Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1990 - November 30, 1990

165 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1990. 4e7bb225-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a3f78135-908e-40d5-b48c-0af2ddcf4559/petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

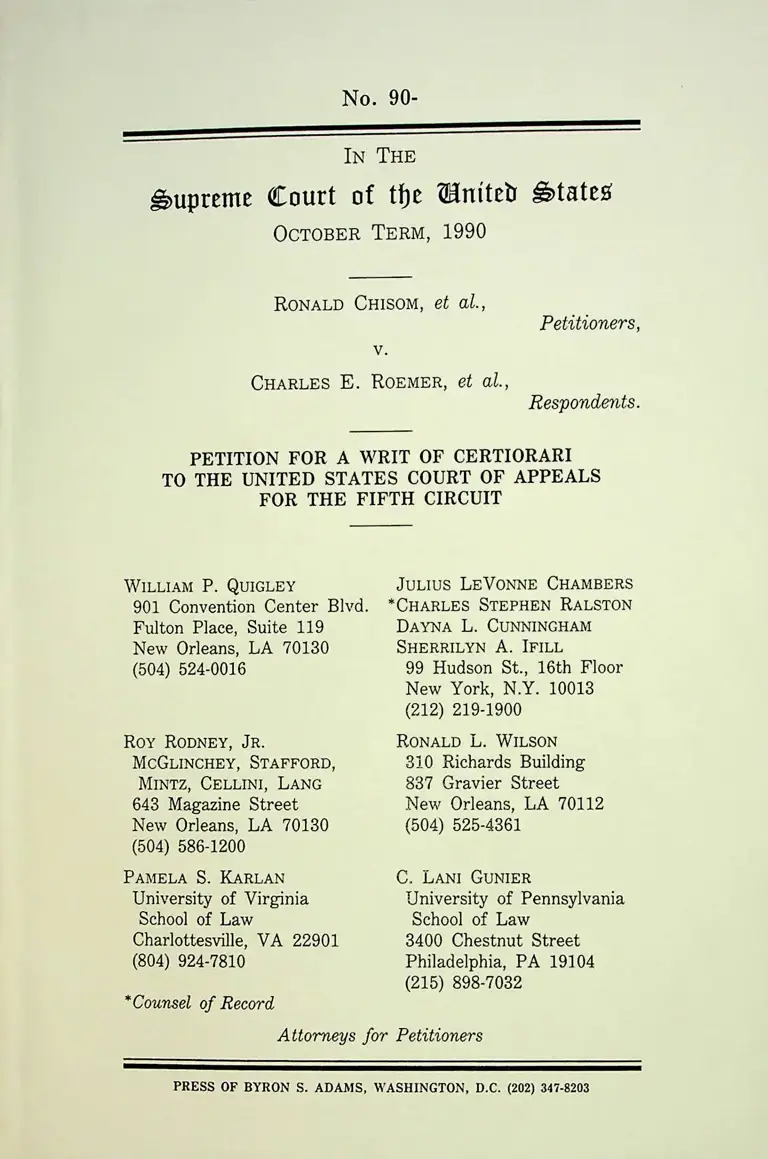

No. 90-

IN THE

giupreme Court of tbe ?guitar §§tateg

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Petitioners,

V.

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

MCGLINCHEY, STAFFORD,

MINTZ, CELLINI, LANG

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

*Counsel of Record

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

*CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. WILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LANI GUNIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTION PRESENTED

Should this Court grant certiorari to resolve a conflict

between the circuits as to whether Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, governs the election of judicial

officers?

111

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

PARTIES

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iv

OPINIONS BELOW 2

JURISDICTION 3

STATUTE INVOLVED 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 4

The Proceedings Below 4

Statement of Facts 7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT 12

THIS CASE PRESENTS AN IMPORTANT ISSUE OF THE

MEANING OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT ON WHICH

THERE IS A CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CIRCUITS . . . 12

A. The Question of Whether Section 2

Governs Judicial Elections is of

National Importance.

B. The Decision of the Fifth Circuit Is

in Square Conflict with the Decision

of the Sixth Circuit in Mallory v.

Eyrich.

CONCLUSION

12

16

19

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Alexander v. Martin, No. 86-1048-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C.) 13

Allen v. Siate Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) 15

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) 10

Brooks v. State Board of Elections, 59 U.S.L. Week 3293

(October 15, 1990) 12, 14

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La.

1987) 2, 5

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La.

1988) 3, 5

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988) . 3, 5, 16

Chisom v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988) . 3, 5

Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285 (M.D. La. 1988) 12

Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), aff'd,

477 U.S. 901 (1986) 14

Hunt v. Arkansas, No. PB-C-89-406 (E.D. Ark. 1989) 13

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) . . . . 10

LULAC v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990) 2, 6,

7, 12-16, 18

Pages:

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988)12, 16, 17

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987) 13

Nipper v. Martinez, No. 90-447-Civ-J-16 (M.D. Fla.

1990) 12

Rangel v. Mattox (5th Cir. No. 89-6226) 12

SCLC v. Siegelman, 714 F. Stipp. 511 (M.D. Ala.

1989) 12, 13

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968) 10

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) 15

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941) 10

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972),

aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) 18

Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696 F. Supp. 1563

(N.D. III. 1988) 13

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) 3

42 U.S.C. § 1973/(c)(1) 17

La. Const. art. V, § 22(b) 10

vi

Pages:

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973 passim

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c 14-17

No. 90-

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

RONALD CHISOM, et at.,

Petitioners,

V.

CHARLES E. ROEls.4ER, et at.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter

Willard, Marc Morial, Henry Dillon Ill, and the Louisiana

Registration/Education Crusade respectfully pray that a writ

of certiorari issue to review the judgment and opinion of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in this

proceeding on November 2, 1990.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Fifth Circuit is not yet reported, and

is set out at pp. la-3a of the appendix hereto ("App."). The

opinion of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana is unreported and is set out at pp. 4a-

64a of the appendix, except for statistical tables that are an

appendix to the district court's opinion. Copies of those

tables have been filed under separate cover with the Clerk of

the Court.

In addition to the opinions in this case, there is set out

at pp. 65a-99a of the appendix hereto the opinion of the

majority of the Fifth Circuit sitting in barn: in LULAC v.

Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990), which is the basis

of the opinion of the Fifth Circuit in this case.

This case was the basis of two earlier appeals; the

previous reported decisions, in chronological order, are as

follows:

C. hisoin v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La. 1987);

1

3

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988),

cert. denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988);

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La.

1988);

Chisom v. Roetner, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988).

JURISDICTION

The decision of the Fifth Circuit was entered on

November 2, 1990. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

This case involves Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, which provides in pertinent

part:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by a State of political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color . . .

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based upon the totality of

circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally open

to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity to participate in

the political process and elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided, That nothing

in this section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Proceedings Below.

This case was brought by African American citizens of

the United States in 1986 under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 and the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution of

the United States.' The plaintiffs, who are voters, attorneys,

'The issue in the case as it reaches this Court involves only the

claims of the petitioners under the Voting Rights Act.

5

and a voter registration and education organization,

challenged the multi-member aspect of the scheme of

election of justices of the Supreme Court of Louisiana by

districts on the ground it denied African Americans an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process.

The district court initially granted the defendants'

motion to dismiss on the ground that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act did not govern the election of judges; this ruling

was reversed by the Fifth Circuit and this Court denied

certiorari. Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp 183 (E.D. La.

1987), reversed, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988).z

After a trial on the merits, the district court held that

the plaintiffs had not established that the method of electing

supreme court justices violated either the Voting Rights Act

20n remand, the district court granted a preliminary injunction

enjoining the state from going forward with an election under the

challenged system, Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F.Supp 1524 (E.D. La.

1988), but this decision was also reversed, by a different panel of the

Fifth Circuit. Chisoni v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988).

6

or the Constitution. (App. pp. 4a-64a.) Petitioners appealed

limited to the question of whether a violation of the Voting

Rights Act had been shown. On November 2, 1990, a

panel of the Fifth Circuit ruled that the Voting Rights Act

does not apply to judicial elections based on the September

29, 1990, in banc Fifth Circuit in LULAC v. Clements, 914

F.2d 620 (App. pp. 65a-99a).3. The "cardinal reason" for

the result in LULAC was that the Voting Rights Act did not

apply to judicial elections because "judges need not be

elected at all." 914 F.2d at 622. App. p. 66a.3 Judges

Higginbotham and Johnson, who were on the panel in the

31n LULAC, after oral argument before a panel of the Fifth Circuit,

the full court, sun sponte, set down the case for rehearing in bane to

decide the issue of whether the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial

elections. By a 7-6 majority the Fifth Circuit overruled its prior decision

in Chisom and held that the results test of Section 2, did not apply to the

election of judges. LULAC v. Clentents, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir.

I990)(App. pp. 65a-99a)

'A petition for writ of certiorari will be filed in LULAC v. Clements

shortly. For the reasons set out in that petition, petitioners here urge that

review be granted in both cases.

7

present case, dissented from that holding of LULAC but

were constrained to rule in Chisom that judicial elections

were not covered at all by Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and that, therefore, the complaint must be dismissed.'

(App. pp. 2a-3a.) This petition followed.

Statement of Facts.

In Louisiana, all but one of the six districts from which

members of the Supreme Court are elected are

geographically defined single member districts and elect one

justice each. The lone multimember district, the First

Supreme Court District ("the First District") elects two

5Judge Higginbotham, joined by three other judges, dissented from

the holding that Section 2 covered no judicial elections, but concurred in

the result in LULAC on other grounds. 914 F.2d at 636. Judge

Johnson, who was the author of the original opinion in the present case,

dissented in LULAC. 914 F.2d at 657. Chief Judge Clark also

concurred in the result in LULAC but not with its holding that no judicial

elections were covered. 914 F.2d at 633.

'As a result of the decision in LULAC, the panel in the present case

did not reach or decide the issue of the correctness of the decision of the

district court on the merits of plaintiffs' claims. If this Court grants

certiorari and reverses the decision below, the appropriate disposition

would be a remand to the court of appeals for a decision on the merits.

8

justices.' App. 7a-8a. With a population of over 1,100,000

and spanning four parishes -- Orleans, St. Bernard,

Plaquemines, and Jefferson -- it is by far the largest supreme

court district, is more than twice the size of the smallest

supreme court district,' and has by far the largest African

American population. The First District is 34.4% African

American in total population and African Americans

comprise 31.61% of the registered voters. App. 10a.

Orleans Parish contains more than half of the population of

the First District and is majority African American in both

total population (55.3%) and in the percentage of registered

voters (51.6%). As of March 3, 1988, 81.2% of African

American registered voters within the First District resided

within Orleans Parish. The other three parishes that make

'The two justices have staggered terms, so that they are chosen in

different elections. Therefore, African American voters are unable to

optimize their political influence by single-shot voting.

'The Louisiana constitution does not require that the election districts

for the Supreme court be apportioned equally by population. Indeed, the

total population deviation between districts is 74.95%, with the 1980

population of the Fourth District being 411,000. App. 10a.

9

up the First District are overwhelmingly white. App. 9a,

13a.

The result of combining the four parishes into one

district from which the entire population elects two supreme

court justices is that white voters are in a substantial

majority, comprising 65.21% of the total population and

69.49% of the voting age population. App. 10a. The First

District could easily be split into two roughly equal supreme

court districts: one, comprised of Orleans Parish,

predominantly African American with a population of

557,515, and the other, comprised of the three remaining

parishes, predominantly white with a population of 544,738.9

App. .10a..

Judicial elections in Louisiana are extremely racially

polarized. Whites vote for white candidates and when given

a choice, African Americans overwhelmingly support

'These two districts would fall well within the range of population of

existing supreme court districts; for example, the Second and Sixth

Districts have populations of 582,223 and 556,383, respectively. App.

10a.

10

African American candidates. White voters consistently fail

to support African American judicial candidates. This

political climate exists against an historical backdrop of

pervasive disenfranchisement on the basis of race.' In

addition, the African American community continues to

suffer a legacy of discrimination that translates into

depressed socio-economic conditions today.

No African American has been elected to the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First District or any other supreme

court district in modern times." Although African

Americans comprise 29% of the state's population, few

African Americans have been elected to other offices within

the First District outside of Orleans Parish. The

'°United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941); Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965); Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964).

See also, Sobol v. Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968) for a vivid

account of discriminatory practices in Plaquemines Parish.

"The only African American to serve on the Louisiana Supreme

Court in this century was appointed to a vacancy on the court for a

period of 17 days during November, 1979. Under the Louisiana

Constitution, he was not permitted to seek election to the seat for which

he had been appointed. See La. Const. art. V, § 22(b).

11

combination of demographic, historical, and socio-economic

factors results in African American voters in the First

District being denied equal opportunity to participate in the

political processes leading to the nomination and election of

justices to the supreme court and therefore to elect

candidates of their choice.

12

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

THIS CASE PRESENTS AN IMPORTANT ISSUE OF THE

MEANING OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT ON W HICH

THERE IS A CONFLICT BETWEEN TIIE CIRCUITS

A. The Question of Whether Section 2 Governs Judicial

Elections is of National Importance.

Cases challenging the election of judges under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act have been brought in

Ohio, 12 Louisiana, I3 Texas," Florida, 15 Alabama, 16 Georgia, 17

I.-Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988)(challenge to the

countywide election of municipal judges in Cincinatti).

"Chisom v. Roemer, supra; Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285

(M.D. La. 1988)(challenge to at-large election of family court, district

court, and court of appeals judges).

"LULAC v. Matto.r, supra; Rangel v. Mortar (5th Cit. No. 89-

6226)(challenge to the multi-county election of judges for the Thirteenth

Court of Appeals).

"Nipper v. Martinez, No. 90-447-Civ-J-16 (M.D. Fla.

1990)(challenge to the at-large election of trial judges in the Fourth

Judicial Circuit).

"SCLC v. Siegelnzan, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989)(challenge

to the numbered post, at-large method of electing circuit and district

court judges).

°Brooks v. Stare Board of Elections, Civ. No. 288-146 (S.D. Ga.

1989)(challenge to at-large method of electing superior court judges under

both Sections 2 and 5 of the Act; summary affirmance by this Court on

Section 5 issues, 59 U.S.L. Week 3293 (October 15, 1990), trial pending

on Section 2 claims).

13

Arkansas,' Illinois," Mississippi, 2° and North Carolina. 21

Before the Fifth Circuit's decisions in this case and LULAC,

in all of these cases courts had held that Section 2 governed

the elections of both trial and appellate court judges.

However, the effect of the decisions in Chisom and LULAC

have already been felt outside of the Fifth Circuit; thus in

SCLC v. Siege/man, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989),

the district.judge recently ordered the parties to file briefs on

the defendants' motion for reconsideration in light of

LULAC.

"Hunt v. Arkansas, No. PB-C-89-406 (E.D. Ark. 1989)(challenge to

the method of electing circuit, chancery, and juvenile court judges in

certain counties).

19Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696 F. Supp. 1563 (N.D. Ill.

1988)(challenge to the at-large method of electing Supreme Court,

Appellate, and Circuit Court judges from Cook County).

'°Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987)(challenge

to the at-large election of judges to state chancery and circuit judges in

three counties; district court found liability under Section 2, single-

member district remedy established resulting in the election of African

Ameriaan judges).

nAlexander v. Martin, No. 86-1048-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C.)(challenge to

the statewide election of state superior court judges; under settlement, ten

African American candidates elected as superior court judges).

14

The opportunity for confusion caused by the decisions

below, and the consequent prejudice to voters' and

candidates' rights in jurisdictions where judicial election

cases are pending, would in itself warrant this Court's

review of this case. Review is made more all the more

imperative in light of this Court's recent affirmance of the

holding in Brooks v. State Board of Elections that Section 5

of the Act covers judicial elections. 59 U.S.L. Week 3293

(October 15, 1990). Brooks reiterated this Court's earlier

affirmance of the holding in Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp.

410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), aff'd, 477 U.S. 901 (1986) that

Section 5 governs judicial elections since "the Act applies to

all voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the

object of the vote." 618 F. Supp. at 413 (emphasis in

original).

As Judge Higginbotham noted in objecting to the

LULAC majority's view that Section 2 does not apply to

judicial elections (concurring opinion):

15

To distinguish the Sections [2 and 5] would lead to

the incongruous result that if a jurisdiction had a

discriminatory voting procedure in place with

respect to judicial elections it could not be

challenged, but if a state sought to introduce that

very procedure as a change from existing

procedures, it would be subject to Section 5

preclearance and could not be implemented.

914 F.2d at 649. Nevertheless, the LULAC majority, since

it had to concede that Section 5 covered the election of

judges (App. 93a), reached precisely this "incongruous

result," one clearly at odds with this Court's directive that

the Act be given its "broadest possible scope." Allen v. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. U.S. 544 (1969). Accord,

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). 22 Certiorari

should be .granted to resolve the confusion created by the

Fifth Circuit's decision of the important issue presented by

Section 2(a) prohibits all States and political

subdivisions from imposing any voting

qualifications or prerequisites to voting or

any standards, practices or procedures which

result in the denial or abridgement of the

right to vote of any citizen who is a member

of a protected class . . . .

478 U.S. at 43 (emphasis in the original).

16

this case, an issue on which this Court has not yet spoken.

B. The Decision of the Fifth Circuit Is in Square Conflict

with the Decision of the Sixth Circuit in Mallory v.

Eyrich.

In its first decision in the present case, Chisom v.

Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056, cert. denied, 488 U.S. , 102

L.Ed.2d 379 (1988), holding that Section 2 covers judicial

elections, the Fifth Circuit relied on substantially the same

reasoning as did the Sixth Circuit in Mallory v. Eyrich, 839

F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988). In overruling Chisom the Fifth

Circuit has placed itself directly in conflict with Mallory.

Compare, e.g., the discussion of Sections 2 and 5 in

Mallory, 839 F.2d at 280 and Chisom, 839 F.2d at 1063-

64, with that in LULAC, App. 93a.

In Mallory, a challenge to the election of Ohio

municipal court judges, the Sixth Circuit concluded that

Section 2 applies to the election of judges based on a

thorough review of the plain language of the statute and the

17

policy behind it, relevant legislative history, and judicial

interpretation of Section 5. 24 In its decision, the Sixth

Circuit unequivocally rejected the reasoning now adopted by

the Fifth Circuit in two critical respects.

First, the Sixth Circuit concluded that there is "no basis

in the language or legislative history of the 1982 amendment

to support a holding" that when it used the word

"representative" in the 1982 amendment, Congress

intentionally engrafted an exception onto Section 2 that

removed judicial elections from the protective measures of

23By its express terms, the original Voting Rights Act of 1965, which

enacted a blanket prohibition against race-based discrimination in voting,

applied to judicial elections. "Vote" or "voting" was defined in the Act

as including "all actions necessary to make a vote effective in any

primary, special or general election, . . . with respect to candidates for

public or party office. . . ." §14(b)(42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1)). Judicial

candidates clearly were "candidates for public or party offices" within the

terms of the Act. When Section 2 was amended in 1982, Congress did

not change a single word in either Section I4(b) or the operative

provisions of the statute that defined its scope. It merely added, in

Section 2(b), a clear standard of proof for the violations outlined in the

old Section 2, which now had become Section 2(a).

As Mallory notes, "Section 5 uses language nearly identical to that

of section 2 in defining prohibited practices -- 'any voting qualification

or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect

to voting.'" 839 F.2d at 280.

18

the Act. 839 F.2d at 280. Compare LULAC, App. 75a-91a.

Second, the Sixth Circuit held that challenges to racially

discriminatory election mechanisms under Section 2 are not

controlled by the rule that the fourteenth amendment's equal

population principle apparently does not apply to judicial

election districts. 839 F.2d at 277-78 (citing Wells v.

Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), aff'd, 409

U.S. 1095 (1973). Compare LULAC, App.80a-88a.

The conflict between the Fifth and Sixth Circuit's

interpretation of the scope and meaning of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act should be resolved by this Court.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted, the decision of the court below

reversed, and the case remanded for a decision on the merits

of petitioners' claims under the Voting Rights Act.

Respectfully submitted,

W ILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center

Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

McGlinchey, Stafford,

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

. School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

-Counsel of Record

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

*CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. W ILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LAN! GUINIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

V.

CHARLES E. "BUDDY" ROEMER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

(November 2, 1990)

Before KING and HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges. •

PER CURIAM:

The plaintiffs in this action originally claimed that

defendants violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution and the Voting

This decision is being made by a quorum. see 28 U.S.C. § 46(d).

2a

Rights Act of 1965, § 2, codified as amended, 42 U.S.C. §

1973 .(Voting Rights Act). The district court ruled against

the plaintiffs on the constitutional claims and the Voting

Rights Act claims. The district court's ruling on the

constitutional claims was not appealed. Thus, there remains

pending before this court an appeal of the district court's

disposition of the Voting Rights Act claims.

In view of the fact that this court, sitting en bane in

Lulac v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990), has

overruled Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1988) (Chisom I), this case is remanded to the district court

with instrtictions to dismiss all claims under the Voting

Rights Act for failure to state a claim upon which relief may

be granted. See Falcon v. General Telephone Co., 815 F.2d

317, 319-20 (5th Cir. 1987) ("[O]nce an appellate court has

decided an issue in a particular case both the District Court

and Court of Appeals should be bound by that decision in

any subsequent proceeding in the same case.... unless..

3a

controlling authority has since made a contrary decision of

law applicable to the issue.") (citations omitted); White v.

Murtha, 377 F.2d 428, 431-32 (5th Cir. 1967). Each party

shall bear its own costs.

REMANDED with instructions. The mandate shall

issue forthwith.

4a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL. CIVIL ACTION

VERSUS NO. 86-4057

CHARLES E. ROEMER, ET AL. SECTION "A"

OPINION

[Filed September 13, 1989]

SCHWARTZ, J.

This Matter came before the Court for nonjury trial.

Having considered the evidence, the parties' memoranda and

the applicable law, the Court rules as follows. To the extent

any of the following findings of fact constitute conclusions

of law, they are adopted as such. To the extent any of the

following conclusions of law constitute findings of fact, they

are so adopted.

Findings of Fact

This is a voting discrimination case. Plaintiffs have

brought this suit on behalf of all black registered voters in

Orleans Parish, approximately 135,000 people, alleging the

5a

present system of electing the two Louisiana Supreme Court

Justices from the New Orleans area improperly dilutes the

voting strength of black Orleans Parish voters. Specifically,

plaintiffs challenge the election of two Supreme Court

Justices from a single district consisting of Orleans,

Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes. Plaintiffs

seek declaratory and injunctive relief under section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973 (West

Stipp. 1989)% and under the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2 provides in pertinent part:

(a) • No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State or political subdivision in a manner which results

in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color . . .

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is

established if, based upon the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not equally

open to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its members

have less opportunity to participate in the political process and

elect representatives of their choice. The extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected to office in

the State or political subdivision is one circumstance which

may be considered: Provided, That nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population.

6a

§1983 (West 1981)2, for alleged violations of rights secured

by the fourteenth' and fifteenth° amendments of the federal

Constitution.'

Section 1983 provides in pertinent part:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

reeulation, custom, or usage, of any State ..., subjects, or

causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or

other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation

of any rights, privileges or immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in

an action at law, suit in equity, or other proceeding for

redress.

The fourteenth amendment provides in pertinent part:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The fifteenth amendment provides in pertinent part:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be

denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on

account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Declaratory relief is also sought under 28 U.S.C. §§2201 and

2202, which provide in pertinent part:

(a) In a case of actual controversy within its jurisdiction,

... any court of the United States, upon the filing of an

appropriate pleading, may declare the rights or other legal

relation of any interested party seeking such declaration,

whether or not further relief is or could be sought.

7a

I.The present Supreme Court Districts and the black

voting population; Minority or majority?

The Louisiana Supreme Court, the highest Court in the

state, presently consists of seven Justices, elected from six

Supreme Court Districts. Each Justice serves a term of ten

years. Candidates for the Louisiana Supreme Court must

have been a resident of that election district for at lease two

(2) years, and each member of the Supreme Court must be

a resident of the election district from which he or she was

elected.' The State imposes a majority-vote requirement for

election to the Supreme Court. Since 1976, every candidate

runs in a single preferential primary, but each candidate's

political party affiliation is indicated on the ballot. If no

single candidate receives a majority of votes in the

preferential primary, the top two candidates with the most

votes in the primary compete in a general election. Five of

the districts elect one Justice each, but one district -- the

See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 19 at p.28.

8a

First Supreme Court District -- elects two Justices.' These

two positions are elected in staggered terms. No Justice is

elected on a state-wide basis, although the Supreme Court

sits en banc and its jurisdiction extends state-wide.' One of

the seats in question is presently held by Justice Pascal F.

Calogero, Jr.; the other is presently held by Justice Walter

F. Marcus, Jr. Judges are not subject to recall elections.'

The five single member election districts consist of

eleven to fifteen parishes; the First Supreme Court District,

as stated above, consists of four parishes. No parish lines

are cut by' the election districts for the Supreme Court.'"

The Louisiana Constitution does not require that the election

districts for the Supreme Court be apportioned equally by

7 See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 18, 21 at pp.28-29.

° See Pre-Trial Order Stipulations 3-6, p.24. See also La. Const.

of 1974, art. 5, §§ 3, 4 & 22A; LSA-RS § 13:101 (West 1983).

° See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 23 at p.29.

I° See id. nos. 9-10 at p.26.

9a

population." However, the Louisiana Constitution does

authorize the state legislature, by a two-thirds vote of the

elected members of each house of the legislature, to revise

the districts used to elect the Supreme Court and to divide

the first district into two single-member districts:2

The New Orleans metropolitan area is composed of

Orleans Parish, which has a majority black electorate, and

several suburban parishes which have majority white elec-

torates. As of March 3, 1988, 81.2 percent of the black

registered voters within the First Supreme Court District

resided within Orleans Parish and 16.0 percent resided in

Jefferson Parish. Only 2.1 percent of the black registered

voters in the First District resided in Plaquemines and St.

Bernard Parishes.

The following two tables set forth specific population

data from the 1980 census:

" See id. no. 12 at p.26.

12 See id. no. 24 at p.29.

10a

(1) For the six Supreme Court election districts:"

Dist- Total Black Total Black

rict# population population(%) VAP" VAP(%)

1 1,102,253 379,101(34.39) 772,772 235,797(30.51)

2 582,223 188,490(32.37) 403,575 118,882(29.46)

3 • 692,974 150,036(21.65) 473,855 92,232(19.46)

4 410,850 134,534(32.75) 280,656 81,361(29.99)

5 861,217 256,523(29.79) 587,428 160,711(27.36)

6 556.383 129,557(23.29) 361,510 78,660(21.76)

TOT. 4,205,900

(2) For the parishes in the First Supreme Court

District:"

Total Black

Parish popula- popula- Total Black

tion tion VAP VAP(%)

Jefferson 454,592 63,001(13.86) 314,334 37,145(11.82)

Orleans 557,515 308,149(55.27) 397,183 193,886(48.81)

Plaque-

mines 26,049 5,540(21.27) 16,903 3,258(19.27)

St.

Bernard • 64,097 2,411( 3.76) 44,352 1,508( 3.40)

As of March 3, 1989, registered voter data compiled by the

" See id. no. 13 at p.26.

" Voting Age Population

" See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 15 at p.27.

1 la

Louisiana Commissioner of Elections indicated the following

population characteristics:

(3) For the six Supreme Court election districts:

District Total registered Black registered

voters voters(%)

1 492,691 156,714 (31.8%)

2 285,469 76,391 (26.8%)

3 379,951 74,667 (19.7%)

4 208,568 59,140 (28.4%)

5 464,699 119,239 (25.7%)

6 305,699 70,178 (23.0%)

(4) For the parishes in the First Supreme Court

District:'

Parish Total registered Black registered

voters voters(%)

Jefferson 202,054 25,064 (12.4%)

Orleans 237,278 127,296 (53.6%)

Plaquemines 14,574 2,796 (19.2%)

St. Bernard 38 785 1 558 ( 4.0%)

TOTAL 492,691 156,714 (31.8%)

According to the 1980 Census, the current configuration

'6 See id. no. 16 at p.28.

12a

of election districts has the following percent deviations'

from the "ideal district"' with a population of 600,843:'9

District # Total

Population

Percent

Deviation

1 1,102,253 [-16.54%] 29

2 582,223 - 3.10%

3 692,974 +15.33%

4 410,850 -31.62%

5 861,217 +43.33%

6 556,383 - 7.40%

17 The percentage deviations appear to have been calculated as

follows:

%deviation = factual district pop.- ideal district pop.) x 100

(ideal district population)

'9 In its review of the memoranda, testimony and exhibits, the Court

was unable to locate any definition of the "ideal district" apart from

reference to population. See Weber Report, Defendants' Exhibit 2, p.48.

The Court therefore accepts the parties' stipulation as to the "ideal

district" with the understanding that other factors of legal significance

may suggest such a district is less than "ideal".

'9 The "ideal district" population of 600,843 is calculated by taking

the total population of all districts (4,205,900) and dividing by seven, the

number of ideal districts.

29 The parties stipulated that District 1 shows a -8.27% deviation

from the "ideal district." See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 14, p.27.

However, the definition of the ideal district is to take the state population

and divide it by the number of districts. The First District elects two

justices, therefore, in a comparison of the First District with the "ideal

district," the First District's deviation should be multiplied by two, since

it elects two justices in what would otherwise be an "ideal" seven district

system,

13a

The relative numbers and population densities of black

persons registered to vote in each parish are also shown in

the parties' stipulations that on December 31, 1988, black

persons constituted a majority of those persons registered to

vote in 226 out of an unspecified number of voting precincts

in Orleans Parish,' whereas in Jefferson Parish black

persons constituted a majority of those persons registered to

vote in only 24 precincts. There are no census tracts in St.

Bernard Parish with a majority black population and there is

only one such census tract in Plaquemines Parish. 22

With Population size as the only stipulated indicia of an

"ideal district", the Court further finds that a district

consisting of just Orleans Parish would demonstrate an

approximate -7.2% deviation from the ideal district, and a

21 See United

registration data does

black precincts. See

22 See United

registration data does

black precincts. See

States' Exhibit 47. The

not alter the number and/or

United States' Exhibit 5.

States' Exhibit 48. The

not alter the number and/or

United States' Exhibit 6.

March 3, 1989 voter

identity of the majority

March 3, 1989 voter

identity of the majority

No. 90-

IN THE

giupreme Court of tbe ?guitar §§tateg

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Petitioners,

V.

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

WILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

MCGLINCHEY, STAFFORD,

MINTZ, CELLINI, LANG

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

*Counsel of Record

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

*CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. WILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LANI GUNIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTION PRESENTED

Should this Court grant certiorari to resolve a conflict

between the circuits as to whether Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, governs the election of judicial

officers?

11

PARTIES

The following were parties in the courts below:

Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter Willard, Marc

Morial, Henry Dillon III, and the Louisiana Voter

Registration/Education Crusade, Plaintiffs;

The United States of America, Plaintiff-Intervenor;

Charles E. Roemer, in his capacity as governor of the

State of Louisiana, W. Fox McKeithen, in his capacity as

Secretary of the State of Louisiana, and Jerry M. Fowler, in

his capacity as Commissioner of Elections of the State of

Louisiana, Defendants.

Pascal F. Calogero, Jr., and Walter F. Marcus, Jr.,

Defendants-Intervenors.

111

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

PARTIES

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES iv

OPINIONS BELOW 2

JURISDICTION 3

STATUTE INVOLVED 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 4

The Proceedings Below 4

Statement of Facts. 7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT 12

THIS CASE PRESENTS AN IMPORTANT ISSUE OF THE

MEANING OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT ON W HICH

THERE IS A CONFLICT BETWEEN THE CIRCUITS . . . 19

A. The Question of Whether Section 2

Governs Judicial Elections is of

National Importance.

B. The Decision of the Fifth Circuit Is

in Square Conflict with the Decision

of the Sixth Circuit in MaHoly v.

Eyrich.

CONCLUSION

12

16

19

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Alexander v. Martin, No. 86-1048-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C.) 13

Allen v. Siate Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) 15

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) 10

Brooks v. State Board of Elections, 59 U.S.L. Week 3293

(October 15, 1990) 12, 14

Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La.

1987) 2, 5

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La.

1988) 3, 5

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988) . 3, 5, 16

Chisom v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988) . 3, 5

Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285 (M.D. La. 1988) 12

Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), aff'd,

477 U.S. 901 (1986) 14

Hunt v. Arkansas, No. PB-C-89-406 (E.D. Ark. 1989) 13

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) . . . . 10

LULAC v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990) 2, 6,

7, 12-16, 18

Pages:

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988)12, 16, 17

Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987) 13

Nipper v. Martinez, No. 90-447-Civ-J-16 (M.D. Fla.

1990) 12

Rangel v. Mattox (5th Cir. No. 89-6226) 12

SCLC v. Siegelman, 714 F. Stipp. 511 (M.D. Ala.

1989) 12, 13

Sobol v. Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968) 10

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) 15

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941) 10

Wells v. Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972),

aff'd, 409 U.S. 1095 (1973) 18

Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696 F. Supp. 1563

(N.D. III. 1988) 13

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) 3

42 U.S.C. § 1973/(c)(1) 17

La. Const. art. V, § 22(b) 10

vi

Pages:

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973 passim

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973c 14-17

No. 90-

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

RONALD CHISOM, et at.,

Petitioners,

V.

CHARLES E. ROEls.4ER, et at.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Ronald Chisom, Marie Bookman, Walter

Willard, Marc Morial, Henry Dillon Ill, and the Louisiana

Registration/Education Crusade respectfully pray that a writ

of certiorari issue to review the judgment and opinion of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered in this

proceeding on November 2, 1990.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Fifth Circuit is not yet reported, and

is set out at pp. la-3a of the appendix hereto ("App."). The

opinion of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Louisiana is unreported and is set out at pp. 4a-

64a of the appendix, except for statistical tables that are an

appendix to the district court's opinion. Copies of those

tables have been filed under separate cover with the Clerk of

the Court.

In addition to the opinions in this case, there is set out

at pp. 65a-99a of the appendix hereto the opinion of the

majority of the Fifth Circuit sitting in barn: in LULAC v.

Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990), which is the basis

of the opinion of the Fifth Circuit in this case.

This case was the basis of two earlier appeals; the

previous reported decisions, in chronological order, are as

follows:

C. hisoin v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp. 183 (E.D. La. 1987);

1

3

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988),

cert. denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988);

Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F. Supp. 1524 (E.D. La.

1988);

Chisom v. Roetner, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988).

JURISDICTION

The decision of the Fifth Circuit was entered on

November 2, 1990. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATUTE INVOLVED

This case involves Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, which provides in pertinent

part:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by a State of political

subdivision in a manner which results in a denial or

abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United

States to vote on account of race or color . . .

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based upon the totality of

circumstances, it is shown that the political

processes leading to nomination or election in the

State or political subdivision are not equally open

to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that

its members have less opportunity to participate in

the political process and elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members of a

protected class have been elected to office in the

State or political subdivision is one circumstance

which may be considered: Provided, That nothing

in this section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Proceedings Below.

This case was brought by African American citizens of

the United States in 1986 under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973 and the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendments to the Constitution of

the United States.' The plaintiffs, who are voters, attorneys,

'The issue in the case as it reaches this Court involves only the

claims of the petitioners under the Voting Rights Act.

5

and a voter registration and education organization,

challenged the multi-member aspect of the scheme of

election of justices of the Supreme Court of Louisiana by

districts on the ground it denied African Americans an equal

opportunity to participate in the political process.

The district court initially granted the defendants'

motion to dismiss on the ground that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act did not govern the election of judges; this ruling

was reversed by the Fifth Circuit and this Court denied

certiorari. Chisom v. Edwards, 659 F. Supp 183 (E.D. La.

1987), reversed, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert.

denied, 488 U.S. , 102 L.Ed.2d 379 (1988).z

After a trial on the merits, the district court held that

the plaintiffs had not established that the method of electing

supreme court justices violated either the Voting Rights Act

20n remand, the district court granted a preliminary injunction

enjoining the state from going forward with an election under the

challenged system, Chisom v. Edwards, 690 F.Supp 1524 (E.D. La.

1988), but this decision was also reversed, by a different panel of the

Fifth Circuit. Chisoni v. Roemer, 853 F.2d 1186 (5th Cir. 1988).

6

or the Constitution. (App. pp. 4a-64a.) Petitioners appealed

limited to the question of whether a violation of the Voting

Rights Act had been shown. On November 2, 1990, a

panel of the Fifth Circuit ruled that the Voting Rights Act

does not apply to judicial elections based on the September

29, 1990, in banc Fifth Circuit in LULAC v. Clements, 914

F.2d 620 (App. pp. 65a-99a).3. The "cardinal reason" for

the result in LULAC was that the Voting Rights Act did not

apply to judicial elections because "judges need not be

elected at all." 914 F.2d at 622. App. p. 66a.3 Judges

Higginbotham and Johnson, who were on the panel in the

31n LULAC, after oral argument before a panel of the Fifth Circuit,

the full court, sun sponte, set down the case for rehearing in bane to

decide the issue of whether the Voting Rights Act applies to judicial

elections. By a 7-6 majority the Fifth Circuit overruled its prior decision

in Chisom and held that the results test of Section 2, did not apply to the

election of judges. LULAC v. Clentents, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir.

I990)(App. pp. 65a-99a)

'A petition for writ of certiorari will be filed in LULAC v. Clements

shortly. For the reasons set out in that petition, petitioners here urge that

review be granted in both cases.

7

present case, dissented from that holding of LULAC but

were constrained to rule in Chisom that judicial elections

were not covered at all by Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act and that, therefore, the complaint must be dismissed.'

(App. pp. 2a-3a.) This petition followed.

Statement of Facts.

In Louisiana, all but one of the six districts from which

members of the Supreme Court are elected are

geographically defined single member districts and elect one

justice each. The lone multimember district, the First

Supreme Court District ("the First District") elects two

5Judge Higginbotham, joined by three other judges, dissented from

the holding that Section 2 covered no judicial elections, but concurred in

the result in LULAC on other grounds. 914 F.2d at 636. Judge

Johnson, who was the author of the original opinion in the present case,

dissented in LULAC. 914 F.2d at 657. Chief Judge Clark also

concurred in the result in LULAC but not with its holding that no judicial

elections were covered. 914 F.2d at 633.

'As a result of the decision in LULAC, the panel in the present case

did not reach or decide the issue of the correctness of the decision of the

district court on the merits of plaintiffs' claims. If this Court grants

certiorari and reverses the decision below, the appropriate disposition

would be a remand to the court of appeals for a decision on the merits.

8

justices.' App. 7a-8a. With a population of over 1,100,000

and spanning four parishes -- Orleans, St. Bernard,

Plaquemines, and Jefferson -- it is by far the largest supreme

court district, is more than twice the size of the smallest

supreme court district,' and has by far the largest African

American population. The First District is 34.4% African

American in total population and African Americans

comprise 31.61% of the registered voters. App. 10a.

Orleans Parish contains more than half of the population of

the First District and is majority African American in both

total population (55.3%) and in the percentage of registered

voters (51.6%). As of March 3, 1988, 81.2% of African

American registered voters within the First District resided

within Orleans Parish. The other three parishes that make

'The two justices have staggered terms, so that they are chosen in

different elections. Therefore, African American voters are unable to

optimize their political influence by single-shot voting.

'The Louisiana constitution does not require that the election districts

for the Supreme court be apportioned equally by population. Indeed, the

total population deviation between districts is 74.95%, with the 1980

population of the Fourth District being 411,000. App. 10a.

9

up the First District are overwhelmingly white. App. 9a,

13a.

The result of combining the four parishes into one

district from which the entire population elects two supreme

court justices is that white voters are in a substantial

majority, comprising 65.21% of the total population and

69.49% of the voting age population. App. 10a. The First

District could easily be split into two roughly equal supreme

court districts: one, comprised of Orleans Parish,

predominantly African American with a population of

557,515, and the other, comprised of the three remaining

parishes, predominantly white with a population of 544,738.9

App. .10a..

Judicial elections in Louisiana are extremely racially

polarized. Whites vote for white candidates and when given

a choice, African Americans overwhelmingly support

'These two districts would fall well within the range of population of

existing supreme court districts; for example, the Second and Sixth

Districts have populations of 582,223 and 556,383, respectively. App.

10a.

10

African American candidates. White voters consistently fail

to support African American judicial candidates. This

political climate exists against an historical backdrop of

pervasive disenfranchisement on the basis of race.' In

addition, the African American community continues to

suffer a legacy of discrimination that translates into

depressed socio-economic conditions today.

No African American has been elected to the Louisiana

Supreme Court from the First District or any other supreme

court district in modern times." Although African

Americans comprise 29% of the state's population, few

African Americans have been elected to other offices within

the First District outside of Orleans Parish. The

'°United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299 (1941); Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965); Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964).

See also, Sobol v. Perez, 289 F. Supp. 392 (E.D. La. 1968) for a vivid

account of discriminatory practices in Plaquemines Parish.

"The only African American to serve on the Louisiana Supreme

Court in this century was appointed to a vacancy on the court for a

period of 17 days during November, 1979. Under the Louisiana

Constitution, he was not permitted to seek election to the seat for which

he had been appointed. See La. Const. art. V, § 22(b).

11

combination of demographic, historical, and socio-economic

factors results in African American voters in the First

District being denied equal opportunity to participate in the

political processes leading to the nomination and election of

justices to the supreme court and therefore to elect

candidates of their choice.

12

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

THIS CASE PRESENTS AN IMPORTANT ISSUE OF THE

MEANING OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT ON W HICH

THERE IS A CONFLICT BETWEEN TIIE CIRCUITS

A. The Question of Whether Section 2 Governs Judicial

Elections is of National Importance.

Cases challenging the election of judges under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act have been brought in

Ohio, 12 Louisiana, I3 Texas," Florida, 15 Alabama, 16 Georgia, 17

I.-Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988)(challenge to the

countywide election of municipal judges in Cincinatti).

"Chisom v. Roemer, supra; Clark v. Edwards, 725 F. Supp. 285

(M.D. La. 1988)(challenge to at-large election of family court, district

court, and court of appeals judges).

"LULAC v. Matto.r, supra; Rangel v. Mortar (5th Cit. No. 89-

6226)(challenge to the multi-county election of judges for the Thirteenth

Court of Appeals).

"Nipper v. Martinez, No. 90-447-Civ-J-16 (M.D. Fla.

1990)(challenge to the at-large election of trial judges in the Fourth

Judicial Circuit).

"SCLC v. Siegelnzan, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989)(challenge

to the numbered post, at-large method of electing circuit and district

court judges).

°Brooks v. Stare Board of Elections, Civ. No. 288-146 (S.D. Ga.

1989)(challenge to at-large method of electing superior court judges under

both Sections 2 and 5 of the Act; summary affirmance by this Court on

Section 5 issues, 59 U.S.L. Week 3293 (October 15, 1990), trial pending

on Section 2 claims).

13

Arkansas,' Illinois," Mississippi, 2° and North Carolina. 21

Before the Fifth Circuit's decisions in this case and LULAC,

in all of these cases courts had held that Section 2 governed

the elections of both trial and appellate court judges.

However, the effect of the decisions in Chisom and LULAC

have already been felt outside of the Fifth Circuit; thus in

SCLC v. Siege/man, 714 F. Supp. 511 (M.D. Ala. 1989),

the district.judge recently ordered the parties to file briefs on

the defendants' motion for reconsideration in light of

LULAC.

"Hunt v. Arkansas, No. PB-C-89-406 (E.D. Ark. 1989)(challenge to

the method of electing circuit, chancery, and juvenile court judges in

certain counties).

19Williams v. State Bd. of Elections, 696 F. Supp. 1563 (N.D. Ill.

1988)(challenge to the at-large method of electing Supreme Court,

Appellate, and Circuit Court judges from Cook County).

'°Martin v. Allain, 658 F. Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss. 1987)(challenge

to the at-large election of judges to state chancery and circuit judges in

three counties; district court found liability under Section 2, single-

member district remedy established resulting in the election of African

Ameriaan judges).

nAlexander v. Martin, No. 86-1048-CIV-5 (E.D.N.C.)(challenge to

the statewide election of state superior court judges; under settlement, ten

African American candidates elected as superior court judges).

14

The opportunity for confusion caused by the decisions

below, and the consequent prejudice to voters' and

candidates' rights in jurisdictions where judicial election

cases are pending, would in itself warrant this Court's

review of this case. Review is made more all the more

imperative in light of this Court's recent affirmance of the

holding in Brooks v. State Board of Elections that Section 5

of the Act covers judicial elections. 59 U.S.L. Week 3293

(October 15, 1990). Brooks reiterated this Court's earlier

affirmance of the holding in Haith v. Martin, 618 F. Supp.

410 (E.D.N.C. 1985), aff'd, 477 U.S. 901 (1986) that

Section 5 governs judicial elections since "the Act applies to

all voting without any limitation as to who, or what, is the

object of the vote." 618 F. Supp. at 413 (emphasis in

original).

As Judge Higginbotham noted in objecting to the

LULAC majority's view that Section 2 does not apply to

judicial elections (concurring opinion):

15

To distinguish the Sections [2 and 5] would lead to

the incongruous result that if a jurisdiction had a

discriminatory voting procedure in place with

respect to judicial elections it could not be

challenged, but if a state sought to introduce that

very procedure as a change from existing

procedures, it would be subject to Section 5

preclearance and could not be implemented.

914 F.2d at 649. Nevertheless, the LULAC majority, since

it had to concede that Section 5 covered the election of

judges (App. 93a), reached precisely this "incongruous

result," one clearly at odds with this Court's directive that

the Act be given its "broadest possible scope." Allen v. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. U.S. 544 (1969). Accord,

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986). 22 Certiorari

should be .granted to resolve the confusion created by the

Fifth Circuit's decision of the important issue presented by

Section 2(a) prohibits all States and political

subdivisions from imposing any voting

qualifications or prerequisites to voting or

any standards, practices or procedures which

result in the denial or abridgement of the

right to vote of any citizen who is a member

of a protected class . . . .

478 U.S. at 43 (emphasis in the original).

16

this case, an issue on which this Court has not yet spoken.

B. The Decision of the Fifth Circuit Is in Square Conflict

with the Decision of the Sixth Circuit in Mallory v.

Eyrich.

In its first decision in the present case, Chisom v.

Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056, cert. denied, 488 U.S. , 102

L.Ed.2d 379 (1988), holding that Section 2 covers judicial

elections, the Fifth Circuit relied on substantially the same

reasoning as did the Sixth Circuit in Mallory v. Eyrich, 839

F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988). In overruling Chisom the Fifth

Circuit has placed itself directly in conflict with Mallory.

Compare, e.g., the discussion of Sections 2 and 5 in

Mallory, 839 F.2d at 280 and Chisom, 839 F.2d at 1063-

64, with that in LULAC, App. 93a.

In Mallory, a challenge to the election of Ohio

municipal court judges, the Sixth Circuit concluded that

Section 2 applies to the election of judges based on a

thorough review of the plain language of the statute and the

17

policy behind it, relevant legislative history, and judicial

interpretation of Section 5. 24 In its decision, the Sixth

Circuit unequivocally rejected the reasoning now adopted by

the Fifth Circuit in two critical respects.

First, the Sixth Circuit concluded that there is "no basis

in the language or legislative history of the 1982 amendment

to support a holding" that when it used the word

"representative" in the 1982 amendment, Congress

intentionally engrafted an exception onto Section 2 that

removed judicial elections from the protective measures of

23By its express terms, the original Voting Rights Act of 1965, which

enacted a blanket prohibition against race-based discrimination in voting,

applied to judicial elections. "Vote" or "voting" was defined in the Act

as including "all actions necessary to make a vote effective in any

primary, special or general election, . . . with respect to candidates for

public or party office. . . ." §14(b)(42 U.S.C. § 19731(c)(1)). Judicial

candidates clearly were "candidates for public or party offices" within the

terms of the Act. When Section 2 was amended in 1982, Congress did

not change a single word in either Section I4(b) or the operative

provisions of the statute that defined its scope. It merely added, in

Section 2(b), a clear standard of proof for the violations outlined in the

old Section 2, which now had become Section 2(a).

As Mallory notes, "Section 5 uses language nearly identical to that

of section 2 in defining prohibited practices -- 'any voting qualification

or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect

to voting.'" 839 F.2d at 280.

18

the Act. 839 F.2d at 280. Compare LULAC, App. 75a-91a.

Second, the Sixth Circuit held that challenges to racially

discriminatory election mechanisms under Section 2 are not

controlled by the rule that the fourteenth amendment's equal

population principle apparently does not apply to judicial

election districts. 839 F.2d at 277-78 (citing Wells v.

Edwards, 347 F. Supp. 453 (M.D. La. 1972), aff'd, 409

U.S. 1095 (1973). Compare LULAC, App.80a-88a.

The conflict between the Fifth and Sixth Circuit's

interpretation of the scope and meaning of Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act should be resolved by this Court.

19

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted, the decision of the court below

reversed, and the case remanded for a decision on the merits

of petitioners' claims under the Voting Rights Act.

Respectfully submitted,

W ILLIAM P. QUIGLEY

901 Convention Center

Blvd.

Fulton Place, Suite 119

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 524-0016

ROY RODNEY, JR.

McGlinchey, Stafford,

Mintz, Cellini, Lang

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

(504) 586-1200

PAMELA S. KARLAN

University of Virginia

. School of Law

Charlottesville, VA 22901

(804) 924-7810

-Counsel of Record

JULIUS LEVONNE CHAMBERS

*CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson St., 16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

RONALD L. W ILSON

310 Richards Building

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

(504) 525-4361

C. LAN! GUINIER

University of Pennsylvania

School of Law

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-7032

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 89-3654

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

V.

CHARLES E. "BUDDY" ROEMER, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

(November 2, 1990)

Before KING and HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges. •

PER CURIAM:

The plaintiffs in this action originally claimed that

defendants violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution and the Voting

This decision is being made by a quorum. see 28 U.S.C. § 46(d).

2a

Rights Act of 1965, § 2, codified as amended, 42 U.S.C. §

1973 .(Voting Rights Act). The district court ruled against

the plaintiffs on the constitutional claims and the Voting

Rights Act claims. The district court's ruling on the

constitutional claims was not appealed. Thus, there remains

pending before this court an appeal of the district court's

disposition of the Voting Rights Act claims.

In view of the fact that this court, sitting en bane in

Lulac v. Clements, 914 F.2d 620 (5th Cir. 1990), has

overruled Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir.

1988) (Chisom I), this case is remanded to the district court

with instrtictions to dismiss all claims under the Voting

Rights Act for failure to state a claim upon which relief may

be granted. See Falcon v. General Telephone Co., 815 F.2d

317, 319-20 (5th Cir. 1987) ("[O]nce an appellate court has

decided an issue in a particular case both the District Court

and Court of Appeals should be bound by that decision in

any subsequent proceeding in the same case.... unless..

3a

controlling authority has since made a contrary decision of

law applicable to the issue.") (citations omitted); White v.

Murtha, 377 F.2d 428, 431-32 (5th Cir. 1967). Each party

shall bear its own costs.

REMANDED with instructions. The mandate shall

issue forthwith.

4a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, ET AL. CIVIL ACTION

VERSUS NO. 86-4057

CHARLES E. ROEMER, ET AL. SECTION "A"

OPINION

[Filed September 13, 1989]

SCHWARTZ, J.

This Matter came before the Court for nonjury trial.

Having considered the evidence, the parties' memoranda and

the applicable law, the Court rules as follows. To the extent

any of the following findings of fact constitute conclusions

of law, they are adopted as such. To the extent any of the

following conclusions of law constitute findings of fact, they

are so adopted.

Findings of Fact

This is a voting discrimination case. Plaintiffs have

brought this suit on behalf of all black registered voters in

Orleans Parish, approximately 135,000 people, alleging the

5a

present system of electing the two Louisiana Supreme Court

Justices from the New Orleans area improperly dilutes the

voting strength of black Orleans Parish voters. Specifically,

plaintiffs challenge the election of two Supreme Court

Justices from a single district consisting of Orleans,

Jefferson, St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes. Plaintiffs

seek declaratory and injunctive relief under section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973 (West

Stipp. 1989)% and under the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

Section 2 provides in pertinent part:

(a) • No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied

by any State or political subdivision in a manner which results

in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on account of race or color . . .

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is

established if, based upon the totality of circumstances, it is

shown that the political processes leading to nomination or

election in the State or political subdivision are not equally

open to participation by members of a class of citizens

protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its members

have less opportunity to participate in the political process and

elect representatives of their choice. The extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected to office in

the State or political subdivision is one circumstance which

may be considered: Provided, That nothing in this section

establishes a right to have members of a protected class

elected in numbers equal to their proportion in the population.

6a

§1983 (West 1981)2, for alleged violations of rights secured

by the fourteenth' and fifteenth° amendments of the federal

Constitution.'

Section 1983 provides in pertinent part:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance,

reeulation, custom, or usage, of any State ..., subjects, or

causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or

other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation

of any rights, privileges or immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in

an action at law, suit in equity, or other proceeding for

redress.

The fourteenth amendment provides in pertinent part:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge

the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States;

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The fifteenth amendment provides in pertinent part:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be

denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on

account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

Declaratory relief is also sought under 28 U.S.C. §§2201 and

2202, which provide in pertinent part:

(a) In a case of actual controversy within its jurisdiction,

... any court of the United States, upon the filing of an

appropriate pleading, may declare the rights or other legal

relation of any interested party seeking such declaration,

whether or not further relief is or could be sought.

7a

I.The present Supreme Court Districts and the black

voting population; Minority or majority?

The Louisiana Supreme Court, the highest Court in the

state, presently consists of seven Justices, elected from six

Supreme Court Districts. Each Justice serves a term of ten

years. Candidates for the Louisiana Supreme Court must

have been a resident of that election district for at lease two

(2) years, and each member of the Supreme Court must be

a resident of the election district from which he or she was

elected.' The State imposes a majority-vote requirement for

election to the Supreme Court. Since 1976, every candidate

runs in a single preferential primary, but each candidate's

political party affiliation is indicated on the ballot. If no

single candidate receives a majority of votes in the

preferential primary, the top two candidates with the most

votes in the primary compete in a general election. Five of

the districts elect one Justice each, but one district -- the

See Pre-Trial Order Stipulation 19 at p.28.

8a

First Supreme Court District -- elects two Justices.' These

two positions are elected in staggered terms. No Justice is

elected on a state-wide basis, although the Supreme Court

sits en banc and its jurisdiction extends state-wide.' One of

the seats in question is presently held by Justice Pascal F.

Calogero, Jr.; the other is presently held by Justice Walter

F. Marcus, Jr. Judges are not subject to recall elections.'

The five single member election districts consist of

eleven to fifteen parishes; the First Supreme Court District,