Attorney Notes

Working File

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes, 1983. 7fed5960-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e06ff1f-9c0c-4cf5-bcb3-2a263b8b1080/attorney-notes. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

tVr*-O* I

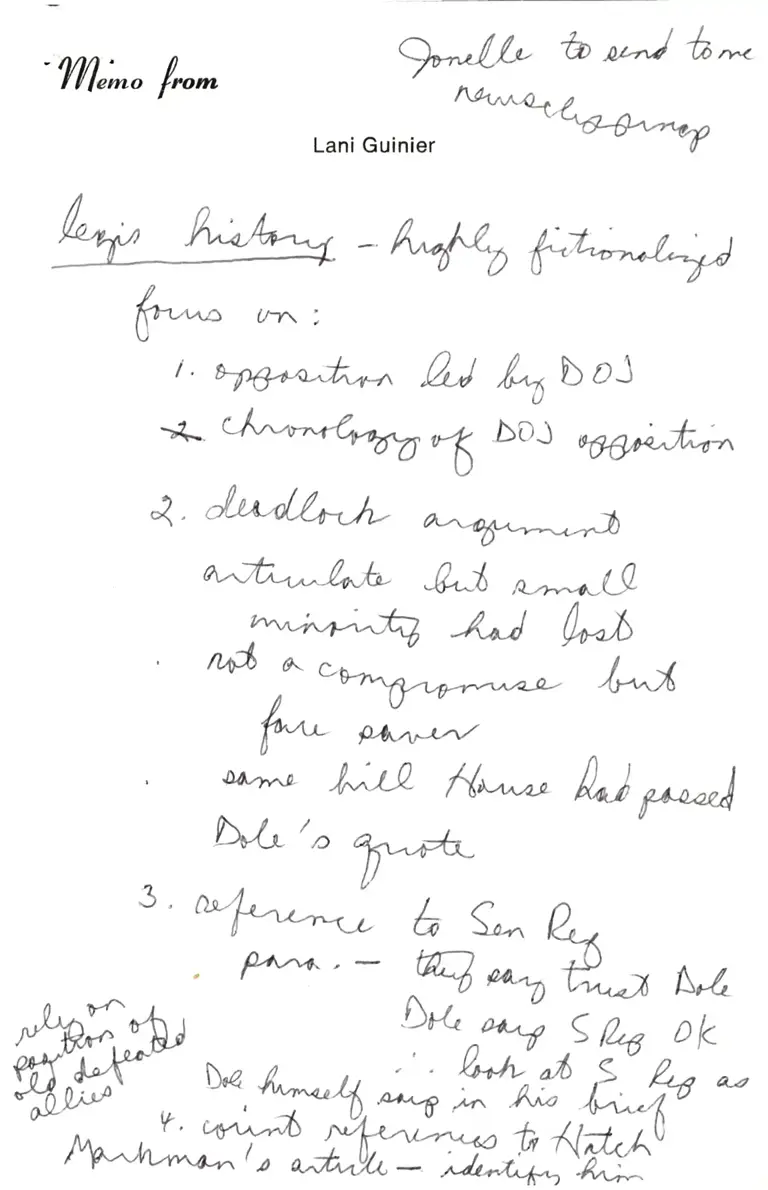

Lani Guinier

"t"*fuf

fu l*^* - A^4'zD {*t-*L-/)

9*U* b Ar) h*-T/b" /**

fu^" r.t,:

t, *7t6^"-**^ n/ /r,AOl

>L %-6boJ Wr"^*--.

t , -',ln*to A"tr"b p"tr

h s<

@^o

^ /r^1L*4" /,"1 (

k*, t* ,]*-,,,- l- ^rl

2, Dd d,^fi,^rq?/o D

3' 7 4, ^rM hl

"/^#,n ffl A

A^r-,,'.^/

T. kl 44r.*r^ v . u6