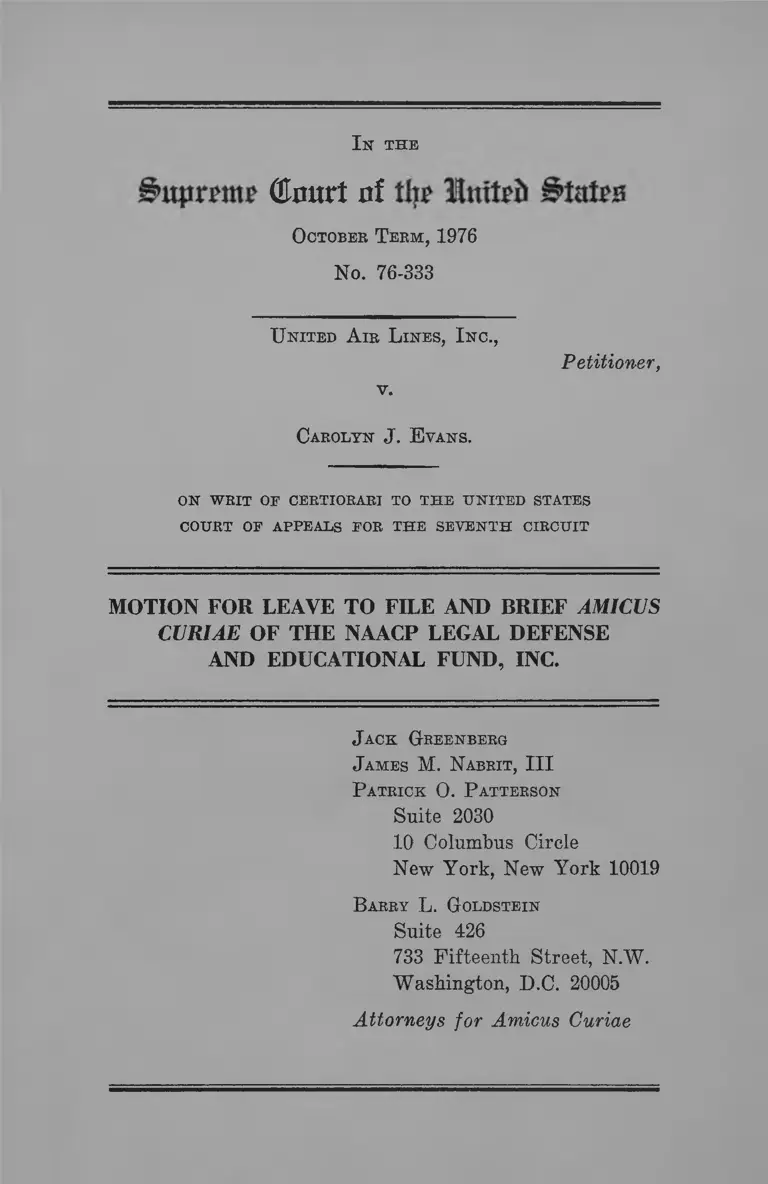

United Air Lines v. Evans Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United Air Lines v. Evans Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1976. 85d93a21-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a844a0b3-49b7-4709-8fdd-85e787448e50/united-air-lines-v-evans-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

©curt of

OcTOBEB T e e m , 1976

No. 76-333

U n it e d A ie L in e s , I n c .,

V .

C aeolyn J . E v a n s .

Petitioner,

ON WEIT OF CEETIOEAEI TO THE UNITED STATES

COUET OF APPEALS FOE THE SEVENTH CIECUIT

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF AMICUS

CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

J ack Ghbenbeeg

J am es M. N abeit , II I

P ateick 0 . P atteeson

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

B aeey L. G oldstein

Suite 426

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

I n’ t h e

(Unurl of t!|o i>tatoB

OcTOBEB T e e m , 1976

No. 76-333

U n it e d A ie L in e s , I n c .,

Petitioner,

Caeolyn J . E v a n s .

ON WEIT OE CBETIOEAEI TO THE UNITED STATES

COUET OE APPEALS EOE THE SEVENTH CIECUIT

STATEMENT OF INTEREST AND

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

hereby moves for leave to file the attached brief as amicus

curiae.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a non-profit corporation incorporated under the

laws of the State of New York. It was formed to assist

black persons in securing their constitutional rights by the

prosecution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its pur

poses include rendering legal services gratuitously to

Negroes suffering injustice by reason of racial discrimi

nation. For many years attorneys of the Legal Defense

Fund have represented parties in employment discrimina

tion litigation before this Court and the lower courts. The

Legal Defense Fund believes that its experience in em

ployment discrimination litigation may be of assistance to

tlie Court. Consent to the filing of this brief has been

granted by counsel for respondent but refused by counsel

for petitioner. The proposed brief is submitted in support

of respondent though advancing reasons somewhat dif

ferent than those relied on by the court below and by

respondent.

W h ee e fo bb , the NAACP Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc., respectfully prays that this motion be

granted, and that the attached brief be filed.

J ack Geeenbeeg

J am es M. N abeit , II I

P ateick 0 . P atteeson

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

B aeey L. G o ldstein

Suite 426

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

IlT THE

Qlourl nf tI|F i>latrB

O ctober T erm , 1976

No. 76-333

U n ited A ir L in e s , I n c .,

Petitioner,

Carolyn J . E v a n s .

ON WRIT OE certiorari TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OE APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

ARGUMENT

This case concerns the circumstances in which the cur

rent application to an individual employee of a seniority

policy which is facially neutral, but which perpetuates the

effects of past discrimination against that employee, may

he held to constitute a continuing violation of Title VII

of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, as amended by the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

et seq. Although petitioner’s brief discusses at some length

the statutorily prescribed time periods for filing a charge

of discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission,^ this requirement does not appear to be at

issue here; because the respondent did not file such a

̂Prior to 1972, former section 706(d) of Title VII provided in

pertinent part that a charge “shall be filed within ninety days

after the alleged unlawful employment practice occurred.” Sec

tion 706(e), as amended in 1972, extended this period to 180 days.

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(e).

charge within the applicable ninety-day time limit after

the concededly unlawful ̂ termination of her employment

in 1968, she is forever barred from obtaining the full Title

V II relief to which she would otherwise have been entitled

solely as a remedy for that unlawful act. The respondent

here does not seek such a remedy, but rather seeks relief

from the perpetuation of the effects of the prior unlawful

termination which she has suffered on a continuing basis

since her re-employment by the petitioner in 1972. The

issue presented by this case, then, is a narrow one: Where

an employee who has been the victim of a discriminatory

hut previously unchallenged termination is subsequently

rehired by the same employer, does the current and con

tinuing denial of the rehired employee’s previously accrued

seniority rights constitute an unlawful employment prac

tice within the meaning of Title VII?

The language of the statute indicates that this ongoing

deprivation of rights is a violation. Section 703(a) not

only declares that it is in general unlawful “to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or privileges of employment . . .,” ® hut

goes on to specify that it is unlawful for an employer

to limit, segregate, or classify his employees or appli

cants for employment in any way which would deprive

or tend to deprive any individual of employment op

portunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as

an employee, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.^

An employer who, like the petitioner here, discharges

employees because of their sex, and then later rehires them

on the condition that they continue to he deprived of the

̂ Evans’ emplojinent was terminated in 1968 in accordance with

United’s “no-marriage” rule for stewardesses, which was held to

violate Title VII in Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d

1194 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 991 (1971).

H 2 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a)(l).

<42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a)(2).

seniority rights which were unlawfully taken from them in

the past, is clearly engaged in an ongoing practice which

violates this explicit language. Any construction of Title

Vll which might immunize such conduct from liability

would be contrary to the statutory language and would

frustrate the congressional intent “to prohibit all prac

tices in whatever form which create inequality in employ

ment opportunity due to discrimination on the basis of

race, religion, sex, or national origin . . . ” Franks v. Bow

man Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763 (1976).

The legislative history of the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Act of 1972 supports the plain meaning of the stat

utory language and demonstrates beyond dispute that

Congress intended to prohibit not only individual acts of

discrimination, but also policies which perpetuate the ef

fects of past acts of discrimination. As the Senate Com

mittee on Labor and Public Welfare recognized in its

report:

Employment discrimination as viewed today is a . . .

complex and pervasive phenomenon. Experts familiar

with the subject now generally describe the problem

in terms of “systems” and “effects” rather than sim

ply intentional wrongs, and the literature on the sub

ject is replete with discussions of, for example, the

mechanics of seniority and lines of progression, per

petuation of the present effect of pre-act discrimina

tory practices through various institutional devices,

and testing and validation requirements.®

The congressional intent to prohibit continuing violations

is clearly manifested in the language of section 706(g),

which was amended in 1972 to provide that “ [b]ack pay

liability shall not accrue from a date more than two years

prior to the filing of a charge with the Commission.” 42

U.S.C. §2000e-5(g). This provision can have no meaning

® S.Eep. No. 415, 92d Cong, 1st Sess, 5 (1971), quoted in Franks

V. Bowman Transportation Co., supra at 765 n.21.

except in the context of a continuing violation which has

been occurring over a period far in excess of the 180-day

time limit for the filing of a charge prescribed by section

706(e). Within that context it is clear that, although hack

pay liability is limited, the continuing violation of Title VII

is itself an unlawful employment practice which is subject

to challenge before the EEOC and in the courts.

The implicit meaning of the back pay limitation con

tained in section 706(g) was made explicit in the congres

sional section-by-section analysis of the 1972 Act.® With

reference to the time limits for the filing of charges, the

analysis stated as follows:

This subsection as amended [section 706(e)] pro

vides that charges be filed within 180 days of the

alleged unlawful employment practice. Court decisions

under the present law [former section 706(d)] have

shown an inclination to interpret this time limitation

so as to give the aggrieved person the maximum bene

fit of the law; it is not intended that such court deci

sions should be in any way circumscribed by the time

limitations in this subsection. Existing case law which

has determined that certain types of violations are

continuing in nature, thereby measuring the running

of the required time period from the last occurrence

of the discrimination and not from the first occurrence

is continued, and other interpretations of the courts

maximizing the coverage of the law are not affected.''

Thus, it is clear from the statutory language and from

the legislative history that Congress intended to outlaw

® The section-by-section analysis was prepared by the Senate co

sponsors of the Act, Senators Williams and davits. Senator Wil

liams introduced it as “an analysis of H.E. 1746 as reported from

the Conference. . . .” 118 Cong. Rec. 7166 (1972). The identical

section-by-section analysis was introduced into the House record by

Representative Perkins, 118 Cong. Rec. 7563 (1972). The Con

ference Committee bill was accepted by both chambers. Id. at

7170, 7573.

’ 118 Cong. Rec. 7167, 7565 (1972).

present, continuing practices whicli perpetuate the effects

of past discrimination, and that Congress intended to

grant aggrieved persons the right to file charges with

the EEOC—and subsequently to obtain relief from the

courts—at any time during the continuing occurrence of

such practices. Even in cases which have held that such a

continuing violation is not established merely by the con

tinuing nonemployment of a terminated former employee,*

the courts have acknowledged that Title V II provides “a

remedy for past actions Avhich operate to discriminate

against the complainant at the present time,” and that this

remedy may be available to present employees, including

those on layoff status.® Olson v. Rembrandt Printing Co.,

511 F.2d 1228, 1234 (8th Cir. 1975) {en banc); Terry v.

Bridgeport Brass Co., 519 F.2d 806, 808 (7th Cir. 1975).

Compare Collins v. United Air Lines, Inc., 514 F.2d 594,

596 (9th Cir. 1975), with Gibson v. Local 40, Super-

* In Electrical Workers Local 790 v. Bobbins & Myers, Inc., 45

U.S.L.W. 4068 (U.S. Dec. 20, 1976), this Court rejected a claim

that the statutory period for filing a charge alleging a discrim

inatory termination could begin to run from the date of the con

clusion of grievance-arbitration procedures, rather than from the

date of the termination. That decision is not dispositive of the

instant case. There both the parties and the courts below had

assumed throughout the proceedings that the discharge was the

significant occurrence, id. at 4069, whereas here the dispute has

been focused from the beginning on the continuing denial of se

niority. Moreovor, in Electrical Workers the Court specifically

noted that a different result might obtain if the terminated em

ployee were reinstated, id., which is precisely the case here. Finally,

in Electrical Workers the Court found no express legislative his

tory indicating the intent of Congress with respect to the effect

of grievance procedures on Title VII time limits, but here there

are explicit legislative materials demonstrating that Congress in

tended to permit the filing of a charge at any time during the

ongoing occurrence of a continuing violation.

® Even petitioner concedes that a continuing violation may exist

where there is an “ongoing seniority or other policy that properly

can be said to have had its genesis in the original discriminatory

practice or that was or is so inexorably tied to the former discrim

inatory practice as to represent merely a present extension of it.”

Brief for Petitioner, at 21. Amiens submits that this is just such

a ease.

cargoes <& Checkers, 13 F E P Cases 997, 1004 (9tli Cir.

1976).^“ The issue here is whether and to what extent the

continuing violation concept applies to a case such as

this, where a four year hiatus in the employment relation

ship has preceded the renewal of that relationship and the

commencement of the continuing consequences of the past

discrimination.

No prior decision of this Court directly controls the

resolution of this question. The Court in Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971), found that under Title

VII, practices which are “neutral on their face, and even

neutral in terms of intent, cannot be maintained if they

operate to ‘freeze’ the status quo of prior discriminatory

employment practices.” Id. at 430. But the Court was not

there confronted with any question as to the continuing

nature of any unlawful practice or as to whether a charge

had been timely filed in relation to the violation alleged.

In Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 IJ.S. 747

(1976), the Court held that constructive seniority is ordi

narily required as part of the Title V II remedy for dis

crimination in hiring, hut the Court did not explicitly

decide whether the continuing denial of seniority rights

stemming from such past discrimination is itself an unlaw

ful practice, nor did the Court have any occasion to con

sider the point at which a charge must be filed during the

continuing occurrence of such a practice.

Nevertheless, the principles underlying these decisions

are, as the court below recognized, clearly relevant to the

question presented here. In every circuit which has

Petitioner contends that there is a conflict between the Ninth

Circuit’s decision in Collins and the Seventh Circuit’s decision in

the instant case. The absence of any such conflict is conclusively

demonstrated by the Ninth Circuit’s specific reliance on the deci

sion of the court below in support of its conclusion in Oibson that

a continuing seniority preference in union work referrals “per

petrated the effects of past discriminatory practices and constituted

a present violation of Title VII.” 13 PEP Cases at 1004 and n.20.

See Kennan v. Pan American World Airways, Inc., 13 PEP Cases

1530, 1533 (N.D. Cal. 1976).

resolved the matter, the courts have found that facially

neutral seniority practices which “freeze the status quo,”

preventing the victims of past discrimination from attain

ing their rightful place in the employment hierarchy, are

themselves unlawful under Title Vlld^ This Court’s deci

sion in Franks clearly supports this conclusion. There the

Court found that Title V II “ ‘requires that persons ag

grieved by the consequences and effects of the unlawful

employment practice be, so far as possible, restored to a

position where they would have been were it not for the

unlawful discrimination’.” 424 U.S. at 764. The Court also

recognized in Franks that, due to the ongoing nature and

effect of seniority practices, the reform of those practices

“cuts to the very heart of Title V II’s primary objective of

eradicating present and future discrimination . . . .” Id. at

768 n.28.

Thus, the Griggs and Franks decisions clearly indicate

that a continuing seniority policy which perpetuates the

effects of past discrimination against present employees

is itself a violation of Title VII. Amicus submits that

such a policy is unlawful not only as to persons continu

ously employed since the date of the first discriminatory

act against them, but also as to persons who have been

discriminatorily terminated and later rehired without their

previously accrued seniority. A person in this latter group,

in contrast to one who is unlawfully discharged and who

thereafter has no further contact with the former em-

See Acha v. Beame, 531 F.2d 648 (2d Cir. 1976); United

States V. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d Cir. 1970) ;

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.), cert, dis

missed, 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 539

F.2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976) ; United States v. Papermakers Local 189,

416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ;

EEOC V. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir.), cert, filed,

44 U.S.L.W. 3214 (U.S. Oct. 7, 1975) ; Rogers v. International

Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 (8th Cir.), as modified, 526 F.2d 722

(1975) ; United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th

Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ; Jones v. Lee Way

Motor Freight, 431 F.2d 245 (10th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401

U.S. 954 (1971).

8

ployer, is subjected to a renewal and an atSrmative per

petuation of the effects of the original discriminatory ter

mination. I t is this active transmission of the effects of

the past unlawful act into the present and future which

constitutes a continuing violation of Title VII. Kennan

V . Pan American World Airways, Inc., 13 FE P Cases 1530,

1531-34 (N.D. Cal. 1976).

The application of the continuing violation concept to

cases such as this does not impose on employers an affirma

tive duty to reinstate all discriminatorily terminated em

ployees. A discharge followed hy continuing non-employ

ment, and even hy a refusal to rehire which is not based

on the discharge, does not constitute a continuing violation

of Title V II; a charge of discrimination must be timely

filed with relation to the date of discharge. Collins v.

United A ir Lines, Inc., supra. However, it is clear that a

refusal to rehire which is based on the prior unlawful dis

charge is an act which renews the past discrimination and

which constitutes a present violation of Title VTI. See

Stroud V . Delta Airlines, Inc., 392 F.Supp. 1184, 1189, 1193

(N.D. Ga. 1975).^ ̂ Similarly, the act of reinstatement

without previously earned seniority, and the continuing

denial of that seniority thereafter, constitute an active

renewal and perpetuation of the past illegality. These

affirmative acts and practices are continuing violations of

Title V II; mere continuing nonemplojmient following an

unlawful discharge is not.

The decision of the court below does not eliminate the

period of limitations for Title "̂ HI actions, nor does it

permit employees to resurrect time-barred claims. Where,

as here, an employee has been terminated and has failed

to file a charge of discrimination within the statutory

Thus, contrary to petitioner’s suggestion, an affirmance here

would not encourage employers to adopt a policy of refusing to

rehire discriminatorily terminated former employees. Such a policy

would be unlawful whether or not the continuing violation concept

applies to the facts of the instant case.

period following her termination, she has irretrievably

lost her right to obtain reinstatement, back pay, and other

relief to which she would have been entitled solely as a

remedy for the unlawful termination. The subsequent

renewal and perpetuation of the effects of that past dis

crimination did not remove the bar to her old claim; she

has lost the back pay and other compensation and bene

fits which she could have obtained had she filed a timely

charge following her termination in 1968. But, since her

reemployment in 1972, she has been subjected to an active

and continuing denial of her Title V II rights, and this

denial gives rise to a new claim for relief which clearly

is not barred by time. Although she cannot now recover

the full remedy which she could have obtained for her

unlawful termination had she filed a timely charge in 1968,

she is entitled to relief for the present, continuing viola

tion which has been occurring since her reemployment

without seniority in 1972.̂ ®

The decision of the court below correctly recognizes

that the continuing, affirmative perpetuation of the effects

of past discrimination is itself a violation of Title VII.

The statutory language, the legislative history, and the

prior decisions of this Court under Title V II fully support

this conclusion. Even as an employer modifies or elimi

nates a discriminatory policy which it has pursued in the

past, it must also look to the future and review and adjust

its seniority and other continuing practices to insure that

the consequences of its past discrimination will not operate

Similarly, in the hypothetical examples posed in the Brief for

Petitioner, at 19, the employees may be barred from recovering

the full relief to which they would have been entitled had they

filed charges within the statutory period following the original

unlawful act, but they are not barred from obtaining a remedy for

the present operation of practices which have perpetuated the

effects of this original discrimination for thirty years. As noted

above, the employer’s back pay liability would be limited to that

accruing no more than two years prior to the filing of such a

charge. 42 U.8.C. § 2000e-5fg). Thnsj the hypothetical employees

would have irretrievably lost twenty-eight years of back pay.

10

indefinitely to deprive its victims of their rightful place

in the employment hierarchy. While employers should not

be required, and are not required by the decision in this

case, to answer to time-barred claims of past discrimina

tion, the remedial purposes of Title V II mandate that em

ployers he held accountable for their present practices

which perpetuate inequality in employment opportunity

due to discrimination.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, this Court is urged to

afiSrm the decision of the court of appeals.

Respectfully submitted.

J ack Geeek beeg

J am es M. N abeit , II I

P ateick 0 . P attbeson

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

B aeey L. G o ldstein

Suite 426

733 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

MEIIEN PRESS INC — N. Y. C 219