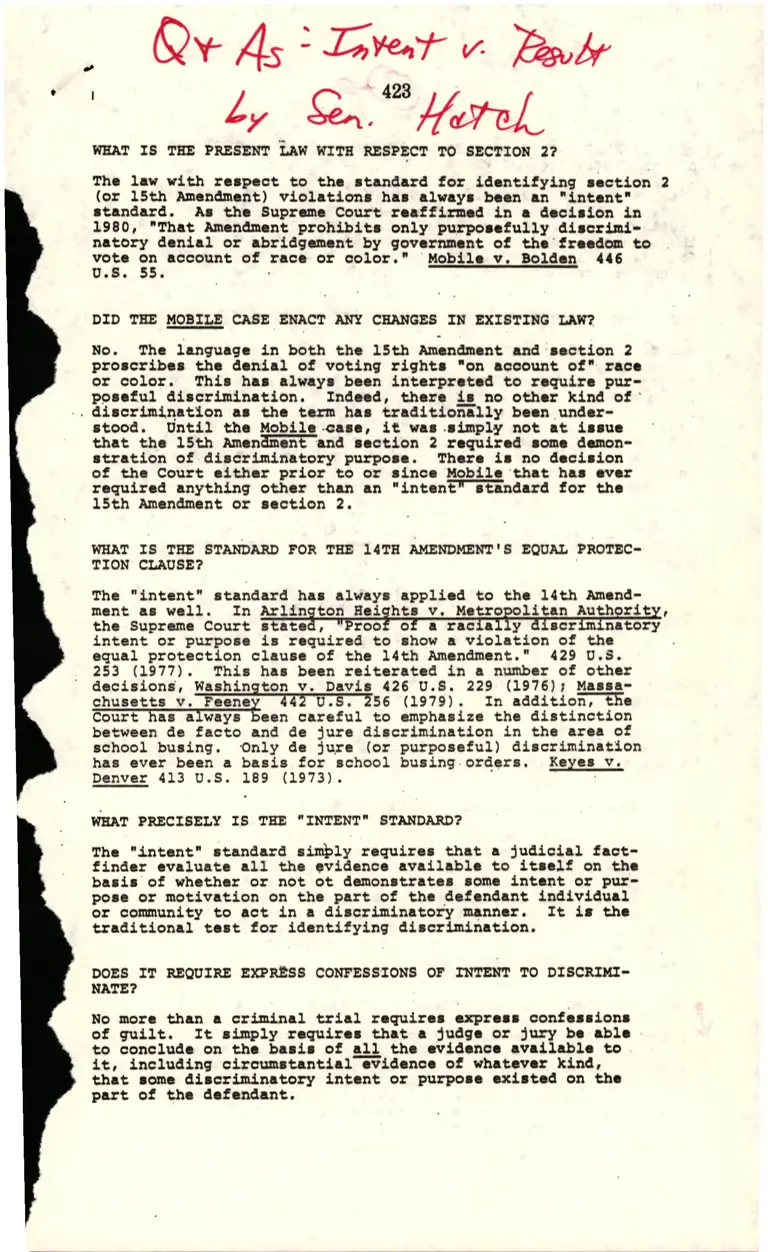

Legal Research on Intent Versus Result by Senator Hatch

Unannotated Secondary Research

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legal Research on Intent Versus Result by Senator Hatch, 1982. 23074626-e192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a4c9f080-3a8b-41a7-a6d3-bc9a0555cc04/legal-research-on-intent-versus-result-by-senator-hatch. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

@V’ 45 :Ey‘ea'f V- gavéf’

“I 1y &\ " 423 gm

WHAT IS THE PRESENT LAW WITH RESPECT TO SECTION 2?

The law with respect to the standard for identifying section 2

(or 15th Amendment) violations has always been an "intent"

standard. As the Supreme Court reaffirmed in a decision in

1980, "That Amendment prohibits only purposefully discrimi-

natory denial or abridgement by government of the freedom to

voge 3; account Of. race or color." Mobile v. Bolden 4‘6

U . """""“"'

DID THE MOBILE CASE_ENACT ANY CHANGES IN EXISTING LAW?

No. The language in both the 15th Amendment and section 2

proscribes the denial of voting rights “on account of“ race

or color. This has always been interpreted to require pur-

poseful discrimination. Indeed, there is no other kind of‘

. discrimination as the term has traditionally been under-

stood. Until the Mobile case, it was simply not at issue

that the 15th Amendment-and section 2 required some demon-

stration of discriminatory purpose. There is no decision

of the Court either prior to or since Mobile that has ever

required anything other than an "intent" standard for the

15th Amendment or section 2.

WHAT IS THE STANDARD FOR THE 14TH AMENDMENT'S EQUAL IPROTEC-

TION CLAUSE?

The "intent" standard has always applied to the 14th Amend-

ment as well. In Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Authgritz,

the Supreme Court state , roo c a rac a y scr natory

intent or purpose is required to show a violation of the .

equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment." 429 U.S.

253 (1977). This has been reiterated in a number of other

decisions, Washin ton v. Davis 426 U.S. 229 (1976)) Massa-

chusetts v. Eeene 132 U.S. 256 (1979). In addition, the

Court Eas aIways §een careful to emphasize the distinction

between de facto and de jure discrimination in the area of

school busing. Only de jure (or purposeful) discrimination

has ever been a basis for school busing orders. Reyes v.

Denver 413 U.S. 189 (1973). ’ -

WEAT PRECISELY IS THE "INTENT" STANDARD?

The "intent'I standard simply requires that a judicial fact-

finder evaluate all the evidence available to itself on the

basis of whether or not ot demonstrates some intent or pur-

pose or motivation on the part of the defendant individual

or community to act in a discriminatory manner. It is the

traditional test for identifying discrimination.

DOES IT REQUIRE EXPRESS CONFESSIONS OF INTENT TO DISCRIMI-

NATE?

No more than a criminal trial requires express confessions

of guilt. It simply requires that a judge or jury be able

to conclude on the basis of all the evidence available to

it, including circumstantial evidence of whatever kind,

that some discriminatory intent or purpose existed on the

part of the defendant.

(@9

THEN IT DOES NOT REQUIRE "MIND-READING" AS SOME OPPONENTS

OF THE "INTENT" STANDARD HAVE SUGGESTED?

Absolutely not. 'lntent' is proven without "mind-reading'l

thousands of times every day of the week in criminal and

civil trials across the country. Indeed, in criminal trials

the existence of intent must be proven "beyond a reasonable

doubt". In the civil rights area, the normal test is that-

intent be proven merely "by a preponderance of the evidence".

WEAT KIND OF EVIDENCE CAN BE USED TO DEMONSTRATE "INTENT"?

Again, literally any kind of evidence can be used to satisfy

this requirement. As the Supreme Court noted in the Arlington

Heights case, "Determining whether invidious'discriminatory

purpose was a motivating factor demands a sensitive inquiry

into such circumstantial and direct evidence as may be avail-

able. 429 U.S. 253, 266. Among the specific considerations

that it mentions are the historical background of an action,

the sequence of events leading to a decision, the existence

of departures from normal procedures, legislative history,

the impact of a decision upon minority groups, etc.

DO YOU MEAN THAT THE ACTUAL IMPACT OR EFFECTS OF AN ACTION

UPON MINORITY GROUPS CAN BE CONSIDERED UNDER THE "INTENT"

TEST?

Yes. Unlike a "results" or "effects"-oriented test, however,

it is not dispositive of a voting rights violation in and of

itself, and it cannot effectively shift burdens of proof in

and of itself. It is simply evidence of whatever force it

communicates to the fact-finder.

WHY ARE sous PROPOSING 'ro SUBSTITUTE A NEW "RESULTS" use In

sscuuon 2? .V ,_ '

Ostensibly, it is argued that voting rights violations are more

difficult to prove under an “intent" standard than they would be

under a "results" standard. ' '

BOW IMPORTANT SHOULD TEAT CONSIDERATION BE?

Completely apart from’the fact that the Voting Rights Act has

been an effective tool for_combatting voting discrimination

under the present standard, it is debatable whether or not

an appropriate standard should be fashioned on the basis of

what facilitates successful prosecutions. Elimination of the

"beyond a reasonable doubt" standard in criminal cases, for

example, would certainly facilitate convictions. We have

chosen not to adopt it because there are competing values,

e.g. fairness and due process.

WHAT IS WRONG WITH THE "RESULTS" STANDARD?

‘ First of all, it is totally unclear what the 'results' stan-

dard is supposed to represent. It is a standard totally un-

known to present law. To the extent that its legislative

history is relevant, and to the extent that it is designed

to be similar to an "effects"_test, the main objection is

that it would establish as a standard for identifying sec-

tion 2 violations a "proportional representation by race"

standard.

425

WHAT IS MEANT SY "PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION SI RACE"?

The "proportional representation by race" standard is one_

that evaluates electoral actions on the basis of whether or

not they contribute to representation in a State legislature

or a City Council or a County Commission or a Ichool board

for racial and ethnic groups in proportion to their exis-

tence in the population.

WHAT IS WRONG WITH "PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION SY RACE"?

It is a concept totally inconsistent with the traditional no-

tion of American representative government wherein elected

officials represent individual citizens not racial or ethnic

groups or blocs. In addition, as the Court observed in Mobile.

the Constitution "does not require proportional represenEaEion

as an imperative of political organization.

COMPARE THEN THE "INTENT" AND THE "RESULTS" TESTS?

The "intent“ test allows courts to consider the totality of

evidence surrounding an alleged discriminatory action and .

then requires such evidence to be evaluated on the basis of

whether or not it evinces someIpurpose or motivation to dis-

criminate. The "results" test, however, would focus analysis

upon whether or not minority groups were represented propor-

tionately or whether or not some change in voting law or pro-

cedure would contribute toward that result.

WHAT DOES TEE TERM 'DISCRIMINATORY RESULTS'I MEAN?

It means nothing morg than is meant by the concept of racial

balance or racial quotas. Under the "results" standard, actions

would be judged, pure and simple, on color-conscious grounds.

This is totally at odds with everything that the Constitution

has been directed towards since the Reconstruction Amendments,

brown v. board of Education, and the Civil Rights Act of 196‘.

e erm scr na cry results" is Orwellian in the sense

that it radically transforms the concept of discrimination

from a process or a means into an end or a result.

ISN'T TEE "PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION SI RACE'I DESCRIPTION

AN EXTREME DESCRIPTION? ‘

Yes, but the "results" test is an extreme test. It is based

upon Justice Thurgood Marshall's dissent in the Mobil case

which was described by the Court as follows: "The ecry of

this dissenting opinion... appears to be that every ‘political

. group' or at least every such group that is in the minority

has a federal constitutional.right tolelect candidates in

proportion to its numbers." The house Report, in discussing

the proposed new "results" test, admits that proof of the

ebzenoe of proportional representation."would be highly

re evant .

SUT DOESN'T THE PROPOSED NEW SECTION 2 LANGUAGE EXPRESSLY

STATE THAT PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION IS NOT ITS OBJECTIVE?

There is. in fact, a disclaimer provision of sorts. It is

clever,.but it is a smokescreen. It states, "The fact that

426

members of a minority group have not been elected in numbers

equal to the group's proportion of the population shall not,

in and of itself, constitute a violation of this section.“

WHY IS THIS LANGUAGE A "SMOKESCREEN"?

The key, of course, is the "in and of itself" language. In

Mobile, Justice Marshall sought to deflect the "proportional

representation by race" description of his "results" theory

with a similar disclaimer. Consider the response of the

Court, "The dissenting opinion seeks to disclaim this de-

scription of its theory by suggesting that a claim of vote

dilution may require, in addition to proof of electoral de-

feat, some evidence of 'historical and social factors' indi-

cating that the group in question is without political in-_

fluence. Putting to the side the evident fact that these

gauzy sociological considerations have no constitutional

basis, it remains far from certain that they oculd, in _

any principled manner, exclude the claims of any discrete group

that happens for whatever reason, to elect fewer of its candi-

dates than arithmetic indicates that it might. Indeed, the

putative limits are bound to prove illusory if the express pur-

pose informing their application would be, as the dissent

wassumes, to redress the 'inequitable distribution of political

influence'."

EXPLAIN FURTHER?

In short, the point is that there will always be an additional

iota of evidence to satisfy the "in and o itself" language.

This is particular true since there is no standard by which

to judge any evidence except for the "results" standard.

WHAT ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE, ALONG WITH EVIDENCE OF THE LACK OF

PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION, WOULD-SUFFICE TO COMPLETE A ‘

SECTION 2 VIOLATION UNDER THE "RESULTS“ TEST?

Among the additional bits of "objective" evidence to which

the House Report-refers are a "history of discrimination",

“racially polarity voting" (sic), at-large elections, majoe

rity vote requirements, prohibitions on single-shot voting,

and numbered posts. Among other factors that have been‘

considered relevant by the Justice Department's Civil Rights

Division in the past in evaluating submissions by "covered"

jurisdictions under section 5 of the Voting Rights Act are

disparate racial registration figures, history of English-

only ballots, maldistribution of services in racially defi-

nable neighborhoods, staggered electoral terms, municipal

elections which "dilute" minority voting strength, the

existence of dual school systems in the past, impediments

to third party voting, residency requirements, redistricting

plans which fail to "maximize“.minority_influence, numbers

of minority registration officials, re-registration or

registration purging requirements, economic costs associ-

ated with registration, etc., etc.

THESE FACTORS HAVE BEEN USED BEFORE?

Yes. In virtually every case, they have been used by the

Justice Department (or by the courts) to determine the exis-

tence of discrimination in "covered" jurisdictions. It is

a matter of one's imagination to come up with additional

427

factors that could be used by creative or innovative courts

or bureaucrats to satisfy the "objective" factor requirement

of the "results" test (in addition to the absence of pro-

portional representation). Bear in mind again that the pur-

pose or motivation behind such voting devices-or arrangements

would be irrelevant.

SUMMARIZE AGAIN THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THESE "OBJECTIVE" FACTORS?

The significance is simple-- where there is a State legislature‘

or a City Council or a County Commission or a School Board which

does not reflect racial proportions within the relevant populatior

that jurisdiction will be vulnerable to prosecution under section

2. It is virtually inconceivable that the "in and of itself''

language will not be satisfied by one or more "objective" factors

existing in nearly any jurisdiction in the country. The exis-

tence of these factors, in conjunction with the absence of pro-

portional representation, would represent an automatic trigger

in evidencing a section 2 violation. As the MoEiIe court, the

disclaimer is "illusory".

BUT WOULDN'T YOU LOOK TO THE TOTALITY OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES?

Even if you did, there would be no judicial standard other than

proportional representation. The notion of looking to the

totality of circumstances is meaningful only_in the context

of some larger state-of-mind standard, such as intent. It is

a meaningless notion in the context of a result-oriented stan-

dard. After surveying the evidence under the present standard,

the courts ask themselves, "Does this evidence raise an infer-

ence of intent?" Under the proposed new standard, given the

absence of proportional representation and the existence of

some "objective'l factor,_a prima facie case has been estab-

lished. There is no need for further inquires by the court.

WHERE WOULD THE BURDEN OF PROOF LIE UNDER THE "RESULTS" TEST?

Given the absence of proportional representation and the exis-

tence of some "objective" factor, the effective burden of '

proof would be upon the defendant community. Indeed, it is

unclear what kind of evidence, if any, would suffice to V

overcome such evidence. In Mobile, for example, the absence

of discriminatory purpose and the existence of legitimate,

non-discriminatory reasons for the at-large system of muni-

cipal elections was not considered relevant evidence by

either the plaintiffs or the lower Federal courts.

PUTTING ASIDE THE ABSTRACT PRINCIPLE FOR THE MOMENT, WHAT IS

THE MAJOR OBJECTIVE OF THOSE ATTEMPTING TO OVER-RULE MOBILE

AND SUBSTITUTE A "RESULTS" TEST IN SECTION 2?

The immediate purpose is to allow a direct assault.upon the

majority of municipalities in the country which have adopted

at-large elections for city councils and county commissions.

This was the precise issue in Mobile, as a matter of fact.

Proponents.of the "results" test argue that at-large elections

tend to discriminate against minorities who would be more

capable of electing "their" representatives to office on a

district or ward voting system. In Mobile, the Court re-

fused to order the disestablishment of the at-large muni-

cipal form of government adopted by the city.

93-706 0 - 83 - 28

428

D0 AT-LARGE SYSTEMS OF VOTING DISCRIMINATE AGAINST MINORITIES?

Completely apart from the fact that at-large voting for muni-

cipal governments was instituted by many communities in the

1910's and 1920's in response to unusual instances of corrup-

ticn within ward systems of government, there is absolutely

no evidence that at-large voting tends to discriminate against

minorities. That is, unless the premise is adopted that only

blacks can represent blacks, only whites can represent whites,

and only hispanics can represent Hispanics. Indeed, many

political scientists believe that the creation of black wards

or Hispanic wards, by tending to create political 'ghettces'

minimise the influence of minorities. It is highly debatable

EfiaE SIack influence, for example, is enhanced by the creation

of a single 90! black ward (that may elect a black person)

thaany three 30! black wards (that may all elect white per-

sons .

WHAT ELSE Is WRONG WITH THE PROPOSITION THAT AT-LARGE ELECTIONS

ARE-CONSTITUTIONALLY INVALID? .

First, it-turns the traditional objective of the Voting Rights

Act-- equal access to the electoral process-- on its head. As

the Court said in Mobile, "this right to equal participation in

the electoral process does not protect any political group,

however defined, from electoral defeat." ‘second, it encou-

rages political isclaticn among minority groups) rather than

having to enter into electoral coalitions in order to elect

candidates favorable to their interests, ward-only elections

tend to allow minorities the more comfortable, but less ulti-

mately influential, state of affairs of safe, racially

.identifiable districts. Third, it tends to place a pre-

mium upon minorities remaining geographically segregated.

To the extent thst integration occurs, ward-only voting

would tend not to result in proportional representation.

To summarize again by referring to Mobile, ”political groups

do notihav: an independent ccnstituEIonaI claim to repre-

sentat on.

WHAT WOULD BE THE IMPACT OF A CONSTITUTIONAL OR STATUTORY

RULE PROSCRIBING AT-LARGE MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS?

The impact would be profound. In Mobile, the plaintiffs

sought to strike down the entire form of municipal govern-

ment adopted by the city on the basis of the at-large form

of city council election. The Court stated, "Despite re-

peated attacks upon multi-member (at-large) legislative

districts, the Court has consistently held that they are

not unconstitutional." If Mobile were over-ruled, the

at-large electoral structures of the more than 2/3 of

the 18,000+ municipalities in the country that have .

adopted this form of government, would be placed in

serious jeopardy.

WHAT WILL BE THE IMPACT OF THE "RESULTS? TEST UPON RE-DIITRICTIRC

AND RE-APPORTIONMENT? . Z .

Re-districting and re-appcrtionment actions will also be judged

on the basis of the proportional representation criterion. The

New York Times, for example, in describing New York City's re-

districting difficulties recently stated, "Lawyers for some of

those who brought suit against the Council under the Voting

Rights Act pointed out that statistics do not guarantee the

election of minority group members. "It's twelve districts

429

on paper, but at best it may be ten, maybe only nine, said

Cesar A. Perales, general counsel to the Puerto Rican Legal

Defense Fund." Minority groups alone will be largely immune

to political or ideological gerrymandering on. the grounds of

"vote dilution" .

WHAT IS "VOTE DILUTION'?

The concept‘of "vote dilution" is one that has been responsible

for transforming other provisions of the Voting Rights Act (esp.

section 5) from those designed simply to ensure equal access by

minorities to the registration and voting processes int to tfiose

concerned with electoral outcome and electoral success as well.

The right to register and vote Has been signific antIy trans-

formed in recent years into the right to cast an "effective" ,

vote and the right of racial and ethnic groups not to have

their collective vote "diluted". The concept of “vote dilution"

'in the section_5 context is separate from the section 2 issue,

‘except that this concept is likely to be borrowed by the courts

in implementing the new "results" test should it be adopted in

section 2. See Thernstrom, “The Odd Evolution of the Voting

Rights Act", 55 The Public Interest 49.

ARE THERE ANY OTHER CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES INVOLVED WITH SECTION 2?

Since section 2 is the statutory expression of the 15th Amendment,

and since both provisions have been interpreted by the Court in

Mobile to require some evidence of intentional discrimination,

tfiere is a major constitutional question whether or. not Congress

can alter this by simple statute. Similar constitutional issues

are involved in pending efforts by Congress to overturn the Roe

v. Wade by defining "person" for purposes of the 14th Amendment.

Beyond the question of conflict with a Supreme Court decision,

there is the constitutional question whether or not Congress

possesses the authority to establish a standard for section 2

violations in excess of its 15th Amendment authority.

WHO CAN INITIATE ACTIONS UNDER SECTION 2?

In addition to prosecution by the Justice Department, section 2

would permit private causes of action against communities. Indi-

viduals er so-calle'd_ 'public interest' litigators could bring

such actions. '

WHAT IS THE POSITION OF THE ADMINISTRATION ON THE SECTION 2 ISSUE?

The Administration and the Justice Department are strongly on

record as favoring retention of the intent standard in section 2.

President Reagan has expressed his concern that the "results"

standard may lead to the establishment of racial quotes in the

- electoral process. Press Conference, December 17, 1981.

SUMMARIZE THE SECTION.2 ISSUE?

The debate over whether or not to overturn the Supreme Court's

decision in Mobile v. Bolden, and establish a “results" test

for the present "Intent' test in the Voting Rights Act, is

probably the single most important constitutional issue that

will be considered by the 97th Congress. Involved in this

controversy are fundamental issues involving the nature of

American representative democracy, federalism, civil rights,

and the relationship between the branches of the national

government.

430

MISCELLANEOUS TABLES

SECTION 5-SUBMISSIONS, BY STATE

The following chart shows the number of proposed changes ifl‘state

election laws submitted to the Justice Department as required by the

Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the number of changes to which the Justice

Department has objected:

Proposed election low changes

1976-00

Alcbcmo

Alcsko’

Arizonc‘

Cclifomic'

Colorodc'

Cenmcficu"

Floridc‘

‘ Georgia

chcii'

1 Idaho‘

Louisiana

Maine

Massachusetts:

Michigarfi

Mississippi

New Hampshire:

New Mexico'

New York‘

Oklahoma‘

Nonh Corolino‘

South Carolina

South More

Texas

Virginia

Wyoming‘

TONI

965-70‘

614

0

201

12

834

249

I ,093

1

1971-75

1 ,OS5

65

326

1

71 1

I .260

6

1 5,959

1 ,780

0

Tovel

1,715

37

1,738

695

233

0

168

3,091

9

1

2,596

3

17

3

1,189

0

65

492

1

1,190

2,402

6

16,208

2.930

1

34.798

Justice

Depenmem

obiectiens

-‘ N

U N ‘4

OOOOOOOOOOOMOON

~4

ndfiouoo

130

14

0

a;

' The pre-cleoronce requirement. requiring submissions of proposed electron law changes to

the Justice Department. was enacted in 135, The provision was conunued through the

extensions 0/ the act in 1970 and 1975.

' Selected county or counties covered rather than entire sects.

’ Selected town or town covered rather than entire state.

' Entire stole covered 135-68.- celccled election districts covered 1970- 72: entire uate covered

since 1975.

‘ Selected county or counties covered until 1975; entire store now covered.

- Not covered [or years indicated.

Source: U.S. Depenmom o! Junk.