Whitus v. Balkcom Opinion

Public Court Documents

June 18, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Whitus v. Balkcom Opinion, 1964. 9c8d0e11-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9c7097eb-ab6f-44d2-9cc1-08077c4043bd/whitus-v-balkcom-opinion. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

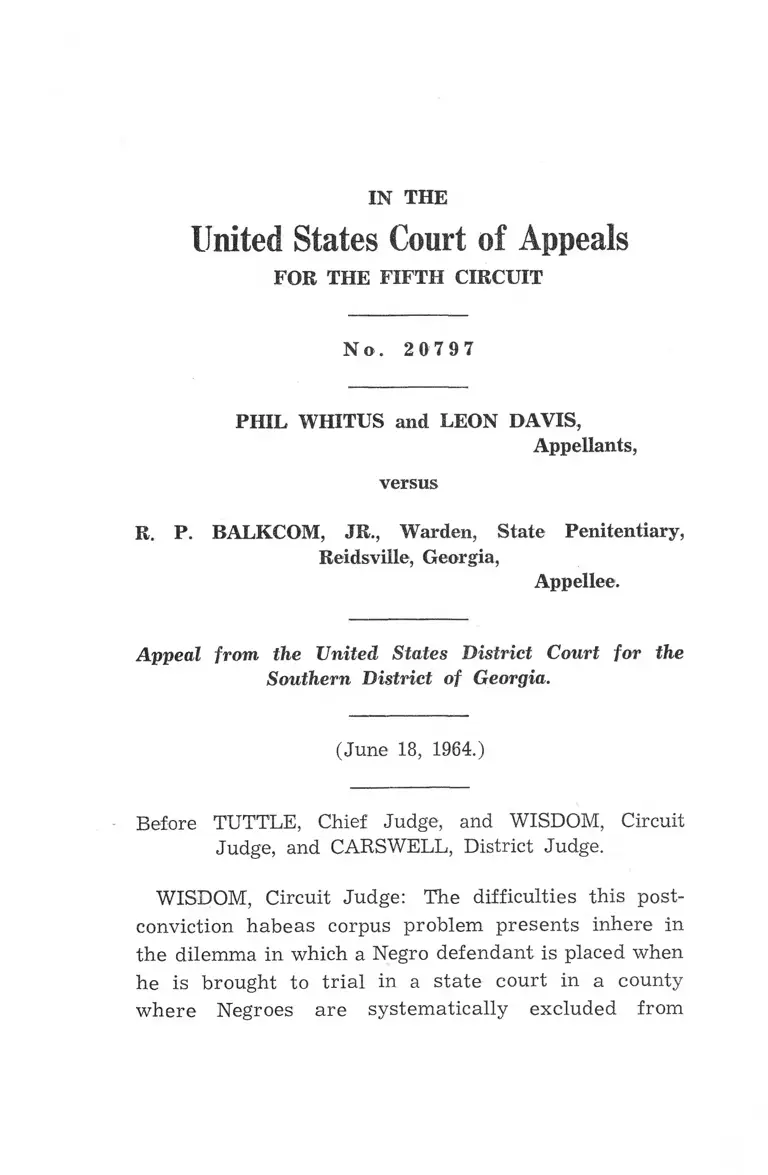

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 2 0 7 9 7

PHIL WHITUS and LEON DAVIS,

Appellants,

R. P.

versus

BALKCOM, JR., Warden, State Penitentiary,

Reidsville, Georgia,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Georgia.

(June 18, 1964.)

Before TUTTLE, Chief Judge, and WISDOM, Circuit

Judge, and CARSWELL, District Judge.

WISDOM, Circuit Judge: The difficulties this post

conviction habeas corpus problem presents inhere in

the dilemma in which a Negro defendant is placed when

he is brought to trial in a state court in a county

where Negroes are systematically excluded from

2 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

juries.1 The matrix within which this problem de

veloped is the social structure of the deep South.

The two Negro petitioners were tried in the Superior

Court of Mitchell County, Georgia, for the murder of

a white farmer. They were convicted and sentenced

to die. Mitchell County is a small county in rural

Georgia.2 No Negro has ever served on a grand jury

or on a petit jury in Mitchell County. The attorneys

for the petitioners were fully aware of this fact. They

were also fully aware of the hostility that an attack

on the all-white jury system would generate in a

community already stirred up over the killing. Without

consulting the defendants, the attorneys decided not

to object, ili the trial or on appeal, to the systematic

exclusion of Negroes from either jury. Later, in this

habeas corpus proceeding, the federal district court

held that the attorneys’ non-assertion in the state

court of a timely objection to the composition of the

juries was an effectual waiver of that objection.

1 See Sofaer, Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners:

The Isolation Principle, 39 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 78 (1964); Reitz, Federal

Habeas Corpus: Impact of an Abortive State proceeding, 74

Harv. L. Rev. 1315, 1324-32 (1961); Hart, Foreword: The Time

Chart of the Justices, 73 Harv. L, Rev. 84, 103-108 (1959);

Brennan, Federal Habeas Corpus and State Prisoners: An Exer

cise in Federalism, 7 Utah L. Rev. 423 (1961); Bator, Finality

in Criminal Law and Federal Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners,

76 Harv. L. Rev. 441 (1963); Schaeffer, Federalism and State

Criminal Procedure, 70 Harv. L. Rev. (1956); See especially

Comment, Negro Defendants and Southern Lawyers: Review in

Federal Habeas Corpus of Systematic Exclusion of Negroes

from Juries, 72 Yale L. Jour. 559 (1963); Note, Lightfoot, Waiver

of Right to be Tried Before Jury from which Members of One’s

Race have not been Systematically Excluded, 16 Ala. L, Rev.

117 (1963). See also Note, Racial Discrimination, Systematic

Exclusion in Jury Selection, 24 La. L. Rev. 393 (1964).

2 The population of Mitchell County, according to the 1960

census is about 20,000, 9,000 Negroes and 11,000 white persons.

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 3

Many constitutional rights may be waived. And, in

the interests of legal economy and the integrity of

orderly procedure in state courts, a defendant’s non

assertion of certain constitutional rights before a trial

or in the early stages of a trial has been treated as a

“waiver” of those rights. This handy rule applies, for

example, to the right to be tried by a jury or the right

to counsel. It does not fit this case.3

The core of this case is the lack of remedy in the

state courts. The petitioners and their attorneys had

no desire to give up their right to be tried by a jury

chosen without regard to the race of the jurors. It

was not to their interest to do so—except as a choice

of evils. A choice of evils was indeed the only state

remedy open to them. The petitioners could choose

to be prejudiced by the hostility an attack on the all-

white jury system would stir up. Or they could choose

to be prejudiced by being deprived of a trial by a jury

of their peers selected impartially from a cross-section

of the community. This is the “grisly” ,4 hard, Hobson’s

8 “ The rights which a defendant may waive are those which

establish procedures designed to insure fairness, but which a

particular defendant may deem it advantageous to forego. The

clearest example, perhaps, is the right to jury trial, which

many defendants waive in the expectation that trial by a judge

alone will be beneficial to their cause. . . . If Johnson v. Zerbst

permits a defendant to forego some of the constitutional safe

guards if he deems it to his advantage to do so. The law re

spects his choice in the first instance and holds him to it if he

should later change his mind. These considerations are not rele

vant when the defendant ‘waives’ an opportunity to protest un

constitutional action, in the sense that a violation of a state rule

of procedure forecloses some part of the review otherwise avail

able in the state judicial system. If a forfeiture of constitutional

rights is to be made the outcome of this kind of lapse, it must

be explained on some basis other than an interest in allowing a

defendant to follow what seems to him his most advantageous

course of action.” Reitz, Federal Habeas Corpus: Impact of an

4 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

choice the State puts to Negro defendants when it

systematically excludes Negroes from juries; white

defendants are not subjected to this burden.

The constitutional vice is not just the exclusion of

Negroes from juries.* 4 5 It is also the State’s requiring

Negro defendants to choose between an unfairly con

stituted jury and a prejudiced jury. We hold that this

discrimination violates both the equal protection and

the due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.6

I.

Oversimplifying the facts, the homicide occurred

November 15, 1959, when Leon Davis, one of the peti

tioners, killed a respected white farmer after an

altercation between the two precipitated by each caus

ing his automobile to bump into the other’s automobile.

Phil Whitus and two other Negroes were in Davis’s

automobile and were at the scene of the killing. All

Abortive State Proceeding, 74 Harv. L. Rev. 1266, 1333, 1336

(1961).

4 This is the term Mr. Justice Brennan used in Fay v. Noia,

372 U. S. 391, 440, to describe Noia’s predicament.

5 The exclusion of Negroes from petit juries trying Negro

defendants has been repeatedly held to violate the equal pro

tection clause as well as the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Reece v. State of Georgia, 1955, 350 U. S. 85,

76 S. Ct. 167, 100 L. Ed. 17; Patton v. State of Mississippi, 1947,

332 U. S. 463, 68 S. Ct. 184, 92 L. Ed. 76: Norris v. State of

Alabama, 1935, 294 U. S. 587, 55 S. Ct. 579, 79 L. Ed, 1074;

Carter v. State of Texas, 1900, 177 U.S. 442, 20 S.Ct. 687, 44 L.

Ed. 839; United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Ha.rpole, 5 Cir. 1959,

263 F. 2d 71, cert, den’d 1959, 361 U.S. 838, 80 S. Ct. 58, 4 L. Ed.

2d 78.

0 We have based our decision on Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391.

At the same time, we have considered, as Mr. Justice Harlan

would require the Court to consider, “ the adequacy, or fairness,

of the state ground” .

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 5

four were indicted for murder. The attorneys for the

defendants decided against requesting a change of

venue.7 January 13, 1960, the jury found Davis and

Whitus guilty as charged.8 Under Georgia law, since

the jury withheld a recommendation of mercy, the

verdict carried the sentence of death by electrocution.

The petitioners filed unsuccessful motions for new

trials, appeals to the Supreme Court of Georgia, and

petitions for certiorari to the United States Supreme

Court.9 Davis contended that the trial court erred in

admitting in evidence an allegedly coerced confession

and in making an erroneous charge to the jury on

insanity. Whitus contended that he did not participate

in the killing in any way; that there was no conspiracy

to commit any crime; and that whatever assistance he

gave to Davis he gave unwillingly at the point of

Davis’s gun. In the state court proceedings petitioners

did not refer to the composition of the juries, except

for a vague allusion in the petition for certiorari to

the United States Supreme Court.

The attorneys first presented the issue now before

this Court in a petition for habeas corpus in the United

States District Court. That court denied the petition

7 Mr. Walter Jones, attorney for Whitus, testified that he “had

a conference with the other attorneys in the case and we agreed

that [if a request for a change were made and acted on favor

ably] the trial judge might change it to Baker County and we

were better off in Mitchell.”

8 The two other defendants pleaded guilty and were sentenced

to life imprisonment. One was sixteen years of age. The other

testified for the State.

9 Whitus v. State, 1960, 216 Ga. 284, 116 S.E,2d 205; cert,

den’d 1961, 365 U. S. 831, 81 S. Ct. 718, 5 L. Ed. 2d 708; Davis

v. State, 1960, 216 Ga. 110, 114 S.E.2d 877.

6 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

on the ground, among others, that a state remedy

through habeas corpus was still available. We affirmed.

Whitus v. Balkcom, 5 Cir. 1962, 299 F.2d 844. The

Supreme Court, per curiam, vacated the judgment and

remanded the case. Whitus v. Balkcom, 1962, 370 U. S.

728, 82 S. Ct. 1575, 8 L. Ed. 2d 803. Again the district

court dismissed the petition.10 The petitioners are

before us on their appeal from that order of dismissal.

The factual question of the existence of the custom

of systematic exclusion of Negroes from the Mitchell

County juries is not at issue. The appellee relies

solely on the doctrine of waiver. The appellee’s brief

states: “Rather than argue the substantive issue of

systematic exclusion of Negroes from the juries of

Mitchell County and thereby attempt to overcome this

Court’s decision in United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman,

5 Cir. 1962, 304 F.2d 53, cert, den’d, 1963, 372 U. S. 924,

83 S. Ct. 741, 9 L. Ed. 2d 729, appellee will admit for

the purposes of this Appeal that the present case is

adversely covered by such decision.”11

10 The district court held: (1) the evidence was sufficient

to support the conviction; (2) there was no evidence to support

the contention that there was discrimination in the selection of

the jury; (3) there was no violation of the petitioner’s right to

equal protection or due process.

11 The district court found that there was a complete revision

of the jury list two months before the commission of the crime,

and the names of thirty Negroes were in the jury box at the

time of the trial. The testimony, however, showed that no

Negro had ever served on either the grand jury or the petit

jury. The jury lists were based on the names on the County

tax returns. These returns were on yellow sheets for the Negroes

and white sheets for the whites. See Avery v. Georgia, 1953,

345 U. S. 559, 73 S.Ct. 891, 97 L.Ed. 1244. See also Collins v.

Walker, 5 Cir. 1964, 329 F.2d 100.

Whitus, et al. v. Balk.com, Jr. 7

II.

The classic, Johnson v. Zerbst definition of waiver

is “an intentional relinquishment or abandonment of

a known right or privilege” .12 The general principles

governing “waiver” of constitutional rights, as that

doctrine is applied in federal habeas corpus post-con

viction proceedings, are succinctly stated in Mr. Justice

Frankfurter’s separate opinion in Brown v. Allen, 1953,

344 U. S. 443, 503, 73 S. Ct. 397, 97 L. Ed. 469:

“Of course, nothing we have said suggests

that the federal habeas corpus jurisdiction can

displace a State’s procedural rule requiring that

certain errors be raised on appeal. Normally

rights under the Federal Constitution may be

waived at the trial, and may likewise be

waived by failure to assert such errors on

appeal. When a State insists that a defendant

be held to his choice of trial strategy and not

be allowed to try a different tack on State

habeas corpus, he may be deemed to have

waived his claim and thus have no right to

assert on federal habeas corpus. Such con

siderations of orderly appellate procedure give

rise to the conventional statement that habeas

corpus should not do service for an appeal.

However, this does not touch one of those

extraordinary cases in which a substantial

claim goes to the very foundation of a proceed

ing.” (Citations omitted. Emphasis added.)

12 Johnson v. Zerbst, 1938, 304 U. S. 458, 464, 58 S. Ct. 1019,

82 L. Ed. 1461.

8 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

The Supreme Court has recently expressed itself on

the subject of waiver in Fay v. Noia, 1963, 372 U. S. 391,

83 S. Ct. 822, 9 L. Ed. 2d 837, a case pertinent here

on the facts. The Court said:

“If a habeas applicant, after consultation with

competent counsel or otherwise, understand-

ingly and knowingly forewent the privilege of

seeking to vindicate his federal claims in the

state courts, whether for strategic, tactical, or

any other reasons that can fairly be described

as the deliberate by-passing of state pro

cedures, then it is open to the federal court

on habeas to deny him all relief. . . . At

all events we wish it clearly understood that

the standard here put forth depends on the

considered choice of the petitioner. Cj. Carnley

v. Cochran, 369 U. S. 506, 513-517; Moore v.

Michigan, 355 U. S. 155, 162-165. A choice made

by counsel not participated in by the petitioner

does not automatically bar relief. Nor does a

state court’s finding of waiver bar independent

determination of the question by the federal

courts on habeas, for waiver affecting federal

rights is a federal question. E.g., Rice v.

Olson, 324 U.S. 786.” (Emphasis added.)

In addition to its holding on waiver,18 Fay v. Noia

makes it clear that to invoke the Great Writ a peti- 13 *

13 See Daniels v. Allen, 1953, 344 U. S. 482, 73 S.Ct. 420, 97

L.Ed. 502. “ Clarity of anaylsis requires that each device be

treated as an isolated doctrine, though such treatment is es

sentially artificial. If exhaustion is interpreted to include

presently unavailable remedies, it would appear that the waiver

and adequate-state-ground rules are merely semantic variants of

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 9

tioner need exhaust only the state remedies available

to him at the time he files his petition. As to the

applicability of the doctrine of “an adequate and in

dependent state ground” , the Court said:

“ [T]he doctrine under which state procedural

defaults are held to constitute an adequate

and independent state law ground barring

direct Supreme Court review is not to be ex

tended to limit the power granted the federal

courts under the federal habeas statute,” 372

U.S. at 399.

Two recent decisions of this Court deal with waiver

in systematic exclusion cases: United States ex rel.

Goldsby v. Harpole, 5 Cir. 1959, 263 F.2d 71, cert, den’d

1959, 361 U.S. 838, 80 S. Ct. 58, 4 L, Ed. 2d 78 and United

States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 5 Cir. 1962, 304 F.2d 53,

cert, den’d 1963, 372 U. S. 924, 83 S.Ct. 741, 9 L,Ed.2d

729. Judge Rives was the author of both opinions;

the author of this opinion was on both panels. In

each case the attorneys for the Negro defendant did

the exhaustion requirement. Application of these principles to a

given set of facts produces identical results. Thus, . . . a

habeas court could hold that by failing to exhaust a remedy

no longer available, petitioner has waived his procedural rights

and has created an adequate and independent state ground for

his continued detention. No matter which theory is used, peti

tioner is denied habeas corpus relief for failure to employ a

presently unavailable remedy. Once it is decided, however,_ that

the exhaustion requirement applies only to presently available

remedies, an applicant would not be penalized under that theory

for failing to appeal if he could no longer do so. But such an

interpretation of the exhaustion requirement would be rendered

nugatory if failure to appeal were to result in a forfeiture under

the theories of waiver or adequate state ground. The danger

in regarding the doctrines separately is this possibility of anti

thetical application.” Sofaer, supra, Note 1, 39 N.Y.U.L.Rev.

78, 82.

10 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

not make a timely objection to the composition of the

jury. In spite of this non-compliance with the state

rule requiring such an objection to be made in the

early stages of a trial,14 this Court held that there

was no waiver. In Goldsby “we held that the conduct

of Goldsby’s counsel without consultation with his

client did not bind Goldsby to a waiver of his consti

tutional right to object to the systematic exclusion of

members of his race from the trial jury.”15 With

regard to the grand jury, Judge Rives observed that

systematic exclusion of Negroes from a grand jury in

volves consequences less serious than the consequences

of their exclusion from a trial jury. The Court held

that the petitioner had waived any objection to the

grand jury. In discussing this case in Seals, however,

Judge Rives pointed out: “ [In Goldsby] the evidence

to support objections to the composition of the jury

was entirely unknown to the defendant Seals, who

was at no time even consulted by his attorney on this

subject. Further, that evidence was not known to the

attorney who defended Seals. Finally, that evidence

was not ‘easily ascertainable’ ” . 304 F.2d at 69. In

Seals, therefore, the Court held that there was no

waiver of the constitutional objection to the composi

tion of either the petit jury or the grand jury.

We approve of the holdings in Goldsby and Seals.

The important fact in each case was that the attorney

for the Negro defendant did not consult his client with

„ , See Seals v. State, 1961, 271 Ala. 622, 126 So.2d 474, cert,

dend, 366 U. S. 954; Cobb v. State, 1962, 218 Ga. 10, 126 S E 2d

231, cert, den’d 1963, 371 U. S. 948, 83 S. Ct. 499, 9 L.Ed 2d 497

15 United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 5 Cir. 1962, 304 F2d

53, 69.

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 11

regard to his decision to refrain from making an attack

on the jury system; and in Seals the evidence relating

to systematic exclusion of Negroes from the juries was

unknown to the defendant’s attorney, Goldsby has

been construed as holding that in a capital case

“before a defendant will be deemed to have waived

his objection to trial by a petit jury infected by an

unconstitutional exclusion for race, the record must

show that the defendant, not just his counsel, took

the action deliberately and after advice” .16 Adams v.

United States, 5 Cir. 1962, 302 F.2d 307, 314 (dissenting

opinion). Goldsby, however, does not go that far.

The opinion makes this significant reservation:

“In ordinary procedural matters, the defendant

in a criminal case is bound by the acts or non

action of his counsel. . . . It might extend to

such a waiver even in capital cases, where the

record affirmatively shows that the particular

jury was desired by defendant’s counsel after

conscientious consideration of that course of

action which would be best for the client’s

cause.” 263 F.2d 71 at 83.

The unusual example—for an exclusion case—which

Judge Rives gives is the only type of exclusion situa

tion where there is a possibility of a true waiver * 50

16 Cf. “Before any waiver can become effective, the consent of

government counsel and the sanction of the court must be had,

in addition to the express and intelligent consent of the de

fendant.” Patton v. United States, 1930, 281 U. S. 276, 312,

50 S.Ct. 253, 74 L.Ed. 854. “ [Clourts indulge every reasonable

presumption against waiver of fundamental constitutional rights” ,

and “ do not presume acquiescence in the loss of fundamental

rights” . Johnson v. Zerbst, 1938, 304 U. S. 458, 464.

12 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

based on a free option.17 When a defendant’s attorney

prefers a particular jury, there is “a voluntary choice

between two meaningful alternatives” .18 Absent this

preference, there is no voluntary choice to relinquish

the right to a fairly constituted jury when the right

must be relinquished in order not to imperil the

defense.19 Even in a situation where a defendant’s

attorney has a considered preference for a particular

jury, under the decisions the attorney must consult

with his client and the defendant must “understand-

ingly and knowingly” forego his federal claims before

a waiver would be established. But if the defendant

lacks the capacity “understandingly and knowingly”

to waive his right, it is an empty gesture to require

consultation and it is meaningless to speak of waiver.

17 For example, in Carruthers v. Reed, 8 Cir. 1939, 102 F.2d

933, cert, den’d 1939, 307 U.S. 643, the trial attorney knew certain

jurors and believed that the defendant would receive a fair trial.

18 Comment, supra, note 1, 72 Yale L. Jour, at 567.

19 Professor Reitz brings out clearly the “great difficulties”

that “arise in this attempted transition from ‘an intentional

relinquishment or abandonment of a known right of privilege’ ”

[Johnson v. Zerbst] to a case involving an abortive state pro

ceeding. ( “An abortive state proceeding has occurred when a

state criminal defendant, at some time in the past, had an op

portunity to present to his own state’s courts any question rele

vant to the power of the state to hold him in custody but lost

that opportunity can no longer seek any relief there.” ) “The

most that was waived was the right to review in the state Su

preme Court. It takes some additional extrapolation to make

that equivalent to waiver of the underlying federal right.” Reitz

supra, note 1, 74 Harv. L. Rev. 1335. See also Moyers v. Yar

brough, Bis Vexari: New Trials and Successive Prosecutions, 71

Harv. L. Rev. 1, 6 (1960). In discussing “waiver” of the

guarantee against double jeopardy, the authors wrote, “Yet it is

obvious that a waiver rationale here, as elsewhere, serves only

to state the conclusion without explaining the reason for it

See also Sofaer, supra, Note 1, 39 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 78, 83-91; Com

ment, Waiver of the Privilege Against Self Incrimination. Note,

Waiver of the Privilege Against Self Incrimination, 14 Stan L

Rev. 811 (1962).

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 13

To return to the case before us, here the attorneys

for the petitioners are able, conscientious, experienced,

court-appointed white lawyers.20 The petitioners are

ignorant Negroes whose frame of reference could not

have included any comprehension of the traditional

constitutional rights incident to a fair trial. Davis is

illiterate and Whitus semi-illiterate. The Attorney

General for the State, in his brief, makes a point of

this in order to further his contention that the defend

ants are bound by the fictitious waiver of their at

torneys:

“It is evident from the record that defendants

were men of lesser intelligence at least in their

understanding of the law and were completely

dependent upon their attorneys for a proper

defense. . . . The testimony of the appellant,

Leon Davis, at the first hearing before the

District Court for the Southern District of

Georgia lucidly points out that he does not

comprehend the nature or meaning of the

Constitution or the rights provided thereunder

and is, in fact, entirely dependent on counsel

for his defense.”

In these circumstances, it is unrealistic for the Court

to attach significance to the presence or absence of

consultation of the attorneys with the defendants and

20 The brief of the Attorney General states:

“ The court will remember that Honorable P. Walter

Jones has represented Phil Whitus from the outset of this

case. A fleeting glance at the history of this case proves

conclusively that Mr. Jones has exerted every effort in be

half of the appellant and is to be commended for his un

selfish and tireless defense of this individual.”

14 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

the presence or absence of express consent by the

defendants to the so-called waiver. For the petitioners

in this case, these protections are simply not adequate

safeguards against forfeiture of constitutional rights.

The defendants would have been no better off after

consultation than before; had they been consulted and

had they given instructions contrary to the attorneys’

advice, they would have been worse off. As the

Supreme Court of Georgia said in Cobb v. State, 1962,

218 Ga. 10, 126 S.E.2d 231, cert, den’d 1963, 371 U. S.

948, 83 S. Ct. 499, 9 L.Ed.2d 497:

“Where, as here, the defendant knows nothing

of his rights or whether it would be stra

tegically wise to waive them in certain situa

tions, it would be to require a vain and useless

thing1 that he personally consent to such waiver.

If appointed counsel had been compelled to

consult and be controlled by the directions

given him by his client, who was only fifteen

years old, and according to his own insistence,

knew nothing of law, courts or legal procedure,

his usefulness would have been destroyed and

the defendant would not have been represented

by counsel within the meaning of Art. I, Sec.

I, Par. V of the Georgia Constitution (Code

Ann. §2-105).” (Emphasis added.)

Cobb involved facts very similar to the facts in the

instant case. The futility of requiring an express

waiver from the fifteen year old Negro defendant led

the Georgia Supreme Court to conclude that “the

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 15

waiver may be made on his behalf by counsel ap

pointed by the court to defend him.”

Here, as in Cobb, the evidence showed no consulta

tion between the attorneys and the petitioners on

waiver and here too the petitioners lacked the com

prehension to make an intelligent waiver. If, notwith

standing, the State may treat the attorneys’ inaction

as implied “waiver” , it is because the State, for its

purposes, may establish a ground rule that orderly

procedures compel a client to be bound by his lawyer’s

action and inaction21 and require also that objections

to juries be urged in the early stages of a trial; other

wise, state procedures would be circumvented.

Such a state rule, so reasonable on its face, is an

“ independent and adequate state ground”,22 which

21 Popeko v. United States, 5 Cir. 1961, 294 F.2d 168; Kennedy

v. United States, 5 Cir. 1958, 259 F.2d 883.

22 In Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 429-32, the Court commented:

“ The fatal weakness of this contention is its failure to recognize

that the adequate state-ground rule is a function of the limita

tions of appellate review. . . . And so we have held that the

adequate state-ground rule is a consequence of the Court’s obliga

tion to refrain from rendering advisory opinions or passing upon

moot questions. U But while our appellate function is concerned

only with the judgments or decrees of state courts, the habeas

corpus jurisdiction of the lower federal courts is not too con

fined. The jurisdictional prerequisite is not the judgment of a

state court but detention simpliciter. The entire" course of de

cisions in this Court elaborating the rule of exhaustion of state

remedies is wholly incompatible with the proposition that a state

court judgment is required to confer federal habeas jurisdiction.

And the broad power of the federal courts under 28 U.S.C. §2243

summarily to hear the application and to ‘determine the facts,

and dispose of the matter as law and justice require,’ is hardly

characteristic of an appellate jurisdiction. Habeas lies to en

force the right of personal liberty; when that right is denied and

a person confined, the federal court has the power to release

him. Indeed, it has no other power; it cannot revise the state

court judgment; it can act only on the body of the petitioner.

. In Noia’s case the only relevant substantive law is

16 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

Federal courts generally should respect. But, as

stated in Fay v. Noia, “Federal courts have power

under the federal habeas corpus statute to grant relief

despite the applicant’s failure to have pursued a state

remedy not available to him at the time he applies.”

372 U. S. at 398.

The overriding duty of a federal court to protect the

federally guaranteed rights of the individual citizen

impels the court to inquire into the reasonableness,

the constitutionality, of the state rule. “Reasonable

consequences attached by the states to a failure to

comply with reasonable rules must accordingly be

respected. . . . But this assuredly does not mean

federal—the Fourteenth Amendment. State law appears only in

the procedural framework for adjudicating the substantive federal

question. The paramount interest is federal. Cf. Dice v. Akron,

C. & Y.R.Co., 342 U. S. 359. That is not to say that the States

have not a substantial interest in exacting compliance with their

procedural rules from criminal defendants asserting federal de

fenses. Of course orderly criminal procedure is a desideratum,

and of course there must be sanctions for the flouting of such

procedure. But that state interest ‘competes . . . against an

ideal . . . [the] ideal of fair procedure.’ Schaeffer, Federalism

and State Criminal Procedure, 70 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 5 (1956). And

the only concrete impact the assumption of federal habeas juris

diction in the face of a procedural default has on the state

interest we have described, is that it prevents the State from

closing off the convicted defendant’s last opportunity to vindi

cate his constitutional rights, thereby punishing him for his de

faults in the future.” Ct. Williams v. Georgia, 1955, 349 U. S.

375, 393-405, 75 S.Ct. 814, 99 L.Ed. 1161. In McKenna v. Ellis,

5 Cir. 1960, 280 F.2d 592, 603 rehearing denied and opinion

modified, 289 F.2d 928, cert, den’d 1961, 368 U.S. 877, this Court

granted habeas corpus although the prisoner had not complied

with Texas procedure. We held: “Article 543 of the Texas Code

of Criminal Procedure sets forth very clearly the requirements

for a continuance. We do not question the propriety, the reason

ableness, the constitutionality of Article 543. ‘Such detailed

and technical requirements of a motion for continuance, no doubt,

serve a salutary purpose in a proper case, but they cannot

justify putting a defendant to trial when he has been given no

fair opportunity to secure the attendance of his witness.’ ”

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 17

that every last technicality of state law must be

sacrosanct.” Hart, Foreword: Time Chart for the

Justices, 73 Harv. L. Rev. 84, 118 (1959). Professor

Hart’s comments on a state rule that the escape of a

prisoner nullifies his motion for a new trial23 are apt

here:

“The reasonableness of the state rule and,

even more, the reasonableness of its application

in the particular circumstances of the case

cried aloud for questioning. Life was at stake.

The constitutional rights which the prisoner

asserted went to the very jugular of a system

of ordered liberty—the right to be judged in

an orderly trial before an unprejudiced tri

bunal rather than by the whipped-up emotions

of the community. States may punish an

escape as a crime. But surely not all rights

to a fair trial can become forfeit because of it.

Especially are doubts stirred when the escape

' in question can be viewed as a form of self

protection from the very community hostility

against which the prisoner had previously pro

tested in vain by lawful means. These con

siderations called for close scrutiny of the

opposing considerations advanced by the state

to show that the forfeiture it had decreed was

necessary for the due enforcement of law.”

73 Harv. L. Rev. at 116.

23 See Irvin v. Dowd, 1959, 359 U. S. 394, 79 S.Ct. 825, 3 L.Ed.2d

900

18 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

III.

This ■ case is “one of those extraordinary cases” Mr.

Justice Frankfurter may have had in mind in the

caveat to his discussion of waiver in Brown v. Allen:

the federal “claim goes to the very foundation of [the]

proceeding” . When Negroes are systematically ex

cluded from juries, the fictitious waiver rule puts

Negro defendants, and only Negro defendants, to a

choice of evils that deprives them of an effective

remedy.

A. We know what happens when the attorney’s

inaction is treated as a waiver of the exclusion issue:

the Negro defendant loses the benefits of a trial by

his peers. We quote two sentences on the subject

from a Supreme Court opinion in 1879:

“The very idea of a jury is a body of men com

posed of the peers or equals of the person

whose rights it is selected or summoned to

determine; that is, of his neighbors, fellows,

associates, persons having the same legal

status in society as that which he holds. . . .

[C]ompelling a colored man to submit to a

trial for his life by a jury drawn from a panel

from which the State has expressly excluded

every man of his race, because of color alone,

however well qualified in other respects, is

. . . a denial to him of equal protection

of the law.” Strauder v. West Virginia, 1879,

100 U. S. 303, 309, 25 L. Ed. 664.

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 19

B. We believe that we know what happens when a

white attorney for a Negro defendant raises the ex

clusion issue in a county dominated by segregation

patterns and practices: both the defendant and his

attorney will suffer from community hostility.

The burden of making hard decisions is one that

attorneys are used to carrying. But the burden is

exceptionally heavy when the life and liberty of an

accused depend on the weight to be given something

as imponderable as the extent of the additional anti-

Negro reaction that would be engendered by attacking

the all-white jury system. As if this were not suf

ficiently difficult, there is the intolerable complication

that the reaction against an attorney who raises the

exclusion issue may stretch from persiflage to ostra

cism. The intensity of the reaction will depend on

how bad racial relations are in the particular county,

the standing of the defendant’s attorney at the bar

and in his community, the happening of unpredictable

local events, and coincidental accidents of history. The

reprisals may be real or chimerical; if chimerical, 'they

may seem real to any particular attorney. All of this

adds up to pressures which may, consciously or sub

consciously, affect an attorney’s measured evaluation

of which evil is the lesser evil in this Hobson’s choice

of evils.24 Later, should there be a post-conviction

24 “In response to a questionnaire prepared by the Journal

and sent to 100 southern lawyers whose names were picked at

random, 20 stated that they felt the Fifth Circuit was correct in

taking judicial notice that lawyers in the South rarely raise the

issue of jury exclusion. Fourteen felt the Fifth Circuit was in

correct either because there is no jury exclusion (9) or because

the issue is raised when the facts so warrant (5).

“ In answer to the question whether you would ‘raise at trial

level the issue of systematic exclusion of Negroes from the

20 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

habeas corpus proceeding, the attorney’s knowledge

that his integrity may be questioned and his pro

fessional skill second-guessed in an antagonistic atmos

phere may cause him to slant his explanation for

making the wrong guess. The exposure of a Negro

on trial for his life to these factors destructive of

justice and federally protected rights and harmful to

the public policy of encouraging adequate legal repre

sentation of indigents is a monstrous price to pay for

the convenience to the state of the procedural rule

euphemistically termed “waiver” .25 * 26

jury, if you thought there was reasonable evidence of such

exclusion,’ 21 answered yes and 13 responded no.

“ Reasons given for the failure to raise the objection included

a desire not to prejudice the lawyer’s position in the community

(2), a desire not to prejudice the client’s interests by stirring

up community feeling against him, thereby hoping to achieve

the best result for the Negro client (11), and a feeling that it

would make no difference to the outcome of the case whether

or not there is jury exclusion (15).

“ In response to the questionnaire prepared by the Journal,

one Alabama lawyer wrote:

“ If I accepted a Negro for jury duty and put him on with

11 white men I would prejudice the white men against me

and my client.

A lawyer in Florida wrote:

“ It has been my observation and it is my present thinking

that the interests of a Negro client in the South would be

better protected by the white man than colored.”

Comment, Negro Defendants and Southern Lawyers: Review in

Federal Habeas Corpus of Systematic Exclusion of Negroes from

Juries, 72 Yale L. Journ. 559, 565 (1963).

26 “It is relevant to ask, for purposes of a corollary to the

federal exhaustion rule, whether the price of utilizing the state

remedies was too great . . . This is particularly significant in

the case of the Negro defendant who had to give up the chance

of an unprejudiced trial in order to raise the constitutional ob

jections at the time prescribed by state procedural law. In some

circumstances, the situation might be such that the defendant

could not be said to have had an effective state remedy available

to him, even though formally a method for challenging the

juries existed. But even in less extreme cases, there ought to be

serious doubt that a defendant should be put to this Hobson’s

choice with respect to a constitutionally guaranteed right, jf Not

everyone will agree that the federal courts should go to the

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 21

C. We turn now to the bases in the decision-making

process for judicial consideration of these matters.

(1) We start with a fair inference. If the segrega

tion policy in a county is so strong that Negroes are

systematically excluded from the jury system, com

munity hostility would be generated against any

“trouble-maker” who would attempt to upset the all-

white make-up of the jury system. Such hostility would

directly affect the Negro defendant. It would carry

over and affect the defendant’s attorney. Whether

horrendous or merely embarrassing, the prospect of

social extra-legal pressures distorting an attorney’s

judgment is a burden only Negro defendants bear.

(2) In Goldsby we took judicial notice of the fact

that in some areas in the deep South lawyers almost

never raised the exclusion issue.* 26 We said:

“Moreover, the very prejudice which causes

the dominant race to exclude members of what

it may assume to be an inferior race from jury

service operates with multiplied intensity

against one who resists such exclusion. . . .

Such courageous and unselfish lawyers as find

it essential for their clients’ protection to fight

against the systematic exclusion of Negroes

merits of these applications. It seems to me, however, that

entertaining them would not pose a serious threat to the general

requirement of exhaustion of state remedies, since the factors

which governed the actions of the defendants were unrelated to

the exhaustion rule.” Reitz, supra, Note 1, 74 Harv. L. Rev. at

1372.

26 McNaughton, Judicial Notice-Exerpts Relating to the Morgan-

Wigmore Controversy, 14 Vand. L. Rev. 778, 789 (1961); Mc

Cormick, Judicial Notice, 5 Vand. L. Rev. 296, 315 (1952).

22 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

from juries sometimes do so at the risk of

personal sacrifice which may extend to loss

of practice and social ostracism. As Judges

of a Circuit comprising six states of the deep

South, we think that it is our duty to take

judicial notice that lawyers residing in many

southern jurisdictions rarely, almost to the

point of never, raise the issue of systematic

exclusion of Negroes from juries.” (Emphasis

added.) 263 F.2d at 82.

The effect will, of course, be accentuated if the case

is one involving the murder of a white man by a Negro

or the rape of a white woman by a Negro or if the

timing of a trial should happen to coincide with

fevers running high because of bad racial relations.

(3) The fact, standing alone, that no Negro has

ever served on a jury in the particular county where

his case is tried strongly indicates, if it does not

create a presumption, that there was a tacit agree

ment by the bar of that county not to raise the consti

tutional issue. In such case the Negro would have no

adequate remedy, either because of the powerful

environmental factors infecting the jury system or

because of ineffective representation by counsel. At

the very least, that fact alone establishes a prima

facie case putting the burden of going forward on the

State to show that there was a true waiver; that the

non-assertion of the defendant’s constitutional right

was not caused by environmental pressures or inef

fective representation by the defendant’s attorney.

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 23

(4) This case is a doubly strong one for the de

fendant because, unlike Goldsby,27 we have the benefit

of specific testimony from Whitus’s trial attorney on

the motivation for his non-action. As we noted in

Goldsby, “Conscientious southern lawyers often reason

that the prejudicial effects on their client of raising the

issue far outweigh any practical protection in the

individual case.” 263 F.2d at 82. Here, Mr. Walter

Jones, attorney for Whitus, testified that he had hopes

for an acquittal of his client on the charge of murder,

whatever other offense he might have committed. In

the habeas corpus hearing Mr. Jones testified:

“Q. Did you confer with Phil Whitus and

receive his express permission to waive his

objection to the trial jury unconstitutionally

selected and discriminatorily selected?

“A. No, I did not.

“Q. Why did you not raise this question

on the trial of Phil Whitus in Mitchell County,

Georgia?

“A. Well, I had talked to Phil Whitus and

I conferred with the attorneys who repre

27 In Goldsby, the defendant’s first lawyer, a Negro, was willing

to raise the exclusion issue. His white lawyer refused to join

with the Negro lawyer in representing the defendant and did not

raise the exclusion issue after the Negro lawyer left the case.

The attorney’s failure to raise the issue and the lack of any

explanation could give rise to the inference that the trial counsel

was not acting in the best interests of his client. In Goldsby,

however, we said, as we do here, that sometimes raising the

issue may cause more prejudice than it is worth. The necessity

for the attorney making this choice, not just the composition of

the jury, is the constitutional vice. See Comment, Negro De

fendants and Southern Lawyers: Review in Habeas Corpus of

Systematic Exclusion of Negroes from Juries, 72 Yale L Jour.

559, 564 (1963).

24 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

sented the other defendants and I knew ap

proximately what they would testify and I

had hopes that I could obtain an acquittal

under the facts as l knew• them, and I realized

that the case had created quite a bit of noto

riety and to have brought up such a question

at the lower court would have filled the air

with such hostility that an acquittal would

have been almost impossible.

“Q. The Solicitor General asked you just

now if you requested a change of venue. Did

you have a conference with the judge con

cerning the possibility of that?

“A. No, sir. I had a conference with the

other attorneys in the case and we agreed

that he might change it to Baker County and

we were better off in Mitchell.

“Q. Would there have been the same dis

crimination in Baker County?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. As I understand, you said that the

reason for not raising the question of dis

crimination was because you thought it would

create a hostile feeling and would hurt your

client?

“A. Yes, sir.” (Emphasis added.)

The measure of the merits of Whitus’s defense and

the measure of his dilemma is that the Chief Justice

and two other members of the Supreme Court of

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 25

Georgia agreed with Mr. Jones’s theory of the case

and wrote a strong dissent.28

D. In Fay v. Noia the defendant was also con

fronted with a “grisly” choice. In that ease a de

fendant was convicted of murder. Years later, long

after his time for appeal had expired, he applied for

habeas corpus on the ground that he had been con

victed on the basis of a coerced confession. The Su

preme Court held that the petitioner’s failure to appeal

in the state court was not a waiver of his rights and

did not bar habeas corpus relief. The Court first

28 In his dissenting opinion, Chief Justice Duckworth said:

“In full recognition of the established rule of law that holds

those parties to a criminal conspiracy or enterprise, who commit

no overt act, equally guilty with those who commit the overt

acts, I am, nevertheless, simply unable to find any basis either in

law or common reason for holding this defendant guilty of murder

where all the evidence excludes any possibility of conspiracy

among the four, who included this defendant and the person who

did the killing. They had planned no robbery, theft or other

crime, and indeed had no reason to expect to see the deceased

before he went to them. Thereafter, this defendant had no

dealings, words or feelings with or toward the deceased. Why

should he want to harm the deceased? There is positively a

complete absence of even a suspicion of any motive. The slayer

committed every criminal act that caused the death. He needed

no help from this accused other than pushing the car and racing

the motor, both of which were done at his command while he

held the gun with which he later shot the deceased, who had

already been knocked unconscious by the killer. To say that this

was not enough to cause a reasonable person to fear that a

refusal to obey would endanger his life, is to ignore realities and

human nature. No act of his harmed a hair of the deceased.

Even if he was cowardly and foolish in obeying the murderer

who held a gun, this would not show his guilt of criminal desire

or intent. Human life should not be taken by the State with

such total lack of evidence of either act or intent as this record

shows. Unless he is saved by the clemency of the Pardon and

Parole Board, his life will be forfeited for a crime he never com

mitted and had no cause for wanting it committed. If this de

cision fixes the law, then every person stands in danger of being

electrocuted if a murder is committed by someone of his as

sociates even though he had no knowledge that it was going to

be done.” Whitus v. State, 116 S.E.2d at 207.

26 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

eliminated the possibliity of any express waiver: “A

choice made by counsel not participated in by the

petitioner does not automatically bar relief.” Mr.

Justice Brennan, for the majority, then explained

why Noia’s choice not to appeal was not a matter of

trial strategy or a deliberate attempt to by-pass state

procedures:

“Under no reasonable view can the State’s ver

sion of Noia’s reason for not appealing support

an inference of deliberate by-passing of the

state court system. For Noia to have appealed

in 1942 would have been to run a substantial

risk of electrocution. His was the grisly choice

whether to sit content with life imprisonment

or to travel the uncertain avenue of appeal

which, if successful, might well have led to a

retrial and death sentence. See, e.g., Palko v.

Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319. He declined to play

Russian roulette in this fashion. This was a

choice by Noia not to appeal, but under the

circumstances it cannot realistically be deemed

a merely tactical or strategic litigation step, or

in any way a deliberate circumvention of state

procedures.”

Recently a commentator has observed the analogy

between the defendant’s situation in the Noia case and

the defendant’s position in the instant case “in that

here he must choose whether to assert his consti

tutional right with a possibility of forfeiting his chances

for an unprejudiced trial, or remain silent and gamble

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 27

on the outcome of the trial with the possibility of

raising the question later if the outcome proves un

satisfactory” . Note, 16 Ala. L. Rev. 117 (1963).29 The

instant case, however, is a stronger case than Fay v.

Noia for habeas corpus relief. Noia could have exer

cised his right to appeal without suffering any consti

tutional deprivation. But here, in order for the pe

titioners to exercise their right to a jury from which

Negroes were not excluded, the petitioners had to com

promise their right to a fair trial on the merits of

their defense.

IV.

We summarize. Taking waiver as the “intentional

relinquishment or abandonment of a known right or

privilege” , the facts show that the petitioners made no

“deliberate” , meaningful waiver of their objection to * So.

29 The note is on Ex parte Aaron, Ala. S.Ct. 1963, 155 So. 2d

334. On the authority of Seals v. State, 1961, 271 Ala. 622, 126

So. 2d 474, cert, den’d 1961, 366 U. S. 954, 81 S.Ct. 1909, 6

L.Ed.2d 1246, the Court held that the defendant, a Negro indicted

for the rape of a white woman, had waived the systematic

exclusion issue. At arraignment, in answer to a question from the

trial judge, the defendant’s attorney stated that they did not

intend to attack either the grand jury or the petit jury venire

because of “ the racial make-up of such grand jury or petit jury

venire” . The note concludes, “Thus, the Alabama court has yet

to recognize the principle advanced in the Noia case—that even

a knowing failure to assert this particular constitutional right

does not constitute a waiver, or, more concisely, that there can

be no waiver at the present time of this constitutional right. . . .

Would it not be better to align [Alabama’s] concept of waiver

with that set out in the Noia case, thereby enabling defendants,

by coram nobis in state courts, to assert the right for the first

time, rather than forcing an unsuccessful defendant into the

federal courts on habeas corpus when the obvious result will be

a federal decision overturning a decision of our highest state

court, with the chafing effect it will undoubtedly have on federal-

state relations?” Note, 16 Ala. L. Jour. 117, 123 (1963).

28 Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr.

systematic exclusion of Negroes from the juries in

Mitchell County. Taking “waiver” as a formula stand

ing for the rule that non-assertion of an objection to

state procedures vitiates the objection, we hold: under

Fay v. Noia, in a federal habeas corpus proceeding the

court cannot permit a state ground rule to frustrate the

federally guaranteed right to a fair trial before a

fairly constituted jury. We do not say that “no waiver

can be effective if some adverse consequences might

reasonably be expected to follow the exercise of that

right.”80 We say that the doctrine of fictitious waiver

is unacceptable when the state compels an accused

person to choose between an unfairly constituted jury

and a prejudiced jury. In short, while giving full ef

fect to the holding of the majority in Fay v. Noia the

Court has attempted to answer the basic question Mr.

Justice Harlan asked in his dissenting opinion:

“Whether the choice made by the defendant is one

that the State could constitutionally require.”30 31 We

hold that the State could not constitutionally require

the petitioners to make a guess and a gamble between

two evils. This burden, which only Negro defendants

bear, violates the requirements of due process and

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment.

* * *

As in Goldsby and Seals, the Court expresses its

present opinion that a period of eight months from and

after the entry of this judgment or its final test by

certiorari, or otherwise, will be sufficient to afford the

30 Pay v. Noia, 1963, 372 U. S. 391, 472 (dissenting opinion).

31 Ibid.

Whitus, et al. v. Balkcom, Jr. 29

State an opportunity to take the necessary steps to

reindict and retry the petitioners. Any such reindict

ment must of course be by a grand jury from which

Negroes have not been systematically excluded, and

any such retrial must be before a jury from which

Negroes have not been systematically excluded, or be

fore some court or tribunal so constituted as not to

violate the petitioners’ constitutional rights. For the

guidance of the parties, the Court expresses the present

opinion that if petitioners are reindicted and retried

and if any question should arise as to the legality or

constitutionality of such indictment or trial, that should

be decided not upon the present petition but in the

regular course by the Courts of the State of Georgia,

subject to possible review by the Supreme Court of the

United States.

The judgment of the district court is reversed, judg

ment here rendered in accordance with the holdings of

this opinion, and the cause remanded for any further

proceedings which may be found necessary or proper.

REVERSED, RENDERED, and REMANDED.

CARSWELL, District Judge, concurring specially:

Sharing fully the Courts’ view that there was no

meaningful waiver by these appellants of their basic

Constitutional right to face trial by jurors selected

without systematic racial exclusion, I, therefore, con

cur in the basic holding of the Courts’ opinion.

Adm. Office, U. S. Courts—E. S. Upton Printing Co., N. O,, La.