Miller v. Johnson Motion to Affirm

Public Court Documents

December 23, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. Johnson Motion to Affirm, 1994. bbb211ac-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a844663c-88fa-4ee7-b23d-3b9d4f268fe3/miller-v-johnson-motion-to-affirm. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

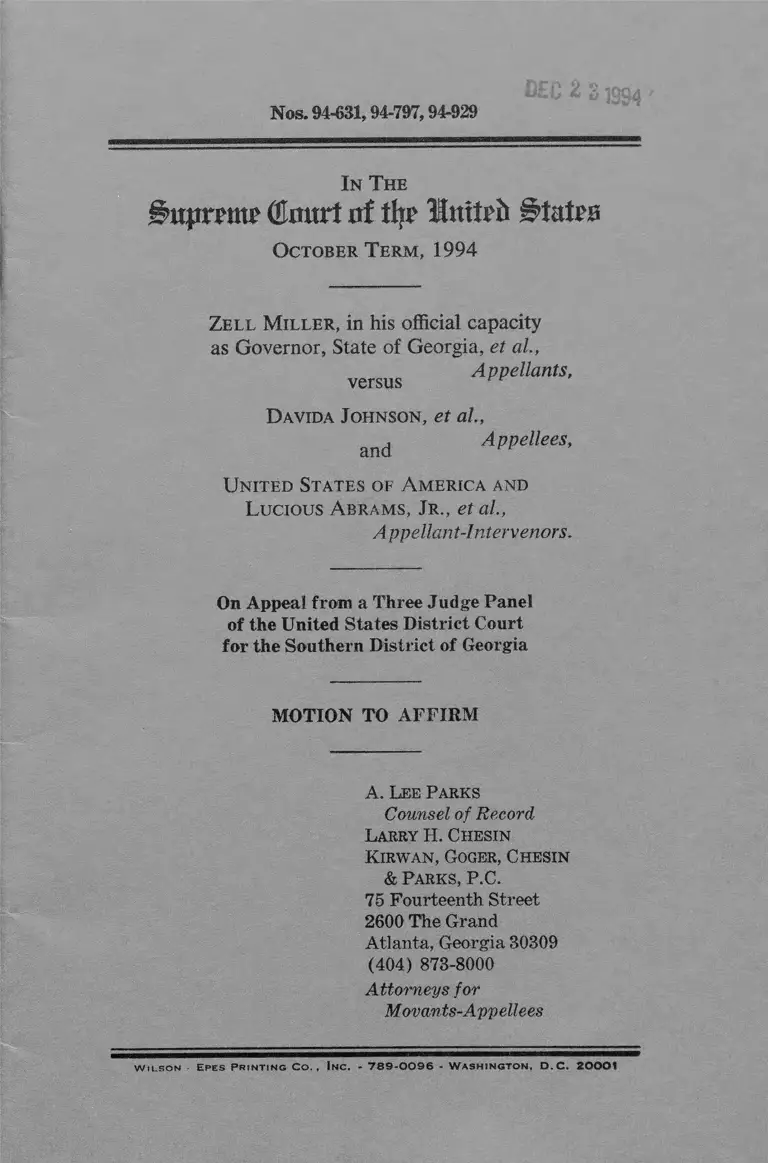

Nos. 94-631,94-797,94-029

In T he

Ihqiremr (Emtrt rtf tfy? HUnxtrb States

October T erm , 1994

Zell M iller , in his official capacity

as Governor, State of Georgia, et al.,

Appellants,versus

D avida J ohnson, et a l ,

and Appellees,

United States of A merica and

L ucious Abrams, Jr ., et al,

A ppellant-Intervenors.

On Appeal from a Three Judge Panel

of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Georgia

MOTION TO AFFIRM

A. Lee Parks

Counsel of Record

Larry H. Chesin

Kirwan, Goger, Chesin

& Parks, P.C.

75 Fourteenth Street

2600 The Grand

Atlanta, Georgia 30309

(404) 873-8000

Attorneys for

Movants-Appellees

W i l s o n E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n , D , C . 2 0 0 0 1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether the District Court’s finding of a racial

gerrymander is reviewed under the clearly erro

neous standard?

II. Whether the decision below presents any substan

tive departure from the holding of Shaw v. Reno

which defined the constitutional limits the Four

teenth Amendment places on race based reappor

tionment legislation?

III. Whether Georgia’s admission that racial gerry

mandering occurred as a direct consequence of the

Justice Department’s demand Georgia maximize

black voting strength without due regard for tradi

tional districting principles mandates summary

affirmance of the decision below?

IV. Whether the absence of any legal obligation under

the Voting Rights Act to maximize black voting

strength in derogation of Georgia’s traditional dis

tricting principles pretermits any contention that a

compelling interest was furthered by this race based

district?

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED........................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................... v

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...................................... 2

ARGUMENT................... .................................................. 6

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S CONCLUSION

THAT RACIAL GERRYMANDERING RE

SULTED IN A BIZARRELY CONFIGURED

DISTRICT IS REVIEWED UNDER THE

CLEARLY ERRONEOUS STANDARD........ 6

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY HELD,

IN ACCORDANCE WITH SHAW v. RENO,

THAT GEORGIA’S LEGISLATION CREAT

ING THE ELEVENTH CONGRESSIONAL

DISTRICT VIOLATED THE PLAINTIFFS’

RIGHT TO EQUAL PROTECTION.................. 8

III. GEORGIA’S UNPRECEDENTED AND EX

TREME DEPARTURE FROM ITS TRADI

TIONAL DISTRICTING PRINCIPLES FOR

PURELY RACIAL REASONS IS SUBJECT

TO STRICT SCRUTINY..................................... 18

IV. COMPLIANCE WITH THE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT CAN NOT CONSTITUTE A COMPEL

LING GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST IN

THIS CASE SINCE THE STATE AFFIRMA

TIVELY DISAVOWED THE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT AS ITS RATIONALE FOR THE REDIS

TRICTING LEGISLATION.................. ............ 15

A. A Congressional District Which Is Bizarrely

Configured And Is Overly Safe From The

Vantage Point Of Assuring The Election Of

A Black Representative, Is Not Narrowly

Tailored To Further A Compelling Govern

mental Interest ................................................ 16

(iii)

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

V. GEORGIA DOES NOT HAVE A COMPEL

LING GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST IN

PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION OF

MINORITIES........................ 18

VI. THE ABRAMS INTERVENORS SHOULD

NOT BE PERMITTED TO PARTICIPATE

IN ANY PLENARY REVIEW OF THIS

CASE................................................................... 21

CONCLUSION........................................ 24

APPENDIX

Population Density Map ....................... .................. App. 1

Race Map of Chatham County................................... App. 2

Race Map of Effingham County ....... .......... ....... . App. 3

Race Map of Richmond County .............. ......... ........ . App. 4

Race Map of DeKalb County............................. ........ App. 5

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, N.C., 470 U.S.

564, 105 S. Ct, 1504, 84 L.Ed. 518 (1985)).......... 7

City of Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co., 488 U.S.

469, 109 S. Ct. 706, 102 L.Ed.2d 854 (1989)----- 19

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 100

S. Ct. 1548, 64 L.Ed.2d (1980) ........................... 6

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339, 80 S. Ct. 669

(1960) ....................... ............................................- 8

Johnson v. DeGrandy, 114 S. Ct. 2647 (1994) ....17,18, 23

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 98 S. Ct. 2733, 57 L.Ed.2d 750

(1978)_____ _____ ___ - ........................- ............ 19

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 84 S. Ct. 1362

(1964) ......................... - .............................- ......... 2

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 102 S. Ct. 3272,

73 L.Ed.2d 1012 (1982) .... ................................... 6

Shaw v. Hunt, 1994 WL 457269 (E.D.N.C. Au

gust 1, 1994, as amended August 22, 1994 ......... 14

Shaw v. Reno,----- - U.S. —-— 113 S. Ct. 2816, 125

L.Ed.2d 511 (1993).................... passim

Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 478 U.S. 30, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1986) ................................ 6,15,20

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U.S. 364, 68 S. Ct. 524, 92 L.Ed.2d 746 (1948).. 7

White v. Regester, 412 U.S., 755, 93 S. Ct. 2332,

37 L.Ed.2d 314 (1973)........................................... 6

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52, 84 S. Ct. 603

(1964)............................................. -............. -......... 18

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazeltine Research, Inc.,

395 U.S. 100, 89 S. Ct. 1562, 23 L.Ed.2d 129

(1969) .... 7

CONSTITUTIONS

U.S. Const, amend. XIV, § 1....... ....................—-....... passim

STATUTES

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2 and 5 ............... ......... passim

RULES

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 (a )....

Supr. Court Rule 18.6

2

1

In The

i ’uprTmF (tart 0! ttjr Imtrb

October T erm , 1994

Nos. 94-631, 94-797, 94-929

Zell M iller , in his official capacity

as Governor, State of Georgia, et ah,

Appellants,versus

Davida J ohnson, et ah,

and Appellees,

U nited States of A merica and

L ucious A brams, Jr ., et al.,

A ppellant-Intervenors.

On Appeal from a Three Judge Panel

of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Georgia

MOTION TO AFFIRM

Pursuant to Rule 18.6, Appellees move this Court to

affirm the Order and judgment of the three judge panel

in this matter. Affirmance is appropriate in light of the

State’s own candid acknowledgement that it was forced

to enact a black vote maximization plan, concocted by

the American Civil Liberties Union and imposed on

Georgia by the Department of Justice which employed

racial gerrymandering as its modus operandi.

The issues upon which this case turns are fact intensive.

The District Court correctly concluded that the Eleventh

2

District’s shape was highly irregular—bizarre in the par

lance of these cases—due to racial gerrymandering. The

facts on which this pivotal finding is based are ex

haustively cataloged in the majority opinion. Given the

deference due those findings by this Court, affirmance

is warranted without further argument under Fed. R.

Civ. P. 52(a).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

With the completion of the 1990 census, states were

obligated to reapportion their Congressional districts to

bring them into conformity with the one man-one vote

ruling of Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 555 (1964). Prior

to the 1990 census, Georgia had ten (10) districts. Its

increased population entitled it to one additional seat.

(J.S. App. 5)

Since the 1980 census, there had been a quantum

leap in the technology of computer software available to

assist states in the reapportionment process. Racial data

for each census block (100 or less people) became the

building blocks employed to fashion districts with a racial

rather than geographical focus. (J.S. App. 12, n.6)

This case is ultimately between the State of Georgia

and the plaintiff citizens and voters of Georgia who ob

jected to the State’s decision to racially gerrymander the

boundaries of the Eleventh District. And the State does

not dispute any of the salient facts presented by Plain

tiffs which the District Court found to be true in connec

tion with the enactment of the reapportionment plan.

Miller, et al. Jurisdictional Statement [hereinafter Miller

J.S.] at p. 2. Those facts include the following:

(1) The District Court found Georgia was forced to

engage in racial gerrymandering by the Department of

Justice [hereinafter referred to as the DOJ] to maximize

the Black population in the Eleventh District. Georgia is

3

a state still under the jurisdiction of the DOJ for purposes

of reapportionment. The race based legislation the State

adopted was the DOJ’s quid pro quo for preclearance

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act [hereinafter,

the VRA]. (J.S. App. 26-27) It resulted in a district

that was unprecedented in Georgia’s history in terms of

its shape. The plan surgically segregated every major

population center south of Atlanta in order to maximize

the inclusion of Blacks and exclusion of whites within the

two new majority minority districts the DOJ required

the State create.

(2) “The amount of evidence of the General Assem

bly’s intent to racially gerrymander the Eleventh District

is overwhelming and practically stipulated to by the par

ties involved.” (J.S. App. 42-43). In its jurisdictional

statement, the State embraces the District Court’s de

scription of the process by which the Eleventh District was

created as “a search for [minority voting] maximization

by the crudest means, the pursuit of ‘maximization of the

black vote, whatever the cost’, and the like.” (Miller J.S.,

p. 3 quoting from the Opinion at App. 27, 11-12, n.4 28).

(3) During the 1990 reapportionment process, the

DOJ, in concert with the ACLU, pursued a policy of

minority vote maximization throughout the South. (J.S.

App. 11). Majority minority districts called “Max-Black”

plans were created by the ACLU, ostensibly for their

clients, then state legislators Cynthia McKinney and San

ford Bishop. Both were subsequently elected to Con

gress to represent the very Max-Black districts they

worked with the ACLU and DOJ to create. (J.S. App.

13 n.7).

(4) There was no evidence of any intent to discrimi

nate against minorities uncovered at any time during the

reapportionment process. (J.S. App. 13). Regardless of

that fact, the DOJ adopted the ACLU’s Max-Black ra

cial population quotas as the benchmarks for the three

majority minority districts the DOJ required Georgia to

4

create. Those percentages could not be attained without

resort to gerrymandering. As stated by the District Court:

“. . . [T]he slow convergence of size and shape between

the Max-Black plan and the plan the DOJ finally

precleared, bespeak a direct link between the Max-

Black plan formulated by the ACLU and the pre

clearance requirements imposed by the DOJ.” (J.S.

App. 26).

(5) The DOJ summarily rejected the first two plans

passed by Georgia’s legislature. (J.S. App. 13). In the

second rejection letter, the DOJ “suggested” the shape

the Eleventh District needed to take to meet the 65%

black population quota the ACLU had convinced the

DOJ was “possible” for the Eleventh even without the

Black population in Macon which was needed for the

other new Black Max district the DOJ wanted to create.

The only way to do that, according to the ACLU,

was for the Eleventh, anchored in Atlanta, to find a way

to get to Savannah. (J.S. App. 15-20) Georgia’s Attorney

General complained, to no avail, that the proposed con

figuration of the Eleventh District being advocated by

the DOJ/ACLU as violative “. . . of all reasonable stand

ards of compactness and contiguity.” (J.S. App. 19)

The DOJ was unmoved. Traditional districting principles

were then subordinated on a wholesale basis to further

the black maximization policies of the DOJ/ACLU by

drawing boundaries that specifically included Blacks and

excluded whites. Ms. Wilde, the ACLU attorney and

acknowledged architect of the gerrymandered District in

issue, was not apologetic: “That is how you draw a

majority black district.” (J.S. App. 20).

(6) The State, acting through its Director of the State

Reapportionment office, drew the Eleventh “as close as

she could to copying the Max-Black percentages. She was

prevented from exact duplication by the need to construct

eight other districts . . . .” (J.S. App. 22).1

1 The DOJ/ACLU team did not even bother with requiring the

Max-Black plan to be presented as a state-wide plan. The ACLU

5

(7) The twin forces that led to the racial gerrymander

in issue were the ACLU’s advocacy of a black vote maxi

mization policy and the DOJ’s misguided reading of the

VRA as obligating states to maximize black voting

strength wherever possible without regard to the resulting

aberrations in the shape and size of the district and the

fact states were forced to segregate voters on the basis

of their race. This de facto delegation of authority by

the DOJ to the ACLU was found by the District Court

to be an “embarassment.” (J.S.App. 26-27).

The dissenting judge adopted a “shape over substance”

approach to Shaw. In so doing, the dissent would turn

a deaf ear and blind eye to the machinations of the

ACLU and the DOJ’s abuse of its authority under the

VRA. The dissent believed the existence of a racial

gerrymander turned on the subjective opinion of the fact

finder as to the geometric shape of the District, independ

ent of where the people are concentrated and whether they

were intentionally racially segregated by this district’s

boundaries. With all due respect, the courts cannot hope

to offer the kind of continuity we expect of our juris

prudence if the standard is, essentially, a visceral one that

will vary from judge to judge and be materially impacted

by subjective perceptions that, in the end, are highly

personal spatial observations unrelated to any objective

standard.

just drew the Max-Black districts, and left the State to work out

the rest as best it could.

6

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT’S CONCLUSION THAT

RACIAL GERRYMANDERING RESULTED IN A

BIZARRELY CONFIGURED DISTRICT IS RE

VIEWED UNDER THE CLEARLY ERRONEOUS

STANDARD

This Court has made clear that findings of fact are

reviewed under the clearly erroneous standard. This is a

strict and longstanding rule. It has been expanded to

include ultimate findings in Voting Rights Act cases. See

Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S. Ct. 478 U.S. 30, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1986).

The standard is especially applicable in these types of

cases because of the importance of local factors and

geography in assessing whether a gerrymander has in

fected a districting plan. By analogy, this Court has

repeatedly held that the ultimate question of vote dilu

tion under the VRA is a finding subject to review under

the clearly erroneous standard:

“. . . [Ojur several precedents . . . have treated the

ultimate finding of vote dilution as a question of

fact subject to the clearly erroneous standard of Rule

52(a).” See, e.g., Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. at

622-627; City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S.

156, 183, 100 S.Ct. 1548, 1564 . . . (1980);

White v. Regester, 412 U.S., at 765, 770, 93 S.Ct.

at 2339, 2341.” Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S.Ct.

at 2780.

This same reasoning must apply to the presence of a

racial gerrymander because the rationale for the deference

—the importance of local factors—is equally applicable

in both types of cases. As the Court stated in White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. at 769-770, 93 S. Ct. at 2341:

“[W]e are not inclined to overturn these findings,

representing as they do a blend of history and an

intensely local appraisal of the design and impact of

the . . . district in the light of past and present

reality, political and otherwise.”

7

The Gingles court concluded:

“Thus, the application of the clearly erroneous stand

ard to ultimate findings of vote dilution preserves

the benefit of the trial court’s particular familiarity

with the indigenous political reality without endan

gering the rule of law.”

106 S. Ct. at 2752.

A case of minority vote maximization via racial gerry

mandering should be decided under the same standard as

a vote dilution case. District courts possess the critical

knowledge and experience of the local jurisdiction in

issue to make the critical factual determinations on which

these cases must turn.

A finding is only clearly erroneous when “although

there is evidence to support it, the reviewing court on the

entire evidence is left with a definite and firm conviction

that a mistake has been committed.” Anderson v. City

of Bessemer City, N.C., 470 U.S. 564, 573, 105 S. Ct.

1504, 1511 84 L.Ed.2d 518 (1985), (quoting United

States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395

68 S. Ct. 524, 92 L.Ed.2d 746 (1948). Furthermore,

the Court has emphasized that “ ‘[i]n applying the clearly

erroneous standard to the findings of a district court

sitting without a jury, appellate courts must constantly

have in mind that their function is not to decide factual

issues de novo.’ ” Anderson v. City of Bessemer City,

N.C., 470 U.S. 573, 105 S. Ct. 1511 (1985), (quoting

Zenith Radio Corp. v. Hazedtine Research, Inc., 395 U.S.

100, 123, 89 S. Ct. 1562, 23 L.Ed.2d 129 (1969)).

The District Court brought its considerable local knowl

edge to bear in this case; that is readily evidenced by its

exhaustive opinion. That knowledge is an indispensable

ingredient to any sound judgment as to whether this dis

trict so materially departed from Georgia’s traditional and

historical districting principles for racial reasons that it

must stand the test of strict scrutiny.

8

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY HELD, IN

ACCORDANCE WITH SHAW v. RENO, THAT

GEORGIA’S LEGISLATION CREATING THE ELEV

ENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VIOLATED

THE PLAINTIFFS’ RIGHT TO EQUAL PROTEC

TION

Perhaps it is the simplicity of Shaw’s teaching that

creates the problem for Appellants. The District Court’s

summary of Shaw leaves little to quarrel about as to the

standard by which racially gerrymandered districts are to

be judged:

“Shaw holds that if a plaintiff shows that racial con

cerns were the overriding consideration for drafting

a redistricting plan, leading to the creation of dra

matically irregular district boundaries, that plan is

unconstitutional, unless it survives constitutional

strict scrutiny.” See Shaw, 113 S.Ct. at 2826-27.

Contrary to Appellants’ view, Shaw makes clear that

a “highly irregular” boundary line is not the only evidence

that would be probative of the existence of a racial

gerrymander:

“The difficulty of proof, of course, does not mean

that a racial gerrymander, once established should

receive less scrutiny under the Equal Protection

clause than other state legislation classifying citizens

by race. Moreover, it seems clear . . . that proof

sometimes will not be difficult at all. In some excep

tional cases, a reapportionment plan may be so highly

irregular that, on its face, it rationally cannot be

understood as anything other than an effort to ‘seg-

regatfe] . . . voters’ on the basis of race, [cit.]

Gomillion [v. Light foot], 364 U.S. 339, 81 S.Ct.

127 . . . so, too, would be a case in which a state

concentrated a dispersed minority population in a

single district by disregarding traditional districting

principles such as compactness, contiguity and re

spect for political subdivisions.” (Emphasis added).

113 S.Ct. at 2826.

9

No one can dispute the fact that the above-emphasized

portion from Shaw fits the Eleventh District like a glove.

While Georgia has persistently contended the gerryman

der that formed the framework for this district was fash

ioned by the ACLU and forced upon it by the DOJ, those

facts hardly absolve the State from ultimate responsibility.

Appellees agree that the Eleventh District does not

represent a voluntary act of the Georgia legislature. The

District Court made voluminous findings in that regard.

No party disputes those facts. Appellees acknowledge the

State argued mightily against legislatively animating the

gerrymandered version of the “Max-Black” plan that is

now the Eleventh District, because of its blatant violation

of Georgia’s traditional districting principles. (J.S. App.

19). The Georgia Attorney General made this written

statement to the DOJ before finally acquiescing to their

demands:

“. . . [T]he extension of the 2nd District into Bibb

County and the corresponding extension of the 11th

District into Chatham County (Savannah), with

all the necessary attendant changes, violate all reason

able standards of compactness and contiguity.” J.S.

App. 19, emphasis added).2

Given that statement, it is not surprising the State’s

proof as to its adherence to traditional districitng prin

ciples was virtually nonexistent. It would be an under

statement to say that the State’s expert witness on com

pactness, Lisa Handley, was not well received by the

Court. In large measure, this was due to the fact the

only way the State could generate any argument at all on

compactness was to invent a compactness test just for

this district.3 The District Court was not fooled:

2 It is difficult to understand how the Attorney General could now

argue to this Court that the district is compact.

s The District Court found that the “. . . test, formulated . . .

specifically for this litigation, constituted the State’s only notable

submission on the subject of compactness.” (J.S. App. 78)

10

“[T]he . . . test is especially useless in analyzing the

Eleventh District while the vast—and sparsely popu

lated—core of the Eleventh accounts for the district’s

favorable score on Dr. Handley’s test, the narrow—

and densely populated—appendages escape notice.

In fact, this test is an excellent means of highlighting

the egregiously manipulated portions of any voting

districts. . . . (J.S.App. 79, emphasis added).

On the issue of compactness, the District Court found:

“[T]he . . . Eleventh District, from a population

based perspective . . ., is not compact for purposes

of Section 2 of the VRA. The population of the

Eleventh are centered around four discrete widely

spread urban centers that have absolutely nothing

to do with each other, and stretch the district hun

dreds of miles across rural counties and narrow

swamp corridors . . . . These communities are so

far apart that the DOJ’s insistence . . . they are “com

pact” renders the term meaningless. The hooks,

tails and protrusions of those counties reveal the

true “shape” of the district. . . .” (J.S. App. 78-79)4 5

Neither the State nor the Intervenors offered any other

witnesses on the question of the district’s shape. At trial,

Plaintiffs offered the population density map attached as

Appendix 1 to underscore the truth about this district. It

is nothing more than four distant population centers,

gerrymandered to make them majority black, stuck to

gether by over 6000 square miles of farmland. Maps

reevaling the gerrymander of DeKalb, Chatham, Rich

mond and Effingham counties are also included in the

Appendix so the Court can get a feel for just how cleanly

a computer can separate the races. (App. 2-5)®

4 The District Court also found there was considerable potential

for voter confusion due to the fact the “. . . erratic lines and split

counties and precincts do not afford voters ready indications of

the district in which they reside.” (J.S. App. 80, fn. 43)

5 These are known as race maps, the most common tool used by

the DOJ/ACLU to fashion the Eleventh. The orange represents an

11

The State freely admitted race drove the district’s crea

tion and that the ACLU’s Max-Black plan was the DOJ’s

litmus test for the district’s racial population percentages.

Given those admissions, the district had no hope of sur

viving strict scrutiny. So, the State opted for an “all or

nothing” defense by arguing first, that the admitted racial

gerrymandering was accomplished without having to draw

boundaries that were as bizarre as what was done in other

Southern states. Second, the State contended the district

was not bizarre because its boundaries track bits and

pieces of state, county, city, precinct and highway lines.

These arguments, if accepted, would allow wholesale

racial gerrymandering to escape constitutional review.

The District Court made short work of these arguments.

It recognized that the way racial gerrymandering is ac

complished at the Congressional level is to contort distant

densely populated urban areas into super majority black

population centers and then connect them. The urban

cities/counties divided for racial purposes must, by defini

tion, be located on the peripheries of the gerrymandered

district. (J.S. App. 22) This is the only way to segregate

a political subdivision’s population racially. Thus, myriad

chards of the circumferences of these divided cities and

counties always become conterminous with district bound

aries. This is the very evidence from which gerrymander

ing is proven.

The State, however, tried to turn this geographical

truism to their advantage. In its view, bits and pieces of

divided city, county lines that blend with the districts

boundaries because of the gerrymandering taking place

could be considered evidence of regularity. Incredibly, the

tables the State hinges its case on are intended to quantify

just such a contention. (Tables 1-2, Miller, J.S., p. 7-8).

Absurd results would follow if the consequences of

racial gerrymandering were accepted as indicia of regu

area that is over 50% Black; yellow is over 60% Black, and blue

is 35-49% Black. Grey is less than 35% Black. See Plaintiff’s trial

exhibits 11; 18-20.

12

larity. Just two examples should suffice. The State con

tends adherence here and there to State boundaries is evi

dence of a district’s regularity regardless of the location

of the population centers. A review of the unconstitu

tional Fourth District in Louisiana points out the fallacy

of such a contention. Almost half its boundary is cotermi

nous with the State’s northern boundary. See Miller’s

J.S., App. 109. The district itself, however, hangs from

that border like long icicles off a roof, fingers that grope

for and grab pockets of Blacks, but thin out and elongate

to skirt contiguous population centers that are predomi

nantly white. The State would argue that the Court should

not even inquire as to the reasons for the formation of the

“icicles”, given the regularity of the roof line.

For a second example, consider the thin land bridge

that runs through Effingham and Chatham County to

reach the black neighborhoods of Savannah. (App. 3-4)

Its purpose was to get Black people in Savannah into the

Eleventh while maintaining technical contiguity with the

rest of the district. This land bridge has, as its eastern

border, the state line of Georgia and its coast. It has such

a boundary, not because of any desire to follow a state

line, but to avoid the predominantly white population in

Effingham County by running the district to Savannah

partially through a swamp. (J.S. App. 42-43) Should

this racial motive be immune from strict scrutiny merely

because a state line that runs through a swamp came into

play? 8 If ever an argument could be said to put form

over substance, the Appellants have done it.

The District Court correctly refused to ignore the

reason for the unprecedented division of cities and coun- 6

6 Likewise, pieces of the boundaries of DeKalb, Richmond,

Chatham, Wilkes and Baldwin counties that matched the ultimate

boundaries of the Eleventh are touted by the State as proof of the

district’s regularity while, in the same sentence, it freely admits

these counties were torn apart solely to further the segregationist

motives of the district architects.

13

ties required to create the DOJ mandated majority minor

ity districts.7 The majority firmly grasped the fact that the

mechanistic interpretation of Shaw urged by the State

would create a gaping loophole in the fabric of our Con

stitution through which all fashions of admitted racial

gerrymanders would escape strict scrutiny. It did not per

mit this attempted end run around the Equal Protection

Clause.

III. GEORGIA’S UNPRECEDENTED AND EXTREME

DEPARTURE FROM ITS TRADITIONAL DIS

TRICTING PRINCIPLES FOR PURELY RACIAL

REASONS IS SUBJECT TO STRICT SCRUTINY

There is nothing new about this Court’s view that the

Fourteenth Amendment requires strict scrutiny of legisla

tion that incorporates racial classifications. The State’s

“shape only” argument is borne of the fact it cannot allow

an analysis under the strict scrutiny test due to its ac

knowledgement that the District is based on a “black max”

plan—the converse of the “narrow tailoring” required for

the use of racial classifications in legislation. The District

Court made short work of the State’s contention that

shape, and shape alone, must be the evidence from which

a finding of gerrymandering is based:

“Defendants argued . . . that evidence of the legis

lature’s intent to gerrymander must be inferred from

the shape of the . . . District itself, and not from

direct testimony of those involved in the process.

This view finds little support in Shaw v. Reno. The

purpose of scrutinizing a district’s shape is to glean

the intent of the legislature by working backwards.

If the district appears uninfluenced by accepted dis

tricting principles . . . it must have been influenced

7 The District Court also rejected the State’s contention that ad

herence in some spots (the gerrymandered areas) to precinct lines

was evidence of regularity. The State’s own Director of Reappor

tionment Services testified that the use of such lines as racially

motivated. (J.S. App. 46)

14

by unaccepted ones. The Supreme Court explicitly

approved this inferential approach because legisla

tive intent is notoriously difficult—if not logically

impossible—to ascertain . . . . What the Supreme

Court did not do in imbue geography with constitu

tional significance; the requirement for a successful

Equal Protection claim is still intent, however

proved. Foreclosing production of direct evidence

of intent until Plaintiffs convince the Court that a

district looks so weird that race must have dominated

its creation is not what Shaw intended. [Defendants’]

approach would make district shape a (previously

unheard of) threshold to constitutional claims.”

(J.S. App. 42, emphasis added).

In taking up the State’s banner, the dissent has chosen

a path no subsequent court could hope to follow. There

can be no universal standard by which shape, and shape

alone, can govern the ability of citizens to seek relief from

the disenfranchising and discriminatory effects of a racial

gerrymander. Each case is unique to the locale where it

arose. No one would ever suggest for a minute that Black

voters would be so limited that motive and intent could

be ignored in determining whether a gerrymander existed.

That is racism in its purest form and has no place in the

equal protection jurisprudence of this Court.

Of all the three judge courts that have dealt with issue

of racial gerrymandering and construed the standards es

tablished in Shaw v. Reno for constitutional review of an

alleged gerrymander, no court has agreed with the State’s

position. Even in Shaw v. Hunt, where the District Court

rejected the Plaintiffs’ claims in a 2-1 decision, the major

ity refused to adopt such an extremely narrow view of

Shaw. Once that contention is rejected, the State has no

further defenses to offer.

Lest we lose right of it in the smoke and fire of the

racial politics that drove the creation of this district, it is

important to remember that the primary purposes of re

apportionment is to equalize the voting districts’ popula

15

tion so to comply with the constitutional mandate of one

man-one vote. Each state has its own districting tradi

tions, its own history of reapportionment. When those dis

tricting traditions are ignored, when districts are drawn

that twist and turn due solely to the need to meet racial

percentages, the district must stand the test of scrutiny.

That is the only way to insure white voters are not either

being discriminated against, or, if they are, to insure the

State is furthering a compelling state interest in a manner

narrowly tailored to further that interest.

IV. COMPLIANCE WITH THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

CAN NOT CONSTITUTE A COMPELLING GOV

ERNMENTAL INTEREST IN THIS CASE SINCE

THE STATE AFFIRMATIVELY DISAVOWED THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT AS ITS RATIONALE FOR

THE REDISTRICTING LEGISLATION

Unlike the other Southern states defending DOJ man

dated gerrymanders, Georgia did not (because it could

not) argue compliance with the Voting Rights Act as a

compelling state interest to justify this district. It was

wise not to. No court would ever hold the failure to

combine the distant urban centers, skeletonized of their

white citizenry by the computer driven gerrymandering

techniques of the ACLU, would violate Section 2 of the

VRA. The DOJ could never have met the test for vote

dilution laid down by this Court in Gingles, supra. The

District Court so found. (J.S. App. 78-80)

It is not surprising then that the DOJ urged this Court

to great plenary review in the Louisiana case8 and hold

the case at bar. In its jurisdictional statement, the DOJ

carefully skirted the huge problem created by Georgia’s

recognition that compliance with the Voting Rights Act

cannot serve as a compelling state interest to justify the

race based districting that took form as the Eleventh Dis

8 United States v. Hayes, Docket No. 94-558.

16

trict. Note the language the DOJ chose to describe the

dilemma:

“The first question in both [Hayes and this case]

would be whether the State’s asserted interests in

drawing an additional majority minority district

were sufficiently compelling . . . . In both cases,

the primary interests that could be asserted were

the need to comply with Section 2 and . . . Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act . . . (p. 16, emphasis

added).

The key words are “could be asserted.” In this case, it

was not so asserted.

Georgia has gone to great lengths to disavow any cor

relation between the State’s acquiescence on the preclear

ance demands of the DOJ and any perception on the part

of Georgia that the failure to draw such a gerrymandered

district would violate either Section 2 or 5 of the Voting

Rights Act. Georgia had this to say about its preclear

ance experience and what the DOJ believed the Act

required of a state:

“. . . [I]n [the DOJ’s] view . . . anything can be

done in the name of minority voting opportuni

ties. . . . [I]n the interveners’ view . . . ‘race

trumps all else’.” (Miller, J.S., p. 15).

A. A Congressional District Which Is Bizarrely Con

figured And Is Overly Safe From The Vantage

Point Of Assuring The Election Of A Black Repre

sentative, Is Not Narrowly Tailored To Further A

Compelling Governmental Interest

Georgia affirmatively opposed the DOJ’s contention

that the district’s gerrymandered boundaries were com

pelled by the VRA to remedy racially polarized voting.

And Georgia also demonstrated, via expert testimony, that

even assuming a compelling state interest existed in the

VRA, the district was far from being narrowly tailored.

Georgia stood firmly with the plaintiffs on that issue at

17

trial and the District Court agreed. (J.S. App. at pp. 86-

87.)9 Based on testimony offered by the State’s expert

witness, the Court found that Black candidates would

have “. . . an equal chance of being elected in a district

containing 45-50% black registered voters.” (J.S. App.

p. 88) The Eleventh District is overly safe with 57%

Black registered voters which gives the Black candidate

a 73% probability of winning. Obviously, an assessment

using the district’s Black voting age population (61% ),

the standard used by this Court in Johnson v. DeGrandy,

114 S. Ct. 2752 (1994), “. . . would yield an even

higher probability.” J.S. App. 88).

The District Court therefore had little problem finding

that, even assuming the YRA provided a compelling state

interest to engage in remedial districting, the district was

not narrowly tailored. Georgia thus found itself vindi

cated on the one hand, but devoid of any constitutional

basis upon which to justify the race based districting that

resulted from Georgia’s acquiescence to the DOJ/ACLU

ultimatum to “maximize” Black voting strength, regard

less of the bizarre shape of the resulting district, or be

denied clearance under the VRA.

The consequences of the DOJ’s Section 5 review of

the Georgia Congressional plan, if left to stand, would

have cataclysmic effects on the democratic form of gov

ernment we are guaranteed by our Constitution. In the

Eleventh District, regional representation has been sup

planted by racial representation. To tinker with such

a fundamental aspect of our democracy would be un

thinkable but for the fact its proponents advance their

claim under the banner of “equal opportunity”. The road

to a color blind society is surely not followed by method- 9

9 The District Court correctly observed that . . the State . . .

retained Dr. Katz for the unusual purpose of undermining the

testimony of both Intervenor United States’ expert . . . and

Plaintiffs’ expei't. He was largely successful.” (J.S. App. 86)

18

ical segregation of the races into separate voting districts.

The Constitution must remain unsullied in its pristine

guarantee of equal protection if we are not to regress

into a country of racial and ethnic enclaves. This Court

has made this point time and time again. See e.g., Wright

v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52, 53-58, 84 S. Ct. 603 (1964).

The District Court correctly implemented that message

in this case. (J.S. App. 32, n.17)

V. GEORGIA CANNOT HAVE A COMPELLING GOV

ERNMENTAL INTEREST IN PROPORTIONAL

REPRESENTATION OF MINORITIES

This case was foreshadowed in Justice Kennedy’s con

curring opinion last term in Johnson v. DcGrandy, 114

S. Ct. 2647, 2666 (1994).

“Operating under the constraints of a statutory re

gime in which proportionality has some relevance,

States might consider it lawful and proper to act with

the explicit goal of creating a proportional number of

majority-minority districts in an effort to avoid Sec

tion 2 litigation. . . . The Department of Justice

might require (in effect) the same as a condition

to granting preclearance under Section 5 of the

Act. . . . Those governmental actions, in my view,

tend to entrench the very practices and stereotypes

the Equal Protection Clause its set against, [cit.]

As a general matter, the sorting of persons with

any interest to divide by reason of race presents

the most serious constitutional questions.” Opinion

at pp. 20-22.

Justice Kennedy’s fears became reality in Georgia.

After the DeGrandy decision was handed down, the

State announced that its alleged interest in “proportion

ality” would, standing alone, satisfy the troublesome need

for a compelling state interest. (J.S. App. 51) This novel

contention, borne of a most tortured reading of the

Court’s DeGrandy opinion, was juxtaposed against the

19

explicit disavowel in the VRA of any requirement of pro

portional representation and summarily dismissed by the

District Court. (J.S. App. 53-54)

The State argues that the end (rough proportional

ity) somehow justifies the means (segregation via gerry

mander). The District Court characterized the State’s

argument as tautological, holding proportionality standing

alone, can never be a compelling state interest. (J.S. App.

53) To require proportionality is to sanction racial quotas.

The constitution forbids it, and the Voting Rights Act

specifically disavows it. To accept the State’s claim that

proportionality, in these circumstances, does not function

as a racial quota, would require this Court to ignore the

overwhelming and largely undisputed evidence to the con

trary detailed in the District Court’s opinion regarding

the origins of the Georgia plan. To evaluate proportional

ity to such a level would require reversal of a long line

of precedent that prohibits employment of racial quotas

by governments, from admissions policies for professional

schools, to public sector affirmative action plans and the

awarding of public contracts. See e.g., City of Richmond

v. /. A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469, 109 S. Ct. 706, 102

L. Ed. 2d 854 (1989) (plurality opinion); Regents of

University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 98 S. Ct.

2733, 57 L. Ed. 2d 750 (1978).

The evidence was overwhelming on the issue. The

Eleventh District’s boundaries were drawn specifically to

maximize the number of minority controlled districts and

to meet “Black-Max” racial population quotas. Not even

Appellants contend that the district’s bizarre shape was

an incidental and natural development during reappor

tionment. The number of majority minority districts in

the plan suddenly became proportionate to the percentage

of black people living in the State only because the DOJ

decreed it be so over the State’s strident objection. The

State’s eleventh hour attempt to reply on proportionality

20

is an attempted revision borne out of advocacy rather than

history.

If there were sufficiently large, concentrated and com

pact minority populations capable of supporting the cre

ation of three minority controlled districts, Section 2 of

the VRA would have provided the mandate for their

creation. See Gingles, supra. That was not the case

here, the District Court finding “. . . the district does not

satisfy the Gingles preconditions . . .”. J.S. App. 88)

Were it otherwise, there would be no need for any dis

cussion of proportionality in the context of what com

pelling state interest could justify the race based district

ing under challenge. The State correctly conceded it did

not possess the kinds of contiguous and concentrated

minority populations sufficient to justify, or even mandate,

the creation of three minority districts under the Gingles

standard. With this concession, the VRA falls away as

substantiation for the blatant dominance of race as the

creative force behind the Eleventh District.

The State acknowledged there is no legal obligation or

authority under the VRA to excise the black people out

of DeKalb County and link them by various land bridges

to distant black populations excised out of coastal Savan

nah. In fact, the State stipulated Savannah would not

have been included in the District but for the need to

increase the Black population of the District. (J.S. App.

48-49)10 The ideal of proportionality can never justify

a State’s creation of voting districts based on race with

quota like black population percentages imposed by the

DOJ/ACLU. This Court must leave this social debate

without arming proponents of proportionality with con

10 Incredibly, the line drawing in Chatham County (Savannah)

excised a 80,000 plus population for inclusion in the Eleventh that

was 84% Black from a general population that was 62% white.

See Race Map of Chatham County at App. 2.

stitutional authority to gerrymander. Given the standard

of review applicable to this case, this Court must accept

the District Court’s findings on this issue and affirm the

decision below.

VI. THE ABRAMS INTERVENORS SHOULD NOT BE

PERMITTED TO PARTICIPATE IN ANY PLENARY

REVIEW OF THIS CASE

From the onset, this litigation has been slowed and

unduly complicated by the presence of the Intervenors.11

That sentiment is borne out by a review of the ACLU’s

jurisdictional statement. Their contentions at trial and

on appeal are wholly duplicative of the DOJs position.

The ACLU intervenors present no credible arguments or

contentions not adequately advanced either by Georgia

or the Justice Department.12 Should this Court not sum

marily affirm the judgment below, they are not a neces

sary party to any plenary review of this case. For this

reason, the six (6) issues they urge the Court to consider

are dealt with summarily below:

1. Plaintiffs lack of standing: The three judge Court

characterized the lack of standing argument as frivolous.

(Order of June 14, 1994). Shaw specifically states that

nothing in the law precludes “white voters (or voters of

any race) from bringing a . . . claim that a reappor

tionment plan rationally cannot be understood as anything

other than an effort to segregate citizens into separate

voting districts on the basis of race without sufficient jus

tification.” 113 S. Ct. at 2824, 2830. No Court has

11 During the trial of this case, the Court expressed constant

displeasure over the role Intervenors sought to play in the presenta

tion of the evidence. The Court’s frustration reached the point

where Judge Edenfield observed that, in retrospect, granting the

Intervenors party status was a mistake.

1:2 All DOJ/ACLU evidence at trial was presented jointly. The

ACLU offered no independent expert testimony.

22

since questioned Shaw’s holding that voters having stand

ing to challenge racially gerrymandered districts. The

argument is not worthy of further discussion; perhaps

that is why the ACLU Interveners only offered two sen

tences on the subject.

2. The District is not bizarre: The Court below found

the district’s boundaries to be bizarre as that term is de

fined in Shaw. The standard of review of such fact finding

makes it unworthy of plenary review. The ACLU inter-

venors offered no independent evidence as to the appear

ance of the district. Instead, they focused their presenta

tion on the proposition, which no court has accepted to

date, that being Black, in and of itself, creates a racial

community of interest that transcends geography and le

gitimizes majority minority districts, no matter how

bizarre their shape. Again, the argument is not a serious

one given the Court’s holding in Shaw.

3. Racial Community of Interest As Compelling State

Interest: As noted above, the question is not substantial.

The racial community of interest argument advanced by

these intervenors would effectively overrule Shaw. The

consolidation of Black voters into their own districts so

to maximize their voting strength, regardless of the geo

graphic aberrations required to bring together a “racial”

community of interest, is the political apartheid Shaw

speaks so eloquently against. In the search for an in

tegrated color blind society, the ACLU intervenors advo

cate resurrection of racial enclaves that, at least politi

cally,, will resegregate society. That is precisely what

Shaw was intended to prevent.

4-5. Voting Rights as a Compelling State Interest:

Throughout the case, the State has refused to raise the

VRA as a compelling state interest to justify the bizarre

geography of the Eleventh District. The State put on

expert testimony, accepted by the Court, rebutting In

tervenors’ joint efforts to paint Georgia as suffering from

rampant racially polarized voting that mandated con

23

struction of a remedial district. Intervenors’ frustration

with the State’s rejection of this defense has found a voice

in their decision to vicariously advance compliance with

the VRA as the State’s motive for the district’s con

figuration. The missing link in the logic is, of course,

the State’s refusal to participate in the plan and the incur

able antagonism between the maximization goals that the

district was based on and the narrow tailoring required

under strict scrutiny. The Intervenors are left with the

State’s post hoc rationalization, borne of its misreading

of the DeGrandy decision, that proportionality was its

“true motive”. However, this is not simply a compelling

state interest sufficient to withstand strict scrutiny under

the Equal Protection Clause. With that recognition, the

equal protection analysis is at an end.

6. Narrow Tailoring: The issue is mooted from the

State’s vantage point due: (1) to the absence of a com

pelling state interest; and (2) the expert testimony it

offered to rebut the Intervenors’ claim that the 65%

Black population was needed to give minority candidates

an equal opportunity. Intervenors are hard pressed to

contend with any credibility that a plan known as the

“Black Max” is “narrowly tailored”. The District Court

meticulously traced the interrelationship between the ad

vocacy of the ACLU, the positions taken by the DOJ

during the preclearance process of the fact the ACLU’s

Black-Max plan became the blueprint for what is, for

now, the Eleventh District. Maximization is the antithesis

of narrow tailoring. The ACLU is “hoisted on its own

pitard” with respect to this aspect of the strict scrutiny

test.

24

CONCLUSION

This case presents a scenario that is an anathema to a

constitutional democracy. The will of the people, as ex

pressed by their elected representatives, was subverted in

ruthless fashion. And this subversion was accomplished

by no less a force than the United States Department of

Justice, whose conduct the District Court characterized

as nothing less than an “embarrassment.” (J.S. App. 27)

Democracy is a system of government that depends on

an intricate scheme of checks and balances for its viability.

The genius of our democracy is that there is a check to

correct every wrong—even when it is visited upon the

people by the federal agency charged with enforcement of

our constitution and laws. The trial court performed that

function thoroughly and courageously.

This Court has repeatedly acknowledged the extreme

deference due local tribunals in matters of this nature. It

should not stray from that precedent, particularly where

it is not presented with a single issue of first impression

by this case due, in large measure, to the State’s admis

sions and its refusal to rely upon the Voting Rights Act

as justification for the gerrymander. Instead, Georgia has

offered the weak pop fly of proportionality as its reason

for deployment of a racial gerrymander. That is not an

argument worthy of serious consideration.

Racial gerrymanders that torture our most fundamental

right—to vote in elections free of governmental interven

tion on the side of any candidate or any class of candi

dates—are generally not welcome in a democracy. Given

the well supported and largely stipulated findings upon

which the District Court decision is based, coupled with

the deference they are due, summary affirmance is war

ranted.

25

Respectfully submitted,

A. Lee Parks

Counsel of Record

Larry H. Chesin

Kirwan, Goger, Chesin

& Parks, P.C.

75 Fourteenth Street

2600 The Grand

Atlanta, Georgia 30309

(404) 873-8000

Attorneys for

December, 1994 Movants-Appellees

Persons per Acre by Census Block Group

APPENDIX I

Client : CONGRESS

Plan : C1992

Type : Congressional

Reapportionment Services Office

Suite 407, Legislative Office Bldg

? O )

‘-A L

>

Georgia General Assembly

A

PPEN

D

IX

2

Client : CONGRESS

Plan : C1992

Type : Congressional

B R Y A N

Georgia Genera! Assembly

A

PPEN

D

IX

Client

Plan

Type

CONGRESS

C1992 APPENDIX 4

Congressional

A

PPEN

D

IX

5