Legend for Map of House District 36

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legend for Map of House District 36, 1982. 29f753ca-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9b870466-b424-40bd-b52e-42024a4d1c7f/legend-for-map-of-house-district-36. Accessed January 31, 2026.

Copied!

LEGEND FOR MAP OF HOUSE DISTRICT 35

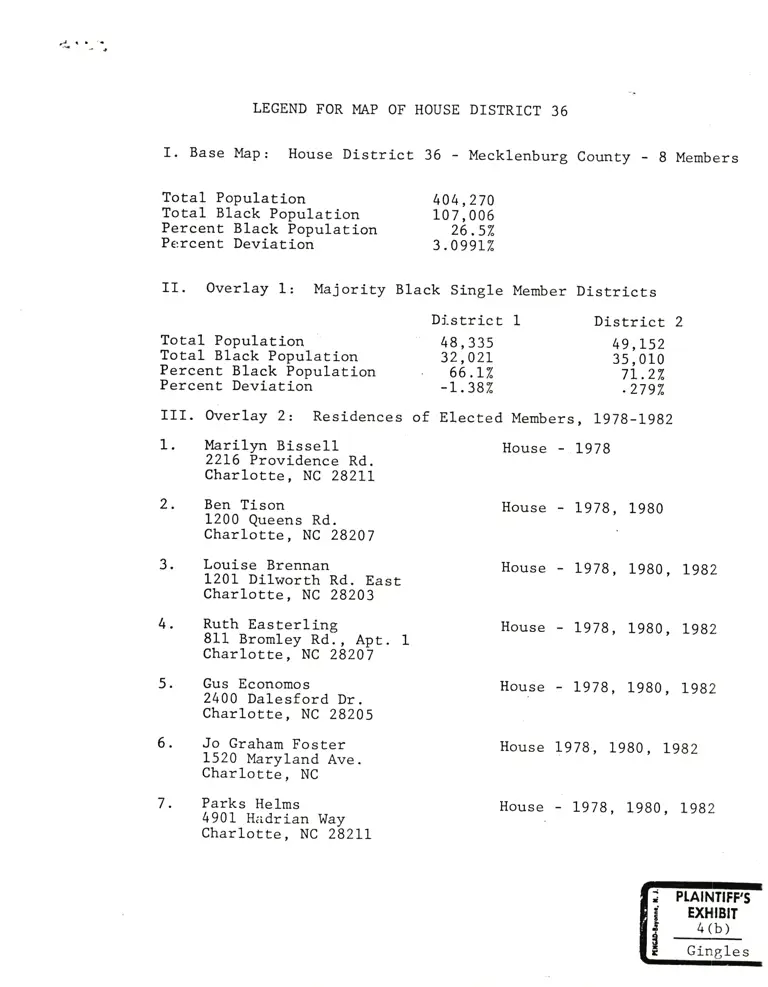

r. Base Map, House District 36 - Mecklenburg county - g Members

II. Overlay L: Majority Black Single

Total Population

Total BLack Population

Percent Black Population

Pe:rcent Deviation

TotaL Population

Total Black Population

Percent BLack Population

Percent Deviation

III. Overlay 2z Residences

L. Marilyn Bissell

22L6 Providence Rd.

Charlotte, NC 282LL

2. Ben Tison

1200 Queens Rd.

Charlotte, NC 28201

3. Louise Brennan

L20L Dilworrh Rd. Easr

Charlotte, NC 28203

4. Ruth Easterling

811 Bromley Rd., Apr. 1

Charlotte, NC 28207

5. Gus Economos

2400 Dalesford Dr.

Charlotte, NC 28205

6. Jo Graham Foster

L520 Maryland Ave.

Charlotte, NC

7 . Parks Helms

4901 H;idrian I{ay

Charlotte, NC 282LL

Member Districts

1 District 2

49,L52

35,0L0

7L.22

.2797"

Members, L978-L982

House - L978

House - L978, L980

House - L978, 1980, L98Z

House - L978, L980 , LgBz

House - L978, 1980 , L9B2

House L978, 1980, L982

House - L978, 1980 , L982

404,270

107,006

26 .57"

3.099t7"

Di-strict

49,335

32,02L. 66.L2

-1.382

of Elected

d

tt

i

E

P[AINTIFF'S

EXHIBIT

4(b)

Gingles

8. lqf^Spoon House - Lg7B, 1980, Lggz

7028 Folger Dr.

Charlotte, NC 282LL

g. Jim Black House - 1980 , Lg82

417 Lynderhill Lane

Matthews, NC 28286

10. Phil Berry House - LgBz

3709 Cobbl.eridge Rd

Charlotte, NC