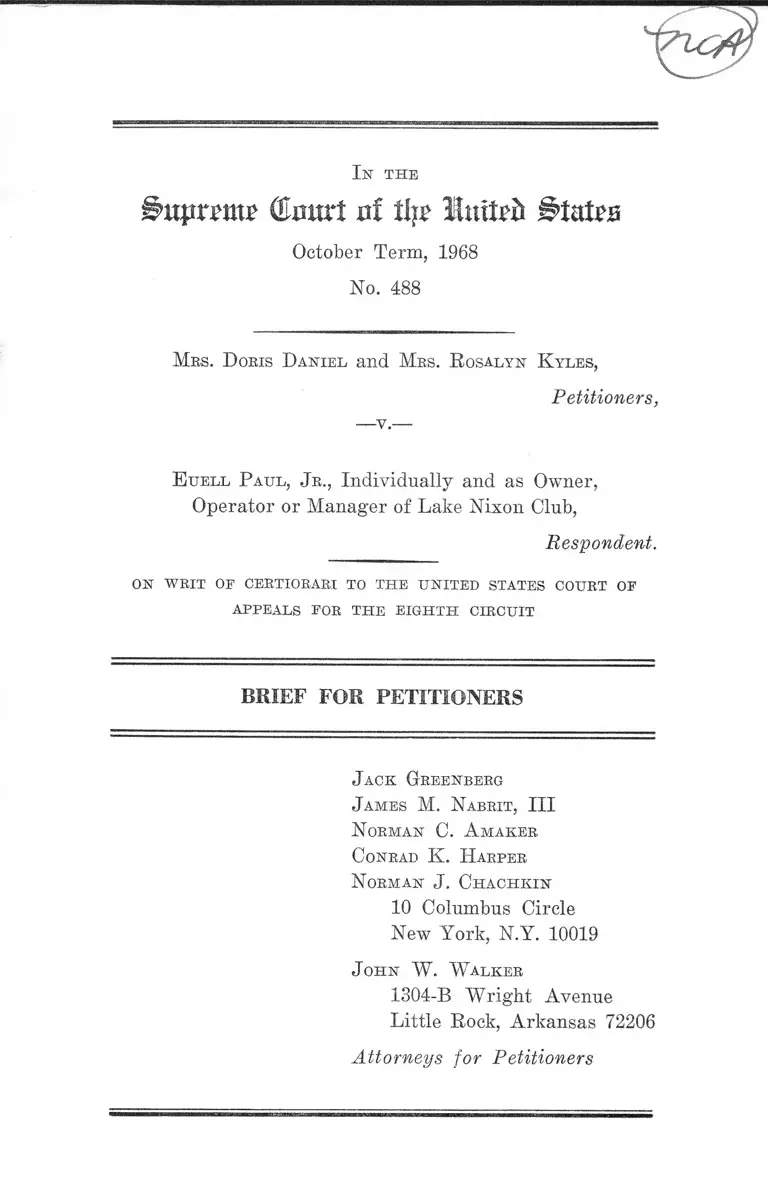

I n t h e

OJimrt at tip United Ĵ tatTB

October Term, 1968

No. 488

M rs. D oris D an iel and M rs. R osalyn K yles,

Petitioners,

E u ell P au l , Jr., Individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES COURT OF

APPE A LS FOR T H E E IG H T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A m aker

C onrad K. H arper

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ............................................. 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented....................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ....... 3

Statement ....... 5

Summary of Argum ent...................................................... 7

A r g u m e n t 1—

I. Lake Nixon Club, a Place of Public Accommo

dation, Which. Offers to Serve Interstate Trav

elers and Provides Food, Facilities for Enter

tainment, and Other Products Which Have

Moved in Commerce, Is Barred From Excluding

Petitioners by Title II of the 1964 Civil Bights

Act .............................................................................. 9

A. Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act Applies

to the Whole of Lake Nixon Because of Its

Lunch Counter’s Operations............................. 9

B. Like Nixon Is a Place of Entertainment As

Defined by Title II of the 1964 Civil Bights

Act ......................... —........................................... 14

II. The Equal Bight to Make and Enforce Contracts

and to Have an Interest in Property, Guaran

teed by 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1982, Includes the

Right of Negroes to Have Access to a Place of

Public Amusement .................................................. 18

Conclusion ....................................................................... 21

11

T able op A uthorities

Cases: page

Civil Eights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ......... ............... . 20

Codogan v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M.D. Fla. 1967) .... 12

Coger v. The North West Union Packet Co., 37 Iowa

145 (1873) .......... 20

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967) .... 19

Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (EJD.

Va. 1966) .......................................................................... 13

Fazzio Eeal Estate Co. v. Adams, 396 F.2d 146 (5th

Cir. 1968) ...........................................................10,12,13,19

Gregory v. Meyer, 376 F.2d 509 (5th Cir. 1967) ........... 11

Griffin v. Southland Pacing Corp., 236 Ark. 872, 370

S.W.2d 429 (1963) .......................................................... 18

Hamm v. Kock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964) .....................11,13

Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .........18,19, 20, 21

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) ................ 12

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 394 F.2d 342

(5th Cir. en banc, 1968) ...................................11,14,16,17

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 256 F. Supp.

941 (D.S.C. 1966), rev’d, 377 F.2d 433 (4th Cir.

1967), mod. and aff’d on oth. gds., 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ........ 19

Scott v. Young, 12 Race Eel. L. Rep. 428 (E.D. Ya.

1966) .................................................................................. 13

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 392 U.S. 657

(1968) 2 0

I ll

Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 37 U.S.L.W. 4068 (U.S.

PAGE

Jan. 13, 1969) ................................................................ 19,20

Vallee v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697 (3rd Cir. 1949) ........... 18

Wooten v. Moore, 400 F.2d 239 (4th Cir. 1968) ........... 10

Constitutional Provisions:

Commerce Clause, Art. 1, §8, cl. 3

Thirteenth Amendment ................

Fourteenth Amendment ................

Statutes-.

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) ................................................ 2

48 U. S. C. §1981 ...............................2, 3, 5, 8,18,19, 20

42 IT. S. C. §1982 .................................. 2, 3,8,18,19, 20

42 U. S. C. §2000a (§201) ......... 2,5,8,9,12,13,14,19

42 U. S. C. §2000a(b) (§201(b)) ............. 3,8,9,10,12

42 U. S. C. §2000a(c) (§201(c)) ............. 4,8,9,10,11,

12,16,17

42 U. S. C. §2000a(e) (§201(e)) ........................... 11

42 U. S. C. §§3601-3631 ............................................. 18

3.5

3, 20

3.5

IV

Miscellaneous:

PAGE

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 43, 322, 475, 541,

599 ; Appendix 69, 183, 936 ............ ..................... 20

109 Cong. Eec. 12276 (1963) ................................ 15,16

110 Cong. Eee. 6557 (1964) ............... ..................... 17

110 Cong. Eee. 7383 (1964) ........... . ...................... 15

110 Cong. Eee. 7402 (1964) ............... ...................... 16

110 Cong. Eec. 13915 (1964) ............. .................. . 17

110 Cong. Eec. 13921 (1964) .................................. 17

110 Cong. Eec. 13924 (1964) ............................. . 17

Flack, H., The Adoption of the

Amendment (1908) ...........................

Fourteenth

..................... 20

Hearing's on Miscellaneous Proposals Eegarding

Civil Eights Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the

House Committee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. ser. 4, pt. 2 (1963) ................................ 15

Hearings on H.E. 7152 Before the House Commit

tee on the Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. ser.

4, pt. 4 (1963) ......................................................... 15

H. E. Eep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) .... 13

S. Eep. No. 872 on S. 1732, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess.

(1964) 17

I n t h e

dmtrt nf tty? Init^ States

October Term, 1968

No. 488

Mrs. D oris D an iel and Mss. R osalyn K yles,

-v .—

Petitioners,

E u ell P au l , J r ., Individually and as Owner,

Operator or Manager of Lake Nixon Club,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OE CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR T H E E IG H T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Citations to Opinions Below

The February 1, 1967 memorandum opinion of the Dis

trict Court, reprinted in the Appendix at pp. 47-62, is re

ported at 263 F. Supp. 412. The May 3, 1968 opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit, reprinted in the Appendix at pp. 64-82, is reported

at 395 F,2d 118. The dissenting opinion of Judge Heaney,

reprinted in the Appendix at pp. 82-90, is reported at 395

F.2d 127.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit was rendered May 3, 1968. A peti

tion for a rehearing en banc was denied on June 10, 1968.

A petition for writ of certiorari was filed September 7,

1968 and granted December 9, 1968 (A. 105). The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C.

§1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Lake Nixon Club is a privately owned and operated

recreational area open to the white public in general. Lake

Nixon has facilities for swimming, boating, picnicking,

sunbathing, and miniature golf. On the premises is a snack

bar principally engaged in selling food for consunrption on

the premises which offers to serve interstate travelers

and which serves food a substantial portion of which has

moved in commerce.

a) Is the snack bar a covered establishment within the

contemplation of Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

and if so, does this bring the entire recreational area within

the coverage of Title II?

b) Is the Lake Nixon Club a place of entertainment

within the scope of Title II?

2. Petitioners are denied admission to Lake Nixon Club

solely because they are Negroes. Have petitioners been

denied the same right to make and enforce contracts and

have an interest in property, as is enjoyed by white citi

zens, in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment and an

Act of Congress, 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982?

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Commerce Clause, Art. 1, §8, cl. 3,

and the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments of the

Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the following United States

statutes:

42 U. S. C. §1981:

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States

shall have the same right in every State and Territory to

make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evi

dence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and

proceedings for the security of persons and property as

is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions

of every kind, and to no other.

42 U.S. C. §1982:

All citizens of the United States shall have the same

right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white

citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and

convey real and personal property.

42 U. S. C. §2000a(b):

Each of the following establishments which serves the

public is a place of public accommodation within the mean

ing of this subchapter if its operations affect commerce,

or if discrimination or segregation by it is supported by

State action:

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch counter,

soda fountain, or other facility principally engaged in sell

4

ing food for consumption on the premises, including, but

not limited to, any such facility located on the premises

of any retail establishment; or any gasoline station;

(3) any motion picture house, theater, concert hall, sports

arena, stadium or other place of exhibition or entertain

ment; and

(4) any establishment (A ) (i) which is physically located

within the premises of any establishment otherwise covered

by this subsection, or (ii) within the premises of which is

physically located any such covered establishment, and

(B) which holds itself out as serving patrons of such

covered establishment.

42 U .S .C . §2000a(c):

The operations of an establishment affect commerce

within the meaning of this subchapter if . . . (2) in the

case of an establishment described in paragraph (2) of

subsection (b) of this section, it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers or a substantial portion of the food

which it serves, or gasoline or other products which it

sells, has moved in commerce; (3) in the case of an estab

lishment described in paragraph (3) of subsection (b) of

this section, it customarily presents, films, performances,

athletic teams, exhibitions, or other sources of entertain

ment which move in commerce; and (4) in the case of an

establishment described in paragraph (4) of subsection (b)

of this section, it is physically located within the premises

of, or there is physically located within its premises, an

establishment the operations of which affect commerce

within the meaning of this subsection. For purposes of

this section, “ commerce” means travel, trade, traffic, com

merce, transportation, or communication among the sev

eral States, or between the District of Columbia and any

5

State, or between any foreign country or any territory or

possession and any State or the District of Columbia, or

between points in the same State but through any other

State or the District of Columbia or a foreign country.

Statement

On July 18, 1966, petitioners, Mrs. Doris Daniel and Mrs.

Rosalyn Kyles, Negro citizens of the City of Little Rock,

Pulaski County, Arkansas, instituted a class action in the

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas against Euell Paul, Jr., individually and as owner

of Lake Nixon Club, Pulaski County, Arkansas (A. 2-3).

The petitioners claimed that the Lake Nixon Club was

depriving them, and Negro citizens similarly situated, of

rights, privileges and immunities secured by (a) the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States;

(b) the Commerce Clause of the Constitution; (c) Title II

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C. §2000a), pro

viding for injunctive relief against discrimination in places

of public accommodation; and (d) 42 U. S. C. §1981, pro

viding for the equal rights of citizens and all persons

within the jurisdiction of the United States (A. 2). The

complaint alleged the Lake Nixon Club pursues a policy

of racial discrimination in the operation of its facili

ties, services and accommodations; petitioners prayed for

injunctive relief (A. 4-5).

On August 3, 1966, Mr. Euell Paul, Jr., answered the

complaint (A. 6-7). At trial, Mrs. Paul was made a party

defendant without objection (263 F. Supp. at 414). After

trial without a jury, the district court, on February 1,

1967, held that the Lake Nixon Club is not a place of

public accommodation within the contemplation of the

Civil Rights Act and that its operations do not affect com

6

merce, and dismissed the complaint with prejudice (263 F.

Supp. at 420). The petitioners filed notice of appeal to

the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on March 2,

1967 (A. 63).

The United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth

Circuit affirmed the judgment of the district court on May 3,

1968, Judge Heaney dissenting, 395 F.2d 118, 127. On

June 10, 1968, petitioners’ petition for rehearing was

denied.

Lake Nixon Club is a recreational area comprising 232

acres (A. 41) and located about 12 miles west of Little

Eock, Arkansas (Appellee’s Brief in the Court of Appeals,

1). There is a State highway located 5 miles north of Lake

Nixon and a U.S. highway located 5 miles to the south

(Appellee’s Brief in the Court of Appeals, 2).

During each season, approximately 100,000 people avail

themselves of Lake Nixon’s swimming, picnicking, boating,

sun-bathing, and miniature golf (263 F. Supp. at 416).

At Lake Nixon there is a snack bar which sells ham

burgers, hot dogs, milk and sodas for consumption on the

premises (263 F. Supp. at 416). The snack bar is oper

ated by Mrs. Paul’s sister under an oral agreement whereby

the parties share the profits from the snack bar (A. 32). In

1966 the gross receipts from food sales accounted for al

most 23% of the total gross receipts ($10,468.95 out of a

total of $46,326.00) (A. 13, 63).

The equipment of Lake Nixon includes two juke boxes

manufactured out of Arkansas (263 F. Supp. at 417); 15

aluminum paddle boats leased from an Oklahoma com

pany, and a surfboard or yak purchased from the same

company (A. 28-29). The rental cost of the paddle boats

is based on a percentage of the profits realized from their

rental to patrons of Lake Nixon (A. 28).

7

Lake Nixon Club was advertised in the following media:

(a) once in 1966 in Little Rock Today, a monthly publica

tion distributed free of charge by Little Rock’s leading

hotels, chambers of commerce, motels and restaurants to

their guests, newcomers and tourists; (h) once in 1966 in

the Little Rock Air Force Base publication; (e) and three

days each week from May through September, 1966, over

radio station KALO (A. 12, 96; 263 F. Supp. at 417-418). A

typical radio announcement stated:

“Attention all members of Lake Nixon. In answer to

your requests, Mr. Paul is happy to announce the Sat

urday night dances will be continued . . . Lake Nixon

continues their policy of offering you year-round en

tertainment. The Villagers play for the big dance Sat

urday night and, of course, there’s the jam session

Sunday afternoon . . . also swimming, boating, and

miniature golf . . . ” 395 F.2d at 130, n. 10 (dissenting

opinion).

On July 10, 1966, the petitioners sought admission to Lake

Nixon (A. 37-38). The district court found they were re

fused admission because they are Negroes (263 F. Supp.

at 418) and concluded Lake Nixon Club is not a private

club within the contemplation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

but is a facility open to the white public in general (263

F. Supp. at 418).

Summary o f Argument

Lake Nixon Club is a 232 acre site for public amusement

and recreation, located just outside of Little Rock, Ar

kansas, open to the white public in general but excluding

blacks. In addition to such activities as swimming, boat

ing, picnicking and miniature golf, Lake Nixon Club con

tains a snack bar selling food for consumption on the prem

8

ises. Lake Nixon advertises its entertainment on radio and

in magazines directed to tourists. Because the snack bar,

which serves Lake Nixon’s patrons, offers to serve inter

state travelers as members of the general public and

serves or sells food and other products, which have moved

in commerce, the whole of Lake Nixon is subject to Title II

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Lake Nixon Club is also a place of entertainment affect

ing commerce within the scope of §201 (b)(3) and (c)(3 )

because its patrons are entertained by the activities of

others who enjoy the establishment’s recreational facilities.

The legislative history of Title II supports the view that

Congress sought to encompass places of public amusement

like recreational areas within the statute. Furthermore,

Lake Nixon is subject to §201(c)(3) because it purchases

and leases recreational equipment from out-of-state con

cerns and makes available to its patrons facilities for en

tertainment manufactured outside of Arkansas.

Lake Nixon is also barred from discriminating against

blacks by the equal contractual and property rights guar

antees of 42 U. S. C. §§1981 and 1982. These statutes, de

rived from the 1866 Civil Rights Act, cover the right of

Negroes not to be denied the right to contract and to use

property of a place of public amusement. Sections 1981

and 1982 stand independent of the provisions of Title II

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The legislative history of

§§1981 and 1982 supports the view that these statutes were

designed to eradicate racial discrimination in places of

public accommodation.

9

ARGUMENT

I.

Lake Nixon Club, a Place o f Public Accommodation,

Which Offers to Serve Interstate Travelers and Provides

Food, Facilities for Entertainment, and Other Products

Which Have Moved in Commerce, Is Barred From Ex

cluding Petitioners by Title II o f the 1964 Civil Rights

Act.

For reasons stated in greater detail below, Lake Nixon

Club is a place of public accommodation within the coverage

of Title II of the 1961 Civil Rights Act on both of the follow

ing grounds:

1. A snack bar on the premises serves a substantial

amount of food that has moved in commerce and sells

or offers to sell food to all patrons of Lake Nixon, in

cluding interstate travelers. Section 201(b)(4) and

(c)(4 ).

2. Lake Nixon is a place of entertainment custom

arily presenting sources of entertainment which move

in commerce. Section 201(b)(3) and (c)(3 ).

A. Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act Applies to the Whole

of Lake N ixon B ecause of Its Lunch C ounter’s Operations.

It is not disputed that Lake Nixon’s snack bar is princi

pally engaged in selling* food for consumption on the

premises of Lake Nixon,1 making the snack bar subject to

1 The district court erroneously concluded that the test under

§201 (b) (2) was whether the “ establishment” was “ ‘principally

engaged’ in the sale of food for consumption on the premises” ;

having concluded that Lake Nixon Club was not principally en

gaged in selling food, the district court held that §201 (b) (2) did

not apply. 263 F. Supp. at 419. The district court’s holding mis

construes the language and meaning of §201 (b) (2) that an estab

10

§201 (b )(2 ). Because the snack bar offers to serve inter

state travelers and serves or sells food and other products

which have moved in commerce, the whole of Lake Nixon is

subject to §201(c)(2) and (c)(4 ), and thus barred from

excluding patrons, as here, on racial grounds.

Lake Nixon Club offers to serve interstate travelers by

the mere fact that it is open, as the district court found,

to the white public in general. 263 F. Supp. at 418. Section

201(c) (2) covers an establishment if “ . . . it serves or offers

to serve interstate travelers . . . ” It is plain from the

language that there need be no showing that interstate

travellers were actually served; an offer is sufficient.

Wooten v. Moore, 400 F.2d 239, 242 (4th Cir. 1968).

The district court misconceived the issue by finding no

evidence that Lake Nixon “ ever tried to attract interstate

travelers as such.” 263 F. Supp. at 418 (emphasis added).

The Eighth Circuit compounded the error by holding,

“ There is no evidence that any interstate traveler ever

patronized this facility, or that it offered to serve inter

state travelers . . . ” 395 F.2d at 127. Where an establish

ment like Lake Nixon advertises its facilities on radio and

in magazines for tourists and servicemen, charging only a

token 250 membership fee, what is important is whether

Lake Nixon prohibits interstate travelers from using its

facilities.

Furthermore the district court, sitting near Lake

Nixon in Little Bock, concluded “ it is probably true that

some out-of-state people” have visited Lake Nixon. 263

F. Supp. at 418. Under these circumstances, Lake Nixon

lishment like a restaurant or a lunch counter is covered if such

eating facility is principally engaged in selling food for consump

tion on its premises or on the premises, for example, of a retail

establishment where the eating facility is located. Fazzio Real Es

tate Co. v. Adams, 396 F.2d 146, 149 (5th Cir. 1968).

11

offers to serve interstate travelers within the meaning of

§201 (c) (2). Hamm v. Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964);

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises Inc., 394 F.2d 342 (5th

Cir. en banc, 1968).

In the district court the owners of Lake Nixon suggested

it was a private club within the exemption of §201 (e). But

every judge who has considered this ease has found that

Lake Nixon is open to members of the white race in general

for profit and thus not a private club. 263 F. Supp. at 418;

395 F.2d at 123, 130.2

Lake Nixon is also subject to 201(c) (2) because a substan

tial portion of the food and other products sold at the

snack bar have moved in commerce. “ Substantial” means

more than minimal. 395 F.2d at 124; Gregory v. Meyer, 376

F.2d 509, 511 n. 1 (5th Cir. 1967).

The only food served at the snack bar consists of ham

burgers, hot dogs, soft drinks, and milk, 263 F. Supp. at

416. The district court took judicial notice that the princi

pal ingredients of bread are produced outside of Arkansas

and that some ingredients of soft drinks probably origi

nated outside of Arkansas. 263 F. Supp. at 418. The

Eighth Circuit asserted, however, that bread ingredients

would not constitute a substantial portion of the food

served and that the milk used was obtained in Arkansas.

395 F.2d at 124. But to ascribe to “ substantial” any mean

ing other than “ more than minimal” forces the Court and

2 Lake Nixon contains none of the indicia of a private club such

as a membership committee, self-government, ownership of assets

by the membership, and social as opposed to profit-making objec

tives. Mr. and Mrs. Paul own Lake Nixon; they exercise their own

judgment in admitting or excluding “members” ; there is no list

of “members” and no address required on membership cards;

radio and magazine notices are given to ‘‘members” of Lake Nixon’s

entertainment; a nominal 25j fee is charged for “membership” ;

the Pauls operated Lake Nixon for profit. 263 F. Supp. at 416-18.

12

counsel to reflect on obvious facts such as hamburgers and

hot dogs are served in a bun or other piece of bread. Since

the snack bar sold many hamburgers and soft drinks (A.

31, 34), three of the four food items sold at the snack bar,

including the two major products, contained ingredients

originating outside of Arkansas. That 75% of the types of

foodstuffs sold contain out-of-state ingredients would seem

substantial by any reasonable test. Katsenbach v. McClung,

379 U.S. 294, 296-97 (1964) (46% is substantial); Codogan

v. Fox, 266 F. Supp. 866 (M.D. Fla. 1967) (23-30% is sub

stantial). Having established this, it seems that a more

common sense approach, i.e., telling at a glance whether a

more than de minimis test lias been satisfied, is all that

should be required in the interest of the policy of the law

and judicial economy.

Because the snack bar is physically located within the

premises of Lake Nixon and holds itself out as serving

patrons of Lake Nixon, all of its facilities and privileges

comprise a place of public accommodation within §201

(b ) (4) and ( c ) (4).

Both the district court and the court of appeals held that,

because the gross income from food sales constitutes a rela

tively small percentage of the total gross income (23%)

and the sale of food is merely an adjunct to the Pauls’

principal purpose of providing recreational facilities, Lake

Nixon is a single unit operation and not covered by §201

(b )(4 ). Apparently the Eighth Circuit requires for cover

age under Title II at least two establishments under sepa

rate ownership. See 395 F.2d at 123. This holding is in

conflict with the decision of every other court which has

considered this subsection.

In Fazzio Real Estate Co. v. Adams, 396 F.2d 146 (5th

Cir. 1968), the court held that where the operators of a

bowling alley also operated a snack bar for the patrons

13

of the bowling alley, the entire establishment was covered

by this subsection. Income from the sale of food and beer

in Fazzio represented 23% of the total gross income; in

come from the sale of food alone represented 8 to 11% of

the total gross income. The court held that even 8 to 11%

could not be considered insignificant and explicitly rejected

the substantial business purpose test of the Eighth Circuit,

compare 396 F.2d at 150 with 395 F.2d at 123. The Fifth

Circuit stated, 396 F.2d at 149:

The Act contemplates that the term “ establishment”

refers to any separately identifiable business operation

without regard to whether that operation is carried on

in conjunction with other service or retail sales opera

tions and without regard to questions concerning

ownership, management or control of such operations.3

Even under its own rule that Title II covers only sepa

rately managed but physically connected establishments,

the Eighth Circuit erred in failing to find the snack bar’s

operations made Lake Nixon a public accommodation with

in the coverage of Title II. The evidence is that the snack

bar is a separate enterprise managed by Mrs. Paul’s sister

pursuant to an oral contract whereby the Pauls and Mrs.

Paul’s sister share the profits from food sales.

3 In Evans v. Laurel Links, Inc., 261 F. Supp. 474 (E.D. Ya.

1966), the court held an entire golf course within the coverage of

Title II, because the operators of the golf course maintained a

lunch counter for the patrons of the course. Income from food

sales constituted 15% of the total gross income of the golf course.

See also Hamm v. Bock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964); Scott v. Young,

12 Race Rel. L. Rep. 428 (E.D. Va. 1966) (recreational area with

snackbar). The legislative history supports the majority rule. The

Report of the House Judiciary Committee states that subsection

(b) (4) “would include, for example, retail stores which contain

public lunch counters otherwise covered by Title II” . H. R. Rep.

No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. 20 (1963).

14

B. Lake Nixon Is a Place of Entertainment As Defined by

Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Lake Nixon also is a place of entertainment within the

contemplation of Title II and we submit that this Court

should so hold. The snack bar might be eliminated for the

purpose of removing Lake Nixon from Title II coverage

and then further litigation would be necessary to determine

whether it is a place of entertainment. This possibility is

not fanciful: in a companion case involving a similar recrea

tional area, all sales of food were discontinued after peti

tioners instituted an action under Title II, 263 F. Supp.

at 417. In addition, the conflict between the Eighth Cir

cuit’s construction of “place of entertainment” and that of

the Fifth Circuit in Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc.,

394 F.2d 342 (5th Cir. en banc, 1968), should be resolved by

this Court.

The Eighth Circuit held Lake Nixon was not a “place of

entertainment” , because the Court found a total lack of

evidence that its activities or entertainment moved in com

merce, 395 F.2d at 125. The district court, defining “place

of entertainment” to mean an establishment where the

patrons are spectators or listeners and their physical par

ticipation is non-existent or minimal, held that Lake Nixon

is not within this definition (263 F. Supp. at 419).

In Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., supra, the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, sitting en banc,

overruled the prior decision of a three-judge panel (re

ported at 391 F.2d 86), and held that Fun Fair amusement

park in Baton Bouge, La., is a place of entertainment

within the coverage of Title II. Noting that it was not nec

essary to its decision, the Court held that even under a nar

row construction of “place of entertainment” to include

only places which present exhibitions for spectators, Fun

15

Fair is a covered establishment because “many of the

people who assemble at the park come there to be enter

tained by watching others, particularly their own children,

participate in the activities available” , 394 F.2d at 348.

Swimming, boating, picnicking, sun-bathing and dancing

at Lake Nixon are certainly as much, if not more, spectator

activities as ice-skating and “kiddie rides” at Fun Fair, see

394 F.2d at 348.

The overriding* purpose of Title II was to eliminate dis

crimination in those facilities which were the focal point

of civil rights demonstrations. Hearings on II. R. 7152

Before the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 88th Gong., 1st

Sess., ser. 4, pt. 4, at 2655 (1963) (Testimony of Attorney

Gen’l Kennedy). President Kennedy clearly intended that

recreational areas and other places of amusement be cov

ered. Hearings on Miscellaneous Proposals Regarding Civil

Rights Before Subcomm. No. 5 of the House Comm, on the

Judiciary, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., ser. 4, pt. 4, at 1448-1449,

2655 (1963). Facilities which were the focal point of dem

onstrations were consistently identified in both the Senate

and House hearings as lodging houses, eating places, and

places of amusement or recreation. 110 Cong*. Rec. 7383

(1964) (Remarks of Sen. Young). While the Senate was

debating the Act, there were demonstrations at the Gwynn

Oak Amusement Park in Maryland; Senator Humphrey

stated that this was proof of the need for this Act. 109

Cong. Rec. 12276 (1963).

Under either a narrow or a liberal construction of “place

of entertainment” , coverage depends on whether Lake

Nixon customarily presents sources of entertainment which

move in commerce. The Eighth Circuit could not discern

any evidence that any source of entertainment customarily

presented by Lake Nison moved in interstate commerce,

395 F.2d at 125.

16

In fact, “ sources of entertainment” were intended to

include equipment. In a discussion of §201 (c)(3 ), Senator

Magnuson, floor manager of Title II, pointed out that “ es

tablishments which receive supplies, equipment or goods

through the channels of interstate commerce . . . narrow

their potential markets by artificially restricting their

patrons to non-Negroes, the volume of sales and therefore,

the volume of interstate purchases will be less,” 110 Cong.

Rec. 7402 (1964) (emphasis added). In the discussion of

the demonstration at the Gwynn Oak Amusement Park,

Senator Humphrey believed that the park would be covered

by the Act in part because he was “confident that mer

chandise and facilities used in the park were transported

across State lines,” 109 Cong. Rec. 12276 (1963).

Lake Nixon purchases and leases its boats from an Okla

homa company. The Pauls rent two juke boxes which were

manufactured outside Arkansas and which play records

manufactured outside Arkansas. In view of these facts the

Eighth Circuit is in direct conflict with Fifth Circuit’s deci

sion in Miller. The Miller Court relied in part on the fact

that 10 of the 11 “kiddie rides” at the park were purchased

from out of state, 394 F.2d at 351, to find an effect on

commerce. But the Court also concluded that even under

a narrow construction of the Act, since Fun Fair is located

on a major highway and does not geographically restrict

its advertising, the logical conclusion is that a number of

the patrons, whose activities may entertain, have moved

in commerce, 394 F.2d at 349. The same circumstances

which make it reasonable to assume that some interstate

travelers will accept Lake Nixon’s offer to serve the gen

eral public make it reasonable to assume that some of

Lake Nixon’s patrons have moved in commerce.

The Eighth and Fifth Circuits are also in conflict as to

the meaning of “move in commerce” . The district court

17

found that Lake Nixon’s operations do not affect commerce

on the ground that, although the boats, juke boxes and rec

ords have moved in commerce, they do not now move, 263

F. Supp. at 420. The court concluded that because the

phrase, “has moved” , appears in the section concerning eat

ing facilities, Congress must have intended to limit the

section concerning places of entertainment to sources which

“move” , and therefore sources of entertainment which have

but no longer move, are not covered, 263 F. Supp. at 420.

The Fifth Circuit, on the other hand, expressly concluded

in Miller that Congressional use of the present tense of

“move” was not intended to exclude other tenses, 394 F.2d

at 351-52.

The legislative history supports the conclusion of the

Fifth Circuit. The Report of the Senate Committee on

Commerce refers within a single paragraph to “ sources of

entertainment which move in interstate commerce” and

“ entertainment that has moved in interstate commerce” , as

within the contemplation of §201(e)(3). 8. Rep. No. 872

on 8 . 1732, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess. 3 (1964). See also 110

Cong. Rec. 6557 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Kuchel). In ad

dition, a proposal to amend §2Gl(c)(3) to read “ sources of

entertainment which move in commerce and have not come

to rest within a state” was rejected. 110 Cong. Rec. 13915,

13921 (1964). The subsequent debate indicates that Con

gress intended the bill to reach businesses which individu

ally had a minimal or insignificant impact on interstate

commerce. 110 Cong. Rec. 13924 (1964).

18

II.

The Equal Right to Make and Enforce Contracts and

to Have an Interest in Property, Guaranteed by 42

U.S.C. §§1981 and 1982, Includes the Right o f Negroes

to Have Access to a Place o f Public Amusement.

The first sentence of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, en

acted pursuant to the Thirteenth Amendment, provided,

inter alia, for citizens to have the same right to make and

enforce contracts and have an interest in property as is

enjoyed by white citizens. These rights are now embodied

in 42 U. S. C. §§1981 and 1982. Negro petitioners have been

denied these rights because the Pauls barred them from

becoming 25 ̂ “members” of Lake Nixon solely on racial

grounds. The Lake Nixon membership fee is in effect a

contract, like the purchase of a ticket, entitling one to use,

for a time, the real and personal property on Lake Nixon’s

232 acres. See Griffin v. Southland Racing Corp., 236 Ark.

872, 370 S.W.2d 429 (1963); Vallee v. Stengel, 176 F.2d

697 (3rd Cir. 1949). Denial of these contractual and prop

erty rights on racial grounds violates rights secured by the

1866 Civil Rights Act. See Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409, 426, 436, 439-41 (1968). As this Court held just last

term, “At the very least, the freedom that Congress is em

powered to secure under the Thirteenth Amendment in

cludes the freedom to buy whatever a white man can

buy . . ” Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, 392 U.S. at 443 (em

phasis added). Neither of the courts below considered the

applicability of Jones since it was decided subsequent to

the Eighth Circuit’s denial of rehearing.

For reasons essentially similar to those holding §1982

independent of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U. S. C.

§§3601-3631—the principal reasons being differences in cov

erage between the two statutes and no Congressional pur

19

pose to limit §1982-—petitioners submit that §§1981 and

1982 provide rights independent of Title II of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, 42 U. S. C. §2000a.4 See Jones v. Mayer

Co., supra, 392 U.S, at 413-17. Where racial discrimination

between blacks and whites is alleged, the great advantage

of applying the sweeping and unambiguous language of

§§1981, 1982 is that no complex statutory tests for cover

age need be applied as in the ca«e of Title II of the 1964

Civil Rights Act.5 6

In this case a threshold question on the applicability of

§§1981 and 1982 is whether these statutes are properly be

fore the Court. Section 1981, guaranteeing equal con

tractual rights, was specifically pleaded in the complaint

(A. 2, 5), and thus its applicability is properly to be de

termined. Section 1982 was not pleaded below but this

does not bar petitioners from relying on it here because

this Court has made clear that the “mere failure” to raise

a constitutional or statutory question “ prior to the an

nouncement of a decision which might support it cannot

prevent a litigant from later invoking such a ground”

Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130,142-143 (1967);

Thorpe v. Housing Authority, 37 U.S.L.W. 4068, 4072 and

4 Among other points of difference between §§1981, 1982 and

Title II are these: (a) Sections 1981, 1982 contain no exceptions

whereas Title II covers only places of public accommodation affect

ing commerce as defined; (b) Title II prohibits discrimination

based on religion and national origin whereas §§1981, 1982 prohibit

only treatment different from white citizens; (c) Title II makes no

distinction between citizens and persons—all are entitled to be free

from discrimination, whereas §1982 guarantees to citizens property

rights equal to white citizens, No intent to modify §§1981 or 1982

could be found in the legislative history of Title II.

6 Much litigation has concerned simply Title II’s requirement of

“affecting commerce.” See e.g., Fazzio Beal Estate Co. v. Adams,

•396 F.2d 146 (5th Cir. 1968); Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 256 F. Supp. 941 (D.S.C. 1966), rev’d, 377 F.2d 433 (4th

Cir. 1967), mod. and aff’d on oth. gds., 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

20

accompanying notes (U.S. Jan. 13,1969). Furthermore, this

precise issue was before this Court last term in Sullivan v.

Little Hunting Park, 392 U.S. 657 (1968) where this Court

vacated the judgment of the Virginia Supreme Court of

Appeals and remanded the case for further consideration in

light of Jones v. Mayer Co., supra, even though the Sullivan

petitioners did not rely on §1982 in the Virginia courts.

This case, involving as it does the contractual and prop

erty rights of blacks to use Lake Nixon Club is, therefore,

controlled by the language of §§1981 and 1982 requiring

equal rights. Any intimation to the contrary in the Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 16-18 (1883) has been superseded

by the approval on Thirteenth Amendment grounds of the

1866 Act in Jones, 392 U.S. at 426, 436, 439-41. This Court’s

holding in Jones and the legislative history of the 1866 Act,

from which §§1981 and 1982 are derived,6 demonstrate a 6

6 Much of the legislative history of the 1866 Civil Rights Act

which this Court found persuasive in Jones is applicable here to

show that the Act was intended to make blacks the practical equal

of whites. 392 U.S. at 420-40 and accompanying notes. The spon

sor of the 1866 Act, Senator Trumbull, repeatedly affirmed the

Act’s intention to give blacks the rights to go or come at pleasure

and to buy and sell without discrimination. Cong. Globe, 39th

Cong., 1st Sess. 43, 322, 475, 599. The opponents of the Act and

its companion bill, the Freemen’s Bureau Bill, pointed out the

Act would permit commingling of whites and blacks in hotels,

theaters and public conveyances. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

at 541 (remarks of Rep. Dawson); id. at Appendix 183, 936 (re

marks of Sen. Davis); id. at Appendix 69 (remarks of Rep. Rous

seau). No one disputed this view. Furthermore, in the early years

following the Act’s passage, the common view of its friends and

enemies that it applied to public accommodations and conveyances

was generally accepted by various courts. IT. Flack, The Adoption

of Fourteenth Amendment 46-47, 52-54 (1908) ; Coger v. The North

West Union Packet Go., 37 Iowa 145, 153-54 (1873). Cf. “ That the

[1866 Civil Rights] bill would indeed have so sweeping an effect

[in breaking down all discrimination between whites and blacks]

was seen as its great virtue by its friends and as its great danger

by its enemies but was disputed by none.” Jones v. Mayer Co.,

supra, 392 U.S. at 433 (footnotes omitted).

2 1

Congressional purpose to outlaw racial discrimination

where, as here, access to public accommodations concerns

rights of contract and property.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the judgment below should

be reversed or, in the alternative, reversed and remanded

for reconsideration in light of Jones v. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968).

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

N orman C. A m aker

C onrad K. H arper

N orman J . Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

Attorneys for Petitioners

M EIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y C. «*^P=>219