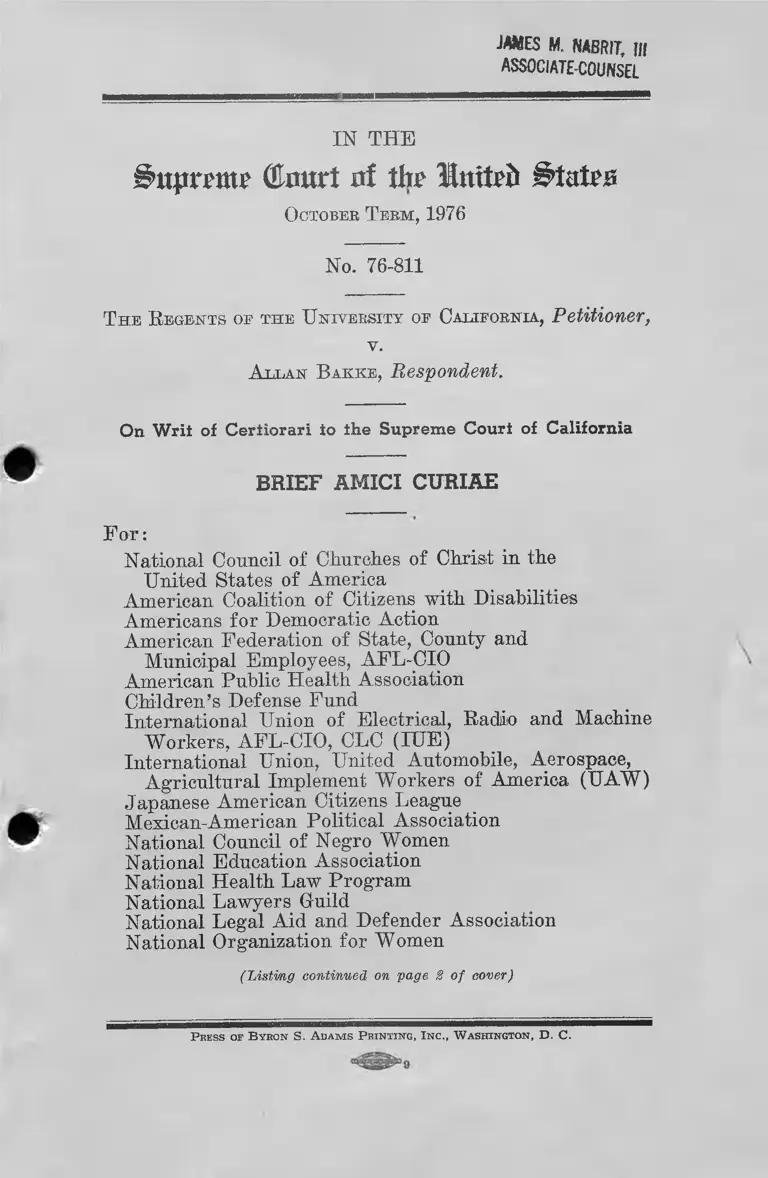

Bakke v. Regents Brief Amici Curiae for the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America and Others

Public Court Documents

June 7, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief Amici Curiae for the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America and Others, 1977. d88eb83b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6858182-44d0-4b82-b02f-36a918543dab/bakke-v-regents-brief-amici-curiae-for-the-national-council-of-churches-of-christ-in-the-united-states-of-america-and-others. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NABR1T, III

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

IN THE

Supreme Court of ttrr United #tateR

O ctober T e r m , 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R eg en ts oe t h e U n iv ersity oe C alifo rn ia , Petitioner,

v.

A lla n B a k k e , Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari io ihe Supreme Court of California

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

F o r:

National Council of Churches of Christ in the

United States of America

American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

Americans for Democratic Action

American Federation of State, County and

Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO

American Public Health Association

Children’s Defense Fund

International Union of Electrical, Radio and Machine

Workers, AFL-CIO, CLC (IUE)

International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace,

Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW)

Japanese American Citizens League

Mexican-American Political Association

National Council of Negro Women

National Education Association

National Health Law Program

National Lawyers Guild

National Legal Aid and Defender Association

National Organization for Women

(Listing continued on page 2 o f cover)

P ress of B yro n S. A d a m s P r in t in g , I n c ., W a sh in g to n , D. C.

National Urban League

United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO

United Mine Workers of America

United States National Student Association

Young Woman’s Christian Association

R ichard B . S obol

Sobol & Trister

910 Seventeenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

(202) 223-5022

„ , Attorney for AmiciOf Counsel:

M arian W r ig h t E delm an

S t e p h e n P. B erzon

1520 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

J o se ph L. R atjh, J r .

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

Dated; June 7, 1977

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I n ter est of A m ic i .......................................................................... 2

Co n sen t of t h e P a r t i e s ................ 2

Q u estio n P resented ....................... 2

S ta tem en t .................................................................... 3

Arg u m e n t :

I. Programs to Include Minorities in Public Pro

fessional Schools Are Not “ Suspect” or “ Pre

sumptively Unconstitutional” ................... 7

II. The University’s Special Admissions Program

Meets Even the Strictest Standard of Review . . 10

III. There Are No Realistic Alternatives to a Race

Conscious Special Admissions Policy as a Means

of Including Minorities in the Davis Medical

School .............................................................. 18

C on clu sio n ........................................................................... 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases :

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) .................... 8

Associated General Contractors v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d

9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974)

1 5 ,1 6

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) ....................... 8

Califano v. Goldfarb, 97 S.Gt, 1021 (1977) ..................9,17

Contractors Association v. Schulz, 442 F .2 d 159 (3d

Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ............... 15

Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.'S. 677 (1973) .......... . 9

Jackson v. Pasadena School District, 59 Cal. 2d 876,

31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 P .2 d 878 (1963) ..................... 16

11 Table of Authorities Continued

Page

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School District, 339

F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal. 1971), rev’d in part on

other grounds, 500 F.2d 349 (9th Cir. 1975) ......... 16

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 XJ.S. 351 (1974) ........................... 17

Koremat.su v. Morgan, 384 XJ.S. 641 (1966) .............. . 8

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ............................ 15

Lochner v. New York, 198 XJ.S. 4 5 ............................. 7

Loving v. Virginia, 388 XJ.S. 1 (1967) ................... 8

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 XJ.S. 184 (1964) ................ 8

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 XJ.S. 39 (1971) .................. .9,15

Morton y, Mancari, 417 XJ.S. 535 (1974) ........... . .10,15

Otero y . New York Housing Authority, 484 F.2d 1122

(2d Cir. 1973) ....................................................... 14

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez, 411 XJ.S. 1

(1973) ................................................. . . . 8 , 9

Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 XJ.S. 498 (1975) ............ 17

Soria v. Oxnard School District, 386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D.

Cal. 1974) ................ 16

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1974) (denial of modifica

tion of decree) aff’d, 519 F,2d 430 (9th Cir. 1975),

rev’d on other grounds, 427 U.S. 424 (1976) . . . . 16

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............ ‘......... ......................... 9,17

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 97 S.Ot. 996

(1977) .......................................... ...................9-10,15

United States y. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ............ ........... .............9,15

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ................. 9

Table of Authorities Continued

Page

S t a t u t e s :

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (6) .................................................. 17

C ongressional M aterial :

HR. Rep. No. 94-1558, pp. 2-3 (94th Cong., 2d Sess.)

(1976) ................................................................... 18

M iscella n eo u s :

Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical

School Admissions Requirements, U. S. A. and

Canada, Ch. 6 (Wash., I>. C. 1975) ....................... 11

Best, et ah, “ Multivariate Predictors in Selecting

Medical Studies,” 46 Journal of Medical Educa

tion 42-50 (1971) .................................................... 4

Conger and Fitz, “ Prediction of Success in Medical

School,” 38 Journal of Medical Education 947-47

(Nov. 1963).......................................... 4

Parity, “ Crucial Health and Social Problems in the

Black Community,” Journal of Black Health Per

spectives, June/July, 1974 34 ..............................12,13

A. C. Epps, “ The Howard-Tulane Challenge: A Medi

cal Education Reinforcement and Enrichment Pro

gram, ” 64 Journal of the National Medical Asso

ciation 317-24, 330 (July 1972) ........................... 5

Erdman, ‘ ‘ Separating the Wheat from Chaff: Revision

of MCAT,” 47 Journal of Medical Education, 747-

49 (1972)................................................................ 4

Hentoff, The New Equality (1984) ................................ 3

Health Policy Advisory Center, “ Your Health Care

Crisis,” (New York: Health/PAC 1972) ............ 13

Jackson, “ The Effectiveness of a Special Program for

Minority Croup Students,” 47 Journal of Medi

cal Education 620-24 (Aug. 1972) ............................ 14

Johnson, “ Highlights of Medical Alumni Survey,”

Howard University Medical Alumni Association 4

(Feb. 1977) ..................................................... ....13-14

IV Table of Authorities Continued

Page

Johnson, et ah, “ Recruitment and Progress of Minor

ity Medical School Entrants, 1970-74,” Journal of

Medical Education 721 (1975) .............................. 12

Johnson, et ah, “ Retention by Sex and Race of 1968-72

U.S. Medical School Entrants,” 50 Journal of

Medical Education 925 (1975) ..................... . 6

Kaleda & 'Craig, “ Minority Physician Practice Pat

terns and Access to Health Care Services,” 2

Looking Ahead 1 (Nov./Dec. 1976) ........................6,13

National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 1975, Na

tional Center for Health Statistics, Unpublished

Data, (U.S. Dept, of H.E.W. 1975) ....................... 14

P. B. Price, et al., “ Measurement of Physician Per

formance: Discussion,” 39 Journal of Medical

Education 203-11 (1964) ....................................... 5

Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971) .............................. 3

B. Roth, “ Patient Dumping,” Health/PAC Bulletin

# 58:6-10 (May/June 1974)............................ 13

Sandalon, Racial Preferences in Higher Education, 42

U. Chi. L. Rev. 653 (1972) ..................................... 7, 20

Simon, et al.,^“ Performance of Medical Students Ad

mitted Via Regular and Admissions-Variance

Routes,” 50 Journal of Medical Education 232

(1975) ................................................................... 5

A. R. Somers, “ Health Care in Transition; Direction

for the Future,” (Chicago : Hospital Research and

Educational Trust, 1971) .......................... 13

Spruce, “ Toward a Larger Representation of Minori

ties in Health Careers,” 64 of Nat’l. Med’l. Ass’n.

432 (1972).............................................................. 13

T. Thompson, “ Curbing the Black Physician Manp ower

Shortage,” 49 Journal of Medical Education 994

(Oot. 1974) ........................................................... H , l3

H. Til son, “ Stability of Employment in OEO Neigh

borhood Health Centers,” i 1 Medical Care No. 5

(1973) ......................... 13

Table of Authorities Continued v

Page

Turner, et ah, “ Predictors of Clinical Performance,”

49 Journal of Medical Education 338-42 (April,

1974) ..................................................................... 4

U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statis

tical Abstract of the United States, 1971............ 13

U. S. Dept, of Commerce and Labor, The Social and

Economic Status of Negroes in the United States,

1970, Special Studies, Bureau of the Census . . . . 12

U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1970

Census of Population, California, General Popula

tion, Characteristics, PC(1)-B6 (1971)................ 7

Weisman, et al. “ On Achieving Greater Uniformity in

Admissions Committee Decisions,” 47 Journal of

Medical Education 593-602 (1972) .......................

IN THE

Supreme ( to r t at % Ititiab States

O ctober T e e m , 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R eg en ts oe t h e U niv ersity of C alifornia , Petitioner,

v.

A llan B a k iie , Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

F or:

National Council of Cliurclies of Christ in the

United States of America

American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

Americans for Democratic Action

American Federation of State County and

Municipal Employees, AFL-CIO

American Public Health Association

Children’s Defense Fund

International Union of Electrical, Radio and Machine

Workers, AFL-CIO, CLC (IUE)

International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace,

Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW)

Japanese American Citizens League

Mexican-American Political Association

National Council of Negro Women

National Education Association

National Health Law Program

National Lawyers Guild

National Legal Aid and Defender Association

National Organization for Women

National Urban League

United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO

United Mine Workers of America

United States National Student Association

Young Woman’s Christian Association

2

INTEREST OF AMICI

Amici are a coalition of national organizations com

mitted to assuring that members of disadvantaged min

ority groups enjoy the full benefits of American life,

including adequate health care. Amici include relig

ious, professional, labor, health and public service or

ganizations, as well as groups devoted to the rights of

children, women and the handicapped. A description

of each of the amici is set forth in the Appendix. Amici

believe that the decision of the California Supreme

Court in this ease, if affirmed, would constitute a serious

setback to this nation’s efforts to include minority group

members among those who receive a professional edu

cation, and to increase thereby the availability of des-

parately needed services in minority communities.1

CONSENT OF THE PARTIES

This brief amici curiae in support of the petitioner is

filed with the consent of both parties.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Where color-blind academic admissions standards

result in the near total exclusion of minority appli

cants from a public medical school, does the Fourteenth

Amendment forbid the school from taking race into

account so as to include minorities in its student body ?

1 Several of the amici joined in a brief amici curiae in opposition

to the grant of certiorari in this case. The brief argued that, for

various procedural reasons, the merits of this case should not be

decided in this Court. Those amici adhere to the position there

expressed. See also Supplemental Memorandum of Amici Curiae,

arguing that a recent amendment to the California Constitution

provided an adequate state ground for the decision helow, and

provided further reason for this Court to decline to consider the

federal constitutional issue presented. These arguments are also

addressed in the Brief Amicus Curiae of the National Conference

of Black Lawyers.

3

STATEMENT

The civil rights struggles of the sixties focussed

America’s consciousness on the severe deprivations that

resulted from centuries of discrimination and neglect.

As a Nation, we came to understand that the eradica

tion of the effects of discrimination required, not pass

ivity or neutrality, but a measure of “ distributive jus

tice”—positive steps to include minorities in the bene

fits of American life.2

P rio r to the adoption of the so-called special admis

sions programs, there were only token numbers of

minority students enrolled in most professional schools.

This situation paralleled the sparsity of professional

services in minority communities. The problem was not

the unavailability of minority college graduates quali

fied for professional study, but the nature of the pre

vailing admission process. Admissions to professional

schools were granted on a competitive basis, largely

by reference to the college grades and standardized

test scores of the respective applicants. In the 1960’s,

there was an enormous increase in the number of ap

plicants to professional schools in this country. As a

result of this increase, and not because of any policy

decisions by the schools, the grade and score levels of

those admitted also sharply increased. See Brief for

Sanford II. Radish, et ah, in Support of the Petition

for a W rit of Certiorari, at pp. 7-12. Although there

were available substantial numbers of minority candi

dates whose grades and scores would have entitled them

to admission a few years earlier, very few minority

candidates met the new standards that had developed

through the inexorable force of competition. This sit-

a See generally Hentoff, The New Equality (1964); Rawls,

A Theory of Justice (1971).

4

uation was undoubtedly attributable, at least in sub

stantial part, to racial discrimination in primary and

secondary public education. See note 20, infra.

In the late sixties and early seventies, most of the

major professional schools in the United States de

cided that it was in their interest and in the interest

of society at large to do something to include minorities

in their student bodies. Special programs were adopted

under which minorities are admitted who do not meet

the score and grade standards set by the performance of

the top group of applicants. I t would be erroneous,

however, to conclude that the minorities so admitted are

“ less qualified” than whites who are rejected. To do so

would assume that qualifications can be measured only

by reference to traditional numerical criteria. But these

criteria, at best, have only limited utility in predicting

academic performance and none in predicting profes

sional performance.3

8 The two primary criteria in medical school admissions are

Medical College Admission Test (MOAT) scores and grade point

average in college (GPA).

The MCAT examination was developed in 1946 by the Associa

tion of American Medical Colleges to help identify students who

would successfully complete medical school. I t does not purport

to predict which applicants would perform successfully as prac

ticing physicians. Brdman, “ Separating the Wheat from Chaff:

Revision of MCAT” , 47 Journal of Medical Education, 747-49,

(1972). In fact, studies have consistently shown that MCAT

scores correlate well only with performance in the first, year of

medical school and correlate insignificantly or not at all with

success in the remainder of medical school, and particularly in

clinical studies. See, Best, ct al., “ Multivariate Predictors in

Selecting Medical Studies ” , 46 Journal of Medical Education 42-50

(1971) ; Turner, et al., “ Predictors of Clinical Performance” , 49

Journal of Medical Education 338-42 (April, 1974) ; Conger and

Fitz, “ Prediction of Success in Medical School” , 38 Journal of

Medical Education 943-7 (Nov. 1963).

The MCAT examination is structured to measure specific factual

knowledge in science, verbal skills and general information. Fail-

Because of file exclusionary effect ion minorities of

the application of these academic criteria and because

ure of medical school applicants to score well reflects inadequate

prior education .and does not provide a measure of intellectual

potential. A.C. Epps, “ The Howard-Tulane Challenge: A Medical

Education Reinforcement and Enrichment Program” , 64 Journal

of the National Medical Association 317-24, 330 (July 1972).

Other studies have shown that, college grades also do not. serve

as a good indicator of success in clinical studies or of effective

performance in practice. See We ism an, et al. “ On Achieving

Greater Uniformity in Admissions Committee Decisions” , 47 Jour

nal of Medical Education 593-602 (1972) ; P.B. Price, el al. “ Mea

surement of Physician Performance: Discussion” 39 Journal of

Medical Education 203-11 (1964).

The following table shows the continual dissipation of the

differences in performance of special and regular admittees dur

ing the course of medical school.

A-C SC O R ES1 N B M E-P C LER KSH iP-

1 A V E R A G E O F 0-4 R A T IN G S A SSIG N ED TO UNDE R-GRACH >A TE

C O LLEG E M C A T SCORE AND GpA.

2 A V E R A G E OF TOTAL NATIONAL B O A RD SCO RES. P A R T I

3 C LE R K SH IP SCORE A V E R A G E S

Comparisons at admission and on preelinical and clinical

performance indicators

Simon, et al., “ Performance of Medical Students Admitted Via

Regular and Admissions-Variance Routes” , 50 Journal of Medical

Education 232, 240 (1975). The inutility of the traditional criteria

in predicting performance as a doctor, or even overall medical

school performance, severely undercuts any applicant’s claim of

entitlement, to admission on the basis of his “ qualifications” .

6

of their limited value, professional schools concluded

that the concept of equal protection required the de

velopment of modes of access that would dissipate in

some part the effects of past discrimination. To this

end, many professional schools opted to select qualified

minorities by reference to non-academic, as well as aca

demic, criteria that would more broadly reflect the abil

ity of minority applicants to learn and practice the

profession, and the likelihood that their admission

would contribute to the solution of the problems pre

sented by the relative unavailability of professional

services in minority communities. A recent study has

shown that ninety (90%) per cent of the minority stu

dents admitted to medical school despite their lower

academic scores have graduated. This is a higher suc

cess rate■ than that of white medical students during

the same period.* And minority graduates in substantial

numbers are practicing in a manner that provides

medical services to disadvantaged communities.5

In all instances to our knowledge, the admission of

minorities, pursuant to a special admissions procedure,

has still afforded whites the large preponderance of the

admissions places, and, indeed, more places than their

proportion of the population in the areas served by the

school.” Thus, programs to include minorities have

4 Johnson, ct at, “ Retention by Sex and Race of 1968-72 TJ.S.

Medical School Entrants,” 50 Journal of Medical Education 925

(1975).

5 See p. 13, n. 18, infra.

0 In 1975-76, eight (8%) per cent of the medical students in the

United States were black. Gliicano and Indian, as compared with a

sixteen (16%) per cent representation of these groups in the

population at large. Kalida & Craig, “ Minority Physician Prac

tice Patterns and Access to Health Care Services” , 2 Looking

Ahead 1 (Nov./Dec. 1976). In 1974, four Chicanes were admitted

7

been moderate and have resulted only in a marginal

limitation in the likelihood of the admission of a white

applicant.

Amici believe that the Fourteenth Amendment does

not prohibit the special admissions program at the

Davis Medical School. Just as the “ Fourteenth

Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer’s

Social Statics” , Lochner v. New York, 198 TJ.S. 45, 75

(Holmes, J., dissenting), it does not enact the values

of competitive selection. The requirements of equal

protection do not prohibit a state from considering the

needs of the society and the needs of minorities in dis

tributing the valuable resource of a professional edu

cation. See Sandalow, Racial Preferences in Higher

Education, 42 II. Chi. L. Rev. 653, 674, 692 (1975).

A R G U M E N T

I. PROGRAMS TO INCLUDE MINORITIES IN PUBLIC PRO

FESSIONAL SCHOOLS ARE NOT "SUSPECT" OR "PRE

SUMPTIVELY UNCONSTITUTIONAL".

The fundamental analytical error of the court be

low was its conclusion that the petitioner’s special ad

missions program created a “ suspect” classification,

subject to review under a “ strict scrutiny” standard.

Thus, the University’s voluntary efforts to further

racial equality were misjudged by standards developed

to protect disadvantaged minorities from majoritarian

to Davis Medical School under the Regular Admissions program

and thirteen Chicanos and blacks were admitted under the Special

Admissions program, Petition for Certiorari, p. 6, for a total of

17 out of 100 places. The Chicano and black population of Cali

fornia is approximately 22%. TJ.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau

of the Census, 1970 Census of Population, California, General

Population Characteristics, PC(1)-B6, p. 6-89 (1971).

8

governmental action that stigmatizes, separates, in

jures or discriminates against them on the basis of

race. See, e.g., Korematsu v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641

(1966); McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ;

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ; Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954); Anderson v. Martin, 375

U.S. 399 (1964).

Apart from the decision below, the strict scrutiny

doctrine has never been applied to thwart govern

mental efforts to redress deprivations suffered by min

orities. To the contrary, this Court’s decisions make

clear that a classification is “ suspect” only when it

disadvantages a class entitled to special protection un

der the Fourteenth Amendment. A classification de

signed to benefit a disadvantaged class in their efforts

to overcome the effects of past discrimination, and

which incidentally limits in a small way the benefits

available to everyone else, is not a “ suspect” classifi

cation and is not subject to “ strict scrutiny.”

For example, in San Antonio School District v. Rod

rigues, 411 U.S. 1 (1973), this Court held that popula

tion groups disadvantaged by a Texas school financing

scheme were not a “ suspect” class, entitled to review

under a strict scrutiny standard. The Court explained

that the class h ad :

. . . none of the traditional indicia of suspectness:

the class is not saddled with such disabilities or

subjected to such a history of purposeful unequal

treatment, or relegated to such a position of poli

tical powerlessness, as to command extraordinary

protection from the m ajoritarian political proc

ess.

9

111 U.S. at 28.7 See Califano v. Goldfarb, 97 S.Ct. 1021,

1032-33 (1977). (Stevens, J., concurring) ; Id. at 1036

(Rehnquist, J., dissenting). The class of white appli

cants for admission to the Davis Medical School also

have “ none of the traditional indicia of suspectness,”

and government action that indirectly limits their op

portunities by assuring the inclusion of minorities is

not presumptively unconstitutional.8

In several instances, this Court has upheld race con

scious measures designed to eradicate or redress dis-

crimination against protected minorities. E.g., United

States Y. Montgomery County Board of Education, 395

U.S. 225 (1969); Swann v. CJiarlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ; McDaniel v.

Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ; United Jewish Organiza-

7 This description, also applies to women. See Frontiero v.

Richardson, 411 U.S. 677, 685-86 (1973).

In Rodriguez, the Court also held that the right to a public school

education is not a "fundamental right”—another indicia of the

applicability of a strict scrutiny standard. If public school edu

cation is not a fundamental right, then, of course, a medical school

education is not a fundamental right.

8 This distinction in standards applicable to racial classifications

based on the purpose of the classification and the identity of the

beneficiaries is implicit in the decision of this Court last Term in

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburg v. Carey, 97 S. Ct.

996 (1977). There, the Court upheld, against a Fourteenth

Amendment challenge, legislative districting along racial lines de

signed to create substantial black majorities in several election

districts, at the expense of the voting strength of certain white

citizens. The Court reached this conclusion without denominating

the classification as "suspect” or invoicing the strict scrutiny

standard. While there was no opinion of the Court, opinions

reflecting the views of several members of the majority emphasized

the lack of racial animus, and, indeed, the benign purpose of the

legislation. See Id. at 1009-10 (White, J.), 1016-17 (Stewart, J .).

See also Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976).

10

Hons v. Carey, 97 S.Ct. 996 (1977). In Morton v. Man-

car i, 417 U.S. 535 (1974), this Court unanimously up

held, against an equal protection challenge, a statute

which requires the Bureau of Indian Affairs to give a

preference in hiring to Native Americans. These de

cisions are entirely inconsistent with, the notion that

racial classifications are “ suspect” or “ presumptively

unconstitutional,” where their purpose is to redress

disadvantage and discrimination. Rather, in that sit

uation, the normal presumption in favor of the con

stitutionality of state action should be applied.

II. THE UNIVERSITY'S SPECIAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM.

MEETS EVEN THE STRICTEST' STANDARD OF

REVIEW.

For the reasons stated, amici believe this Court

should explicitly reject the notion that governmental

efforts intended to assist minorities in achieving full

equality should be viewed as presumptively unconsti

tutional and tested under a compelling interest stan

dard. Nevertheless, the program in this case meets

even the strictest standard of review. The Davis Medi

cal School’s efforts to include minorities in its student

body is justified by a compelling social interest.

As a result of pervasive historic discrimination,

there is a vast underrepresentation of certain minor

ities among physicians in the United States today.

President Lyndon B. Johnson sounded the keynote for

affirmative action:

Consider this fact: Among white citizens one

American in 670 becomes a doctor, but among Ne

groes . . . it is one in 5,000. . . . That is just not

right. That is a tragedy. That is a complete, ab

solute indictment of our entire educational system

and I am going to say so here today.

11

We must recruit more talented Negro students

for the medical profession. We must assist more

institutions to educate more Negro doctors, Negro

dentists, Negro nurses, and Negro technicians.

Speech, National Medical Association (Houston, Texas

April 14,1968), quoted in 61 Journal of the N at’l Medi

cal Ass’n 82 (1969). In 1972, when 12% of all Ameri

cans were black, only 4,478 or 1.7% of the 320,903 active

physicians were black. There was one physician for

every 649 persons in the general population; but only

one black physician for every 4,298 blacks.9 The ratio

of black physicians to black population actually wors

ened between 1942 and 1972, because the increase in

the number of black physicians did not keep pace with

the increase in the black population.10

Before special admissions programs were inaugu

rated in medical schools throughout the United States,

minority enrollment promised no improvement in this

situation. In the 1969-70 academic year, there were a

total of 1,042 black students enrolled in medical schools

throughout the country, or 2.8% of total enrollment—

not significantly more than the black proportion of ac

tive physicians. There were then 18 Ameriean-Indians

in medical schools, .04% of total enrollment, and 92

Mexican-Americans, .2% of total enrollment.11

9 T. Thompson, “ Curbing the Black Physician Manpower Short

age,” 49 Journal of Medical Education 944 (Oct. 1974).

10 Id.

11 Association of American Medical Colleges, Medical School Ad

mission Requirements, IJ.S.A. and Canada, Oh. 6 (Wash. D.C.

1975).

12

As a result of special admissions programs, there

has been a substantial increase in minority enrollment,

but still far below the proportions of these groups in

the population at large. By the 1974-75 school year,

the percentage of black medical students rose to 6.3%,

of American-Indians to 0.3%, and of Mexican-Ameri

cans to 1.2%-,.12

The Davis Medical School opened in 1968. In that

year there were no black or Ghicano students in the

school. From 1970-1974, fifty-seven black and Ghicano

students were admitted under special admissions, but

only seven were admitted under the regular admissions

program. Petition for a W rit of Certiorari, pp. 5-6.

I t is thus clear that absent special admissions, there

would be only token black and Ghicano enrollment in

the medical school today.

There is a health care crisis in disadvantaged minor

ity commuunities in California and throughout the

United States. The infant mortality rate for black

babies in America is almost double that of whites, and,

in fact, approximates the rates in the developing coun

tries.18 The maternal mortality rate for blacks is three

times that for whites, and is on the rise.14 Minority

babies who survive birth are twice as likely as white

12 Id. See also, Johnson, et al., “ Recruitment and Progress of

Minority Medical School Entrants, 1970-74” , 50 Journal of Medical

Education 721 (1975).

18 Darity, “ Crucial Health and Social Problems in the Black

Community” , Journal of Black Health Perspectives, June/July,

1974 at 3h

14 U.S. Dept, of Commerce and Labor, The Social and Economic

Status of Negroes in the United States, 1970, Special Studies,

Bureau of the Census, at 98.

13

babies to die in infancy.15 White life expectancy is

substantially higher.16 The figures go on and on.17

Studies have established that minority professionals

tend, to a very substantial extent, to practice in minor

ity communities, and that they do so to a far greater

extent than do white doctors.18 And, of course, statisti-

15 Spruce, ‘ ‘ Toward a Larger Representation of Minorities in

Health Careers” , 64 J. N at’l Med’l Ass’n 432 (1972).

16 Darity, op. cit. supra. See TJ.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau

of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1971 at 53.

17 The critical shortage of doctors in ghetto communities exacer

bates the health problems of minorities. Par fewer doctors are

willing to work in inner city neighborhoods than in more affluent

areas. For example, in 1976, the physieian-to-patient ratio was

73 per 100,000 in Central Harlem, as compared to 222 per 100,000

in New York State as a whole. T. Thompson, “ Curbing the Black

Physician Manpower Shortage” , 49 Journal of Medical Education,

944-50 (Oct. 1974) ; See also, B. Roth, “ Patient Dumping”

Health/PAC Bulletin #5 8 : 6-10 (May/June 1974) ; Health Policy

Advisory Center, “ Your Health Care in Crisis” (New York:

Health/PAC 1972); A.R. Somers, “ Health Care in Transition;

Direction for the future” (Chicago: Hospital Research and Edu

cational Trust, 1971).

18 A study of the practice patterns of two graduating classes at

two predominately black medical colleges—Howard University

and Meharry Medical College (Nashville, Tennessee)—revealed

that 36% of all graduates accepted intern and resident positions

in governmental hospitals serving the poor, as compared with 13%

of all medical school graduates. Kaleda & Craig, “ Minority

Physician Practice Patterns and Access to Health Care Services” ,

2 Looking Ahead 1, 5 (Nov./Dec. 1976). See also H. Tilson,

“ Stability of Employment in CEO Neighborhood Health Centers,”

11 Medical Care No. 5 (1973). Kaleda & Craig also found that

a far higher proportion of the graduates of these schools than of

all medical colleges chose to locate in Central City communities

which have the largest concentrations of minority residents. Kaleda

& Craig, op. cit. supra, p. 4, Table 2. Another study found that

approximately two-thirds of the patient care of Howard Uni

versity graduates was provided to blacks. Johnson, “ Highlights

14

cal likelihood is enhanced by expressed intention. Every

single student admitted to Davis under the special ad

missions program expressed an intention to serve dis

advantaged communities upon graduation. C.T. 68:

14-16. Given the direct link between minority physi

cians and improved delivery of health care services in

minority communities, there is obviously a compelling

societal interest in programs to include minorities in

medical college.

There are other compelling reasons for special admis

sions at Davis.

First, there is the essential fairness, in a state with a

22% black and Ohieano population,19 to include minor

ity students in a publicly supported medical school.

Second, the admission of minorities diversifies the

student body and permits faculty and students alike to

derive the benefits of an integrated education, inclusive

of minority group students who have a special appre

ciation for the customs, habits and medical needs of

their own j)eople.

The purpose of racial integration is to benefit

the community as a whole, not- just certain of its

members.

Otero v. New York Housing Authority, 484 E.2d 1122,

1134 (2d Cir. 1973).

of Medical Alumni Survey,” Howard University Medical Alumni

Association 4 (Feb. 1977). See generally Jackson, “ The Effec

tiveness of a Special Program for Minority Group Students,” 47

Journal of Medical Education 620-24 (Aug. 1972). A recent TJ.S.

government study revealed that 87% of the medical visits of black

patients were to black doctors. National Ambulatory Medical Care

Survey, 1975, National Center for Health Statistics, Unpublished

Data, (II.S. Dept, of H.E.W., 1975). See also, Briefs Amici Curiae

of the Mexican-Ameriean Legal Defense Fund and the California

State Department of Health.

19 See note 6, supra.

15

Third, increased numbers of minority professionals

is a countervailing force to racial polarization, because

minority professionals are a source of leadership to

minority communities, and are able to assume positions

of importance and power in the society at large. More

over, to black and Chicano youths, professionals of

their own race, and functioning in their own commun

ities, serve as role models, and demonstrate the feasibil

ity of educational and professional advancement.

This Court has approved race conscious measures

designed to overcome the legacy of discrimination

against minorities.

The Board of Education, as part of its affirmative

duty to disestablish the dual school system, prop

erly took into account the race of elementary school

children in drawing attendance lines. To have

done otherwise would have severely hampered the

board’s ability to deal effectively with the task at

hand.

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 TLS. 39, 41 (1971). See

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ; Morton v. Mancari, supra;

United Jewish Organization v. Carey, supra. Cf. Lau

v. Nichols, 414 TT.;S. 563 (1974). And the lower courts

have upheld race conscious hiring programs adopted

pursuant to the Affirmative Action requirements of

Executive Order 11246. Associated General Contrac

tors v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Car. 1973), cert, de

nied, 416 TLS. 957 (1974); Contractors Association v.

Schulz, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir.), cert, denied, 404 TLS.

854 (1971).

[Colorblindness] has come to represent a long

term goal. I t is by now well understood, however,

that our society cannot be completely colorblind in

16

tilie short term if we are to have a colorblind soci

ety in the long term

Associated General Contractors v. Altshuler, supra,

490 F.2d at 16.

The Court below suggested that race conscious meas

ures are not permissible unless there has been a history

of past discrimination and unless the remedy is imposed

by the Courts after a finding of unlawful conduct. 553

Pae.2d at 1168-69. But reason does not support such a

rule and there are strong reasons to the contrary.

I t may be that in this case the Davis Medical School

did not itself practice racial discrimination prior to

the adoption of its special admissions program, but the

Medical School is an agency of the State of 'California.

And, as the briefs amicus curiae of the NAA.GP Legal

Defense Fund and the Bar Association of San F ran

cisco County, et al. make clear, there has been substan

tial racial discrimination against minorities in Califor

nia in connection with elementary and secondary edu

cation.*0 In cannot reasonably be doubted that the

relative absence of minorities in the Davis student

body prior to the adoption of the special admissions

program was a result of this discrimination. In these

circumstances, the Fourteenth Amendment gives wide

20 State and federal courts in California have found racial segre

gation and discrimination in the schools of the state’s largest cities.

See e.g., Johnson v. San Francisco Unified, School District, 339

F. Supp. 1315 (N.D. Cal. 1971), rov'd in part on other grounds,

500 P. 2d 349 (9th Cir. 1974) ; Spangler v. Pasadena City Board

of Education, 311 P. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1974) (denial of modi

fication of decree) aff’d, 519 F. 2d 430 (9th Cir. 1975), rev’d on

other grounds, 427 U.S. 424 (1976) ; Soria v. Oxnard School Dis

trict, 386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974) (Los Angeles) ; Jackson

v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal. 2d 876, 31 Cal. Eptr. 606,

382 P.2d 878 (1963).

17

range to voluntary measures designed to include min

orities in the medical college.

School authorities are traditionally charged with

broad power to formulate and implement educa

tional policy and might well conclude, for example,

that in order to prepare students to live in a plur

alistic society each school should have a prescribed

ratio of Negro to white students reflecting the pro

portion of the district as a whole. To do this as an

educational policy is within the broad discretion

ary powers of school authorities; absent a finding

of constitutional violation, however, that would not

be within the authority of a federal court.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971).

There is no reason for prohibiting voluntary correc

tive steps until a lawsuit has been instituted, defended

and lost. This Court has recognized that the remedial

or benign purpose of disparate treatment supports a

finding of constitutionality, without reference to legal

liability for past discrimination. See Schlesinger v.

Ballard, 419 U.S. 498 (1975); Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351 (1974) ; Califano v. Goldfarb, 97 S.Gt. 1021,

1028, n. 8 (1977) (plurality opinion).

Moreover, our national efforts to eradicate racial

discrimination recognize the desirability of voluntary

corrective efforts. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(6).

Voluntary action comes about without the expense and

animosity of litigation and judicial findings of invid

ious discrimination. More importantly, a principle of

correction only through litigation imposes the burden

on disadvantaged minorities to marshall the resources

to institute and successfully prosecute what is often

18

very expensive, protracted and complicated litigation.

I t may seem that the federal courts are flooded with

lawsuits seeking to redress racial discrimination, but

the fact is that most valid claims are not litigated be

cause of these practical factors."1 Redress through

litigation also imposes a heavy burden on the courts

and on the defendants. A rule limiting affirmative

action to litigated cases and court imposed injunctions

would frustrate and not further the purposes of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Where a university determines voluntarily to redress

a near-total absence of minority group members from

its student body, its efforts should be welcomed and not

denied. Whites are accorded more places in the Davis

Medical School than their proportion of the California

population. Nothing in the constitution demands the

virtual exclusion of minorities in pursuit of a policy

of Social Darwinism.

HI. THERE ARE NO REALISTIC ALTERNATIVES TO A

RACE CONSCIOUS SPECIAL ADMISSIONS POLICY

AS A MEANS OF INCLUDING MINORITIES IN THE

DAVIS MEDICAL SCHOOL.

As discussed above, the court below applied the

1 ‘ strict scrutiny” equal protection test in this case.

Although that court was willing to assume that the

Davis special admissions policy is justified by a com

pelling state interest, 553 Pac. 2d at 1165, it invalidated

the policy on the ground that the state’s interest could

be served without resorting to race conscious admis

sions. Id. Because, under this Court’s decisions, the

strict scrutiny test should not be applied to a benign

21 See H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, pp. 2-3 (94th Cong., 2d Sess.)

(1976).

19

policy intended to help overcome the present effects

of past discrimination against minority groups, it is

not the University’s burden to establish that there are

no colorblind means of achieving the same purpose.

Where the strict scrutiny standard is not applicable,

it is not for the courts to weigh the desirability of

alternative policies that might have been adopted by

state officials. I f the policy adopted by the state is

justifiable, that is the end of the inquiry.

But apart from the invalidity of the inquiry into pos

sible alternatives, we think it clear that the alternative

policies suggested by the California Supreme Court

would each be ineffective or impractical. None is in

any sense supported by the record in this case or by

any empirical experience.

First, the lower Court suggested additional recruit

ment of minorities. Id. at 1166. The Medical School

already engages in intensive minority recruitment, and

there is simply no reason to believe, and indeed every

reason to doubt, that additional recruitment would pro

duce minority candidates who meet regular admissions

standards.

Next, the Calif ornia Court suggested that the size of

the school be expanded in the hope that a, larger enter

ing class would include a large number of minorities. Id.

But the expansion of medical school facilities is enorm

ously costly, and funds for this purpose have not been

made available. Moreover, given the more than 3,700

applications for the 100 spaces in the 1971 entering

class at Davis and the large number of white candi

dates with excellent credentials, it is doubtful that even

doubling of the size of the medical school would have

any significant impact on regular minority admissions.

Bather, it seems probable that the increase in regular

minority admissions would be proportionate to the in-

20

crease in the. size of the school, so that the size of the

school would have to be multiplied many times before

any substantial number of minority candidates would be

admitted by regular admissions. This is not a prac

tical approach.

The California Court placed most emphasis on a

policy of affording special consideration to economic

ally “ disadvantaged” applicants rather than to minor

ity applicants. Id. But many black applicants are not

“ disadvantaged” in terms of economic status, and most

economically disadvantaged applicants are white. See

Sandalow, op. cit. supra, at p. 692, n. 113. This ap

proach would cut off: the source of many of the most

qualified black applicants—those from middle class

families who are most likely to seek professional train

ing—and recpdre the admission of large numbers of

additional white applicants to achieve the goal of more

minority students. This approach would be awkward,

unmanageable and of dubious efficacy in achieving the

goal of increased numbers of minority professionals.

Lastly, the California Court suggested more flexible

admissions standards, which would emphasize personal

interviews, recommendations and other non-score data.

Id. But unless such a program is intended to provide a

mechanism for surreptitious consideration of race,

there is no reason to believe it would significantly in

crease the admission of minority candidates. There

are white as well as black candidates with impressive

non-score credentials, and many of the whites have

impressive score credentials as well. Given the great

preponderance of whites among the applicant pool, it

seems reasonable to conclude that a truly noil-racial

implementation of such a program would not signifi

cantly increase admissions of minority candidates.

21

We submit that Davis’ special admissions policy is

narrowly drawn, is fair to white applicants, and is ef

fective to achieve a compelling state purpose. I t should

not be discarded in favor of indirect procedures that

would radically alter the school or its regular admis

sions policy, and that are of questionable value in

increasing the admission of minority students.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the California Supreme Court

should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

R ichard B . S obol

Sobol & Trister

910 Seventeenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20006

(202) 223-5022

Attorney for Amici Curiae

Of Counsel:

M arian W r ig h t E delm a n

S t e p h e n P . B erzon

1520 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

J o seph L . R a ijh , J r .

1001 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D. C. 20036

D ated: June 7,1977

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

The National Council of Churches of Christ in the

United States of America is the cooperative agency of

30 national Protestant and Eastern-Orthodox religious

denominations with an aggregate membership of over 40

million people. The National Council of Churches of

Christ is organized exclusively for religious purposes and

it is committed to promoting the application of the law

of Christ in every sphere of human relations. In light of

the Council’s historic involvement in the struggle for

racial justice and its interest in promoting equal educa

tional opportunities for all, regardless of race, ethnic back

ground, sex, or economic condition, the National Council

of Churches of Christ has joined this brief.

The American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

(ACCD) is a nationwide organization composed of both

disabled and non-disabled individuals and of local, state and

national organizations dedicated to assisting disabled

people. ACCD works on behalf of its thousands of mem

bers to obtain improved education, expanded rehabilita

tion programs, accessible housing, effective transportation

and extensive employment opportunities and to end dis

crimination on the basis of disability.

The Americans for Democratic Action, founded in 1947,

is an organization of individuals that has devoted itself

to the cause of civil rights for all. Over the past three

decades, it has worked for the enactment of civil rights

legislation and for the promotion of equal opportunity

through every branch of government and in all walks of

life.

The American Federation of State, County and Mu

nicipal Employees, AFL-CIO, is the largest public sector

labor organization in the United States, with a member

ship of more than 750,000 persons, almost all of whom

are employed by state and local governments throughout

2a

the nation. AFSCME is deeply concerned with the

achievement of equality in America. Its members, as pub

lic employees and as citizens, are committed to the prin

ciple of affirmative action toward equal opportunity by

public institutions.

The American Public Health Association is a national

non-governmental organization established in 1872. Its

objective is to protect and promote personal and environ

mental health. With a membership of over 50,000 health

professionals, including 51 affiliated organizations, it is

the largest public health organization in the world.

APHA’s primary purpose is to develop a national health

policy to provide equitable, low-cost, quality health care

for all citizens. Since 1973, the Association has pursued

a policy of working with educational institutions to in

crease the number of minority health professionals by

developing and expanding affirmative action programs.

The principal aim of the Children’s Defense Fund of the

Washington Research Project is to assist in achieving

equality of opportunity for all citizens by public education,

monitoring of agency programs, negotiation and litigation.

Established in 1968, the Project is deeply concerned with

educational issues, particularly those dealing with allevi

ating the continuing effects of racial discrimination in pub

lic schools. The Project has conducted a number of studies

of federal desegregation policies and the impact of federal

aid to education. These studies include higher as well as

primary and secondary education to ensure that the na

tional commitment to end discrimination is fulfilled. In

1973, the Project complemented these efforts with a broader

focus on children’s rights, seeking systematic reforms on

behalf of all the nation’s children, with special attention to

the unique problems of minority and poor children.

The International Union of Electrical, Radio and Machine

Workers, AFL-CIO, CLC (IUE) has over 285,000 members

3a

throughout the Nation, 100,000 of whom are women, and

many of whom are members of disadvantaged minority

groups. The IUE is a leader among unions in championing

the civil rights of its members. It has instituted numerous

suits under federal and state fair employment laws, and has

fded many charges of discrimination with administrative

agencies. The IUE believes that affirmative action is an in

dispensable tool toward the elimination of the legacy of

discrimination.

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace,

Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW) is

the largest industrial union in the world, representing

approximately a million and a half workers and their

families. Including spouses and children, UAW repre

sents more than 4y2 million persons throughout the United

States and Canada. The UAW, which is deeply com

mitted to equal opportunity and anti-discrimination, does

much more than bargain for its members. It is active in

civic affairs and citizenship and legislative activities. It

is by mandate of its Constitution and tradition deeply in

volved in 'the larger issues of the quality of life and the

improvement of democratic institutions. The questions

presented by this case vitally affect the UAW and its

members.

The Japanese American Citizens League (JA.OL) is a

national organization comprised of 105 local chapters with

over 30,000 members in 32 states. Since its official organi

zation in 1930, JACL has been dedicated to the promotion

of the welfare of its members and to the broader goal of

the protection of the rights of all Americans. Having

suffered through one of the most intense periods of dis

crimination in the modern history of the United States—

the exclusion of over 100,000 persons of Japanese descent

from the West Coast during World War II—Japanese

Americans are acutely aware of the potentially invidious

and unjust consequences of governmental programs based

4a

exclusively upon race. However, JACL is joining in this

brief because it believes that it is imperative that affirma

tive efforts be made to increase educational opportunities

for individuals who are disadvantaged because of race.

Mexican-American Political Association (MAPA) is a

non-profit corporation, founded in 1960, for the purpose

of increasing Mexican-American participation in the

American political process. The organization concen

trates its energies on promoting legislation effecting Mex-

ican-Amricans such as voting rights, education and affirma

tive action. MAP A has chapters throughout California

and the southwest.

The National Council of Negro Women, founded in 1935,

is a coalition of twenty-seven national organizations. It

is committed to improving opportunities for black women

and their children. The issues in this case vitally concern

its constituent organizations and their members.

The National Education Association, founded in 1857 and

chartered by a special act of Congress in 1906, is the

nation’s oldest and largest organization of educators. I t ’s

current membership of 1,500,000 persons includes more

than 44,300 members employed in higher education. The

NEA believes that our nation’s educational institutions,

at all levels, should reflect the diversity of our society

and that the presence of significant numbers of minority

students in professional schools will have the salutary

effect of motivating minority students to aspire to pro

fessional careers and of promoting greater racial education,

and harmony.

The National Health Law Program is a legal service

corporation support program for the poor. Its functions

include litigation, legislative analysis, administrative en

forcement and. education of attorneys, health workers and

policy makers on behalf of low income health consumers.

Since its founding in 1970, a key component of its litigation

5a

effort has been to assure access to health care by minori

ties and the poor.

The National Lawyers Guild is an organization founded

in 1937 with over 5,000 members. It works to maintain

and protect civil rights and civil liberties.

The National Legal Aid and Defender Association

(NLADA) is the national organization of public defense

and legal services offices. Its constituency is the indigent

population served by attorneys from these offices. Founded

in 1911 by 15 legal aid societies, NLADA today has over

1,500 member programs with approximately 6,000 partici

pating attorneys, including, the great majority of defender

offices, coordinated assigned counsel systems, and legal

aid societies in the United States. NLADA seeks to enlist

the support of the bar and the general public on behalf

of equal access to legal representation.

The National Organization for Women (NOW") is a

national membership organization of women and men or

ganized to bring women into full and equal participation

in every aspect of American society. The organization

has a membership of approximately 56,000 with over seven

hundred chapters throughout the United States.

The National Urban League, Inc., is a charitable and

educational organization organized as a not-for-profit cor

poration. For more than 65 years the League and its

predecessors have addressed themselves to the problems

of disadvantaged minorities in the United States by im

proving the working conditions of blacks and other minori

ties, by fostering better race relations and increased un

derstanding among all persons, and by implementing pro

grams approved by the League’s interracial board of trus

tees. The League has concluded from its experience in

manpower training, placement of minority professionals

and other employment related programs that special meas

ures are required to overcome the damage done by long

term racism and prejudice.

6a

The United Farm Workers of America, AFLhCIO, is an

unincorporated association which functions as a trade union

on behalf of farm workers. In addition to its interest in

wages, hours, and working conditions, it is vitally inter

ested in the social betterment of its members and particu

larly in their obtaining higher educational opportunities.

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) is a

labor organization representing coal miners. Throughout

the United States the UMWA has been in the forefront

of the nation’s struggle for equal opportunity in employ

ment and it is dedicated to the principle of equal oppor

tunity in every walk of American life.

The United States National Student Association, founded

in 1946, represents Colleges, Universities, County and

Junior College Students throughout the Nation. Histori

cally, NSA has had a commitment to Civil Rights, includ

ing the right of access to quality education for racial and

ethnic minorities.

The Young Woman’s Christian Association (YWCA) is

the oldest and largest women’s membership movement in the

United States. It is a part of the world YWCA organiza

tion, which operates in 83 countries, and is dedicated to

helping women and girls put into practice the ideas of

peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all people. One of

the YWCA’s overriding priorities is the elimination of

racism.

% -****•

V * ’

IP

H.*

o •"*

K a i