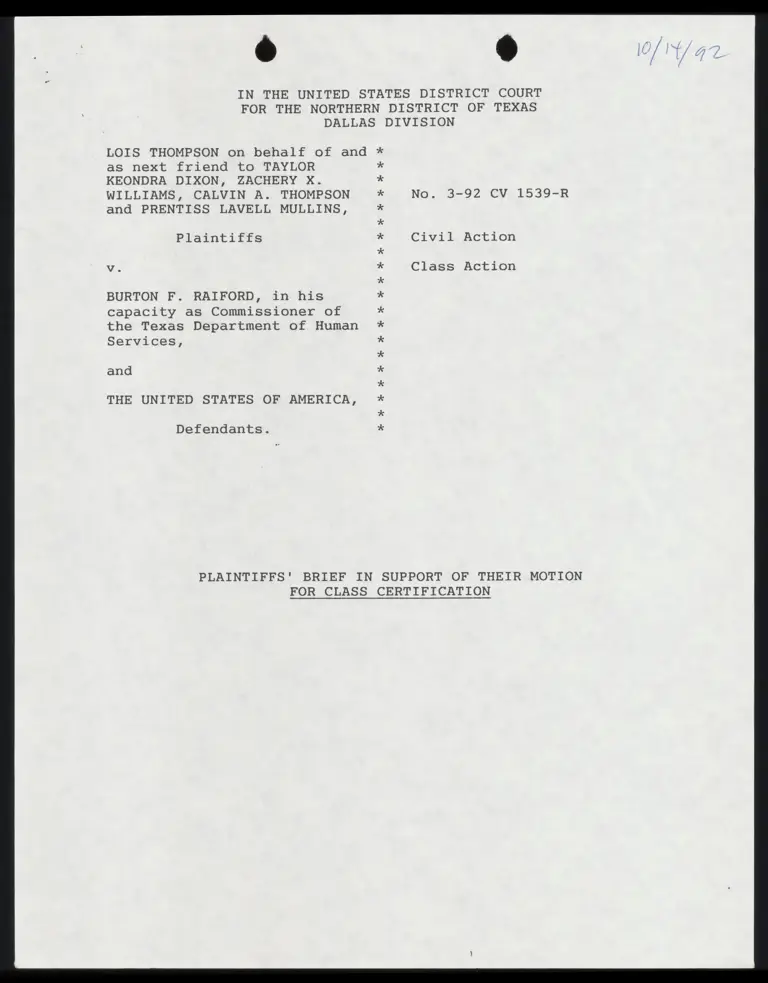

Plaintiffs' Brief in Support of Their Motion for Class Certification with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

October 14, 1992

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thompson v. Raiford Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Brief in Support of Their Motion for Class Certification with Certificate of Service, 1992. cdf00973-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/aac9047c-0f56-4afe-82b2-3a783cd78861/plaintiffs-brief-in-support-of-their-motion-for-class-certification-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

} 0/ | SL / — | | NL 5

hig | / ¢ { L.

/ / /

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

DALLAS DIVISION

LOIS THOMPSON on behalf of and

as next friend to TAYLOR

KEONDRA DIXON, ZACHERY X.

WILLIAMS, CALVIN A. THOMPSON

and PRENTISS LAVELL MULLINS,

No. 3-92 CV 1539-R

Plaintiffs Civil Action

Vv. Class Action

BURTON F. RAIFORD, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

the Texas Department of Human

Services,

and

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

o

d

H

H

X

H

XH

NH

Sk

H

¥

dH

2%

FX

F

F

FX

X

X

*

Defendants.

PLAINTIFFS' BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THEIR MOTION

FOR CLASS CERTIFICATION

“ »

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

National class

Local Rule 10.2 (1) appropriate Rule 23 sections 1

Local rule 10.2 (2) specific factual allegations

and common questions 4

1. The number or approximate number of class members 4

2. The definition of the class 4

3. A description of the distinguishing and

common characteristics of class members

in terms of geography, time, common

financial incentives, etc. 5

4. The questions of law and fact claimed to

be common to the class

Local rule 10.2 (3) adequate representation 6

1. Tvplcality’ 6

2. Fair and adequate representative of the class 6

3. Financial responsibility to fund the action 7

Local rule 10.2 (4) jurisdictional amount 7

Local rule 10.2 (5) notice to the class 7

Local rule 10.2 (6) class discovery 7

Local rule 10.2 (7) plaintiffs attorneys fees 7

Other litigation 8

Standing of plaintiffs to bring a national class action 8

Discretion of the Court 9

Statewide class 9

Local Rule 10.2 (1) appropriate Rule 23 sections 9

Local rule 10.2 (2) specific factual allegations

and common questions 13

1. The number or approximate number of class members

2. The definition of the class

3. A description of the distinguishing and

common characteristics of class members

in terms of geography, time, common

financial incentives, etc.

4. The questions of law and fact claimed

to be common to the class

Local rule 10.2 (3) adequate representation

1. Typicality

2. Fair and adequate representative of the class

3. Financial responsibility to fund the action

Local

Local

Local

Local

Other

rule 10.2 (4)

rule 10.2 (5)

rule 10.2 (6)

rule 10.2 (7)

litigation

jurisdictional amount

notice to the class

class discovery

plaintiffs attorneys fees

Standing of plaintiffs to bring a statewide class action

Discretion of the Court

ii

13

13

14

14

14

15

15

15

16

16

16

16

16

17

17

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Califano v. Yamasaki, 442 U.S. 682 (1979)

Childress v. Secretary of HHS, 679 F.2d 623

{6th Cir. 1982)

Hyatt v. Sullivan, 899 F.2d 329 (4th Cir. 1990)

Johnson v. United States Railroad Retirement Board,

969 F.24 1082 (D.C. Cir. 1992)

Kuenz v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 104 F.R.D. 474

(D. Mo. 1985)

Lopez v. Heckler, 725 F.2d 1489 (9th Cir. 1984)

vacated on other grounds and remanded,

469 U.S. 1082 (1984)

Lynch v. Rank, 604 F.Supp. 30 (N.D. Ca. 1984)

Mertz v. Harris, 497 F. Supp. 1134 (S.D. Tex. 1980)

Phillips v. Brock, 652 F.Supp. 1372 (D. MA. 1987)

Polaski v. Heckler, 739 F.2d 1320 (8th Cir. 1984)

Stieberger v. Bowen, 801 F.2d 29 (24d Cir. 1986)

Thomas v. Johnston, 557 F.Supp. 879 (W.D. Tex. 1983)

Underwood v. Hills, 414 F.Supp. 526 (D.D.C. 1976)

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975)

Rules:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (a)

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2)

Statutes:

28 U.5.C.'§S 1331

Medicaid Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396-1396s

$i

throughout

throughout

Page:

Federal Publications:

HHS, "Strategic Plan For The Elimination of Childhood Lead

Poisoning", February 1991, page 18 4

Section 5123.2.D.1 of the State Medicaid Manual 10

iv

* 9

Plaintiffs have moved for certification of two classes: a

national class of Medicaid-EPSDT children for the claims against

the USA and a statewide class of Medicaid-EPSDT children for the

claims against the state defendant, Raiford. Plaintiffs’ argument

and demonstration of compliance with Local Rule 10.2 is set out

separately for each class.

National class

Plaintiffs seek a national class to assert the claims under

the Medicaid Act that require the use of a blood lead level test

that is appropriate for age and risk factors.

Local Rule 10.2 (1) appropriate Rule 23 sections

Plaintiffs asset that the national class is authorized by

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a) and 23(b)(2). The 23(a) requirements are

discussed in the following sections. The 23(b)(2) requirement is

met by the fact that the USA sanctions, supports, allows, and

finances the use of the EP test as a lead poisoning screening

device throughout the country and as a matter of conscious

policy.

The USA implements the requirements of the Medicaid Act

through regulations and non-regulatory guidelines issued to the

states. The primary non-regulatory guideline is the HCFA "State

Medicaid Manual". The pre-9/19/92 State Medicaid Manual stated

"In general, use the EP test as the primary screening. Perform

venous blood lead measurements on children with elevated EP

levels." The amendments to the State Medicaid Manual, that took

effect on Sept. 19, 1992 continue to sanction the use of the EP

test as the primary screening test for lead poisoning in young

children throughout the country. E.g. "States continue to have

the option to use the EP test as the initial screening blood

test." These directions apply to each state in the union and to

each child in each state. The USA’s implementation of a national

policy makes injunctive relief appropriate for the class as a

whole. Califano v. Yamasaki, 442 U.S. 682, 702 (1979); Fed. R.

Civ. P. 23(b)X2)-

The USA may argue that national class certification is not

necessary because, should the USA lose, it will, or may, choose

to follow the directive of the court irregardless of whether or

not there is a national class. This policy of acquiescence in a

judicial decision it did not like would be unusual for the USA.

The executive branch consistently insists on the existence of

some right to be free from the dictates of the law as declared

even by the Circuit Courts of Appeals within the jurisdiction of

those Courts of Appeals. Johnson v. United States Railroad

Retirement Board, 969 F.2d 1082 (D.C. Cir. 1992). The U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, the agency directly

involved in this litigation, has been one of the executive

agencies most insistent on its alleged right to disobey the law

as interpreted by the lower courts. Hyatt v. Sullivan, 899 F.2d

329 (4th Cir. 1990); Stieberger v. Bowen, 801 F.2d 29, 36-37 (2d

Cir. 1986); Polaski v. Heckler, 739 F.2d 1320, 1322 (8th Cir.

1984); Lopez v. Heckler, 725 F.2d 1489 (9th Cir. 1984) vacated on

other grounds and remanded, 469 U.S. 1082 (1984); Childress v.

* ®

Secretary of HHS, 679 F.2d 623, 630 (6th Cir. 1982).

Injunctive relief with respect to the class as a whole is

necessary in order to provide the relief to which the class is

entitled. Plaintiffs seek the following substantive relief

against the USA:

a. a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunc-

tion enjoining the USA, through the HCFA, from supporting,

allowing or financing the States’ use of the EP test as an appro-

priate screening test for lead poisoning and ordering defendant

USA, through the HCFA, to require the States to use a blood lead

level test as a screening device for childhood lead poisoning,

b. a permanent injunction that:

(1) contifues the relief granted by the TRO and prelim-

inary injunction,

(2) enjoins the operation and effect of any regulations

or guidelines which allow for the use of and the compensation for

EP tests to test for lead poisoning instead of blood lead level

tests,

(3) orders the publication of and enforcement of

regulations and guidelines requiring the States to use blood lead

tests and requiring the States to retest, using blood lead tests,

each Medicaid eligible child for whom the States have used an EP

test instead of a blood lead test and compensating the States for

the retests.

If the national class is certified, then the legal basis for

the complete relief requested will undoubtedly be present. Absent

* ®

national class certification, there might be some questions about

some of the relief requested, e.g., the retesting of each child

for whom an EP test has been conducted and relied upon.

Local rule 10.2 (2) specific factual allegations and common

questions

1. The number or approximate number of class members -

There are and have been more than several million children

residents of the United States who are eligible for Medicaid and

the USA’s EPSDT program. As of 1989 there were 10 million total

Medicaid-EPSDT eligible children in the country. "EPSDT is a

comprehensive prevention and treatment program available to

Medicaid-eligible persons under 21 years of age. In 1989, of the

10 million eligible.persons, more than 4 million received initial

or periodic screening health examinations...Screening services,

defined by statute, must include a blood lead assessment ‘where

age and risk factors indicate it is medically appropriate.’."

HHS, "Strategic Plan For The Elimination of Childhood Lead

Poisoning", February 1991, page 18.

The class of all these persons is so numerous that joinder

of all these persons is impractical. Joinder of millions of

children is not feasible because of the number. The geographic

dispersion and poverty status of these children makes joinder

even more impractical. Lynch v. Rank, 604 F.Supp. 30, 36 (N.D.

Ca. 1984); Mertz v. Harris, 497 F. Supp. 1134, 1138 (S.D. Tex.

1980).

2. The definition of the class -

The national class is defined to be all Medicaid-eligible

4

children located in the United States of America.

National classes are commonly used in matters of national

policy involving social welfare programs. "The scope of injunc-

tive relief is dictated by the extent of the violation and not by

the geographical extent of the plaintiff class." Califano, 442

U.s.. 682, 702 (1979); Phillips v. Brock, 652 F.Supp. 1372, 1377

(D. Md. 1987); Kuenz v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 104 F.R.D.

474 (D. Mo. 1985); Underwood v. Hills, 414 F.Supp. 526, 528

(D.D.C. 1976}.

Where the class is defined by reference to the defendant’s

alleged nationwide practices, nationwide certification is proper.

Orantes—-Hernandez v. Smith, 541 F.Supp. 351, 366 (C.D. Ca. 1982).

3.h deserippion of the distinguishing and common character-

istics of class members in terms of geography, time, common

financial incentives, etc. -

The common characteristic for the class is that they are all

eligible for the Medicaid-EPSDT program because of their age and

poverty. They are more likely to be at risk of childhood lead

poisoning because of their age and poverty. While they are in

different states, the federal policy complained of is common to

each state.

4. The questions of law and fact claimed to be common to the

class -

The common question of law is the central question of law in

the case - does the U.S.A.’s continued sanction, support, and

financial assistance for the EP test violate the requirements of

the federal Medicaid Act. The determination of whether or not

the EP test meets the statutory requirement that each child be

given a blood lead level test appropriate for age and risk

factors is the same whether the child lives in Alaska or Texas.

This question of law is sufficient to support class certifica-

tion. Califano, 442 U.S. 682, 702 (1979).

Local rule 10.2 (3) adequate representation

1. Typicality

Plaintiffs’ claims involve proof of the same set of

facts on their own behalf as they would have to prove on behalf

of the class. Plaintiffs’ interests in proving liability by

defendant United States are the same as the class members’

interests. :

2. Fair and adequate representative of the class

There is no conflict between the plaintiffs and the class.

Plaintiffs seek the same injunctive relief on their own behalf as

is sought on behalf of the class.

There is no conflict of interest in terms of compensation of

plaintiffs’ counsel. No plaintiff has paid or will pay any

attorney’s fee in this case. Plaintiffs’ counsel are providing

representation solely on the basis that if successful, attorney’s

fees will be sought from court awarded, statutory fees and

litigation expenses from defendants. A term of the retainer

agreement with the name plaintiffs, however, is that plaintiffs

will not accept a settlement that does not provide for reasonable

attorneys fees and costs for its attorneys. Plaintiffs’ counsel

have the same interest in obtaining relief for the class members

as they do for the plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs’ counsel Michael M. Daniel is an experienced

civil rights attorney with prior experience litigating claims on

behalf of poor persons and class members on a wide variety of

issues. -

3. Financial responsibility to fund the action

Plaintiffs’ counsel Michael M. Daniel, P.C. has demonstrated

the financial responsibility to advance the funding for substan-

tial civil rights actions such as this case in a wide array of

matters involving housing, voting rights, and environmental

issues.

Local rule 10.2 (4) jurisdictional amount

There is no jurisdictional amount in the federal statute

upon which jurisdiction is grounded in this case, 28 U.S.C. §

1331.

Local rule 10.2 (5) notice to the class

Notice is not necessary at this juncture since it is a Rule

23(b) (2) class that is seeking injunctive relief from the defen-

dant.

Local rule 10.2 (6) class discovery

Plaintiffs see no need for further discovery on their part

for class certification unless defendant U.S.A.’s opposition to

the class certification raises issues needing discovery.

Local rule 10.2 (7) plaintiffs attorneys fees

No plaintiff has paid or will pay any attorney’s fee in this

case. Plaintiffs’ counsel are providing representation solely on

the basis that if successful, attorney’s fees will be sought from

court awarded, statutory fees and litigation expenses from

defendants. A term of the retainer agreement with the name

plaintiffs, however, is that plaintiffs will not accept a settle-

ment that does not provide for reasonable attorneys fees and

costs for its attorneys.

Other litigation

The plaintiffs are aware of no other pending litigation

anywhere in the country challenging the U.S.A.’s use of the EP

test in the Medicaid-EPSDT program.

Standing of plaintiffs to bring a national class action

The name plaintiffs have suffered injury in fact. They are

eligible for the Medicaid-EPSDT program. They were screened for

lead poisoning with the challenged EP test which failed to detect

plaintiffs’ lead poisoning. They are still participants in the

EPSDT program and still subject to the challenged EP test.

The injury suffered is distinct and palpable in that it is

not an undifferentiated, generalized grievance against the

government. Being subjected to the use of the EP test affects

these plaintiffs differently from the citizenry at large. The

injury has and will concretely harm plaintiffs by subjecting them

to undiagnosed and untreated lead poisoning.

The U.S.A’s failure to require the states to use a blood

lead level test appropriate for age and risk factors is a dis-

tinct causal factor in plaintiffs’ injuries. If the U.S.A. is

required to withdraw its support for the EP test and require the

use of blood lead level test, then plaintiffs’ injuries will be

remedied. They will receive a blood lead level test that allows

for diagnosis and treatment of lead poisoning. Warth v. Seldin,

422 U.S. 490 (1975).

Discretion of the Court

Certifying a national class is within the discretion of the

district court. The certification of this class is an efficient

and expeditious means of reaching a final and binding resolution

of the issue in this case. The national class would serve the

anti-proliferation of litigation policy behind the class action

rules. The focus of the litigation is narrow and revolves around

a discrete issue. :

The national class should be certified. Califano, 442 U.S.

682, 702 (1979).

Statewide class

Plaintiffs seek a statewide class to assert the claims under

the Medicaid Act that requires the state defendant Raiford to use

of a blood lead level test that is appropriate for age and risk

factors in the Texas EPSDT program.

Local Rule 10.2 (1) appropriate Rule 23 sections

Plaintiffs contend that the statewide class is authorized by

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a) and 23(b)(2). The 23(a) requirements are

discussed in the following sections. The 23(b) (2) requirement is

met by the fact that defendant Raiford continues to allow the use

of the EP test to test for lead poisoning in the Texas EPSDT

® #

program in violation of the Medicaid Act.

The State of Texas participates in the federal Medicaid

program and has established the Texas Department of Human Servic-

es (TDHS) which provides medical services to low-income persons

through reimbursement of health care providers for such services.

The federal requirements of the Medicaid Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396-

1396s, are binding on the State of Texas. The class members are

children eligible for Medicaid. Many of these children, because

of their age and the environmental conditions in many areas of

the State, are at risk or high risk of lead poisoning.

Rather than comply with the Medicaid requirements of lead

blood level assessment and treatment for the lead exposure

discovered, defendant Raiford has deliberately and willfully

chosen to disobey that mandate. Instead of testing for blood lead

level, defendant uses a laboratory test to detect levels of

Erythrocyte Protoporphin (EP). Defendant Raiford’s continued use

of the EP test is inexplicable on any defensible grounds.

Rather than comply with the statute’s mandate that the blood

lead level assessment be done in accord with appropriate age and

risk factors, defendant Raiford has willfully and deliberately

chosen to use age as the primary factor in lead level assessment.

The federal Health Care Financing Administration released a

report dated July 12, 1991 that reviewed defendant’s compliance

with the risk assessment requirement of the statute. The report

found: "The State has not established risk factors (other than

age) to assist providers in determining whether it is appropriate

10

to perform a blood lead level test. It has established an age

factor. ..however, according to Section 5123.2.D.1 of the State

Medicaid Manual, States should also consider environmental

aspects when establishing risk factors." The report recommended

that "The State should require that high blood lead level areas

be taken into consideration when determining risk factors and it

should furnish EPSDT screening providers with a list of these

high risk zones." Defendant Raiford’s August 29, 1991 response

to the HCFA report stated "We agree with the finding". Defendant

Raiford has still not furnished EPSDT screening providers with a

list designating high risk zones for childhood lead poisoning in

the state.

CDC has established a screening schedule for children at

high risk for lead poisoning which starts at six months and

varies throughout childhood depending on the results of the blood

lead tests. Defendant Raiford requires only one screening for

lead poisoning at either 6 months of age or once between the ages

of 9 months and 20 years if not given at six months.

Rather than comply with the statutory mandate to provide

treatment for lead poisoning discovered in the screening process,

defendant Raiford ignores the accepted CDC guidelines for medical

and public health interventions once lead poisoning is discov-

ered. For example, the plaintiff children’s files are empty of

any intervention other than a referral to the City of Dallas for

a follow up. Defendant Raiford does not provide individual case

management including nutritional and educational interventions,

11

more frequent screening, environmental investigations (including

a home inspection) and remediation for children with blood lead

levels of 15-19 ug/dL.

Injunctive relief with respect to the class as a whole is

necessary in order to provide the relief to which the class is

entitled. Plaintiffs seek the following substantive relief

against defendant Raiford:

a. a temporary restraining order enjoining defendant from

the use of the EP test statewide as a blood lead level screening

procedure and requiring the defendant to use the blood lead level

test statewide as part of the EPSDT program,

b. a preliminary and permanent injunction requiring Mr.

Raiford to: J

(1) continue the temporary relief,

(2) declare West Dallas a geographic area of high risk for

children for lead poisoning and notify all EPSDT providers that

eligible children that live and have lived in West Dallas must be

given lead blood level assessments.

(3) declare other geographic areas of the State of Texas

that have a risk of lead contamination as areas of high risk for

children for lead poisoning and notify all EPSDT providers that

eligible children that live in those high risk areas and have

lived in those areas must be given lead blood level assessments.

(4) give effective notice and outreach to all EPSDT eligible

children who live in West Dallas or other high risk areas of the

State of Texas or have lived in West Dallas or other high risk

12

areas in the state of the availability of the blood lead screen-

ing and treatment.

(5) re-test, using the blood lead level test, each person in

the class for whom the EP test was given in the past,

(6) implement a case management program to ensure that all

children eligible for the screening receive it and that all

necessary medical treatment is provided to the children for whom

the screening indicates a lead poisoning related health risk. The

screening, the schedule for screening and the treatment provided

should all be conducted pursuant to the U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease

Control guidelines.

If the statewide class is certified, then the legal basis

for the complete relief requested will undoubtedly be present.

Without statewide class certification, there might be some ques-

tions about some of the relief requested, e.g.,the retesting of

each child in the state for whom an EP test has been conducted

and relied upon and the designation of areas of the state as high

risk zones for childhood lead poisoning.

Local rule 10.2 (2) specific factual allegations and common

questions

1. The number or approximate number of class members -

There are and have been more than several thousand children

residents of the State of Texas who are eligible for Medicaid and

defendant Raiford’s EPSDT program. As of 1991 there were at

least 768,163 total Medicaid eligible children in the State of

13

Texas. The class of all these persons is so numerous that

joinder of all these persons statewide is impractical.

2. The definition of the class -

The statewide class is defined to be all Medicaid-eligible

children located in the state of Texas.

Statewide classes are common in programs involving the

social welfare of children. In Thomas v. Johnston, the Texas

district court conditionally certified a class of children

Medicaid recipients for their claims against the TDHS commission-

er in order to grant the requested preliminary relief. 557

F.Supp. 879, 916 (W.D. Tex. 1983).

3. A description of the distinguishing and common character-

istics of class nenbers in terms of geography, time, common

financial incentives, etc. =

The common characteristic for the class is that they are all

eligible for defendant Raiford’s Medicaid-EPSDT program because

of their age and poverty and location in Texas. They are more

likely to be at risk of childhood lead poisoning because of their

age and poverty.

4. The questions of law and fact claimed to be common to the

class -

The common question of law is the state defendant Raiford’s

failure to screen Texas-EPSDT children with a blood lead level

test in accordance with the Medicaid Act. The question of law is

common to all EPSDT children in the State of Texas regardless of

whether they live in an area of high risk for childhood lead

14

poisoning or not. This question of law is sufficient to support

class certification.

Local rule 10.2 (3) adequate representation

1. Typicality

Plaintiffs’ claims involve proof of the same set of

facts on their own behalf as they would have to prove on behalf

of the class. Plaintiffs’ interests in proving liability by

defendant Raiford are the same as the class members’ interests.

2. Fair and adequate representative of the class

There is no conflict between the plaintiffs and the class.

Plaintiffs seek the same injunctive relief on their own behalf as

is sought on behalf of the statewide class.

There is no conflict of interest in terms of compensation of

plaintiffs’ counsel. No plaintiff has paid or will pay any

attorney’s fee in this case. Plaintiffs’ counsel are providing

representation solely on the basis that if successful, attorney’s

fees will be sought from court awarded, statutory fees and

litigation expenses from defendants. A term of the retainer

agreement with the name plaintiffs, however, is that plaintiffs

will not accept a settlement that does not provide for reasonable

attorneys fees and costs for its attorneys. Plaintiffs’ counsel

have the same interest in obtaining relief for the class members

as they do for the plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs’ counsel Michael M. Daniel is an experienced

civil rights attorney with prior experience litigating claims on

behalf of poor persons and class members on a wide variety of

15

issues.

3. Financial responsibility to fund the action

Plaintiffs’ counsel Michael M. Daniel, P.C. has demonstrated

the financial responsibility to advance the funding for substan-

tial civil rights actions such as this case in a wide array of

matters ‘involving housing, voting rights, and environmental

issues.

Local rule 10.2 (4) jurisdictional amount

There is no jurisdictional amount in the federal statute

upon which jurisdiction is grounded in this case, 28 u.s.c. §

1331.

Local rule 10.2 (5) notice to the class

Notice is not Necessary at this juncture since it is a Rule

23(b) (2) class that is seeking injunctive relief from the defen-

dant.

Local rule 10.2 (6) class discovery

Plaintiffs see no need for further discovery on their part

for class certification unless defendant Raiford’s opposition to

the class certification raises issues needing discovery.

Local rule 10.2 (7) plaintiffs attorneys fees

No plaintiff has paid or will pay any attorney’s fee in this

case. Plaintiffs’ counsel are providing representation solely on

the basis that if successful, attorney’s fees will be sought from

court awarded, statutory fees and litigation expenses from

defendants. A term of the retainer agreement with the name

plaintiffs, however, is that plaintiffs will not accept a settle-

16

ment that does not provide for reasonable attorneys fees and

costs for its attorneys.

Other litigation

The plaintiffs are aware of no other pending litigation in

the State of Texas challenging the state defendant Raiford’s use

of the EP test in the Medicaid-EPSDT program.

Standing of plaintiffs to bring a statewide class action

The name plaintiffs have suffered injury in fact. They are

eligible for the Texas Medicaid-EPSDT program. They were

screened for lead poisoning with the challenged EP test which

failed to detect plaintiffs’ lead poisoning. They are still

participants in the Texas EPSDT program and still subject to the

challenged EP toni

The injury suffered is distinct and palpable in that it is

not an undifferentiated, generalized grievance against the state

defendant. Being subjected to the use of the EP test affects

these plaintiffs differently from the citizenry at large. The

injury has and will concretely harm plaintiffs by subjecting them

to undiagnosed and untreated lead poisoning.

Defendant Raiford’s failure to require the states to use a

blood lead level test appropriate for age and risk factors is a

distinct causal factor in plaintiffs’ injuries. If the requested

relief is granted for the statewide class, then plaintiffs’

injuries will be remedied. They will receive a plocd lead level

test that allows for diagnosis and treatment of lead poisoning.

Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975).

17

Discretion of the Court

Certifying a statewide class is within the discretion of the

district court. The certification of this class is an efficient

and expeditious means of reaching a final and binding resolution

of the issue in this case. The statewide class would serve the

anti-proliferation of litigation policy behind the class action

rules.

The statewide class should be certified.

Respectfully submitted,

MICHAEL M. DANIEL, P.C.

3301 Elm Street

Dallas, Texas 75226-1637

(214) 939-9230 (telephone)

Wo csimile)

By: m 4

Michael M. Daniel a

State Bar No. 05360500

By: na EE Le Hai

Laura B. Beshara

State Bar No. 02261750

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFF

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a true and correct copy of the above document

was served upon counsel for defendants by being Plaged in the

IR first class postage prepaid, on the /{/™ day of

z ol 1992.

rn 5 Erba

~~ Laura B. Beshara

18