Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees of American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, Inc., League of Women Voters of the United States; And, League of Women Voters Education Fund

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Motion for Leave to File Brief and Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees of American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, Inc., League of Women Voters of the United States; And, League of Women Voters Education Fund, 1985. 0705da42-d992-ee11-be37-6045bddb811f. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a2d081df-1692-4252-bc9c-48eaa7b00afe/motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-of-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellees-of-american-civil-liberties-union-foundation-inc-league-of-women-voters-of-the-united-states-and-league-of-women-voters-education-fund. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

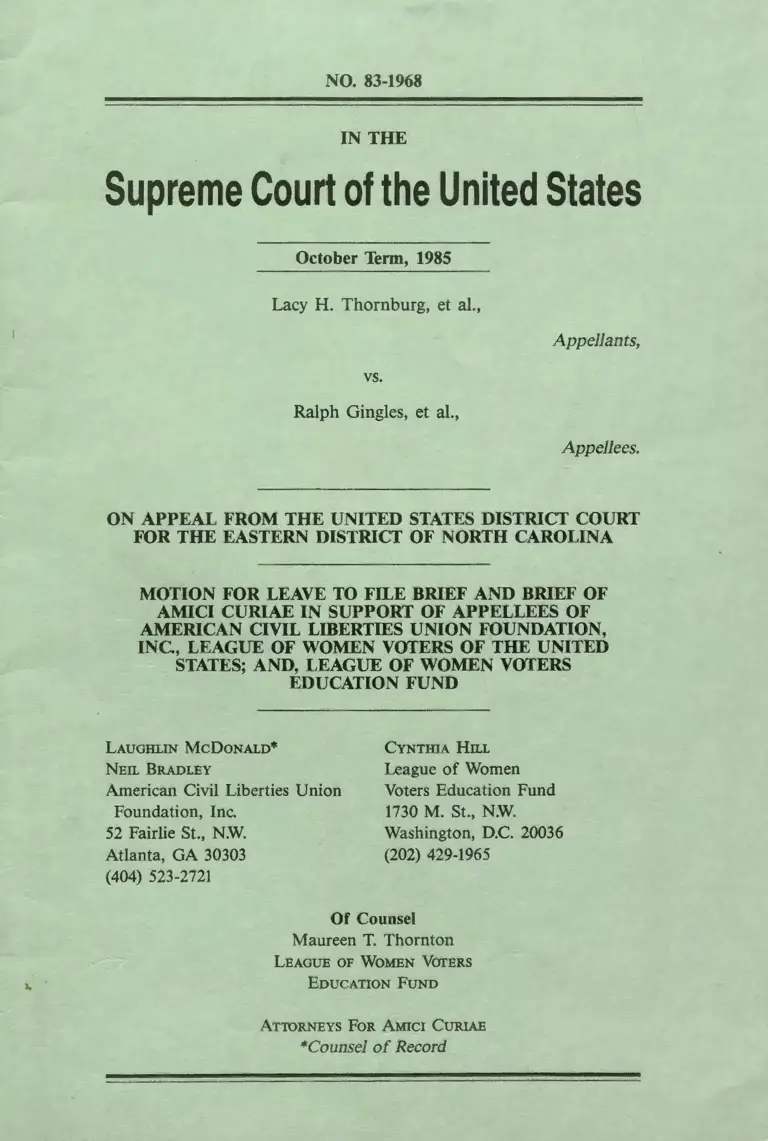

NO. 83-1968

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1985

Lacy H. Thornburg, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

Ralph Gingles, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AND BRIEF OF

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES OF

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION,

INC., LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS OF THE UNITED

STATES; AND, LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS

EDUCATION FUND

LAUGHLIN McDoNALD*

NEIL BRADLEY

CYNTHIA HILL

League of Women

Voters Education Fund

1730 M. St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 429-1965

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

52 Fairlie St., N.W.

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

Of Counsel

Maureen T. Thornton

LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS

EDUCATION FUND

ATTORNEYs FoR AMICI CuRIAE

*Counsel of Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities .••• • .••••••.. iii

Motion for Leave to File Brief

of Amici Curiae .. ................. x

Interests of Amici Curiae ••••••... l

Statement of the Case ••••••.••••.. 2

Summary of Argument .•.••••.•....•. 2

Argument . ............... . ......... 5

I. The Election of a Token Number

of Minority Candiates Does Not

Foreclose a Section 2

Challenge.

A. The Statute and the

Legislative History ..•.••• S

B. Congressional Policy Favors

Strong Enforcement of Civil

Rights Laws •.••••.•..•.•.. 30

II. The District Court Properly

Found Racial Bloc Voting.

A. The Court Applied Correct

Standards ........•••••.•.•• 36

• B. The Court's Methodolgy

Was Acceptable ••..•..•••••• 42

-i-

C. This Court Should Not Adopt

A Rigid Definition or Method

of Proof of Bloc Voting ..•. 52

Conclusion .......................... 65

Appendix A .......................... A-1

-ii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pase(s)

Alexander v. Louisiana,

405 u.s. 625 (1972) ••.•••.•.••.. 55,56,57

Allain v. Brooks,

No. 83-2053 .... ................. 48

Berry v. Cooper,

577 F.2d 322

(5th Cir. 1978) .•.•••.••••.•••.• 55

Bolden v. City of Mobile

423 F. Supp. 384

(S.D. Ala. 1976) .••••...••...••• 44

Castaneda v. Partida,

430 u.s. 482 (1977) ..••••.••••.• 55,57

City of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55 (1980) ..•.••••.•..• passim

City of Rome, Georgia v.

United States,

472 F. Supp. ,221 (D.C. 1979) ••••. 62

City of Rome v. United States,

446 u.s. 156 (1980) •••.•••.•••..• 62

City of St. Petersburg v.

United States, 354 F. Supp.

1021, (D.D.C 1972) ••.••••••••••.. 44

Cross v. Baxter,

604 F.2d 875

(5th Cir. 1979) •.•••.•..•.•..••• 25,60,61

-iii-

Cases, cont'd.

Foster v. Sparks,

506 F.2d 805, 811-37

Page(s)

( 5th c i r . l 9 7 5 ) ••••.......••.•. 54

Garcia v. United States,

u.s. I lOS s. Ct. 479

.,.,..( -=-1 =-9 8=-4 > . . . . . . . . . . . . . . • • . . • • . . . . . 2 1

Gingles v. Edmisten,

59 0 F • s u pp . I 3 4 5 ( E • D . N . c . 28,38

1984) .......................... 39,42

Hunter v. Underwood,

u.s. I lOS s. Ct. 1916

....,.(~1~98=-s· ) •. -.•.•..••....•..•..•...•• xi

Jones v. City of Lubbock,

730 F.2d 233, 727 F.2d 364 xiii,45

(5th Cir. 1984) •.•...••••••••.•. 47,48,49

Jordan v. Winter,

Civ. No. GC-80-WK-0

(N.D. Miss. April 16, 1984) ...••. 47

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors,

554 F.2d 139

(5th Cir. 1977) •.......•.•••••.••• 25

Lodge v. Buxton,

Civ. No. 176-55

(S.D. Ga. Oct. 26, 1978) ..•..•.... 43

Major v. Treen,

574 F. Supp. 325

(E. D. La. 198 3) .•.............•.•. 2 6

Mandel v. Bradley,

432 u.s. 173 (1977) •••.....••....• 49

-iv-

Cases Page{s)

McCain v. Lybrand,

u.s. , 104 s.ct. 1037

-..( -=-1..,...9 8-=-4 > • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • x i i

McMillan v. Escambia County,

748 F.2d 1037

{5th Cir. 1984) ••.•.• . .. • .•.•••.••. 45

Mississippi Republican Executive

Committee v. Brooks, U.S. ,

105 S.Ct. 416 {1984) .••••••...••. 48,49

NAACP v. Gadsden County School Board,

691 F.2d 978

{11th Cir. 1982) .•.....•••..••.•...•• 45

Nevett v. Sides,

571 F.2d 209 {5th Cir. 1978) ....••.•• 45

Rogers v. Lodge, xii

458 u.s. 613 {1982) .....••.....•..••. 44

Rybicki v. St~te Board of Elections,

574 F. Supp. 1147

{E.D. Ill. 1983) ...•.•.....••.•.•..•.. 26

Stephens v. Cox,

449 F.2d 657 {4th Cir. 1971) ••••••.. • • 55

South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 u.s. 301 {1966) ......•....••.•...• 30

Swain v. Alabama,

380 u.s. 202 {1965) .•••..•.•...•.. 53,54

United States v.

Dallas County Commission,

739 F.2d 1529 {11th Cir. 1984) •.••. 51

-v-

Cases, cont'd Page(s)

United States v. Jenkins,

496 F.2d 57 (2d Cir. 1974) .••.•.... 34

Unites States v.

Marengo County Commission,

731 F.2d (11th Cir. 25,

1984) • • • • • • • .· • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 43 1 45

Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

725 F.2d 1017

(5th Cir. 1984) •...•••..•....•..••.• 26

White v. Regester, 412 U.S . 755

( 19 7 3 ) .......•.................... passim

Zimmer v. McKeithen,

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) ..... passim

Zuber v. Allen,

396 u.s. 168 (1969) ..•....•...•.•...•. 21

Constitutional Provisions:

Fifteenth Amendment • .••.•.......... ll

Statutes

28 u.s.c. §1861 ..•....••..•••.••.•.• 33

42 u.s.c . §1973 •..•••••••••• . ... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000a •• .• .. . •. • . • •. • . . • • • 32

42 u.s.c . §2000e ••...•.• • .•.•.•.••. • 33

-vi-

Statutes, cont'd Page(s)

84 Stat. 314 •..•.•••.•.•• • •..•...... 31

89 Stat. 402 ....................... . 31

96 Stat. 131 ........................ 31

96 Stat. 134 ........................ 10

Federal Jury Selection and Service 33

Act of 1968 .....••..•••.•••.••.•• 34,35

Section 2,

Voting Rights Act of 1965 ••.••.. passim

Section 5,

Voting Rights Act of 1965 .........•.. 31

Title II,

C i vi 1 Rights Act of 19 6 5 ••• ·. . . • . . . 3 2 , 3 4

Title VII,

Civil Rights Act of 1964 .•..•..••. 33,34

Voting Rights Act of 1965 ..•.•..•...• 30

Other Authorities

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD

127 Cong. Rec. H7011 .................. 11

(

128 Cong. Rec. H3839 . ................. 16

128 Cong. Rec. 86930 ... ............... 24

128 Cong. Rec. 86956 .. ............... . 16

-vii-

Other Authorities, cont'd Page(s)

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD

128 Cong. Rec. S6965 .••••.•••••.•.•••• 16

128 Cong. Rec. S7139 ••••••••...•...•.• 16

Congressional Hearings

Voting Rights Act:

Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution of the

Senate Comm. of the Judiciary,

Vol. 1, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.,

(1982) ......................... 14,24

Congressional Reports

H.R. Rep. No. 914 , 88th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1963) ..•.•.•.•• 32,33

H.R. Rep. No. 1076, 90th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1968) •••••••.••••. 33

House Rep. No. 97-227, 97th Cong.,

lst Sess. (1981) .•• ••.•• ..• •. 13,19,20

Senate Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1982) ...•••.•..••.•.• passim

Voting Rights Act: Report of the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of

the Senate Comm. on the Judiciary,

97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) •••••••.• 13

-viii-

House and Senate Bills Page(s)

H.R. 3112. .11,16

s. 1992 ••. • ••• 16

-ix-

No. 83-1968

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

RALPH GINGLES, ET AL.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES OF

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

FOUNDATION, INC.; LEAGUE OF WOMEN

VOTERS OF THE UNITED STATES; AND,

LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS EDUCATION FUND

Come now the above listed

organizations, by counsel, and move the

Court for leave to file a brief amici

curiae in support of the Appellees in

-x-

the above styled cause. 1

The American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc. (ACLU) is a non-profit,

nationwide, membership organization

whose purpose is the defense of the

fundamental rights of the people of the

United States. A particular concern of

the ACLU is the enforcement of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, and

implementing legislation enacted by

Congress, in the area of minority voting

rights. Attorneys associated with the

ACLU have been involved in numerous

voting rights cases on behalf of racial

minorities, including, most recently in

this Court, Hunter v. Underwood,

u.s. ---

1counsel for

given consent

brief.

105 S. Ct. 1916 (1985);

the

to

Appellants

the filing

-xi-

have

of

not

this

McCain v. Lybrand, U.S. , 104

S. Ct. 1037 (1984); and Rogers v. Lodge,

458 u.s. 613 (1982).

The League of Women Voters of the

United States (LWVUS, or League) is a

national, nonpartisan, nonprofit

membership organization with 110,000

members in all 50 states, the District

of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Virgin

Islands. The LWVUS's purpose is to

promote political responsibility through

informed and active participation of

citizens in government. The LWVUS

believes voting is a fundamental right

that must be fostered and protected.

With its network , the LWVUS was a major

participant in the effort to strengthen

and extend the Voting Rights Act in

1982. Leagues and the LWVUS have been

active in voting rights litigation.

The League of Women Voters

-xii-

Education Fund (LWVEF), an affiliate of

the LWVUS, is a nonpartisan, nonprofit

education organization, one of whose

purposes is to increase public

understanding of major public policy

issues. The LWVEF provides a variety of

services, including research,

publications, monitoring and litigation

on current issues, such as voting rights

and election administration. The

LWVEF's docket includes Jones v. City of

Lubbock, 730 F.2d 233, 727 F.2d 364 (5th

Cir. 1984), in which a local League

member was a named plaintiff.

This case presents important issues

involving the application of Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. § 1973, and whether the statute

protects equal, or as argued by

Appellants and the United States, merely

token minority access to the political

-xiii-:

process. Because of the experience of

amici in advocating minority voting

rights, and because the parties may not

adequately present the Section 2 issues

discussed in this brief, amici believe

their views may be of some benefit to

the Court in resolving the issues raised

in this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

. * Laughl~n McDonald

Neil Bradley

American Civil

Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

52 Fairlie St.,N.W.

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

Of Counsel:

Maureen T. Thornton

League of Women Voters

Education Fund

Cynthia D. Hill

League of Women

Voters Education

Fund

1730 M. St., N.W.

Washington, D.C.

20036

(202) 429-1965

Attorneys For Amici Curiae

* Counsel of Record

-xiv-

No. 83-1968

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

LACY H. THORNBURG, ET AL.,

Appellants,

versus

RALPH GINGLES, ET AL.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF

APPELLEES OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES

UNION FOUNDATION, INC.; LEAGUE OF WOMEN

VOTERS OF THE UNITED STATES; AND,

LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS EDUCATION FUND

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The interests of amici curiae are

set forth in the motion for leave to

file this brief, supra, p. x.

-1-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Amici adopt the statement of the

case contained in the Brief of

Appellees.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In 1982 Congress amended Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §

1973, to make clear its purpose of

prohibiting voting procedures that

result in discrimination. The

construction urged upon this Court by

the Appellants and the Solicitor General

that the elect ion of a token number

of minorities to office in the disputed

districts of North Carolina's 1982

legislative reapportionment forecloses a

challenge under Section 2 -- is totally

inconsistent with Congress's purposes in

-2-

amending Section 2.

The language and the legislative

history of Section 2 expressly show that

there is no validity to the argument

that minimal success by minority

candidates can be equated with fair and

effective participation of minorities in

the political process. Section 2 is

designed to protect the right to equal,

not token or minimal, participation.

The extent to which minorities have been

elected is only one of the factors to be

considered ,by a court in evaluating a

Section 2 claim.

Congress has articulated a policy

that favors strong enforcement of civil

rights. Such a policy clearly does not

embrace

voting.

Solicitor

tokenism or minimal ism in

If the Appellants and the

General prevail in their

argument, there will be no incentive for

-3-

jurisdictions to comply voluntarily with

the Voting Rights Act, but instead they

will be encouraged to resist and to

circumvent Section 2.

The district court applied correct

legal standards and methods of analysis

in finding racial bloc voting. The

imposition of any rigid definitions or

methodologies for proving bloc voting

would be inconsistent with the purposes

of Section 2, would unduly burden

minority plaintiffs and in some cases

would make it impossible to challenge

discriminatory voting practices.

The judgment below should be

affirmed on the grounds that the trial

court properly applied Section 2.

-4-

ARGUMENT

I. THE ELECTION OF A TOKEN NUMBER OF

MINORITY CANDIDATES DOES NOT

FORECLOSE A SECTION 2 CHALLENGE.

A. The Statute and the

Legislative Hist~

Both the Appellants and the

Solicitor General, as counsel for amicus

curiae the United States, argue that the

election of a token number of minorities

to office in the disputed districts of

North Carolina's 1982 legislative

reapportionment absolutely forecloses

Appellees' challenge to the . diluting

effect of at-large voting and multi-

member districting under Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973. See Appellants' Brief, p. 24:

"The degree of success at the polls

-5-

enjoyed by black North Carolinians is

sufficient in itself to distinguish this

case from White [v. Resester ,412 u.s.

755 (1973] and Mobile [v. Bolden, 446

u.s. . 55 (1980) ] and to entirely

discredit the plaintiffs' theory that

the present legislative districts deny

blacks equal access to the political

process." (emphasis supplied); Brief for

the United States as Amicus Curiae, p.

27: "multimember districts are not

unlawful where, as here, minority

candidates are not effectively shut out

of the electoral process." 1

1The Solicitor General, underscoring the

extremity of this position, noted that

" [ t]he closest analogy to this case is

Dove v. Moore, supra, in which the court

of appeals upheld the validity of an at

large system under which the 40% black

minority elected one member to an eight

member city council." (emphasis

supplied). Id., at 27-8.

-6-

The argument that minimal success

by minority candidates absolutely

forecloses a Section 2 challenge is

refuted by the language of the statute

itself. 2 First, the statute requires

2section 2 provides in full:

(a) No voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or

political subdivision in a manner

which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any

citizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color,

or ip contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section

1973b(f)(2) of this title, as

provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a}

of this section is established if,

based on the totality of

circumstances, it is shown that the

political processes leading to

nomination or election in the State

or political subdivision are not

equally open to participation by

members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a} of this

section in that its members have

less opportunity than other members

[Footnote continued]

-7-

that political processes be "equally

open" to minorities, and that they not

have "less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate

in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice." The

right protected by the statute,

therefore, is one of equal, not token or

minimal, political participation.

Second, the statute directs the

trial court to consider "the totality of

circumstances" in evaluating a

violation, and provides that "[t]he

of the electorate to participate in

the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice.

The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected

to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided,

that nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in

numbers equal to their proportion

in the population.

-8-

extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered."

Obviously, if black electoral success is

merely one of the "totality" of

circumstances which may be considered by

a court in evaluating a Section 2 claim,

a finding of minimal or any other level

of success could not be dispositive.

The statute on its face contemplates

that other circumstances may and should

be considered.

The legislative history of Section

2 makes the point explicitly. It

provides that factors in addition to the

election of minorities to office should

be considered, and that minority

candidate success does not foreclose the

possibility of dilution of the minority

vote. See Senate Rep. No. 97-417, 97th

-9-

Cong., 2d Sess. 29 n.llS (1982)

(hereinafter "Senate Rep.").

In 1982, Congress amended Section 2

to provide that any voting law or

practice is unlawful if it "results" in

discrimination on acount of race, color

or membership in a language minority.

96 Stat. at 134, §3, amending 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973. Prior to amendment, the statute

provided simply that no voting law or

practice "shall be imposed or

applied ... to deny or abridge the

right .•. to vote on account of race or

color" or membership in a language

minority. 3 A plurality of this Court,

3The statute provided in its entirety:

"No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting, or standard, practice or

procedure shall be imposed or applied by

any State or political subdivision to

deny or abridge the right of any citizen

of the United States to vote on account

of race or color, or in contravention of

the guarantees set forth in Section

[Footnote continued]

-10-

however, in City of Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55, 60-1 (1980), held that "the

language of §2 no more than elaborates

upon that of the Fifteenth Amendment,"

which it found to require purposeful

discrimination for a violation, and that

"the sparse legislative history of §2

makes clear that it was intended to have

an effect no different from that of the

Fifteenth Amendment itself."

Congress responded directly to City

of Mobile by amending the Voting Rights

Act. The House, by a vote of 389 to 24,

passed an amendment to Section 2 on

October 5, 1981. 127 Cong. Rec. H7011

(daily ed., Oct. 5, 1981). The House

bill, H.R. 3112, provided (the language

in brackets was deleted and the language

in italics was added):

1973b(f)(2) of this Title."

-11-

Section 2. No voting

qualification or prerequisite to

voting, or standard, practice, or

procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political

subdivision [to deny o~ abridge] in

a manner which results in a denial

or abridsement of the right of any

c1tizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color,

or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section

4(f)(2). The fact that members of

a minoritl 9roup have not been

elected in numbers equal to the

3!0UE 1 s Eroportion of the

EOEulation shall not, 1n a~ of

itself, constitute a violation of

t'hrs section.

As the Report of the House Committee on

the Judiciary explained, the purpose of

the amendment was "to make clear that

proof of discriminatory purpose or

intent is not required in cases brought

under that provision," and "to restate

Congress' earlier intent that violations

of the Voting Rights Act, including

Section 2, could be established by

showing the discriminatory effect of the

-12-

challenged practice." House

97-227, 97th Cong., lst Sess.

{hereinafter "House Rep.").

Rep. No.

29 {1981)

In the Senate, the Subcommittee on

the Constitution, chaired by Senator

Orrin Hatch, rejected the Section 2

amendment and reported out a ten year

extension of Section 5 and the other

temporary provisions of the Act by a

vote of 3 to 2. Voting Rights Act:

Report of the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the Senate Comm. on the

Judiciary, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 67

{1982). The Senate Judiciary Committee,

however, pursuant to the so-called "Dole

Compromise," authored by Sen. Robert

Dole, returned the results standard to

Section 2 and added subsection {b),

taking language directly from White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 766 {1973). The

purpose of the addition was to clarify

-13-

that the amended statute "is meant to

restore the pre-Mobile legal standard

which governed cases challenging

election systems or practices as an

illegal dilution of the minority vote,"

and "embodies the test laid down by the

Supreme Court in White." Senate Rep. at

27. The Senate bill also provided, as

did the House bill, that amended

Section 2 did not guarantee the right to

proportional representation.

30-1.

Id. , at

The Senate disclaimer was designed

to meet criticism, particularly by

Senator Hatch, that the language of the

House bill would permit a violation of

the statute merely upon a showing of

lack of a proportional number of

minorities in office and "an additional

scintilla of evidence." Voting Rights

Act: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on the

-14-

Constitution of the Senate Comm. of the

Judiciary, Vo~, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

516 (1982) (hereinafter "Senate

Hearings"). The compromise language was

intended to clarify (if indeed

clarification was needed) that a court

was obligated to look at the totality of

relevant circumstances and that, as in

"this White line of cases," minority

office holding was "one circumstance

which may be considered." 2 Senate

Hearings at 60 (remarks by Senator

Dole) . The compromise language,

however, was not intended to alter in

any way the House bill's totality of

circumstances formulation based upon

White. That is made clear by the Senate

Report which provides that the

Committee's substitute language was

"faithful to the basic intent of the

Section 2 amendment adopted by the

-15-

House," and was designed simply "to

spell out more specifically in the

statute the standard that the proposed

amendment is intended to codify . "

Senate Rep. at 27.

The Senate passed the Senate

Judiciary Committee's Section 2 bill

without change on June 18, 1982. 128

Cong. Rec. S7139 (daily ed., June 18,

1982). 4 The Senate bill (S. 1992) was

returned to the House where it was

incorporated into the House bill (H.R.

3112) as a substitute, and was passed

unanimously. 128 Cong. Rec. H3a39-46

(daily ed., June 23, 1982).

Both the House and Senate Reports

4Prior to passage the Senate defeated by

a vote of 81 to 16 a proposed amendment

deleting the "results" language from the

bill introduced by Senator John East.

128 Cong. Rec. S6956, S6965 (daily ed.,

June 17, 1982).

-16-

give detailed guidelines on the

implementation of Section 2 and

congressional intent in amending the

statute. According to the Senate

Report, plaintiffs can establish a

violation by showing "a variety of

factors [taken from White, Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en bane), aff 'd on other grounds sub.

nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), and other

pre-Bolden voting cases], depending upon

the kind of rule, practice, or procedure

called into question." Senate Rep. at

28. Typical factors include:

1. the extent of any history of

official discrimination in the

state or political subdivision that

touched the right of the members of

the minority group to register, to

vote, or otherwise to participate

in the democratic process:

2. the extent to which voting in

the elections of the state or

political subdivision is racially

polarized:

-17-

3. the extent to which the state

or political subdivision has used

unusually large election districts,

majority vote requirements, anti

single shot provisions, or other

voting practices or procedures that

may enhance the opportunity for

discrimination against the minority

group;

4. if there is a candidate

slating process, whether the

members of the minority group have

been denied access to that process;

5. the extent to which members of

the minority group in the state or

political subdivision bear the

effects of discrimination in such

areas as education, employment and

health, which hinder their ability

to participate effectively in the

political process;

6. whether political campaigns

have been characterized by overt or

subtle racial appeals;

7. the extent to which members of

the minority group have been

elected to public office in the

jurisdiction.

Id., at 28-9.

The factors set out in the Senate

Report were not deemed to be exclusive,

but illustrative: "while these

-18-

enumerated factors will often be the

most relevant ones, in some cases other

factors will be indicative of the

alleged dilution." Id. In addition,

Congress made it plain that "there is no

requirement that any particular number

of factors be proved, or that a majority

of them point one way or the other."

Id. Instead, Section 2 "requires the

court • s overall judgment based on the

totality of circumstances and guided by

those relevant factors in the particular

case, of whether the voting strength of

minority voters is ••• 'minimized or

cancelled out."' Id., at 29 n.ll8.

The House Report is to the same

effect: "the court should look to the

context of the challenged standard,

practice or procedure," and consider

"[a]n aggregate of objective factors"

taken from pre-Mobile decisions, similar

-19-

to those set out in the Senate Report.

House Rep. at 30. And like the Senate

Report, the House Report provides that

"[a]ll of these factors need not be

proved to establish a Section 2

violation." Id.

Not only does the legislative

history provide that no one factor is

dispositive in vote dilution cases, and

that the courts should consider the

totality of relevant circumstances, but

the argument of the State and the

Solicitor General that minimal or token

minority candidate success forecloses a

statutory challenge was considered and

expressly rejected. While the extent to

which minorities have been elected to

office is a significant and relevant

factor in vote dilution cases, the

Senate Report indicates that it is not

conclusive.

-20-

The fact that no members of a

minority group have been elected to

office over an extended period of

time is probative. However, the

election of a few minority

candidates does not 'necessarily

foreclose the possibility of

dilution of the black vote', in

violation of this section. Zimmer

485 F. 2d at 1307 . If it did, the

possibility exists that the

majority citizens might evade the

section e.g., by manipulating the

election of a 'safe' minority

candidate. 'Were we to hold that a

minority candidate's success at the

polls is conclusive proof of a

minority group's access to the

political process, we would merely

be inviting attempts to circumvent

the Constitution •.. Instead we shall

continue to require an independent

consideration of the record.'

Ibid.

Id., at 29 n.ll55

5The Solicitor General attempts to

discount the Senate Report on this point

by arguing that the report "cannot be

taken as determinative on all counts."

Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae, p. 24 n.49. Of course, this

Court has "repeatedly stated that the

authoritative source for finding the

legislature's intent lies in the

Committee reports on the bill." Zuber

v. Allen, 396 U.S. 168, 186 (1969).

Accord, Garcia v. United States,

[Footnote continued]

-21-

In Zimmer, relied upon in the

Senate Report, three black candidates

won at-large elections in East Carroll

Parish after the case was tried. The

county argued, as the State and

Solicitor General do here, that these

successes "dictated a finding that the

at-large scheme did not in fact dilute

the black vote." 485 F.2d at 1307. The

Fifth Circuit disagreed:

we cannot endorse the view that the

success of black candidates at the

polls necessarily forecloses the

possibility of dilution of the

black vote. Such success might, on

occasion, be attributable to the

u.s. 105 s. Ct. 4 79 I 483

(1984). In any case, there is simply

nothing in the legislative history to

indicate that there was any disagreement

with the proposition that "the election

of a few minority candidates does not

'necessarily foreclose the possibility

of dilution of the black vote', in

violation of this Section." Senate Rep.

at 29, n. 115.

-22-

work of politicians, who,

apprehending that the support of a

black candidate would be

politically expedient, campaign to

insure his election. Or such

success might be attributable to

political support motivated by

different considerations namely

that election of a black candidate

will thwart successful challenges

to electoral schemes on dilution

grounds. In either situation, a

candidate could be elected despite

the relative political backwardness

of black residents in the electoral

district.

Id.

Similarly, in White v. Regester,

the case principally relied upon by

Congress as embodying the 11 results 11

standard it incorporated into Section 2,

and whose language Congress expressly

adopted, two blacks and five Mexican-

Americans had been elected to the Texas

Legislature from Dallas and Bexar

Counties. 412 u.s. at 766, 768-69.

Despite that level of minority candidate

success, which is greater than that in

-23-

some of the districts claimed by the

State and the Solicitor General to be

immune from a Section 2 ' challenge here,

e.g. House Districts 8 and 36, and

Senate Districts 2 and 22, this Court in

a unanimous decision held at-large

elections impermissibly diluted minority

voting strength in those counties.

In addition to White and Zimmer,

the Congress, in amending Section 2,

relied upon some 23 courts of appeals

decisions which had applied a results or

effect test prior to City of Mobile.

Senate Rep. at 32, 194; 128 Cong. Rec.

S6930 (daily ed. June 17, 1982) (remarks

of Sen. DeConcini): 6 One of those 23

6The 23 cases are listed and discussed

in 1 Senate Hearings at 1216-26

(appendix to prepared statement of Frank

R. Parker, Director, Voting Rights

Project, Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law).

-24-

cases, Kirksey v. Board of SuEervisor~,

554 F.2d 139, 149 n.21 (5th Cir. 1977),

commented upon the continuing validity

of the Zimmer rule that the election of

a minimal number of blacks did not

foreclose a dilution claim: "we add the

caveat that the election of black

candidates does not automatically mean

that black voting strength is not

minimized or cancelled out." Accord,

Cross v. Baxter, 604 F.2d 875, 880 n.7,

885 (5th Cir. 1979).

Cases decided since the amendment

of Section 2 have predictably applied

the statute in light of the legislative

history and rejected the contention that

minimal or token black success at the

polls forecloses a dilution claim. See,

United States v. Marengo County

Commission, 731 F.2d 1546, 1571-72 (11th

Cir. 1984) ("it is equally clear that

-25-

the election of one or a small number of

minority elected officials will not

compel a finding of no dilution"), cert.

denied, u.s. I 105 s. Ct. 375 ---

(1984); Velasquez v. City of Abilene,

725 F.2d 1017, 1023 (5th Cir. 1984) ("In

the Senate Report •.. it was specifically

noted that the mere election of a few

minority candidates was not sufficient

to bar a finding of voting dilution

under the results test."); Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325, 339 (E.D. La.

198 3) ; . Rybicki v. _s_t_a_t_e __ B_o_a_r_d~_o_f

Elections, 574 F. Supp. 1147,

n. 5 (E. D. I 11 . ( 198 3 ) .

1151 and

The necessity of considering

factors other than the election of

minorities

apparent in

County) and

to office is particularly

House District 21 (Wake

House District 23 (Durham

County), districts in which blacks,

-26-

according to the Solicitor General, have

enjoyed "proportional representation."

Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae Supporting Appellants, p.25.

While one black has been elected to the

three member delegation from House

District 23 since 1973, and a black has

been elected in 1980 and 1982 to the six

member delegation

21, the district

from House District

court found this

success was the result of single shot

voting by blacks, a process which

requires minorities to give up the right

to vote for a full slate of

candidates. According to the lower

court, "[o]ne revealed consequence of

this disadvantage [of a significant

segment of the white voters not voting

for any black candidate] is that to have

a chance of success in electing

candidates of their . choice in these

-27-

districts, black voters must rely

extensively on single-shot voting,

thereby forfeiting by practical

necessity their right to vote for a full

slate of candidates." Gingles, · 590 F.

Supp. at 369. Under the circumstances,

the election of blacks in these

districts can not mask the fact that the

multi-member

unfairly and

strength.

system treats minorities

dilutes their voting

Black voters in House District 23

must forfeit up to two-thirds of their

voting strength and black voters in

House District 21 must forfeit up to

five-sixths of their voting strength to

elect a candidate of their choice to

office. Whites, by contrast, can vote

for a full slate of candidates without

forfeiting any of their voting strength

and elect candidates of their choice to

-28-

office. Such a s ystem clear ly does not

provide black vot ers equa l access nor

the equal opportunity to participate in

the political process and elect

candidates of their choice to office.

That is another reason why the mere

election of even a proportional number

of blacks to office does not, and should

not, foreclose a . dilution challenge. As

Section 2 and the legislative history

provide, a court must view the totality

of relevant circumstances to determine

whether the

minorities is

voting strength of

in fact minimized or

abridged in violation of the statute.

To summarize, the position of the

State and the Solicitor General that the

election of a token or any other number

of blacks to office bars a dilution

challenge must be rejected because it is

contrary to the express language of

-29-

Section 2, the legislative history and

the pre-Mobile line of cases whose

standards Congress incorporated into the

"results" test.

B. Congressional Policy Favors

~~ron9 Enforcement of Civil

R19hts Laws

Congress enacted the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 as an "uncommon exercise of

congressional power" designed to combat

the "unremitting and ingenious defiance

of the Constitution" by some

jurisdictions in denying minority voting

rights. South Carol ina v. Ka tzenbach,

383 u.s. 301, 309, 334 (1966). Based

upon the continuing need for voting

rights protection, Congress extended and

expanded the coverage of the Act three

-30-

times in 1970, 1975 and 1982. 7 It

would be illogical to suppose, that in

amending Section 2, Congress suddenly

retreated from its general commitment to

racial equality in voting and adopted a

statute providing only tokenism and

minimal political participation. That

is certainly not what the Congress

thought it was doing. As the Senate

Report provides, the purpose of the 1982

7voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970,

84 Stat. 314 (extending Section 5

coverage and the other special

provisions of the Act for five more

years; adding jurisdictions for special

coverage; establishing a five year

nationwide ban on literacy tests); Act

of August 6, 1975, 89 Stat. 402

(extending Section 5 and the other

special provisions for seven additional

years; making permanent the nationwide

ban on literacy tests; extending Section

5 to language minorities and requiring

bilingual registration and elections in

certain jurisdictions); Voting Rights

Act Amendments of 1982, 96 Stat. 131

(extending Section 5 for twenty-five

years and amending Section 2).

-31-

legislation was to "extend the essential

protections of the historic Voting

Rights Act ... [and] insure that the hard

won progress of the past is preserved

and that the effort to achieve full

participation for all Americans in our

democracy will continue in the

future." Senate Rep. at 4.

Modern congressional civil rights

enforcement policy in other areas has

similarly not been one of minimalism.

Congress, for example, clearly intended

to protect more than token access to

public accommodations when it enacted

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000a et. seq .. See,

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 2d Sess.

{1963), reprinted in [1964] 2 U.S. Code

Cong. & Ad. News 2393 {"It

is ••. necessary for the Congress to enact

legislation which prohibits and provides

-32:...

the means to

serious types

terminating the most

of discrimination.")

Congress also sought to protect more

than token access to employment

opportunities and jury service when it

enacted Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et. seq.,

and the Federal Jury Selection and

Service Act of 1968, 28 U.S.C. § 1861

et. ~· H.R. Rep. No. 914, supra, U.S.

Code Cong. & Ad. News at 2401 ("the

purpose of this title is to

eliminate ... discrimination in employment

based on race, color, religion, or

national origin."); H.R. Rep. No. 1076,

90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968), reprinted

~ [1968] 2 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

1793 (a major purpose of the Federal

Jury Act is to establish "an effective

bulwark against impermissible forms of

discrimination and arbitrariness in jury

-33-

selection . ")

II

2 does not guarantee

representation any more

guarantees proportional

Section

proportional

than Title

occupancy of places of public

accommodation, or Title VII guarantees

proportionality in hiring, or the

Federal Jury Act guarantees juries that

proportionately represent minorities.

See,~-, United States v. Jenkins, 496

F.2d 57, 65 (2d Cir. 1974) ("The Act was

not intended to require precise

proportional representation of minority

groups on grand or petit jury

panels.") But certainly Title II could

not be rationally construed to bar a

challenge to an otherwise discriminatory

public accommodations policy merely

because any given number of rooms were

let to blacks, nor could Title VI I be

construed to bar an otherwise valid

-34-

employment discrimination claim merely

because a token number of minorities had

been hired, nor could the Federal Jury

Act be deemed to bar a challenge to a

discriminatory jury selection system

merely because a few blacks were allowed

into the jury pool. Such a reading of

congressional civil rights laws would be

illogical and totally contrary to the

intent of Congress in legislating

against discrimination. Yet, that is

the untenable position of the State and

the Solicitor General in this case.

If the State and the Solicitor

General

will

prevail in their

be impossible

argument, it

to eradicate

discriminatory election

places where minority

had some success. In

procedures in

candidates have

addition, those

jurisdictions in which black candidates

have had no success will be encouraged,

-35-

as Congress found, to manipulate the

election of a "safe" or token minority

candidate to give the appearance of

racial fairness and thwart successful

dilution challenges to discriminatory

election schemes. As a result, there

will be no incentive for voluntary

compliance with Section 2, and every

inducement for circumvention and

continued litigation. Future progress

in minority voting rights will be dealt

a severe setback.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY FOUND

RACIAL BLOC VOTING.

A. The Court Applied Correct

Standards

The State and the Solicitor General

argue that the district court applied a

-36-

legally incorrect definition of bloc

voting which vitiates its conclusions

that the challenged districts dilute

minority voting strength. 8 According to

the State, the lower court applied the

test that "polarized voting occurs

whenever less than 50% of the white

voters cast a ballot for the black

candidate." Appellants' Brief, p. 36.

According to the Solicitor General, the

court adopted a definition that

polarized voting occurs "whenever 'the

results of the individual election would

have been different depending upon

whether it had been held among only the

white voters or the black voters in the

8The State concedes that Appellees'

calculations were basically accurate,

and that the methods of analysis used

"were standard in the literature." 590

F. Supp. at 368.

-37-

election.'" Brief for the United States

as Amicus Curiae, p. 29.

While it is true, as the trial

court noted, that in none of the

elections did a black candidate receive

a majority of white votes cast, 590 F.

Supp. at 368, and that in all but two of

the elections the results would have

been different depending upon whether

they had been held among only the white

or only the black voters, id., the court

did not base its finding of bloc voting

merely upon these facts. The district

court examined extensive statistical

evidence of 53 sets of election returns

involving black candidacies in all the

challenged districts, heard expert and

lay testimony and concluded that:

On the average, 81.7% of white

voters did not vote for any black

candidate in the primary

elections. In the general

elections, white voters almost

always ranked black candidates

-38-

The

either last or next to last in the

multi-candidate field except in

heavily Democratic areas~ in these

latter, white voters consistently

ranked black candidates last among

Democrats if not last or next to

last among all candidates. In

fact, approximately two-thirds of

white voters did not vote for black

candidates in general elections

even after the candidate had won

the Democratic primary and the only

choice was to vote for a Republican

or no one. Black incumbency

alleviated the general level of

polarization reveal-ed, but it did

not eliminate it. Some black

incumbents were reelected, but none

received a majority of white votes

even when the election was

essentially uncontested.

Id.

court also found that the

polarization was statistically

significant in every election in that

the probability of it occurring by

chance was less than one in 100,000.

Id. 9 Taking the opinion as a whole, it

9The court determined "statistical

significance" by examining the

[Footnote continued]

-39-

is clear that the district court did not

adopt or apply a narrow, simplistic or

legally incorrect definition of

polarized voting.10

The State also contends that racial

bloc voting in the challenged districts

is irrelevant where a black won an

election. Appellants' Brief, pp. 39-

40: "Racially polarized voting is

correlations between the race of voters

and candidates prepared by Appellees'

expert. While "correlations above an

absolute value of .5 are relatively rare

and correlations above .9 extremely

rare •.. [a]ll correlations found by Dr.

Grofman in the elections studied had

absolute values between .7 and .98, with

most above .9. This revealed

statistical significance at the .00001

level probability of chance as

explanation for the coincidence of

voter's and candidate's race less than

one in 100,000." 590 F. Supp. at 368

n.30.

10Both the State and the Solicitor

General have opinions about when bloc

voting is relevant, but neither, it

should be noted, attempted to define

racial bloc voting.

-40-

significant ... when the black candidate

does not receive enough white support to

win the election ... The mere presence of

different voting patterns in the white

and black electorate does not prove

anything one way or the other about vote

dilution." Given this analysis, 100%

voting along racial lines would be

irrelevant in a challenge to multi

member district elections if blacks were

able to single-shot a black into

office. Congress indicated in the

statute and the legislative history,

however, that the totality of relevant

circumstances should be considered. One

of the relevant circumstances,

regardless of other factors that may be

present, is bloc voting.

-41-

B. The Court's Methodols~

Was Acceptable

In finding racial bloc voting, the

court below relied upon two methods of

statistical analysis employed by

Appellees' expert: extreme case analysis

and bivariate ecological regression

analysis. 11 Both methods are "standard

in the literature," as the lower court

found, 590 F. Supp. at 367 n.29, and

both have been extensively used by the

courts in voting cases in establishing

the presence or absence of racial bloc

11Extreme case analysis compares the

race of voters and candidates in

racially homogeneous precincts.

Regression analysis uses data from all

precincts and corrects for the fact that

voters in homogeneous and non-

homogeneous precincts may vote

differently. 590 F. Supp. at 367 n.29.

-42-

voting. 12

In Lodge v. Buxton, Civ. No. 176-55

(S.D. Ga. Oct. 26, 1978), slip op. at 7-

8, the trial court found racial bloc

voting in Burke County, Georgia, based

upon simple extreme case analysis in two

elections in which blacks were

candidates, a third election in which a

white sympathetic to black political

12Not all cases finding vote dilution,

however, have made findings of bloc

voting. Neither White v. Regester,

supra, nor Zimmer v. McKeithen, supra,

the cases principally relied upon by

Congress in establishing the results

standard of Section 2, made specific

findings that voting was racially

polarized. The legislative history of

Section 2 makes bloc voting a relevant

factor but does not indicate that it is

a requirement for a violation. See,

e.g., United States v. Marengo County

Commission, 731 F.2d 1546, 1566 (11th

Cir. 1984), citing the Senate Report and

concluding that "[w]e therefore do not

hold that a dilution claim cannot be

made out in the absence of racially

polarized voting."

-43,-

interests was a candidate and a fourth

election in which a black had won a city

council seat in a district with a high

percentage of black voters. The court's

analysis and discussion of bloc voting

is set out in Appendix A to this

brief. This Court affirmed the finding

of bloc voting in Burke County and the

conclusion that the at-large elections

were unconstitutional. Rogers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613, 623 (1982) ("there was

also overwhelming evidence of bloc

voting along racial lines").

For other cases approving the use

of extreme case or regression analysis

to prove bloc voting, see City of

Petersburg v. United States, 354 F.

Supp. 1021, 1026 n.lO (D.D.C. 1972),

aff'd, 410 U.S. 962 (1973): Bolden v.

City of Mobile, 423 F. Supp. 384, 388-89

(S.D. Ala. 1976) ("Regression analysis

-44-

is a professionally accepted method of

analyzing data."), aff'd, 571 F.2d 238

{5th Cir. 1978), rev'd on other grounds,

446 U.S. 55 {1980); Nevett v. Sides, 571

F.2d 209, 223 n.l8 (5th Cir. 1978)

{"bloc voting may be demonstrated by

more direct means as well, such as

statistical analyses ,

Ci t y of Mobile");

e.g.

NAACP

Bolden v .

v. Gadsden

County School Board , 691 F . 2d 978, 982-3

{ l l th Cir . 1982) {finding "compelling"

evidence of racial bloc voting based

upon bivariate analysis); United States

v. Marengo County Commission,

1546, 1567 n.34 {llth Cir.

731 F. 2d

1984) i

McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F. 2d

1037, 1043 n.l2 {5th Cir. 1984)

{confirming the use of regression

analysis comparing race of voters and

candidates to prove bloc voting); Jones

v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364, 380-81

-45-

(5th Cir. 1984) (approving the use of

bivariate regression analysis).

The State contends, however, that

bivariate regression analysis is

"severely flawed" and that the presence

of racial bloc voting can only be

estalished by use of a multivariate

analysis that tests or regresses for

factors other than race, such as age,

religion, income, education, party

affiliation, campaign expenditures, or

"any other factor that could have

influenced the election." Appellants'

Brief, pp. 41-2. 1 3 The State relies

13The Solicitor General does not support

the Appellants on this point, but agrees

with the Appellees that " [ i ]n most vote

dilution cases, a plaintiff can

establish a prima facie case of racial

bloc voting by using a statistical

analysis of voting patterns that

compares the race of a candidate with

the race of the voters." Brief for the

United States as Amicus Curiae, p. 30

n.S7.

-46-

principally upon the concurring opinion

of Judge Higginbotham in Jones v. City

of Lubbock, 730 F.2d 233, 234 (5th Cir.

1984), denying rehearing to 727 F.2d 364

(5th Cir. 1984) , in which he says in

dicta that proof of a high correlation

between race of voters and candidates

may not prove bloc voting in every case

and that it "will often be essential" to

eliminate all other variables that might

explain voting behavior.

Not only has this Court expressly

approved findings of bloc voting based

upon extreme

analysis, but

contention

case and regression

it has rejected the

that multivariate

regressional analysis is required. In

Jordan v. Winter, Ci v. No. GC-80-WK-0

(N.D. Miss. April 16, 1984), slip op. at

11, the three judge court invalidated

-47-

under Section 2 the structure of

Mississippi's second congressional

district in part upon a finding of a

"high degree of racially polarized

voting" based upon a bivariate

regression analysis comparing the race

of candidates and voters in the 1982

elections. The State appealed, Allain

v. Brooks, No. 83-2053, and challenged

the finding of bloc voting, citing Judge

Higginbotham's concurring opinion in

Lubbock ( id., Jurisdictional Statement

at 12- 3). 14

14see also, Justice Stevens concurring

op1nion in Mississippi Republican

Executive Committee v. Brooks,

U.S. , 105 S. Ct. 416 n.l (1985), --:-..-noting that the Jurisdictional Statement

in No. 83-2053 "presents the question

whether the District Court erroneously

found •.• that there has been racially

polarized voting in Mississippi."

-48-

The use of a regression analysis

which correlates only racial make

up of the precinct with race of the

candidate 'ignores the reality that

race ••. may mask a host of other

explanatory variables.' [730 F.2d]

at 235.

This Court summarily affirmed, sub nom.

Mississippi Republican Executive

Committee v. Brooks, u.s. 105 ------ ----~

S.Ct. 416 (1984), thereby rejecting the

specific challenge to the sufficiency of

bivariate regression analysis to prove

racial bloc voting contained in the

jurisdictional statement. Mandel v.

Bradle~, 432 U.S. 173, 176 (1977).

It should be reemphasized that

Judge Higginbotham ruled for the

plaintiffs in Lubbock and concurred in

the judgment affirming the dilution

finding by the district court. He

concluded that the defendants, other

-49-

than criticizing the plaintiffs'

methodology, failed to offer any

statistical evidence of their own in

rebuttal, and that accordingly

plaintiffs must be deemed to have

established bloc voting:

given that there is no evidence to

rebut plaintiffs' proof other than

the city's criticism of Dr.

Brischetto's study and its attempt

to show responsiveness, I agree

with Judge Randall that the record

is not so barren as to render

clearly erroneous the finding by

the district court that bloc voting

was established.

730 F.2d at 236.

Thus, the most that can be argued from

Judge Higginbotham's concurrence is that

where plaintiffs prove bloc voting by

correlation analysis, the proof must

stand unless defendants rebut

plaintiffs' evidence with statistics of

their own. The State made no such

rebuttal here.

-50-

In United States v. Dallas County

Commission, 739 F.2d 1529 (11th Cir.

1984}, the district court found evidence

of bloc voting based upon the

correlation of race of candidates with

voting, 739 F.2d at 1535 n.4, but

discounted it because of supposedly non

racial factors, e.g. voter apathy, the

advantage of incumbency, blacks ran as

"fringe party" candidates, etc. 739

F.2d at 1536. The court of appeals

rejected these non-racial explanations

for the defeat of black candidates

because of lack of support in the

record. Id. Th_e case thus approves the

proposition that it is sufficient to

establish racial bloc voting by

bivariate analysis, and if such a

finding is to be discounted, there must

be contradicting evidence in the

record. The State produced no

-51-

contradicting evidence in this case and

as a result its argument that bloc

voting was not proved should be

unavailing.

C. The Court Should Not Ado~

Rigid DefTnrtion or. ~d of

Proof of Bloc Voting

Aside from requiring polarization

to be significant, this Court should not

adopt any additional definition of

racial bloc voting. Section 2 analysis

requires a court to evaluate the

particular, unique facts of individual

cases. Imposing any rigid definition of

bloc voting in advance would thus be

inconsistent with the totality of

circumstances and individual appraisal

approach to dilution claims which

-52-

Congress has adopted. It might also

lead to findings of bloc voting or no

bloc voting in individual cases which,

in view of the totality of factors,

would be simply arbitrary.

This Court has avoided a single

formula approach to proof of

polarization or discrimination in other

areas of civil rights law. In jury

discrimination cases, for example, this

Court and lower federal courts have used

a number of tests for establishing a

prima facie showing of minority

exclusion but have never indicated that

one method of statistical analysis is

required in every instance.

In Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202

(1965), the Court indicated that a

disparity as great as 10% between blacks

in the population and blacks summoned

for jury duty would not prove a prima

-53-

facie case of unconstitutional

underrepresentation. Swain was

generally applied to mean that

disparities in excess of 10% would be

unconstitutional. Foster v. Sparks, 506

F.2d 805, 811-37 (5th Cir. 1975)

-

(Appendix to the Opinion of Judge

Gewin) . The so-called "absolute

deficiency" method of analysis used in

Swain does not give a true picture of

underrepresentation, however, when the

minority group is small. For example,

if the excluded group were 20% of the

population and 10% of those summoned for

jury duty, the absolute deficiency would

only be 10%, whereas in fact the group

would be underrepresented by one-half.

To meet the limitations of the

absolute deficiency standard, this Court

and lower federal courts have also used

a comparative deficiency test for

-54-

measuring underrepresentation, by which

the absolute disparity is divided by the

proportion of the population comprising

the specified category. Alexander v.

Louisiana, 405 U.S . 625, 629-30 (1972)

(using both the absolute and comparative

deficiency methods): Berr¥ v. Cooper,

577 F.2d 322, 326 n.ll (5th Cir. 1978):

Stephens v. Cox, 449 F.2d 657 (4th Cir.

1971). Those courts using the

comparative deficiency standard have

not, however, adopted any particular cut

off for racial exclusion.

This Court has also referred to,

without requiring that it be used, a

third method

underrepresentation

the statistical

of calculating

in jury selection,

significance test.

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 496

n.l7 (1977): Alexander v. Louisiana,

supra, 405 U.S. at 630 n.9, 632. The

-55-

test measures representativeness by

calculating the probability of a

disparity occurring by chance in a

random drawing from the population. The

district court in this case used this

method of analysis in part to support

its finding of bloc voting.

It is apparent from examining the

cases that this Court has not required a

single mathematical formula or standard

for measuring underrepresentation in all

jury selection cases and has, in fact,

expressly declined to do so. Alexander

v. Louisiana, supra, 405 U.S. at 630. A

similar approach to proof of bloc voting

in vote dilution cases would therefore

be consistent with this Court's

treatment of related discrimination

issues in other cases.

It is significant that none of the

tests for jury exclusion used by this

-56-

Court has required

disprove non-racial

_explanation for

underrepresentation.

challengers to

the factors as

minority

Instead, once a

prima facie case has been made using

some form of bivariate analysis, the

courts have held that the burden of

proving

racially

officials.

selection procedures are

neutral shifts to election

Alexander v. Louisiana,

supra, 405 U.S. at 632; Casteneda v.

Partida, supra, 430 U.S. at 497-98. In

the context of vote dilution litigation,

defendants might attempt to disprove

bloc voting by any method of analysis

they chose, including multivariate

regression analysis, but that should be

no part of plaintiffs' case.

It would be plainly inconsistent

with the intent of Congress to require

plaintiffs to conduct multivariate

-57-

analysis in Section 2 cases. In

amending Section 2 Congress adopted the

pre-Mobile dilution standards, and

bivariate correlation analysis was an

accepted method of proving bloc

voting. Therefore, this method of proof

should be satisfactory under Section 2.

Requiring plaintiffs to conduct

multivariate regression analysis would

also shift a court's inquiry from the

result or

lines to

fact

the

of voting

intent of

along racial

voters, an

inquiry which Congress intended to

pretermit

Congress

for three

in amending Section 2.

adopted the results standard

basic reasons.

Bolden intent test "asks

First, the

the wrong

97-417 at question." Senate Rep. No.

36. If minorities are denied a fair

opportunity to participate in politics,

existing procedures should be changed

-58-

regardless of the reasons the procedures

were established or are being

maintained. Second, the intent test is

"unnecessarily divisive" because it

requires plaintiffs to prove the

existence of racism. Id. Third, "the

intent test will be an inordinately

difficult burden for plaintiffs in most

cases." Id.

It would be tantamount to the

repeal of the 1982 law to say that proof

of intent is not required in Section 2

cases, and at the same time make

plaintiffs prove that voters were voting

purposefully for reasons of race to

establish a violation. Such an

evidentiary burden would again ask the

"wrong question," would be unnecessarily

divisive and would place inordinately

difficult

plaintiffs.

burdens on minority

It would essentially

-59-

nullify the intent of Congress in

enacting the statute.

There are a number of very

practical considerations, not discussed

by the State at all, which further

demonstrate the inherent unfairness, and

in some cases the impossibility, of

requiring minority plaintiffs to conduct

multivariate regression analysis.

( 1) Im,eossibili ty. In some cases

it will simply be impossible to do any

kind of regression analysis, or even an

extreme case analysis,~-~·' where there

is only one or no homogenious

precincts. Requiring a multivariate

regression analysis in a city with only

one polling place, such as Moultrie,

Georgia, see Cross v. Baxter, 604 F. 2d

875, 880 n.8 (5th Cir. 1979}, would

absolutely foreclose a dilution

challenge, even through minorities were

-60-

totally shut out of the political

and polarization was process

complete. 15 Such a result would be

absurd and contrary to the intent of

Congress in amending Section 2.

In still other cases, regression or

even extreme case analysis will be

-

impossible to perform because election

records no longer exist or cannot be

broken down into precincts. Such was

the situation in Rome, Georgia, where

the trial court nonetheless found bloc

voting and denied Section 5 preclearance

to a number of municipal voting

l5In Cross, the court of appeals held

simply that a finding by the trial court

of no bloc voting "on this record" would

be clearly erroneous where "[n]o black

candidate has ever received even a

plurality of white votes and Wilson, the

first black elected to the council

appears to have received as little as 5%

of white votes." Id.

-61-

changes.

United

CitX o f Rome, Georgia v.

States, 472 F. Supp. 221, 226

n.36 (D.C . 1979). This Court affirmed,

concluding that the district court did

not err in determining "that racial bloc

voting existed in Rome."

v. United States, 446

(1980).

City of Rome

u.s. 156, 183

( 2) Quantification. The State

ignores the enormous burden, and in some

instances the impossibility, of

quantifying, i.e. expressing in numbers,

all the non-racial factors potentially

influencing voters. It would be

difficult indeed to quantify candidate

expenditures or name recognition, or as

the State suggests, "any other factor

that could have influenced the

election," by precinct. Appellants'

Brief, pp. 41-2 . Perhaps these factors

could be quantified through extensive

-62-

surveys; perhaps not. But in any case,

the attempt to quantify them would be

enormously difficult, time consuming and

expensive and in most cases the burden

on minority plaintiffs would be

prohibitive.

The State's suggestion that

plaintiffs quantify and regress "any

other factor" that might have influenced

the elections would send plaintiffs on a

wild goose chase. Even if it were

possible,

literally ,

both financially and

for plaintiffs to provide a

multivariate analysis , defendants would

claim - as the State has here - that

allegedly relevant factors were omitted

and that the analysis thus must fail.

The State's argument is little more than

a prescription for maintenance of

discriminatory election practices.

{3) Unavailable Precinct Level

-63-

Data. The State fails to note that -

correlation analysis is almost always

based upon precinct level data. While

racial data is usually available,

precinct level data for income,

education, etc., generally does not

exist. The Census contains some of this

information by enumeration districts, or

in some states by block data, but not by

precincts. The cost and time involved

in extractng non-racial variables from

the Census at the precinct level, to the

extent that they are available at all,

would be overwhelming if not

prohibitive.

The State's contention that

Appellees must conduct a multivariate

analysis is contrary to Section 2, the

legislative history and the prior

decisions of this Court. The finding of

bloc voting and the methodology of the

-64-

lower court in this case were entirely

correct.

CONCLUSION

Amici Curiae respectfully urge the

Court to affirm the judgment below on

the grounds that the trial court

properly applied amended Section 2 to

find that North Carolina's 1982

legislative apportionment impermissibly

dilutes minority voting strength.

Respectfully submitted,

. * Laughl1n McDonald

Neil Bradley

American Civil

Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

52 Fairlie St.,N.W.

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

Of Counsel:

Maureen T. Thornton

Cynthia D. Hill

League of Women

Voters Education

Fund

1730 M. St., N.W.

Washington, D.C.

20036

(202) 429-1965

League of Women Voters, Education Fund

Attorneys For Amici Curiae

* Counsel of record

-65-

APPENDIX A

Trial Court's Analysis of Bloc Votinil_

in Lodge v. Buxton, Civ. No. 176-55

{S.D. Ga. Oct. 26, 1978), slip. op. at

7-9

There was a clear evidence of bloc

voting the only time Blacks ran for

County Commissioner. Obviously, this

must be ascribed in part to past

discrimination. There are three Militia

Districts in which Blacks are in a clear

majority, the 66th, 72d and 74th. 7

7The Court finds the following to

reasonably accurate estimate of

registered voters by race in

district, as of 1978.

Precinct Black White

Waynesboro

60-62 District 1,050 2,149

Munnerlyn

6lst District 44 50

[Footnote continued]

A-l

In a

be a

the

each

Total

3,199

94

fourth district, the 69th, as of 1978,

there were only a few more Blacks than

Whites. One black candidate, Mr.

Alexander

63rd District 75 104 179

Sardis

64th District 211 478 689

Keysville

65th District 163 214 377

Shell Bluff

66th District 167 82 249

Greenscutt

67th District 49 215 264

Girard

68th District 110 195 305

St. Clair

69th District 29 26 55

Vidette

7lst District 52 112 164

Gough

72d District 201 68 269

Midville

73rd District 184 195 379

Scotts Store

74th District 98 52 150

Total 2,433 3,940 6,373

A-2

Childers, won in the four black

districts, losing in all of the

others. The other black candidate, Mr.

Reynolds, won in three of the black

districts losing in all of the others. 8

Similarly, in 1970 Dr. John Palmer,

a white physician from Waynesboro, who

open the first integrated waiting room

in Burke County, ran for County

Commission.- Generally, he was thought

of as being sympathetic to black

political interests. He was soundly

defeated.

In the recent city council election

in Waynesboro, the county seat, a Black

was elected to the council for the first

time in history. This event can be

8 :Plaintiffs' Request for Admissions,

filed June 5, 1970, Exhibits I-3 and I-

4.

A-3

attributed to the high degree of bloc

voting, and to the fact that the elected

Black ran in a district with a high

percentage of black residents. 9

9This was possible because this Court

created single-member districts. See

Sullivan v. DeLoach, Civil No. 176-238

(S.D. Ga.) Order entered September 11,

1977.

A-4

NAACP0480

NAACP0481

NAACP0482

NAACP0483

NAACP0484

NAACP0485

NAACP0486

NAACP0487

NAACP0488

NAACP0489

NAACP0490

NAACP0491

NAACP0492

NAACP0493

NAACP0494

NAACP0495

NAACP0496

NAACP0497

NAACP0498

NAACP0499

NAACP0500

NAACP0501

NAACP0502

NAACP0503

NAACP0504

NAACP0505

NAACP0506

NAACP0507

NAACP0508

NAACP0509

NAACP0510

NAACP0511

NAACP0512

NAACP0513

NAACP0514

NAACP0515

NAACP0516

NAACP0517

NAACP0518

NAACP0519

NAACP0520

NAACP0521

NAACP0522

NAACP0523

NAACP0524

NAACP0525

NAACP0526

NAACP0527

NAACP0528

NAACP0529

NAACP0530

NAACP0531

NAACP0532

NAACP0533

NAACP0534

NAACP0535

NAACP0536