Correspondence from Guinier to Heenan McGuan

Correspondence

September 9, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Hardbacks, Briefs, and Trial Transcript. Correspondence from Guinier to Heenan McGuan, 1985. fdd7ec7c-d692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a6a7596f-2a9a-4b7d-8660-ebe257c28256/correspondence-from-guinier-to-heenan-mcguan. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

bfeuse

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE ANO EDUCATIONAL FUNO' INC'

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 100'13o(212) 219-1900

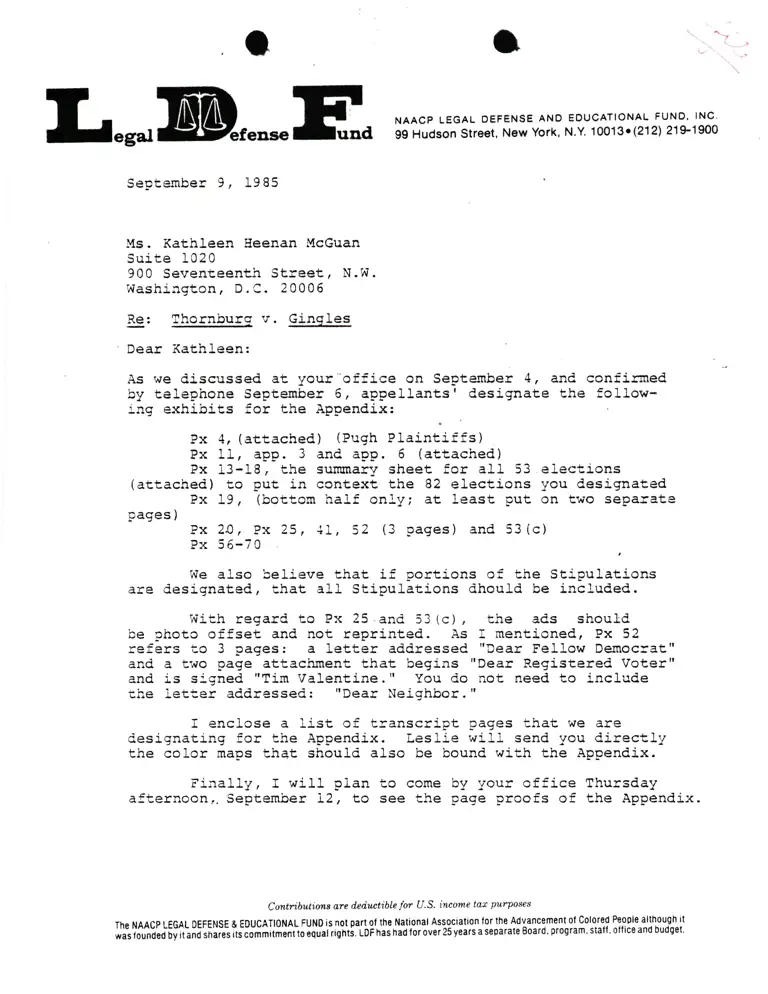

September 9, 1985

Ms. Kathleen Heenan McGuan

Suite 1020

900 Seventeenth Street, N.W.

Washiagton, D.C.20005

Re: Thornburq v. Ginqles

Dear Kathleen:

As we discussed at your"offj.ce on Septamber 4, and conflrmed

by telephone September 6 , aSlpellantsr desigrnate the follow-

ing exhibits for the Appendj.x

Px 4, (attached) (Pugh Plaintiffs)

Px 11, app. 3 and, app. 6 (attached)

Px i3-I8, the sumrnar:r sheet for all 53 electlons

(attached) to put in context the 82 elections you d,esignated

Px L9, (bottom half onJ.yr at least put on two separate

pages )

Px 20, Px 25, 41, 52 (3 pages) and 53(c)

Px 56-70

we also beU.eve that if portions of the Stipulations

are designated, that all- Stipulations dhould be included.

With regard to Px 25.and 53 (c) , the ads should

be photo offset and not reprinted. As I mentj.oned, Px 52

refers t,o 3 pages: a letter addressed "Dear Fellow Democrat"

and a two page attachment that begins "Dear Registered Voter"

and is srgned "Tim Valentine. " You do not need to include

che lett,er addressed: "Dear Neighbor."

I enclose a list of t,ranscript pages that we are

desi,gnating for the Appendix. Leslie will send you directly

the color maps that shoulo also be bound with the Appendix.

Final1y, I will plan to come by 1'our office Thursday

afternoonr. September L2, to see the page proofs of the Appendix.

Contributions are deduatible lot U.S. income tat purposes

rhe NAAcp LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIoNAL FUN0 is not part ol the National Association Jor the Advancement of c0lored People althouoh it

;;;i;;;;d btltino sr,.rer iis-io-mmiiidni to iqr1tiignti. ioi nas had tor over 25 years a s0parat0 Board. program, stair, or{ics and budset.

t'Is. Kathleen Heenan ltlcGuan -2- Septernber 9, 1985

fhank you for your cooPeration-

:7;'v' c

,&*, 'gLLttwYL\

r,aii Guinier

LG/ x

Encl.oEure

cc: LesU.e Winner, Eeq.