Correspondence from Butler to Chambers

Correspondence

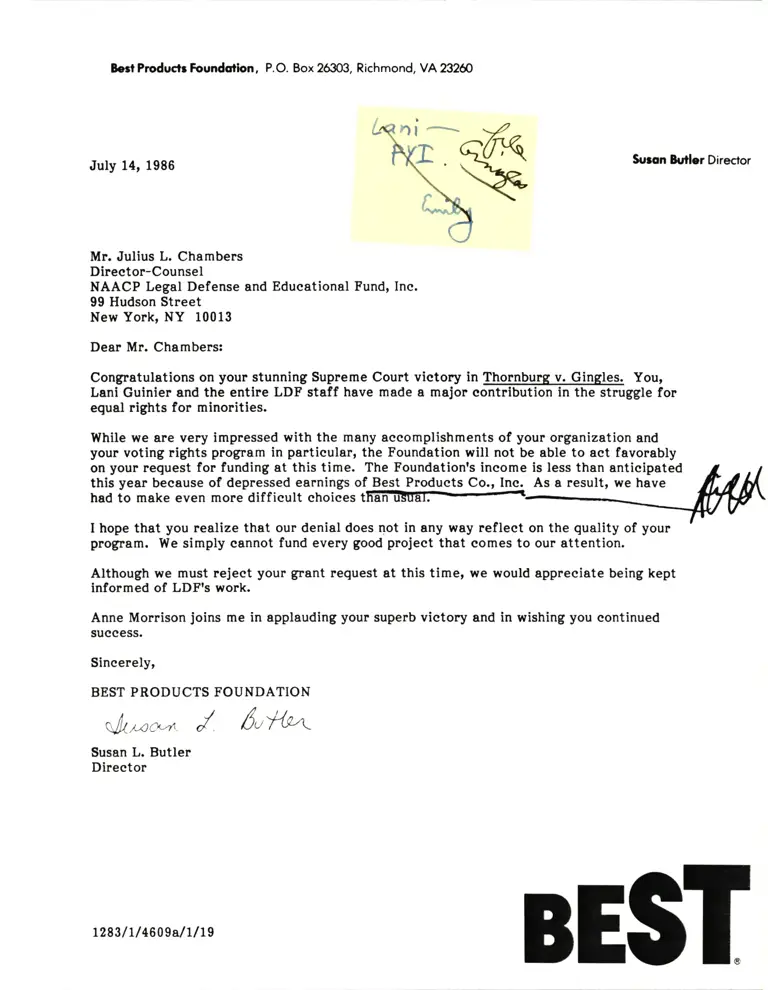

July 14, 1986

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Butler to Chambers, 1986. 96fa8c3a-dd92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aabbeba3-eacf-4d24-b26f-bfc0a7b75aae/correspondence-from-butler-to-chambers. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

3cd Produclr Foundotbn, P.O. Box 263C8, Richmond, VA2326f-

Surcn Butlcr DirectorJuly 14, 1986

Mr. Julius L. Chambers

Direetor-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Dear Mr. Chambers:

Congratuletions on your stunning Supreme Court victory in Thornburg v. Gingles. You,

Lani Guinier and the entlre LDF staff have made a major contrlbution ln the struggle for

equel rights for minorities.

While we are very impressed with the many aeeomplishments of your organization and

your voting rights program in partieular, the Foundation will not be able to aet favorably

on your request for funding at this time. The Foundationfs ineome is less than antieipated

this year beeause of depressed earnings of Best Produets Co., Inc. As a result, we have

had to make even more diffieult ehoiees

I hope that you realize that our denial does not in any way refleet on the quality of your

progtam. We simply eannot fund every good project that comes to our attention.

Although we must rejeet your grant request at this time, we would appreciate being kept

informed of LDFrs work.

Anne Morrison joins me in applauding your superb vietory and in wishing you eontinued

sueeess.

Sineerely,

BEST PRODUCTS FOUNDATION

tJ

VlaAn, d

Susan L. Butler

Director

6"r1s-^-

L283lL/4609alLltg BEST