Plaintiffs' Request for Admissions

Public Court Documents

February 3, 1986

28 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Request for Admissions, 1986. 59b101ba-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/9f976ef6-3783-4bc1-a49d-7b8cf47d3421/plaintiffs-request-for-admissions. Accessed February 16, 2026.

Copied!

| by eb6 * » te

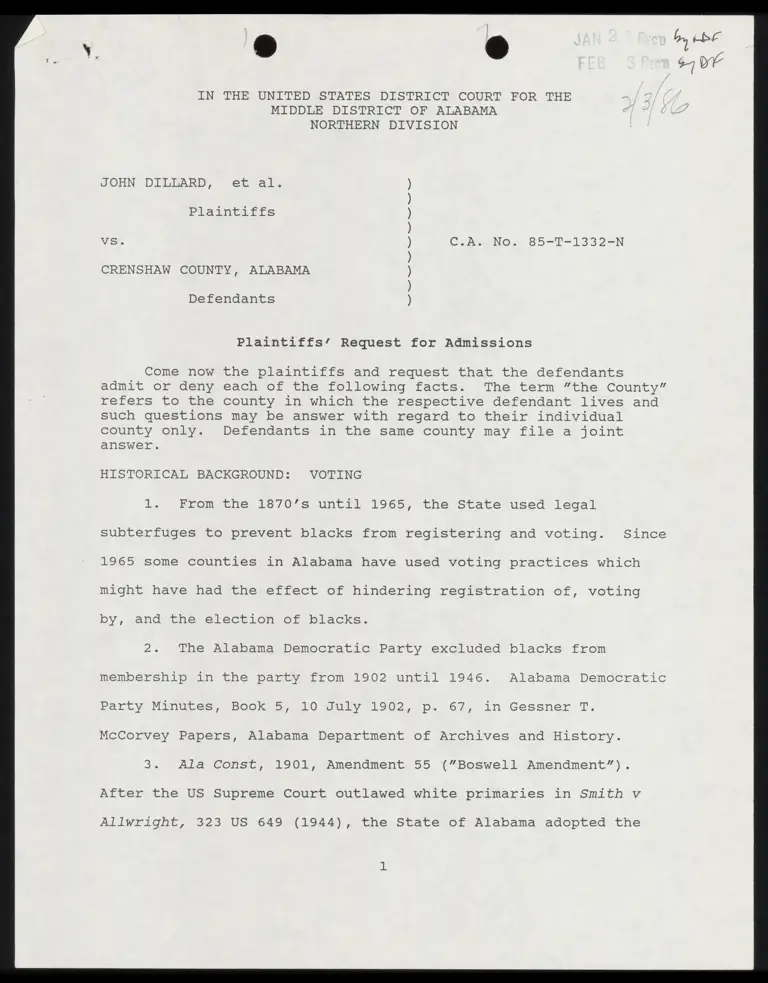

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD, et al.

Plaintiffs

vs. C.A. No. 85-T-1332-N

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA

V

a

”

N

a

”

N

s

”

S

a

s

?

N

a

’

N

t

”

N

a

t

”

N

u

?

u

s

t

”

Defendants

Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

Come now the plaintiffs and request that the defendants

admit or deny each of the following facts. The term “the County”

refers to the county in which the respective defendant lives and

such questions may be answer with regard to their individual

county only. Defendants in the same county may file a joint

answer.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: VOTING

l. From the 1870’s until 1965, the State used legal

subterfuges to prevent blacks from registering and voting. Since

1965 some counties in Alabama have used voting practices which

might have had the effect of hindering registration of, voting

by, and the election of blacks.

2. The Alabama Democratic Party excluded blacks from

membership in the party from 1902 until 1946. Alabama Democratic

Party Minutes, Book 5, 10 July 1902, p. 67, in Gessner T.

McCorvey Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

3. Ala Const, 1901, Amendment 55 (“Boswell Amendment”).

After the US Supreme Court outlawed white primaries in Smith v

Allwright, 323 US 649 (1944), the State of Alabama adopted the

Boswell Amendment which provided for the elimination of the

exemption to the literacy test for those who owned personal

property assessed at $300 or more and the enhancement of the

literacy test with the requirement of demonstrating a

satisfactory understanding of a section of the Constitution of

the United States.

4. Davis v Schnell, 81 FSupp 872 (SD Ala 1949) (three-judge

court), aff’d 336 US 932 (1950), enjoined the enforcement of the

Boswell Amendment. The three-judge federal district court noted

that during the time the Boswell Amendment had been in effect the

Mobile County Board of Registrars had registered 2800 whites

without asking them to explain the Constitution while registering

65 blacks and rejecting 57. The court concluded that the

Amendment “was intended to be and is being used for the purpose

of discriminating against applicants for the franchise on the

basis of race or color.”

5. Ala Const, Amend. 91 (adopted in 1951), allowed

registration only of those who could read and write any article

of the U.S. Constitution, were of “good character,” and

"understood the duties and obligations of citizenship.” Boards

of registrars were declared to be judicial officers. Finally,

the state Supreme Court was required to prepare questionnaires to

be used by local registrars. The amendment passed by a margin of

only 60,357 to 59,988,

6. The Alabama Supreme Court promulgated a four-page

questionnaire which required the applicant to write his name ten

times in answer to several questions, explain his business or

employment background three times, answer two different questions

regarding his length of residence in several places, and give his

spouse’s place of birth. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,

Voting: Hearings held in Montgomery, December 8-9, 1958, and

January 9, 1957 (1959), pp. 17-20 reproduces the questionnaire.

7. Ala Laws, 1961 1st Ex.Sess., Act 21, proposed a

constitutional amendment to replace the voter registration

questionnaire with an application and a separate examination,

both of which would be drafted by a state board of voter

registration examiners. The local board of registrars would

determine qualifications to vote from the application, and the

state board would grade the examination knowing only the number

assigned by the county board. The amendment was defeated by a

vote Of 94,281 to 163,847. ADAH, Alabama Official and

Statistical Register 1963, pp. 756-7.

8. Ala Laws, 1963 Reg.Sess., Act 417 proposed a

constitutional amendment, which was identical to the recently

defeated 1961 proposed amendment except that the voter

examination was clearly labeled as a test of intelligence. The

proposal set a minimum intelligence level equal to that required

by the armed forces, but the voter registration examiners could

set it higher. The voters defeated the amendment, 30,819 for and

81,693 against. ADAH, Alabama Official and Statistical Register

1967, . pp. 675-7.

9. Ala Const, Amend. 223 (adopted in 1965), required

applicants for voter registration to demonstrate the ability to

read and write English. The voters approved the amendment by a

margin of 93,647 to 37,137 with a majority in favor in every

county. ADAH, Alabama Official and Statistical Register 1967,

PP. 707-9.

10. Ala Code, tit. 17, $31 (1958, 1973 Supp.) (the

implementing bill accompanying Amendment 223) provided that the

ability to read and write English could be demonstrated by an

eighth grade education, or a state board of education test For

literacy. This was later codified in Ala Code 8174-7 :(1975),

which was repealed by Ala Acts, 1978, No. 584.

11. United States v Alabama, 252 FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966)

(3-Judge court), declared the poll tax unconstitutional on the

grounds that its purpose and effect was to abridge the right to

vote by blacks.

12. At the time of the 1984 primary and general elections,

an injunction issued in Harris v Graddick, CV 84-T-595-N (MD

Ala), governed the appointment of polling officials in the

County.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: SCHOOL SEGREGATION

13. Ala Laws, 1868, p. 148. It is not lawful to unite in

one school colored and white children, unless by unanimous

consent of parents and guardians. Trustees shall in all other

cases provide separate schools. Repealed by Ala. Code, 1923, 811.

14. Ala Laws, 1873, p. 176. « Provided for a "State Normal

School and University” for the Colored Race, for the education of

colored teachers and students. Last codified as Ala Code, 1940 &

1988, tit, 52, §8452~-5., Declared unconstitutional in United

States v Alabama, 252 FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966).

15. Ala Const, 1875, Article XIII, Section 1. Separate

schools shall be provided for the children of citizens of African

descent. Replaced by Ala Const, 1901, §256, which was

subsequently repealed by Amendment 111.

16. Ala Laws, 1876, p. 98, Section 9. Names of poll

taxpayers of colored race are to be kept in separate books.

Amounts paid by persons of colored race shall be devoted to

maintenance of schools for the colored race. Later codified as

Ala Code, 1896, Sections 3607-8; later codified as Ala Code,

1907, §1858. Repealed by Ala Code, 1923, §11.

17. Ala Laws 1878, p. 136. Repeated separate school

requirement of 1875 Const. Later codified as Ala Code, 1907,

Section 1757. Repealed by Ala Code, 1923, §11.

18. Ala Laws, 1884-1885, p. 349. Repeated separate school

provision. This law was never codified.

19. Ala Laws, 1892-3, p. 887. Appropriated a sum annually

to the Tuskegee Institute (deducted from the “general fund for

colored children”) and provide for the appointment by the

governor of 3 commissioners who would also sit as members of the

Board of Trustees. Last codified as Ala Code, 1958, tit. 52,

§455(1) .

20. Ala Code, 1896, Section 3720. Alabama School for Negro

Deaf and Blind established. This school was consolidated with

the white schools for the deaf and blind under Ala School Code,

1927, 8877 and Alas Code, 1940, tit. 52, 8519.

21. Ala Const, 1901, Article XIV, Section 256. Separate

schools shall be provided for white and colored children, and no

child of either race shall be permitted to attend a school of the

other race. Repealed by Amendment 111.

22. «Ala Const, 1901, 3256. State to provide a ”liberal

system of public schools” separate for each race. Repealed by

Amendment 111.

23. Ala Acts, 1911, p. 677. A Reform school for juvenile

Negroes shall be established, at Mt. Meigs, with name “Alabama

Reform School for Juvenile Negro Law-Breakers.” The school shall

have nine trustees, of whom five may be Negro women. The School

replaced the privately-run Reformatory for Negro Boys run by the

State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Later codified as Ala

School Code, 1927, §709-19; Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 52,

§603-13. Repealed by Ala Acts, 1947, p.31l.

24. Ala Acts, 1915, p. 284. Separate lists of white and

Negro children shall be kept in making school census. Repealed

by Ala Code, 1940, tit. 1, §9; the census provisions of Ala Code,

1940, tit. 52, §54 makes no mention of race.

25... Ala Acts, 1919, -p. 567. Created Alabama Boys

Industrial School for whites only. Last codified as Ala Code,

1940 & 1958, tit. 52, §§585 et seq. The constitutionality of

these sections was questioned in United States v Alabama, 252

FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966), and they were repealed by Ala Code, 1975,

$1-1-10.

26. Ala School Code, 1927, §352. Required separate

quarters for white and black applicants taking state teacher

examination. Last codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 52,

§335. The constitutionality of these sections was questioned in

United States v Alabama, 252 FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966), and they

were repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

27. Ala School Code, 1927, §356. Required separate

institutes for white and black teachers. Last codified as Ala

Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 52, §339. All racial language was

eliminated from this section by Ala Code, 1975, §16-23-7.

28. Ala School Code, 1927, §482. Allowed only whites to

enroll at the Alabama School of Trades and Industries. Last

codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 52, §443. Ala Code,

1975, §16-60-211, eliminated all racial language from this

section.

29. Ala School Code, 1927, §510. Admission to Alabama

College at Montevallo restricted to whites. Last codified as Ala

Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 52, §466. Ala Code, 1975, §16-54-11,

eliminated all racial language from this section.

30. Ala Acts, 1931, p. 272. Created State Training School

for Girls for whites only. Last codified as Ala Code, 1940 &

1958, tit. 52, §§570 et seq. Repealed by Ala Code, 1975,

§1-1-10.

31. Ala Acts, 1955, p. 492; reenacted and amended by Ala

Acts, 1957, p. 483. Pupil Placement Act. Allowed local school

board to assign students on the basis of several factors; school

board has no authority to relocate students except after its own

study (apparently to prevent compliance with federal court

orders); child cannot be compelled to attend school where ”the

races are commingled.” Last codified as Ala Code, 1958, tit 52,

§61(1)-(12). Held constitutional on its face, Shuttlesworth v

Birmingham Board of Education, 162 FSupp 372 (ND Ala), aff’d 358

US 101 (1958) (per curiam). Held unconstitutionally applied, Lee

Vv Macon County Board of Education, 231 FSupp 743 (MD Ala 1964).

32. Ala Acts, 1945, p 62. State board of education may

provide financial aids to Alabama residents to attend

out-of-state schools for graduate and professional education not

available at state-supported schools. Last codified as Ala Code,

1975, 8§816-3-32 and 34.

33. Ala Code, 1923, 86226 and Ala Code, 1940, tit. 46, §26,

provided that graduates of the University of Alabama Law School

were entitled to practice law without an examination. No black

graduated from the law school until 1972. The State Supreme

Court held that this section applied only to graduates of the

University of Alabama Law School and not to persons who had

accepted state funds to attend on out-of-state school. Ex parte

Banks, 254 Ala 117, 48 So2d 35 (1950).

34. Ala Acts, 1949, p. 710. State board of education could

contract with Tuskegee Institute and Meharry Medical College to

provide education for Alabama residents. Repealed by Ala Code,

1975, '§1-1-10.

35... “Ala Const, 1901, Amendment 111 (1956, 1st Ex. Sess).

Amended §256 to repeal right to free education. Also provided

that the legislature could authorize parents or guardians of

students to elect to attend one-race schools.

36. Ala Const, 1901, Amendment 112 (1956, 2d Ex. Sess).

Legislature could enact laws allowing alienation, with or without

consideration, of public parks and housing projects.

37. Ala Acts, 1956 24 Ex. Sess., p. 446. Amended the

compulsory school attendance law to provide that parents could

choose whether child would attend one-race school. Last codified

as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit 52, §297. Ala Code, 1975,

§16-28-3, eliminated all racial language from this section.

38. Ala Acts, 1956 24 Spec. Sess., Act 42. Declared the

U.S. Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision to be “null,

void, and of no effect” in Alabama.

39. Ala Acts, 1957, p. 723. Local boards of education may

make final and unreviewable decision to close schools where

continued operation would be accompanied by tension, friction,

ill will, or disorder; board may make payment for private

education if public schools not open; board may make payments for

private education to prevent enrollment of students who would

cause tension, etc; board may sell closed schools to private,

non-profit educational groups. Last codified as Ala Code, 1958,

tit 52, §§61(13)-(19). Repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

40. Ala Acts, 1957, p.827. Established 21 scholarships to

Tuskegee Institute nursing school for black women and men. Last

codified as Ala Code, 1958, tit. 52, §§455(2)-(4). Ala Acts,

1971, No. 2301, eliminated all racial language from this act.

41. Ala Acts, 1961, p.1396. Authorized established of

vocational trade school “for Negroes” at Gadsden. Last codified

as Ala Code, 1958 (1973 Supp.), tit. 52, §451(8).

Constitutionality questioned in United States v Alabama, 252

FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966), and repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

42. Ala Acts, 1965, p.1281. Amended section of Ala Code,

1958, tit. 52, §61(8) (assignment and transfer law) to allow

tuition grants of $185.00 per year for students to attend private

nonsectarian schools. Repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

43. Ala Acts, 1966 Sp. Sess., p.75. Repealing the teacher

tenure laws as applied in Wilcox County and giving the Wilcox

County board of education exclusive and plenary authority to

appoint, transfer, remove, etc, teachers. This act was never

codified and was declared unconstitutional in Alabama State

Teachers Ass’n v Lowndes Co. Board of Education, 289 FSupp 301

(MD Ala 1968).

44. Ala Acts, 1966 Sp. Sess., p.372. "To preserve the

integrity of the local public school systems against unlawful

encroachment [by the federal government] in the administration

and control of local schools,” state appropriations would replace

any federal funds withdrawn by reason of failure to perform “some

10

act not required by law.” Repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

45. Ala Acts, 1967, p.8l1ll. Allowed parents to choose the

race of the teachers of their children; school board to reassign

teachers as necessary; failure of board to follow law would

result in cut off of state funds. Repealed by Ala Code, 1975,

£§1-1-10,

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: HARASSMENT OF NAACP

46. In 1956 the Attorney General of Alabama brought suit to

enjoin the NAACP from operating in Alabama because of its failure

to qualify as a foreign corporation. The Montgomery County

Circuit Court issued an ex parte order restraining the NAACP,

pendente lite, from engaging in further activities within the

State and forbidding it to take any steps to qualify to do

business under Alabama law. When the NAACP attempted to obtain

review of a contempt citation, which it received for willful

failure to produce certain documents, the Alabama Supreme Court

refused to entertain the writ of certiorari and dismissed the

petition. The US Supreme Court held that the State Supreme Court

had jurisdiction to entertain the NAACP’s federal claims. The US

Supreme Court set aside the contempt fine and remanded the case,

holding that the State Supreme Court had applied a “novel

procedural requirement” to avoid hearing the NAACP’s appeal.

NAACP v Alabama, 357 US 449 (1958).

47. The Alabama Supreme Court again affirmed its decision

on the ground that the US Supreme Court was mistaken in its

11

facts. NAACP v Patterson, 268 Ala 531, 109 So2d 138 (1959).

48. The US Supreme Court once again granted certiorari and

remanded the case to the Alabama Court. NAACP v Patterson, 360

US 240 (1959).

49. In 1960, the Montgomery Circuit Court had still refused

to hold a hearing on the NAACP’s motion to dissolve the ex parte

order. The NAACP filed suit in federal court. The US Supreme

Court eventually ordered the US District Court to proceed to

trial if the State court did not accord the NAACP an opportunity

to be heard by 2 January 1962 on its motion to dissolve the 1956

order and on the merits os the action in which such order was

issued. NAACP v Gallion, 368 US 16 (1961), vacating 290 F2d 337

(5th Cir).

50. The Montgomery Circuit Court held a hearing in December

1961 and dissolved a previously issued temporary injunction, but

issued a permanent injunction. The Alabama Supreme Court refused

to consider the merits of the NAACP’s appeal because unrelated

assignments of error were argued together. NAACP v Flowers, 274

Ala 544, 150 So2d 677 (1963). The US Supreme Court held that the

State Supreme Court had never before applied its procedural rules

with such “pointless severity.” The US Supreme Court reached the

merits and found that the State was attempting to suppress the

right of persons to associate in Alabama. The charges the State

had made against the NAACP were essentially that it had

encouraged citizens to assert their constitutional rights and to

protest against segregation. The US Supreme Court reversed and

12

remanded with instructions that the injunction be vacated and the

NAACP allowed to qualify to do business. NAACP v Alabama, 377 US

288 (1964).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: MISCEGENATION

51. Ala:const, 1865, Article IV, Section 31. 1%t shall De

the duty of the general assembly at its next session, and from

time to time thereafter, to enact laws prohibiting the

intermarriage of white with Negro persons, or with persons of

mixed blood, declaring such marriages null and void ab initio,

and fixing penalties. Repealed by Ala Code, 1886, §10, pursuant

to the 1868 Constitution.

52. Ala Penal Code, 1865-66, §61. Marriage, adultery or

fornication between white and a negro (including octaroons)

punished by imprisonment for 2-7 years (cf, adultery or

fornication: up to 2 years on third offense). Later codified as

Ala Code, 1907, Section 7421. Ala Acts, 1927, p. 219, amended

this to white and ”any negro, or the descendant of any negro.”

later. codified in Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 14, §360. Held

unconstitutional in United States v Britain, 319 FSupp 1058 (ND

Ala 1970).

53. Ala Penal Code, 1865-66, §62. Issuance of license or

performing ceremony for interracial marriage punishable by $1000

fine and/or up to 6 months in jail. Last codified as Ala Code,

1940 & 1958, tit. 14, §361. Held unconstitutional in United

States v Britain, 319 FSupp 1058 (ND Ala 1970).

13

54. Ala Const, 1901, Article IV, Section 102. The

legislature shall never pass any law to authorize or legalize any

marriage between any white person and a Negro, or descendant of a

Negro. Held unconstitutional in United States v Britain, 319

FSupp 1058 (ND Ala 1970).

55. The State was still enforcing the anti-miscegenation

statute in the early 1950's. Jackson v State, 37 Ala App 512, 72

S024 114 (Ct Crim App), cert denied 260 Ala 698, 72 So2d 116,

cert denied 348 US 888 (1954). The law was declared

unconstitutional, United States v Britain, 319 FSupp 1058 (ND

Ala 1970).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: TRANSPORTATION SEGREGATION

56. . Ala Laws, 1891, p. 412. All railroads carrying

passengers, other than street railways, shall provide equal but

separate accommodations for the white and colored races, by

providing two or more passenger cars for each passenger train, or

by dividing the passenger cars by partitions so as to secure

separate accommodations. The conductor is to assign each

passenger to his place. If a passenger refuses to occupy it, he

may refuse to carry such passenger on train, and is not liable

for damages. But this section does not apply to white or colored

passengers entering the state upon railroads under contract for

transportation made in other states where like laws to this do

not prevail. A person riding or attempting to ride in wrong

place in railroad coach, is subject to a fine of $100. All

14

railroad companies neglecting to comply with the requirements of

this act within sixty days, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor, and

fined not exceeding $500. Any conductor, etc., neglecting to

carry out the provisions of the acts, is guilty of a misdemeanor,

and may be fined an amount not to exceed $100. Later codified as

Ala Code, 1907, Section 5487, Section 7648; Ala Code, 1940 &

1958, Sections 196-8, 464. Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10 repealed

§§196, 197, and 464. Ala Code, 1975, §37-2-115 eliminated all

racial language from §198.

57. Ala Acts, 1945, p 731. All transportation companies

shall provide “equal but separate accommodations” in stations and

vehicles for white and colored passengers, whether intrastate or

interstate. Fine of up to $500 for violation by company. Last

codified as Ala Code, 1958, tit. 48, §301 (31b). Held

unconstitutional in Browder v Gayle, 142 FSupp 707 (MD Ala 1956)

(3-judge court).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: JURIES, CRIMINAL LAW, AND COURTS

58. Ala Laws, 1865-1866, p. 98. Negroes shall testify only

in open court, and only when a freed man, free Negro, or a

mulatto is a party. Repealed by Ala Code, 1867, §10.

59... Ala Acts, 1876-7, p. 1°20; repealed by Ala Code, 1940,

tit. 1, §9. Replaced the sheriff, probate judge, and circuit

clerk with 5 commissioners appointed by the governor as the body

to compile the list of persons “thought competent” to serve as

jurors. According to Rabinowitz, this act affected 6 counties in

15

the Black Belt with Republican majorities by removing the

selection of jurors from locally elected (Republican) officials

and placing it in the hands of commissioners appointed by the

(Democratic) governor. Rabinowitz, Race Relations in the Urban

South, 1865-1890-(1%78), p.39.

60. Systematic exclusion of blacks from grand and petit

juries was found in Norris v Alabama, 294 US 587 (1935);

Patterson v Alabama, 294 US 600 (1935); Rogers v Alabama, 192 US

226 (1903); Seals v Wiman, 304 F24 53 (5th Cir 1962); Mitchell v

Johnson, 250 FSupp 117 (MD Ala 1966); White v Crook, 251 FSupp

401 (MD Ala 1966) (3-judge court).

61. Noting that of all the black policemen, detectives,

marshals, sheriffs, constables, probation and truant officers in

1930, only 7% were employed in the South, Myrdal says:

The geographic distribution of Negro policemen is in inverse

relation to the percentage of Negroes in the total

population. Mississippi, South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia

and Alabama -- the only states with more than 1/3 Negro

population -- have not one Negro policeman in them, though

they have nearly 2/5 of the total Negro populations of the

nation.

2 Myrdal, An American Dilemma 543 (Pantheon Paperback 1964).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: INSTITUTIONAL SEGREGATION

62.4% Ala Penal Code, 1865-66, $241: Ala Acts, 1911, p. 356;

Ala Code, 1876, §4321. Segregation of black and white jail

inmates. last codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 12 §188;

tit 45, §§121-3, $172, §183. Declared unconstitutional in

Washington v Lee, 263 FSupp 327 (MD Ala 1966).

16

63. Ala Laws, 1876, p. 285. White and Negro prisoners are

not to be confined permanently together in the same apartments

before conviction, if there are enough separate apartments.

Misdemeanor, with a penalty of a fine not less than $50 nor more

than $100. Declared unconstitutional in Washington v Lee, 263

FSupp 327 (MD Ala 19686).

64. Ala Laws, 1884-1885, p. 192. It is unlawful for white

convicts, whether state or county convicts, and colored convicts

to be chained together, or to be allowed to sleep together, or to

be confined in same room or apartment when not at work. Declared

unconstitutional in Washington v Lee, 263 FSupp 327 (MD Ala

1966) .

65. Ala Laws, 1885, p. 187, §19. Provided for segregation

of prison inmates by race. Later codified as Ala Code, 1940 &

1958, tit. 45, §52. Declared unconstitutional in Washington v

Lee, 263 FSupp 327 (MD Ala 1966).

66. Ala Acts, 1923, p. 67. Segregation of black and white

prisoners who were tubercular patients. Later codified as Ala

Code, 1940 &.1988, tit 45, §4.

67. ‘Ala Acts, 1923, p. 738. Segregation of black and white

mental deficient. Last codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit

45, §248. Constitutionality questioned in United States v

Alabama, 252 FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966), and repealed by Ala Code,

1875, 81=1-10.

68. Ala Laws, 1927, p.521. Segregation in county home for

the poor. last codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 44, §10.

17

Constitutionality questioned in United States v Alabama, 252

FSupp 95 (MD Ala 1966), and repealed by Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

69. ‘Ala Acts, 1931, p. 166, Segregation of black and white

prison inmates. Last codified as Ala Code, 1958, tit 45, §52.

Declared unconstitutional in Washington v Lee, 263 FSupp 327 (MD

Ala 1966).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: ASSOCIATIONAL SEGREGATION

70. Myrdal observed the following about professional and

business contacts between the races:

Voluntary associations -- civic, social, business, and

professional -- almost always prohibit Negro members in the

South *** unless the association is concerned with some

phase of the Negro problem. They simply refuse to invite

Negroes to membership or to admit them when they apply for

membership, whether by formal policy or by informal ad hoc

action of the membership committee. #*** The professional

associations, such as the state bar and medical societies,

usually admit Negro members in the North but not in the

South. **x%

[T]rade unions *** exclude or segregate Negroes.

Because of their exclusion from the various

associations, Negroes have formed their own associations.

2 Myrdal, An American Dilemma 638-39 (Pantheon Paperback 1964).

Membership in their own segregated associations does

not help Negroes to success in the larger American society.

*** Negroes are active in associations because they

are not allowed to be active in much of the other organized

life of American society. *** Negroes are largely kept

out, not only of politics proper, but of most purposive and

creative work in trade unions, businessmen’s groups,

pressure groups, large-scale civic improvement and charity

organizations and the like.

2 Myrdal, An American Dilemma 952-53 (Pantheon Paperback 1964).

18

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: RACIAL DEFINITIONS

71. “Ala Code, 1907,.p. 218, Section 2. The term “negro”

within the meaning of this Code, includes “mulatto.” The term

"mulatto” or “person of color” includes persons of mixed blood

descended on the part of the father or mother from Negro

ancestors, to the fifth generation inclusive, though one ancestor

of each generation may have been a white person. (The fifth

generation was substituted for the third generation by the Code

Committee of the 1907 Code. Prior to this, the third generation

was the term used in the laws.) Ala Laws, 1927, p. 716,

redefined mulatto to include a person descended “from negro

ancestors, without reference to or limit of time or number of

generations removed.” The recodification of this section, Ala

Code, tit 1, §2 (1940), includes the following Editor’s Note:

Prior to 1927 a person was a “negro” if descended on

the part of the father or mother from negro ancestors, to

the fifth generation inclusive, although one ancestor may

have been a white person. See Code 1923, §2(5). At this

time there was a great diversity among the states as to the

legal definition of a “negro,” which resulted in the

regrettable situation of a person today being legally a

white person, and tomorrow after a short migration, being

legally a colored person. In 1927, the legislative bodies

of a great many states, working along the same line, amended

their statutes so as to define the term as defined in the

instant section. This definition, while a strict one, has

the advantage of being sure and uniform.

Ala Code, 1975, §1-1-1 eliminated the word “Negro” from its

definitions.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: MISCELLANEOUS RACIAL LAWS

19

72. Ala Const, 1865, Article IV, Section 36. The general

assembly shall enact such laws at its next session, and from time

to time thereafter, as will protect the freedmen of the State,

and guard them and the State against evils that may arise from

their sudden emancipation. There is no equivalent provision in

the 1868 Constitution, and thus this provision was repealed by

implication.

73. Ala Acts, 1915, pb. 727. It is unlawful ‘to require any

white female nurse to nurse in wards or rooms in hospitals,

either public or private, in which Negro men are placed. It is

unlawful for any white female nurse to nurse in wards or rooms in

hospitals, either public or private, in which Negro men are

placed. Penalty, a fine of $10 to $200, and there may also be

added confinement in county jail, or hard labor for county not

exceeding six months. Later codified as Ala Code, 1940, tit. 46,

§§188-9; repealed and replaced by Ala Acts, 1945, p. 98; codified

as Ala Code, 1958, tit. 46 §189(19); repealed by Ala Code, 1975,

$1-1-10.

74. ‘Ala Laws, 1923, p. 152, §29. Tax collector to record

the sex and race of each person paying poll tax. Later codified

as Ala Code, 1923, 83035; modified by Ala law, 1935, p.256;

codified as Ala Code, 1940 & 1958, tit. 51, §244; repealed by Ala

Code, 1975, §1-1-10.

75. Between 1930 and 1957, Alabama executed 2 whites and 18

blacks for rape. Federal Bureau of Prisons, Federal Prisons 99

(1957); Federal Bureau of Prison, National Prisoner Statistics

20

(1956) .

76. In 1961 Gov. John Patterson authorized the disbursement

of $3,000.00 from the Governor’s Emergency Fund to Wesley Critz

George to write The Biology of the Race Problem, which asserted

the biological inferiority of blacks. McMillen, The Citizens’

Council: Organized Resistance to the Second Reconstruction,

1954-64 (1971), p. 169.

77. At least twice, the Governor of Alabama was personally

enjoined from interfering with attempts to desegregate schools.

United States v Wallace, 218 FSupp 290 (ND Ala 1963); United

States v Wallace, 222 FSupp 485 (MD 1963) (Five-judge court).

78. In a joint resolution commending Governor Wallace “for

his prompt action in dispatching the Alabama Highway Patrol and

other law enforcement officers to Birmingham to quell the mob

violence in that city,” the Legislature also stated that ”the

federal government has long assumed a policy of tacit

encouragement and active support of irresponsible racist

agitators sent into this state to defy our laws and to

deliberately inflame unstable emotions into frenzied, savage,

racial violence.” In a commendation to the state public safety

director and the state highway patrol, the Legislature

characterized the disturbance as ”depredations upon persons and

property incited by out of state racist agitators”. Ala Acts

1963, p.388.

ELECTION PRACTICES AND FACTS

21

79. The winner in the Democratic primary for a place on the

County Commission has, in the past, been the winner in the

general election for that place.

80. The Republican and Democratic Parties use a runoff

primary for county commission positions if no candidate has

received a majority in the first primary.

RACIAL APPEALS IN ADVERTISING

81. Subtle or overt racial appeals have been used in

political campaigns in the County within the last 20 years.

82. Carl Elliott, running for US Congress in the 1964

Democratic primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout his

district stating that he had opposed every civil rights bill for

15 years. An example of this ad is found in the Birmingham News,

31 May 1964, p.B5.

83. George C. Hawkins, running for Congress in the 1964

Democratic primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout his

district that stated his support for “states rights,” which were

code words or shorthand for opposition to federal civil rights

legislation. An example of this ad is found in the Birmingham

News, 29 May 1964, p.7.

84. George C. Wallace, running for the 1964 Democratic

nomination for President, ran ads in the newspapers throughout

Alabama on behalf of his delegate slate stating his and their

support for ”states’ rights,” which were code words or shorthand

for opposition to federal civil rights legislation. An example

22

of this ad is found in the Birmingham News, 3 May 1964, p. B4.

85. John Patterson, running for governor in the 1966

Democratic primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout Alabama

claiming that he had defended Alabamians’ constitutional rights

from 1959 to 1963 and called on Alabamians to elect him so the

State could “return to our winning ways” on civil rights issues.

Example of these ads are found in the Birmingham Post-Herald, 29

April 1966, p.8, and 22 April 1965, p.20.

86. Lambert Mims, running for US Senate in the 1972

Democratic primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout Alabama

saying, ”He will return schools to local control.” He advocated

removal of federal court orders desegregating schools. An

example of this ad is found in the Birmingham News, 29 April

1972, +p. 7.

87. Walter Flowers, running for Congress in the 1972

Democratic primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout his

district stating that he believed in “returning] control of

schools to local and state authorities.” He advocated removal of

federal court orders desegregating schools. An example of this

ad is found in the Birmingham News, 27 April 1968, p.6.

88. George C. Wallace, running for Governor in the 1970

Democratic primary runoff, ran ads in the newspapers throughout

Alabama claiming that “militant blacks” had ”bloc voted” against

him and for Albert Brewer. Brewer received the endorsement of

all the black and predominantly black groups who made

endorsements.

23

89. The Alabama Republican Party ran ads in the newspapers

throughout Alabama in 1976 for “President Ford and his Alabama

team” stating that Jimmy Carter was in favor of “busing,” meaning

forced busing to achieve school desegregation. An example of

this ad is found in the Birmingham News, 24 Oct 1976, p.2B.

90. Albert Lee Smith, running for Congress in the 1978

Republican primary, ran ads in the Birmingham newspapers accusing

the incumbent John Buchanan of supporting “forced busing of

school children” to achieve school desegregation. An example of

this ad is found in the Birmingham News, 4 Sept. 1978, p.48.

Buchanan received the endorsement of all the black and

predominantly black groups who made endorsements.

91. Dan Wiley, running for US Senate in the 1978 Democratic

primary, ran ads in the newspapers throughout Alabama accusing

his opponents Maryon Allen and Donald Stewart of promising the

Alabama Democratic Conference that they would work for electoral

systems which guarantee more black elected officials. An example

of this ad is found in the Birmingham News, 24 Aug. 1978, p.55.

Stewart had received the endorsement of all the black and

predominantly black groups who made endorsements.

92. George Williams, running for Alabama Supreme Court in

the 1982 Democratic primary, ran ads asking voters to "look

closely” at the candidates for the State Supreme Court, Place 3,

and including pictures of himself, Justice Oscar Adams, and Jim

Zeigler. An example of this ad is found in the Birmingham News,

1 Sept. 1982, p.138A.

24

Se pA *

93. It is unusual for one candidate to run an ad with his

opponent’s picture in it.

STATE POLICY ON SINGLE-MEMBER DISTRICTS

94. The use of at-large elections for county governments is

a tenuous state policy.

95. Most counties in Alabama have used single-member

districts for the nomination or election of county commissioners

at some time.

96. The general law of Alabama has provided for the

election of members of county commissions at-large since 1852.

There have been and are still exceptions to this general rule.

97. Each of the following counties now elects (or will

elect at the next election) its county commission using

single-member districts:

Autauga

Barbour

Blount

Butler

Chambers

Choctaw

Clarke

Colbert

Conecuh

Coosa

Dale

Escambia (adopted single-member districts in a referendum, but

| has not yet implemented the law)

Geneva

Greene

Hale

Lamar

Lauderdale

Limestone

Lowndes

Marion

Mobile

25

Monroe

Montgomery

Perry

Pike

Raldolph

Russell

Sumter

Tallapoosa

Tuscaloosa

Washington

Wilcox

ELECTION PRACTICES AND FACTS

98. Election practices such as at-large elections, runoffs,

and numbered places discriminate against blacks, according to

empirical studies published by reputable political scientists.

99. Most black candidates are at a disadvantage in waging

successful at-large campaigns in the County due to lack of

financial resources and lack of access to campaign organizational

skills outside of the black community.

100. Blacks have almost no chance of being elected at large

to the County Commission.

101. Successful campaigns in the County are waged with the

assumption that voters vote along racial lines. Thus candidates

target a winning coalition assuming they will get the black vote

or alternatively they try to minimize the black:white ratio (by

minimizing the black vote or by maximizing the white vote).

26

Submitted by,

0 2/

Edward Still

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham AL 35233-2810

205/322-6631

Vv

James U. Blacksher Terry G. Davis, Esq.

Larry Menefee, Esq. Seay & Davis

Wanda Cochran, Esq. P.O. Box 6125

Blacksher Menefee & Stein P.A. Montgomery, AL 36106

P.O. BOX. 1051

Mobile, AL 36633

Julius L. Chambers, Esq. Reo Kirkland, Jr., Esq.

Deborah Fins, Esq. P.O. Box 646

NAACP Legal Defense Fund Brewton, AL 36427

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, the undersigned attorney, do hereby certify that, prior

to or immediately after filing the foregoing with the Court, I

mailed or delivered a copy to:

Alton L. Turner, Esqg., Turner & Jones, P.A., P.O. Box 207,

Luverne, AL 36049

D.L. Martin, Esqg., 215 South Main Street, Moulton, AL 35650

David R. Boyd, Esq., Balch & Bingham, P.O. Box 78,

Montgomery, AL 36101

Jack Floyd, Esqg., Floyd Kenner & Cusimano, 816 Chestnut

Street, Gadsden, AL 35999-2701

¥.0. Kirk, Jr., Esg., P.O. Box A~-B, Carrollton, AL 35447

H. R. Burnham, Esq., Herbert D. Jones, Esq., P.O. Box 1618,

Anniston, AL 36202

Warren Rowe, Esg., P O Box 150, Enterprise AL 36331

Barry D. Vaughan, Esg., 121 North Norton Avenue, Sylacauga,

27

Ny

AL 35130

James Webb, Esqg., P O Box 238, Montgomery AL 36101

ee M. Otts, Esg., P O Box 467, Brewton AL 427

2 /

28