Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Banks Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 2003

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Banks Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, 2003. 3b0a7e11-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9a4ce99a-08ce-40c3-9917-5a72fa89f4b1/commissioner-of-internal-revenue-v-banks-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

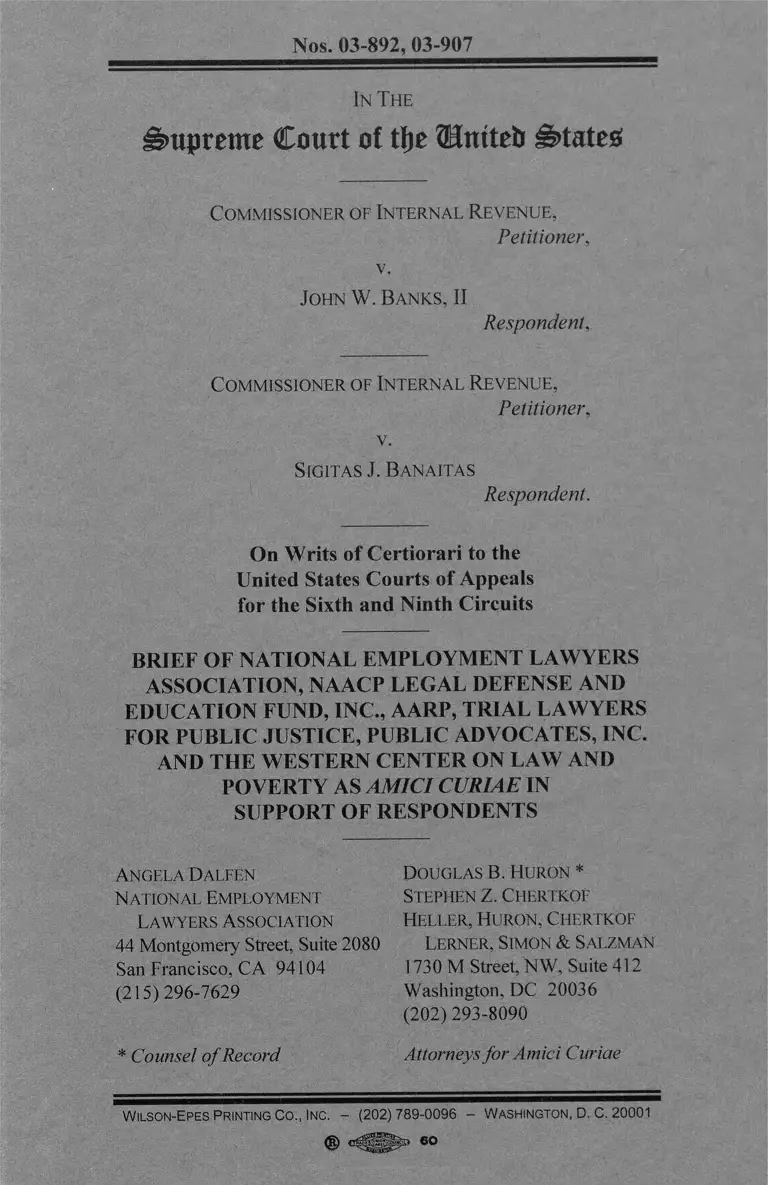

Nos. 03-892, 03-907

In The

Supreme Court of tfje dntteb States!

C o m m issio n e r o f In t er n a l R e v e n u e ,

Petitioner,

v.

J ohn W. B a n k s , II

Respondent,

C o m m issio n e r of In t e r n a l R e v e n u e ,

Petitioner,

v.

SlGITAS J. BANAITAS

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the

United States Courts of Appeals

for the Sixth and Ninth Circuits

BRIEF OF NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAWYERS

ASSOCIATION, NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC., AARP, TRIAL LAWYERS

FOR PUBLIC JUSTICE, PUBLIC ADVOCATES, INC.

AND THE WESTERN CENTER ON LAW AND

POVERTY AS AMICI CURIAE IN

SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Angela Dalfen

N ational E mployment

Lawyers A ssociation

44 Montgomery Street, Suite 2080

San Francisco, CA 94104

(215)296-7629

* Counsel of Record

Douglas b . Huron *

Stephen Z. Chertkof

Heller , Huron , Chertkof

Li.RNi R, Simon & Salzman

1730 M Street, NW, Suite 412

Washington, DC 20036

(202)293-8090

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

W ilson-Epes Printing Co., Inc. (202) 789-0096

60

Washington, D. C. 20001

V ictoria w . N i

Trial Law yers for Public

Justice, P.C.

One Kaiser Plaza, Suite 275

Oakland, CA 94612

R ichard A. Marcantonio

Public Advocates, In c .

131 Steuart Street, Suite 300

San Francisco, CA 94105

R ichard A. Rothschild

Western Center on Law

and Poverty

3701 Wilshire Boulevard,

Suite 208

Los Angeles, California 90010

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

N orman J. Chachkin

Robert h . Stroup

Naacp Legal Defense &

Educational Fund , In c .

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

Leslie M. Proll

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund , In c .

1444 I Street, NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

Thomas W. Osborne

AARP

601 E Street, NW

Washington, DC 20049

Co-Counsel for Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................................... iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.................................... 1

STATEMENT................................................................. 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT...................................... 3

ARGUMENT.................................................................... 7

I. ATTORNEYS’ FEES RECEIVED BY

COUNSEL IN STATUTORY FEE CASES

ARE NOT INCOME TO THE PLAINTIFF.... 7

A. The Private Attorney General...................... 7

B. The Tax Problem in Statutory Fee Cases.... 8

C. The Assignment of Income Doctrine Does

Not Apply to Statutory Fees........................ 11

1. The Assignment of Income Doctrine..... 11

2. The Inapplicability of the Doctrine to

Statutory Fees......................................... 12

D. Porter v. A ID ................................................ 14

E. The Effect of Statutory Fee Shifting on

Banks............................................................. 17

II. ORDINARY CONTINGENT FEES ARE

NOT INCOME TO THE PLAINTIFF.............. 19

A. The Split in the Circuits................................ 20

B. The Dispositive Nature of the Joint Ven

ture Analogy........................... 21

1. Kenseth.................................................... 22

2. The Economic Realities......................... 23

Page

(0

TABLE OF CONTENTS-Continued

Page

3. The Contingent Fee Lawyer as Joint

Venturer................................................... 25

CONCLUSION................................................................ 27

APPENDIX...................................................................... la

Ill

Arneson v. Sullivan, 958 F. Supp. 443 (E.I). Mo.

1996)..................................................................... 16

Banaitis v. Commissioner, 340 F.3d 1074 (9th

Cir. 2003)...................................................2 .3 .7 . 20.21

Banks v. Commissioner. 345 F.3d 373 (6th Cir.

2003)......................................................................passim

Bari in v. United States, A3 F.3d 1451 (Fed. Cir.

1995)..................................................................... 20

Benci-Woodward v. Commissioner. 219 F.3d 941

(9th Cir. 2000). cert, denied, 531 U.S. 1112

(2001) .................................................................................... 21

Biehl v. Commissioner, 351 F.3d 982 (9th Cir.

2003).................................................................... 9

Blanchard v. Bergeron. 489 U.S. 87 (1989)......... 4. 5, 13

Blum v. Slenson, 465 U.S. 886 (1984)........ 4. 5. 8, 12. 13

Burlington Industries. Inc. v. Ellerth. 524 U.S.

742 (1998)............................................................ 18

City o f Riverside v. Rivera. 477 U.S. 561 (1986).. 4. 10

Estate o f Clarks v. United States, 202 F.3d 854

(6th Cir. 2000)..................................................... 20

Coady v. Commissioner, 213 F.3d 1187 (9th Cir.

2000) , cert, denied. 532 U.S. 972 (2001)......... 21

Cotnam v. Commissioner, 263 F.2d 119 (5th Cir.

1959)..................................................................... 3

Dashnaw v. Pena. 12 F.3d 1112 (D.C. Cir. 1994).. 16

Davis v. Commissioner. 210 F.3d 1346 (11th Cir.

2000).................................................................... 20

EEOC v. Joe's Stone Crab. Inc., 15 F. Supp. 2d

1368 (S.D. Fla. 1998)......................................... 16

EEOC v. Shell Oil Co.. 466 U.S. 54 (1984)......... 5.18

Evans v. JeffD ., 475 U.S. 717 (1986)................... 14

Foster v. United States, 249 F.3d 1275 (11th Cir.

2001) ....................................................................................................... 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

FEDERAL CASES Page

IV

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).. 10

Helvering v. Horst, 311 U.S. 112 (1940)...3. 5, 12. 14, 24

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983)............ 13

Hukkanen-Campbell v. Commissioner, 274 F.3d

1312 (10th Cir. 2001), cert, denied, 535 U.S.

1056(2002).......................................................... 20,22

Jordan v. CCH, Inc., 230 F. Supp. 2d 603 (E.D.

Pa. 2002)....................................................... 15

Kay v. Ehrler, 499 U.S. 432 (1991)......................... 5,14

Kenseth v. Commissioner, 259 F.3d 881 (7th Cir.

2001)....................................................20, 22. 23. 24. 26

Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111 (1930).................3, 5, 12, 24

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961)...................... 19

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390

U.S. 400(1968)................................................... 1 .3 ,8

O'Neill v. Sears Roebuck & Co., 108 F. Supp. 2d

443 (E.D. Pa. 2000)............................................. 15

Porter v. Director, Agency for International

Development, 293 F. Supp. 2d 152 (D.D.C.

2003) .................................................................. 4

Raymond v. United States, 355 F.3d 107 (2d Cir.

2004) .................................................................. 20

Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway

Co., 749 F.2d 1451 (10th Cir. 1984)...............’.. 15

Sinyard v. Commissioner, 268 F.3d 756 (9th Cir.

2001), cert, denied, 538 U.S. 904 (2002)........... 12

Srivastava v. Commissioner, 220 F.3d 353 (5th

Cir. 2000)............................................................. 20

Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288 (1989).................... 6, 19

Venegas v. Mitchell, 495 U.S. 82 (1990)...4, 5, 7, 8. 11, 13

White v. New Hampshire Department o f Employ

ment Security, 455 U.S. 445 (1982)..................... 9

Young v. Commissioner, 240 F.3d 369 (4th Cir.

2001)..................................................................... 20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

STATE CASE Page

Blaney v. 1AM, 87 P.3d 757 (S.Ct. Wash. 2004)... 16

FEDERAL STATUTES

26 U.S.C. § 104(a)(2)............................................ 18

26 U.S.C. § 55(b)( 1 )(A)(i)..................................... 10

26 U.S.C. § 56(b)(l)(A)(i)..................................... 10

26 U.S.C. § 61 (a)( 13)..................................... 6. 21.24. 25

26 U.S.C. § 62(a)(2)(A)......................................... 9

26 U.S.C. § 67 ....................................................... 9

26 U.S.C. §68 ........................................................ 9

26 U.S.C. § 104(a)(2)............................................ 2

26 U.S.C. § 702 ...................................................... 21

26 U.S.C. § 761(a)................................................6 .21.24

29 U.S.C. § 216(b)................................................. 22

29 U.S.C. § 626(b)................................................. 22

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .....................................................1.2. 17

42 U.S.C. § 1981 a(b)(3)......................................... 10.11

42 U.S.C. § 1983.....................................................1. 2. 17

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-3(b).......................................... 7

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)........................................... 2. 7. 17

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ................................................ 2. 7. 8. 17

FEDERAL REGULATION

26 C.F.R. § 1.62-2(c)(4) (2004)............................. 9

MISCELLANEOUS

Adam Liptak. "Tax Bill Exceeds Award to

Officer in Sex Bias Case.” New York Times

(August 11.2002)....................................... 10

Richard Posner. Economic Analysis o f Law

(5th ed. 1998)..................................................... 6 .23,26

Laura Sager and Stephen Cohen, "How the

Income Tax Undermines Civil Rights Law. " 73

S. Cal. L. Rev. 1075 ........................................... 9.10

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE1

All amici here, either organizationally or through their

members, represent individuals under Federal fee shifting

statutes, including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

the Equal Pay Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983. the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act. the Rehabilitation Act

of 1973. the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Family

and Medical Leave Act. The payment of attorneys' fees in

such litigation is contingent in the sense that the defendant

only pays fees if the plaintiff prevails, but the fee award is

separate from judgment on the merits. This is unlike the

situation in “ordinary” contingent fee cases, where fees are

apportioned from the merits judgment, with lawyer and client

each taking a share.

In fee shifting cases under civil rights statutes, the relief

sought may be exclusively, or predominantly, injunctive.

Indeed, the only money awarded in some cases may be the

attorneys' fees themselves. If the plaintiffs in these or similar

cases are required to pay taxes on fees that go to their

lawyers, they will lose money by winning a lawsuit. Even the

most meritorious civil rights claims will not be pursued, and

the fundamental goal of fee shifting—encouraging citizens to

act “as a "private attorney general,' vindicating a policy that

Congress considered of the highest priority,” Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402 (1968)—

will be nullified. All amici share an interest in seeing that this

does not occur.

1 The parties have consented to the filing of this brief, and their letters

of consent are on file with the Clerk. Counsel for amici curiae certify that

this brief was not written, in whole or part, by counsel for a party, and that

no person or entity, other than amici curiae and counsel, made a monetary

contribution to the preparation or submission of the brief. Supreme Court

Rule 37.6.

Amici also have an interest in the plaintiffs tax liability for

fees received by lawyers under ordinary contingent fee agree

ments, because such agreements may provide the only vehicle

for financing litigation on behalf of impecunious individuals,

especially if fee shifting statutes are not available. Fuller

statements of interest for all amici are included in the appen

dix to this brief.

STATEMENT

These consolidated cases both involve the tax treatment

of fees paid to plaintiff s counsel in employment litigation

undertaken under a contingent fee agreement. Contrary to

the Solicitor General’s assumption, however, there are

significant differences between the two cases, requiring

different modes of analysis.“

In No. 03-892, respondent Banks originally sued his

employer under both Federal and state law. But by the time

the case settled for $464,000 ($150,000 of which went to

counsel), only the three Federal claims remained viable,

arising under Title VII and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983. Banks

v. Commissioner, 345 F.3d 373, 379 (6th Cir. 2003). All three

of these claims were subject to statutory fee shifting. See

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (Title VII). and̂ 42 U.S.C. § 1988

(§§ 1981, 1983).

In No. 03-907, in contrast, respondent Banaitis pursued

two common law Oregon tort claims. Banaitis v. Commis

sioner, 340 F'.3d 1074, 1077 (9th Cir. 2003). Such claims

were not subject to fee shifting. The case ultimately settled

for $8,728,559, of which $3,864,012 was paid to counsel.

Id. at 1078.

‘ As the Solicitor General notes, Brief for Petitioner at 15 n.3, neither

case involves recoveries for “personal physical injuries or physical

sickness,” which are excluded from gross income under 26 U.S.C. §

104(a)(2).

Both the Sixth Circuit in Banks and the Ninth in Banaitis

held that the fees received by counsel should not be treated as

income to the plaintiff. Consequently, those fees were subject

to taxation only as income to the lawyers. The two courts

employed different rationales. The Ninth Circuit viewed state

lien law as dispositive, as in Cotnam v. Commissioner. 263

F.2d 119 (5th Cir. 1959), and stressed that Oregon law was

comparable to that in Alabama (as analyzed in Cotnam) in

granting superior rights to lawyers. 340 F.3d at 1082-83. 1 he

Sixth Circuit rejected a “state-by-state” approach, instead

likening Banks' lawyer to a “tenant in common of the orchard

owner [who] must cultivate and care for and harvest the fruit

of the entire tract.” 345 F.3d at 384-85. The Sixth Circuit did

not focus on the fee shifting statutes under which Banks'

claims arose.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In both these cases, the taxpayer derived income from

settlement of a lawsuit against his employer, and in both

cases the underlying litigation featured a contingent tee

agreement between the taxpayer and counsel. In Banks,

however—unlike Banaitis—the settled claims arose under

Federal fee shifting statutes. This distinction is crucial.

1. Whatever the proper result in ordinary contingent

fee litigation, fees awarded by a court under a tee shifting

statute (or paid as part of a settlement) are not income to the

plaintiff. The “assignment of income” doctrine, developed in

cases like Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111 (1930), and Helvering

v. Horst, 311 U.S. 112 (1940), simply has no application to

the statutory fee model, because statutory fees are not intend

ed to liquidate a private debt owed by a plaintiff to counsel.

This Court has explained that a private plaintiff in a civil

rights case acts “as a ‘private attorney general," vindicating a

policy that Congress considered of the highest priority.”

Newman v. Biggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. at 402.

4

Resources are required for successful prosecutions by any

attorney general, public or private, and Congress “enacted the

provision for counsel fees . . . to encourage individuals

injured by racial discrimination to seek judicial relief.” Id.

The “aim” of fee shifting is to encourage meritorious liti

gation by “enabling] civil rights plaintiffs to employ

reasonably competent lawyers without cost to themselves if

they prevail.” Venegas v. Mitchell. 495 U.S. 82, 86 (1990).

A statutory fee case, unlike ordinary contingent fee

litigation, entails two distinct awards, separated temporally:

(1) judgment on the merits, which may be declaratory or

injunctive relief or damages from a jury, followed by

(2) attorneys’ fees awarded by the court. Judicial awards

at "stage 2” are divorced from any private agreements

between plaintiff and counsel, Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489

U.S. 87, 93 (1989), and are intended to produce “fees which

are adequate to attract competent counsel, but which do not

produce windfalls to attorneys.” Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S.

886. 893-94 (1984).

The difference between statutory fees and ordinary

contingent fees is perhaps best illustrated by the eligibility of

pro hono legal organizations for statutory fees at normal

market rates, even though the plaintiff owes them nothing.

Id. at 894. This makes it clear that statutory fees are not

intended to discharge private obligations.

Statutory fees and ordinary contingent fees also differ in

another crucial respect. Unlike ordinary contingent fees,

which are some percentage of the merits recovery, it is not

unusual for a statutory fee award to be larger than the merits

judgment. City o f Riverside v. Rivera. 477 U.S. 561 (1986).

In such cases, if attorneys’ fees are considered income to the

plaintiff, the operation of the Alternative Minimum Tax will

frequently result in a prevailing plaintiffs suffering a net

financial loss. See, e.g., Porter v. Director, Agency for

International Development, 293 F.Supp.2d 152 (D.D.C.

2003) (plaintiff who won a jury verdict of $30,000 plus a tee

award could suffer a post-tax loss of nearly $50,000). The

plaintiff in the worst posture is the one who seeks, and

secures, purely injunctive relief; she receives no money

herself but pays taxes on every dollar that her lawyer is

awarded in fees.

A key objective of fee shifting, however, is to permit

plaintiffs “to employ . . . lawyers without cost to themselves it

they prevail.’' Venegas v. Mitchell, 495 U.S. at 86 (emphasis

added). Including statutory fees in the plaintiffs income

undermines this congressional goal and is not required by

unyielding tax principles. The evils addressed by Lucas v.

Earl and Helvering v. Horst are simply not present in the fee

shifting context. In particular, this is not a situation in which

a plaintiff is assigning his own income to counsel. On the

contrary, the plaintiff himself has no statutory right to the fee

award, even if he is a lawyer, since judicially ordered tees are

intended only for retained counsel. Kay v. Ehrler. 499 U.S.

432 (1991). Nor is it a case of the defendant paying a private

debt owed by plaintiff to counsel, since statutory fees are

independent of private fee agreements. Blum v. Stenson,

supra; Blanchard v. Bergeron, supra. Finally, this is not a

situation in which an amount will go untaxed unless deemed

income to the plaintiff. An award of attorneys’ tees is without

question income to counsel, and counsel pays taxes on it.

The taxpayer's employment claims in Banks arose under

fee shifting statutes, but there was no judicial award of fees

because the case settled. Had Banks gone to trial and

recovered the same amounts—$314,000 from a jury verdict,

followed by a fee award of $150.000—the fees would not

properly be seen as income to him. The tax treatment should

not be affected by the fortuity that these sums were recovered

through settlement. See EEOC v. Shell Oil Co.. 466 U.S. 54.

77 (1984). Otherwise, plaintiffs in fee shifting cases would

be compelled to litigate, rather than settle, simply to enjoy

favorable tax treatment.

A judicial award of attorneys’ fees under a fee shifting

statute is not income to the plaintiff, and fees recovered

through settlement should be treated the same way. The

judgment of the court of appeals in Banks can be affirmed

on this ground alone. Amici recognize that the issue of the

proper tax treatment of statutory fees was not presented to the

Court by the parties, but the Court may consider arguments

only put forward by an amicus, Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S.

288, 300 (1989), and amici request that the Court consider

doing so here.

2. In addition, and in the alternative, fees received by

counsel in ordinary contingent fee cases should not be

deemed the plaintiffs income, either. A lawyer retained on a

contingent basis is in the same economic position as a joint

venturer, “in effect a cotenant of the property represented by

the plaintiff's claim.” Richard Posner, Economic Analysis o f

Law (5th ed. 1998) at 625. See Banks, 345 F.3d at 384-85. A

joint venture is a “partnership” under the Tax Code, 26

U.S.C. § 761(a), and partners are taxed only on their

respective “share of partnership gross income.” 26 U.S.C.

§ 61 (a)( 13).

Unlike a commissioned salesperson, a lawyer paid on a

contingent fee basis— if successful—significantly enhances

the value of the underlying property (i.e., the plaintiffs

claim). And unlike counsel paid on an hourly basis, a

contingent fee lawyer assumes the risk that the venture may

not succeed.

In short, a successful lawyer operating under a contingent

fee agreement both enhances the value of property and

assumes the risk that the property may not be profitable. In

these respects, the lawyer is in the same economic position as

the owner of the property, whether or not a formal co-tenancy

relationship exists. Tax law should recognize this economic

6

7

reality and treat a contingent fee arrangement as a joint

venture, in which the parties are taxed only on their

respective shares of gross income. Both Banaitis and Banks

can be affirmed on this basis.

ARGUMENT

I. ATTORNEYS’ FEES RECEIVED BY COUNSEL

IN STATUTORY FEE CASES ARE NOT IN

COME TO THE PLAINTIFF

An ordinary contingent fee case is “contingent" because

counsel is compensated only if the plaintiff prevails following

trial or if the case settles; the lawyer takes a percentage of

the jury award (or settlement). The archetypal case under a

fee shifting statute is also contingent in the sense that counsel

is not compensated unless the plaintiff prevails. But counsel's

fee does not come from the plaintiffs recovery; rather,

responsibility for payment of the lee is “shifted” to the defen

dant, and the amount is determined by the court in a separate

proceeding after the plaintiff has prevailed on the merits.

A. The Private Attorney General

Statutory fee shifting is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The first modern fee shifting provisions were contained

in Titles II and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. See

42 U.S.C. § 2000a-3(b) (Title II). 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)

(Title VII). Twelve years later, the Civil Rights Attorney's

Fees Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988. broadened the

sweep of statutory fee shifting to embrace a host of other civil

rights law:s.

This Court has said that the “aim” of the fee shifting

provisions in Title VII and other statutes, such as 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988. is to encourage meritorious litigation by “enabl[ing]

civil rights plaintiffs to employ reasonably competent lawyers

without cost to themselves if they prevail.” Venegas v.

Mitchell 495 U.S. at 86. In the first case construing the fee

provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Court ex

plained that a private plaintiff in a civil rights case acts “as a

•private attorney general.' vindicating a policy that Congress

considered of the highest priority.” Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. at 402. Fee shifting is essential to

this enterprise because.

[ijf successful plaintiffs were routinely forced to bear

their own attorneys’ fees, few aggrieved parties would

be in a position to advance the public interest. . . .

Congress therefore enacted the provision for counsel

fees—not simply to penalize litigants . . . but, more

broadly, to encourage individuals injured by racial

discrimination to seek judicial relief. . . .

Id.

The Court has also construed 42 U.S.C. § 1988 in a number

of cases and has said that “[tjhe standards set forth [under

§ 1988] are generally applicable in all cases in which

Congress has authorized an award of fees to a 'prevailing

party.’ ” Hensley r’. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424, 433 n.7 (1983).

And the objective of § 1988 (and hence of any fee shifting

statute) is to produce “fees which are adequate to attract

competent counsel, but which do not produce windfalls to

attorneys.” Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. at 893-94. In

particular, statutory fees are not intended to liquidate any

private debt that the plaintiff may owe counsel. Venegas v.

Mitchell, 495 U.S. at 90 (Ҥ 1988 controls what the losing

defendant must pay, not what the prevailing plaintiff must

pay his lawyer”).

B. The Tax Problem in Statutory Fee Cases

In fee shifting cases, the trial is concerned solely with the

merits. If the plaintiff wins, due either to a jury verdict or

a bench ruling, the district court later considers an application

for attorneys’ fees from plaintiffs counsel. In fact, the

judgment on fees is so divorced from the merits—so

9

“ancillary”—that the absence of a decision on fees does not

deprive the underlying merits judgment of finality for

purposes of appeal. See White v. New Hampshire Dept, of

Employment Security, 455 U.S. 445 (1982).

There is no dispute that an award of statutory attorneys'

fees is income to counsel and should be taxed accordingly.

The Internal Revenue Service, however, views cases involv

ing statutory fees in the same way it sees ordinary contingent

fee cases, taking the position that all money paid by the

defendant in a statutory fee case, including the fees them

selves, is also income to the plaintiff. Hence the same fees

are taxed as income to both plaintiff and counsel.

If fees were deductible in full for Federal income tax

purposes, their treatment as income would be a moot point.

But they are not. The IRS has successfully argued that fees

should be treated as “miscellaneous itemized deductions,” see

Biehl v. Commissioner. 351 F.3d 982 (9th Cir. 2003), and

under the regular income tax, such deductions are deductible

only to the extent that their total exceeds two percent of

adjusted gross income. 26 U.S.C. § 67. In addition, the

regular income tax imposes a ceiling on miscellaneous

itemized deductions. 26 U.S.C. § 68. Together, these two

provisions serve to increase the nominal marginal tax rate by

five percent (e.g., a marginal rate of 39.6 percent effectively

becomes 41.58 percent). See Laura Sager & Stephen Cohen,

“How the Income Tax Undermines Civil Rights Law,” 73 S.

Cal. L. Rev. 1075. 1084-85 and n.52 (2000).3

3 Professor Cohen has filed an amicus brief here as an academic pro se,

arguing that attorneys’ fees should be considered unreimbursed employee

business expenses under 26 U.S.C. § 62(a)(2)(A). rather than miscel

laneous itemized deductions. Given this characterization, fees would be

excluded from gross income under 26 C.F.R. § 1.62-2(c)(4) (2004).

Professor Cohen proposes a simple and elegant solution to the prob

lems associated with the taxation of attorneys’ fees, and amici endorse

his approach.

10

Even more egregious, the Alternative Minimum Tax

(AMT), which taxpayers must compute and pay if it yields

a higher tax levy than the regular income tax, does not allow

any miscellaneous itemized deductions at all. 26 U.S.C.

.§ 56(b)(l)(A)(i). That means that those prevailing plaintiffs

who are subject to the AMT wall owe taxes equal to either 26

or 28 percent of the court-ordered fee award. 26 U.S.C.

§ 55(b)(l)(A)(i). At a minimum, this will sharply cut into the

recovery on the merits (which is also subject to taxation). See

Sager & Cohen, supra, at 1077-78.

In ordinary contingent fee litigation, the fee can never

be larger than the merits recovery, since counsel’s fee is

computed as a percentage of that amount. But in statutory

fee cases, it is not unusual for a fee award to be larger than

the merits judgment. City o f Riverside v. Rivera. 477 U.S.

561.4 And in cases where the amount of attorneys’ fees

exceeds the plaintiffs recovery, the taxes due on fees

frequently will result in a net financial loss for the plaintiff.

See Adam Liptak. “Tax Bill Exceeds Aw-ard to Officer in

Sex Bias Case,” New York Times (August 11, 2002) at A12

(recounting how a prevailing plaintiff, whose jury verdict

of $3 million had been reduced to $300,000 and whose

lawyers were awarded fees of $850,000, faced a net post-tax

loss of $99,000).

In such cases, the plaintiff is financially worse off prevail

ing than losing. This is also true in cases where injunctive

relief is the primary, or sole, remedy sought, as in a suit

brought to enjoin use of selection devices that are not job-related

but that fall more harshly on African Americans than on whites.

See Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971). In similar

4 The phenomenon of attorneys’ fees exceeding the merits recovery is

especially likely under Title VII and the Americans with Disabilities Act,

where damages are capped at $300,000 for even the largest employers

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 a(b)(3). so larger jury verdicts are routinely

reduced to $300,000.

fashion, there may be no pay loss in a case of sexual

harassment, and the victimized woman may simply want

the security of a judicial prohibition. And even if she also

seeks damages, an injunction may still be the most potent

remedy available against small employers (100 or fewer

employees), where the damage ceiling is $50,000. 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981 a(b)(3). Treating the fees awarded counsel as income

to the plaintiff in such cases, and taxing the plaintiff on that

sum, eviscerates the congressional objective of permitting

plaintiffs ‘To employ . . . lawyers without cost to themselves

if they prevail.” Venegas v. Mitchell, 495 U.S. at 86. Indeed,

such tax treatment would deter citizens from pursuing even

the most meritorious civil rights claims.

C. The Assignment of Income Doctrine Does Not

Apply to Statutory Fees

At the outset of his Summary of Argument, the Solicitor

General makes a number of points that he believes apply to

the ordinary contingent fee setting, but none of them are

pertinent to statutory fees. For example, the Solicitor General

says that “income is to be taxed to the person who earns it.

even when it is paid at that person's direction to someone

else,” Brief for Petitioner at 11; that “when a debt owed by a

taxpayer is satisfied by a direct payment from a third party to

the taxpayer’s creditor, the taxpayer receives ‘income’ in the

amount of the discharged debt,” id.; and that where a taxpayer

“has ‘diverged] the payment from himself to others as the

means of procuring the satisfaction of his wants,' [he] is

subject to tax on the diverted proceeds,” id. Amici do not

quarrel with these tenets, but they do not apply to judicial

awards under a fee shifting statute.

1. The Assignment of Income Doctrine

The principles cited by the Solicitor General represent

differing formulations of the anticipatory assignment of

income doctrine, which the Court developed in the first

12

generation following the adoption of the Federal income tax

to prevent taxpayers from escaping taxation through shell

games. For example, in Lucas v. Earl. 281 U.S. 111 (1930).

the Court declined to bless a scheme in which a taxpayer

assigned 50 percent of his future salary to his wife in an effort

to avoid paying taxes on the entire amount. Id. at 115

(rejecting an “arrangement by which the fruits are attributed

to a different tree from that on which they grew”).

Similarly, in Helvering v. Horst. 31 1 U.S. 112 (1940), the

Court held that the taxpayer was liable for taxes due on

interest from bonds that he held, even though he had clipped

the interest coupons and given them to his son shortly before

the maturity date. And in Horst, the Court noted that it had

previously ruled, in another variation on the assignment of

income theme, that “[i]f the taxpayer procures payment

directly to his creditors of the items of interest or earnings

due him * * * he does not escape taxation because he did not

actually receive the money.” Id. at 116. That is, “[i]f A owes

B a debt, and C pays the debt on A's behalf, it is elementary

that C's payment is income to A as well as to B.” Sinyard v.

Commissioner, 268 F.3d 756, 758 (9th Cir. 2001), cert,

denied. 538 U.S. 904 (2002).

2. The Inapplicability o f the Doctrine to Stat

utory Fees

The principles first enunciated in Lucas v. Earl and

Helvering v. Horst do not apply to the statutory fee context.

A defendant who pays a court-ordered fee aw^ard, for

example, is not discharging a private debt owed by the

plaintiff to counsel, since fees awarded by a court are

divorced from any private understanding between plaintiff

and her lawyer. Thus, even nonprofit organizations that

provide legal services pro bono are entitled to fees if the

plaintiff prevails. Blum v. Stenson. supra (Legal Aid Society

of New York City entitled to fees).

13

In addition, the amount of the fee award has nothing to do

with whatever private agreement plaintiff and counsel may

(or may not) have. See Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. at

93 (“[sjhould a [private] fee agreement provide less than a

reasonable fee . . . the defendant should nevertheless be

required to pay the higher amount. The defendant is not,

however, required to pay the amount called for in a

contingent-fee contract if it is more than a reasonable fee"');

Venegas v. Mitchell, 495 U.S. at 90 (Ҥ 1988 controls what

the losing defendant must pay, not what the prevailing

plaintiff must pay his lawyer”).

Rather than depending on a private arrangement, the tee

award should be a sum “adequate to attract competent

counsel, but which do[es] not produce windfalls to attorneys.”

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. at 893-94. In practice, this means

that the award should be calibrated to reflect the lawyer’s

effort; i.e.. “[t]he most useful starting point for determining

the amount of a reasonable fee is the number of hours

reasonably expended on the litigation multiplied by a

reasonable hourly rate.” Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. at

433. The Solicitor General says that the “ ‘source of the

income’ at issue” is a salient factor in determining who

should be taxed, Brief for Petitioner at 12 (quoting Horst. 311

U.S. at 116), and Hensley makes it clear that the “source” of

the fee award—in particular, its amount— is the lawyer's

effort, not the plaintiffs.

In a statutory fee case, unlike ordinary contingent fee

litigation, two distinct sums are generated. The first is the

judgment on the merits. Then, in a separate proceeding,

attorneys’ fees are awarded by the court. Unlike ordinary

contingent fee litigation, the plaintiff s lawyer has no claim

under fee shifting law's to any portion of the judgment on the

merits. By the same token, Congress did not envision that the

plaintiff herself would retain the attorneys’ fees awarded in

the separate fee proceeding.

14

The difference between private contingent fee arrange

ments and statutory fee shifting is highlighted in pro se cases,

where retained lawyers are absent. If the plaintiff in a

common law tort action decides to represent herself rather

than retain counsel on a contingent basis, and if she then

prevails on the merits, she gets to keep the entire judgment,

including the portion that might otherwise have gone to a

lawyer. But in a case subject to a fee shifting law, a pro se

plaintiff who prevails is entitled only to the merits judgment

and is never eligible for a separate fee award. This is true

even if the pro se plaintiff is a lawyer, since fees are awarded

only to further the congressional goal of attracting retained

counsel. Kay v. Ehrler, 499 U.S. 432.

This is not to suggest that lawyers have a property interest

in fees under lee shifting laws. They do not. Hence the

plaintiff in a statutory fee lawsuit (as in any other case) has

the final say on all substantive matters. This is why the

plaintiff (in the absence of a private agreement with counsel)

is free to bargain away fees in exchange for greater relief on

the merits. See, e.g., Evans v. Jeff 1).. 475 U.S. 717, 731-32

(1986). Jeff D.. however, deals with control of the litigation.

If fees are ultimately awarded, however, they go to counsel;

the plaintiff has no statutory claim on the money. Kay v.

Ehrler, supra.

In Helvering v. Horst, the Court said that “[cjommon

understanding and experience are the touchstones for the

interpretation of the revenue laws.” 311 U.S. at 118. This

sentiment may have been aspirational, but on any “common

understanding,” the plaintiff in a statutory fee case does not

receive income through court-ordered fees.

D. Porter v. AID

Amici believe that only one court has squarely address

ed the issue of the taxability of an award of attorneys’ fees

in the statutory fee context. In Porter v. Director, Agency

15

for International Development, 293 F.Supp.2d 152, the

jury found that the plaintiff had twice been denied promotions

because of retaliation in violation of Title VII, and awarded

a total of $30,000 in damages. In a separate proceeding,

the district court later awarded $253,987 in attorneys’

fees. See No. 00-1954 (D.D.C.), Docket Entry No. 155

(December 12, 2003).

If the IRS’ position prevails and both the damages and fees

awarded in Porter are seen as income to the plaintiff, he

would in all likelihood be subject to the Alternative Minimum

Tax. And since the IRS views fees as “miscellaneous

itemized deductions” which are not deductible under the

AMT (and since the AMT has only two brackets—26 and 28

percent), the plaintiff will owe either 26 or 28 percent of

$283,987 (the total of $253,987 in fees and $30,000 in

damages). That is, he will owe either $73,837 (at 26 percent)

or $79,516 (at 28 percent). But the plaintiff did not receive

any of the fee award; his counsel did. The plaintiff received

only $30,000 in damages, so his net loss will be $43,837 or

$49,516. He would have been much better off financially if

he had lost on the merits at trial. Such pyrrhic victories will

frustrate the congressional goal of encouraging private

citizens to vindicate civil rights.

The district court in Porter was plainly troubled by this

prospect. And given Title VII’s “make whole” imperative, the

court was confident that it possessed authority— il

necessary—to order that the fee award be "grossed up ’ to

ameliorate any adverse tax consequences. 293 F.Supp.2d at

156.5 The district court declined to order grossing up,

5 Other courts have agreed that they have authority under anti-

discrimination statutes to enhance awards to mitigate adverse tax

consequences. See, e.g., Sears v. Atchison, Topeka <fe Santa Fe Ry. Co.,

749 F.2d 1451, 1456 ( 10th Cir. 1984) (Title VII); Jordan v. CCH, Inc., 230

F.Supp.2d 603, 617 (E.D. Pa. 2002) (Age Discrimination in Employment

Act); O'Neill v. Sears Roebuck & Co., 108 F.Supp.2d 443, 446-47 (E.D.

16

however, due to considerations of finality and also because of

a belief that—in the end—the award of attorneys’ fees would

not be deemed income to the plaintiff. Id. Instead, the court

“concluded that the best course is to do what [it] can to ensure

that the attorneys' fee award never becomes a tax problem for

Porter, by . . . explaining the nature of the award clearly, so

that Porter or his tax adviser can refer to the explanation

when preparing income tax returns, and so that the IRS can

consider the explanation before attempting to impose a tax on

Porter for the attorney’s fee award.” Id. at 157.

In its “explanation” for the IRS, the district court said that

“[t]he plaintiff s attorney in a Title VII case performs a public

interest role,” and that Congress authorized fee shifting

“because it recognized that incentives would be needed to

bring lawyers into a controversial field, where recoveries

might not otherwise warrant substantial fees, in order to

vindicate newly enacted civil rights.” Id. The court further

explained that “[a]n award of attorneys’ fees in a Title VII

case is not a percentage, or a subset, or in any way a part of

an award of compensatory damages or of an award of back

pay, front pay, or pre-judgment interest given as equitable

relief.” Id. Rather, “[ijt is a separate award, separately

provided by statute, and made by the court in a separate

proceeding.” Id.

For these reasons, “[t]he ownership issue that appears to

have split the circuits on the taxability of contingent fees . . .

is not germane to a statutory Title VII attorneys’ fee, and

neither is the assignment of income doctrine.” Id. at 158.

That is, “the form of an attorneys’ fee award is that of an

Pa. 2000) (ADEA); EEOC v. Joe's Stone Crab, Inc., 15 F.Supp.2d 1368,

1380 (S.D. Fla. 1998) (Title Vli); Arneson v. Sullivan. 958 F.Supp. 443,

447 (E.D. Mo. 1996) (Rehabilitation Act). See also Blaney v. 1AM,

87 P.3d 757, 761-64 (S.Ct. Wash. 2004) (Washington Law Against

Discrimination). But see Dashnaw v. Pena, 12 F.3d 1112 (D.C.

Cir. 1994).

17

award made to the prevailing party, [but] in substance the

award is to counsel.” Id. (emphasis in original).

Porter is on appeal on the merits, Porter v. Natsios, No.

04-5061 (D.C. Cir.), so the plaintiffs tax liability has not yet

been determined. But the case is instructive in illustrating the

serious tax consequences that can befall a plaintiff who

prevails in a Title VII case, as well as pointing to a way out of

this dilemma. The solution proposed by the district court in

Porter, and advocated in this amicus brief, harmonizes

important tax rules with equally compelling principles of civil

rights law.6

E. The Effect of Statutory Fee Shifting on Banks

The taxpayer in Banks settled his employment case through

an arrangement in which the defendant paid $464,000, of

which $314,000 went to Banks himself and $150,000 to his

lawyer. At the time of settlement, Banks had three viable

claims under three different statutes—Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§1981 and 42 U.S.C. § 1983—and all three were subject to

statutory fee shifting. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (Title VII), and

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (§§ 1981, 1983). It does not matter for tax

purposes if fees are recovered by judicial order or through

settlement.

In any case subject to fee shifting, settlement discussions

invariably include the amount of fees at issue, since this is

part of the defendant’s exposure. Consequently, any

6 As the district court noted in Porter, 293 F.Supp.2d at 154, a

legislative solution would be welcome, but to date none has been

forthcoming. Most recently, the Senate in May 2004 passed S. 1637, the

Jumpstart Our Business Strength (JOBS) bill, which includes a provision

(§ 643) that permits "above the line" deductions of attorneys' fees

awarded or paid in cases involving employment disputes, so that such tees

would not be included in Adjusted Gross Income subject to taxation. The

House bill, H.R. 4520, contains no such provision, and there has been no

conference as of the filing of this brief.

settlement includes—either explicitly or (frequently) implic

itly—a sum devoted to fees. In these circumstances, there

should be no difference in the tax treatment accorded

fees awarded by a court or received by counsel as part of

a settlement.

This Court has repeatedly observed that congressional

policy favors the amicable resolution of Title VII disputes, as

opposed to resolution on the merits following contested

litigation. See Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S.

742. 764 (1998) (noting “Congress’ intention to promote

conciliation rather than litigation in the Title VII context,”

and citing EEOC v. Shell Oil Co., 466 U.S. 54, 77 (1984)).

This pro-settlement policy would be undermined if a Title VII

plaintiff could secure favorable tax treatment of the fees paid

to counsel only by going to trial. See Porter v. AID, 293

F.Supp.2d at 155-56 (if “[c]ivil rights plaintiffs who settle

their claims but are obligated to pay their attorneys fees under

contingency agreements are treated just like other civil

litigants under the assignment of income doctrine . . . such

a result [would be] in direct conflict with the underly

ing purpose of the fee shifting provisions applicable to civil

rights litigation”).

In any event, Congress has shown that it believes that

sums received through settlement should be treated the same

way, for tax purposes, as amounts recovered through

resolution on the merits. See. e.g., 26 U.S.C. § 104(a)(2)

(gross income does not include “the amount of any damages

(other than punitive damages) received (whether by suit or

agreement . . .) on account of personal physical injuries or

physical sickness”) (emphasis added).

It is possible that the amount received by counsel through

settlement of a Title VII (or other statutory fee) claim would

be greater than what a court might award; it also might be

less. But these vagaries are true of all aspects of a settlement,

including the sum recovered by the plaintiff. If in a particular

19

case the IRS believed that the amount received by counsel

through settlement materially exceeded any possible court

award of fees—and if the Service further believed that the

increment should be seen as income to the plaintiff—then the

amount allocated to fees could be challenged. The IRS often

challenges such taxpayer characterizations; indeed, it was

successful in Banks itself in contesting the plaintiff s effort to

characterize his settlement recovery as “personal injury

damages” rather than lost wages. 345 F.3d at 381-82.'

Had the plaintiff in Banks received $314,000 from a jury

verdict, followed by a fee award of $150,000, the fees would

not properly be seen as income to the taxpayer. The tax

treatment is not affected by the fortuity that these amounts

were recovered through settlement.

Amici understand that the taxpayer in Banks did not

advance below the argument made here. The Court may,

however, consider arguments only presented by amici,

Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. at 300; Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S.

643, 646 n.3 (1961), and the judgment of the court of appeals

in Banks can be affirmed on the ground that statutory fees are

not included in the plaintiffs income.

II. ORDINARY CONTINGENT FEES ARE NOT

INCOME TO THE PLAINTIFF

The first issue in this case—whether fees received by

counsel represent income to the plaintiff in statutory fee

cases—is not a close question. They do not. The result is the

same for the remaining issue—whether fees received by 7

7 Any IRS challenge to the amount allocated to attorneys’ fees in a Title VII

settlement would make sense only in a tax regime in which (1) tees received by

counsel under fee shifting statutes are not deemed income to the plaintiff but (2)

fees received by counsel in ordinary contingent fee litigation are treated as the

plaintiffs income. As is shown below, however, fees received by counsel in

ordinary contingent fee cases should not be considered income to the plaintiff,

albeit for different reasons than in the statutory fee context.

20

counsel in ordinary contingent fee litigation should be

deemed the plaintiffs income—although the analysis differs.

Attorneys’ fees are not income to the plaintiff in either

situation.

A. The Split in the Circuits

The courts of appeals have divided over the treatment of

counsel fees in the ordinary, non-fee shifting context. Five

circuits agree with the IRS and see fees as income to the

plaintiff, on an assignment of income rationale. Raymond v.

United States, 355 F.3d 107 (2d Cir. 2004), petition for cert,

pending, No. 03-1415; Young v. Commissioner, 240 F.3d 369.

376-79 (4th Cir. 2001); Kenseth v. Commissioner, 259 F.3d

881 (7th Cir. 2001); Hukkanen-Campbell v. Commissioner,

274 F.3d 1312 (10th Cir. 2001), cert, denied, 535 U.S. 1056

(2002); Baylin v. United States, 43 F.3d 1451, 1454-55 (Fed.

Cir. 1995).

Three other circuits have rejected the IRS position and

have held that the portion of a judgment due counsel as a

contingent fee is not income to the plaintiff. Cotnam v.

Commissioner, supra: Srivastava v. Commissioner, 220 F.3d

353. 364-65 (5th Cir. 2000); Estate o f Clarks v. United States,

202 F.3d 854 (6th Cir. 2000); Banks, supra (6th Cir. 2003);

Davis v. Commissioner, 210 F.3d 1346 (11th Cir. 2000) (per

curiam): Foster v. United States, 249 F.3d 1275, 1279-80

(1 1th Cir. 2001). The Fifth and Eleventh Circuit stress that

counsel was entitled under state law to an ironclad lien on his

share of the proceeds, while the Sixth has moved from a

primary focus on state lien law in Estate o f Clarks to a more

universal approach in Banks that likens the contingent fee

arrangement to a joint venture in which the lawyer has a

percentage interest.

The Ninth Circuit has conflicting decisions, depending in

part on its reading of lien law in different states. Compare

Banaitis, supra (9th Cir. 2003) (fees received by counsel are

not income to the plaintiff), with cases reaching the opposite

result: Benci-Woodward v. Commissioner, 219 F.3d 941, 944

(9th Cir. 2000), cert, denied, 531 U.S. 1112 (2001); Coady v.

Commissioner, 213 F.3d 1187 (9th Cir. 2000). cert, denied.

532 U.S. 972 (2001); Sinyard v. Commissioner, supra.

B. The Dispositive Nature of the Joint Venture

Analogy

As noted. Banks analogized a contingent fee agreement to a

joint venture. A joint venture is a type of partnership for tax

purposes, 26 U.S.C. § 761(a), and partners realize income

only on their “[distributive share of partnership gross

income.” 26 U.S.C. § 61 (a)(13); see 26 U.S.C. § 702. Hence,

if a contingent fee arrangement is seen as akin to a joint

venture, the plaintiff will realize income only on her share of

the court award (or settlement); in particular, fees received by

counsel w ill not be deemed income to the plaintiff.

Also in Banks, the court eschewed reliance on state lien

law, saying that, “[gjiven the various distinctions among

attorney’s lien laws among the fifty states . . . a ‘state-by-

state’ approach would not provide reliable precedent . . . or

provide sufficient notice to taxpayers as to [the) tax treatment

of contingency-based attorneys fees paid from their respect-

tive jury awards.” 345 F.3d at 385. Under a global approach,

the issue is whether an ordinary contingent fee relationship is

more like an assignment of income or a joint venture. It the

former, the lawyer’s share is properly treated as income to the

plaintiff. But if the relationship is more like a joint venture,

the share received by counsel is only counsel's income—not

the plaintiffs. In fact, the essential attributes of a joint

venture are present in the contingent fee relationship. 8

8 If it is thought preferable to address the tax consequences of

contingent fee agreements on a “state-by-state” basis, amici believe that

the Ninth Circuit in Banaitis properly analyzed the tax treatment that

flows from Oregon lien law.

22

1. Kensetli

Judge Posner’s opinion in Kenseth, supra, is the best

articulation of the assignment of income perspective on

contingent fee agreements, so the decision warrants careful

examination. Kenseth first describes the tax problem faced

by the taxpayer, which was aggravated but not entirely caused

by the AMT. 259 F.3d at 882. The decision then notes that

”[t]he circuits are split on whether a contingent fee is, as the

Tax Court held in this case, a part of the client's taxable

income,” id. at 883 The opinion agreed with the Tax Court,

id., reasoning that a contingent-fee lawyer’s share of a

recovery should be seen as a business expense for the

plaintiff. Id. It is simply unfortunate if the tax code does not

permit lull (or any) deduction of this expense. Id.9

9 Judge Posner notes at the outset of Kenseth that the taxpayer’s

underlying case dealt with age discrimination. 259 F.3d at 882. The Age

Discrimination in Employment Act provides for statutory attorneys’ fees,

see 29 U.S.C. § 626(b) (incorporating among other things the fee shifting

provisions in 29 U.S.C. § 216(b)), but Kenseth does not address the

singularities of statutory fee litigation and instead assumes that it is

dealing with an ordinary contingent fee case.

Only three of the other circuit decisions cited above arose under laws

permitting fee shifting—Banks itself, Hukkanen-Campbell (Title VII), and

Sinyard (ADEA). As in Batiks (and Kenseth). the Tenth Circuit in

Hukkanen-Campbell did not acknowledge that statutory fees were in the

picture. The Ninth Circuit in Sinyard undertook a cursory examination of

this issue. After saying that, “[i]f A owes B a debt, and C pays the debt

on A's behalf, it is elementary that C's payment is income to A as well as

to B,” 268 F.3d at 758, the majority simply observed that fee awards are

formally bestowed on the plaintiff, not counsel, id. at 759, citing Evans v.

JeffD. and Venegas v. Mitchell. As the dissent noted, though, JeffD. and

Venegas “were decided in a different context—namely, client control over

the resolution of a case.’’ Id. at 761 n.2. The dissent properly concluded

that, “[h]ere, defendant C does not satisfy a debt on behalf of plaintiff A;

rather, C satisfies its own statutory obligation, imposed by the ADEA.”

Id. at 762.

23

In Kenseth, the taxpayer’s underlying claim arose in

Wisconsin and, relying on Wisconsin lien law, he argued that

the lawyer was a co-owner of the underlying claim. Were

that true, the lawyer’s share of a recovery would merely he

her entitlement as co-owner; it would not be the plaintiff’s

business expense. But Kenseth quickly disposed oi any

argument about co-ownership grounded on Wisconsin lien

law. Id. at 884.

In the end, Kenseth concluded that “what [the taxpayer]

really is asking us to do is to assign a portion of his income to

the law firm.” Id. (emphasis in original). And that does not

work: “an assignment of income . . . by a taxpayer is

ineffective to shift his tax liability.” h i. citing Lucas v. Earl.

281 U.S. at 114-15.

2. The Economic Realities

The Solicitor General, who addresses only the ordinary

contingent fee situation, acknowledges that the ultimate tax

question is one of reasonableness—whether it is “reasonable

to treat the entire award[] as gross income” to the plaintiff.

Brief for Petitioner at 13. Reasonableness, in turn, is a

function of the practical realities oi a situation. And despite

its holding, Kenseth helps to reveal the economic reality that

a contingent fee arrangement is a joint venture tor tax

purposes. As the decision rightly says, though, this has

nothing to do with state lien law.

Rather, as Judge Posner acknowledged in Kenseth. “there

is a sense in which contingent compensation constitutes

the recipient a kind of joint venturer of the payor.” 259 F.3d

at 883. lie elaborated on this point in his book, Economic

Analysis o f Law, saying a contingent fee agreement is a

“situation of joint ownership,” because "a contingent fee

contract makes the lawyer in effect a cotenant of the property

represented by the plaintiffs claim.” Id. at 625 (parentheses

omitted).

24

Consider a tract of land which, undeveloped, has a low'

value. The owner of the land enters into an agreement with a

developer, in which the developer agrees to improve the land

by putting in roads and a sewage system and building houses,

and in which the parties agree to apportion income from the

developed land on a 60-40 basis, with the developer entitled

to 40 percent. In this joint venture, the parties (the land

owner and the developer) realize income only on their

respective “distributive share[s]” of the gross income from

the developed land. See 26 U.S.C. §§ 61(a)(13), 761(a).

Now, assume that a salesperson is hired to sell the houses

on a commission basis, i.e., a percentage of the sales price of

each house. As Kenseth correctly says, “the sales income [the

salesperson] generates is income to the [owner/developer]

and his commissions are a deductible expense, even though

they were contingent on his making sales.” 259 F.3d at 883.

The examples of the developer and salesperson show' that a

contingent compensation arrangement, by itself, is insuf

ficient to indicate whether the compensation received is

properly considered a business expense of the owner—and

hence part of the owner’s income. But if the contingent

nature of compensation does not explain the difference in tax

treatment as between the developer and the salesperson, then

what is the explanation? The Sixth Circuit in Banks,

harkening back to the language of Lucas v. Earl and

Helvering v. Horst, says that—with respect to the devel

oper—the landowner “transferred some of the trees from the

orchard, rather than simply transferring some of the orchard’s

fruit.” 345 F.3dat386.

The metaphor used in Banks is not particularly illumi

nating. Instead, one salient difference between the developer

and the salesperson is that the developer took significant steps

to enhance the value of the property. In contrast, the

salesperson simply sold pieces of the land; he did nothing to

increase its value. The developer creates wealth; the sales

person does not.

3. The Contingent Fee Lawyer as Joint Venturer

A contingent fee lawyer is like the developer in the

examples above. The lawyer’s task is to enhance the value of

property—to take an undeveloped claim and to improve it. so

that a jury will place a fully compensatory value on it.

Of course, a landowner can hire a developer at a fixed rate

and finance the development himself, rather than entering

into a joint venture agreement. If so, the compensation paid

to the developer is properly seen as a business expense of the

owner. But if for economic reasons—e.g., a lack of money to

finance development—the owner elects to make the

developer a joint venturer, then the developer assumes part of

the risk. And if this happens, the compensation ultimately

received by the developer (assuming the enterprise is

successful) is not the landowner’s business expense. Under

the Tax Code, it is income solely to the developer. 26 U.S.C.

§ 61 (a)( 13).

In the same way, the holder of a legal claim may retain a

lawyer on an hourly basis. If this occurs, the compensation

received by the lawyer is properly seen as the claimholder’s

expense. But if the claimholder lacks the money to finance

litigation and desires to share the risk, she may enter into a

contingent fee agreement with counsel. If so, the compen

sation ultimately received by counsel (if the lawsuit is

successful) is not the claimholder’s business expense and is

income solely to counsel.

A developer retained at a fixed rate, like a lawyer retained

on an hourly basis, may engage in wealth creation by

improving property. But only the developer as joint venturer,

and the contingent fee lawyer, both (1) create wealth, and (2)

assume risk. One who both enhances the value of property,

and who assumes the risk that the property may not be

25

26

profitable, is in the same economic position as the owner of

the property, whether or not a formal co-tenancy relationship

exists. Tax law should recognize the economic reality that a

lawyer retained on a contingent basis is “in effect a cotenant

of the property represented by the plaintiffs claim.”

Economic Analysis o f Law, supra, at 625.10

On the one hand, a contingent fee agreement shares the

essential attributes of a joint venture—wealth creation and

assumption of risk. On the other, there are important

differences between contingent fee arrangements and the

devices that have been seen as mere assignments of income.

For example, contingent fee agreements are animated not by

tax avoidance purpose but rather by economic motive. See

Economic Analysis o f Law at 624. And application of the

assignment of income doctrine to the contingent fee setting

results in double taxation; i.e., counsel's fee is treated as

income to both counsel and the plaintiff. Double taxation is

not unprecedented, but it is inefficient economically and

should not be indulged without the type of clear signal from

Congress that is lacking here. See Banks, 345 F.3d at 385-86.

Ordinary contingent fee agreements are much closer to

joint ventures than to the schemes interdicted by the

assignment of income doctrine. Attorneys’ fees received

by contingent fee counsel should not be treated as income to

the plaintiff.

10 Kenseth notes that fees paid to a lawyer retained on an hourly basis

are treated as the plaintiff s expense and says, “[w]e cannot see what

difference” a contingent fee arrangement makes. 259 F.3d at 883. The

difference is counsel’s assumption of risk, which leads to a fundamental

lack of symmetry: the hourly lawyer is entitled to payment for his services

even if he loses. But if the contingent fee lawyer loses, she is not entitled

to payment, and she cannot take a business loss deduction in connection

with her unreimbursed services.

CONCLUSION

A judicial award of attorneys’ fees under a fee shifting

statute is manifestly not income to. the plaintiff. The same is

true of fees recovered as part of a settlement of a claim

subject to fee shifting. The judgment of the Sixth Circuit in

Banks can be affirmed on this ground alone.

In addition, fees received by counsel in all contingent fee

cases, even those that do not arise under fee shifting statutes,

should not be deemed income to the plaintiff, either, because

contingent fee agreements are materially the same as joint

ventures. The judgments in both Banks and Banaitis can be

affirmed on this ground.

The judgments of the courts of appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted.

Douglas B. Huron *

Stephen Z. C her i kof

Heller, Huron , Chertkof

Lerner, Simon & Salzman

1730 M Street, NW, Suite 412

Washington, DC 20036

(202)293-8090

* Counsel of Record Attorneys for Amici. Curiae

Angela Dalfen

N ational Employment

Lawyers A ssociation

44 Montgomery Street, Suite 2080

San Francisco, CA 94104

(215) 296-7629

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

The National Employment Lawyers Association (NELA) is

the only professional membership organization in the country

comprised of lawyers who represent employees in labor,

employment and civil rights disputes. NELA and its 67 state

and local affiliates have a membership of over 3,000

attorneys who are committed to working on behalf of those

who have been victims of wrongful termination and unlawful

employment discrimination. NELA strives to protect the

rights of its members’ clients, and regularly supports prece

dent-setting litigation affecting the rights of individuals in the

workplace. NELA’s members represent clients under all the

fee shifting statutes set forth in the Statement of Interest.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(“LDF”) is a non-profit corporation established under the

laws of the State of New York. It was formed to assist black

persons in securing their constitutional and statutory rights

through the prosecution of lawsuits and to provide legal

services to black persons suffering injustice by reason of

racial discrimination. For six decades LDF attorneys have

represented parties in litigation before this Court and the

lower federal courts involving race discrimination, specifi

cally including race discrimination in employment. See, e.g..

Griggs i’. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Franks v. Bowman

Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976); Bazemore v. Friday, 478

U.S. 385 (1986); Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337

(1997). LDF also represented the successful plaintiff in the

case that established the basic standard for awarding fees

under federal fee-shifting statutes, Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968), and it has frequently

appeared before this Court as amicus curiae in matters

involving the construction of federal civil rights laws.

AARP is a nonpartisan, nonprofit membership organization

of more than 35 million people aged 50 or older dedicated to

2 a

addressing the needs and interests of older Americans. AARP

supports and defends the rights of older Americans and the

laws and public policies designed to protect them.

Approximately one half of AARP's members remain active in

the work force and are protected by one or more federal fee-

shifting statutes, including, inter alia, the Age Discrimination

in Employment Act, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Moreover, other

types of litigation that involve contingent fee arrangements,

including that conducted pursuant to federal and state

consumer protection statutes, can be an effective mechanism

to enforce the rights of older Americans involving a broad

range of issues. Treating attorneys’ fees, whether awarded

under fee-shifting statutes or obtained pursuant to a contin

gency agreement, as taxable income to prevailing plaintiffs

would be counterproductive to the remedial purposes of

litigation. Additionally, contrary to the interests of the parties,

such tax treatment would act as a disincentive to settlements

and. consequently, unnecessarily burden court systems.

AARP. therefore, opposes treating attorneys’ fees as taxable

income to prevailing plaintiffs and urges the Court to affirm

the decisions below.

Trial Lawyers for Public Justice (TLPJ) is a national public

interest law firm dedicated to using trial lawyers’ skills and

approaches to create a more just society. Through precedent

setting litigation, TLPJ prosecutes cases throughout the

country designed to enhance consumer and victims’ rights,

environmental protection, civil rights and liberties, workers’

rights, America’s civil justice system, and the protection of

the poor and powerless. TLPJ is committed to preserving an

accessible system of justice in this country and appears as

amicus curiae in this case because the treatment of attorneys’

fees as taxable income to the client could further diminish

access to the courts for those who need legal representation to

enforce their rights but who cannot afford to pay competent

counsel on their own.

Public Advocates, Inc., one of the oldest public interest law

firms in the nation, was founded in 1971 to challenge the

persistent, underlying causes and effects of poverty and

discrimination and to work for the empowerment of the poor

and people of color by raising a voice for social justice in

government, corporate and other institutions. Public

Advocates was instrumental in the recognition ol the “private

attorney general” doctrine in Serrano v. Priest, 20 Cal.3d 25

(1977), and statutory attorneys’ fees continue to play an

important role in enabling Public Advocates to represent poor

communities and individuals today.

The Western Center on Law and Poverty is the oldest and

largest state support center for California’s legal services

program serving the poor. The Western Center, which no

longer receives federal funding, depends on court-awarded

statutory attorneys’ fees. In most of the Center’s cases, the

clients do not receive a monetary reward. The possibility that

the Center's indigent clients nonetheless could owe

substantial sums of money in taxes would certainly deter

litigation on their behalf.