Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Slip Opinion

Public Court Documents

July 2, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman Slip Opinion, 1979. 4dd33e77-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a1fd586f-0ea3-40cb-aa9b-e00aa3cabb7d/dayton-board-of-education-v-brinkman-slip-opinion. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

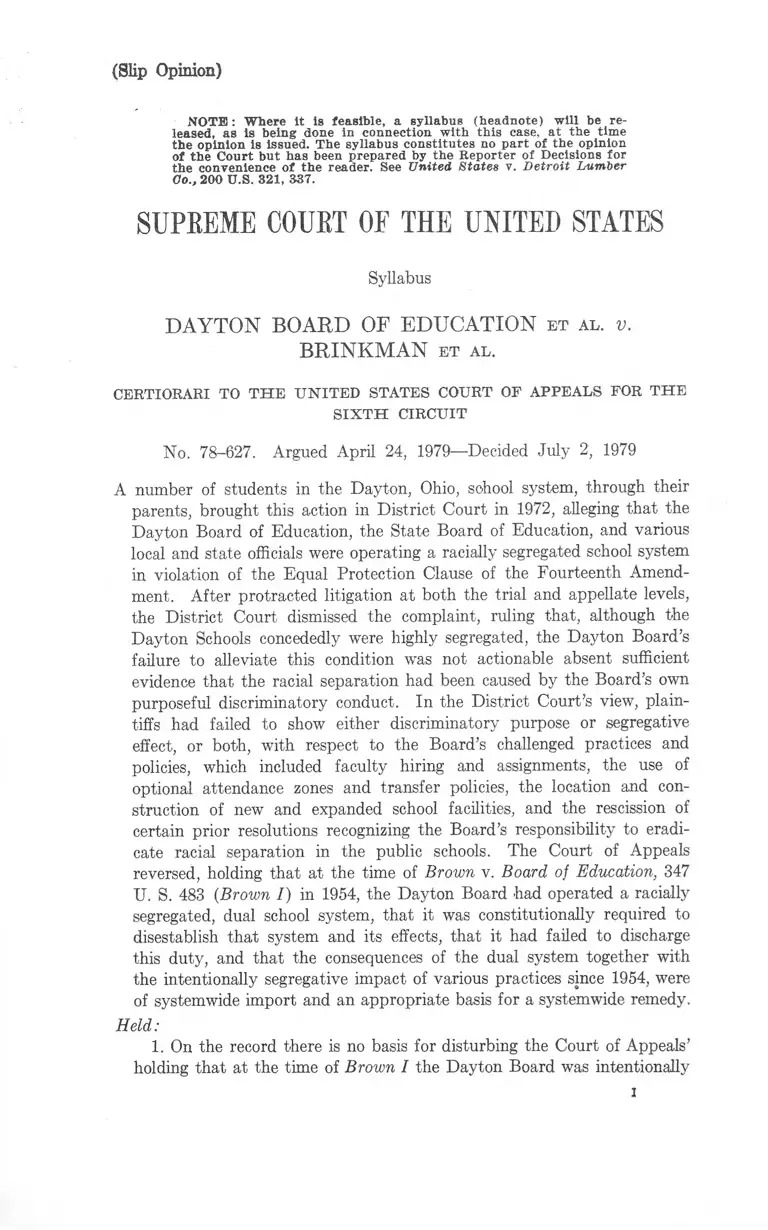

(Slip Opinion)

NOTE: Where It is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be re

leased, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time

the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion

of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for

the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Lumber

Cfo., 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPEEME COUKT OE THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION e t a l . v .

BRINKMAN e t a l .

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 78-627. Argued April 24, 1979— Decided July 2, 1979

A number of students in the Dayton, Ohio, school system, through their

parents, brought this action in District Court in 1972, alleging that the

Dayton Board of Education, the State Board of Education, and various

local and state officials were operating a racially segregated school system

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. After protracted litigation at both the trial and appellate levels,

the District Court dismissed the complaint, ruling that, although the

Dayton Schools concededly were highly segregated, the Dayton Board’s

failure to alleviate this condition was not actionable absent sufficient

evidence that the racial separation had been caused by the Board’s own

purposeful discriminatory conduct. In the District Court’s view, plain

tiffs had failed to show either discriminatory purpose or segregative

effect, or both, with respect to the Board’s challenged practices and

policies, which included faculty hiring and assignments, the use of

optional attendance zones and transfer policies, the location and con

struction of new and expanded school facilities, and the rescission of

certain prior resolutions recognizing the Board’s responsibility to eradi

cate racial separation in the public schools. The Court of Appeals

reversed, holding that at the time of Brown v. Board of Education, 347

U. S. 483 (Brown / ) in 1954, the Dayton Board had operated a racially

segregated, dual school system, that it was constitutionally required to

disestablish that system and its effects, that it had failed to discharge

this duty, and that the consequences of the dual system together with

the intentionally segregative impact of various practices since 1954, were

of systemwide import and an appropriate basis for a systemwide remedy.

Held:

1. On the record there is no basis for disturbing the Court of Appeals’

holding that at the time of Brown I the Dayton Board was intentionally

i

II DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

Syllabus

operating a dual school system in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause. Pp. 7-9.

2. Given the fact that a dual system existed in 1954, the Court of

Appeals also properly held that the Dayton Board was thereafter under

a continuing duty to eradicate the effects of that system, and that the

systemwide nature of the violation furnished prima facie proof that

current segregation in the Dayton Schools was caused at least in part

by prior intentionally segregative official acts. Part of the affirmative

duty imposed on a school board is the obligation not to take any action

that would impede the process of disestablishing the dual system and

its effects, Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U. S. 451, and here

the Dayton Board had engaged in many post-Brown I actions that had

the effect of increasing or perpetuating segregation. The measure of a

school board’s post-Brown 1 conduct under an unsatisfied duty to

liquidate a dual system is the effectiveness, not the purpose, of the

actions in decreasing or increasing the segregation caused by the dual

system. The Dayton Board had to do more than abandon its prior

discriminatory purpose, Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U. S. 189;

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U. S. 1. The Board

has had an affirmative responsibility to see that pupil assignment

policies and school construction and abandonment practices were not

used and did not serve to perpetuate or re-establish the dual system,

and has a “ heavy burden” of showing that actions that increased or con

tinued the effects of the dual system serve important and legitimate

ends. Pp. 9-12.

3. Nor is there any reason to fault the Court of Appeals’ finding,

after the remand of this case in Dayton Board of Education v. Brink-

man, 433 U. S. 406, that a sufficient case of current, systemwide effect

had been established. This was not a misuse of Keyes, supra, where

it was held that “ purposeful discrimination in a substantial part of a

school system furnishes a sufficient basis for an inferential finding of a

systemwide discriminatory intent unless otherwise rebutted” and that

“ given the purpose to operate a dual school system one could infer a

connection between such a purpose and racial separation in other parts

of the school system.” Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, ante,

at — . The Court of Appeals was also justified in utilizing the Dayton

Board’s failure to fulfill its affirmative duty and its conduct perpetuating

or increasing segregation to trace the current, systemwide segregation

back to the purposefully dual system of the 195Q’s and the subsequent

acts of intentional discrimination. Pp. 12-14.

583 F. 2d 243, affirmed.

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN in

Syllabus

W hite, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Brennan,

M arshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, JJ., joined. Stewart, J., filed a

dissenting opinion, in which Burger, C. J., joined. Powell, J., filed a

dissenting opinion. Rehnquist, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

Powell, J., joined.

NOTICE : This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication

in the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are re

quested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

United States, Washington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other

formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the pre

liminary print goes to press.

SUPEEME COUET OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 78-627

Dayton Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

v.

Mark Brinkman et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[July 2, 1979]

Mr. Justice W hite delivered the opinion of the Court.

This litigation has a protracted history in the courts below

and has already resulted in one judgment and opinion by this

Court, 433 U. S. 406 (1977). In its most recent opinion, the

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit approved

a systemwide plan for desegregating the public schools of

Dayton, Ohio. Brinkman v. Gilligan, 583 F. 2d 243 (CA6

1978). The Court of Appeals found that the Dayton Board

of Education had operated a racially segregated, dual school

system at the time of Brown v. Board of Education ( / ) , 347

U. S. 483 (1954), and that “ [t]he evidence of record demon

strates convincingly that defendants have failed to eliminate

the continuing systemwide effects of their prior discrimina

tion” and “actually have exacerbated the racial separation

existing at the time of Brown I.” 583 F. 2d, at 253. We

granted certiorari,---- U. S .------ (1979), and heard argument

in this case in tandem with Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, ante, p. ---- . We now affirm the judgment of the

Court of Appeals.

I

The public schools of Dayton are highly segregated by race.

In the year the complaint was filed, 43% of the students in

the Dayton system were black, but 51 of the 69 schools in the

2 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

system were virtually all-white or all-black,1 Brinkman v.

Gilligan, 446 F. Supp. 1232, 1237 (SD Ohio 1977). A number

of students in the Dayton system, through their parents,

brought this action on April 17, 1972, alleging that the Dayton

Board of Education, the State Board of Education, and the

appropriate local and state officials2 were operating a racially

segregated school system in violation of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The plaintiffs sought

a court order compelling desegregation. The District Court

1 The Court of Appeals set out the undisputed statistics:

“ ‘Enrollment data from the Dayton system reveals the substantial lack

of progress that has been made over the past 23 years in integrating the

Dayton school system. In 1951-52, of 47 schools, 38 had student enroll

ments 90 per cent or more one race (4 blacks, 34 whites). Of the 35,000

pupils in the district, 19 per cent were black. Yet over half of all black

pupils were enrolled in the four all black schools; and 77.6 per cent of all

pupils were assigned to virtual one race schools. “Virtual one race schools”

refers to schools with student enrollments 90 per cent or more one race.

In 1963-64, of 64 schools, 57 had student enrollments 90 per cent or more

one race (13 black, 44 white). Of the 57,400 pupils in the district, 27.8

per cent were black. Yet 79.2 per cent of all black pupils were enrolled

in the 13 black schools; and 88.8 per cent of all pupils were enrolled in

such one race schools.

“ ‘In 1971-72 (the year the complaint was filed), of 69 schools, 49 had

student enrollments 90 per cent or more one race (21 black, 28 white).

Of the 54,000 pupils, 42.7 per cent were black; and 75.9 per cent of all

black students were assigned to the 21 black schools. In 1972-73 (the year

the hearing was held) of 68 schools, 47 were virtually one race (22 black,

25 white); fully 80 per cent of all classrooms were virtually one race.

(Of the 50,000 pupils in the district, 44.6 per cent were black).

“ ‘Every school which was 90 per cent or more black in 1951-52 or

1963-64 or 1971—72 and which is still in use today remains 90 per cent or

more black. Of the 25 white schools in 1972-73, all opened 90 per cent

or more white and, if open, were 90 per cent or more white in 1971-72,

1963-64 and 1951-52.’ ” Brinkman v. Gilligan, 583 F. 2d 243, 254 (1978),

quoting Brinkman v. Gilligan, 503 F. 2d 684, 694—695 (CA6 1974).

2 In the last stages of this litigation, respondents did not press their

claims against the state officials. Only the Dayton Board and local officials

petitioned for writ of certiorari.

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 3

sustained their challenge, determining that certain actions by-

the Dayton Board amounted to a “cumulative” violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment. Pet. App. 12a-.3 The District

Court also approved a plan having limited remedial objectives.

The District Court’s judgment that the Board had violated

the Fourteenth Amendment was affirmed by the Court of

Appeals; but after twice being reversed on the ground that the

prescribed remedy was inadequate to eliminate all vestiges of

state-imposed segregation, the District Court ordered the

Board to take the necessary steps to assure that each school

in the system would roughly reflect the systemwide ratio of

black and white students. Pet. App. 103a.4 The Court of

Appeals then affirmed. Brinkman v. Gilligan, 539 F. 2d 1084

(CA6 1976).

We reversed the judgment of the Court of Appeals and

ordered the case remanded to the District Court for further

proceedings. 433 U. S. 406 (1977). In light of the District

3 The violation found by the District Court had three major components:

first, the marked racial separation of students, which the Board had made

no significant effort to alter; second, the utilization of optional attendance

zones, in some cases racially motivated and having significant segregative

effect in two high school zones; and third, the Board’s rescission of pre

viously adopted resolutions recognizing the Board’s role in racial segrega

tion and its responsibility to eradicate the existing pattern.

4 To preserve continuity, the court exempted enrolled high school students

for two academic years. And the court noted that it would evaluate on

a case-by-case basis any deviations from the target percentage. The court,

moreover, set down certain guidelines to be followed in achieving the

redistribution: (1) students would be permitted to attend neighborhood

walk-in schools in those neighborhoods where the schools were already

within the approved ratios; (2) students would be transported to the

nearest available school; and (3) no student would be transported further

than two miles or, if traveling that distance would take more time, for

longer than 20 minutes. The District Court appointed a master to

supervise the logistics of the plan. Certain other particulars were worked

out when the master’s report was filed. The plan has now been in effect

for three school years.

Court’s limited findings regarding liability,5 we concluded that

there was no warrant for imposing a systemwide remedy.

Rather, the District Court should have “determine[d] how

much incremental segregative effect these violations had on

the racial distribution of the Dayton school population as

presently constituted, when that distribution is compared to

what it would have been in the absence of such constitutional

violations. The remedy must be designed to redress that

difference, and only if there has been a systemwide impact

may there be a systemwide remedy.” Id., at 420. In view

of the confusion evidenced at various stages of the proceedings

regarding the scope of the violation established, we remanded

the case to permit supplementation of the record and specific

findings addressed to the scope of the remedy, id., at 418-419,

but allowed the existing remedy to remain in effect on remand

subject to further orders of the District Court, id., at 420-421.

The District Court held a supplemental evidentiary hear

ing, undertook to review the entire record anew, and entered

findings of fact and conclusions of law and a judgment dis

missing the complaint. In support of its judgment, the Dis

trict Court observed that, although various instances of pur

poseful segregation in the past evidenced “an inexcusable

history of mistreatment of black students,” 446 F. Supp., at

1237, plaintiffs had failed to prove that acts of intentional

segregation over 20 years old had any current incremental

segregative effects.6 The District Court conceded that the

5 The three parts of the violation found by the District Court are dis

cussed in n. 3, supra. Racial imbalance, we noted in Dayton I, is not

per se a constitutional violation, and rescission of prior resolutions pro

posing desegregation is unconstitutional only if the resolutions were re

quired in the first place by the Fourteenth Amendment. 433 U. S., at

413-414. Thus, the scope of liability extended no further than the use

of some optional zones, which apparently had a present effect only as to

certain high schools, and the rescission of the resolutions so far as they

pertained to these high schools. See id., at 412.

6 The District Court observed that “ [m]any of these practices, if they

4 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

Dayton schools were highly segregated but ruled that the

Board’s failure to alleviate this condition was not actionable

absent sufficient evidence that the racial separation had been

caused by the Board’s own purposeful discriminatory conduct,

In the District Court’s eyes, plaintiffs had failed to show either

discriminatory purpose or segregative effect, or both, with

respect to the challenged practices and policies of the Board,

which included faculty hiring and assignments, the use of

optional attendance zones and transfer policies, the location

and construction of new and expanded school facilities, and

the rescission of certain prior resolutions recognizing the

Board’s responsibility to eradicate racial separation in the

public schools.7

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 5

existed today, would violate the Equal Protection Clause.” Brinkman v.

Gilligan, 446 F. Supp. 1232, 1236 (SD Ohio 1977). The court identified

certain Board policies as being “ among” such practices: until at least

1934, black elementary students were kept separate from white students;

until approximately 1950 high school athletics were deliberately segregated

by race; and until about that same time black students at one high school

were ordered or induced to sit at the rear of classrooms and suffered other

indignities.

7 Reviewing the faculty assignment and hiring practices, the District

Court found that until at least. 1951 the Board’s policies had been inten

tionally segregative. But in that year the Board instituted a policy of

“ dynamic gradualism” and “by 1969 all traces of segregation were virtually

eliminated.” Id., at 1238-1239. Reasoning that the predominant factor

in the racial ident.ifiability of schools is the pupil population and not the

faculty, the court ruled that plaintiffs had not established that, past dis

crimination in faculty assignments had an incremental segregative effect.

Similarly, the court ruled that the plaintiff children had not- shown

that the Board’s use of attendance zones and transfers denied equal pro

tection. In certain instances, segregative intent had not been satisfactorily

demonstrated. In fact, the District Court reversed itself with respect to

the high school optional zones it had earlier held unconstitutional. In

other instances, current segregative effect had not been proved. Though

another high school, Dunbar, had been created and maintained until 1962

as a citywide black high school, the District Court found that because of

the increasing black population in that area Dunbar would have been

6 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

The Court of Appeals reversed. The basic ingredients of

the Court of Appeals’ judgment were that at the time of

Brown I, the Dayton Board was operating a dual school sys

tem, that it was constitutionally required to disestablish that

system and its effects, that it had failed to discharge this duty,

and that the consequences of the dual system, together with

the intentionally segregative impact of various practices since

1954, were of systemwide import and an appropriate basis for

a systemwide remedy. In arriving at these conclusions, the

Court of Appeals found that in some instances the findings of

the District Court were clearly erroneous and that in other

respects the District Court had made errors of law. 583 F. 2d,

at 247. Petitioners contend that the District Court, not the

Court of Appeals, correctly understood both the facts and the

law.

virtually all black by 1960 anyway. And though until the early 1950’s

black orphans had been bused past nearby white schools to all-black

schools, this “arguably” discriminatory conduct had not been shown by

“ objective proof” to have any continued segregative effect. Id., at 1241.

The court also looked to school construction and siting practices.

Although 22 of 24 new schools, 78 of 95 additions, and 26 of 26 portable

schools built or utilized by the Board between 1950 and 1972 opened

virtuaEy all black or all white, and though many of the accompanying

decisions appeared to be so without any rationale as to be “ haphazard,”

the District Court found that the plaintiffs had not shown purposeful

segregation. The court also refused to investigate whether the Board

had any legitimate grounds for the failure to close some schools and con

solidate others when enrollment declined in recent years. Though such a

course would have decreased racial separation and saved money, the court

found no evidence of discriminatory purpose in those facts. Nor did the

court see any hint of impermissible purpose in the Board’s decisions in

the 1940’s to supply school services for legally segregated housing projects

and to rent elementary school space in such projects.

Finally, the court held that the Board’s rescission of its earlier reso

lutions was not violative of the Fourteenth Amendment since, in light of

the court’s finding that the current segregation had no unconstitutional

origin, the Board had no constitutional obligation to adopt the resolutions

in the first place.

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 7

II

A

The Court of Appeals expressly held that, “ at the time of

Brown I, defendants were intentionally operating a dual

school system in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of

the fourteenth amendment,” and that the “ finding of the

District Court to the contrary is clearly erroneous.” 583 F.

2d, at 247 (footnote omitted). On the record before us, we

perceive no basis for petitioners’ challenge to this holding of

the Court of Appeals.8

Concededly, in the early 1950’s, “ 77.6 percent of all students

attended schools in which one race accounted for 90 percent

or more of the students and 54.3 percent of the black students

were assigned to four schools that were 100 percent black.”

Id., at 248-249. One of these schools was Dunbar High

School, which, the District Court found, had been established

as a districtwide black high school with an all-black faculty

and a black principal, and remained so at the time of Brown I

and up until 1962. 446 F. Supp., at 1246. The District Court

also found that “among” the early and relatively undisputed

acts of purposeful segregation was the establishment of Gar

field as a black elementary school. Id., at 1236-1237. The

Court of Appeals found that two other elementary schools

were, through a similar process of optional attendance zones

and the creation and maintenance of all-black faculties, inten

tionally designated and operated as all-black schools in the

8 We have no quarrel with our Brother Stewart’s general conclusion

that there is great value in appellate courts showing deferrence to the fact

finding of local trial judges. Post, a t ---- . The clearly erroneous standard

serves that purpose well. But under that standard, the role and duty of

the Court of Appeals are clear: it must determine whether the trial court’s

findings are clearly erroneous, sustain them if they are not, but set them

aside if they are. The Court of Appeals performed its unavoidable duty in

this case and concluded that the District Court had erred. Differing with

our dissenting Brothers, we see no reason on the record before us to upset

the judgment of the Court of Appeals in this respect.

1930’s, in the 1940’s, and at the time of Brown I. 583 F. 2d, at

249, 250-251. Additionally, the District Court had specifically

found that in 1950 the faculty at 100% black schools was

100% black and that the faculty at all other schools was 100%

white. 446 F. Supp., at 1238.

These facts, the Court of Appeals held, made clear that the

Board was purposefully operating segregated schools in a sub

stantial part of the district, which warranted an inference and

a finding that segregation in other parts of the system was

also purposeful absent evidence sufficient to support a finding

that the segregative actions “were not taken in effectuation of

a policy to create or maintain segregation” or were not among

the “ factors . . . causing the existing condition of segregation

in these schools.” Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 413 IT. S. 189,

214 (1973); see id., at 203; Columbus, ante, at ---- . The

District Court had therefore ignored the legal significance of

the intentional maintenance of a substantial number of black

schools in the system at the time of Brown I. It had also

ignored, contrary to Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U. S. 1, 18 (1971), the significance of pur

poseful segregation in faculty assignments in establishing the

existence of a dual school system; 9 here the “purposeful

8 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

9 We do not deprecate the relevance of segregated faculty assignments

as one of the factors in proving the existence of a school system that is dual

for teachers and students; but to the extent that the Court of Appeals

understood Sivann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U. S.

1 (1971), as holding that faculty segregation makes out a prima facie case

not only of intentionally discriminatory faculty assignments contrary to

the Fourteenth Amendment but also of purposeful racial assignment of

students, this is an overreading of Swann.

The Court of Appeals also held that the District Court had not given

proper weight to Oliver v. Michigan State Board of Education, 508 F. 2d

178, 182 (CA6 1974), cert, denied, 421 U. S. 963 (1975), where the Court

of Appeals had held that “ [a] presumption of segregative purpose arises

when plaintiffs establish that the natural, probable, and foreseeable result of

public official’s action or inaction was an increase or perpetuation of public

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 9

segregation of faculty by race was inextricably tied to racially

motivated student-assignment practices.” 583 F. 2d, at 248.

Based on its review of the entire record, the Court of Appeals

concluded that the Board had not responded with sufficient

evidence to counter the inference that a dual system was in

existence in Dayton in 1954. Thus, it concluded that the

Board’s “ intentional segregative practices cannot be confined

in one distinct area” ; they “ infected the entire Dayton public

school system.” Id., at 252.

B

Petitioners next contend that, even if a dual system did

exist a quarter of a century ago, the Court of Appeals erred

in finding any widespread violations of constitutional duty

since that time.

Given intentionally segregated schools in 1954, however,

the Court of Appeals was quite right in holding that the Board

was thereafter under a continuing duty to eradicate the effects

of that system, Columbus, ante, at ------------- , and that the

systemwide nature of the violation furnished prima facie proof

that current segregation in the Dayton schools was caused at

least in part by prior intentionally segregative official acts.

Thus, judgment for the plaintiffs was authorized and required

absent sufficient countervailing evidence by the defendant

school segregation,” and that “ [t]he presumption becomes proof unless

the defendants affirmatively establish that their action or inaction was a

consistent and resolute application of racially neutral policies.” We have

never held that as a general proposition the foreseeability of segregative

consequences makes out a prima facie case of purposeful racial discrimina

tion and shifts the burden of producing evidence to the defendants if they

are to escape judgment; and even more clearly there is no warrant in our

cases for holding that such foreseeability routinely shifts the burden of

persuasion to the defendants. Of course, as we hold in Columbus today,

ante, at -— , proof of foreseeable consequences is one type of quite relevant

evidence of racially discriminatory purpose, and it may itself show a failure

to fulfill the duty to eradicate the consequences of prior purposefully

discriminatory conduct. See supra, at •— .

school officials. Keyes, supra, at 211; Swann, supra, at 26.

At the time of trial, Dunbar High School and the three black

elementary schools, or the schools that succeeded them, re

mained black schools; and most of the schools in Dayton were

virtually one-race schools, as were 80% of the classrooms.

“ ‘Every school which was 90 percent or more black in 1951-52

or 1963-64 or 1971-72 and which is still in use today remains

90 percent or more black. Of the 25 white schools in 1972-73,

all opened 90 percent or more white and, if opened, were 90

percent or more white in 1971-72, 1963-64 and 1951-52.’ ”

583 F. 2d, at 254 (emphasis in original), quoting Brinkman v.

Gilligan, 503 F. 2d 683, 694-695 (CA6 1974). Against

this background, the Court of Appeals held “ [t]hat the evi

dence of record demonstrates convincingly that defendants

have failed to eliminate the continuing systemwide effects of

their prior discrimination and have intentionally maintained

a segregated school system down to the time the complaint

was filed in the present case.” 583 F. 2d, at 253. At the very

least, defendants had failed to come forward with evidence to

deny “that the current racial composition of the school popu

lation reflects the systemwide impact” of the Board’s prior

discriminatory conduct. Id., at 258.

Part of the affirmative duty imposed by our cases, as we

decided in Wright v. Council oj City of Emporia, 407 U. S.

451 (1972), is the obligation not to take any action that would

impede the process of disestablishing the dual system and its

effects. See also United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, 407 U. S. 484 (1972). The Dayton Board,

however, had engaged in many post-Brown actions that had

the effect of increasing or perpetuating segregation. The Dis

trict Court ignored this compounding of the original constitu

tional breach on the ground that there was no direct evidence

of continued discriminatory purpose. But the measure of the

post-Brown conduct of a school board under an unsatisfied

duty to liquidate a dual system is the effectiveness, not the

10 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 11

purpose, of the actions in decreasing or increasing the segre

gation caused by the dual system. Wright, supra, at 460, 462;

Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U. S.

33, 37 (1971); see Washington v. Davis, 426 U. S. 229, 243

(1976). As was clearly established in Keyes and Swann, the

Board had to do more than abandon its prior discriminatory

purpose. 413 U. S., at 200-201, n. 11; 402 U. S., at 28. The

Board has had an affirmative responsibility to see that pupil

assignment policies and school construction and abandonment

practices “are not used and do not serve to perpetuate or

re-establish the dual school system,” Columbus, ante, a t -----,

and the Board has a “ ‘heavy burden’ ” of showing that actions

that increased or continued the effects of the dual system

serve important and legitimate ends. Wright, supra, at 467,

quoting Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S. 430, 439

(1968).

The Board has never seriously contended that it fulfilled its

affirmative duty or the heavy burden of explaining its failure

to do so. Though the Board was often put on notice of the

effects of its acts or omissions,10 the District Court found that

“ with one [counterproductive] exception . . . no attempt was

made to alter the racial characteristics of any of the schools.”

446 F. Supp., at 1237. The Court of Appeals held that far

from performing its constitutional duty, the Board had en

gaged in “post-1954 actions which actually have exacerbated

the racial separation existing at the time of Brown I.” 583

F. 2d, at 253. The court reversed as clearly erroneous the

District Court’s finding that intentional faculty segregation

had ended in 1951; the Court of Appeals found that it had

10 The Board heard from the local NAACP and other community groups,

the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, the Ohio State Depart

ment of Education, and a citizens advisory group the Board had appointed;

at times the Board itself expressed its recognition of the problem and of

its responsibility, though utimately it did nothing. 446 F. Supp., at 1251—

1252.

12 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

effectively continued into the 1970’s.11 12 This was a systemwide

practice and strong evidence that the Board was continuing

its efforts to segregate students. Dunbar High School re

mained as a black high school until 1962, when a new Dunbar

High School opened with a virtually all-black faculty and

student body. The old Dunbar was converted into an ele

mentary school to which children from two black grade schools

were assigned. Furthermore, the Court of Appeals held that

since 1954 the Board had used some “optional attendance

zones for racially discriminatory purposes in clear violation

of the Equal Protection Clause.” Id., at 255. The District

Court’s finding to the contrary was clearly erroneous.11 At

the very least, the use of such zones amounted to a perpetua

tion of the existing dual school system. Likewise, the Board

failed in its duty and perpetuated racial separation in the

schools by its pattern of school construction and site selection,

recited by the District Court, see n. 7, supra, that resulted in

22 of the 24 new schools built between 1950 and the filing of

the complaint opening 90% black or white. The same pat

11 Under the policy of “dynamic gradualism” instituted in 1951, see n. 7,

supra, black teachers were assigned to white or mixed schools when the

surrounding communities were ready to accept black teachers, and white

teachers who agreed were assigned to black schools. App. 182-Ex. By

1969 each school in the system had at least one black teacher. The Dis

trict Court apparently did not think the post-1951 policy was purposeful

discrimination. 446 F. Supp., at 1238-1239. We think the Court of

Appeals was completely justified in finding that conclusion to be clearly

erroneous on the undisputed facts. As late as the 1968-1969 school year,

the Board assigned 72% of all black teachers to schools that were 90%

or more black, and only 9% of white teachers to such schools. And faculty

segregation disappeared completely only after efforts of the Department

of Health, Education, and Welfare under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. See 446 F. Supp., at 1238.

12 The Court of Appeals found that the District Court had committed

clear error in reversing its earlier findings of purpose as to certain optional

zones, which the Court of Appeals had earlier affirmed and this Court

had not set aside. 583 F. 2d, at 255.

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 13

tern appeared with respect to additions of classroom space

made to existing schools. Seventy-eight of a total of 86 addi

tions were made to schools that were 90% of one race. We

see no reason to disturb these factual determinations, which

conclusively show the breach of duty found by the Court of

Appeals.

C

Finally, petitioners contend that the District Court cor

rectly interpreted our earlier decision in this litigation as

requiring respondents to prove with respect to each individual

act of discrimination precisely what effect it has had on cur

rent patterns of segregation.13 This argument results from a

misunderstanding of Dayton I, where the violation that had

then been established included at most a few high schools.

See Columbus, ante, a t ---- n. 5 and------; nn. 3 and 5, supra.

We have found no reason to fault the Court of Appeals’ find

ings after our remand that a sufficient case of current, system-

wide effect had been established. In reliance on its decision

in Columbus, the Court of Appeals held that:

“First, the dual school system extant at the time of

Brown I embraced 'a systemwide program of segregation

affecting a substantial portion of the schools, teachers,

and facilities’ of the Dayton schools, and, thus, clearly

had systemwide impact. . . . Secondly, the post-1954

failure of defendants to desegregate the school system in

contravention of their affirmative constitutional duty

obviously had systemwide impact. . . . The impact of

defendants’ practices with respect to the assignment of

faculty and students, use of optional attendance zones,

school construction and site selection, and grade structure

13 Petitioners also contend that the respondent children have failed to

establish their standing to bring this action. This challenge is dependent

on petitioners’ major contentions, for if the Court of Appeals was correct

that the current, systemwide segregation is a result of past unlawful con

duct then respondents, as students in the system, clearly have standing.

and reorganization clearly was systemwide in that actions

perpetuated and increased public school segregation in

Dayton.” 583 F. 2d, at 258, quoting Keyes, supra, at 201.

As we note in Columbus today, this is not a misuse of

Keyes, “where we held that purposeful discrimination in a

substantial part of a school system furnishes a sufficient basis

for an inferential finding of a systemwide discriminatory in

tent unless otherwise rebutted, and that given the purpose to

operate a dual school system one could infer a connection

between such a purpose and racial separation in other parts

of the school system.” Columbus, ante, at -----. See also

Swann, supra, at 26. The Court of Appeals was also quite

justified in utilizing the Board’s total failure to fulfill its

affirmative duty—and indeed its conduct resulting in increased

segregation—to trace the current, systemwide segregation

back to the purposefully dual system of the 1950’s and to

the subsequent acts of intentional discrimination. See

supra, a t ---- ; Columbus, ante, a t ----- ; Keyes, supra, at 211;

Swann, supra, at 21, 26-27.

Because the Court of Appeals committed no prejudicial

errors of fact or law, the judgment appealed from must be

affirmed.

14 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

So ordered.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 78-627

Dayton Board of Education

et al., Petitioners,

v.

Mark Brinkman et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[July 2, 1979]

M b. Justice R ehnquist, with whom M e. Justice Powell

joins, dissenting.

For the reasons set out in my dissent in Columbus Board

of Education v. Penick, No. 78-610 (1979), I cannot join the

Court’s opinion in this case. Both the Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit and this Court used their respective Colum

bus opinions as a roadmap, and for the reasons I could not

subscribe to the affirmative duty, the foreseeability test, the

cavalier treatment of causality, and the false hope of Keyes

and Swann rebuttal in Columbus, I cannot subscribe to them

here. Little would be gained by another “blow-by-blow”

recitation in dissent of how the Court’s cascade of presump

tions in this case sweeps away the distinction between de

facto and de jure segregation.

In its haste to affirm the Court of Appeals, the Court barely

breaks stride to note that there were some “overreading of

Swann” in the Court of Appeals conclusion that there was a

“dual” school system at the time of Brown I, and that the

court had the wrong conception of segregative intent, i. e., the

mysterious Oliver standard which this Court thinks the Court

of Appeals talks a lot about but never really applies. Ante,

at 8-9, n. 9. But as the Court more candidly recognizes in this

case, the affirmative duty renders any discussion of segrega

tive intent after 1954 gratuitous anyway. The Court is also

more honest about the stringency of the standard by which

all post-1954 conduct is to be judged: “The Board has a

2 DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN

‘ “heavy burden” ’ of showing that actions that increased

or continued the effects of the dual school system serve

important and legitimate ends.” Ante, at 11 (emphasis

added).

I think that the Columbus and Dayton District Court

opinions point out the limitation of my Brother Stewart’s

perception of the proper roles of the trial judge and reviewing

courts. That this and other appellate courts must defer to

the factfindings of trial courts is unexceptionable. With the

aid of this observation, he concludes that the Court of Ap

peals should be affirmed in Columbus, insofar as it agreed

with the District Court there, and should be reversed here

because it upset the District Court’s conclusion that there was

no warrant for a desegregation remedy. But even a casual

reading of the District Court opinions makes it very clear

that the primary determinants of the different results in these

two cases were two totally different conceptions of the law

and methodology that govern school desegregation litigation.

The District Judge in Dayton did not employ a post-1954

“affirmative duty” test. Violations he did identify were

found not to have any causal relationship to existing condi

tions of segregation in the Dayton school system. He did

not employ a foreseeability test for intent, hold the school

system responsible for residential segregation, or impugn the

neighborhood school policy as an explanation for some exist

ing one race schools. In short, the Dayton and Columbus

district judges had completely different ideas of what the law

required. As I am sure my Brother Stewart agrees, it is for

reviewing courts to make those requirements clear.

Thus the District Court opinions in these two cases demon

strate dramatically the hazards presented by the laissez-faire

theory of appellate review in school desegregation cases. And

I have no doubt that the Court of Appeals’ heavy-handed

approach in this case is to some degree explained by the per

ceived inequity of imposing a systemwide racial-balance

DAYTON BOARD OF EDUCATION v. BRINKMAN 3

remedy on Columbus while finding no violation in Dayton.*

The simple meting out of equal remedies, however, is not by

any means “equal justice under law.”

*The Court of Appeals did not even remand to allow the Dayton school

authorities the opportunity to show that a more limited remedy was war

ranted, even though the Court of Appeals made findings of fact with re

spect to liability that had never been made before by any court in this

long litigation, and therefore were never part of a remedy hearing. This

doubtlessly reflects the Court of Appeals’ honest appraisal of the futility of

attempts at Swann rebuttal by a School Board.