Vulcan Society v. Bloomberg Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Affirming Judgement in Favor of Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 13, 2012

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Vulcan Society v. Bloomberg Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Affirming Judgement in Favor of Appellees, 2012. adec9b22-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/a89657cc-10fb-49d5-9b1b-9e0fa93691c4/vulcan-society-v-bloomberg-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-affirming-judgement-in-favor-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

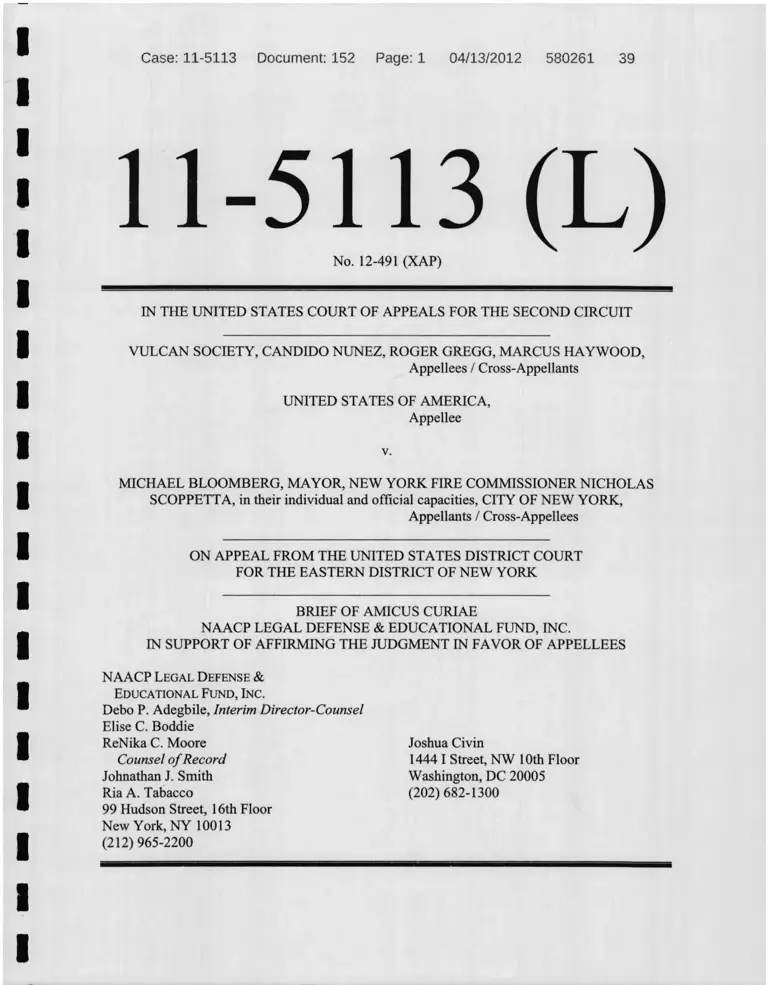

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 1 04/13/2012 580261 39

11-5113 (L)

No. 12-491 (XAP)

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

VULCAN SOCIETY, CANDIDO NUNEZ, ROGER GREGG, MARCUS HAYWOOD,

Appellees / Cross-Appellants

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

v.

MICHAEL BLOOMBERG, MAYOR, NEW YORK FIRE COMMISSIONER NICHOLAS

SCOPPETTA, in their individual and official capacities, CITY OF NEW YORK,

Appellants / Cross-Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF AFFIRMING THE JUDGMENT IN FAVOR OF APPELLEES

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

Debo P. Adegbile, Interim Director-Counsel

Elise C. Boddie

ReNika C. Moore

Counsel of Record

Johnathan J. Smith

Ria A. Tabacco

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Joshua Civin

1444 I Street, NW 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 2 04/13/2012 580261 39

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Authorities................................................................................................ iii

Interest of Amicus Curiae.........................................................................................1

Summary of the Argument....................................................................................... 2

Argument.................................................................................................................. 6

I. Entrenched discrimination in firefighting was a key factor that

prompted Congress to extend Title VII to public employers in 1972........... 6

A. In 1972, Congress found rampant exclusion of African

Americans from fire departments nationwide.....................................6

B. Racial exclusion in the FDNY was severe prior to the 1972 Act

and has persisted................................................................................. 10

II. Title VII vests courts with wide latitude to exercise their equitable

powers to address disparate-impact discrimination.................................... 12

A. The plain language and legislative history of Title VII establish

Congress’s intent to provide courts with broad authority to

remedy employment discrimination in all forms.............................. 14

B. Section 706(g) authorizes, and courts frequently impose,

affirmative relief to remedy disparate-impact violations................. 19

C. Any limitations on affirmative relief apply only to long-term

quotas for hiring or other individualized job benefits awarded

based on race......................................................................................22

III. The limited award of affirmative relief was not an abuse of discretion.....25

A. The “persistent or egregious” standard does not apply......................25

B. In any event, the FDNY’s discrimination was persistent and

egregious............................................................................................28

Conclusion..............................................................................................................29

i

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 3 04/13/2012 580261 39

Certificate of Compliance.....................................................................................31

Certificate of Service............................................................................................32

ii

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 4 04/13/2012 580261 39

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975)........................... 1, 15, 17, 19

Association Against Discrimination in Employment, Inc. v. City o f

Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256 (2d Cir. 1981)......................................... 13, 19, 20, 28

Berkman v. City o f New York, 812 F.2d 52 (2d Cir. 1987)..................................... 24

Berkman v. City o f New York, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1983)...........................passim

Bradley v. City o f Lynn, 443 F. Supp. 2d 145 (D. Mass. 2006).............................. 12

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)................................................. 8

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982)................................................................ 8

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank o f Richmond, 467 U.S. 867 (1984)...................... 2

Dozier v. Chupka, 395 F. Supp. 836 (S.D. Ohio 1975).......................................... 22

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984).......................... 1

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976).................... 1, 15, 16

Garcia v. Lawn, 805 F.2d 1400 (9th Cir. 1986) .................................................... 16

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).................................... 1,2, 17, 29

Guardians Association o f New York City Police Department, Inc. v.

Civil Service Commission, 630 F.2d 79 (2d Cir. 1980)................... 23, 24, 25, 28

Hammon v. Barry, 813 F.2d 412 (D.C. Cir. 1987).................................................. 9

Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973)................................................... 8

Harper v. Mayor & City Council o f Baltimore, 359 F. Supp. 1187

(D. Md. 1973)........................................................................................................ 8

Harrison v. Lewis, 559 F. Supp. 943 (D.D.C. 1983).............................................. 22

Honadle v. University o f Vermont & State Agricultural College,

56 F. Supp. 2d 419 (D. Vt. 1999)...........

iii

26

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 5 04/13/2012 580261 39

Hutchison v. Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., 647 F.3d 479 (2d Cir.

2011)...................................................................................................................... 5

In re Employment Discrimination Litigation Against Alabama,

198 F.3d 1305 (11th Cir. 1999).................................................................... 13,20

International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324(1977).............................................................................................................15

Kirkland v. New York State Department o f Correctional Services,

520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975)......................................................................... 24, 25

Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 130 S. Ct. 2191 (2010).....................................................1

Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 643 F.3d 201 (7th Cir. 2011)..........................................12

Local 28 o f Sheet Metal Workers ’ International Association v. EEOC,

478 U.S. 421 (1986).....................................................................................passim

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United States,

416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969)............................................................................... 21

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)..................................................... 17

McNamara v. City o f Chicago, 138 F.3d 1219 (7th Cir. 1998).................................8

McNamara v. City o f Chicago, 959 F. Supp. 870 (N.D. 111. 1997)............................8

Mems v. City o f St. Paul, Department o f Fire & Safety Services,

327 F.3d 771 (8th Cir. 2003)................................................................................. 9

NAACP v. Town o f East Haven, 259 F.3d 113 (2d Cir. 2001)...............................21

Newark Branch, NAACP v. Town o f Harrison, 940 F.2d 792 (3d Cir.

1991)...............................................................................................................13,21

Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District

No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007).................................................................................. 26

Pollard v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 532 U.S. 843 (2001)..........................18

Republic Steel Corp. v. NLRB, 311 U.S. 7 (1940).................................................. 16

Ricci v. DeStefano, 129 S. Ct. 2658 (2009)............................................................ 27

IV

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 6 04/13/2012 580261 39

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters Local 638 ofU.A.,

501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974)................................................................................ 13

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971)...................................21

Sheehan v. Purolator Courier Corp., 676 F.2d 877 (2d Cir. 1981) ......................16

United States v. Brennan, 650 F.3d 65 (2d Cir. 2011)............................................. 1

United States v. City o f New York, — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 07 Civ.

2067, 2012 WL 745560 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 8, 2012)......................................... 3, 20

United States v. New York, 475 F. Supp. 1103 (N.D.N.Y. 1979).......................... 22

Vulcan Society o f New York City Fire Department, Inc. v. Civil

Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973)...................................... 1, 5, 6

Vulcan Society o f New York City Fire Department, Inc. v. Civil

Service Commission, 360 F. Supp. 1265 (S.D.N.Y. 1973)...................... 5, 11, 29

Wagner v. Taylor, 836 F.2d 566 (D.C. Cir. 1987).................................................. 16

Statutes

29 U.S.C. § 160(c)...................................................................................................16

42U.S.C. § 1981a....................................................................................................18

42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq..............................................................................................2

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)........................................................................................... 14

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)(l)...................................................................................... 19

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241 (1964).................. 6, 14

Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991)................. 18

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, 86

Stat. 103 (1972).............................................................................................. 7, 14

Legislative Materials

112 Cong. Rec. 6091 (1966)..................................................................................... 6

v

118 Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972)............................................................................. 8, 10

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972)............................................................................ 15, 17

Equal Employment Opportunities Enforcement Act: Hearings on S.

2453 Before the Subcommittee on Labor o f the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare, 91st Cong. (1969)............................................. 6, 7

H.R. Rep. No. 88-914 (1963), reprinted in 1964 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2391 ................... 14

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238 (1971), reprinted in 1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2137........7, 10, 15

H.R. Rep. No. 102-40(1) (1991), reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 529.......... 12, 18

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (1971), reprinted in Senate Committee on Labor

and Public Welfare, 92d Cong., Legislative History o f the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972 (1972).......................................................7

Other Authorities

David A. Goldberg, Courage Under Fire: African American

Firefighters and the Struggle for Racial Equality (Feb. 2006)

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts

Amherst)....................................................................................................... 10, 11

Denise M. Hulett et al., Enhancing Women’s Inclusion in Firefighting

in the USA, 8 Inf 1 J. of Diversity in Organisations, Communities &

Nations 189 (2008)................................................................................................ 9

Minna J. Kotkin, Public Remedies for Private Wrongs: Rethinking the

Title VII Back Pay Remedy, 41 Hastings L.J. 1301 (1990).................................15

Note, Legal Implications o f the Use o f Standardized Ability Tests in

Employment and Education, 68 Colum. L. Rev. 691 (1968).............................. 21

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, For ALL the people . . . By ALL the

people: A Report on Equal Opportunity in State and Local

Government Employment (1969)................................................................ 8, 9, 10

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 7 04/13/2012 580261 39

vi

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 8 04/13/2012 580261 39

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE1

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is a non-profit

legal organization established under New York law more than seven decades ago

to assist African Americans and other people of color in securing their civil and

constitutional rights. Since the enactment of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, LDF has worked to enforce this landmark statute, challenging discriminatory

practices of both private and public employers, including in the original Vulcan

Society litigation. See Vulcan Soc’y o f N.Y.C. Fire Dep’t, Inc. v. Civil Serv.

Comm’n, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973); see also Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 130

S. Ct. 2191 (2010); Cooper v. Fed. Reserve Bank o f Richmond, 467 U.S. 867

(1984); Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467 U.S. 561 (1984); Franks

v. Bowman Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); United States v.

Brennan, 650 F.3d 65 (2d Cir. 2011).

1 This brief is filed with the consent of all parties. Pursuant to Federal Rule of

Appellate Procedure 29(c)(5), counsel for the amicus states that no counsel for a

party authored this brief in whole or in part, and that no person other than the

amicus, its members, or its counsel made a monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief.

1

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 9 04/13/2012 580261 39

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Employment discrimination has proved more difficult to eliminate in

firefighting than in perhaps any other employment sector. Six years after the

passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq.,

Congress extended Title VII to cover municipal employers because it was

particularly concerned by the pervasive exclusion of African Americans and other

minorities from fire departments nationwide. While some fire departments across

the nation have made limited progress “to reflect the communities they serve,

employment as a New York City firefighter—arguably ‘the best job in the

world’—has remained a stubborn bastion of white male privilege,” as this case

vividly illustrates. SA85.2

The federal courts have played a critical role in the long struggle to eradicate

discrimination in firefighting because they have been able to make full use of the

broad equitable powers that Congress authorized, when it enacted Title VII in

1964, and later augmented, when it amended the statute in 1972. It is well

established that these equitable powers are equally robust and necessary to fulfill

Congress’s goal of eliminating barriers to equal employment opportunity, whether

a court is crafting a remedy for intentional discrimination or for practices that are

2 “SA__” and “JA__” refer, respectively, to the Special Appendix and Joint

Appendix filed with the City’s opening brief.

2

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 10 04/13/2012 580261 39

“discriminatory in operation.” Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 431

(1971).

Misconstruing decades of precedent and clear congressional intent, the City

seeks to curtail the authority of courts to effectively remedy Title VII violations. It

bears emphasis that, in this appeal, the City does not contest, City Br. 3 n.2, 5, 9,

the district court’s liability finding that two entry-level firefighter examinations, as

they were utilized from 1999 to 2007, had a severe and unjustified disparate impact

on African-American and Latino applicants. JA428-520. Yet, according to the

City, the only lawful remedies for this uncontested disparate-impact discrimination

were those portions of the December 2011 remedial injunction barring future use

of the challenged examinations and requiring the development and administration

of a new test that complies with Title VII. SA156-58; City Br. 5, 94.3

Notwithstanding the City’s argument to the contrary, the district court’s

additional injunctive relief does not constitute an abuse of discretion. City Br. 67.

Specifically, the City challenges the provisions in the December 2011 remedial

injunction that require it to: (a) evaluate its recruitment strategies and identify best

Moreover, this appeal does not address the district court’s more recent

remedial order awarding aggregate gross backpay damages of $128,696,803

(subject to mitigation) and priority hiring of 293 candidates from among the

African Americans and Latinos who sat for the challenged examinations and were

not hired. See United States v. City o f New York, — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 07 Civ.

2067, 2012 WL 745560 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 8, 2012).

3

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 11 04/13/2012 580261 39

practices for outreach to African-American and Latino candidates; (b) combat high

attrition rates, especially for African-American and Latino applicants who pass the

written examination but are deterred by the lengthy period that elapses before they

proceed to subsequent stages in the hiring process; (c) revise post-exam screening

procedures, especially the City’s standardless use of arrest records to exclude

applicants who were arrested but never convicted, a practice which negatively

affects African-American and Latino applicants because they are more likely to

have been arrested in the City than whites; and (d) retain an independent consultant

to recommend changes within the FDNY’s chronically under-resourced Equal

Employment Opportunity office, and the City as a whole, in order to eliminate

barriers to compliance with equal employment opportunity law. According to the

City, these portions of the remedial injunction, which it characterizes as

“affirmative relief,” exceed the scope of the uncontested disparate-impact liability

finding and cannot be supported by the district court’s intentional discrimination

finding because that ruling is flawed and must be reversed. City Br. 84-95.

For the reasons stated by Plaintiffs-Intervenors, Vulcan Soc’y Br. 98-134,

this Court should uphold the district court’s finding that the City’s long-standing

reliance on discriminatory testing procedures constituted a pattern and practice of

intentional discrimination against African-American applicants in violation of Title

VII and the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution. JA1372, JA1410-31.

4

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 12 04/13/2012 580261 39

Indeed, the FDNY’s discriminatory practices are exactly the sort of conduct

highlighted in the legislative history of the 1972 amendments to justify extending

coverage of Title VII to municipal employers. The long history of federal judicial

intervention to address discrimination in the FDNY began the following year,

when Judge Weinfeld held that the City’s firefighter hiring examinations

unlawfully discriminated against African-American and Latino applicants. Vulcan

Soc’y o f N.Y.C. Fire Dep’t, Inc. v. Civil Serv. Comm’n, 360 F. Supp. 1265, 1277

(S.D.N.Y.), aff’d in relevant part, 490 F.2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973). Despite that

finding and an aggressive remedy, the City purposefully and persistently

obstmcted efforts to rectify its unfair hiring practices. JA1402, JA1421-27. As a

result, the percentage of African-American firefighters in the FDNY stood at just

3.4% when this case was filed in 2007. JA1386.

While the December 2011 remedial injunction is fully supported by the

district court’s finding of intentional discrimination, amicus LDF respectfully

suggests that it may be unnecessary to resolve the City’s challenge to that ruling.

This Court can affirm on the alternate grounds that all of the injunctive relief

ordered by the district court constitutes an appropriate remedy for the uncontested

disparate-impact violation. See Hutchison v. Deutsche Bank Sec. Inc., 647 F.3d

479, 481 (2d Cir. 2011) (affirming judgment on alternate grounds). To the extent

that there are limitations on affirmative relief, they apply only to long-term hiring

5

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 13 04/13/2012 580261 39

quotas or other preferential treatment of individual employees or applicants based

on race—a type of remedy that the district court has not ordered in this case.

Indeed, the race-neutral injunctive relief that the City challenges is far more

modest than the remedy upheld by this Court decades ago in the original Vulcan

Society litigation. See 490 F.2d at 391, 398-99.

ARGUMENT

I. Entrenched discrimination in firefighting was a key factor that

prompted Congress to extend Title VII to public employers in 1972.

Widespread racial discrimination in public employment generally—and in

fire departments in particular—prompted Congress to extend Title VII to state and

local government employers in 1972, as the congressional record and other

contemporaneous evidence makes clear. The district court’s liability findings and

remedial injunction must be viewed in light of this history.

A. In 1972, Congress found rampant exclusion of African

Americans from fire departments nationwide.

As originally enacted, Title VII exempted state and local employers. See

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, § 701(b), 78 Stat. 241, 253 (1964).

Immediately following the statute’s enactment, this exemption was identified as a

serious shortcoming. See, e.g., 112 Cong. Rec. 6091-94 (1966) (statement of Sen.

Javits); Equal Employment Opportunities Enforcement Act: Hearings on S. 2453

Before the Subcomm. on Labor o f the S. Comm, on Labor and Pub. Welfare, 91st

6

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 14 04/13/2012 580261 39

Cong. 73 (1969) (statement of Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel, NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.); id. at 167-68 (statement of Howard Glickstein,

Staff Director, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights).

In 1972, Congress amended Title VII and redefined “employer” to include

state and local governments, governmental agencies, and political subdivisions.

See Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (the “1972 Act”), Pub. L. No.

92-261, § 2, 86 Stat. 103, 103 (1972). In adopting this amendment, Congress

found that “widespread discrimination against minorities exists in State and local

government employment, and . . . the existence of this discrimination is

perpetuated by . . . both institutional and overt discriminatory practices.” H.R.

Rep. No. 92-238 (1971), reprinted in 1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2137, 2152. Congress

further determined that “employment discrimination in State and local

governments is more pervasive than in the private sector.” Id.; see also S. Rep.

No. 92-415, at 10 (1971), reprinted in S. Comm, on Labor and Pub. Welfare, 92d

Cong., Legislative History o f the Equal Employment Opportunity Act o f 1972, at

419 (1972).

Congress singled out fire departments as among the most egregious

employers that justified extension of Title VII: “Barriers to equal employment are

greater in police and fire departments than in any other area of State and local

government. . . . Negroes are not employed in significant numbers in police and

7

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 15 04/13/2012 580261 39

fire departments.” 118 Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972) (quoting U.S. Comm’n on Civil

Rights, For ALL the people . . . By ALL the people: A Report on Equal

Opportunity in State and Local Government Employment 119 (1969) [hereinafter

1969 USCCR Report]).4

Well into the 1960s, those few African Americans who were hired were

frequently assigned to segregated firehouses. See, e.g., 1969 USCCR Report 71;

McNamara v. City o f Chicago, 959 F. Supp. 870, 874 (N.D. 111. 1997) (Chicago

maintained segregated firefighting companies until 1965), aff’d, 138 F.3d 1219

(7th Cir. 1998); Harper v. Mayor & City Council o f Baltimore, 359 F. Supp. 1187,

1195 n.ll (D. Md.) (“Segregation persisted in the Baltimore Fire Department for

more than a decade after [Brown v. Bd. ofEduc., 347 U.S. 483 (1954)].”), aff’d in

relevant part sub nom. Harper v. Kloster, 486 F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973).

These segregative and racially exclusive practices were reinforced by the

unique work environment in fire departments. See 1969 USCCR Report 87

(“[T]he unusual working arrangement of firemen has given rise to many forms of

prejudiced attitudes and treatment.”). Firefighters are typically assigned to work

twenty-four-hour shifts and must live and eat at their fire station while on duty.

4 As the Supreme Court has noted, in extending Title VII to state and local

employers, Congress relied heavily upon the 1969 USCCR Report, which detailed

pervasive racial discrimination in public employment and particularly in

firefighting. Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 449-50 n.10 (1982) (noting

Congress’s reliance on the 1969 USCCR Report).

8

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 16 04/13/2012 580261 39

See Mems v. City o f St. Paul, Dep 7 of Fire & Safety Servs., 327 F.3d 771, 775 (8th

Cir. 2003); Denise M. Hulett et al., Enhancing Women’s Inclusion in Firefighting

in the USA, 8 Int’l J. of Diversity in Organisations, Communities & Nations 189,

190 (2008). While these facets of firefighting—combined with its prestige, good

pay, job security, and valuable societal contribution—have made it a desirable job

for many Americans, they have also created an organizational culture particularly

resistant to racial integration. Thus, even after fire departments officially

desegregated, African-American firefighters were routinely barred from using the

same living and sleeping quarters as whites. For example, after Washington, D.C.

firehouses were desegregated in the 1960s, black firefighters were required for

more than a decade to sleep in designated “C” beds and eat from separate “C”

dishes and “C” utensils, for “Colored.” Hammon v. Barry, 813 F.2d 412, 434

(D.C. Cir. 1987); see also 1969 USCCR Report 71, 89 (finding that the only black

firefighter employed in San Francisco in 1967 was required to carry his own

mattress between stations during his training period).

Of particular relevance here, Congress concluded that segregation and hiring

barriers were often paired with widespread refusal to recruit African-American

candidates: “[Fjire departments have discouraged minority persons from joining

their ranks by failure to recruit effectively and by permitting unequal treatment on

the job including unequal promotional opportunities, discriminatory job

9

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 17 04/13/2012 580261 39

assignments, and harassment by fellow workers.” 118 Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972)

(quoting 1969 USCCR Report 120). Congress also cited specific barriers to fair

employment in fire departments, including the use of “selection devices which are

arbitrary, unrelated to job performance, and result in unequal treatment of

minorities.” Id. (quoting 1969 USCCR Report 119).

Finally, Congress was especially concerned that continued discrimination in

firefighting and other highly visible jobs impaired government performance and

democratic accountability: “The problem of employment discrimination is

particularly acute and has the most deleterious effect in these governmental

activities which are most visible to the minority communities . . . with the result

that the credibility of the government’s claim to represent all the people equally is

negated.” H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 2153.

B. Racial exclusion in the FDNY was severe prior to the 1972 Act

and has persisted.

New York was no exception to this widespread pattern of racial

discrimination in firefighting. In 1963, just 4.15% of all FDNY employees, in any

title, were African American. JA1386. In the period leading up to the 1972 Act,

not only did the FDNY manipulate hiring procedures to screen out African-

American applicants, but it frequently excluded those who were hired from

coveted positions, such as drivers and fire inspectors, and instead “[rjelegated

[them] to . . . the toughest, most dangerous, and least public assignments.” David

10

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 18 04/13/2012 580261 39

A. Goldberg, Courage Under Fire: African American Firefighters and the Struggle

for Racial Equality 73, 125-29 (Feb. 2006) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Massachusetts Amherst). In addition, African-American firefighters

regularly experienced harassment and physical threats from both white

counterparts and senior management. Id. at 73.

Not much changed after the 1972 Act went into effect. In 1973, when the

Vulcan Society won its original litigation against the City, African Americans and

Latinos accounted for just 5% of the firefighting force, although they made up 32%

of the city’s population. Vulcan Soc’y, 360 F. Supp. at 1269. “The subsequent

history of the FDNY demonstrates that whatever practical effect Judge Weinfeld’s

injunction may have had on minority hiring dissipated shortly after the injunction

expired” in 1977. JA1386. Strikingly, the percentage of African-American

firefighters in the FDNY was approximately the same when this case was filed in

2007 as it was in 1973. Id. (“Between 1991 and 2007, black firefighters never

constituted more than 3.9% of the force, and by the time this case was filed in

2007, the percentage of black firefighters in the FDNY had dropped to 3.4%.”).

The FDNY, unfortunately, has purposely and persistently thwarted efforts to

address its history of racial exclusion. Vulcan Soc’y Br. 8-36. To be sure,

discriminatory practices persist elsewhere, and indeed, Congress relied specifically

on widespread evidence of discrimination in firefighting to support its amendments

11

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 19 04/13/2012 580261 39

to Title VII in 1991. See H.R. Rep. No. 102-40(1), at 99-100 (1991), reprinted in

1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 549, 637-38. Nevertheless, the FDNY lags far behind other

major American cities in terms of its dismally low rates of African-American and

Latino firefighters. Vulcan Soc’y Br. 8-36; U.S. Br. 7-9 (charts demonstrating that

New York has the lowest ratio of African-American and Latino firefighters among

eight of the largest cities in the nation). Thus, the City’s attempt to limit the scope

of relief available here would frustrate Congress’s intent to desegregate municipal

employment generally and fire departments in particular. Indeed, absent an

efficacious remedy, the FDNY, which is the largest fire department in the nation,

seems impervious to meaningful changes that could redress its severe and

pervasive discrimination.

II. Title VII vests courts with wide latitude to exercise their equitable

powers to address disparate-impact discrimination.

To the extent that limited progress has been made in fire departments across

the nation, it has required diligent and persistent judicial intervention. See, e.g.,

Lewis v. City o f Chicago, 643 F.3d 201 (7th Cir. 2011) (affirming scope of remedy

for unjustified disparate impact on African Americans caused by Chicago’s

repeated utilization of a hiring examination administered sixteen years earlier);

Bradley v. City o f Lynn, 443 F. Supp. 2d. 145, 173-76 (D. Mass. 2006) (holding

that Massachusetts violated Title VII by using state-wide firefighter hiring

examinations that had an unjustified adverse impact on minority candidates and

12

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 20 04/13/2012 580261 39

noting that “not much has changed” since a prior judicial remedy thirty years

earlier). In some municipalities where courts have successfully overseen

implementation of broad remedial measures, firefighting is now a career path that

is more accessible to communities of color. See Br. of Amicus Curiae Inf 1 Ass’n

of Black Prof 1 Firefighters, Part II (describing the success of court remedies in the

San Francisco Fire Department). The importance of court-ordered remedies in

furthering progress in other fire departments demonstrates the need for the

appropriate exercise of equitable remedial authority to remedy the continuing

effects of the uncontestedly discriminatory examinations that the City utilized from

1999 to 2007. JA428-520.

Where, as here, ‘“a violation of Title VII is established, the district court

possesses broad power as a court of equity to remedy the vestiges of past

discriminatory practices.’” Ass’n Against Discrimination in Emp’t, Inc. v. City o f

Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256, 278 (2d Cir. 1981) (quoting Rios v. Enter. Ass’n

Steamfitters Local 638 ofU.A., 501 F.2d 622, 629 (2d Cir. 1974)); see also Newark

Branch, NAACP v. Town o f Harrison, 940 F.2d 792, 806 (3d Cir. 1991); Berkman

v. City o f New York, 705 F.2d 584, 594 (2d Cir. 1983); U.S. Br. 28-29. As the

district court correctly recognized, see SA102-03, the “full range of equitable

remedies [is] available in disparate impact cases as well” as disparate treatment

cases. In re Emp’t Discrimination Litig. Against Ala., 198 F.3d 1305, 1315 n.13

13

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 21 04/13/2012 580261 39

(11th Cir. 1999). Notwithstanding the City’s contentions to the contrary, City

Br. 84, this broad equitable authority to remedy both disparate-impact and

disparate-treatment discrimination is well established by the Title VII’s text,

legislative history, and settled precedent.

A. The plain language and legislative history of Title VII establish

Congress’s intent to provide courts with broad authority to

remedy employment discrimination in all forms.

1. With the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress unequivocally sought to root

out employment discrimination in all forms. See H.R. Rep. No. 88-914 (1963),

reprinted in 1964 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2391, 2401. To accomplish this goal, Congress

included a broad remedial provision, section 706(g), which empowers courts not

only to enjoin discriminatory conduct but also to “order such affirmative action as

may be appropriate.” Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, § 706(g), 78

Stat. 241, 261 (codified, as amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)) [hereinafter

section 706(g)],

When Congress amended Title VII in 1972, it made a revision that was just

as critical as removing the exemption for fire departments and other municipal

employers. See Part I.A supra. It expanded section 706(g) to authorize the courts

to order “any other equitable relief as [they] deem[] appropriate,” in addition to

backpay, injunctive relief, “affirmative action,” and other remedies originally

authorized. 1972 Act, Pub. L. No. 92-261, § 4, 86 Stat. 103, 104-07 (1972). As

14

Case: 11-5.113 Document: 152 Page: 22 04/13/2012 580261 39

the legislative history illustrates, this amendment responded to concerns that “the

machinery created by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [was] not adequate” to ensure

equal employment opportunity. H.R. Rep. No. 92-238 (1971), reprinted in 1972

U.S.C.C.A.N. 2137, 2139. Congress therefore reaffirmed that Title VII’s remedial

provision was “intended to give the courts wide discretion exercising their

equitable powers to fashion the most complete relief possible.” 118 Cong. Rec.

7168 (1972); see also Minna J. Kotkin, Public Remedies for Private Wrongs:

Rethinking the Title VII Back Pay Remedy, 41 Hastings L.J. 1301, 1326 (1990)

(noting that the additional remedial language inserted in section 706(g) in 1972

was “directed to increasing and confirming flexibility, rather than to restricting

options for relief’).

2. The Supreme Court has repeatedly relied on this legislative history as

“emphatic confirmation that federal courts are empowered to fashion such relief as

the particular circumstances of a case may require.” Franks v. Bowman Transp.

Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763-64 (1976); see also Local 28 o f Sheet Metal Workers’ Int’l

Ass’n v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421, 445-46 (1986) (acknowledging broad remedial

powers vested to federal courts under Title VII); Int’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324, 364 (1977) (same); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405, 420-21 (1975) (same). Similarly relying on pertinent legislative history, this

Court concluded:

15

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 23 04/13/2012 580261 39

[W]e are persuaded that Congress intended the federal courts to have

resort to all of their traditional equity powers, direct and incidental, in

aid of the enforcement of [Title VII]. Having stated its aim to

eradicate employment discrimination, Congress made explicit

statutory attempts to forestall possible efforts to frustrate the

achievement of its goal.

Sheehan v. Purolator Courier Corp., 676 F.2d 877, 885 (2d Cir. 1981); see also

Wagner v. Taylor, 836 F.2d 566, 572 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (observing that the

legislative history makes clear that Congress vested courts with “broad statutory

powers designed to effectuate and preserve the rights of Title VII claimants”);

Garcia v. Lawn, 805 F.2d 1400, 1403 (9th Cir. 1986).

The Supreme Court has also placed considerable weight on the fact that

Congress modeled section 706(g), including its authorization of “affirmative

action,” after the remedial section of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), 29

U.S.C. § 160(c). See Franks, 424 U.S. at 769-70; Local 28, 478 U.S. at 446 n.26.

That provision provides the National Labor Relations Board with broad discretion

not only to enjoin unlawful labor practices, but also to require employers to take

affirmative measures that accomplish the NLRA’s objectives. See Republic Steel

Corp. v. NLRB, 311 U.S. 7, 12 (1940). Tellingly, in Franks, the Supreme Court

observed that, in light of the 1972 Act, section 706(g) now vests courts with even

greater remedial powers than the NLRA. Franks, 424 U.S. at 769 n.29.

3. The expansive remedial authorization in section 706(g) as originally

enacted is not limited to cases of intentional discrimination; nor does the even

16

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 24 04/13/2012 580261 39

broader remedial authorization added in 1972 distinguish between relief for

disparate-treatment and disparate-impact discrimination, even though this

amendment was enacted against the backdrop of the Supreme Court’s seminal

decision two years earlier in Griggs, 401 U.S. at 430 (holding that Title VII

prohibits “practices, procedures, or tests neutral on their face, and even neutral in

terms of intent” that “operate to ‘freeze’ the status quo of prior discriminatory

employment practices”).

Four years after Griggs and two years after the 1972 Act, the Supreme Court

confirmed that Title VII’s broad remedial powers apply equally to disparate-impact

and disparate-treatment cases. In Albemarle Paper Co., the district court found

that the company’s employment tests and other policies had an unjustified adverse

impact on the basis of race, but it declined to award backpay because there was no

evidence of “bad faith.” 422 U.S. at 413. Relying on the legislative history of the

1972 amendments, the Supreme Court rejected this reasoning as inconsistent with

Congress’s mandate. Id. at 420-21 (citing 118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972)). The

Court emphasized what the legislative record makes clear: District courts have

‘“not merely the power but the duty to render a decree which will so far as possible

eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in

the future.’” Id. at 418 (quoting Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 154

(1965)). Thus, Title VII’s remedial provision authorizes—and indeed, requires—

17

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 25 04/13/2012 580261 39

that district courts do much more than simply enjoin a test that has an unjustified

and racially disparate impact.

Congress’s firm commitment to broad judicial authority to redress disparate-

impact discrimination is also evident in the Civil Rights Act of 1991, Pub. L. No.

102-166, 105 Stat. 1071 (1991) (the “1991 Act”). Troubled by a string of Supreme

Court decisions that limited the reach of Title VII, Congress sought to restore the

strength of the statute to promote equal opportunity. H.R. Rep. No. 102-40(1)

(1991), reprinted in 1991 U.S.C.C.A.N. 549, at 552. Congress underscored the

disparate-impact holdings of Albemarle and Griggs—-which the House Report

called “the single most important Title VII decision”—by expressly enshrining

them into the Act. See id. at 562.5

In sum, the plain text and legislative history of Title VII, as confirmed by

settled precedent, firmly establish that Congress intended courts to have “‘not

merely the power but the duty” to use Title VII’s remedial powers as fully as

possible to eradicate both disparate-impact and disparate-treatment discrimination.

5 In addition to reaffirming Griggs, the 1991 Act expanded remedies for

intentional discrimination to include punitive damages in certain circumstances.

See Pub. L. No. 102-166, § 102, 105 Stat. 1071, 1072 (codified at 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981a). While the Act did not authorize such relief for disparate-impact

discrimination, the legislative history makes clear that Congress “determined that

victims of employment discrimination were entitled to additional remedies . . .

without giving any indication that it wished to curtail previously available

remedies.” Pollard v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 532 U.S. 843, 852 (2001)

(emphasis in original).

18

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 26 04/13/2012 580261 39

Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 421 (citation and quotation marks omitted).

B. Section 706(g) authorizes, and courts frequently impose,

affirmative relief to remedy disparate-impact violations.

As amended, section 706(g) vests district courts with the power, inter alia,

to “enjoin the [employer] from engaging in [an] unlawful employment practice,” to

“order such affirmative action as may be appropriate,” and to award “any other

equitable relief as the court deems appropriate.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)(l). This

Court has explained that Title VII remedies fall into three categories:

compensatory relief, “designed to ‘make whole’ the victims of the defendant’s

discrimination”; compliance relief, “designed to erase the discriminatory effect of

the challenged practice and to assure compliance with Title VII in the future”; and

affirmative relief, “designed principally to remedy the effects of discrimination that

may not be cured by the granting of compliance or compensatory relief.”

Berkman, 705 F.2d at 595-96; Ass’n Against Discrimination in Emp’t, Inc., 647

F.2d at 280.

The City contends that it was an abuse of discretion for the district court to

award any “affirmative relief’; the only lawful aspects of the December 2011

remedial injunction, in the City’s view, were those barring future use of the

discriminatory examinations and requiring development and administration of a

19

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 27 04/13/2012 580261 39

new Title VH-compliant examination. City Br. 86-94.6 To the extent that the City

accurately characterizes the remaining portions of the remedial injunction as

affirmative relief, its assertion that Title VII “presumptively limits affirmative

relief—[as opposed to] compliance or compensatory relief—to cases of intentional

discrimination,” City Br. 85, misconstrues well-established precedent.

First, the City’s reliance on the text of section 706(g) is misplaced. City Br.

85. “The requirement that an employer have discriminated ‘intentionally’ in order

for the provisions of § 706(g) to come into play means not that there must have

been a discriminatory purpose, but only that the acts must have been deliberate, not

accidental.” Ass ’n Against Discrimination in Emp 7, 647 F.2d at 280 n.22; accord

In re Emp’t Discrimination Litig. Against Ala., 198 F.3d at 1315 n.13 (section

706(g) ‘“requires only that the defendant meant to do what he did, that is, his

6 These uncontested portions of the remedial injunction are indisputably

compliance relief. See Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596. Moreover, although not the

subject of this appeal, the backpay damages and priority hiring required by the

district court’s March 2012 order, see City o f New York, 2012 WL 745560, are

compensatory, and perhaps compliance, relief as well. See Berkman, 705 F.2d at

596 (compensatory relief includes backpay); id. at 595-96 (“To the extent that an

order requires the hiring of a member of the plaintiff class—i. e., a victim of the

discrimination—it constitutes both compliance relief and compensatory relief.”).

y

Some of the remedies that the City challenges more properly could be

characterized as compliance relief. As this Court has observed, compliance relief

includes forward-looking remedies to bring the employer into compliance with

Title VII. See Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596. That is precisely what the district court

did when it ordered the City, inter alia, to maintain records of communications

concerning firefighter candidates and reform its Equal Employment Opportunity

office. SA163-64, SA168-71.

20

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 28 04/13/2012 580261 39

employment practice was not accidental’”) (quoting Local 189, United

Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980, 996 (5th Cir.

1969)); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 796 (4th Cir. 1971) (rejecting

position that section 706(g) “requires that plaintiffs prove the existence of a

discriminatory intent”); see also Note, Legal Implications o f the Use o f

Standardized Ability Tests in Employment and Education, 68 Colum. L. Rev. 691,

713 (1968) (willfulness requirement in section 706(g) was inserted to avoid

liability for “[accidental” or “inadvertent” acts); U.S. Br. 29-31.

Second, remedial injunctions upheld by this and other courts belie the City’s

assertion that affirmative relief for disparate-impact discrimination is “rare” or

“presumptively” unlawful. City Br. 85-86. For instance, in Berkman, this Court

expressly defined “affirmative relief’ to include “the imposition of a requirement

that the defendant actively recruit or train members of the Title VH-protected

group.” 705 F.2d at 596. Far from “rare,” City Br. 86, targeted recruitment

provisions, such as those in this case, are a common form of relief awarded to

remedy Title VII disparate-impact violations. See, e.g., NAACP v. Town of

E. Haven, 259 F.3d 113, 116-17 (2d Cir. 2001) (awarding attorneys’ fees for

decree requiring defendants “to increase awareness of job opportunities through

advertising directed to the black community and communications with black

community organizations”); Newark Branch, 940 F.2d at 806-08 (upholding decree

21

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 29 04/13/2012 580261 39

requiring defendants to engage in “affirmative activities” including “recruitment

activities directed towards potential black applicants”); Harrison v. Lewis, 559

F. Supp. 943, 950-51 (D.D.C. 1983) (ordering affirmative relief, including

“aggressive recruitment of qualified minorities” to remedy disparate-impact

violation); United States v. New York, 475 F. Supp. 1103, 1110 (N.D.N.Y. 1979)

(ordering affirmative relief, including recruitment “to attract members of the

minority community,” to remedy disparate-impact violation); Dozier v. Chupka,

395 F. Supp. 836, 859-60 (S.D. Ohio 1975) (ordering affirmative relief including

recruitment, to remedy disparate-impact violation in municipal fire department);

U.S. Br. 32-34. Indeed, aggressive recruitment is often essential to attract qualified

minority candidates to an employer—and a line of work—with a long and well-

known history of discrimination. See, e.g., Dozier, 395 F. Supp. at 849, see also

supra Part I. Here, absent affirmative efforts to attract minority candidates,

African Americans and others may be deterred from applying, given the continuing

effects of the uncontested disparate-impact finding.

C. Any limitations on affirmative relief apply only to long-term

quotas for hiring or other individualized job benefits awarded

based on race.

Affirmative relief is in no way limited, as the City contends, to those cases

where disparate-impact liability is “coupled with ‘persistent or egregious’

discriminatory conduct.” City Br. 86-87 (citing Local 28, 478 U.S. at 475-76;

22

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 30 04/13/2012 580261 39

Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596; Guardians Ass’n ofN.Y.C. Police Dep’t, Inc. v. Civil

Serv. Comm’n, 630 F.2d 79, 112-13 (2d Cir. 1980)). The City misreads the

authority upon which it relies, all of which concern a particular subset of

affirmative relief that is not at issue here: long-term quotas and other “preferential

relief’ that results in the award of jobs and other employment benefits to

individuals on the basis of race. Local 28, 478 U.S. at 444-45.

In Local 28, the Supreme Court concluded that Ҥ 706(g) does not prohibit a

court from ordering, in appropriate circumstances, [such] affirmative race

conscious relief as a remedy for past discrimination.” Id. at 445 (plurality

opinion); see also id. at 483 (Powell, J., concurring in part and concurring in the

judgment); id. at 499 (White, J., dissenting). The Court further “h[e]ld that such

relief may be appropriate where an employer or a labor union has engaged in

persistent or egregious discrimination, or where necessary to dissipate the lingering

effects of pervasive discrimination.” Id. at 445 (plurality opinion); see also id. at

483 (Powell, J., concurring in part and concurring in the judgment). Yet, a

plurality of the Justices were unwilling to rule out the appropriateness of such

relief in other contexts. Id. at 476.

Through the lens of Local 28, it is clear that this Court’s prior holdings in

Berkman and Guardians amount to no more than an endorsement of the rule

subsequently adopted by the Supreme Court. In Berkman, this Court did not hold

23

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 31 04/13/2012 580261 39

that any affirmative relief in a disparate-impact case requires an additional finding

of a “long-continued pattern of egregious discrimination.” 705 F.2d at 596.

Rather, the Court held that this “persistent or egregious” standard applies to the

subset of affirmative relief that was at issue in Local 28—namely, long-term

quotas and other preferential relief to individuals based on their race. Id. In a

subsequent ruling in Berkman, this Court clarified that it is the type of

“[ajffirmative relief that accords enhanced hiring opportunities to compensate for

the effects of past discrimination [that] is available only under limited

circumstances.” Berbnan v. City o f New York, 812 F.2d 52, 61 (2d Cir. 1987)

(emphasis added) (citing Local 28, 478 U.S. 421 (plurality opinion)). It follows

that such limitations, including Local 28's “persistent or egregious” standard, do

not apply to other forms of affirmative relief—such as the facially race-neutral

recruitment and other provisions in the December 2011 remedial injunction, none

of which allocate individual employment benefits or burdens based on race.

This Court’s decision in Guardians is not to the contrary. See 630 F.2d at

109. In Berbnan, this Court relied on Guardians, as well as Kirkland v. New York

State Department o f Correctional Services, 520 F.2d 420 (2d Cir. 1975), simply to

support its conclusion that “the relatively permanent use of a specified hiring ratio”

to eradicate the vestiges of unlawful discrimination is limited to cases involving

24

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 32 04/13/2012 580261 39

persistent or egregious discrimination. Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596-97; Guardians,

630 F.2d at 109; Kirkland, 520 F.2d at 429-30.8

III. The limited award of affirmative relief was not an abuse of discretion.

A. The “persistent or egregious” standard does not apply.

The relief challenged by the City does not include a long-term quota or

preferential hiring on the basis of race that would trigger Local 28's “persistent or

egregious standard.” In fact, the district court expressly rejected “hiring quotas in

any shape or form,” SA103, even though they were arguably justifiable in the

distinctive context of this case. See Local 28, 478 U.S. at 444-45, 481; Guardians,

630 F.2d at 108-09. Rather, the district court crafted a facially race-neutral

remedial injunction focused on improving the policies by which firefighters are

recruited as well as the post-exam screening processes. SA156-73. Section 706(g)

authorized the district court to take this approach in light of its detailed factual

findings, SA2-82, demonstrating that merely altering the written examinations

would not fully remedy the continuing effects of the City’s uncontested disparate-

impact violations, regardless of whether that discrimination also can be deemed

persistent or egregious. See Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596.

8 Yet, as this Court further held in Berkman, even hiring targets are

permissible in certain circumstances, even absent a finding of persistent or

egregious discrimination, if they are temporarily limited and tailored to

compensate for a finding of disparate-impact discrimination. See 705 F.2d at 596.

25

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 33 04/13/2012 580261 39

The district court’s emphasis on improving the City’s hiring processes in a

facially race-neutral manner is evident from the recruitment relief included in the

December 2011 remedial injunction. SA159-61. Specifically, the court ordered

the City to retain a consultant to evaluate current recruitment strategies and to

identify best practices for outreach to African Americans and Latinos. Such

targeted recruitment is “[ijnclusive as opposed to exclusive” because it “serve[s] to

broaden a pool of qualified applicants and to encourage equal opportunity.”

Honadle v. Univ. ofVt. & State Agricultural Coll., 56 F. Supp. 2d 419, 428 (D. Vt.

1999). Yet such targeted recruitment stops far short of “imposing] burdens or

benefits” based on race. Id. (collecting cases); cf. Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch.

v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701, 789 (2007) (Kennedy, J., concurring in

part and concurring in the judgment) (defining “recruiting students and faculty in a

targeted fashion” among a list of “mechanisms [that] are race conscious but do not

lead to different treatment based on a classification that tells each [individual] he or

she is to be defined by race, so it is unlikely any of them would demand strict

scrutiny to be found permissible”).

For similar reasons, the district court’s remedy to combat voluntary attrition

in the post-exam screening process was facially race-neutral and thus did not

trigger the “persistent or egregious” standard. As the district court found, the

City’s “position that firefighters should be selected on the basis of merit” is

26

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 34 04/13/2012 580261 39

undermined when so many well-qualified candidates drop out during the lengthy

(sometimes lasting four to five years) post-exam screening process. SA5-18.

Furthermore, this attrition disproportionately affects African Americans and

Latinos who are significantly less likely than whites to have informal support

mechanisms within the FDNY “encouraging them to persevere,” because minority

hiring was systemically limited by the uncontestedly discriminatory testing

procedures utilized by the City for over a decade. SA9-16. While the district court

directed the City to focus on reducing attrition in communities of color, SA161, the

remedial injunction does not mandate that any particular African Americans or

Latinos will receive a job or any other employment benefit based on their race;

indeed, if implemented effectively, this affirmative relief will reduce attrition for

candidates of all races. Cf Ricci v. DeStefano, 129 S. Ct. 2658, 2677 (2009)

(declining to apply a heightened standard of review for “an employer’s affirmative

efforts to ensure that all groups have a fair opportunity to apply for promotions and

to participate in the process by which promotions will be made”). Likewise, the

revisions ordered by the district court to address the City’s standardless use of

arrest records in the post-exam screening process was prompted by the

unjustifiable disparate impact of these practices on minority candidates, but the

required reforms should benefit all applicants, regardless of their race. SA55-57.

27

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 35 04/13/2012 580261 39

Accordingly, the district court did not abuse its discretion when it awarded a

limited array of facially race-neutral, affirmative relief designed “to make [the

City’s] equal employment opportunity compliance activities effective, [and] to

eliminate the barriers its hiring policies and practices have erected or maintained

that serve to perpetuate the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics as

firefighters in the FDNY.” SA104.

B. In any event, the FDNY’s discrimination was persistent and

egregious.

Even if, as the City contends, City Br. 86-91, the “persistent or egregious”

standard applies to the affirmative relief awarded here, both prongs are easily

satisfied by the stark and long-standing underrepresentation of African Americans

among the City’s firefighters, coupled with the uncontested disparate-impact

finding. See Berkman, 705 F.2d at 596; Ass ’n Against Discrimination in Emp’t,

Inc., 647 F.2d at 279. The district court found that, as of 2002, African Americans

made up 25% of the City’s population, but only 2.6% of the City’s firefighters.

JA429. Those statistics are worse than the numbers cited by this Court as evidence

of a flagrant racial disparity that warranted the type of long-term hiring quota that

the district court here expressly rejected. See Guardians, 630 F.2d at 113

(collecting cases and noting with approval a long-term hiring quota, where

minorities constituted 25% of population, but only 3.6% of police force). Not only

are African Americans grossly underrepresented among the City’s firefighters, but

28

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 36 04/13/2012 580261 39

the proportion of the force that is African American has remained essentially

unchanged for nearly forty years. See JA1386; Vulcan Soc’y, 360 F. Supp. at

1269; see also Part I.B supra.

Coupled with the district court’s uncontested disparate-impact finding, such

an extreme and long-standing disparity is sufficient to meet Local 28' s “persistent

or egregious” standard. See U.S. Br. 32-33 & n.9, 36-39. That conclusion is

consistent with one of the central purposes of disparate-impact liability: rooting out

employers’ prolonged reliance on discriminatory practices that operate as ‘“built-in

headwinds’ for minority groups.” Griggs, 401 U.S. at 432. Summarizing “[t]he

history of the City’s efforts to remedy its discriminatory firefighter hiring policies

. . . [as] 34 years of intransigence and deliberate indifference, bookended by

identical judicial declarations that the City’s hiring policies are illegal,” JA1421,

the district court properly concluded that affirmative relief was necessary if there is

any hope that the nation’s largest fire department will at last begin to make some

progress towards Title VII’s goal of fair hiring for all Americans.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, as well as those outlined by the United States, as

Appellee, and the Vulcan Society et al., as Appellees/Cross-Appellants, the

portions of the district court’s December 2011 remedial injunction challenged by

the City should be affirmed.

29

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 37 04/13/2012 580261 39

Dated: April 13, 2012 Respectfully submitted,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE &

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

By:_ /s/ ReNika C. Moore_______

Debo P. Adegbile, Interim Director-Counsel

Elise C. Boddie

ReNika C. Moore

Counsel o f Record

Johnathan J. Smith

Ria A. Tabacco

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(tel) 212-965-2200

(fax) 212-226-7592

Joshua Civin

1444 I Street, NW, 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

30

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 38 04/13/2012 580261 39

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

WITH TYPE-VOLUME LIMITATION, TYPEFACE REQUIREMENTS,

AND TYPE STYLE REQUIREMENTS

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(C)(i), I hereby certify that:

1. This brief complies with the type-volume limitations of Fed. R. App. P.

32(a)(7)(B), because this brief contains 6,878 words, excluding the parts of the

brief exempted by Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B)(iii).

2. This brief complies with the typeface requirements of Fed. R. App. P.

32(a)(5) and the type style requirements of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(6) because this

brief has been prepared in a proportionally spaced typeface using Microsoft Office

Word 2003 in Times New Roman 14-point font.

Dated: April 13, 2012 /s/ ReNika C. Moore

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(tel) 212-965-2234

(fax) 212-226-7592

(e-mail) rmoore@naacpldf.org

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

31

mailto:rmoore@naacpldf.org

Case: 11-5113 Document: 152 Page: 39 04/13/2012 580261 39

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that on April 13, 2012, I electronically filed the foregoing Brief of

Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. in Support of

Affirming the Judgment in Favor of Appellees with the Clerk of the Court for the

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by using the appellate

CM/ECF system. I further certify that all participants in this case are registered

CM/ECF users and that service will be accomplished by the appellate CM/ECF

system.

/s/ ReNika C. Moore

ReNika C. Moore

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(tel) 212-965-2200

(fax) 212-226-7592

(e-mail) rmoore@naacpldf.org

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

32

mailto:rmoore@naacpldf.org