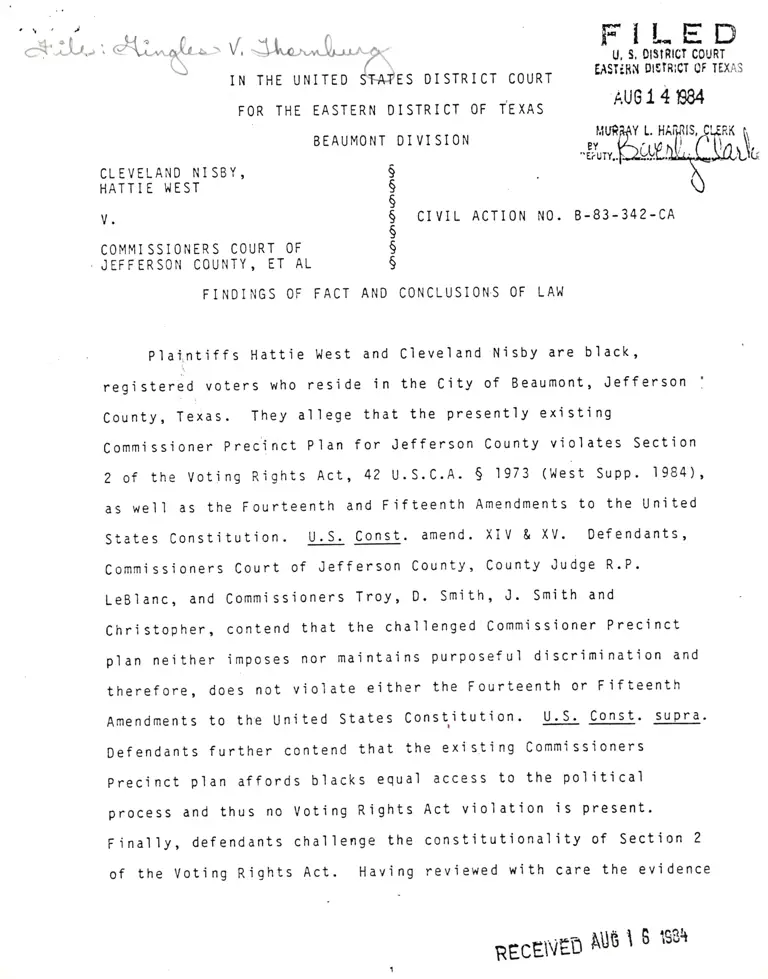

Nisby v. Commissioners Court of Jefferson County Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Public Court Documents

August 14, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Schnapper. Nisby v. Commissioners Court of Jefferson County Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, 1984. bd2998b2-e292-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a0de6cd8-4c4d-45da-a09c-e4f051d08409/nisby-v-commissioners-court-of-jefferson-county-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

FI

U, S,

EASIi'iN

D

RT

TEXA

6l' i L,,, r ,{i.^,^ qG " - /, --f,lno n Jtru, 7'\)

IN THE uNITED irs?rs DISTRIcT couRT

FOR THE EASTERN

BEAUMONT

CLEVELAND NISBY,

HATTiE l,JEST

V.

otstRtcI cou

Dts?B|CT 0r

DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DIVISiON

AUG 1 4W

YL.LluR

EY,.E7UTY.

S,

CI VIL ACTION NO. B-83.342.CA

COMMI SSIONERS COURT OF

J EF F ER SON COU NTY , ET AL

FI NDI NGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAl^/

p'l ai,nt'iffs Hattie west and cleveland N'i sby are b1ack,

regi stered voters who resi de i n the Ci ty of Beaumont, JBfferson :

county, Texas. They al1ege that the present'ly existing

Commjss'i oner Prec'inct Plan for Jefferson County violates Section

2 of the Voting R'i ghts Act, 42 U.S.C.A. $ .l973 (West Supp. 'l 984),

as wel I as the F ourteenth and F if teenth Amendments to the U n'i ted

States Const'i tutjon. U.S. Const. amend. XiV & XV. Defendants,

CommissionerS Court of Jefferson County, COunty Judge R.P.

LeBlanc, and commissioners Troy, D. Smith, J. smith and

Christopher, contend that the challenged Commissioner Precjnct

plan ne.i ther imposes nor maintains purposeful discrim'i nat'i on and

therefore, does not violate either the Fourteenth or F ifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. U.S. Const. supra-

Def endants f urther contend that the ex'i sti ng Comm'i ssionerS

precinct plan affords blacks equal access to the pol'itical

process and thus no Voting Rights Act v'i olatjon is present.

F.i nally, defendants chal'lenge the constitutionality of Sect'i on 2

of the Vot'i ng Rights Act. Having rev'i ewed with care the ev'i dence

5

s

s

s

s

5

s

,L\U

RECEIVEDAUB\6$3!r

and post-tri al bri efs submi tted by the parti es, the Court i n

accordance with Ru'le 52, Fed. 8. Civ. P., hereby enters its

Findings of Fact and Conclus'ions of Law.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Background

'l . ) Jef f erson County, Texas possesses a heterogeneous

populat'ion, 28.2/. of the population is b1ack, 4.1% is hispanic.

Approximately 96i^ of the black populat'ion is concentrated in the

county's two urban centers, Beaumont and Port Arthur.

2.) The principa'l iounty governance entity is the Commissioners

Court of Jef f erson County (Comm'i ssi oners Court) . .The I aws and

Constitution of Texas conf er upon the Comm'i ssioners Court

numerous admin'istrative and legislative powers and duties,

including:

a. ) prepari ng and adm'i ni strati ng the budget f or county

expend jtures, Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. art. 689a-'l , et. seq.;

b.) aud'i t'i ng, SBttl'i ng and directing payment of al'l

accounts agai nst the county, Tex. Rev. Ci v. Stat. Ann. art. 235 I ;

c. ) establ i shi ng, B&i ntai ni ng and control'l i ng publ i c

ferries, bridges and highways, ISj. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. art.

2351, ?356 & 2357;

d.) construction and repair of all necessary pubf ic

buildings, Tex. Rev. C'i v. Stat. Ann. art. 2351 & 2372i;

e. ) establ i shi ng county hospitals, Tex. Rev. Ci v. Stat.

2

Ann. art.f 4478;

f.) providi

'i diots, Tex. Rev.

2d Counties S 35.

3.)PursuanttoArtjc]ev,sect.ionl8(b)ofth.eTexas

constitution, the commissioners court has div'ided the county into

four preci ncts each of whi ch el ects one county commi ssi oner ' The

f jfth member of the comm'i ssioners court, the county Judge' is

el ected at- 1 arge -

4.) The present demographic composition of the four

commi ssi oners preci ncts i s as fol I ows:

preq.i nct Total Popu'l ation Black Population x Black

ng for

Civ.

the

Stat.

support

Stat.

of paupers, lunatics and

Ann. art. 235 I , Cf . Tex. Jur.

22,031 36.6I 60,218

2 63,082 734 1'?

3 '61,661 24,912 4o:4

4 65,971 23'133 35'1

TOTAL 250,938 70,810 25'2

precinct three encompasses the urban black popu'l at'ion of Port

Arthur. Preci ncts one and f our, the f ocal poi nt of the 'i nstant

case, dFe cont.i guous and divide, almost equally, the concentrated

bl ack popu 1 ati on resi di ng i n the ci ty of Beaumont ' The boundary

line between precincts one and four, origina'l1y drawn in 1884'

has been changed severar t.imes, four times since .,949--'i n'l 953'

1965, .l976 & 198.|.

The I 976 reapportionment establ i shed the present boundary

'l ine between precincts one and four. In 'l 981, the comm'i ssioners

Court reapport'i oned the preci ncts. Notwi thstandi ng a proposal to

alter the boundary between precincts one and four, submitted

3

prior to open hearing on 0ctober 5, 198.|, the commissioners court

I eft unchanged the boundary between preci ncts one and four '

5.) The United States Department of Just'i ce prec'leared both the

.|976 and i98'l reapportionments, pursuant to Sect'ion 5 of the

Vot'i ng Rights Act. 42 U.S.C. S 1973c'

6.) In accordance with 28 U.S.C. S 2403(a)(1982), the Court

notif .i ed the uni ted states Attorney General of def endants'

ch al 1 enge to the const i tut i onal i ty of the voti ng R i ghts Act.

H i story of 0f f i c'i al D'i scri mi nati on--Present Ef f ects of P ast

Discrimination.

7 .) The h i story of de iu re and de facto raci a1 segregati on i n

See Graves v.Jef f erson County, Te.xas i s wel I documented'

Barnes, 378 F.2d 640, 648-650 ('I'D' Tex' 1974 ): see qenerallY

Issac, Mun '

409 'Sou thwestern

Historical Quarterly (1975). 0f pervasive scope raci al

.A. (Port Arthur

ISD) 67g F.2d ll04 (5th Cir. .l982);

Un'i ted States v' T'E'A'

Plaintiffs' Ex. 25, and employment' E, €'9',Watkins v'

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe R.F., No. B-78-342'CA, Jun' 6, 1983

(Consent Decree)(8.0. Tex.). That this discrim'i nation impeded

bl ack parti ci pati on i n the pol i t'i cal process 'i s al so wel'l

documented. In Graves, _W, a three-iudge d'i strict court

observed that ,,in the Jefferson County mult'i-member d'istrict

v'i rtual ly every element contri buti ng to the di I ution of the

mi nori ty voi ce 'i s present. " f!. at 648. Thus, rot surpri si ng '

defend ants concede th at b I ack res i dents of Jefferson County have

segregation reached schools, Un'i ted States v' T'

t

E

4

been the victims of past discrimination. Defendants' Post-Trial

Brief at 26.

Notw'i thstandi ng thi s conceSs j on, def endants di spute

a1'legations that past "discrimination ori ginate.d from county

government. 0f courSe, the level of government at which qe iure

segregation orig'i nates is of litt'le import. The critical inquiry

is whether blacks have been denied equal access to participation

i n the pol iti cal process at the county leve'l . Hi stori caI

officjal segregation wh'i ch generates such a result is pert'i nent

whatever its'l evel of init'i at'ion.

7 .) A hi story of offi ci al segregati on does not i pso facto gi ve

ri se to a Voti ng Ri ghts Act vi ol at'ion, otherwi se such a hi story

would provide a perpetual basis for a find'i ng of illegality.

Accordi ngly, a h'i stori cal perspecti ve i s tal uable on'ly to the

extent i t sheds f ight on exi sti ng pract'i ces. l,ihen race neutral

pol i ci es are adopted and i mp1 emented, the paSsage of time may

permit "an inference that what waS true in the past is no longer

true." Kirksey v. Bd. of Supervisors, 554 F -2d .l39, .l44 (5th

Cir.)(en banc), cert. denied,434 U.S. 968 (.l977). Plaintiffs'

Exhs. 13 & 25. In the instant case, though to a signif icantly

reduced degree, what was true in the past is still true.

Djrect barriers to black registration and voting, €.9., poll

taxes, have been evjscerated. Nevertheless, Iumerous indicia

underscore the I i ngeri ng effects of past d'i scrimi nation. Housi ng

patterns remain djstinctly segregated. Pla'intiffs' Exhjbits 12 &

25. Current census data reveals the disparity between the

economic and educational status of the Jefferson County black and

white populat'ions. The median income for white families is

nearly doub'l e that of b l ack f ami l i es. Twenty- ni ne percent of the

black populat'ion, dS compared to 6.1% of the wh'i te population, is

below the poverty level. Moreover, o0 average.the educat'i onal

leve'l of blacks is lower than that of their white counterparts.

Unl i ke some jurj sdi cti ons i n whi ch the resi du al effects of

past di scrim'i nat'i on combi ned wi th past el ect'i on practi ces

diminished black voter registration and turnout, Maior v. Treen,

574 F.Supp. 325, 34.| (l',l.0. LA. l9B3) (three iudge district

court); see Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 6.l3, 624-26 (.l982), in

recent e'l ections, in the preci ncts pert'i nent to thi s case, black

and white voter registration and turnout have reached a state of

parity. (Tr. 25-27,164-67, defendants Exhs. ll &.35). Still, a

sophi st'i cated exami nati on of exi st'i ng condi t'i ons reveal s that

present effects of past di scrimi nation impede equal access to the

political process.

Polarization

9.) To a prodigious degree, e'l ections in Jefferson County

are characterized by racial bloc voting. (witnesses for both

plaintiffs and defendants held th'i s view. Tr. .l4, ?9, .l83-84).

Moreover, the Court i s conv'i nced that race of ten i s an outcome

determ'inative factor in Jefferson County elections, and that a

substant'i al percentage of the white e'l ectorate consider the race

of a b'l ack candidate as a negati ve f actor in their evaluation of

black candidatgs. Plaintiffs Exhs. 32 at 22-?3 (depos'i tion of

County Judge LeB I anc ) .

.10.) Plaintiffs'corre'l ation or regression analys'i s, P'l aintiffs'

exh.'l 5-16, underscores the significant degree of racial

po'l arization. The Court recognizes that standing a'lone such

correlat'i on scores may be nondeterm'i native and."that there wil'l

almost a'lways be a raw correlation with raCe in any fai'l ing

candi dacy of a m'i nority whose raci al or ethn'i c group i s . I a

smal l percentage of the total vot'i ng populationl." Jones v. City

of Lubbock,730 F.2d 233,

?.rO

(5th Cir. .l984)(Higginbotham,

J.,Specia'l concurrence) (In City of Lubbock, the population waS

. 8.2% black and 17.9% Mexican-American). But the presence of

substanti al corroborati ve evi dence leads the Court to conc'l ude

that the polarization scores submitted by P'l aintiffs'i n fact

reveal what they purport to reveal.

1.|. ) Exacti ng scruti ny of Jefferson County election results

unmasks a nearly unif orm pattern: B'l ack candi dates f are poor'ly

in predominately white precincts whether they win or lose the

election. The Apri I I 982 l.lard 3 Beaumont City Counci I electjon

is illustrative. 0n April 3, in a four way race, three black

cand j dates garnered 'less than 50U of the wh'i te vote. Candi date

Ivey, a white, cdptured 52.4% of the white vote. 0n Apli I .|7,

.1982 , 'i 0 a run-of f el ecti on between cand'i date Deshotel , a bl ack ,

and Ivey, Ivey secured 79.3% of the wh'i te vote, Deshotel 20.7%.

Deshotel won 98.5% of the b I ack vote, I vey I .5%. A'lthough

Deshotel prevai 1ed, securi ng 51 .7% of the tota'l vote, the I osi ng

candidate, a white, finished far ahead in predominately whjte

precincts. Moreover, with but one exception, see Defendants'

Exh. (8 State Representat i ve, d'i stri ct 7 A--May, .l976

) , a bl ack

cand i date has not captured a maj ori ty of the wh i te vote.

Defendants' Post-Trial Brief at 39-4'l . At bottom, this fact is

not attri butable to an expected correlation between losi ng and

low vote totals, but instead ref lects a direct.'l 'i nk between

candj date race and performance i n raci a1 1y i dentifi able

di stri cts.

12.) The Court is unpersuaded by defendants proffered

alternat'ive explanations for the high correlation between a

cand j daters race and hi s/her degree of success i n predomi nate'ly

wh'i te prec'i ncts. Specjfical'ly, the Court conc'l udes that campaign

style and scope have had minor impact on the performance of black

candidates in predominately white precincts. In the .l982 City

Counci I race descri bed above, cand i date Deshotel executed a

campa'i gn whi ch def endants descri be as " an exampl e

'of

ef f ect'i ve

campaigning reaching beyond the black community," Defendants'

P ost Tri al Bri ef at 43, i . e. , a campai gn of appropri ate styl e and

scope. i t wou I d seem di s'i ngenuous to suggest that campai gn sty'le

and scope, Iot race, are significant factors when a "proper'ly

implemented" community-wide med'i a campaign garners a mere ?0% of

the white vote. Defendants' Exh. 8 (1982 City Council Race, Ward

3.)

13. ) The Court f i nds simj I ar'ly unpersuasi ve def endants' argument

that 'i ncumbency has pl ayed a more cri ti cal ro'le than race i n past

Commi ssioners Court races. Defendants' Post-Trial Brief at 46.

Since 197?, blacks have run for County Commissioner four t'imes.

In the 1972 race in precinct one, both a black candidate and a

white candidate challenged a white incumbent in the Democratic

8

prjmary. The white chal lenger po1 1ed 5lf of the white vote, the

white s'i ncumbent 43.7% and the black challenger 5.31.

Curi ous1y, i n the run-off el ecti on, i ncumbency once agai n fai l ed

to prevent the white challenger from garnering.more whjte votes

th an the wh i te i ncumbent.

In the \974 precinct four race, three whites and a black

challenged a wh'i te jncumbent. In the Democratic primary, the

black received 3.81 of the white vote less than any other

cand'i date. The three white cha'l lengers combined to secure 66.4%

of the white vote. By comparison, the white incumbent won 29.8/,

of the white vote. As happened in like prec'i nct one in 1972, the

wh'ite chal lenger outpolled the white incumbent in white preci ncts

'i n the run-off election by a marg'i n of 56.3% to 43.7%-

I n the 1 97a preci nct one el ecti on, 0o j ncumbent ran for

reelection. 0f f ive candidates'i n the democrat'i c primary, the

one black candidate rece'i ved 4.3% of the white vote, the four

whjte candidates rece'i ved the remaining 97.7%. In the runoff ,

the white candidate rece'i vewd 88.3% of the white vote, the black

cand'i date won the remai ni ng 11 .7%. Last'ly, i n the 'l 982 preci nct

one election, the white incumbent received 80.6U of the white

vote, the black challenger, 19-4%.

Both " common SenSe and i ntu i ti ve aSSeSSment. .. powerful

components to th'i s critical factua'l inquiry...." City of

Lubbock, 730 F ,?d at 234 (Hi gg'i nbotham, J. spec'i al concurrence)

lead to the i nexorable concl usion that race remai ns a si gn'if i cant

f actor i n whi te voters dec'i si on maki ng.

Extent Elected

'14.) No black candidate has been elected County Commissioner jn

Jefferson County, Texas. Defendant's assertions notwithstanding,

this fact is primari1y attributable to racial factors. In

Jeff erson County, almost without except'i on the.fol'l ow'i ng is true:

both the black and wh'i te electorates we'i gh heavily the race of a

cand'idate--blacks preferring blacks, whites preferring whites.

Because wh i te voters are a si gni f icant ma j ori ty 'i n both preci ncts

one and four, whi te candi dates have won.

Slatinq - Racial Appeals

.|5. ) Pl a'i ntif f s adduced no persuasi ve evi dence that

raci a1 1y-b i ased s1 ati ng has occurred i n recent Jefferson County

elections. Though one of p1 ai ntiffs' witnesses testified to the

existence of candidate slat'i ng groups (Tr. 28-29), there was no

ind'i cation that blacks have been excluded in recerit elect'ions.

.l6.) plaintjffs offered no evidence that overt racial appeals

have occurred since 1972.

Responsiveness - Swing Vote

I 7. ) County Commi ssi oners i n Jefferson County have been

responsi ve to the concerns and needs of thei r bl ack constituents.

The Court 'i s i ntimately f am'i I i ar w'i th the al I too common

i nci dence of de iure segregati on i n the d j stri but'i on of

governmental largess, services and employment. The record of the

Commjssioners Court over the past decade stands in stark contrast

to the genera'l pattern of obdurate conduct exhi bited by state

officials respons'i ble for ensuring the eradication of de iure

segregat i on. To the extent that empl oyment and appo'i ntment of

bl acks cont'i nued or even accelerated duri ng the pendency of the

1n

i nstant 1 i ti gati on, the Court fi nds that such hi ri ngs and

appoi ntments are the product of genu i ne efforts by the

Commissioners Court to eradicate residual effects of past

discrimination, and were not in any way causa'l 1y linked to this

su i t.

I 8. ) The Court found the testimony of Commi ssi oner Chri stopher

and County Judge LeBl anc forthri ght and di rect and was persuaded

that both are responsi ve to their black constituencies.

19.) The Court found persuasive the following evidence bf

responsi veness:

a. ) an express effort by Judge LeBlanc to become fami I i ar

w'i th black ind'i v'i duals who are interested in particular areas and

who possess skills and abil'i ties wh'i ch w'i ll enhance the quality

of pub'l i c serv i ce. (Tr. at 'l l3 ) ;

b. ) the actu al record of appoi ntments of bl acks and

hispanjcs to major boards and commissions, including: three

bl ack members, out of twel ve, on the Jef f erSon County Chi'l d

g1elf are Board; one black and one hispanic member, out of S'i x, on

the Southeast Texas Regional Mental Health/Mental Retardat'ion

Board; two b I ack members , out of si x, on the Mental Heal th/Mental

Retardat'i on Publ ic Responsibi l ity Comm'i ttee; approx'i mateiy

one-fourth of the Jefferson County appoi ntees to commi ttees of

the Southwest Texas Regional Plann'i ng Comm'i ssion are minorit'ies,

of these approx'imately B0% are bl ack. See def endants' Exhs.

3l-32 for add jt'i onal examples. (Tr. at ll0-.l3);

c.) appo'i ntment of a black as a Judge for a County Court

at Law posit'ioni (Tr. at .l08);

11

d.)imp.|ementationofanaffirmativeact.ionplantofoster

increased hiring of blacks for county iobs. (Tr. at .l01-02 & .l59)

'

Moveover,theCountyComm.issionershaverequestedCounty

officials not directly under the'i r control to i'ncrease minority

hi ri ng. (Le Bl anc DeP ' at 11-'l 2) ;

e.)roadServicesareequitab.lyproVidedtoblackand

wh'i te consti tuents. (Tr. at 129 ) ;

f.)theCommiss.ionerScourthasact.ivelyrespondedto

b1 ack consti tuents' concerns regardi ng hea'l th care for i ndi gents '

grievance procedures for county employees' ia'i1 conditions, food

stamps and surp'l us commodit'i es. (Plaintiffs'Exh' 31 defendants

comm.i ssioners courts' Answers tO Pla'i ntiffs' second Set of

InterrogatoriesNos.l&2,defendantLeBlanc,Jr.'sat9&ll0).

20.)Defendantscontendthattheblackelectoratemayexercisea

,,swingvote,..inthoseelectjonsinwhichthewhiteelectorate

fragmentsitsvotepreventinganyonecandidatefromwinningthe

elections.Defendantsconcludethatthebjackelectoratethus

poSSeSSeS Some degree of pol.i tica1, bal.|ot.box c]out. Def endants

direct the court's attention to the 1972 and 1974 CommissionerS

court el ecti ons i n whi ch the bj ack el ectorate p1 ayed a deci si ve

ro'l e. 5ee, def endants' Exh' 8'

Thoughtheoreticallysound,thepol.itica.lpoweraSsertedly

derived from being a,.swing vote,.e]ectorate has proved to be

illusory in Jefferson county commissioners court e'lections' That

def endants f ai 1 to poi nt to any 'i nstance of the sw'i ng vote

phenomenonduringthepastdecadeistelling.Perhapsof

paramountsignif.icanCeisthetestimonyofCommissionerTroyand

12

County Judge LeBlanc that a candidate who advocated policies

favored by the black electorate, f3!, d candidate who appea'led

for black votes by supporting positions popular among black

voters, would have diff iculty being elected. (Tr. at .l18 &'l 56).

It is incongrous to label as a "swing vote" a portion of the

electorate to whom candidates cannot d'i rect political appea'l s

w'i thout fear of alienating the white majority. In other words,

the role as a "swing vote" constituency is of little value if

candi dates who appeal to the " swi ng vote" suffer the effects of a

"wh'i te backlash" and proceed to lose

Tenuousness

21. ) The evj dence pert i nent to tenousness does not preponderate

one way or the other. The purported cri teri a for choosi ng among

the several p1 ans before the Commi ssioners Court in I 98.l , e. g.

county road mi leage and one-person-one-vote requirements, possess

a nexus to the function of the Comm'i ss'i oners Court, and

therefore, dt least i n the abstract, dFe nontenuous. Moreover,

the' road mi'l eage vari ances between preci ncts are i nsuf f i ci ent to

permi t an i nference of impermi ssi ble motj vati on i n adopti ng the

present precinct lines.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

l.) Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.A.

S 1973, is constitutional. Jones v. C'i ty of Lubbock, 727 t.2d

364, 372-75 (5th Cir. 1984).

2.) Preclearance of the I 976 & l98l preci nct reapportionments by

the Un'i ted States Attorney General, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. $1973c,

is of no probative value to the Section 2 issue before the Court.

a

i3

Major v. Treen,574 F.Supp 325,327 n.l (bl.D. La. 1983)(three

judge d'i stri ct court) ; Report on S.1992 of the Senate Comm'i ttee

on the Judi c'i ary, S. Rep. No . 97 -417, 97th Cong. , 2d Sess. 1982 at

177.

Standard of Review - Sect'i on 2

3.) Section 2 "requires the court's overall iudgment, based on

the total'i ty of the c'i rcumstances and gu'i ded by those rel evant

factors jn a particular case, of whether the voting Strength of

m'i nority voters is, in the language of Fortson v. 0orsey,379

u. s. 433 ('l 965 ) , and Burns v. R i chardson, 384 u. S. 73 ( .l966

)

'min'imized on cancelled out.'u !. f ep. No. 97-417 at 29 n. ll8,

repri nted 'i n, .l982 U.S.- Code. Cong. & Ad. News at 207 n. 1.|8

( emphasi s added) . I n eval u ati ng the rel ati ve wei ght to be

accorded to each parti cu I ar factor, congress determi ned that

courts should eschew a mechanist'i c methodology. Instead,

Congress ,,d'irected the courts to apply the obiective factor test

flexjbly. . .,. Jones v. C.i ty of Lubbock,727 F.2d at 384.85.

The Total i ty of The Ci rcumstances

4. ) The facts adduced at tri al suggest that two of the numerous

f actors consi dered are centra'l to the Court's determi nat'i on of

whether bl acks enjoy equ al access to the poI i ti cal process at the

Commissioners Court level in Jefferson County, T€xas' they are:

po'l ari zation and respons'i veness.

In Rogers v. Lodge,458 U.S.6l3 (1982), the Supreme Court

explained the odious nature of polarization: "Voting along

rac.i al I i nes a'l I ows those el ected to i gnore b'l ack i nterests

without fear of political consequences, and without bloc voting

1d

the mi nor i ty cand i dates

of their race., Id. at

38.| ("polarized vot'i ng

remains at issue'i n the

would not 'l ose elections solely because

6?3; accord City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d at

conf i rms that race, dt I east subt'ly,

political system" Id.).. Bloc voting,

however, "does not unconstitutionally di'lute voting strength

without reference to the other Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297

(5th Cir. 1974)(en banc), factors." Id. at 385 & n..l7. That

po1 arization and respons'i veness are interrel ated i s obvious from

Lodge and City of Lubbock. The purpose of ensuring equal access

to the politica'l process'i s to ensure that elected officials are

respons'i ve to the entire electorate. In other words, polarjzed

voti ng by whi tes may ef f ecti ve'ly di senf ranchi se a bl ack mi nority

or vice versa.

It would seem that evidence of sign'if icant responsi veness

should undercut any negative inference which could be drawn from

the exj stence of racj al bloc voti ng. The relevant i nquiry would

seem to be: to what extent i s the governmental entity responsi ve

(a quantitative determ'i nation). But the inquiry is not so simple

In City of Lubbock, supra, the Fif th Circuit, per Judge Randal'l ,

impl i ed that the respons'i veness i nqu'iry i s composed of a both a

qua'l itati ve component and a quantitati ve component. Judge

Randal l observed that "Iw]hether or not City offici al s do iqnore

minority interests, p0lorization nevertheless frees them of

politjcal reprisa1 for disadvantaging the minority community."

City of Lubbock,727 F.2d at 38,| (emphasis added). Thus, the

benevolent form of responsiveness present i n the i nstant case,

laudible though jt may be, js insuffic'i ent in a qua'l itat'i ve sense

to eviscerate the exclusionary implications of po'larization. in

a practical sense, potent'i al voter ballot box coercion must

underlie responsiveness; good conscience and an enlightened

soc'i a1 vi ewpo j nt are theref ore not enough. Accordi ngly, because

the responsi veness demonstrated here by the present

Commissioners could evaporate without negative pol'itical

consequences, b1 acks do not enjoy equal access to the pol i ti cal

pr0cess.

5.) In Kirksey, j!jj3, the Fifth Circuit noted that "the absence

of black e'l ected off icials in a county where approximate'ly 35% of

the voting population is black is an indicat'ion that access of

bl acks to the pol i ti cal process i s not yet unimpeded. " Ki rksey,

554 t.2d at .l46. The compos'i t'ion of both precincts one and four

i s approx'i mately 35% bl ack. The Court 'i s convi nced that the

jnference drawn in Kirksey is app'l icable in the 'i nstant case.

See, supra, Finding of Fact No. .I4.

6.) Based on the totality of the circumstances the Court is of

the opinion that the pof itical process for election to the

Jefferson County Commi ssi oners Court i s not equ a1 1y open to

part'i cipation by blacks, and accordingly, plaintiffs are entitled

to judgment on their Vot'i ng Rights Act claim. The instant case

is paradigmatic in one respect: It represents a growing group of

cases in which courts must endeavor to identify the border which

separates an assurance of equal access on the one hand from an

i mposi ti on of a proport i onal representati on scheme on the other,

the f ormer statutori 'ly and consti tut'iona11y prohi bited. See

Wh'i te v. Regi ster , 41? U. S. 755, 765-70 ( .l973) ; l,lhitcomb v.

Chav'i s, 403 U.S. 124, 156-57 (197.|);

(l,Jest Supp. 1984) . That the 'l i ne of

two theoretical concepts 'i s imprecise

intricate iudicia'l inquiry when rea'l

task.

42 U.S.C.A.

demarcat t'on

gi ves ri se

worl d appl i

Section .l973

between these

to a difficult'

cation is the

Compound'i ng the comp'lexity of this'i nquiry is the anamolous

role racia'l bloc voting plays in the Section 2 calculus. l'lhen

wh j tes consti tute a ma jori ty, whi te bloc vot'i ng bars equal

acceSs, i.e., blacks lose because they are black regardless of

the'i r qu al i cat i on s . 0f course, ds noted above ,

of Law No. 4 suFFd, rac'i al bloc voting does not

rise to a statutory. violation, rather a confluence of factors

must be preSent. Black racial bloc vot'i n9, however, lies at the

core of concerns that a remedial plan'imposes propOrtional

representati on. I n other wordS, bl ack raci al voti ng 'i S a

prerequisite to assertat'i ons that a majori ty black district

creates a safe haven. Blacks thus confront a quandry, if they

vote al ong raci al l'i nes i n an attempt to gai n equal acceSS but

fail to do So a remedy may be unavailable because the'i r bloc

voting may perm'i t the proport'i onal representat'ion'l abel to be

appl i ed to any court imposed remedi al measure. Thus, i n theory,

the pol ari zati on phenomenon wh'i ch frdY, i n part, dCcount f or a

Section ? violatjon may simultaneously preclude a court ordered

remedy. Here, the Court must descend from the theoretj cal

p'l ane and address the pragmat'i c implicat'i ons of polari zation. As

stated above, the Court concludes that blacks do not enjoy equal

acceSS to the pol itical process for electing members of the

see

ln

Concl usi on

itself give

t7

Commisssioners Court. The Court further conc'l udes that requiring

reapportjonment in th'i s case does not enter the rea'lm of imposing

propor t i on a I repre sen t at i on.

7 .) G'i ven the court' s concl usi ons rel ati ng to .the exi sti ng

Commi ssj oners Court preci nct p1 an for Jefferson County, the Court

need not reach pla'i ntiffs claims of constitut'i onal violations.

Remedy

8. ) Af ter a court determi nes that an ex'i sti ng apportionment

scheme i s unl awf ul, the legi sl ati ve ent'ity responsi ble f or

drafting a districting plan is entit'l ed, whenever feas'i b'le, to

formulate a new p1an. Wise v. Lipscomb,437 U.S.535,540 (.l978)

Because the next Commjss'i oners Court electjon is not imminent,

the Court invjtes the Commissioners Court to present to the Court

a new plan on or before 0ctober 15,.l984. If the parties cannot

prepare i n the time g'i ven a proposed p1an, they may petition the

Court for an extensjon.

The interrelationsh'i p between findings of responsiveness on

the one hand and severe racial bloc voting on the other is an

area ri pe f or the appel I ate court to provi de addi t'i onal

gu i del i nes to the tri al courts. I n the event of an appeal i n

thi s case, hopef u'l 'ly, thi s question can be addressed by the F if th

Circuit to the effect of establishing a c'i rcuit rule.

It is so 0RDERED.

AugustSIGNED ANd ENTERED thiS

UNITED STATES DISTRiCT JUDGE