Correspondence from Schnapper to Hebert; United States' Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Correspondence

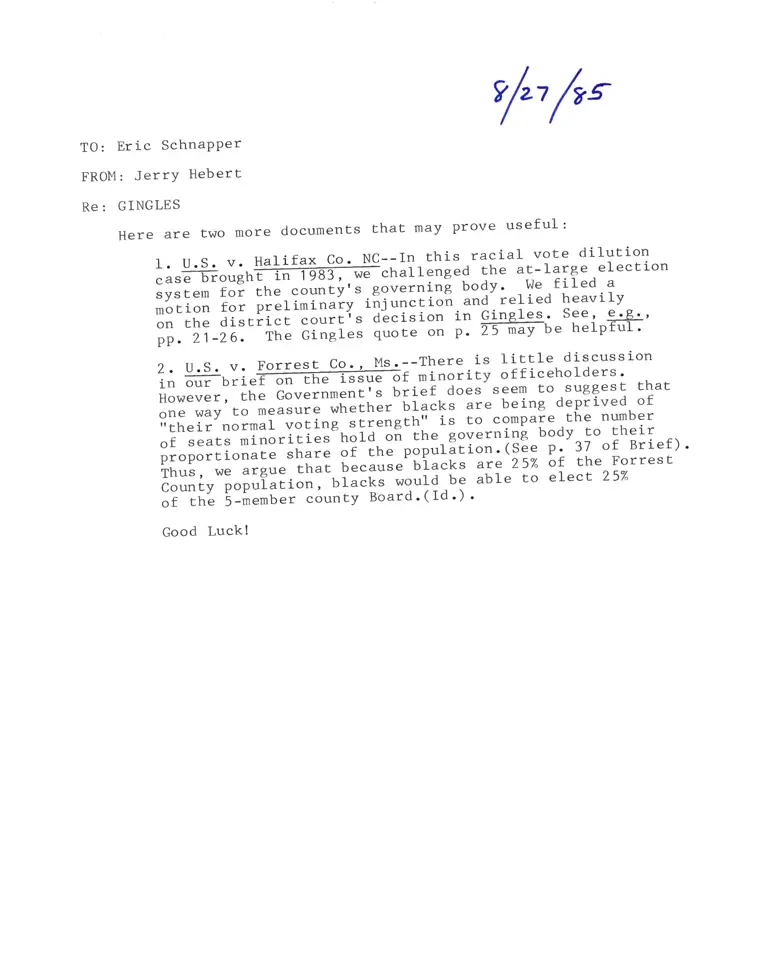

August 27, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Correspondence from Schnapper to Hebert; United States' Motion for Preliminary Injunction, 1985. 9ccc6755-e392-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9e1a8c4d-f79c-4e52-871c-42721456b665/correspondence-from-schnapper-to-hebert-united-states-motion-for-preliminary-injunction. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

*,/,,

TO: Eric SchnaPPer

FROI'{: JerrY Hebert

RC: GINGLES

Here are two more documents that may Prove useful:

I.U.S.V.HalifaxCo.NC--Inthisracialvotedilution

case #.Ignfficrraitengea !h" at-Iarge election

system fol the t""i[i"".r:Y:1::l; bodv' we filed a

motionforpreliminaiyii5unctioilandreliedheavily

on rhe district """iils

dLcision in Glngles'_see, €'8'';

pp.il-ie-._TheGinglesquoteonp.ffiuehelpful.

2 . U. S . V. Forrest Cq ' , Ms ' --r1.rt1:-, l-"- ll::l:":+::::: tt"

Hioli"ffif minoritv of f iceholders 'in ouril:-:*:':'l;: il":fi*;;;;; iii"i a'"" -"::T-:',::9?.".:: :?"'l::T:;' .1"["II;;;;;;rrlr-tir;l: ::"^::::9^o:f:'X:,S'::3:f;"Y:'";;r;i' voting "tt"''glr'l' i" -t?-:?:l"I:,:h:^":il:?l"tneIr nof llliar vuLrrrs ue!s..ov-- ' ; body to their

oi--"!rt" minorities hold. on !h:., q:Y:I")l=^ n 2,i of Bri;:"ff::i,Ili:'J;I: F _!,:],:i:ll:i:l:(;i; t;. ?1.'F"::::[)''d;::' #";;;;"";;;; i""'"""' uiic5i 1i? ^2??: 3f ^11", f;"'"'tlXiir-o"i"il.i""l-ur""r'" *9"19,0: able to elect 25%

;;1;'" ;:;;;;' countY Board' ( rd ') '

Good Luckt

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

WILSON DIVISION

HORACE JOHNSON, SR. , eE trl., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v.

HALIFAX COUNTY, €t al.,

) cIvIL ACTION NO.

) 83-48-Crv-8

\(

\

Defendants. t

)

)

)UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

v.

HALIFAX COUNTY, €t al.,

)

Plaintiff , ) CML ACTION NO.

) 83-88-crv-8

)

)

)

)

Defendants. )

)

UNITED STATES I II{OTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJT'NCTION

PlainEiff tnited States hereby moves, Pursuant to Rule

65, Fed. R. Civ. P., for a prelimlnary injunction barring

elections for members of the Halifax County Board of Coqnty

Commissioners under an at-large election system and requiring

electlons in 1984 under a court-ordered, interim plan. This

motion ls based upon our clairn under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. L973, and is subnitted for

resolution by the single judge assigned to hear CounE One of

our Complaint.

In support of this motion,

upon the accompanying Memorandum

Exhibirs filed by rhe plainriffs

Coun ty.

Dated rhis 4'^ ary of June,

SAMUEL T. CURRIN

United States Attorney

the United States .relies

and Exhibits, as well as

in Johnson v. Halifax

1984.

Respectfully submitEed,

WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

AssisEant Attorney General

STEVEN H. ROSENBAI,M

POLI A. MARMOLEJOS

Attorneys, Voting Sectlon

CiviI Rights Division

Department of Justice

10th & Pennsylvanla Avenue, N. W.

Washington, D. C. 20530

(2O2) 272-629s

PAUL F. HANCOCK

IN THE UNITED STATES

EASTERN DISTRICT

COURT FOR THE

CAROLINA

CIVIL ACTION NO.

83-48-CrV-8

DISTRICT

OF NORTH

DIVISIONWILSON

HORACE JOHNSON, SR., et al.,

Plaintiff s,

v.

HALIFAX COUNTY, et al.,

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Defendants.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO.

83-88-CrV-8

v.

HALIFAX COUNTY, et 41.,

Defendants.

MEMORANDII,T IN SUPPORT OF UNITED STATES'

MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

The United States seeks a preliminary injunction

concerning the 1984 elections for the Halifax County Board of

County Commissioners in order to ensure Ehat the right to

vote of black citizens of Halifax County is not denied or

abridged in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

as amended. 42 u.s.c. L973c (hereinafter, "section 2"). We

request that this Court enjoin elections under the at-large

election system and then require elections to be held under a

court-ordered, interim Plan.

Halifax County's existing at-large election system for

county commissioners was adopted in L97L, 1971 N.C. Sess.

Laws 681 (hereinafter, "Chapter 681") and implemented in

violation of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. 42 U.S.C.

L973c (hereinafter, "Section 5"). On April 19, L984, the

three-judge court empanelted to hear the Section 5 challenge,

enjoined defendanEs from holding any county commissioner

election pending the Attorney General's determination on the

county's Section 5 submission and further order of the court.

On May 16, 1984, the Attorney General lnterposed an objection

under section 5 to chapter 681. Halifax County, on Ehe

following d"y, filed suit seeking Section 5 preclearance from

the DisCrict CourE for the District of Columbia. Under the

Voting Rights Act, this Court must defer ruling on our claim

thac the at-large election system adopted in Chapter 681

violates Section 2 and the Constitution pending completion of

the section 5 review' connor v' !'Ig-l-Lgr '

1421 u's ' 656 (1975) '

The sysEem in effect prior to the adoption of Chapter 681

was also an at-large election system. under that system,

county commissioners were nominated and elected on an aE-

large basis, with one commissioner elected from each of the

five residency districts. County commissioners were elected

to serve four-year, staggered terms' The major difference

between this system and the Chapter 681 system is that Chapter

681 added a sixth commissioner Eo be nominated and elected on

an at-large basis from the Roanoke Rapids Townshlp residency

rliscrict.

.Z

,t

The five-member at-large system which the county proposes

to use in 1984 has not been implemented in many years and

that system elearly possesses the same racially discriminaEory

features which the Attorney General for:nd Present ln the L}TL

readoption of at-1arge elections. Since this Court must

decide whaE election plan will be uti]ized this year, rre

believe thaE the court should scruEintze closely the at-

large structure to de;ermine if it complies with federal Iaw.

As we demonstrate in this t'temorandum, the factors

,which Congress considered relevant in evaluating an aC-large

ele.cgion system indicate thaL Ehe plan before the court

violates Section 2. In light of the allegation Ehat the

at-large system was adopted and has been maintained for

racially discriminatory reasons, it certainly would dtsserve

the public interesE for this Court to approve lmplemenEati.on

of such a system, even on an lnterim basis'

r. PBOCEDURAL HTSTORY

a

The united states flled this suit on october 6, 1983.

Count Ong of our eomplaint claims that the at-large electlon

system for electing members of Ehe Hallfax County Board of

county commissioners violates section 2, and the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments of the ConstiEutlon. Count Two of our

complaint alleges that defendants have violated section 5 by

implementing voting changes made since November 1, L964,

concerning the method of eleccing county commlssioners

-3

r^rithout obtaining the preclearance required by Section 5.

Our claims under Count One are before this Court, while our

claims under Count Two are before a three-judge court

The United States' challenge Eo the at-large election

system has been consolidaEed wich @. v. Halifax

County, et al., C.A. No. 83-48-CIV-8 (E.D. N.C-). Discovery

is scheduled to close in the consolidated caaes on September 1,

1984.

On April Lg, 1984, the three-judge court enJoined

defendants "from conducting any primary or Seneral elecEions

for members of the Halifax County Board of Conmissioners on

May 8, 1984, oE at any other time, pending further orders of

this court." On May 16, the Attorney General inEerposed a

timely objecgion trnder Secfion 5 to the L97L readoptlon and

expansion of the at-large election system, Chapter 681, but

did not object to the use of staggered, four-year terms' 1968

N.C. Sess. Laws 839. Lt Pending before the three-judge

I-

cour-t are Ehe Suburission for the United States on Relief for

Defendants' Violation of Section 5 of Ehe Voting Rights Act,

Defendants' Motion to Dissovle Three Judge Court and Johnson

Plaintiffs' I"l0Eion for IntervenEion and Motion for Interim

Re lie f.

suit in the District

eourt for'the'District of Coiumbia seeking a declaratory

;;;il";;-Eh;; r["-"ori.,g cr,ant."-o.""sionEd by rh" 1971 law

do noE have ; iaci_ally ii".riilinatory purposg ald will not

have a racially-;i;;;irni"ac"iy "if..t

'in violation of Section 5'

Halifax Cou.,ty'r. tlnited Siaii:s, C.A. No. 84-1551 (D'D'C' ) '

tiffidueilffilre8+.

-4

On May 29, L984, the

preliminary injunccion based

II

Johnson plaintiffs moved for a

upon their claims r-mder Section 2.

. FACTS 2/

A. Background

Halifax County is a large, predominantly rural county

in northeastern North Carolina. According to the 1980 Census, 3/

as corrected, 4l Halifax County had a population of 55,076, of

whom 26,811 (48.72) were white and 26,599 (48.32) were black.

The voting age population in 1980 was 38,051, of whom 20,28O

(53.3%) hrere whiEe and L6,765 (44.L7") lrere black- Ex. 3, at

4. In 1980, there hlere 24,634 registered voters, of whom

L5,669 (63.6%) were white and 8,5I3 (34.67") Irere black. The

black voter regisEration raEe was 50.8 Percent, whereas the

white voter regisEraEion rate lilas 77.3 percent. Ex. 4, App. C.

ccomPanYing this Memorandum'

-App." refers to an Appendix Eo an Exhtbit'

3/ Exhibir 1 contains copies of various tables from the 1980

eensus, upon which we rely. The tables are ltsted on the

ii;;c iaga of Ex. l. We iequest thac-this Court cake.judicial

""ii""'oE

these tables purstiant to Rule 201 of the Federal

Rules of Evidence.

4/ By letEer daEed l_,lay- g, 1984, Ehe.Direct.or of the Bureau

oh rha Census advised ttre-Assisiant Attorney General- for the

ai"i1-Rights Division, DeparEment of Justice, that Ehe repo-rted

p-pulati5n count and raciil breakdown for Conoconnara Township,

it"iifr* County vrere incorrect and provided corrected figures.

C.py-"itacheJ'as Ex. 2. Populatiol compglations rePorted in

Chis l,lemo."rrJrr, Ehe Declarition of Natalie Govan (Ex.'3),

,"J-tn" Declaraiion of Allan J. Lichtman (Ex. 4) ineorporate

the corrected data.

-5

The voters of Halifax County have not elected a black

candidate to the Board of Cor:nEy Commissioners in Ehis century.

Ex. 5, Ans. to Johnson Interr. No. 6, at 4.

The county has L2 townships, ranging in 1980 populaEion

from 5L7 to 20,340, Roanoke Rapids, which is Ehe township

with the largest population, is Ehe only township with a

white populaEion majority (79.47">. Ex. 3, aE 4.

In 1980, 60 percent of the whites in Halifax County lived in

Roanoke Rapids Township, while 85 percent of Ehe county's

blacks lived in the other eleven townships.

The members of the Halifax county Board of county

Commissioners were nominaEed and elected on an at-large basis

for two-year, concurrenE terms from 1896 through L944' 1895

N.C. Sess. Laws 135; 1903 N.C. Sess. Laws 515. Beginning in

Ehe Lg44 elecEions, the county was divided into five districts

based upon township lines. Each district nominated a county

commissioner; general elections were sti11 held on an at-large

basis. 1943 N.C. Sess. Laws 317. This system of nominaEion by

district buE election at-large operated essentially as a

single-member discrict sysEem because nomination by the

Democratic Party virtually assured election'

2t

this

?esults of the f960 referendum,

subsectlon, as well as Ehe

appear in Ex. 5.

B. Method of Electing the Board of Countv Commissioners

-6

The district nomination meEhod lasted from L944 until

1960, when the county reverted to a system of at-large

nomination and election. 1959 N.C. Sess. Laws 1041. In

1960, voters in Halifax County were allowed to choose between

an at-large system with or without residency dlstricts. Voters

were not allowed to choose to retain the district nomination

system that had been in effect since L944. Ibid. By a vote

of 7 ,255 to 2,6LL, the voters chose an at-large systqm with

residency districts. Ex. 6.

Since 1960, Halifax County has boch nominated and

elected county commissioners on an aE-large basls, with

at least one commissioner from each of five residency

districts. In f968, the terms of courty commissioners elere

staggered and increased from Ewo years to four years. L967

N.C. Sess. Laws 839. Even though this change was irnplemenEed

in f968, the preclearance required by Section 5 was not obtained

until May 16, 1984, when the Agtorney General declined to

interpose an objecEion.

In Lg7L, the state legislature readopEed and expanded

the at-large election sysEem by adding a sixth commLssl'oner

who would reside in Roanoke Rapids Township but be nominated

and elec;ed on an at-large basis. 197I N.C. Sess. Laws 681'

-7

The county has implernented this change since L912, although

it had not sought precrearance under section 5 before this

suic was filed. On May L6, L984, the Attorney General

interposed a timery objection under section 5 to the voting

changes occasioned by the L97L law. rn addressing the county's

readoption and expansion of the aE-large electlon system, the

Section 5 objecEion states:

While we have noted the submisslon's

statement that Chapter 681 was adopted 1to

remedy malapportioned residency districts,

the county has presented no adequate

explanation for adopting Ehe method chosen.

The county commission admittedly considered

oEher alternatives but those other alternatives

and the reason(s) for their rejection have

not been identified. Several obvious

options, such as eliminating residency

disEricts (thereby allowing single-shot

voting) or adopting a single-member districE

election system, would have enhanced black

voting strength yet apparently were rejecEed

in favor of the Chapter 681 alternative which

mainEained black voting strength at a ninimum

level. There ls no evidence that black

citizens were consulted about Ehe malapportion-

ment issue, nor \f,as it submitted to the

voters in a referendum as has been the pasc

procedure for rnodifying the method of electlng

the county commission.

Although the five-member at-large election plan whieh

!'ras in force and effect as of November 1, L964, contains the

same racially discriminatory features as the plan to which

Lhe Attorney General objected, Section 5, by itself, does not

preclude use of the five-member p1an. See City of Rome v.

united srares, 446 U.S. 156, L82 (1980). That system requires

at-large nomination and election of five commissioners, with

-8

Carolina voEers approved "constitutlonal amendments specifically

designed to disenfranchise black voters by irnposing a poll

Eax and a literacy test for voting with a grandfather clause

for the literacy test whose effect was to limit the

disenfranchising effect to blacks." Gingles, supra, slip op.

at 27. The following year, the legislature ensured that

those devices would have their full effect by requiring a

reregistration of all voters subject to the poll tax and

liceracy test. f901 N.C. Sess. Lar{s 89, SS12 and 13, copy at

Ex. 7. "The 1900 official literacy test continued to be freely

applied for 60 years in a variety of forms Ehat effectively

disenfranchised most blacks." Gingles, supra, slip op. at 27;

see Bazemore v. Bertie Countv Board of Elections, 254 N.C.

389 (1961).

Consequently, in November L964, prior to passage of

the Voting Rights Act, which barred use of literacy tests in

in jurisdictions covered by Section 5 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. L973c,

42 U.S.C. 1973b, blacks constituted only L9.7 percent of

Halifax County's registered voEers (4,487 "non-whites" out of

a total of 22,808). Ex. 8A.

In I'tay L964, the federal distrlcc court found that

Halifax Cor:nEy election officials "have been engaglng and

continue to engag,e in a course of conduct which discrirninatorily

deprives Negroes in Halifax county, North carolina, of an

opporCunity Eo regisEer to vote." Alston v. Butts, C.A. No.

875 (E.D.N.C. Temporary Restraining Order, May 8, L964). Ex. 9.

d

-10

The order barred defendants from engaging in dilatory tactics

when registering black voters and required weekday registratlon

through May 16, aE places other than the registrar's residence.

On May L4, L964, the court granted a preliminary lnjunction

in which some particulars of the earlier order \rere modified. S/

rb id.

Black citizens in Halifax County who engaged in political

activity were subjecEed to intimidation and retaliation. A

black Eeacher in the Halifax County school systeno \ras unlaw-

fully fired in L964 for her participation in civil rights

activity, including "voter registraEion and votlng acEiviEy."

Johnson v. Brergtr_ 364 F.2d L77, 178 (4th Cir. 1966), cert.

denied, 385 U.S. 1003 (1967).

In addiEion, prior to L970, the time for voter

registration was limited to a few weeks prior to an election.

Halifax County did noE adopE full-tirne registration until

August 1970. Ex. 5, Ans. to U.S. Interr- Nos. 6 and 7, at 5.

Moreover, black citizens historically have been denied the

opporttrniEy to serve aS elecEion or voter reglstration

officials. Defendants have failed to identify one black Person

who served as an election official before 1970. Ex. 5, Ans.

to U.S. Interr. No. 16, at 10. From L970 until 1983, only Eoken

The injunction was dissolved on May 26, L964. Ex. 9.q

-11

numbers of blacks served

at 10. In L97A, only one

of 85 election officials.

blacks (8.97") of the LL2

Ibid.

as election officials. Ex. 11; Ex. 3,

black person served out of a total

As late as 1980, there were only 10

election officials in Halifax County.

The legacy of this history of voting discrimination

against blacks is that as of L982, when the last county commis-

sioner elections were.held, the black voter registration rate

was 52.3 percent, compared to the white voter registration

raEe of 68.5 percenE, Ex. 4, App. C. Although blacks were

44.5 percenE of Halifax Cor:nty's voting age population in

L982 (17,375 out of 39,044), they vrere only 38.5 percent of

its registered voters (9,082 out of 23,587). Ibid. 9/

Halifax Cor:nty also used voting mechanlsms designed co

dilute potential black voting strength. See Gingles, g.gplg,

slip op. at 28. In f955, the state legislature passed an

anti-single shot voting law applicable to primaries helt in

;

Halif,ax County for county and municipal off ices. 1955

N.C. Sess. Laws 1104, copY at Ex. 7. This law had "the

intended effect of fragmenting a black minority's total vote

between two or more candidates in a multi-seat electi-on and

preventingitsconcentrationononecandidate.''.@,

-supra, slip op. at 28. A black citizen of Halifax

marked increase in the number of registered

Toters -- both among whites and blacks since L982. The

1984 voter registraEion statistics show that the white

registration iat. is 76.8 percent, whereas the black registratlon

raEe is 68.3 percent. Ex. 4, APP. C.

-L2

Councy $ras unsuccessful in his attempt to challenge the law

in scate court. [Jalker v. Moss,246 N.C. 196, 97 S.E.2d 836

(1957). In f 959, the anti-single shot provision was exrended

to general elect?ions for municipalities in Halifax Councy,

L959 N.C. Sess. Laws 906, copy at Ex. 7. A numbered seat

plan for the state representative districE, which included

Halifax County, passed in 1967 and served to prevenE single-

shoE voting. The anti-single shot laws and numbered-seat

provision \.rere used until they were declared unconstituEional

in DunsEon V. Scott,336 F. Supp.206 (E.D. N.C. L972).

See Gingles, supra, slip op. at 28.

In 1960, the method of electing county commissioners

in Halifax changed from a district nomination sysEem to an at-

large nominaEion and election sysEem. 1959 N.C. Sess. Laws

1041. See discussion, ggpgg., at 6-7. This change ensured

that Che white voting majority in the county would be able to

conErol the election for all county commissioners. In 1980,

four of the five districts had black majoritles tn voting age

population. Ex. 3, at 4. B|acks \^rere a rninority of the over-

all county's voting age population. Ibid.

Not one black person has been elected Eo the Halifax

county Board of county commissioners in Ehis century.

Ex. 5, Ans. to Johnson Interr. No. 6, at 4' Nor have

been elected Eo any countywide office in Ehis century.

blacks

Affidavi ts

H.of Harry Watson, Thomas H. Cofie1d, Joe P. lloody, JeEtie

D. Racial Bloc Voting in Contests for Cou4ty Commissioner

-t3

Purnell. LO/ Black candidates have run for county commissioner

eight Eimes from 1968 through L982. L]-/ Ex. 4, App. B. Dr.

A1lan J. Lithtman, a professor of history at the American

University, has analyzed these contesEs to determine whether

voting has been racially polarLzed. Ex. 4. He concludes

thac "Ehe results of analysis demonstrate a substantial and

enduring pattern of racial bloc voting in elections for the

county commissioners of Halifax County, North Carolina."

Ex. 4, at L7. !

Dr. Lichtman's analysis shows thaE in the eight contests

between black and vrhite candidates, on average 90 percent of

the white voters supported the white candidate, while 75

percent of the black voters supported the black candidate.

Ex. 4, at 6-7, L7, APp. E. The following chart shows the

extent of racial bloc voting in the lasE four conCests

between black and white candidates.

7" OF BI.ACKS % OF WHITES

VOTING FOR THE VOTING FOR

YEAR AND CONTEST BI^A.CK CANDIDATE WHITE CANDIDATES

L97 6

DEErict 3

I

, L978

DEricc I

1980

DIErict 4

L982

DllEr ict 1

97

88

82

83

92

88

74

83

ere filed by the Johnson plaintiffs '

LLI Copies of the election returns for c99n!l-cogmissioner

Ef""rioirs from ig6O- ihrougtr 1982 are compiled in Exhibit 10'

-L4

source: Ex- 4, App. E. rn the last four contests, brack

voters' support for the black candidates averaged 86 percent,

while white voters' support for the whice candidates averaged

.t

86 percent. Each of the eight contests between black and

white candidaEes produced an extremely high correlation

between the percentage of blacks among voters in a precincc

and the percenEage of voEers voting for Ehe black candidate.

Ex. 4, at 8-10, epp. n. Each correlation is statistically

signifi.cant -- the results obtained are likely to occur by

chance less than one in one hundred thousand times. Ibid.

Dr. Lichtman also analyzed raclal differences in

voter reglstration from 1968 through 1984, and turnout in all

county commissioher elections from 1968 through L982.

Ex. 4, at II-17, Apps. G and H. Throughout the entire

period the proportion of voting age whites registered to

vote has been higher than the proportion of voting age

blacks registered Eo vote. There are differences in

Eerms of turrrout, as well. On average, black voters

turnout at a higher rate (43.67") in elections with black

I

candidates than do white voters (35.32). But the mean

whice voter Eurnout in contesEs with only white candidates

(36.52) is higher than the black mean (29.07"). Whi.le Ehe

participaEion of white voters aPpears to be independent of

the race of the candidates, black voter participation

increases dramatically in contesEs with black candidates.

Ibid. ln light of this analysis of voter turrlout, Ehe lack

of success of black candidates cannot be aEtrlbuted to the

apathy of black voters.

- 15

tr The Present Day Socioeconomic Effects of

Racial Discriurination

North Carolina has "a long hisEory . . . of racial

discrimination in pub.lic and private facility uses, education,

employment, housing and health." Gingles, !gpl3, slip op. at

3I. De jure racial segregation existed in virtually all

areas of life. Id. at 3f-34; see Johnson Plaintiffsr Motion

for Judicial Notice.

The public schools in Halifax County remained racially

segreg,ated long after Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483 (1954). The Suprerne Court has described the history of

segreBation as follows:

The schools of Halifax County were

cornpletely segreBated by race until 1965.

In that year, the school board adopted a

freedom-of-choice plan that produced very

1ittle actual desegregation. In the L967-

1968 school year, all of the white students

in the county attended Lhe four cradi-

rionally aIl-white schools, while 977' of

the Negro sEudents attended Ehe L4 tradl-

tionally all-Negro schools. The school-

busing system, used by 907 of the studenEs,

$ras segregated by race, and facultY

desegregation was minimal.

United States v. Scotland Neck Citv Board of Education, 407

U.S. 484, 485-486 (L972). In that case, the Suprerne Court

ruled Ehat the L969 law creating a seParate school sysEem

for ScoEland Neck "would have the effect of lmpeding the

disestablishment of alr. dual school system Ehat extsted in

Halifax County." Id. at 490. The county school dlstrict

-15

first began to implement a unitary school plan in L970. Id.

at 487 n. 3.

Today, of three school syscems in Halifax County,

the Roanoke Rapids schools are overwhelmingly white, while the

Halifax County schools and the Weldon schools are overwhelningly

black. L2/ In addition, 18,6 percenE of the white students

attend private schools, compared to only 0.9 percent of the

black students. Ex. 3, at 6.

The present-day effects of chis history of segregated

and inferior schools is Ehat among, the county's population,

25 years and older, there are great disparities in educational

attainrnent betwetn whites and blacks. For examPle, only 57

percent of the blacks had at least an eighCh grade education,

while fully 80,7 percenE of the whites had Ehat much schooling.

Whereas 54.6 percent of the whiCes had completed high school,

only 25.9 percent of the blacks had completed high school.

The median years of schooling for blacks is 8.8, 3.3 years

less than the median years of schooling for whites.

Ex. 3, at 6.

In regard to emPloYment, trro

employers, J.P. Stevens L3/ and the

Company 14/ have been found to have

of the county's major

former Albernarle PaPer

engaged in racial

a2/ See Summary ot

6ry l1B, filed bY

DEEffil6es' Answer Eo Johnson Interroga-

Johnson plaintiffs.

t3/ sledee v. J. P. Stevens, l0 E.P.D. 110,585 (E.D.N.C. 1975)

G;py.pffi-dedE6-@-TIiintiffs'Appen9i*-"f'U}::pgI::d^,-o""i-"ioni), ^if 'd E-, rev'd in parl, 585 F.2d 625 (4Eh Cir'

1978), cert. denied,

L4l Albemarle Paper co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

-L7

discrimination in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq. See

Affidavit of Harry Wat'son. In L979, blacks had a mean family

income of LO,465, only 55 percent of the mean income for

white families. Blacks were four times more likely Ehan

whites to be living in poverty. Ttrey had a higher r:nemployment

rate and those blacks who were employed tended to hold low-

paying, low-level jobs. Consequently, Ehe 1980 Census shows that

Ehe Iiving conditions of blacks in Halifax County were worse

than Ehose of whites. Ex. 3, at 7-9.

II I . ARGT'MENT

The court of appeals has adopted a balance-of-hardship

Eest for interlocutory relief. North Carolina State Ports

AuthoriEy v. Dart Containerline Co. Ltd., 592 F.2d 749 (4th

Cir. L979); Fort Sumter Totllgr-jns. v. Andrews, 564 F.2d 1I9

(4th Cir. L977); Blackwelder Furniture Co. v. SeliP Manufacturtng

Co., 550 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. L977). The four factors to be

considered are: (f) likelihood of success on the merits, (2)

possible irreparable injury to plainEiff if relief is denied,

(3) possible harm to defendanEs if relief is granted, and (4)

the public interest. Ibid. In North Carolina State Ports

Authoritv, supra, 592 F.2d at 75O, Ehe court summarized the

interplay of these four factors, as follows:

There is a correlation between the

Iikelihood of plaintiff's success and

the probability of irreparable injury

to him. If the likelihood of success

-18

is great, the need for showing the

probabiliry of irreparable harm is

less. Conversely, Lf the likelihood

of success is remote, Ehere must be

a strong showing of the probability of

irreparible injury to justify issuance of

the -injunction. Of all the factors, Ehe

two most important are those of probable

irreparable injury to the plaintiff if

an injr:nction is noE issued and likely

harm to the defendanE if an injunction

is issued. If , uPon weighing them, Ehe

balance is struck in favor of plaintiff,

a preliminary injr:nction should issue if ,

at leasE, grave or serious questions are

presen ted.

We submiE Ehat the ltkelihood of success is great on

our claim Ehat defendants t at-large method of electing county

commissioners violates Section 2 and therefore there would be

irreparable injury if black voters were once again denied an

eqr13l opportuniEy as white voters to elect county commissioners

of their choice. Defendants may not use the at-Iarge election

system in effect since L972, Chapter 681, because the Attorney

General has inEerposed a timely Section 5 objection to

thar system and Ehe defendants have not obtained preclearance

from the District court for the District of colurnbia.

Consequently, defendants derive no equitable benefit from the

{status guo, for they admit, correcEly, that Ehe status quo

violates Section 5. A court order requiring elections in

f984 under a lawful system would noE harm defendanEs and the

public interest in ensuring that the votes of black citizens

are noc diluted clearly would be served'

-19

A. There Is a SubsEancial Likelihood Thar Halifax

Cor.rnty's At-Large Election System Violates

Section 2 of Ehe Voting Rights Act, As Amended,

And That Use of That System Will Result In

Irreparable Injury

Congress' primary objective ln amending Section 2

was Eo provide a remedy for racial vote dilution that is not

necessarily the product of inEenEional racial discriminaEion. 14l

While a voting practice that was adopted or has been naintained

for racially discriminaEory reasons would violate Section 2,

a voting practice thaE 'iresults" in racial vote dilution also

a in L982, provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

Eo voting or standard, pracEice, or procedure shall

be imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a

denial or abridgemenE of the right of any citizen

of the United States Eo vote on account of race

or color, oE in contraventlon of the guarantees

set forch in section 4(f) (2), &s provided in

subsection (b).

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is established

if, based on the cotality of circumstances, ic is

shown Ehat the political Processes leading to

nomination or election in the State or political

subdivision are not equally oPen to participation

by members of a class of citizens protected by

subseccion (a) in that its members have less

opportunity Ehan other members of the elecEorate

to- parEicipaEe in the political Process and to

elett representatives of their choice. The extent

to which- members of a protected class have been

elected to office in the StaEe or political sub-

division is one clrcumstance which may be consldered:

Provided, That noEhing in -this section establishes

a-:@Fio have rnembeis of a proteeEed class elected

in nlubers equal to their proporEion in the population.

42 U.S.C. L973. '

-20

would viorate section 2, regardress of the intent of Ehe

defendants. L5/ S. Rep. No. 4L7, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. L6,

p. 27, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong. and Ad. News L77.

The "results" test focuses judicial inquiry on objective

factors concerrling the "totality of circumstances" bearing on

Ehe present abiliEy of minorities effectively to participate

in the political process. The Eest is based upon the standards

developed in Whice v. Regester , 4L2 U.S. 755 (1973) and

subsequent cases, including Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d

L297 (5th Cir. L973) (en banc), aff'd on other grounds sub

ooIIl . East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

636 (1976). S. Rep. No. 4L7 ax 27-30,32; see United States v.

I,larengo Countv Commission, C.A. No. 8L-7796 (lIEh Cir. May L4,

l-984) L6l; Jones v. Citv of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364 (5th

Cir. f984); Gingles, !-yprg.

The Senate Report identifies the following factors as

relevant to the Section 2 "toEality of circumstances" lnquiry:

l. the extent of any history of

official discrimination in the state

or poliEical subdivision that touched

the right of the members of the minority

"intent" requirement is a constitutional

Ixercise of congressional Po$rer to enforce Ehe FourteenEh and

Fifteenth Amendments. United States V. Marengo County-tsmniltion,

c.A. No. 8:..tis6-iirin er;@re84

Johnson Plaintiffts Appendix of unreported Decisions), JE ,.

eTEfrlF lubbock, 727 i-.zd 364 (5th cir. 1984).

L6l A copy is included in Johnson Plai-ntif f s' Appendix of

G-reported Decisions.

-2r

Sroup to register, to vote, oE otherwise to

participate in the democratic process;

2. the extent to which voting in the

elections of the state or political sub-

division is racially polarLzed;

3. Ehe extenE to which the state or

political subdivision has used unusually large

election districts, majority vote requirements,

anti-single shot provisions, or other voting

practices or Procedures that may enhance the

opportunlty for discrimination against the

minoriEy grouP;

4. if there is a candidate slacing process,

whether the members of the minority group have

been denied access to thac Process;

5. the exEent to which members of the minority

group in the state or poliEical subdivislon bear

Etre ef fects of discrimination in such areas '

as education, employmenE and health, which hinder

rheir ability ro- participaEe effectively in the

political Process;

6, whether political campaigns have been

characterLzed by overt or subEle racial appeals;

7. the extenE co which members of the

minority group have been elected to public office

in the jurisdiction-

S. Rep. No. 4L7 at 28-29 (footnotes onitted)'

congress did not intend these facEors "to be used t I

as a mechanical 'point counting' device." S. Rep. No. 4L7, -W.,

at*9, n. ll8. Nor is Ehere a requiremenE "that any particular

number of factors be proved, of that a majoriEy of them point

one $ray or the ogher." Id. at 29. Rather, evidence about

Chese and other relevant factors is intended as a guide for

the court's exercise of its judgmenE about whether "the electoral

-22

system, in tight of its present effects and hisEorical context,

treats mlnorities so unfairly that they effectively lose

access to the political processes." Jones, ggpll, 727 F.2d

at 384-385, see United States v. Marengo, ElEISi Gingles,

supra.

The "EoEality of circumstances" demonstrate thaE

defendants I aE-large county commissioner election system

deprives Halifax County's black citizens of an equal opPortunity

to participate in the political Process and elect counEy

commissioners of their choice. Blacks in Halifax County and

North Carolina have been subjected to a long history of

official racial discrimination concerning their right to vote

and participate in Ehe political process. In L964, the

legacy of the poll tax and Lhe liCeracy tests was reflected

in the facE that Halifax Cor:nty blacks comprised less than 20

percent of the registered voters. Ex. 8. llalifax County

did not institute ful1-time voter registration gntil 1970,

and blacks were noE selected to serve as registration or

election officials in any more than token numbers before

1983. L7l Ex. 3 at 10. ln L982, there was still a sizeable

, the court noted the signifi-

6n "" ofmA"-t=-m-f PoTffi

By hotding shorc hours the Board made it harder

for *ri"gi"tered voters, more of whom are black

Ehan ,hi;i, to register ...' gy lqyiTg-few

black po11'officiits ..' county-officials

impairld black access tg tlt" political system

and the eonfidence of blacks in the system's

oPenness.

Slip op. at 3L42.

-23

disparity beE$reen the black regisEration rate (52.37.) and the

whice registration rate (68.57"). Although abouE 3,000 blacks

have registered since L982, Ehe black registration rate (68.32)

stiII remains significantly lower than the white registration

rate (76.8%). Ex.4, App. C.

Black political participation is also impaired by Ehe

present day socioeconomic effects resulting from racial

discriminaEion in education, employment and other areas. See

supra, at 15-17. Compared to whites in Halifax Cor:nty, blacks

have lower educational, employnent and income levels, and

disproportionately more blacks Iive in poverty and have less

adequate housing. Ex. 3, at 6-9. In amending SecEion 2,

Congress recognized that "[w]here these conditions are shown,

and where the level of black participation in politics is

depressed, plaintiffs need not Prove any further causal nexus

between Eheir disparate socioeconomic status and the depressed

Ievel of political participation." S. ReP- No- 97-4L7, !-g2ra.,

at 29 n. 114; see Gingles, supra, slip oP. at 36 n. 23.

Black candidates have been unsuccessful in their

atEempts to gain election to Ehe Halifax County Board of

County Commissioners. Not one black candidate has been elected

to the county commission or any other county-wide office

in this century. Ex. 5, Ans. to Johnson Interr. No.6, at 4;

Affidavits of Watson, Cofield, Moore and Purnell. The evidence

-24

shows that racial bloc voting ln the eight contests between

black and white candidates between 1968 and L982 is persistent

and severe. Ex. 4. In the last four contesEs, the mean

white support for the white candidaEes was 86 percent, while

the mean black support for the black,candidates was 86 percent.

In other words, only 14 percenE of the whites voted for the

black candidates; similarly, only 14 pecent of Ehe blacks

voted for Ehe white candidates. Ex. 3, App. E.

Evidence of racially polarlzed voting is at Ehe root

of a racial vote dilution claim because it demonsErates that

racial considerations predominaEe in elections and cause the

defeat of minority candidaLes or candidates identlfied wiEh

minority inceresEs. United States v. Marengo, lgPra, slip

op. at 3L37-3138; Jones, supra, 727 F.2d at 384, Gingles,

.supm., slip op. at L6-L7. The three-judge court in Gingles

described the essence of a vote dilution c'lain as follows:

Slip op. at

an at-large

primarily because of the interaction of

substantial and persisEent racial polarizatlon

in voting patterns (racial bloc voting)_with a

challenged- electoral meehanism, a racial mlnority

with distinctive SrouP interests that are ^c-aPa!l"-of aid or amelioration by government is effectively

denied the poliEical Power to further those

interests that numbers alone would PresumPtively

[citation omitted] give it in a voting consti-

iuency noE racially polarLzed in lts voting

behavior.

16. In other words, absent racial bloc voting

system would noE ensure Ehe consistenC defeat of

-25

minoriry candidates or candidates associated with minority

interests. L8/

Halifax County's at-large election system also has

several so-called "enhancing" feaEures that make ic more

dif f iculL for blacks to elect county cornmissioners of Eheir

choice. The county is geographically large, the use of

residency disEricts, which operate like numbered-post

requirements, precludes single-shoE voting, and a majority-

vote requirement applies in primary elections. See United

States v. Marengo, !!pra, slip op. at 3L42; Gingles, !-gpla,

slip op. at 36-38.

Thus in evaluating the Eotality of factual circum'stances

it should be emphaiszed that Ehis lawsuit does not challenge

at-Iarge elections per se. Rather the lawsuit challenges an

elecEion system Ehat has been used succestf"lly for many

years to preclude black citizens from effectively parEicipatlng

in the political process. The election structure challenged

is imposed in the context of a long history of racial

discrimination with present day effects and is imposed also

I barriers to registraEion, voting

anA candidacy may no longer exisE does noE eliminate the

violation because racial bloc voting coupled with other

factors may still deny minorities equal opportunllY in an at-

iirg" eleciion system. See Jones, iupra,- 127 F.2d ac 384-

385; Gingles, su-pra, slip op-716]-

-26

in the context of undisputable evidence of racial bloc voting.

The election structure contains at-large provisions, as well

as a majority vote requiremenE and residency districts, which

preclude single-shoE voting, all of which, in chese

circumstances, hinder effective minority participation.

The evidence also supports a finding that the aE-large election

system has been maintained to date for the PurPose of

,minimizLng the voting strength of black citizens of Halifax

County. -BggeIS_ r. Loc!gs., 458 U.S . 613 (1982) .

These factors, considered in their totality, make

iE exceedingly likely that the United Scates will prevail

on its claim that the defendants' at-large cotrnty commis-

sioner election system violates Section 2. The court of

appeals has recognized that "[i]f the likelihood of

success is greaE, Ehe need for showing Ehe probability of

irreparable harm is less." North Carolina State Ports

Authority, supra , 592 F.2d ac 750. llere , however, the

-----_f'_

black ciEizens of t{alifax County will suffer irreparable

harm if, once again, they are unable Eo have an equal

opportunity to elect county commissioners of Cheir choice.

Since 1968, county commissioner elections admittedly have

been held in violation of section 5, as Ehe defendanEs

implemenced voting changes without obtaining preclearance

-27

under the Act. The six-member election plan failed to satisfy

the section 5 substantive standard and the racial discrimination

which occurred as a result of iEs unlawful implementation for

so many years cdnnot be repaired fully. rt is crear, however,

that further injury to black cicizens of Harifax county wirl

result if brack citizens are required to suffer under another

at-large election in the context of the terms described above.

The 1984 erections should be held under a system that both

complies with section 5 and Section 2 of the Act, if irreparable

injury is to be avoided. L9/

B. Defendants l^Iill NoE Be Harmed By the rssuance ofAn In iunction

Defendants have an interesL in holding county commisisoner

elections this year under a lawful system. They recognize

that they may noE hord county commissioner elections this

year under the existing, six-member, 3t-large election system

adopted in L97L, chapter 681, because the Attorney General

hat interposed a timely objection under section 5 to the

implt-'mentation of that system. Although defendants now seek

Section 5 preclearance from the District Court for the District

of colurnbia, they have agreed to Ehe issuance of a permanent

injunction against use of the chapter 681 system, unless and

L9l Additionally, when, as hEie, the AUtorney General is

a[chorLzed ro seLk preliminary relief, 42 U.S:C. 1973j(d),

and the facts presented establish a prima facie violafion,

the Attorney General "is not requireffi-shtilfrreparable'

injury before obtaining an injuncEion." UniEed States v.

Haves Int'l Corp.,4L5 F.2d 1038, 1045 (5m9'). The

ffiirreparable injury should be presumed.from

the very fact that the statute has been violated." Ibid,

_28

until preclearance is obtained. 20l Defendants' l"lotion to

Dissolve Three-Judge court. consequently, if elections are

to be held this yeat, the status quo will have to be altered'

Reversion to the system in effect prior to the

implementation of chapter 68I the course defendants aPPear

toprefer..wouldrequireanewcandidatequalification

period, new prirnary dates and a determination about how to

decrease the county commission from six to five members' see

Submission for Che United States on Relief for Defendantsr

violation of Section 5 of the voting Rights Act' Defendants

therefore would noE be harmed by a court-ordered, lnEerim plan

because such a plan would require a new candidate qualification

periodandnewprimarydates.Anewelectionschedulewill

be required in any event. Ltoreover, a court-ordered, interim

plan could allow defendants Eo mainEain a six-member county

commission. -t

Inearlierpleadings,defendantsassertedEhatit

would be unconstitutional to use the five-member, at-large

electionsystembecausethefiveresidencydistrictsare

ience in Section 5 declaratorY

Jfdgmenr actions, ir ii "ot"fit"fy

chat the court would be in

a posirion t"-".i i; rime-ior chi; y""i'" election' Defendants

have not asserted otherwise'

-29

malapportioned. Defendants' I"temorandum in Support of Motion

for Preliminary Injunction, 3t 2-3. The Supreme Court has,

however, ruled that malapportioned residency disCricts in

at-large elections systems do not violate the Fourteenth

Amendment. Dallas County v. Reese, 421 U.S. 477 (1975);

Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S. LL2 (L967). But defendants legitimately

may prefer to have properly apPortioned residency districts '

A court-ordered plan could serve that interest, whereas use

of the five-member system could not.

Finally, w€ believe that this court could adopt an

inrerim plan with minimal additional disruption of Ehe

electoral process, for it is Possible to adopt a single-member

district plan, wiEh six county commissionerg, based largely

on the existing residency districts, wiEh little, if anY,

alteration of precinct 1ines. See Johnson Plaintiffs' I"lemorandum

In Support of Motion For Preliminary Injunction, at 30-31'

C.ThePublicInEeresEWouldBeServedByThe

Issuance Of An InjuncllPg

congress established thaE the public interest requires

that election systems that r:nlawfully dilute black voting

strength not be used, 42 U'S'C' Lg73' and authorized the

Attorney General to seek prelinlnary relief to Prevent a

violation of the Voting Rights Act' 42 U'S'C' 1973j(d)'

The public interest would Eherefore be served if black citizens

are afforded an equal oPportunity to elect county comrnissioners

of their choice.

-30

IV. THE INJUNCTION

We request Ehat this Court enjoin county commissioner

elections in L984 under the only at-large election system

defendants may use trnder Section 5 the syst.em in effect

prior Eo the implementation of Chapter 68I. In order that

county commissioner elections may be held this year, w€ seek,

in additlon, a mandatory injunction requiring elections under

a court-ordered, interim plan.

The interim plan should include a new candidatL

qualification period and establish a date for a primary

election. In establishing an election schedule, recognition

should be given to Ehe fact that at least since 1960, Ehe

Democratic nomination has assured election; noE one Democratic

nominee has been challenged in the general election during

that period. Ex. 10. This fact suggests that the length of

the campaign period between candidate qualificaEion and the

primary is more crucial than the time beEween the primary and

Ehe general election.

Upon finding that an election system is unlawful, a

district court ordinarily should allow the defendant an

opportuniEy to propose a lawful plan. lJise v. Lipscornb, 437

U.S. 535, 540 (1978); Jones, 9.11p5e., 727 F.2d aE 387; Ginsles,

supra, slip op. at 69-7L. Because of the Eime, w€ submit

- 3l

that this Court should adopt an interim plan to be used in

the event defendants fail co propose within ten days of the

issuance of the injunction an alternacive plan. Defendants'

proposal, if precleared under Section 5, FlcDaniel v. Sanchez,

452 U.S. 130 (1981), would then be ordered into effect in

place of Ehe court's plan provided Ehe court determines it is

satisfactory. In these circumstances, the AtEorney General

would be prepared to review a complete submisslon on an

expedited basis.

V. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should enjoin

county commissioner elections under the at-large election

system and require elections to be held this year under a

court-ordered, interim plan.

Dated this Jl\ a^y ot June,

SAMUEL T. CURRIN

United Srates AEEorney

r984

Respectfully subrnitted,

W},I. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

Assi-sEant Attorney General

STEVEN H. ROSENBATIM

POLI A. MARI"IOLEJOS

Attorneys, Voting Section

CiviI Rights Division

DeparEmenE of Justice

l0th & Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W

Washington, D. C. 20530

(202) 272-6295

PAUL F. HANCOCK

-\

t

IN THE UNITED STATES COT]RT OF APPEALS

FOR TI{E FIFT}T CIRCUIT

No.75-3707

No.76-1638

ITNITSD STATES OIT AT4ERIG,

Plaintlff-Appellanr ,

v.

THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF !'ORREST COU}TIY,

I.lISSISSIPPI, €r a1. r

Defendant s -Appe l_ lees .

On Appeal from the United SEates District Court

for the Southern District of Mlsslssippl

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

ROBER? E. HAUBERG

Unlted States Attorney

J. STAM,EY POTTII{GEJI

Asslstant Attorney Generai.

BRIAN K. iAi{i'SBERc

JESSIC{ DUI\SAY SILVEfr,

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington. D.C. 20530

-37 -

-./

.,Therelsnoquestionthatblacks-inForrestCounty

have been deprlved of thelr normal votLng strength' Wtrere

black voters are geographLcally concentrated, the nodel

for determlning whether potentlal voting strength is

diminished ib Itthe number of seats on the board of super-

vLsors prop6rtionate to thst populationti percentage of

the whole.rt &1r}E9z, v. Board of Supervisors of Htnds Countvt

528 F .2d 536, 543 (5ttr Cir. L976), IsEgEl;gE sranted'

-F.2d

-

(Ilay 12, Lg76); Sgg @ v. Unlted States, 44 U'S'L'!I'

at 4437 1. 8 (ma3ority oplnLon;LE'l aad 4443 (Marsha11, J.,

dlssenting). Btacks eomprise approximately 251" of the Popu-

lation of Forrest couney and are geographlcally concentrated

tn four cLusters tn a relatively sma11 area of the cotrnty.

Thus, lf able to realize their normal votlng strength btacks

would eLect 257. or 1 .25, - of the members of the flve-nember

Board. E Kirks.ey v. Board of suPervl-sors of llinds countY.,

528 F.2d at 542; @ v. unLted states, 44 U.S.L.W. at 4437

o. 8. The current reapportionment plan fragments the strb-

L 7 I In Ee"I, blacks constituted 357" of the regLstered voters

Iilttero OGns. The Supreme Court noted that they had a

',ttreoretical

-pot"iiiaf

tt electLng L.7 of the five councllueu.tt

44 IJ.S.L.W. ^t

tr+zt fr. 8. cOncludLng that under the redis-

trtcting plan in question ttaE least one and perhaps. two l'iegro

.o"".iiiur,t' could be electedr .&.!9. r the Court upheld the con-

stiEutionalltY of the Plano

4

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE,

I hereby certify that I have this day served the

foregoing Brief for the United SEates on the parties to

thLs case by oaillng two copies to their.counsel, fLrst

class postage prepaLd, at the address listed below:

R. W. Ileidelberg

D. Gary Sutherland

Jaoes F. llcKenzie

Ileidelb€tB r Sutherland and llcKenzie

P.O. Box 1070

EattiesburBr MississiPPi 39401

This 26tln day of MaY , 1976.

-LsxA br,*q {r1""+

JESSICA DUNSA$JSILVER

Attorney

Department of JusEice

Washington, D.C. 20530

DOJ-197648