State of Louisiana v. George Brief for Defendant, Relator-Appellant in Support of Application for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus and Prohibition

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. State of Louisiana v. George Brief for Defendant, Relator-Appellant in Support of Application for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus and Prohibition, 1964. a28658ce-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a5910a83-18d0-4ca2-8a6c-b80d79a1d731/state-of-louisiana-v-george-brief-for-defendant-relator-appellant-in-support-of-application-for-writs-of-certiorari-mandamus-and-prohibition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

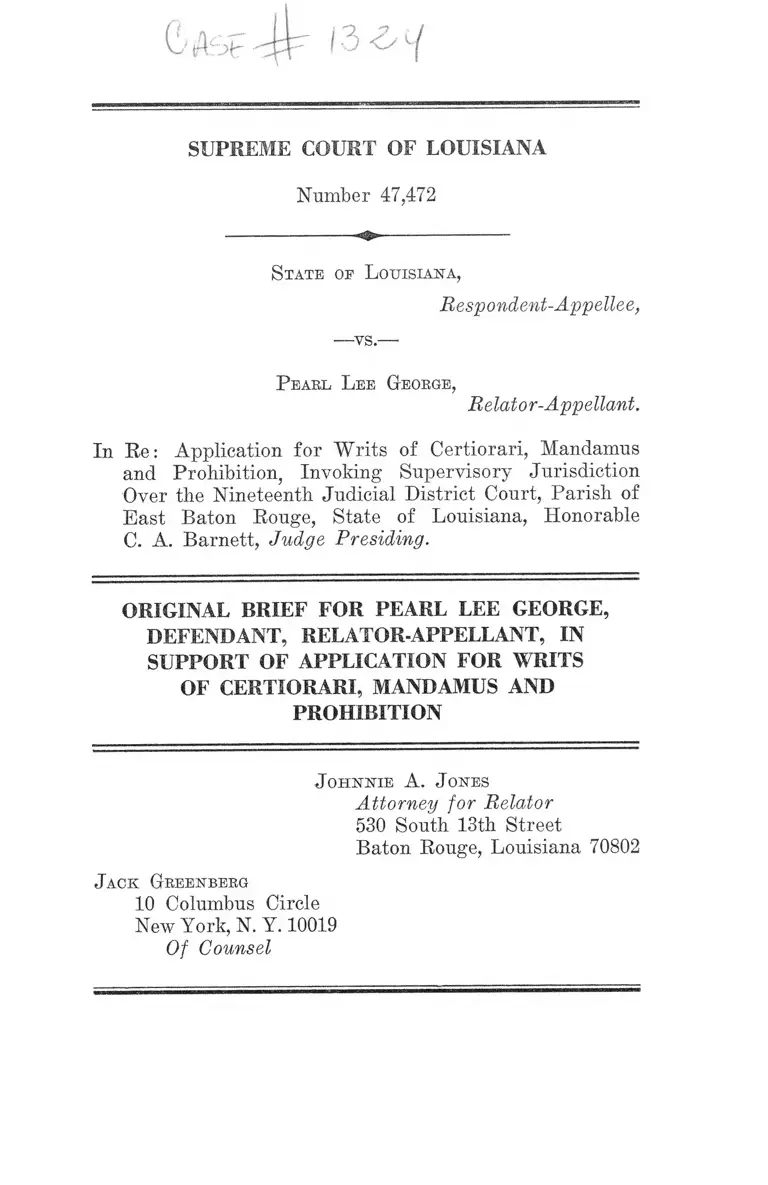

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Number 47,472

S tate op L ouisiana,

Respondent-Appellee,

-vs-

P earl L ee George,

Relator-Appellant.

In Re: Application for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus

and Prohibition, Invoking Supervisory Jurisdiction

Over the Nineteenth Judicial District Court, Parish of

East Baton Rouge, State of Louisiana, Honorable

C. A. Barnett, Judge Presiding.

ORIGINAL BRIEF FOR PEARL LEE GEORGE,

DEFENDANT, RELATOR-APPELLANT, IN

SUPPORT OF APPLICATION FOR WRITS

OF CERTIORARI, MANDAMUS AND

PROHIBITION

J o h n n ie A. J ones

Attorney for Relator

530 South 13th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Jurisdiction .............................. .......................................... 1

Syllabus — ...................................... -.................. ............ 2

Statement of the Case ...................—-.............................. 3

Specification of Errors ........ .............. ...... ..... -.......... -..... 1

A rgum ent :

The Arrest and Conviction of Appellant for Dis

turbing the Peace Violated Her 14th. Amendment

Constitutional Eights in that:

1) There Was No Evidence of Her Commission

of the Crime Charged, in Violation of Due

Process of L a w .................................................. 5

2) The Broadness and Vagueness of the Statute

Effectively Prohibits Constitutionally Pro

tected Rights in Violation of Due Process

of L a w .................................................................. 7

3) The Statute Permits the Indirect Invasion

of Appellant’s Right to the Equal Protection

of the Law s.......................................................... 9

Certificate ............................................. - .................. ....... 1-3

T able oe A uthorities

Cases:

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226 (1964) .......................... 12

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S. 715

(1961) .................-.....................................- ...................... 2,9

PAGE

ii

City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (4th Cir.

1957), affirming 149 F. Snpp. 562 (M. D. N. C., 1957) ..2,10

City of New Orleans v. Adams, 321 F. 2d 493 (5th Cir.

1963) .............................................................. 2,9

Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga.,

1960) ....................... 2,10

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert. den. 353 U. S. 924 (1957) ____ ______ __ _____ 2, 9

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963) ....2, 6, 8

Garner et al. v. State of Louisiana, 368 IT. S. 157

(1961) ........................ ...... ........ ......... ........................ . 2,6

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 (1939) ............... 2, 7

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 (1963) ...............2,10

State ex rel. Dowling v. Ray, 150 La. 1030, 91 So. 443

(1922) .... 1

State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d 778 (1943) .... 2, 8

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U. S. 154 (1962) ..... ............. 6

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 IT. S. 199 (1960) ------------ 2, 5

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88, 97-98 (1940) ------ 2, 8

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 IT. S. 350 (1962) .......2,10

United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217 (1934) ..... ..... 12

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88 (1871) .... 12

PAGE

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) 2,7

Ill

Statutes:

Civil Rights Act of 1964, §201, 78 Stat. 243 ................. 10

Civil Rights Act of 1964, §203, 78 Stat. 244 .................. 11

Constitution of Louisiana of 1921, Article 7, Section 10 1

LSA-R. S. 14:26 of 1950, as amended.............................. 1

LSA-R. S. 14:103.1 of 1950, as amended.... .................. 1,4,5

O th er A u thority

110 Cong. Rec. 9463 (daily ed. May 1, 1964) ............... 11

PAGE

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA

Number 47,472

S tate oe L ouisiana,

Respondent-Appellee,

■—vs.—■

P earl L ee George,

Relator-Appellant.

In Re: Application for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus

and Prohibition, Invoking Supervisory Jurisdiction

Over the Nineteenth Judicial District Court, Parish of

East Baton Rouge, State of Louisiana, Honorable

C. A. Barnett, Judge Presiding.

ORIGINAL BRIEF FOR PEARL LEE GEORGE,

DEFENDANT, RELATOR-APPELLANT, IN

SUPPORT OF APPLICATION FOR WRITS

OF CERTIORARI, MANDAMUS AND

PROHIBITION

Jurisdiction

This case is predicated on LSA-R. S. 14:26 and LSA-

R. S. 14:103.1 of 1950, as amended, criminal conspiracy for

the specific purpose of committing a criminal mischief, and

particularly to disturb the piece.

This court has supervisory jurisdiction over criminal

courts under Section 10, Article 7, The Constitution, State

of Louisiana of 1921, and Section 7, Rule 12 of this court.

State ex rel. Dowling v. Ray, 150 La. 1030, 91 So. 443

(1922).

2

Syllabus

The Arrest and Conviction of Appellant for Disturbing

the Peace Violated Her 14th Amendment Constitutional

Rights in that:

1) There was no evidence of her commission of the crime

charged, in violation of due process of law.

Garner et al. v. State of Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157

(1961); Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960);

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 (1963).

2) The breadth and vagueness of the statutes effectively

prohibits constitutionally protected rights in violation

of due process of law.

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963); Lametta v.

New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 (1939); Thornhill v. Ala

bama, 310 IT. S. 88, 97-98 (1940); State v. Sanford

203 La., 961,14 So. 2d 778 (1943).

3) The statute permits the indirect invasion of appel

lant’s right to the equal protection of the laws.

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 IT. S.

715 (1961); Herrington v. Plummer, 240 P. 2d 922

(5th Cir. 1956) cert, denied 353 IT. S. 924 (1957); City

of New Orleans v. Adams, 321 P. 2d 493 (5th Cir.

1963); City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 F. 2d 425,

(4th Cir., 1957) affirming 149 P. Supp. 562. (M. II

N. C., 1957); Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579

(N. D. Gfa., 1960); Turner v. City of Memphis, 369

IT. S. 350 (1962); Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U S

267 (1963).

3

Statement of the Case

On July 22, 1963 (E. 12) around 3:00 p.m. (E. 13), two

Negro women (E. 12-13), appellant and another (E. 13-14),

entered the coffee shop owned by the City-Parish, located

in the East Baton Eouge Parish Courthouse, also owned by

the City-Parish (E. 21, 22, 70). They had come to the

court house in order to attend a trial (E. 79). They pur

chased a candy bar at the counter and sat down at one of

the tables (E. 77), the normal procedure being to purchase

food at the counter and to carry it to the tables (E. 48).

The coffee shop provides no table service (E. 47-48).

The manager of the coffee shop, who operates the estab

lishment rent-free as part of the Vocational Training and

Eehabilitation Program provided for the blind by the State

of Louisiana (E. 70), upon learning of their presence, im

mediately suspended operations (E. 46). The white cus

tomers left and gathered in the hall outside the room. The

manager then asked appellant and her companion to leave

(E. 51). At the trial, he testified that Negroes were per

mitted to buy items at the counter (E. 46), but that they

were not allowed to sit at the coffee shop tables (E. 71).

When appellant and her companion refused to leave the

coffee shop, he summoned two deputies who arrested ap

pellant when she did not leave at their request (E. 72). At

the trial, respondent maintained that by sitting at the table

and refusing to leave, appellant was “ egging something on”

(E. 24), and that her behavior was a “ calculated sit-in for

the purpose of disrupting my business.” (E. 56).

With one exception, the testimony of respondent and

petitioner is without conflict.1

1 Appellant testified that a candy bar was purchased at the

counter. Respondent’s manager, who is blind (R. 69), testified

that it was a newspaper (R. 39, 62).

4

Respondent admitted that appellant did nothing to at

tract the attention of the crowd in the hall other than sit at

the table in the coffee shop (R. 42).

Appellant was charged with disturbing the peace, (LSA

RS 14:103.1) (as amended), tried, convicted and sentenced

to 30 days in jail.

Appellant’s motion for a new trial was denied (R. 19).

Appellant now applies to the Supreme Court of Louisiana

for Writs of Certiorari, Mandamus and Prohibition.

Specification of Errors

The trial court erred in convicting appellant in that;

1) The crime charged was not established by the evidence;

2) The statute under which the crime was charged is vague

and overbroad;

3) Appellant wTas excluded from a county court house on

the basis of race;

all in violation of appellant’s 14th Amendment right to due

process of law and the equal protection of the laws.

5

A R G U M E N T

The Arrest and Conviction o f Appellant for Disturb

ing the Peace Violated Her 14th Amendment Constitu

tional Rights in that:

1) There Was No Evidence of Her Commission of the Crime

Charged, in Violation of Due Process of Law.

The Statute under which appellant was convicted provides:

A. Whoever with intent to provoke a breach of the

peace, or under circumstances that a breach of the

peace may be occasioned thereby: . . . .

(4) refuses to leave the premises of another when

requested to do so by any owner, lessee, or any

employee thereof, shall be guilty of disturbing

the peace. LSA-RS 14:103.1 as amended.

The behavior which formed the basis for petitioner’s in

dictment and conviction consisted of her sitting at the table

in the courthouse coffee shop. Her refusal to leave was

founded upon her belief in her right to sit in a coffee shop

owned by the county and operated in conformity with a

state program. There is no evidence, therefore, that ap

pellant s refusal to leave was made with “ intent to provoke

a breach of the peace, or under circumstances that a breach

of the peace may he occasioned thereby.” The exercise of a

legal right, constitutionally protected, hardly qualifies as

such a “ circumstance.”

In Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 (1960), the Su

preme Court enunciated the constitutional requirement that

the evidence prove the crime charged. The court concluded

at p. 204:

6

Under the words of the ordinance itself, if the evidence

fails to prove all three elements of this loitering

charge, the conviction is not supported by evidence, in

which event it does not comport with due process of

law.

The facts of the instant case are closely similar to those

of Garner, et al. v. Slate of Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157 (1961)

where the Supreme Court of the United States reversed

state convictions of peaceful sit-in demonstrators under a

statute which defined disturbing the peace as the commis

sion of any act in such a manner as to unreasonably disturb

or alarm the public, holding at p. 162:

The convictions in these cases are so totally devoid of

evidentiary support as to render them unconstitutional

under the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The principle of Garner has been cited and followed in

recent cases. Reversing the state court conviction of Ne

groes who attempted to enter a waiting room customarily <

reserved for whites, the court held in Taylor v. Louisiana,

370 U. S. 154 (1962) per curiam, at p. 156, that there was

no evidence of a breach of the peace as charged:

Here as in Garner . . . , the only evidence to support the

charge was that petitioners were violating a custom

that segregated people in waiting rooms according to

their race, a practice not allowed in interstate trans

portation facilities by reason of federal law.

More recently, in Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229

(1963), where Negro demonstrators were again convicted

of the crime of breach of the peace, the Supreme Court re

versed: (p. 237).

7

. . . [T]hey were convicted upon evidence which showed

no more than that the opinions which they were peace

ably expressing were sufficiently opposed to the views

of the majority of the community to attract a crowd

and necessitate police protection.

The Fourteenth Amendment does not permit a State

to make criminal the peaceful expression of unpopular

views.

2) The Broadness and Vagueness of the ,Statute Effectively

Prohibits Constitutionally Protected Rights in Violation

of Due Process of Law.

The undisputed facts of this case reveal that the reason

appellant was requested to leave was because she is a Negro

and therefore not allowed to sit at the coffee shop tables.

The “ circumstances” under which the “breach of the peace

[was] occasioned” were created by respondent when its

agent closed the coffee house at the arrival of appellant, a

signal to the white patrons to congregate in the hall until

the “disturbance” was eliminated. The statutory language

intent to provoke a breach the peace or under circum

stances that a breach of the peace may be occasioned

thereby” is thus sufficiently vague and broad to effectively

proscribe appellant’s constitutional right to service in a

court house restaurant, when any disturbance, however

precipitated, occurs.

Appellant’s right not to be excluded from the court house

coffee shop on the basis of race is a federal constitutional

interest of very high rank. Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S.

284 (1963). As with freedom of speech, a high standard of

clarity is imposed on statutes employed to diminish racial

equality. It can hardly be maintained that the exercise of a

right judicially determined to belong to the appellant is

sufficiently announced as criminal by the terms of this

statute. Lametta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 (1939).

To the extent that appellant’s act is construed as a pro

test against a continuing practice of segregation in the face

of a constitutional requirement not to exclude upon the

basis of race, the state’s proscription of her conduct by

means of this statute violates constitutionally protected

speech. Here again the danger of the statute, is that its

language is vague enough, its terms broad enough to ob

scure an unconstitutional purpose and “ make criminal the

peaceful expressions of unpopular views”—Edwards v.

South Carolina, supra.

The fact that there may be circumstances under wThich a

refusal to leave will constitute a breach of the peace does

not mitigate the evil of a statute which is broad enough to

burden and inhibit constitutionally protected activity. The

danger of a statute wide enough to afford the semblance of

legality to state court prosecutions in the absence of sub

stantial evidence was outlined in Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U. S. 88, 97-98 (1940):

The existence of such a statute, which readily lends it

self to harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local

prosecuting officials, against particular groups deemed

to merit their displeasure, results in a continuous and

pervasive restraint on all freedom of discussion that

might reasonably be regarded as within its purview.

The Supreme Court of Louisiana has also spoken out

against such overbroad statutes as repugnant to its own

constitution. In State v. Sanford, 203 La., 961, 14 So. 2d

778 (1943), where an attempt was made to punish peaceful,

non-aggressive solicitation as activity “ calculated to dis

turb or alarm the inhabitants thereof, or persons present,”

the court, after noting the statute’s unconstitutionality un

der federal authorities, continued (14 So. 2d at 781):

9

Furthermore, to construe and apply the statute in the

way the district judge did would seriously involve its

validity under our State Constitution, because it is

well-settled that no act or conduct, however reprehensi

ble, is a crime unless it is defined and made a crime

clearly and unmistakably by statute.

3 ) The Statute Permits the Indirect Invasion of Appellant’s

Right to the Equal Protection of the Laws.

Because the state is constitutionally unable to prosecute

appellant under a statute making her unable to receive ser

vice at a coffee house owned by the City-Parish or to pro

test the refusal of such service, it has resorted to this

indirect route. Under Burton v. Wilmington Barking Au

thority, 365 U. S. 715 (1961), the Supreme Court decided

that when a state leases property to a restaurateur in an

automobile parking building owned and operated by an

agency created by the State, the equal protection proscrip

tions of the Fourteenth Amendment must be complied with

by the lessee. In the instant case, the connection between

the coffee shop and the state is more complete. The man

ager of the coffee shop was not an independent lessee as

was the case in Burton. Here, not only is the coffee shop

part of a publicly owned building, it is operated rent-free

as part of a state rehabilitation program.

Even before Burton, the 5th Circuit determined in Der-

rington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922 (5th Cir. 1956) cert,

denied 353 U. S. 924 (1957) that where the county leased

the cafeteria in a newly constructed court house to a private

tenant, the tenant’s refusal to serve Negroes on the basis of

race constituted state action in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution. More recently,

in City of Neiv Orleans v. Adams, 321 F. 2d 493 (5th Cir.

1963) the court found Burton controlling where the city had

10

leased the restaurant facilities in the New Orleans airport

to a private corporation.2

That the state cannot accomplish indirectly what it can

not constitutionally do directly was decided in Lombard v.

Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 267 (1963). In that case, three Negroes

and one white college student were convicted in a Louisiana

state court under a statute which specifically prohibited re

maining in a restaurant after the person in charge of such

business had ordered them to leave. Reversing the affirm

ance of the Supreme Court of Louisiana, the United States

Supreme Court observed: (p. 273):

. . . [T]he State cannot achieve the same result by an

official command which has at least as much coercive

effect as an ordinance. The official command here was

to direct continuance of segregated service in restau

rants, and to prohibit any conduct directed toward its

discontinuance; it was not restricted solely to preserve

the public peace in a non-discriminatory fashion . . . .

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, was intended,

in part, to expressly preclude this kind of indirect subver

sion of federally protected rights. An independent part of

Title II, Section 201(b), extends coverage to a restaurant

if the “ discrimination or segregation by it is supported by

State action.” This section is defined by §201 (d), 78 Stat.

243:

Discrimination or segregation by an establishment is

supported by State action within the meaning of this

title if such discrimination or segregation (1) is car

ried on under color of any law, statute, ordinance, or

2 See also City of Greensboro v. Simkins, 246 P. 2d 425 ('4th Cir.

1957) affirming 149 P. Supp. 562 (M. D. N. C. 1957) ; Coke v. City

of Atlanta, 184 P. Supp. 579 (N. D. Ga. 1960) : Turner v. City of

Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 (1962).

11

regulation; or (2) is carried on under color of any cus

tom or usage required or enforced by officials of the

State or political subdivision thereof,; or (3) is re

quired by action of the State or political subdivision

thereof.

Under the facts of this case, the arrest, conviction, and

sentencing of appellant meet the terms of the act under (2)

and (3) in that the segregation, was “ under color” of a

custom enforced by a political, subdivision of the state

(R. 21, 22, 70) and was itself the action of a political sub

division of the State, the manager of the coffee shop being

effectively within the employment and control of the state.

(R. 70).

Thus had the alleged offense occurred after the passage

of the Civil Rights .Act, it would have furnished a complete

statutory defense. §203, 78 Stat. 244 specifically provides

that:

No person shall . . . (c) punish or attempt to punish

any person for exercising or attempting to exercise any

right or privilege secured by section 201 or 202.

Senator Humphrey, floor manager of the Senate, read into

the record a Justice Department statement explaining

§203( c ) :

“ This [§203(c)] plainly means that defendant in a

criminal trespass, breach of the peace, or other similar

case can assert the rights created by 201 and 202 and

that State courts must entertain defenses grounded

upon these provisions.” 110 Cong. Record 9463 (daily

ed. May 1,1964) (emphasis supplied).

Federal authority has thus specifically removed the “ of

fense” charged from the state’s category of punishable

12

crimes, restating the existing judicially developed law to

eliminate any residual uncertainties. In the context of the

instant case, the Act secures and restates the existing fed

eral law. In any event the cause must be decided on the

basis of the law now existing. Thus even assuming,

arguendo, that Mrs. George’s conduct was not lawful

when it occurred it is certainly protected now by the Civil

Eights Act of 1964 and the proceedings against her must

abate. United States v. Chambers, 291 U. S. 217 (1934);

United States v. Tynen, 78 U. S. (11 Wall.) 88 (1871); cf.

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U. S. 226 (1964).

Eespectfully submitted,

J o h n n ie A. J ones

Attorney for Relator

530 South 13th Street

Baton Eouge, Louisiana 70802

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Of Counsel

13

Certificate

I, the undersigned, do hereby certify that I have served

copies of the foregoing on the Honorable Jack Gremillion,

Attorney General of the State of Louisiana, the Honorable

Sargent Pitcher, Jr., District Attorney for the Parish of

Bast Baton Eouge, and on the Honorable Judge C. A.

Barnett, by mailing a copy of same to each of them, postage

prepaid.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this ------ day of November,

1964.

J o hn n ie A. J ones

38