Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Motion in Limine and Motion for Recusal

Public Court Documents

November 20, 1980

15 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs' Opposition to Defendants' Motion in Limine and Motion for Recusal, 1980. 137f6a7a-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a21acf46-cd52-438b-8cc3-6c2765493e01/plaintiffs-opposition-to-defendants-motion-in-limine-and-motion-for-recusal. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY LL. BOLDEN, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

VS. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MORILE, et al., )

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS

MOTION IN LIMINE AND MOTION FOR RECUSAL

Plaintiffs, through their undersigned counsel, submit

this written opposition to the defendants' two motions in

limine and motion for recusal, filed on or about November

14, 1980. We believe that the motions are patently frivolous,

that they attempt to reargue questions decided when this Court

denied the City's motion to dismiss, and that their clear

underlying purpose is to politicize this case and embarrass

this Court.

The First and Second Motions in Limine

Defendants argued in their motion to dismiss on remand

that the Supreme Court had considered all the evidence in

the record and had concluded that it failed to prove the

requisite racial intent. This Court disagreed, denying the

motion to dismiss and scheduling proceedings to receive

additional evidence, based on its understanding of the

Supreme Court's mandate and the plurality opinion that the

evidence should be reviewed under the correct legal standards.

Defendants now recast this same unsuccessful argument

by contending that the plurality opinion precludes this

Court from considering anew any of the evidence previously

presented. We have difficulty believing that defendants’

counsel present this new contention seriously. It contra-

venes the aleay remand instructions of the plurality, as this

Court has construed them, as well as firmly established

principles of law governing remand proceedings.

To begin with, if it were true that the Supreme Court

plurality had already reviewed all the evidence previously

presented and had decided that it failed to meet the eviden-

tiary standard of intent, then the City's motion to dismiss

should have been granted. There would be nothing left for

this Court to consider under Plaintiffs' fourteenth amendment

claims. This Court has already ruled that the plurality

intended that the evidence be reviewed under correct legal

standards. Because this point is settled, to exclude con-

sideration of the existing evidence of record squarely con-

travenes the Supreme Court's remand instructions and the

teachings of the plurality opinion,

The oft-repeated language of the plurality opinion relied

on by Defendants, ''that the evidence in the present case

fell far short" of proving intent, plainly means not that the

existing evidence was sufficient to disprove racial intent,

but that it was not enough to prove racial intent. Thus the

plurality means that this Court should point to evidence in

addition to that which it relied on in its Zimmer analysis to

sustain a finding of racial intent. This Court would squarely

violate the plurality's instructions if it ignored the evidence

of legislative activities in the 1960's and 1970's referred to

in footnote 21. Similarly, it would violate the plurality's

instructions if evidence produced under the standards of White

v. Regester and Zimmer v. McKeithen were ignored in the intent

inquiry. The plurality stated that White v. Regester type evi-

dence is ''consistent with" the principles of Washington v. Davis,

Slip Op. at 12, and that Zimmer evidence 'may afford some evi-

dence of a discriminatory purpose," though not by itself. Slip

Op. at 16, Indeed, according to the plurality, all the

evidence which led this Court to conclude that the at-

large election system had an adverse racial effect on

black voters provides "an important starting point' for the

intent inquiry. Slip Op. at 13. And, although the existing

evidence of past official discrimination against blacks is

relevant to the ir ~ inquiry unc : rlingto eights el nt to the intent inquiry under the Arlington Heights

analysis, Plaintiffs must show the connection between those

prior official practices and present day discrimination.

Siip Op, at 12, 13, 17. 8o, once this Court has rejected the

argument that the Supreme Court has addressed and decided

the intent question on the evidence, it is unmistakably clear

that the plurality's opinion requires this Court to review all

of the evidence previously presented under the correct legal

standards.

As learned counsel for Defendants know, it is a firmly

established rule of law that when a case is tried before the

court without a jury and subsequent rulings require reconsid-

eration or a new trial, the remand proceedings should be based

on evidence already presented to the trial judge, and whether

or not additional evidence may be submitted is subject to the

sound discretion of the judge. Hennessey v. Schmidt, 583 F.2d

302, 304-035, 306-07 (7th Cir. 1978) ; Rule v, International

Association of Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Ironworkers

i

568 F.2d 538, 569 (Sth Cir, 1977); Golf Cicy, Inc. v. Wilson

Sporting Goods Co., 555 F.24 426, 438 n.20 (5th Cir. 1977);

Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 534 F.24 825, 833-34 (8th Cir.

1977); Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333, 347 (10th

Cir. 1975); Rewis v, United States, 369 F.2d 595, 603 (5th

Cir. 1966), on remand, 304 F.Supp. 410 (5.0. Ga. 1969),

rev'd and remanded, 445 F.2d 1303, 1306 (5th Cir. 1971). See

also Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. v. Village of

Arlington Heights, 469 F.Supp. 836, 849 (N.D. Ill. 1979), on

remand fxom 538 F.24 1283 (7c¢h Cir. 1977), cert.denied, 434

U.5. 1023 (1978),

This rule is also dictated by Rule 539(a), F.R.C.P.:

On a motion for a new trial in an

action tried without a jury, the

court may open the judgment if one

has been entered, take additional

testimony, amend findings of fact

and conclusions of law or make new

findings and conclusions, and direct

the entry of a new judgment.

Hennessey v. Schmidt, supra, is close on point. There a #.

breach of a sales contract was alleged, and the court of

appeals vacated the judgment of the district court and remanded

the case for "further proceedings." 583 F.2d at 304. The

a5.

court of appeals had determined that the district court,

who had tried the case without a jury, had erroneously

applied a "conclusive proof" standard to the evidence rather

than the "preponderance of the evidence" standard, as well

as an improper legal test of proximate cause. Id. On remand,

the district court decided for the plaintiff without taking

any new evidence, and on the second appeal, the defendant con-

tended that the "further proceedings' instructions from the

first appeal required that additional testimony be taken before

judgment on remand was entered. 583 F.2d at 306-07. The court

of appeals disagreed, saying that "[a] new trial, or the taking

of additional testimony, was neither required nor appropriate."

583 F.2d at 307. The 7th Circuit did intimate that additional

testimony would have been appropriate if there had been some

evidence in the original trial subject to challenge on the

basis of the credibility, integrity or competence of a witness

or if the original appellate opinion had suggested that addi-

tional evidence under the correct legal standard might be

appropriate. Id. In the instant case, application of these

principles would seem to dictate the procedure this Court

has already ordered; that is, review by the trial judge of the

evidence already presented plus the consideration of any addi-

tional testimony or documentary evidence that the parties might

<

wish to present on the intent issue. Additional evidence

seems particularly appropriate here, in light of the pre-

viously discussed instructions of the Supreme Court. Another

reason for taking additional evidence is that, subsequent

to the original trial of this case, intervening decisions

of the Supreme Court have refined and added to the criteria

for proving discriminatory intent, as the City Defendants

pointed out to the Supreme Court in their brief for the

appellants, p. 25 n.28.

The Motion for Recusal

A telling feature of the motion for recusal is that

it cites no statutory or other legal authority. Counsel

for Defendants are well aware of the statutory bases for recusal

of a district judge. See Potashnick v. Port City Construction

Co., F.24 (5th Cir. 1980). Counsel surely must know

that the sole ground they cite for recusal, that Your Honor

has made a previous ruling that the at-large City elections

were maintained for a racially discriminatory purpose, is

legally insufficient to require or permit recusal. It has

been held time and time again that prior judicial rulings

cannot be made the basis of a district judge's recusal, but

that the "determination should ... be made on the basis of

conduct extra-judicial in nature as distinguished from con-

duct within a judicial context." Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 517 F.2d 1044, 1052 (5th

Cir. 1975), cext.denled, 425 U.S5. 944 (1976); accord, Berger

Vv. Unlced States, 255 U.S. 22 (1921); Potashnick v. Port City

Construction Co., supra; Hepperle v. Johnson, 590 F.2d 609,

613 (5th Cir. 1979); Parrish v. Board of Commissioners of

Alabama State Bar, 525 F.2d 98, 100 (5ch Cir. 1975) (en banc),

cert.denied, sub nom., Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 425 U.S. 944 (1976); Bowling v. Matthews,

511 7.24 112, 114 (5th Cir, 1975); Oliver v, Michigan State

Board of Educacion, 508 F.24 178, 180 (6th Cir, 1974), cert

denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975); Galella v. Onassis, 487 F.24

986 (2d Cir. 1973); United States v. Thompson, 483 F.2d 527,

528 (3rd Cir. 1973); Plaquemines Parish School Board wv.

United States, 415 F.2d 817, 325 (5th Cir. 1969). This rule

applies whether the Court is considering recusal under 28

U.8.C. 8144 or 283 U.S.C. 5455. Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, supra, 517 F.2d at 1052.

The rule that a district judge should not recuse himself

on the basis of judicial expressions of opinion has been held

to include the situation where he or she is required to retry

or reconsider a case in which he or she had previously ruled.

For example, Circuit Judge, now Chief Justice, Warren

Burger, held in Coppedge v. United States, 311 F.2d 1278,

133 (D.C, Civ. 1962), cert.denied, 373 U.S. 946 (1963),

that the trial judge properly refused to disqualify himself

in the second trial of a criminal case, even though the

defendant claimed that the judge had formed a personal bias

and opinion of his guilt against him in the first trial. In

Oliver v. Michigan State Board of Education, supra, the state

defendants asked the district judge to disqualify himself on

the ground that he

held "an unshakable conviction"

that there is no distinction

between de facto and de jure

segregation for constitutional

purposes; that the relief granted

was biased in favor of the black

plaintiffs and prejudicial to

poor whites; that personal bias

for the plaintiffs was demonstrated

by the manner in which the parties

were characterized and the treat-

ment accorded the parties, counsel

and witnesses; that an irrelevant

and erroneous finding was made

with regard to certain advice

given by the defendants' attorney;

that a Motion for Protective Order

filed by plaintiffs was given

improper treatment; and that there

was undue delay in holding the trial

on the merits of the case.

308 F.2d at 180. Treating all the alleged facts as true,

the Sixth Circuit nevertheless held that they did not suffice

to support a claim of personal as distinguished from judicial

bias. Similarly, the Fifth Circuit held that Judge

Christenberry had properly refused to recuse himself when

the Plaquemines Parish School Board claimed he was biased

against them based on "repeated conclusions of bias

supported by no facts other than a recitation of adverse

rulings and findings of fact." 415 F.2d ac 825.

Indeed, for a district judge to recuse himself solely

because he had previously made legal or factual findings

which were subsequently reversed and remanded for reconsidera-

tion would defeat the purpose of Rule 59 and the many cases

which say that evidence previously presented ought not be

repeated when the trial was without a jury. Only the judge

who tried the case originally will have heard the testimony

of all the witnesses and the explanation of the documentary

evidence. Rule 52, F.R.C.P., states that "due regard shall

be given to the opportunity of the trial court to judge of

the credibility of the witnesses." Moreover, the logical

extension of a rule that required or permitted a trial judge to

recuse himself after reversal on appeal would be a requirement

that judges who have made findings of fact and conclusions of law

in a bench trial recuse themselves if they grant a new trial

prior to appeal, See Rule 59. This illustrates how nonsensi-

«10-

cal is the defendants' motion for recusal in the instant

case.

In addition, it may well be that for Your Honor to

disqualify himself in the circumstances and procedural

history of this case would work a denial of due process

for the Plaintiffs. This Court has already ruled that the

Supreme Court has not addressed the question of whether the

evidence supports a finding of racial intent in the main-

tenance of at-large elections. Consequently, if it is true,

as Defendants have alleged in their motion for recusal, that

Your Honor has already held that the City of Mobile's at-large

form of government was being maintained for the purpose of

discriminating against black voters, recusal would effectively

set aside that finding without it ever having been disapproved.

The reconsideration ordered by the Supreme Court and the Fifth

Circuit could entail only reaffirmation and explication of

this Court's previous findings, if the Defendants' interpreta-

tion of the original district court opinion is correct. So,

1f this Court's original finding of racial intent in the

maintenance of at-large elections is based on misunderstanding

of the correct legal criteria, there can be no credible claim

of even judicial predisposition. On the other hand, if this

Court did understand the correct legal principles and based

ay Be

such a finding thereon, the Plaintiffs are entitled to

reentry of judgment in their favor. Only Your Honor can make

this determination, and if you recuse yourself, the Plaintiffs

would never have the opportunity for a judicial enforcement

of findings of fact and conclusions of law which entitle them

to relief and which never have been squarely rejected on appeal.

That, we suggest, would be a clear violation of due process.

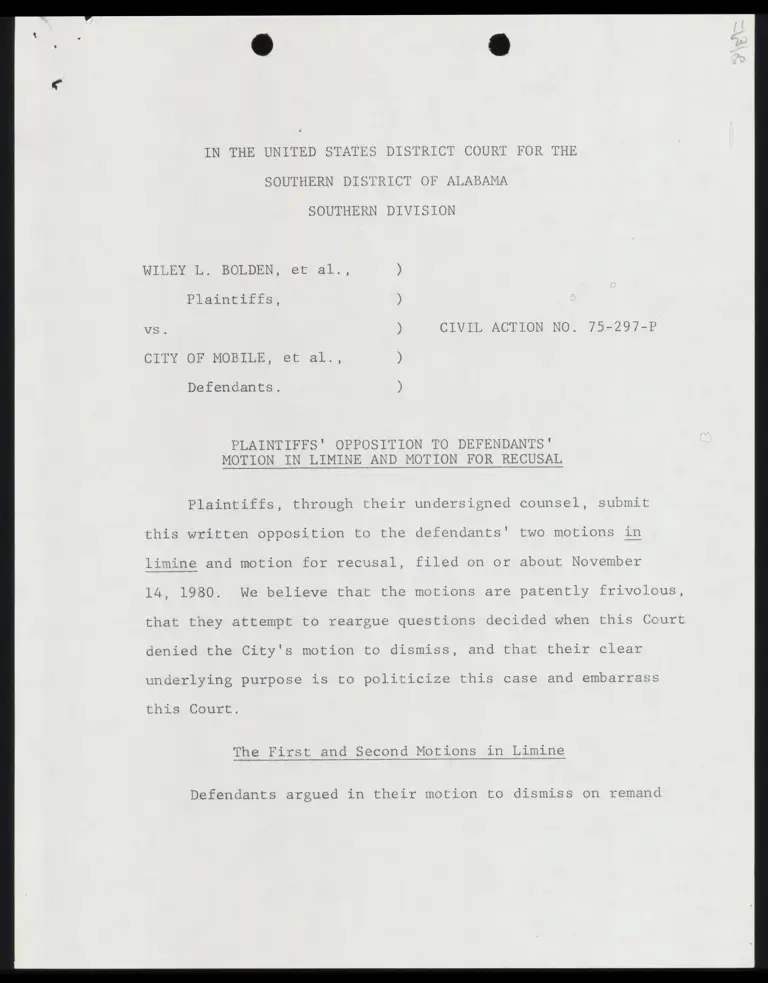

By any measure, the defendants' motion for recusal is

frivolous. It makes no attempt whatsoever to cite even a single

statutory or case authority to support its provocative request.

W 2 can only conclude that the motion is politically intended.

As we have demonstrated, the law leaves Your Honor little or

no choice but to deny the motion to recuse. We can anticipate

that your ruling on the motion will evoke additional personal

attacks on Your Honor in the local media. See Exhibit A. It

will be difficult for the public to understand the difference

between a personal non-judicial bias which warrants recusal

and the judicial bias alleged by Defendants which as a matter

of law does not permit recusal. Consequently, we think that

the filing of a bare allegation of judicial bias, without

reference to any legal support and without any attempt to

comply with the affidavit requirements provided by statute,

is deplorable. See Ethical Consideration 8-6, Code of Pro-

fessional Responsibility of the Alabama State Bar (1974).

32

The Defendants

and their motion for

Respectfully submitted this cil

CERTIFICATE

Conclusion

first and second motions

recusal should be denied.

in limine

day of November, 1980.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 Van Antwerp Bldg.

F. O.: Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

BY:

Z/ Ci fe

At Az aiid.

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

YLARRY T. MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL

Reeves & Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Legal Defense Fund

Suite 2030

10 Columbus C

New York, New York 100:

ircle

p

d

O

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on this

1980, a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS' OPPOSITION TO

DANTS' MOTION IN LIMINE AND MOTION FOR RECUSAL

~13-

( day of November,

DEFEN-

was served

upon counsel of record: Charles B. Arendall, Jr., Esgqg.,

William C. Tidwell, III, Esq., Hand, Arendall, Bedsole,

Greaves & Johnston, P. 0. Box 123, Mobile, Alabama 36601;

Barry Hess, Esq,, City Attorney, City Hall, Mobile, Alabama

36602; Charles S. Rhyne, Esq. and William S. Rhyne, Esq.,

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 800, Washington, D.C.

20036; Paul F. Hancock, Esq. and J. Gerald Hebert, Esq.,

Civil Rights Division, Department of Justice, 10th and

Constitution Avenue, N.W,, Washington, D.C. 20530 and Drew

S. Days, III, Esq., Assistant Attorney General, Department

of Justice, Washington, D.C. 20530, by depositing same in

the United States mail, postage prepaid.

oz 4 : 7 \; oA Y 7 ASS

ATTORNEY FOR

| /

Vv

/

/

‘ FS L. {

PLAINTIFFS

oy Xu

Thursday, Nov. 20, 1980

LAM etn

! @

Pittman should orant

- i BO AR ATTN Ah Pp. city recusal rec i Lest

1).8. District Judge Virgil

Pittman of Mobile, who considers

himself an expert on matters of

discrimination and prejudice,

should not hesitate to grant a City

of Mobile motion asking that he

recuse himself from the retrial of

the landmark change of gov-

ernment suit he has been handl-

ing for several years.

The motion makes the simple

but extremely valid point that the

trial judge has already reached a

decision in the case. All he is now

doing is attempting to justify his

prejudice in a manner which

might win U.S. Supreme Court

approval.

" Pittman has done everything in

his power to force the city and

other governmental entities in

this area to bend to his personal

wishes as outlined in a series of

orders dating back to 1976. Even

after being reversed by the

Supreme Court and the 5th U.S.

Circuit Court of Appeals, the

Mobile district judge has time

g

r

a

t

e

r

after time refused to accept such

setbacks. He plods forward with a

single-minded determination to

have his decrees implemented.

1

The City of Mobile is therefore

confronted with what will amount

to a kangaroo court proceeding

following which a new but onl

slightly modified ruling will be

issued by Pittman.

Then 1t will be another [Ying and

costly appeal process back to the

Supreme Court — coupled with

another period of confusion as to

the lei of new elections

which by next year will be four

years overdue.

We would ap) that the judge in

a rare show of fairness might

grant the city’s motion for him to

withdraw from the case. But

based on past performance, we

are not too optimistic.

Federal judges with lifetime

appointments frequently fail to

consider equity and fairness as

they look down {from their ivory

lowers.

EXHIBIT A