Clinton v. Jeffers Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

July 25, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clinton v. Jeffers Motion to Affirm, 1990. 3a37e9ce-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a78f5e2e-cf8a-4073-a156-4d77d6a3fd82/clinton-v-jeffers-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

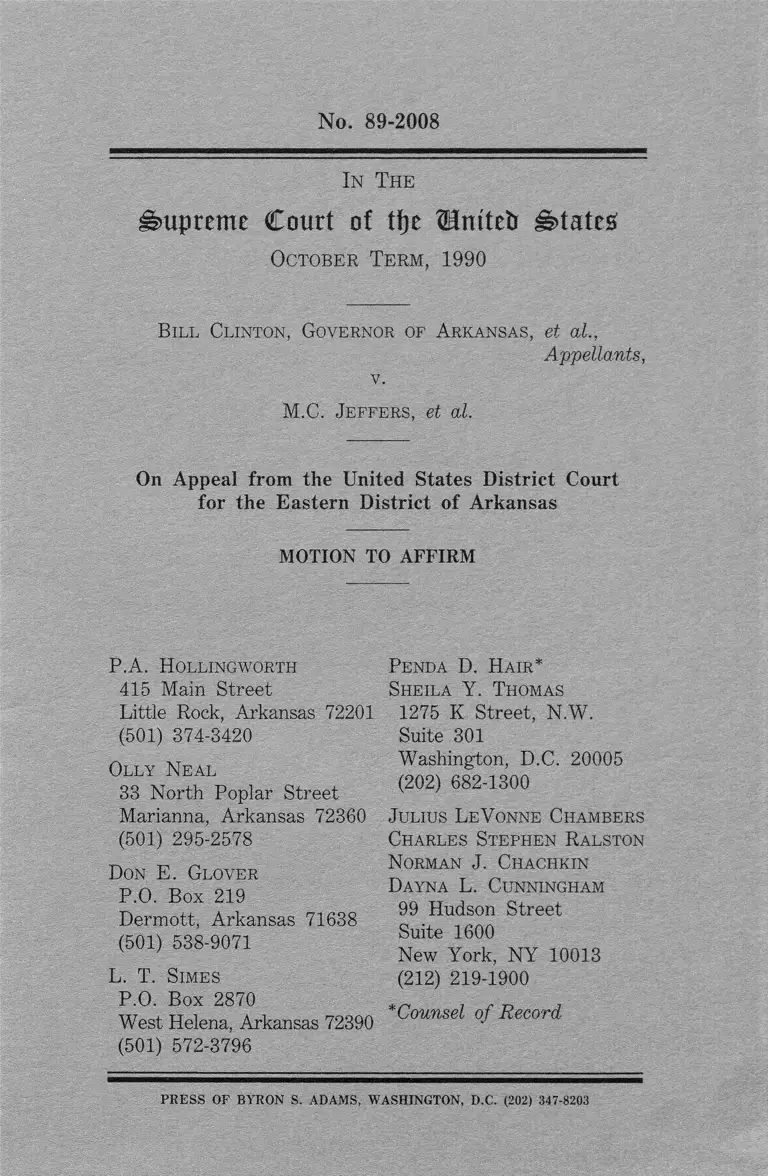

No. 89-2008

In The

Supreme Court of tfjc Mntteb states

October Term, 1990

Bill Clinton, Governor of Arkansas, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

M.C. Jeffers, et al.

On Appeal from the United States D istrict Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas

MOTION TO AFFIRM

P.A. Hollingworth

415 Main Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

(501) 374-3420

Olly Neal

33 North Poplar Street

Marianna, Arkansas 72360

(501) 295-2578

Don E. Glover

P.O. Box 219

Dermott, Arkansas 71638

(501) 538-9071

L. T. Simes

P.O. Box 2870

West Helena, Arkansas 72390

(501) 572-3796

Penda D. Hair*

Sheila Y. Thomas

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

Dayna L. Cunningham

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

*Counsel o f Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

QUESTION PRESENTED

The only question which properly arises on this

appeal is: did the court below err in applying well-settled

principles announced by this Court in Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U .S. 30 (1986), and other decisions to the

particular facts which it found, on the basis of

overwhelming evidence, to exist and to limit the

opportunities of black citizens to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives o f their choice in a

number o f Arkansas legislative districts under the State’s

1981 districting plan?

- 1 -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Question Presented .................. i

Table of Authorities ................ iii

Facts ........... 1

REASONS FOR SUMMARY AFFIRMANCE ...... 5

A. The Judgment Is Supported

by Unimpeachable Findings on

the Relevant Factors Identified

in Thornburg and a Fully Supported

Conclusion, Based on the Totality

of the Circumstances, that

Black Citizens' Opportunity to

Participate in the Political

Process and to Elect

Representatives of Their

Choice Was Limited and Denied

by the 1981 General Assembly

Districting P l a n ................. 7

B. The Legal Issues Sought to be

Raised by Appellants Do Not

Merit Plenary Review in

this Case ........................ 22

CONCLUSION ........................... 3 3

ii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S.

130 (1976) .................. 26

City of Richmond v. United States,

422 U.S. 358 (1975) 26

Costello v. United States, 365

U.S. 265 (1961) 28

Czaplicki v. The S.S. Hoegh

Silvercloud, 351 U.S. 525

(1956) 28

Gardner v. Panama Railroad Company,

342 U.S. 29 (1951) 28

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp.

345 (1984), aff'd, 478 U.S. 30

(1986) ...................... 10, 23

Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398

(7th Cir. 1984), cert, denied,

471 U.S. 1135 (1985) 23

Lewellen v. Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229

(E.D. Ark. 1986), aff'd, 843 F.2d

1103, opinion modified, 851 F.2d

1108 (8th Cir. 1988), cert, denied,

109 S. Ct. 1171 (1989) ..... 15

Major v. Treen, 574 F. Supp. 325

(E.D. La. 1983) ............. 23

Mississippi Republican Executive

Committee v. Brooks, 469 U.S.

1002 (1984), aff'g Jordan v.

Winter, 604 F. Supp. 807 (N.D.

Miss. 1984) ................. 6, 23

iii

CASES (Continued) PAGE

Neil v. Coleburn, 689 F. Supp.

1426 (E.D. Va. 1988) ....... 23

Smith v. Clinton, 687 F. Supp. 1310

(E.D. Ark.), aff'd, 109 S. Ct.

548 (1988) .................3, 5, 6, 18

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.

30 (1986) ................... passim

United Jewish Organizations v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) .. 25

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755

(1973) ...................... 26

STATUTES

Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 1973 et seq.... passim

MISCELLANEOUS

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1982) 27

Motion to Dismiss or Affirm,

Mississippi Republican

Executive Committee v. Brooks,

No. 83-1722 ................. 6

Petition for Certiorari, City of

Norfolk V. Collins, No. 89-989 5

Petition for Certiorari, Sanchez

V. Bond, No. 89-353 ...... 5

Sup. Ct. Rule 18.6 ............ 1

i v -

In the

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1990

No. 89-2008

BILL CLINTON, GOVERNOR OF ARKANSAS, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

M.C. JEFFERS, et al.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District o f Arkansas

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Appellees move pursuant to Sup. Ct. Rule 18.6 to

affirm the judgment below on the ground that the questions

presented in the Jurisdictional Statement are so insubstantial

on this record as not to require further argument.

Facts

Following the 1980 Census, new districts for the

Arkansas General Assembly were drawn in 1981 by the

State Board o f Apportionment (then Governor Frank White,

Attorney General Steve Clark and Secretary o f State Paul

Riviere). Both House and Senate districts crossed political

subdivision boundaries.1 Although black citizens

constituted 16% of Arkansas’ voting-age population (VAP),

and were highly concentrated in the eastern and southern

parts o f the State,2 the 1981 districting plan resulted in

‘The 1981 House districting plan split 46 counties, ten

townships and at least three municipalities among two or

more districts, while the 1981 Senate plan split 27 counties,

seven townships and at least two municipalities. PX 15.

Several counties were carved up into four or five pieces,

each o f which formed a part o f a separate district. Id. At

least one city, Pine Bluff, was split to protect a white

incumbent even though this configuration was not required

to satisfy the one-person, one-vote principle. J.S. App. 34.

One eastern Arkansas district included territory on both

sides of the Arkansas River (with no bridge), forcing

"citizens north o f the river to drive more than 90 miles to

reach the largest city in their district, where their state

representative lives," J.S. App. 35.

2Since Reconstruction, no black has been elected to the

General Assembly from eastern Arkansas, and only one

district in southern Arkansas (majority-black) has elected a

black representative.

- 2 -

legislative districts with a majority-black VAP only in

Little Rock (in the center o f the State) and Pine Bluff.3

Appellees brought this suit challenging the 1981

legislative district lines in these areas o f the State4 as

violative o f § 2 o f the Voting Rights Act.5 Following a

twelve-day trial, the District Court made extensive findings

3Of the total 35 Senate and 100 House districts, one

Senate district and a three-seat House district in Little

Rock, and one House district in Pine Bluff, had majority-

black VAPs.

4A s to Little Rock, appellees claimed that four single-

member, majority-black VAP House districts could have

been drawn in place o f the three-member district. The

remaining claims concerned single-member districts in

eastern and southern Arkansas. (A multi-member House

district in eastern Arkansas had previously been invalidated

under § 2 o f the Voting Rights Act, Smith v. Clinton, 687

F. Supp. 1310, opinion on remedy, 687 F. Supp. 1361

(E.D. Ark.), aff’d, 109 S. Ct. 548 (1988).)

5Appellees also claimed that intentional discrimination

in drawing the 1981 plan and numerous other Fifteenth

Amendment violations by State and local officials justified

placing Arkansas under pre-clearance procedures pursuant

to § 3(c) o f the Voting Rights Act, 42 U .S.C . § 1973a(c)

(1981). In a separate, unreported opinion and order

entered May 24, 1990, the District Court granted partial

relief on this claim. A Notice o f Appeal from this decision

was filed on June 13, 1990.

- 3 -

on each o f the factors identified by this Court in Thornburg

v. Gingles, 478 U .S. 30 (1986), concluding that violations

of § 2 had been proved as to the eastern and southern

Arkansas legislative districts. J.S. App. 35-36, 39. The

Court gave the current Board o f Apportionment an

opportunity to submit a remedial districting plan, which the

Court accepted in part and modified in part to assure that

black citizens whose rights had been violated would have

an adequate opportunity to participate in the political

process and to elect representatives o f their choice in the

1990 legislative contest.6 Under the remedy plan, the

number o f majority-black districts increased from one to

three in the Senate and from five to twelve in the House.

6The next General Assembly elections in Arkansas will

be subject to a new redistricting plan to be devised when

the results o f the 1990 Census are available.

- 4 -

REASONS FOR SUMMARY AFFIRMANCE

Summary affirmance is appropriate in this case

because the court below simply applied settled legal

principles to the facts which it found based on ample

evidence presented at trial. No substantial legal questions

meriting plenary consideration are raised by appellants.7

Indeed, both before and after its seminal interpretation of

§ 2 in Thornburg, the Court summarily affirmed two § 2

cases on facts very similar to those proved below.

In Smith v. Clinton, 109 S. Ct. 548 (1988), aff'g

687 F. Supp. 1310 (E.D. Ark. 1988), an eastern Arkansas

multi-member House district was invalidated under § 2

based on findings nearly identical to those made below,

7This case does not present the issues raised in the

pending Petitions for Certiorari in Sanchez v. Bond, No.

89-353, and City o f Norfolk v. Collins, No. 89-989,

concerning the impact on § 2 claims o f minority voter

support for white candidates. Here, as in Thornburg, no

statistical evidence was introduced concerning voting

patterns in elections where there was no black candidate,

and the evidence o f racial bloc voting in elections where

there was a black candidate was overwhelming.

- 5 -

except that "the record made in this case is much fuller

than the one made in Smith” and thus the findings are more

detailed, J.S. App. 25. In Mississippi Republican

Executive Committee v. Brooks, 469 U .S. 1002 (1984),

affig Jordan v. Winter, 604 F. Supp. 807 (N .D . Miss.

1984), a single-member congressional district was held to

violate § 2 because "it combined the majority black Delta

area with six predominantly-white eastern counties to create

a district which was majority white in voting age

population." Brooks, No. 83-1722, Motion to Affirm 4-5.

As we demonstrate briefly below, the judgment in this

action should also be summarily affirmed because it

correctly applies the statute and the teaching o f the decision

in Thornburg.

- 6 -

A. T he Judgm ent Is Supported by

Unimpeachable Findings on the Relevant

Factors Identified in Thornburg and a Fully

Supported Conclusion, Based on the Totality

of the Circumstances, that Black Citizens’

Opportunity to Participate in the Political

Process and to Elect Representatives of Their

Choice Was Limited and Denied by the 1981

General Assembly Districting Plan,_________

In its opinion, the court below articulated the

applicable standards for evaluating a claim that § 2 of the

Voting Rights Act was violated by legislative districting:

Dilution may be much more obvious in a

case like Smith where a potential majority of

black voters was submerged in a two-

member district. But the basic principle is

the same. If lines are drawn that limit the

number of majority-black single-member

districts, and reasonably compact and

contiguous majority-black districts could

have been drawn, and if racial cohesiveness

in voting is so great that, as a practical

matter, black voters’ preferences for black

candidates are frustrated by this system of

apportionment, the outlines o f a Section 2

theory are made out. Whether such a claim

will succeed depends on the particular factual

context, including all of the factors that

Thornburg, Smith, and the legislative history

of Section 2 say are relevant.

- 7 -

J.S. App. 16. The trial court carefully applied § 2 to the

"particular facts" and made well-supported determinations

on each of the relevant factors.

1. Size and geographic compactness o f

the minority group. (478 U .S. at 50

and n.17)

The District Court found that "black communities in

the areas o f the State challenged by plaintiffs are

sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute

a majority in single-member districts." J.S. App. 17.

Appellees had presented evidence that, using the data

available in 1981, two additional, majority-black VAP

Senate districts, and seven additional, majority-black VAP

House districts could readily have been created.8 *

*These "alternative districts" were presented not as

proposed remedies but to establish, as Thornburg requires,

that the black population was sufficiently large and

geographically compact to constitute majorities in single

member districts. In fact, the remedy ultimately adopted

by the court below differed significantly from the

"alternative districts" configuration presented at the liability

hearing. As was true o f the challenged 1981 plan, each

"alternative district" presented by the appellees included

(continued...)

- 8 -

Appellants’ principal complaint about the compactness

finding is that some o f the appellees’ exemplary majority-

black VAP districts would have required the splitting of

municipalities among legislative districts; however, the

court below found that the 1981 plan followed no

consistent policy o f maintaining political subdivision

boundaries, and that counties, cities and townships were all

divided by the Apportionment Board to accomplish various

goals, ranging from compliance with one-person, one-vote

requirements to the protection o f incumbents, J.S. App.

34. The alternative districts in Thornburg split counties, 8

8(... continued)

portions of one to four Arkansas counties.

Although the District Court referred to 16

"alternative districts," e.g., J.S. App. 17, this number

includes the majority-black VAP districts that already

existed at the time of trial (one Senate district and four

House districts created under the 1981 plan and the House

district established as part o f the remedy in Smith v.

Clinton), as well as the additional House district in Little

Rock sought by appellees. Thus, in eastern and southern

Arkansas (the areas in contention on this appeal) a total of

nine, new, majority-black VAP "alternative districts" were

presented.

- 9 -

and the District Court’s reasoning there is equally

applicable to the splitting o f a few municipalities here:

"To the extent that the policy ... was to split counties when

necessary to meet population deviation requirements or to

obtain § 5 preclearance o f particular districts ... such a

policy obviously could not be drawn upon to justify, under

a fairness test, districting which results in racial vote

dilution." Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345, 355

(E .D.N.C. 1984), aff’d in part and rev’d in part on other

grounds sub nom. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U .S. 30

(1986).9

2. Racially polarized voting. (478 U .S.

at 52-58)

The District Court had "little difficulty in finding

that voting patterns [throughout the districts challenged by

appellees] are highly racially polarized." J.S. App. 20.

“The dissent below agreed that the 1981 district lines

diluted black voting strength in at least three districts. See

J.S. App. 156 (Phillips County), 156-160 (Ashley, Desha

and Chicot counties), 164 (Jefferson County).

- 10 -

This finding was based on overwhelming evidence, both

statistical and narrative, concerning elections in the areas

covered by the challenged or ''alternative" districts.10

10Dr. Richard Engstrom, an expert witness whose work

was cited with approval in Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 46, 48,

53, 55, analyzed every election since 1978 in which a

black candidate ran for the General Assembly; he also

examined racial voting patterns in 36 separate contests

since 1976 (constituting all of the countywide election

contests between a black and white candidate for which

data were available in the relevant counties); and he studied

two Congressional races and the Jesse Jackson presidential

primary results in eleven Arkansas counties. He subjected

each set of election returns to the standard methods of

bivariate ecological regression and homogeneous precinct

analysis employed in Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 52 & n.20,

53. Regardless of the method used, the results consistently

revealed a "pronounced and persistent" pattern o f racially

polarized voting "across counties, across candidates, and

across time." PX 3, at 2 [Engstrom written report].

Appellees also presented narrative testimony about

racial polarization in election contests from the areas of the

State in which districts were challenged. See, e.g., TR Oct.

2, 1989 (afternoon) 5, 6-7, 8 (Sam Whitfield), III 141-

142, 144, 145, 146, 167 (Lonnie Middlebrook), Oct. 2,

1989 (morning) 66-68, 70-75, 77, 79-85 (Robert White),

III 33, 57, 61-62 (Roy Lewellan), IV 184-187, 189 (Jean

Edwards), IV 88-89, 97-98, 103 (Andrew Willis). Two

white legislators who testified for the defendants admitted

that voting was racially polarized in their districts. TR X

49, 146.

(continued...)

- 11 -

Appellants assert that plaintiffs did not prove political

cohesion among black voters in the hypothetical

"alternative districts" because these were districts "in

which the voters had never voted together before on state

legislative races," J.S. 18. Since these were by necessity

hypothetical districts, plaintiffs proved political cohesion in

the only way possible — by establishing the existence of 10

10( . . .continued)

The dissenting opinion below concluded that blacks

are politically cohesive in seven districts. J.S. App. 147,

151, 155, 158. The dissent also concluded that plaintiffs

proved legally significant racially polarized voting in

Crittenden, Phillips, Monroe, Chicot, Desha, Lee,

Jefferson and Ouachita counties, counties which include a

substantial part o f each o f the alternative districts. J.S.

App. 150, 151-152, 155, 157, 161-162, 163, 168. The

dissent incorrectly reports that plaintiffs introduced no

evidence o f racially polarized voting in Mississippi, St.

Francis, Ashley and Lincoln counties. J.S. App. 150, 162,

167, 157. For St. Francis County evidence, see TR III

179-80, 185-186 (blacks receive 90-97% of vote in black

wards and 1% in white wards), 188, 189 (only 1 white

leader in county has ever publicly supported a black

candidate), IV 154, 155, 162. For Mississippi County,

see TR in 141-142, 144, 145, 150, 167. For Ashley

County, see TR V 100-102. For Lincoln County, see PX3

(Engstrom report) at 12.

- 12 -

severe racially polarized voting in the component counties

and showing that this racial polarization crossed county

lines in state legislative elections and the 1988 presidential

primary.11 As the Court recognized in Thornburg,

Where a minority group has never been able

to sponsor a candidate, courts must rely on

other factors that tend to prove unequal

access to the electoral process. Similarly,

where a minority group has begun to sponsor

candidates just recently, the fact that

statistics from only one or a few elections

are available for examination does not

foreclose a vote dilution claim.

478 U .S. at 57 n .25.12 The record in this case is replete

“Voting patterns in the 1988 presidential primary

clearly establish that black voters in Arkansas are cohesive

across county lines. In the 11 counties for which data was

available, the percentage of the black vote for Rev. Jackson

ranged from 81.5 to 97%. PX 3, at 12 (single regression

analysis).

12Appellants complain that appellees "could find only

ten races for legislative seats in which black candidates ran

against white candidates" and claim that it was improper

for the District Court to rely on exogenous [non-legislative]

elections." J.S. at 18-19. In a situation where the District

Court explicitly found that black candidates for the

legislature were subjected to retaliation and did not run

because they knew the effort would be futile, J.S. App. 26-

(continued...)

- 13 -

with evidence o f "other factors" that support the District

Court’s finding that racially polarized voting exists in each

of the challenged districts.13

12(... continued)

27, 31, the Court’s reliance on countywide data and

narrative testimony is clearly appropriate.

The dissent below contends that appellees were

required to demonstrate that the 1981 district lines split

politically cohesive groups of black voters who had been in

the same district under the 1971 districting plan for the

General Assembly. J.S. App. 93-94. Such a requirement

would transform the § 2 "results" test into the

"retrogression" standard under § 5 o f the Voting Rights

Act. The fact that a state has always fractured

geographically compact groups of black voters does not

insulate a districting plan from challenge under § 2.

13The District Court found that ”[t]o this day, [in

southern and eastern Arkansas] the races live separately,

. . . they go to church separately, and they even die

separately. . . . [A]s late as October 2 o f [1989], the City

of Marianna was maintaining, at public expense, a

cemetery for whites only." J.S. App. 30. Governor

Clinton, one of the appellants, stated in 1986 that ”[t]here

is no question in my mind that those counties have been

held back by the dominance o f what I call the old

plantation attitudes over there about what the proper place

o f blacks is and what the proper place o f whites is." PX

30gg at 3, TR VII 103. Governor Clinton also stated that

campaign events in which he participated were segregated

by race until at least 1986. PX 30gg at 3, TR VII 103-

104.

- 14 -

3. History o f discrimination and present

effects o f discrimination. (478 U.S.

at 44-45)

"[TJhere is a long history o f official discrimination.

It has a present effect. And some instances o f it are still

occurring." J.S. App. 27. These findings were based on

extensive evidence presented at trial which showed recent

and continuing barriers to black political participation in

the areas o f the State where General Assembly districts

were challenged.14

14For example, the court below found, based on that

evidence, that:

Polling places have been moved on short

notice; deputy voting registrars have, with

isolated exceptions, been appointed only as a

result o f litigation; efforts have been made to

intimidate black candidates. . . . [Tjhese and

similar practices clearly result in

discouraging black participation in elections.

J.S. App. 26. The court also found that black candidates

had suffered violence, harassment, intimidation and

criminal prosecution on false charges. Id. "This kind of

intimidation no doubt had a powerful chilling effect." Id.

at 27. See Lewellen v. Raff, 649 F. Supp. 1229 (E.D.

Ark. 1986)(injunction against criminal prosecution

(continued...)

- 15 -

4. Racial appeals in political campaigns. (478

U.S. at 45).

The District Court found: "Racial appeals, some

quite offensive, are common in campaigns in which a white

candidate is running against a black candidate." J.S. App. 14

14(... continued)

commenced in retaliation for decision o f black attorney in

eastern Arkansas to run for office), aff'd, 843 F.2d 1103,

opinion modified, 851 F.2d 1108 (8th Cir. 1988), cert,

denied, 109 S. Ct. 1171 (1989).

The District Court also found that "the history of

discrimination has adversely affected opportunities for

black citizens in health, education and employment. The

hangover from this history necessarily inhibits full

participation in the political process." J.S. App. 14.

"Many more whites than blacks are high-school graduates,

and many blacks were educated in schools that were both

separate (by compulsion o f law) and unequal. . . .

[P]overty among blacks is more nearly the rule than the

exception. Blacks tend to have fewer telephones and fewer

cars. If a person has no phone, cannot read, and does not

own a car, the ability to do almost everything in the

modem world, including vote, is severely curtailed." Id.

at 27. See also id. at 28 (county-by-county chart showing

socio-economic status o f blacks and whites in areas of

education, income, families living in poverty and

availability o f telephones and vehicles).

- 16 -

29 .15 Appellants do not challenge the lower court’s finding

o f fact on this subject.

5. The extent to which blacks have been

elected. (478 U .S. at 45)

The District Court found that black candidates were

successful only in those few legislative districts that had a

15In 1975, for example, a supporter of a white

candidate for Mayor of Pine Bluff publicly warned that "if

white voters didn’t turn out, there would be a black

mayor." J.S. App. 30. In a black candidate’s campaign

for County Judge in Desha County, the white incumbent

used "profanity and a racial epithet" at a public rally. Id.

The dissenting opinion below expresses "supris[e] at

how little evidence o f overt or subtle racial appeals

plaintiffs were able to produce." J.S. App. 135. In fact,

plaintiffs introduced evidence of numerous racial appeals

made by white candidates and their authorized

representatives. See TR III 62-63 (white candidate for

state legislature in Lee, Phillips and Monroe counties in

1986 stated to whites "you know he’s black," about

opponent as part of campaign strategy), IV 150-52 (in 1986

white candidate for mayor o f Forrest City (St. Francis

County) mailed out leaflet to white neighborhoods featuring

picture o f black opponent), V 98-99 (campaign worker for

white candidate for legislature in Jefferson County in 1982

made telephone calls to voters in white neighborhoods

stating that opponent was black), V 94-95 (in 1978 state

representative election in Jefferson County, white

incumbent ran newspaper advertisement with a photograph

of his black opponent).

- 17 -

black voting majority. J.S. App. 31. Until the decision in

Smith v. Clinton, no black had been elected to the General

Assembly from the Arkansas Delta region.16 No black

candidate (at least since Reconstruction) had ever won a

statewide election or a countywide election in any of

Arkansas’ 75 counties. Id. Appellants do not challenge

these findings.

6. Use of majority-vote requirements.

(478 U.S. at 45)

The District Court found that Arkansas has "a

majority vote requirement affecting races for the General

Assembly and many other public offices." J.S. App. 29.

Appellants do not challenge this finding.17

16Prior to Smith, only one legislative district outside

Pulaski County (Little Rock) had ever sent a black person

to the General Assembly.

17In its decision on appellees’ pre-clearance claim, see

supra note 5, the court found that the General Assembly

acted with discriminatory intent in enacting four different

majority-vote statutes since 1972. Slip Op. May 24, 1990.

- 18 -

7. Lack o f responsiveness o f elected

officials. (478 U.S. at 45)

Although "there is a widespread feeling . . . among

black voters" that "white legislators in the Delta are

insensitive to the concerns of poor black people," J.S.

App. 31, the District Court ruled that "the charge that

white legislators in the Delta are unresponsive to black

needs has not been proved to our satisfaction on this

record," id. at 32.

8. Other factors. (478 U.S. at 45)

On the strength o f the policy underlying the 1981

plan, the District Court concluded: "There are a number

of crosscurrents here, and they point in various directions.

On the whole, we are not persuaded that this factor has

much weight." J.S. App. 35. The Court found that the

other factors listed in the Senate Report and discussed in

Thornburg had no applicability to this case: candidates run

for a designated seat and thus single-shot voting would

have no practical significance; none o f the challenged

- 19 -

districts was unusually large; "[a]s far as we know the

process o f slating plays no part in races for the Arkansas

Legislature." Id. at 29.

9. The totality o f the circumstances.

(478 U .S. at 46)

The District Court balanced the totality o f the

circumstances in each o f the districts challenged by

appellees. In "the Delta, the Jefferson County area, and

the Ouachita-Nevada counties area as a group," the Court

found: "On balance a clear answer emerges. In these

areas, black political opportunity is significantly lessened

by the 1981 apportionment plan, and the plan violates

Section 2 o f the Voting Rights Act." J.S. App. 35-36. In

the Little Rock area, the Court found that "the whole

political atmosphere, with respect to black opportunity and

participation, seems more open," id. at 38, and rejected

appellees’ claims.

The trial court’s careful application o f the "totality

of the circumstances" approach required by the statute and

- 20 -

by Thornburg refutes appellants’ repeated assertions that

the Court maximized black voting strength or required

proportional representation.18 Moreover, had the District

Court been driven by proportional representation as the

measure o f liability it would have found in favor of

plaintiffs’ Little Rock claim.19

B. The Legal Issues Sought to be Raised by

Appellants Do Not Merit Plenary Review in

this C ase._______________

As we have summarized above, the District Court

carefully assessed the evidence and made appropriate

findings on each of the factors identified in the statute,

nSee, e.g., J.S. 14, 23. The District Court expressly

adhered to the statutory provision that "members o f a

protected class have no right to be ’elected’ in numbers

equal to their proportion to the population. 42 U .S.C . §

1973(b)." J.S. App. 30.

19The District Court found that the factors present in

eastern and southern Arkansas also existed to a significant

degree in Little Rock and that a fourth compact and

contiguous, majority-black district could be drawn in Little

Rock. J.S. App. 36-38.

- 21 -

according to the framework established by the Court’s

ruling in Thornburg. Indeed, if anything, the record and

findings below are even more compelling than in

Thornburg. The only distinction between the cases is that

here the challenge involved single-member rather than

multi-member districting. Appellants urge that this

distinction justifies plenary consideration o f this matter.20

However, although the question was formally pretermitted

by the Court in Thornburg, 478 U .S. at 46 n.12, the Court

explained that (478 U .S. at 50 n.16):

In a different kind o f case, for example a

gerrymander case, plaintiffs might allege that

the minority group that is sufficiently large

and compact to constitute a single-member

district has been split between two or more

multi-member or single-member districts,

with the effect o f diluting the potential

strength o f the minority vote.21

20,1 [T]he Gingles formulation does not fit neatly in a

single-member district situation." J.S. 15.

21Justice O’Connor also noted:

There is no difference in principle between

(continued...)

- 22 -

As noted previously, in Mississippi Republican Executive

Committee v. Brooks, 469 U.S. 1002 (1984), this Court

summarily affirmed a lower court decision that precisely

this violation o f § 2 had occurred in the creation o f a

congressional district.21 22 Because the District Court in this

case carefully and correctly followed the road map

provided by Thornburg, further review is inappropriate and

unnecessary.

21( . . .continued)

the . . . varying effects o f alternative single-

district plans and multi-member districts.

The type o f districting selected and the way

in which district lines are drawn can have a

powerful effect on the likelihood that

members o f a geographically and politically

cohesive minority group will be able to elect

candidates of their choice.

478 U .S. at 87 (concurring opinion).

22Accord Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345, 355

(E .D.N.C. 1984), aff’d in part and rev’d in part on other

grounds sub nom. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U .S. 30

(1986); Neil v. Colebum, 689 F. Supp. 1426 (E.D. Va.

1988); Ketchum v. Byrne, 740 F.2d 1398 (7th Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 471 U .S. 1135 (1985); Major v. Treen, 574

F. Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983). (There is no conflict

among the lower courts on this point.)

- 23 -

Neither the Jurisdictional Statement nor the dissent

below properly raise any question o f law that remains

unanswered after Thornburg. Appellants’ first "Question

Presented" — whether § 2 requires a showing that minority

citizens have both less opportunity to participate in the

political process and less opportunity to elect candidates of

their choice — does not arise here since the District Court

explicitly found that appellees proved both a lesser

opportunity to participate and a lesser opportunity to elect.

J.S. App. 9-10. The court below expressly rejected

appellants’ assertion that black citizens in eastern and

southern Arkansas "have just as much opportunity to

participate in the political process as anyone else," finding

that "[t]his argument fails to reckon with the present effects

of past racial discrimination, much of it official and

governmental." J.S. App. 14.

The second "Question Presented" in the

Jurisdictional Statement — whether Thornburg was correctly

- 24 -

applied, is merely a disagreement with the court below on

factual issues, and the District Court’s findings of fact must

be affirmed unless clearly erroneous, 478 U .S. at 78-79.

Appellants fail to identify any specific finding that is

clearly erroneous and, as we have shown above, the

findings are well supported in this record.

The third "Question Presented" — whether the court

below properly ordered that the remedy include three

legislative districts having effective black VAP majorities

— raises no substantial legal issue. Once a violation o f § 2

was found, the District Court simply and correctly applied

the same remedial principles enunciated in Thornburg and

other cases to insure that black citizens whose voting

strength had been diluted under the 1981 plan would have a

realistic opportunity to participate in political contests and

to elect candidates. See United Jewish Organizations v.

Carey, 430 U .S. 144, 162 (1977)(minority districts "at a

minimum and by definition . . . must be more than 50%

- 25 -

black . . . [in order] to ensure the opportunity for the

election o f a black representative"); Beer v. United States,

425 U .S. 130, 141-42 (1976); City o f Richmond v. United

States, 422 U .S. 358, 370-71 (1975); White v. Regester,

412 U .S. 755, 768 (1973).23 The District Court did

“The District Court accepted without modification six

of the Apportionment Board’s nine remedial districts. The

record clearly supports the Court’s conclusion that three of

the Board’s eastern Arkansas districts did not create

effective black-majority VAP districts and would not cure

the violations, J.S. App. 197-98. In addition to the

unrefuted evidence of lower voter registration and turnout

among blacks, e.g. TR Oct. 2, 1990 (morning) 52, and

severe racially polarized voting, PX3, the court below

found that in eastern Arkansas, the "center o f the black

population," id. at 200, official discrimination calculated to

have a "powerful chilling effect" on black political and

electoral participation, id. at 27 and depressed

socioeconomic conditions, id. at 28, were particularly

egregious.

The District Court also correctly concluded that

these three districts drawn by the Apportionment Board

themselves violated § 2. Appellees’ expert witness gave

uncontradicted evidence that the configuration o f these

districts continued to fracture black population

concentrations; the Apportionment Board rejected less

dilutive options and chose lines that artificially depressed

black voting majorities and favored incumbents, J.S. App.

200; and the court found that there was no legitimate state

(continued...)

- 26 -

nothing more than "exercise its traditional equitable powers

so that it completely remedie[d] the prior dilution o f

minority voting strength and fully provide[d] equal

opportunity for minority citizens to participate and to elect

candidates o f their choice." S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong.,

2d Sess. 31 (1982).23 24

23 (.. .continued)

policy or "neutral, nondiscriminatory reason" for drawing

the district lines submitted by the Apportionment Board,

J.S. App. 200, and that the Board was motivated by a

desire to protect white incumbents at the expense of black

challengers, id.

Governor Clinton, one of the appellants, objected to

the Board’s House plan because in seeking to protect an

incumbent in eastern Arkansas, it spumed "the best

opportunity to resolve the historic dilution o f black voting

strength in that region." J.S. App. 200. The Governor

submitted his own remedial House plan that included a

nonincumbent district in eastern Arkansas.

24Appellants’ assertion that the District Court remedy

maximized black voting strength is patently false. Directly

at odds with such a goal, the court below rejected

modifications which appellees had proposed to increase the

black VAP o f the Board’s new Senate district in southern

Arkansas explicitly because "black voters [must] have equal

opportunity, [but] we do not think [the Apportionment

Board] should be faulted for failure to give black voters an

additional edge," J.S. App. 202.

- 27 -

Finally, the District Court did not abuse its

discretion in rejecting appellants’ laches claim.23

The dissenting opinion below is founded on a

^Laches is a discretionary, equitable doctrine that

involves a balancing o f all o f the circumstances. Czaplicki

v. The S.S. Hoegh Silvercloud, 351 U .S. 525, 534 (1956).

Here the District Court concluded that the balance lay in

favor o f appellees’ claims. J.S. App. 12. There is no

reason for this Court to second-guess that balancing of the

equities.

In any event, appellants did not meet even the

minimum requirements to make out a claim o f laches,

because they did not prove either unreasonable and

inexcusable delay in appellees’ assertion o f their rights or

material prejudice resulting from that delay, Costello v.

United, States, 365 U .S. 265, 282 (1961); Gardner v.

Panama Railroad Company, 342 U .S. 29, 31 (1951). The

economic harm alleged in this Court, see J.S. 25-26, is

directly attributable to the State’s violation of the Voting

Rights Act, not to any delay on the part o f appellees. In

addition, the cost o f remedying the violation — the process

of redistricting — has already been incurred and proved to

be neither prohibitive nor significantly disruptive. Finally,

although appellants argued that "there is absolutely no

reason to believe that districts drawn according to [the

remedial orders below] will produce different electoral

results" from the 1981 plan, id. at 26, the May, 1990

primary elections held under the new plan produced results

dramatically different from any past election. Black

candidates won every election in which they ran in the

newly configured districts.

- 28 -

passionate disagreement with the fundamental premises of

the Voting Rights Act, as clarified by the 1982

amendments.26 It does not identify clearly erroneous

^However intense the feelings o f the dissenting judge,

his basic disagreement is with the Congressional policy

choice and it provides no justification or need for this

Court to engage in plenary review o f the faithful

implementation o f Thornburg and the legislative history of

§ 2 by the court below. For example, the dissent imports

an intent requirement into § 2, in direct contravention of

Thornburg, 478 U.S. at 70-74; id. at 83 (concurring

opinion), and the 1982 amendments. The dissent also

disregards much o f the record evidence on the factors

which Thornburg indicated should be canvassed in a § 2

case because, in its view, "some o f the actual Senate

factors may have no more relevance than the extent to

which minority group members drink coffee." J.S. App.

74. The dissent would limit consideration o f the factors

identified in the legislative history to cases challenging "a

voting literacy test or a financial burden test (e.g., poll

tax)," id. at 120, apparendy excluding their relevance even

to at-large challenges in direct contravention of the

approach outlined by this Court in Thornburg.

Indeed, while it accuses the appellees o f having

failed to establish that black citizens in the challenged

districts have "less opportunity than others to participate in

the political process," id. at 62, the dissent would limit §

2 ’s coverage to direct impediments to a black citizen’s

opportunity to register, to enter a polling booth and to pull

the lever, id. at 64. The dissent does not, however,

dispute the majority’s finding that "the diminished socio-

(continued...)

- 29 -

findings o f fact27 or any legal errors which this Court

% .. continued)

economic status found to have resulted from prior

discrimination" results in blacks having "less opportunity to

participate in the political process," J.S. App. 85.

Reduced to its essence, therefore, the dissent simply

refuses to make the judgment required by the Act and by

Thornburg on the basis o f the "totality o f the

circumstances."

27The dissenting opinion below, in concluding that

current discriminatory voting practices are "isolated," J.S.

App. 125, ignores overwhelming evidence in the record.

Plaintiffs introduced uncontroverted evidence that polling

places in black wards were routinely moved during the two

weeks before the election and that no notice was posted at

the old location, e.g . , TR Oct. 2, 1989 (morning) 18-21,

IV 172-173, 176 (Phillips County), III 130-132 (Chicot

County; black ward polling places moved at least twice in

last five years), IV 127-130 (Chicot County), III 157-159

(Mississippi County), and that polling places for black

wards are placed in inhospitable, inconvenient and

inaccessible locations, such as the City jail, TR III 130,

136 (Chicot County), and a white country-western club

distant from the black community, TR Oct. 2, 1989

(afternoon) 33-35 (Lee County), III 44-46 (Lee, Phillips,

Monroe counties), IV 129-130 (Chicot County), IV 173

(Phillips County).

Plaintiffs also showed that in many counties

virtually all o f the election judges, sheriffs o f the day and

clerks were white persons, such as farmer’s wives in areas

where blacks worked on white-owned farms, who

intimidated and discouraged black voters. E.g. TR III-51

(continued...)

- 30 -

^(...continued)

(Lee County), III 173-174 (Phillips County), III 125-26

(Chicot County) (in 1988 voting booths provided in white

wards but not in black wards thus depriving black voters of

ballot privacy), IV 118-119 (white candidates inside the

polling place; black candidates not allowed inside), IV

123 (all Chicot County election judges are white), IV 124

(paper ballots filled out on a plain table and white election

judge looks over shoulders), III 151-54, 155-56, 161

(Mississippi County).

In Desha and Ashley counties, white poll officials

refused to allow illiterate black voters to be assisted by

relatives and blacks who challenged the practice were

physically threatened, TR IV 92-96, V 107-109.

The dissenting opinion also accuses the majority of

using a "scattershot" approach and of failing to analyze

each challenged district separately, but the record and the

findings refute this charge. Appellees introduced

overwhelming evidence on each relevant factor in each

challenged area. The evidence showed that eastern and

southern Arkansas share a common plantation history

replete with official and private discrimination having

continuing present effects, and that extreme racially

polarized voting, racial campaign appeals, intimidation of

candidates and other currently effective barriers to black

political participation characterize the entire region. It was

unnecessary for the District Court to repeat the same

factual findings over and over for each separate district.

Instead, the Court found that this pattern existed across

eastern and southern Arkansas, in every affected county

and legislative district. When the trial court found a

departure from this pattern, in Little Rock, it described it

(continued...)

- 31 -

should correct, or could correct after a careful review o f

the massive evidentiary record in this case.

27( . . .continued)

as an exception to the general pattern and found no § 2

violation, J.S. App. 35-37. In eastern and southern

Arkansas, there was no exception to the pattern, as the trial

court explicitly found. J.S. App. 35-36.

- 32 -

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment o f the

District Court should be affirmed summarily.

Respectfully submitted,

P.A. HOLLINGWORTH

415 Main Street

Little Rock, AR 72201

(501) 374-3420

OLLY NEAL

33 North Poplar Street

Marianna, AR 72360

(501) 295-2578

DON E. GLOVER

P. O. Box 219

Dermott, AR 71638

(501) 538-9071

L. T. SIMES

P. O. Box 2870

West Helena, Arkansas

72390

(501) 572-3796

PENDA D. HAIR*

SHEILA Y.THOMAS

1275 K Street, N.W .

Suite 301

Washington, D.C.

20005

(202) 682-1300

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

DAYNA L. CUNNINGHAM

99 Hudson Street,

16th floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

*Counsel o f Record

July 25, 1990

- 33 -