Simmons v Brown Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1975

78 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simmons v Brown Reply Brief for Appellants, 1975. 923bd36c-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ab71abe1-6a52-446e-8952-7563aa17ccd6/simmons-v-brown-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

/

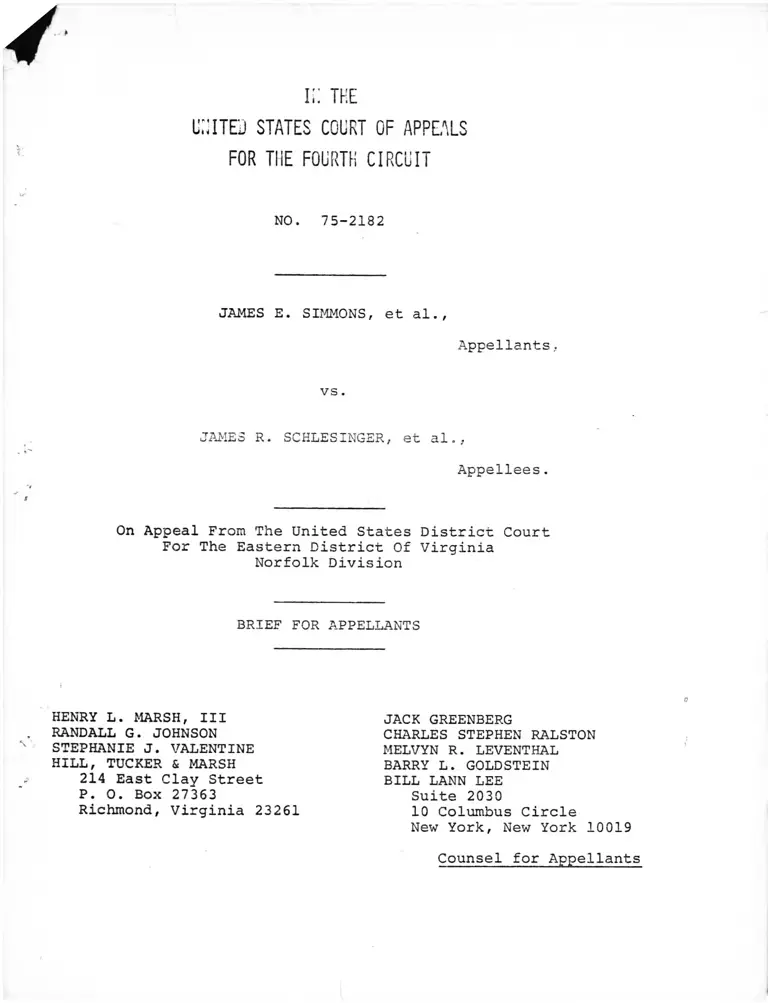

i;: t h e

U;:iTE'J STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

tr*

NO. 75-2182

JAMES E. SIMMONS, et al.,

Appellants,

v s .

JAMES R. SCHLESINGER, et al..

Appellees.

I

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Virginia

Norfolk Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

HENRY L. MARSH, III

. RANDALL G. JOHNSON

STEPHANIE J. VALENTINE

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

P. 0. Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

*

TABLE OF CONTENTS

iii

1

2

9

9

Page

9

13

13

14

16

18

24

Introduction -------------------------------------- 24

I. The District Court Erred In Denying Federal

Employees The Right To Maintain A Class

Action Pursuant To Rule 23(b)(2) Fed. R. Civ.

Pro. On Behalf Of Other Similarly Situated

Employees----------- 27

A. Class Actions Provided For In The Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure Are Not Precluded

Or Limited In Any Way By The Statutory

Language Of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 34

1. Rule 23(b)(2) Fed. R. Civ. Proc. -------- 34

2. The Statutory Language of 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-16 ----------------------------- 36

B. In 1972 Congress Expressly Disclaimed Any

Intent To Preclude Or Limit Class Actions

To Enforce Title V I I ---------------------- 44

II. The District Court Erred In Denying Federal

Employees The Right To Prepare For Trial Of

The Individual Claims By Conducting Discovery

Calculated To Uncover Broad And Systemic

Patterns And Policies Of Discrimination ----

TABLE OF CITATIONS ----------------------------------

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED -----------------------

STATEMENT OF THE CASE-------------------------- -

STATEMENT OF FACTS ----------------------------------

Historic Racial Discrimination at NARF -----------

1. Trial Testimony Concerning Job Histories

Of Black Employees-------------- 1--------

2. NARF EEO Affirmative Action Plans -------

Patterns and Policies Of Employment Discrimination

1. 1971 and 1972 ---------------------------

2. 1973 -------------------------------------

Claims of The Named Plaintiffs ------------------

ARGUMENT --------------------------------------------

49

»

A. The District Court Simply Ignored All

Applicable Precedent In Denying Discovery

Calculated To Uncover Broad And Systemic

Patterns And Policies Of Discrimination --- 49

B. The District Court Improperly Limited

Plaintiffs' Discovery And Presentation

Of Evidence Of Systemic Discrimination

While Permitting Defendants To Present

Evidence Of Equal Scope ------------------- 52

III. The District Court Failed To Apply

Substantive Title VII Law To The Facts

Presented With Respect To The Individual

Plaintiffs---------------------------------- 54

A. The Evidence Presented To The Trial Court

Conclusively Showed Racial Discrimination — 54

1. Discrepancies Between The GS-5 And GS-7

Registers-------------------- 55

2. Rating Panel Judgment ----------------- 56

3. Administrative Investigation ---------- 59

B. The Statistical Evidence Presented At The

Trial Established A Prima Facie Case Of

Racial Discrimination ---------------------- 60

1. Statistics Presented ------------------ 62

2. Continuing Disparities ---------------- 63

3. Career Advancement Of Plaintiffs ------ 64

4. Rebuttal Evidence ------------------- ;— 65

C. The District Court Considered Improper

Factors In Dismissing Plaintiffs' Action --- 66 1 2 3

1. Good Faith Of Defendants-------------- 66

2. Specific Discriminators------- 68

3. Civil Service Commission Regulations -- 68

CONCLUSION------------------------------------------- 70

ATTACHMENT A ----------------------------------------- la

ATTACHMENT ------------------------------------------- 8a

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(Continued)

Page

»

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

iii

Page

Aetna Ins. Co. v. Kennedy, 301 U.S. 389 (1937)

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, ___ U.S. ___,

45 L .Ed.2d 280 (1975) ---------------------

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ------------------------------------

Barnett v. W. T. Grant Company, 518 F .2d 543

(4th Cir. 1975) ---------------------------

Barrett v. U.S. Civil Service Commission, C.A.

No. 74-1694 (D.D.C., decided December 10,

1975) --------------------------------------

Blue Bell Boots, Inc. v. EEOC, 418 F .2d 355

(6th Cir. 1969) ---------------------------

Boston v. Naval Station, C.A. No. 74-123-N

(E.D. Va., decided November 18, 1974) -----

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F .2d 711

(7th Cir. 1969) ---------------------------

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457

F .2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409

U.S. 982 (1972) ----------- ----------------

Burns v. Thiokol Chemical Corp., 483 F .2d 300

(5th Cir. 1973) ---------------------------

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F .2d 315 (8th Cir.

1971), cert. denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) --

Chisholm v. U.S. Postal Service, 9 EPD 1110,212

(W.D. N.C. 1975) --------------------------

Davis v. Washington, 512 F .2d 956 (D.C. Cir.

1975) --------------------------------------

EEOC v. University of New Mexico, 504 F .2d

1296 (10th Cir. 1974) -------------------- -

Ellis v. NARF, 10 EPD 1(10,422 (N.D. Cal. 1975)

Gamble v. Birmingham Southern Railroad Co.,

514 F .2d 678 (5th Cir. 1975) --------------

Georgia Power Co. v. EEOC, 412 F .2d 462 (5th

Cir. 1969) ---------------------------------

Graniteville Co. v. EEOC, 438 F .2d 32 (45th

Cir. 1971) --------------------------------

Green v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 463 F .2d 337

(8th Cir. 1972), remanded, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ------------------------- -----------

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)

41

26,36,44,66

36,40,41,70

24,27,35,49,

50,54,61,62,

66,67

32.44

33,36

4

45

24,27,50,56,

57,59,61

50,51

58

35

33

33

32.44

64

33

25,33,36,49,

52

58

26,29,36,51,

58,66

401 U.S. 424 (1971)

»

iv

TABLE OF CITATIONS

(Continued)

Page

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323

(D.C. Cir. 1975)----------------------- 25,39

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108

(D.C. Cir. 1975)----------------------- 25,31,44

Hall v. Werthan Bar Corp., 251 F. Supp.

184 (M.D. Tenn. 1966)------ ;----------- 36

Harris v. Nixon, 325 F.Supp. 28 (D. Colo.

1971)----------------------------------- 39

Hodges v. Easton, 106 U.S. 408 (1882)----- 41

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 34

(5th Cir. 1968)------------------------ 35,36,40,45,47

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.

417 F. 2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969)— ;-------- 35,36

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938)--- 41

Keeler v. Hills, H.D. Ga. C.A. C74-2152A,

2309A, decided November 12, 1975)------ 32,44

Roger v. Ball 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir.

1974)----------------------------------- 25,70

Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir.

1965), cert denied, 384 U.S. 929

196 6)----------------------------------- 36,37,38,39

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 83 (4th

Cir. 1971)------------------------------ 60

Local No. 104, Sheet Metal Workers Int'l

Assoc, v. EEOC, 439 F.2d 237 (9th Cir.

1971)----------------------------------- 33

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S. 522 (1972)-- 40

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973)------------------ 1-------------- 6,26,27,40,50,56

Miller v. International Paper Co., 408

F. 2d 283 (5th Cir. 1969)--------------- 45

Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F.2d 960 (5th Cir.

1973) aff'd en banc, 491 F.2d 1093 (5th

Cir. 1974)------------------------------ 24

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974)----- 70

Moss v. Lane Company, Inc., 471 F.2d 853

(4th Cir. 1973)------------------------ 24,27

Motorola Inc. v. McClain, 484 F.2d 1139

(7th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 416 U.S.

936 (1974)------------------------------ 33

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S.

400 (1968)------------------------------ 40

New Orleans Public Service, Inc. v. Brown,

507 F. 2d 160 (5th Cir. 1975)----------- 33,53

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d

496 (5th Cir. 1968)-------------------- 37,38,39,45,47

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public

Utilities Comm., 301 U.S. 292 (1937)----- 41

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co.,

433 F. 2d 4 2 1---- ---------------------- 60,64

V

Parks v. Dunlap, 517 F.2d 785 (5th

Cir. 1975)-------------------------- 25

Petterway v. Veterans Adminstration

Hospital, 495 F.2d 1223 (5th Cir.

1975)-------------------------------- 26

Place v. Weinberger, October Term, 1974

No. 74-116, petition for rehearing

pending.----------------------------- 25

Quarles v. Phillip Morris, Inc., 279

F.Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968)-- 51

Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d

333 (10th Cir. 1975)----------------- ' 24,50,51,53

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971)----------------- 49

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d

348 (5th Cir. 1972)----------------- 56,66,67

Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431

F. 2d 455 (5th Cir. 1970)------------ 32,40,44

Sharp v. Lucky, 252 F.2a 910 (5th Cir.

1958)-------------------------------- 37,39

Sibbach v. Wilson & Co., 312 U.S.' 1

(1941)------------------------------- 34

Sylvester v. U.S. Postal Service, 9 EPD

<[10,210 (S.D. Tex. 1975)------------ 35

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry.

Co., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972)--- 25,49

United States v. Dillon Supply Co.,

429 F. 2d 800 (4th Cir. 1970)-------- 50,52,56

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Company, 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971),

cert. denied, 406 U..S. 906 (1971)--- 57,58

United States v. United Ass'n of

Journeymen, Etc., U. No. 24, 364

F.Supp. 808 (D.N.J. 1973)----------- 58

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345

U.S. 629 (1953)--------------------- 64

Weinberger v. Salfi, 42 USLW 4985

(decided June 26, 1975)-------

TABLE OF CITATIONS

(continued)

Page

38

VI

Other Authorities

Executive Order 11473 ------------------------- 1/2,33

Executive Order 9980 -------------------------- 2

Executive Order 10590 ------------------------- 2

Executive Order 11246 ------------------------- 2

Executive Order 10577 ------------------------- 2

Executive Order 11141 ------------------------- 2

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 23(b)(2)---------- 1,2,33,34,

35,41,42,44

Fifth Amendment to the United States

Constitution --------------------------------- 1,2,33

Proposed Amendments to Rules of Civil

Procedure, 39 F.R.D. 69 --------------------- 34,35

Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor

and Public Welfare, Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972 (Comm. Print 1971) ---------------------- 29,30,33,46,

47,48,68,69

5 CFR §713.211 et ^e^. ---------------------- 27,28

5 CFR §713.251 ------------------------------- 5,28,42,43

5 CFR §713.216(a) (1974) --------------------- 32

5 U.S.C. §7151 ----------------------------- 1,2,33

5 U.S.C. §7154 ----------------------------- 2,33

5 U.S.C. §5596 ----------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §1292 ----------------------------- 7

28 U.S.C. §1331 (a) ---------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §1343 (4) ---------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §L36 1 ----------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §1364 (a) (2) -------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §2201 ----------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §2202 ----------------------------- 2,33

28 U.S.C. §2072 ----------------------------- 34

28 U.S.C. §2073 ----------------------------- 34

42 U.S.C.- §405 (g) ---------------------------- 38

42 U.S.C. §406 (g) ---------------------------- 38

42 U.S.C. §706 (a)---- .------------------------ 46

42 U.S.C. §706 (d) ----------------------------- 46

42 U.S.C. §706 (h) ----------------------------- 45

42 U.S.C. §706 (f) ----------------------------- 48

42 U.S.C. §706 (k) ----------------------------- 42 * * * * * 48

Page

Other Authorities

(Continued)

Page

42 U.S.C. §2000a et_ seq. ---------------------- 37

42 tf.S.C. §2000e-5 (f) (1) ---------------------- 43

47 U.S.C. §2000e-16 et seq. passim ------------ 1,2,33,34,36,38,39,41,

42,44

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (1) --------------------- — 39

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (a) ----------------------- 28,51

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (c) ----------------------- 39,48

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (d) ----------------------- 43

42 U.S.C. §1983 — ---------------------------- 37

vii

118 Cong. Rec. 7169 , 7566 ----* 43

16

employees (6 of 68) were in grades higher than GS-10 compared to

24% of total GS employees (210 of 863) and 26% of white GS

employees (204 of 795). This pattern was consistent from

department to department.

Although the 1972 statistics are incomplete, the

available 1972 categories are comparable to their equivalent

1971 categories.

i6_/

2. 1973

While 21% of all NARF employees in 1973 held GS

positions (916 of 4444) and 24% of all white employees (837 of

3462), only 8% of all black NARF employees held GS jobs (79 of

982). Similarly, while 22% of all NARF employees were black

(982 of 4444) and 26% of all non-GS employees were black (903

of 3528), only 9% of all NARF GS employees were black (79 of 916).

These statistics reveal little change from the situation in 1971

16/

The 1973 tables are dated 30 November 1973 and thus

reflect NARF employment patterns at the time of the filing of

the administrative complaint of discrimination on December 3.

The 1973 tables show (a) number and percent of black and total

GS employees by department and level; (b) number and percent of

black and total Regular Supervisory or WS employees by department

and level; (c) number and percent of black and total Production

Facilitating or WD, WN, WB, WX and WY employees by department

and level; and (d) number and percent of black and total Regular

Nonsupervisory or WG employees by department and level. The

three non-GS categories although organized somewhat differently

are equivalent to the single 1971 and 1972 non-GS or ungraded

category. The 1973 tables demonstrate the same consistent

pattern of disproportionate concentration of black employees at

lower job levels revealed in the 1971 and 1972 tables.

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 75-2182

JAMES E. SIMMONS, et al.,

Appellants,

v s .

JAMES R. SCHLESINGER, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District Of Virginia

Norfolk Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS * 9

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED

In a civil action brought by black federal employees

pursuant to §717 of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

9

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16, the Fifth Amendment, 5 U.S.C.

§7151, and Executive Order 11478, to redress racial discrimina

tion in agency employment practices:

1. Whether the district court may deny federal

employees the right to maintain a class action

pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2), Fed. R. Civ. Pro.,

on behalf of other similarly situated black

employees?

2. Whether the district court may deny federal

employees the right to prepare for trial of

the individual claims by conducting discovery

calculated to uncover broad and systemic

patterns and policies?

3. Whether the district court properly applied

recognized principles of substantive Title VII

law to the claims of the individual plaintiffs?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On June 12, 1974, after unsatisfactory agency resolu

tion of the charge of racial discrimination filed by plaintiffs

James E. Simmons, Edward S. Ferebee, Melvin L. Holloman and

Wilton L. Day, with the Naval Air Rework Facility in Norfolk,

Virginia (hereinafter "NARF"), this suit for declaratory and

injunctive relief against racially discriminatory employment

practices at the NARF under 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16, the Fifth

Amendment, 5 U.S.C. §7151, and Executive Order 11478 was

brought as a class action pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2), Fed. R. Civ.

_ 2_ /

Pro. (App. 4). The complaint charges defendants James R.

Schlesinger, Secretary of Defense; John Warner, Secretary of the

Navy; and Captain E. F. Shine, Jr., NARF Commander, with systemic

2

j y

This action was also brought under 5 U.S.C. §7154,

E.O. 9980, E.O. 10590, E.O. 11246, E.O. 10577, and E.O. 11141.

_2_/

Jurisdictional bases cited were 42 U.S.C. 2000e-16(c)

and (d); 42 U.S.C. 2000(e)-5(f)-(k); 5 U.S.C. §§7151 and 7154;

28 U.S.C. §§1331(a), 1343(4), 1361, 1364(a)(2), 2201 and 2202;

and 5 U.S.C. 5596.

3

discrimination against black persons in the areas of, inter alia,

hiring practices; denial of promotions; denial of assignments

of supervisory duties; utilization of a system of promotion

which relies on unvalidated subjective recommendations of

supervisors; unequal treatment by supervisors' including more

stringent performance standards and more severe disciplinary

penalties; refusal to promote and assign appropriate duties to

those who successfully complete training programs; assignment

and transfer into work groups and job categories with low

advancement potential; refusal to develop and implement

effective affirmative action programs; discouraging filing of

discrimination complaints; failure to discipline or reprimand

supervisors for taking discriminatory actions; failure to

terminate effects of past and present discrimination; and

failure to promote the named plaintiffs. A motion was filed

on August 23, 1974 to compel defendants to answer (App. 1);

J _J_/defendants filed their answer on November 22nd (App. 1).

Meanwhile, Plaintiffs' First Interrogatories to Defendant

Captain E. F. Shine, Jr., were filed August 23, 1974. (App. 14-52).

The interrogatories request information and statistical data

concerning, inter alia, organizational structure, recruitment

and hiring practices, assignment practices, training and

apprenticeship programs, temporary assignment practices,

_3/

The complaint, which originally had also alleged

discrimination on the basis of sex, was amended to remove all

such references and allegations December 4, 1974 (App. 2).

4

discrimination complaint resolution practices, racial discrimina

tion in departments, grades and jobs; promotion and transfer

practices; and evaluation and rating practices. Plaintiffs

moved to compel answers to interrogatories October 18, 1974

(App. 53-54).

On November 22nd, a pretrial conference was held

which resulted in an order setting a final pretrial conference

date of April 18, 1975 and a trial date of May 13, 1975

(App. 1-2). Defendants were also required to file their

objections to plaintiffs' interrogatories by December 6, 1975

and a hearing was set for December 13th on defendants'

objections and plaintiffs' motion to compel answers. The

next day, plaintiffs moved the court to require defendants

to immediately commence preparation of answers to plaintiffs'

interrogatories and to fix January 1, 1975 as the date for

, _ , A_/defendants to answer the interrogatories (App. 55-58).

Defendants filed a response December 5, 1974, stating that "the

government will not respond to the interrogatories because they

pertain solely to matters relating to a class action. These

AJ

The motion recited that, inter alia, defendants

had made no response to plainiffs' interrogatories in the

time specified by the local rules for objections and the

time specified by the Federal Rules for answers; the potential

class includes more than 1,000 employees and the interrogatories

are extensive; plaintiffs' counsel had requested a trial date in

the fall or late summer of 1975 so as to permit a discovery period

of 3.t least eight months, but May 13th was the latest possible

date plaintiffs could secure at the pretrial conference; and

defendants objections that plaintiffs are not entitled to a trial

novo had already been rejected by the district court in another

federal employee Title VII action, Boston v. Naval Station, and

that plaintiffs' right to maintain Title VII class actions has

long been recognized.

interrogatories are directed toward issues that were not

exhausted in the administrative process under 5 CFR 713.251

and thus cannot be advanced in this litigation." App. 59.

On December 3, 1974, defendants moved to dismiss for

lack of subject matter jurisdiction and for summary judgment

(App. 2). Defendants' supporting memoranda argued that as a

matter of law only a review of the administrative record (rather

than a trial de novo) was required, and that a class action

cannot be maintained because plaintiffs did not invoke the

procedures of 5 CFR §713.251 which permit allegations of

class-type discrimination to be raised in the administrative

process (App. 2).

The district court issued an Opinion and Order January

20, 1975 on questions concerning the discovery motions and

whether a class action could be maintained (App. 61). The

district court framed the issues as follows:

"Plaintiffs have propounded numerous interrogatories

to defendants. The great majority of the interrogatories

deal with questions and issues which would only pertain

if this action proceeds as a class action. Defendants

raise numerous objections to these interrogatories. It

therefore seems appropriate to deal with these issues

as a whole. For until the action is directed or ordered

to proceed as a class action the great majority of the

interrogatories will not be relevant (App. 63).

The court went on to hold (1) that named plaintiffs "are

limited in this case to raising-those issues presented in their

administrative proceedings because they will not have exhausted

administrative remedies as to other issues" and (2) "Hence, it

is quite apparent that defendants should not be required to

answer all the interrogatories heretofore filed" (App. 65-66).

5

6

Counsel were to confer on the interrogatories and a hearing

could be requested as to those interrogatories the parties were

unable to agree on.

Counsel did confer on the interrogatories February 20,

1975, but were unable to arrive at any agreement. Thereafter,

on April 11th, plaintiffs moved, without opposition, for a con

tinuance of the May 13th trial date (App. 68). The motion states

that additional time for proper discovery is necessary because of

the delay in discovery in this proceeding and the workload of

plaintiffs' counsel in several previously scheduled employment

discrimination class actions. The same day, a Motion To Recon

sider Order Denying Class Action And Motion To Compel The

Defendants To Answer Interrogatories was filed (App. 70). The

motion recites, inter alia;

5. Plaintiffs assert that they are entitled to

have this litigation proceed as a class action through

the discovery stages at the least according to

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 (1973). In

restraining the discovery process, plaintiffs

cannot obtain the necessary information from the

defendants which could demonstrate that the employment

and promotion policies practiced by defendants

discriminate against blacks as a class and that a class

action is proper. The information requested can be

obtained only from defendants. 6

6. Plaintiffs have complied with all administrative

and statutory prerequisites for maintaining this suit.

Because plaintiffs are not allowed to raise class

issues during the administrative process, their

opportunity to raise certain issues is provided only by

pursuing this class action in the Federal Courts. It

is well established that class actions are particularly

suited where violations of civil rights are involved.

(App. 71).

7

Attached to plaintiffs' supporting memorandum were Civil Service

Commission documents on the inability of federal employees to

_5_/

raise class issues in the administrative process (App. 3).

The scheduled final pretrial conference of April 18, 1975

was held and an order on final pretrial conference was

issued (App. 79).

On April 23, 1975, the district court denied all the

pending motions (App. 77). The lower court stated:

"This case is scheduled for trial May 13th. The

denial of the motion to proceed as a class action and

not to grant a de novo trial was covered by written

order of January 20th. Permitting this case to now

proceed as a class action would necessitate changing

the date of trial. The named plaintiffs are entitled

to have their cases heard promptly. The same applies

to a renewal of the request to require defendants to

answer the numerous interrogatories propounded. The

case will proceed to trial May 13, 1975. (App. 77-78).

On April 25th, plaintiffs filed notice of appeal to this

court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292 from the April 23rd order

(App. 95) and an accompanying motion to stay the proceedings

pending appeal (App. 97). The appeal was docketed No. 75-8162

The stay motion was denied May 9th (App. 99), and the interlocutory

appeal subsequently withdrawn May 13th (App. 99a).

Dissatisfied with information being supplied by

defendants informally on the individual claims, plaintiffs'

A / The district court in a letter dated April 11,

1975 responded that "The court will not change its ruling

with respect to the question of a class action and the final

pretrial conference and trial will proceed as scheduled."

Thereupon, plaintiffs filed a motion for an interlocutory

appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292(b) on the class action and

discovery questions (App. 73).

counsel on May 8, 1975, requested a subpoena requiring

Captain Shine and the Civilian Personnel Officer to appear

May 13th with copies of documents concerning promotion to

the particular GS levels at issue in the individual claims

of named plaintiffs (App. 1108). In response, defendants

filed a Motion For Protective Order Under Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure 26(c) opposing the production of the subpoenaed

documents with an attached affidavit of the Civilian Personnel

Officer on May 12th (App. 3a). The motion recited that (1)

the material sought pertains to the class action; (2) plaintiffs'

counsel have been furnished with available information

regarding the individual lawsuit; and (3) producing the

subpoenaed personnel.folders would violate the right to

privacy. The court withheld any ruling on the subpoena (Tr. 442-

457). Accordingly, the great bulk of the documents were not

produced.

Trial of the individual claims of named plaintiffs was

held May 13th and 14th. On May 30, 1975, plaintiffs filed a

Renewal Of Motions To Reconsider Order Denying Class Actions And 6

8

6 /

The subpoenaed documents include, inter alia,

personnel folders and race of applicants to GS-5 and GS-7 posi

tions since 1960; personnel folders and race of persons who

received a supervisor's appraisal or performance rating from two

members of the promotion panel involved in named plaintiffs'

individual claim; notes, forms, rating sheets, or other memoranda

from GS-5 or GS-7 rating panels since 1960; GS-5 and GS-7 registers

with racial identification since 1960, announcements for each

GS-5 and GS-7 position since 1960; documents identifying and

describing any person who served on any GS-5 or GS-7 rating and

selection panel since 1960; and documents describing application,

cosideration and selection information and statistics for each

GS-5 and GS-7 promotion register since 1960.

9

To Compel Defendants To Answer Interrogatories In Light Of

Evidence Presented At The Trial Of The Individual Claims (App.

92b;.) . The district court then issued its final judgment of

July 24, 1975 against named plaintiffs on their individual

claims of discrimination (App. 100).

Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal on September 17,

1975 (App. 122). This court has jurisdiction pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1291 to review denial of class action consideration

of this Title VII suit challenging across-the-board employment

discrimination at the Naval Air Rework Facility in Norfolk,

Virginia; denial of discovery of broad and systemic patterns

of discrimination to properly prepare for trial of the

individual claims of the named plaintiffs; and denial of the

individual claims.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Historic Racial

Discrimination At NARF

Although plaintiffs were specifically precluded from

conducting discovery and presenting evidence of historic racial

discrimination at NARF at the trial of the individual claims,

the reco.rd does contain some such evidence.

1. Trial Testimony Concerning

Job Histories Of Black Employees

The job histories of black employees that do appear

in the record illustrate how historic discrimination adversely

affected their employment rights. Plaintiff Ferebee was

initially employed at NARF in the 50000 department in menial

WG helper or labor position in 1947 when such positions were

still all-black. The situation was the same when plaintiff

Day began his employment in 1961. (App. 79, 324-25)-

The work done by helpers and laborers in the 50000 department

is cleaning aircraft; i_.e. , removing paint, corrosion, rust,

dust, dirt, grime and grease and particles from aircraft and

components with solvents that give off toxic fumes (App. 324,

364 ). These positions remain traditional black jobs. Thus,

as late as 1971, all 34 helper or laborer and 108 of 166 inter

mediate positions in the 50000 department were held by black

employees. The NARF NORVA Representation table for 1972 shows

the comparable statistics were 30 of 34 helpers or laborers and

147 of 194 intermediates. The statistics for low level WG

positions for 1973 and 1974 are similar (DX 11, App. 627, 630).

contrast, black employees held only 26 of 42 journeyman or

equivalent positions in 1971 and 6 of 17 in 1972 (id.).

Plaintiff Ferebee in 1957 and plaintiff Day in 1965

each advanced to the WG position of production dispatcher in

the 50000 department which was the top job in the line in terms

of pay, working conditions and responsibilities open to those

who start as helpers and laborers (App. 325-26). (Plaintiff

Holloman began his NARF employment in 1956 as a warehouseman

and advanced, apparently through a different progression, to

_JZ/Prior to 1961, the installation was known as Naval

Supply Center. In 1961, the former employees of the Center

became a part of the newly created NARF.

11

production dispatcher in the 50000 department in 1961.) The

dispatcher position was a dead end job without further advance

ment possibilities (App. 189-90, 325-326, 365), although the

production dispatcher's duties are similar to those of the pro

duction controller's position (App. 325). The

controller position prior to 1968 was restricted to employees

with journeyman or trade background (App. 329 , 305).

In 1968 the position was changed from ungraded to GS but the

qualifying experience still limited candidates to.those with

journeyman or trade background (App. 318-19). Black employees

8_/naturally had difficulty obtaining such experience. Paper

qualifications and testing scores were bars to transfer and

promotions (App. 331, Tr. 228). Named plaintiffs did not receive

details or temporary promotions to production controller until

19 71.

It was not until 1972 that entry qualifications for

the production controller position were changed in order to

permit black employees, including named plaintiffs, to promote

to the intitial 50000 department production controller GS-5

position ( DX 20, App. 102 ). Thus, the 1973 Affirmative

Action Plan characterized as a problem that the-entry level of

8/

For example, plaintiff Day, after becoming a pro

duction dispatcher, tried unsuccessfully to get a demotion in

order to be able to gain journeyman experience to qualify for

production controller (App. 329 ). Plaintiff Ferebee applied

unsuccessfully for a transfer for the same purpose (App. 365 ).

Even when black employees had a journeyman background1", as did

plaintiff Simmons, they were usually passed over for the position (App. 436 ) .

12

production controller GS-5 and GS-7 positions eliminated many

applicants with potential (DX 13, App. 674 ). The 1974 Plan

took note of the problem that women and minorities are

underrepresented in grades GS-9 through GS-13 and specifically

required the 50000 department to increase the number of minori

ties in grade GS-9 by 200% (DX 13, App. 703-4). DX 11 statis

tics show that for 1971 through 1973 when the formal administra

tive complaint in the instant case was filed, there was only

one black GS-9 production controller in the 50000 department and

none in the higher GS grades. In 1971 there were 41 white

employees at GS-9 and 28 at higher GS levels. In 1973, there

were 38 at GS-9 and 31 at higher GS levels. The comparable

9/statistics for 1974 are 39 and 37 (App. 632).

The present record indicates that the almost all

white supervisory force, supra, affects promotional rights of

black employees in such ways as detailing and temporary pro

motions (see, e. g., App. 331-33, Tr. 399-402) , .transfers , assignment to

duties generally, supervisory appraisals (see, e.g., App. 338-

339 ) and promotion panels. As noted above, DX 13 indicates

that supervisory enforcement of EEO goals was a persistent

problem. Defendants' trial witnesses also indicated that supervi

sors' subjective "judgment" is a sanctioned and significant

9/

DX 11 statistics also indicate that although the

50000 department is disproportionately black because of the

large number of low level ungraded black employees, white

employees predominate at all high level and supervisory

positions graded or ungraded (App. 620).

13

factor in most employment decisions at NARF, with respect

10/to the individual claim, infra-

2 - NARF EEO Affirmative Action Plans

The Affirmative Action Plans acknowledge problems in

the NARF equal employment opportunity program and specify

what corrective actions are required to achieve "full integration

in all occupations and levels". The' same problems with, inter

alia, recruitment, utilization of skills of present employees,

upward mobility and treatment by supervisors recur in all the

11/ plans.

Patterns and Policies of Employment Discrimination

Plaintiffs were also precluded from conducting

discovery and presenting statistical evidence of patterns and

policies of present-day systemic discrimination, but some NARF-

wide statistics are set forth in several of defendants’ exhibits

(DX 11, App. 620). Although these statistics are unrefined,

10/

Although plaintiffs were limited to discovery and

presentation of evidence concerning the specific individual

claims, plaintiffs' witness James testified to several instances

of discrimination resulting from actions by white NARF supervi

sors in another department and Executive Officer Commander

Zaborniak. (App. 407-22). This testimony was uncontradicted.

11/

The following were problems in 1973: "Minority

Group Members And Women Are Not Adequately Represented In College

Recruitment Hires"; "The Entry Level Of Some Positions Eliminate

Many Applicants With Potential"; "Some Employees In Lower Level

Dead End Positions Have Secondary Skills Which Qualify Them For

Occupations With Advancement Patterns"; "In Many Cases Represen

tation of Minorities And Women Within Selection Range Is Below

That Of Their Representation In Qualifying Occupations"; Under

Present Structure Of Supervisory Training Courses, The Importance

Of EEO^As An Item Of Special Emphasis Not Realized To Desired

Extent ; and No Criteria Have Been Established To Effectively

(Footnote 11 continued on page 14 )

14

the gross disparities are evidence that present practices

perpetuate past discrimination.

12/

1* 1971 and 1972

While 17% of all NARF Employees in 1971 held GS

positions (863 of 5085) and 20% of all white employees (795 of

3894), only 6% of all black NARF employees held GS jobs (68 of

1191). Similarly, while 23% of all NARF employees were black

(1191 of 5085) and 27% of all non-GS employees were black (1123

of 4222), only 8% of all NARF GS employees were black (68 of

13/

863) . In 1971, 49% of black non-GS employees (553 of 1123)

(Footnote 11 continued from page 13 )

Measure Supervisor Performance In Support Of EEO." The 1974

Plan contains the following additional problems: "Women And

Minorities Are Underrepresented In Grades GS-9 Through GS-13";

"Some Problems Do Not Have Normal Progression Route To The

Next Higher Level"; "Some Employees Desire To Change Their

Career Field To One Which Provides Better Or More Interesting

Work Opportunities"; "Serious And Significant Inconsistencies

Exist Among Panels Established To Evaluate Job Applicants".

The lists of problems in the 1971, 1972 and 1975 plans are

similar (ox 11, App. 620).

12/

For 1971 and 1972, DX 11 contains tables showing (a)

number and percent of black and total General Schedule or GS

employees by department and GS level, and (b) number and percent

of black and total non-GS or ungraded employees by department and

job title. The 1971 tables appear complete, but GS and non-GS

statistics were not available for the large 60000 department and

non-GS statistics for the small 90000 department in the 1972

tables. These tables generally demonstrate a consistent pattern

of disproportionate concentration of black employees at lower job

levels (id.).

11/It should be noted that non-GS employees include

the sub-journeyman positions of helper (including laborer) and

intermediate in which black employees predominate and super

journeyman supervisory positions in which black employees are

largely absent; the substantial bulk of the non-GS category,

however, are journeyman, intermediate and helper positions.

15

were in the helper (including laborer) category which was 65%

black (182 of 281) and the intermediate category which was 63%

black (371 of 594) compared to 21% of total non-GS employees

(875 of 4222) and 10% of white non-GS employees (322 of 3099) .

Fully 66% of total non-GS employees (2782 of 4222) and 72% of ■

white non-GS employees (2242 of 3099) occupied journeyman or

equivalent positions compared to 48% of black non-GS employees

, 14/(540 of 1123). Of 562 superjourneyman non-GS employees, 95%

were white (533.of 562) and 5% black (29 of 562). Superjourney

man positions in which there were no Blacks include, inter alia,

General Foreman II, Superintendent I, Superintendent II, instructor

, u ■ . 15/and progressman. This pattern was consistent across departments.

As to GS positions in 1971, 46% of black GS employees

(31 of 68) were in grades below GS-6 compared to 21% of total

GS employees (182 of 863) and 19% of white GS employees (149 of

795). 43% of black GS employees (29 of 68) were in grades GS-6

through GS-10 compared to 55% of total GS employees (471 of 863)

and 56% of white GS employees (442 of 795). 9% of black

14/

The worker trainee position that appears on the

tables is assumed not be a superjourneyman position.

15/

In addition., while 27% of non-GS employees were

black, over half were concentrated in three departments: the

50000 department (42% or 172 of 407), the 60000 department (40%

black or 156 of 394), and the 92000 department (41% black or

272 of 666) ; only 28% of white non-GS employees were in these

departments. The four other sizeable departments were the

94000 department (17% black or 176 of 1027), the 95000 depart

ment (16% black or 82 of 509), the 96000 department (23% black

or 147 of 633) and the 97000 department (20% black or 113 of

574); 72 % of white non-GS employees were in these departments

(2235 of 3099). The 10000 department (5 employees), 20000

department (1 employee) and 9000 department (6 employees), have

small numbers of non-GS positions.

17

and 1972. The breakdown of employee distribution by race xn non-

17/

GS positions is also comparable.

As to GS positions in 1973, 52% of black GS employees

(41 of 79) were in grades below GS-6 compared to 27% of total

GS employees (244 of 916) and 24% of white GS employees (203

of 837). 38% of black GS employees (30 of 79) were in grades

GS-6 through GS-10 compared to 47% of total GS employees (433 of

916) and 48% of white GS employees (403 of 837). 10% of black

GS employees (8 of 79) were in grades higher than GS-10 compared

to 26% of total GS employees (240 of 916) and 28% of white GS

employees (232 of 837). This pattern was consistent from

department to department -

17 /— Almost all or 96% of black non-GS employees held

Regular Nonsupervisory or WG positions (861 of 903) rather than

Regular Supervisory or Production Raciiitatxng; the proportion

of WG employees to total non-GS employees was 86% (3040 of 3528)

and of white WG employees to white non-GS employees 63* (2179

3462.) Although 28% of WG were black (861 of 3040), black

employees were disproportionate concentrated in lower levels.

Thus, 7% of black WG employees were in grades lower than WG-6

(62 of 861) compared to 5% of total WG employees (139 of 3040)

and 4% of white WG employees (77 of 2179). 84o of black WG

employees were in grades WG-6 through WG-11 (720 of 861) compared

to 76% of total WG employees (2316 of 3040) and 74* of white

emolovees (1596 of 2179). 9% of black WG employees were in grades

higher than WG-11 (79 of 861) compared to 19% of total WG employees

(585 of 3040) and 23% of white WG employees (506 of 2179) . Witn

respect to Regular Supervisory or WS employees, 12% 'were ^lack

(26 of 216) and black employees were disproportionately_clustered

at lower levels. Thus, 38% of black WS employees were m grades

below WS-7 (10 of 26) compared to 6% of total WS employees (12

216) and 1% of white WS employees (2 of 190). 58% of black

employees were In grades wl-7 through WS-11 (15 of 26) compared

toP81% of total WS employees (174 of 216) and 84* of white WS

emolovees (159 of 190). Only 6% of Production Facilitating

or WD, WN, WB, WX and WY positions were held by black employees

(16 of 272).

17

and 1972. The breakdown of employee distribution by race in non-

17/GS positions is also comparable.

17/

Almost all or 96% of black non-GS employees held

Regular Nonsupervisory or WG positions (861 of 903) rather than

Regular Supervisory or Production Facilitating; the proportion

of WG employees to total non-GS employees was 86% (3040 of 3528)

and of white WG employees to white non-GS employees 63% (2179 of

3462) . Although 28% of WG were black (861 of 3040) , black

employees were disproportionate concentrated in lower levels.

Thus, 7% of black WG employees were in grades lower than WG-6

(62 of 861) compared to 5% of total WG employees (139 of 3040)

(77 of 2179). 84% of black WG

through WG-11 (720 of 861) compared

(2316 of 3040) and 74% of white WG

of black WG employees were in grades

,qnr , ̂ -7* compared to 19% of total WG employees(585 of 3040) and 23-s of white WG employees (506 of 2179) . With

respect to Regular Supervisory or WS employees, 12% were black

(26 of 216) and black employees were disproportionately clustered

at lower levels. Thus, 38% of black WS employees were in grades

below WS-7 (10 of 26) compared to 6% of total WS employees (12 of

216) and 1% of white WS employees (2 of 190). 58% of black WS

employees were m grades WS-7 through WS-11 (15 of 26) compared

to 81-3 of total WS employees (174 of 216) and 84% of . white WS

employees (159 of 190). Only 6% of Production Facilitating

U 6 Wof 272)WB' WX ^ m p°sitions were held bY black employees

and 4% of white WG employees

employees were in grades WG-6

to 76% of total WG employees

employees (1596 of 2179). 9%

higher than WG-11 (79 of 861)

18

Claims Of The Named Plaintiffs

The favored positions in the 50000 department are

the positions of production controller GS-9 and above (App. 331).

Since 1968, the production controller position has been a GS

position and subject to the merit promotion policies set forth

in General Schedules Handbook X-118 (DX 9, App.189-90, 331). In

addition to the production controller positions at the GS-9

level and above, there are such positions at GS-5 and GS-7.

Because of the nature of federal employment promotion procedures

(App. 9 9 7-10 2 0), the positionof production controller GS-7 is

generally considered as the threshold position for the GS-9 and

higher levels in the 50000 department (App. 331).

On July 20 and July 27, 1972, respectively, Merit

Promotion Vacancy Announcements No. NG14A-72, for the position

of Production Controller GS-7, and No. NG13A-72 for the position

of Production Controller GS-5 were published (App. 79-80) . The

requirements for the GS-5 and GS-7 positions as described in the

two announcements were virtually identical (App. 81 ). In

particular, the duties of the production controller and the

evaluation factors for both announcements were identical (App.

540). The announcements differed only in the qualification

standards as prescribed by Handbook X-118 regarding length of

general and specialized experience required for any GS-5

and GS-7 production controller series position. Because of the

similarity in requirements, several applicants, including the

four plaintiffs, submitted identical applications for both

positions (App. 80 ).

The GS-5 rating panel met in the fall of 1972 (App.

80 ). The panel met for some weeks and used the information

contained in the applications and the official personnel folders

in its deliberations (App. 80 ). The panel used the GS-5

Production Control crediting plan in rating the

eligible applicants (App. 80 ).

The GS-7 panel met during the summer of 1973 after

the GS-5 register had been established and promotions made to

18_/

GS-5 positions (App. 80 ). The GS-7 panel used the crediting

plan for Production Controller GS-7 and did not have access to

the personnel folders (App. 80 ).

On August 15, 1973, notices of ratings for the

Production Controller GS-7 were mailed to the applicants. On

September 19, 1973, a revised register for said position was

19/

announced (App. 600 ). As a result of the revised GS-7 register

plaintiffs became aware of certain discrepancies between the

rankings of applicants on the GS-5 and GS-7 registers.

Specifically, plaintiffs noticed that several Whites who had

applied for both registers ranked lower than Blacks on the

GS-5 .register, but higher than those same Blacks on the GS-7

19

lfi/The GS-5 panel's actions had no effect on the GS-7

panel's deliberations since the applications could not be up

dated (App. 1004). Compare the lower court's finding at p. loo-

101 of the Appendix.

19/

The revised register is a ranking of each applicant

made up after all applicants are given an opportunity to informal

ly challenge their original rating ( Tr. 230-31) .

20

register (App. 82 )• Plaintiffs' rankings, as well as the

rankings of other Blacks were so much lower on the GS-7 register

that they were placed out of the area of consideration for

2_0_ /

promotion (App. 82 ) .

A comparison of the rankings on the two registers is

presented in PXlA - 1G (App. 559-66). That comparison shows that

of all applicants who applied for both registers, 40.8% of the

white applicants were ranked higher on the GS-7 register than

they had been on the GS-5 register. By contrast, 77.1% of all

Blacks who applied for both registers ranked lower on the GS-7

register than they had on the GS-5 register (id.). Consequently,

Whites who had been deemed less qualified than Blacks to hold

GS-5 positions were now being placed in GS-7 positions ahead of

2_1_/

those same Blacks.

As a result of these disparities, plaintiffs contacted

Luther Santiful, Deputy Equal Employment Opportunity Officer

(DEEO), and informed him that they believed they had been

discriminated against because of race (App. 82 ). Mr. Santiful

referred them to EEO Counselor H. R. Nelson for the purpose of

filing an informal complaint of racial discrimination in

accordance with CSC regulations (App. 82 ). On November 26,

2_0_/

Plaintiffs had previously been promoted from the

GS-5 register (App.1021).

21_/

It should be noted that only 14.3% of all Blacks

who applied for both registers were ranked higher on the GS-7

register than they had been on the GS-5 register.

1973, Mr. Nelson submitted a written report on plaintiffs'

allegations to Commander Walter J. Zaborniak, Executive Officer

of NARF (App.263-264).Thereafter, a meeting was held between

the plaintiffs and Mr. Santiful at which plaintiffs were

requested to return their copies of Nelson's report because

of "libellous" statements contained therein (App.381-383). The

libellous statements were Nelson's findings that certain panel

22/members had discriminated against plaintiffs (App.265 ). As

a result, Nelson's report was retyped, redated and submitted to

Captain Shine on November 28, 1973. The revised report indicated

that "[t]he ratings performed by the GS-7 rating panel have the

appearance of being racially biased." (App. 82) .

At some time between November 26 and 29, 1973, and

with Captain Shine's knowledge and consent, a special committee

was set up by Commander Zaborniak to explore the cause of the

disparities between the GS-5 and GS-7 rankings (App. 82 ). This

action was entirely outside the EEO complaint process (App. 82 ),

23/

and was unprecented (App. 269-70) . The special review committee

consisted of four persons, selected and briefed by Commander

Zaborniak (App. 270 ). Using the same crediting plan utilized

by the GS-7 panel, the review committee rated each of the top 30

applicants on the GS-7 register. Commander Zaborniak, with the

21

22_ /

Compare Captain Shine's testimony that "there are no

restrictions on what a counselor can put in his investigation

report." App. 150

23/

In fact, plaintiffs specifically objected to the

establishment of such a committee (App. 573 ).

assistance of personnel specialists, then applied the same

procedures to rank the applicants as did the GS-7 panel

(App. 269 )• The results of this review are located at p. 772

of the Appendix. Those results reveal a disparity between

the rankings of the GS-7 panel and those of the review

committee. In general, Whites were ranked lower by the

review committee than by the GS-7 panel. By the same token,

Blacks were ranked higher by the review committee than by

the GS-7 panel (id.). Basically, the review committee

results were much more in line with the rankings as they had

appeared on the GS-5 register.

On or about December 3, 1973, Zaborniak and Santiful

24/

again met with the plaintiffs. In spite of the discrepancies

found by his committee, Zaborniak informed plaintiffs that they

"all came out about the same." Tr. 345-346. Plaintiffs requested

to see the committee's results, but Zaborniak refused ( Tr.346).

Because no action was taken on their informal

complaint, plaintiffs filed a formal charge of racial discrimination

on December 3, 1973 (App. 83 ). In addition to their allegation

that they had been placed out of the area of consideration for

promotion to GS-7 because of race, plaintiffs also alleged that

the discrimination complained of occurred "when there is a majority

of Black applicants." App.£3, 735. Pursuant to applicable CSC

22

2 4/

Plaintiffs' requests to meet with Captain Shine

were refused by Zaborniak on the basis that Captain Shine could

not jeopardize his ability to eventually make an unbiased

decision (App. 134 ). However, Zaborniak made frequent reports

to Shine concerning his (Zaborniak's) findings (App. 278 )•

and agency regulations, Moses T. Boykins was assigned to

investigate plaintiffs' formal complaint. Said investigation

was conducted from December 21, 1973 to February 15, 1974

(App. 84). As a result of his investigation, Mr. Boykins

found that plaintiffs were discriminated against because of

their race and recommended that corrective action be taken

(App. 84 ). Mr. Boykins' finding marked the first time at

NARF that any investigator had made a finding of racial

25/

discrimination (App. 188 ). In spite of this finding,

however, Captain Shine determined that a second investigation

was necessary. This also marked the first time that an

investigator's report was rejected or that a second investigation

was ordered (App. 84 ). In requesting a second investigation,

Captain Shine stated that Mr. Boykins' investigation was not

sufficient to allow him (Shine) to reach any determination on

plaintiffs' complaint (App. 84 ).

The second investigator, Berton E. Owens, conducted

the further investigation requested by Captain Shine from

26/

March 14 through March 29, 1974. As a result of his investiga

tion, Mr. Owens concluded that although the GS-7 panel had used

invalid procedures, he could not make a finding of racial

discrimination (App. 764). Although Captain Shine testified

23

25/Prior to this time, approximately 15 formal

complaints of racial discrimination had been filed at NARF

(App.187-188).

26/This further investigation consisted of Mr. Owens'

obtaining additional affidavits from panel members and other

alleged discriminators (App. 764 and 180-8]) •

that Owens' report was also insufficient (App. 182 ), he

decided to accept the findings contained therein because "at

some point in time I had to come to some proposed disposition

in this case." App. ]_86 • As a result of that disposition,

plaintiffs filed the instant lawsuit.

A R G U M E N T

Introduction

The questions presented for review in this action

against a federal agency are not unprecedented in employment

discrimination jurisprudence. Whether class action enforcement

of equal employment opportunity is appropriate has been decided

uniformly in favor of employees' full access to the judicial

process. See, e.g., Moss v. Lane Company, Inc., 4 71 F.2d

853 (4th Cir. 1973). Similarly, the right of individual

plaintiffs to conduct discovery of systemic plant-wide discrimi

nation, see, e.g., Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333

(10th Cir. 1975), and the decisive importance of statistical

evidence in the determination of discrimination, see, e.cj. ,

Barnett v. W. T. Grant Company, 518 F.2d 543 (4th Cir. 1975), have

repeatedly been affirmed. Simply stated, federal employees

seek no more or less than what employees of a private company,

see, e.g., Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d

1377 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972), or

state or local government employer, see, e.g., Morrow v.

Crisler, 479 F.2d 960(5th Cir. 1973), affld en banc, 491 F .2d

1053 (5th Cir. 1974) , are entitled. The federal government, on

the other hand, seeks an exemption from the kind of challenge

24

25

to discriminatory policies and practices it has consistently

encouraged in this and other courts against all other alleged

discriminatory employers. See, e_. g. , United States v. Chesapeake

and Ohio Ry Co., 471 F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972); Graniteville

Co. v. EEOC> 438 F.2d 32 (4th Cir. 1971).

These issues are but three of the narrow and techni

cal devices which government lawyers defending federal agencies

in employment discrimination suits have raised in a concerted

effort to forestall the full judicial consideration of the

merits required in Title VII litigation. Other such devices

include (a) denying federal employees' right to bring a Title

VII action for discimination occurring prior to the effective

2 7/

date of the statute; (b) denying the powers of the federal

2 8/

courts to grant preliminary injunctive relief under Title VII;

(c) denying federal employees 1 right under Title VII to a

plenary trial or trial de novo in favor of a review of the

29/

administrative record only; (d) seeking remand to agency

3 0/

proceedings to complete an administrative record; and

— See, e.g., Roger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir.

1974) . The Solicitor General recently conceded error on this

issue in his Memorandum In Response to Petition for Rehearing in

Place v. Weinberger, October Term, 1974, No. 74-116, petition

for rehearing pending.

2—^See, e.g, Parks v. Dunlap, 517 F.2d 785 (5th Cir.

1975) .

^See, e.g., Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108 (D.C.

Cir. 1975) .

3 0/

See, e.g., Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir.

1975) .

26

(e) denying the existence of alternative bases of jurisdiction

31/

for judicial enforcement. The instant case is an example of

the comprehensive nature of the government's defense strategy:

the government also advanced the last three of these positions

below. If the district court had accepted all of the govern

ment s contentions, it would have been reduced to a rubber stamp

for the review of an administrative record compiled by agents

of the defendant agency concerning what happened to individual

employees. The district court did order a trial de novo of the

individual claims under Title VII, but without class action,

full right to discovery or determination under applicable Title

VII substantive law. Thus, no broad inquiry was conducted into

challenged employment policies and practices whose adverse dis

parate impact on black employees is evident even on the record

compiled, notwithstanding the "plain . . . purpose of Congress

to assure equality of employment opportunities and to eliminate

those practices and devices which have fostered racially

stratified job environments to the disadvantage of minority

citizens." McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800

(1973), citing Griggs v. Duke power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429 (1971).

See also Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, ____U.S. , 45 L.Ed 2d

280, 296 (1975). ,

Although analytically related because of the

significance of scrutiny of systemic discrimination throughout,

the questions presented nevertheless require independent

31/

See, e.g., Petterway v. Veterans Administration

Hospital, 495 F.2d 1223 (5th Cir. 1975).

27consideration and resolution. First, the lower court

32_/

erroneously precluded a class action. Second, denying

plaintiffs the right to prepare for trial of the individual

claims by conducting broad discovery is in itself sufficient

reason to reverse the ruling on the individual claims.

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra. Third, the decision

on the individual claims is clearly erroneous because of the

failure to apply recognized substantive Title VII law on

statistical demonstration of the prima facie case and rebuttal

evidence to the adjudication of the claims. Had the district

court done so, plaintiffs as a matter of law would have pre

vailed even on the existing record. For this reason, the

decision on the individual claims should be reversed and

judgment in favor of named plaintiffs ordered. Barnett v. W.

T . Grant Co., supra.

I

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING

FEDERAL EMPLOYEES THE RIGHT TO MAIN

TAIN A CLASS ACTION PURSUANT TO RULE

23(b)(2) FED. R. CIV. PRO. ON BEHALF

OF OTHER SIMILARLY SITUATED EMPLOYEES

The lower court concluded that a class action could

not be maintained for claims arising under §717 of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-16

for lack of exhaustion of available administrative remedies.

The named plaintiffs filed their joint "individual" administra

tive complaint from the failure to promote under 5 CFR §§713.211

The law of this circuit is clear that the action can

so proceed irrespective of any questions concerning the

individual claims. Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co,

supra, at 1380; Moss v. Lane Company, Inc, supra; Barnett v. W.

T. Grant Co., supra, at 548 n.. 5.

33/ 28

et seq., but did not file a "third party complaint" pursuant

34/

to 5 CFR §713.251 The district court's order of January 20,

1975 states:

"From the allegations of the complaint

it is very unlikely that the bases of

failing to promote or advance plaintiffs

would govern others. Further, they are

limited in this case to raising those

issues presented in their administra

tive proceedings because they will not

have exhausted administrative remedies

as to other issues." App. 65-55.

Although the lower court did not specifically refer to

exhaustion of third party complaint procedures, defendants'

reliance and express citation of §713.251 erases any doubt as

to the lower court's reasoning, supra, p. 5 . Moreover, the

lower court made clear that its ruling on exhaustion of class

wide claims was the only reason a class action could not be

maintained (App. 63 - 65)..

This result erroneously celebrates form over substance

The duty of the Civil Service Commission and federal agencies

to consider systemic, classwide discrimination in the complaint

resolution process as well as other equal employment oppor

tunity programs derives from statutory command, not from the

trigger of specific allegations. §2000a-16(a) states "All

personnel actions affecting employees or applicants for employ

ment . . . shall be made free from any discrimination based on

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." (Emphasis

33/

5 CFR §713.211 et_ seq. is set forth in Attachment A

5 CFR §713.251 is also set forth in Attachment A.34/

29

added). The Senate committee report explained the meaning of

this provision when it expressly called into question the

assummption of the Civil Service Commission that "employment

discrimination in the Federal Government is solely a matter of

malicious intent on the part of individuals."

"Another task for the Civil Service

Commission is to develop more expertise

in recognizing and isolating the various

forms of discrimination which exist in

the system it administers. The Commission

should be especially careful to ensure

that its directives issued to Federal

agencies address themselves to the various

forms of systemic discrimination in the

system. The Commission should not assume

that employment discrimination in the

Federal Government is solely a matter of

malicious intent on the part of individuals.

It apparently has not fully recognized that

the general rules and procedures that it has

promulgated may in themselves constitute

systemic barriers to minorities and women.

Civil Service selection and promotion

techniques and requirements are replete

with artificial requirements that place

a premium on 'paper' credentials. Similar

requirements in the private sectors of

business have often proven of questionable

value in predicting job performance and

have often resulted in perpetuating existing

patterns of discrimination (see, e.g.,

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., . . . Tne inevitable

consequence of this kind of technique in Federal

employment as it has been in the private sector,

is that classes of persons who are socio-economically

or educationally disadvantaged suffer a very

heavy burden in trying to meet such artificial

qualifications." 35/

The House Committee concurred:

"Aside from the inherent structural

defects the Civil Service Commission has

been plagued by a general lack of

_iy

Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate Comm, on Labor and

Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 (Comm. Print 1971) (hereinafter

"Legislative History") at 423.

30

expertise in recognizing and isolating

the various forms of discrimination which

exist in the system. The revised directives

to Federal agencies which the Civil Service

Commission has issued are inadequate to meet

the challenge of eliminating systemic dis

crimination. The Civil Service Commission

seems to assume that employment discrimination

is primarily a problem of malicious intent on

the part of individuals. It apparently has not

recognized that the general rules and procedures

it has promulgated may actually operate to the

disadvantage of minorities and women in systemic

fashion." Legislative History at 84.

There is, in short, no need for extrinsic notice to the agency

of the possibility of classwide discrimination. Whether an

employee makes allegations of systemic, classwide discrimination

in any administrative complaint, a fortiori, is unnecessary to

initiate the agency's statutory obligation to scrutinize every

3jj/

case and search for indications of systemic discrimination.

What is at issue is not exhaustion of administrative

remedies per se, but the whole technical requirement of specific

classwide allegations made in the course of administrative

exhaustion. The scope of exhaustion required in this and other

circuits with respect to private employee class actions is no

different than if they brought a Title VII action on their own

behalf only; it has been recognized that a single charge of

racial discrimination is sufficient notice for employer self

correction and a predicate for class action treatment. See

infra, p. 45 . The rule should be the same for federal employ

ment so that any complaint, whether denominated individual or

third-party, should be sufficient exhaustion for a class action

suit.

— ^It should also be clear that the very notion of

different administrative procedures for individuals and class

complaints is itself suspect. See pp. 40-44/ infra.

The D. C. Circuit in Hackley v. Roudebush, supra,

31

at 152-53 n. 177, has so ruled. The specific question that

Judge Wright addressed was whether resolution of the trial

de novo issue affected federal employees1 rights to bring class

actions. The court considered the strong federal policy of

encouraging class action litigation in situations of pervasive

discrimination (see infra, p. 34 ), 1972 Title VII legislative

history affirming the importance of class actions in employment

discrimination litigation,(see infra, p.44 ), and private

sector case law (see infra ppv32-33>, anĉ concluded by citing

the Congressional injunction to require scrutiny of systemic

discrimination:

" . . . [E]ven if the District Courts

were limited to review of the administra

tive record, it would appear that class

action treatment after a single individual

had exhausted his administrative remedies

would be proper; as Senator Williams had

argued, discrimination--particularly when

it is systemic— is almost inherently

appropriate for class treatment, and the

CSC's regulations in effect require that

agencies treat each individual's complaint

broadly enough to encompass discrimination

that may be practiced against others

similarly situated:

'The [agency] investigation shall

include a thorough review of the

circumstances under which the

alleged discrimination occurred,

the treatment of members of

the complainant's group identi

fied by his complaint as com

pared with the treatment of other

employees in the organizational

segment in which the alleged

discrimination occurred, and any

policies and practices related

to the work situation which may

constitute, or appear to con

stitute, discrimination even

32though they have not been expressly

cited by the complainant.'"

5 CFR §713.216(a) (1974) .

Applying Hackley , Judge Richey in Barrett v. U. S_. Civil

Service Commission, C.A. No. 74-1694 (D.D.C., decided

December 10, 1975), certified a federal employment class action

over defendant agency's claim that third party procedures were

not resorted to, and granted plaintiffs' motion for declaratory

judgment that "consistent with their responsibilities under 42

U.S.C. §2000e et seq. defendants must accept, process, and

resolve complaints of class and systemic discrimination which

are advanced through individual complaints of discrimination

and must provide relief to the class when warranted by the

37/

particular circumstances of each case." Compare Keeler v.

Hills, N.D. Ga. C. A. C74-2152A, 2309A, (decided

November 12, 1975); Ellis v. NARF, 10 EPD 1110,422 (N.D. Cal. 1975).

Appellants merely urge the rule in private Title

VII litigation that "the 'scope' of the judicial complaint

is limited to the 'scope' of the EEOC investigation which can

reasonably be expected to grow out of the charge of

discrimination:" Sanchez v. Standard Brands, Inc., 431 F.2d

455, 466 (5th Cir. 1970). There is no doubt that an EEOC

37/

Lest there be any doubt, it was further ordered

"that defendant Civil Service Commission shall modify existing

regulations and/or draft new regulations which reflect its

above-declared responsibilities."

33

investigation is classwide. Congress did more than find the

Civil Service Commission inexpert in recognizing and isolating

discrimination, supra; it went on to direct the Commission to

•learn from the EEOC's expertise in dealing with discriminatioi

The district court's decision approving this class

action bar is clearly in error. First, Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ.

Pro., and the face of §2000e-16 indicate that only the

exhaustion of individual administrative remedies is necessary

for judicial consideration of class action treatment in the

instant case. Second, Congress expressly disclaimed any desire

to erect any exhaustion bars to Title VII class actions in

40/

1972.

38/

39/

38/Graniteville Co v. EEOC, 438 F.2d 32 (4th Cir. 1971);

Georgia Power Co. v. EEOC, 412 F.2d 4.62 (5th Cir. 1969); Blue

Bell Boots Inc. v. EEOC, 418 F.2d 355 (6th Cir. 1969); Local No.

104, Sheet Metal Workers Int'1 Assoc. v. EEOC, 439 F.2d 237

(9th Cir. 1971); Motorola, Inc. v. McClain, 484 F.2d 1139 (7th

Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 936 (1974); EEOC v.

University of New Mexico, 504 F.2d 1296 (10th Cir. 1974); New

Orleans Public Service, Inc. v. Brown, 507 F .2d 160 (5th Cir.

1975) .

12/

"The Committee wishes to emphasize the significant

reservoir of expertise developed by the EEOC with respect to

dealing with problems of discrimination. Accordingly, the

committee strongly urges the Civil Service Commission to take *

advantage of this knowledge and experience and to work closely

with EEOC in the development and maintenance of its equal

employment opportunity programs. Legislative History at 425.

See also Legislative History at 414.

A n /For the same reasons, Rule 23 class actions under

the Fifth Amendment, 5 U.S.C. §§7151, 7154 and Executive Order

11478 brought pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1331(a), 1343(a), 1361,

1364(a)(2), 2201 and 2202 and 5 U.S.C. §5596 are not precluded.

See, e.g. , Davis v. Washington, 512 F.2d 956 (D.C. Cir. 1975);

Petteway v. V.A. Hospital, 495 F.2d 1223 (5th Cir. 1974).

34

A. Class Actions Provided For In The

Federal Rules Of Civil Procedure

Are Not Precluded Or Limited In Any

Way By The Statutory Language Of

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16________________

The right of federal employees to bring class actions

to enforce §2000e-16 guarantees of equal employment opportunity

derives in the first instance from Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro.,

in accordance with 28 U.S.C. §§2072, 2073. Sibbach v. Wilson

&_ Co., 312 U.S. 1 (1941) . The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

with certain exceptions not here relevant, extend to "all suits

of a civil nature whether cognizable as cases at law or in equity

or in admiralty." The federal courts thus have no discretion

to make ad hoc determinations whether specific civil action

statutes permit class action enforcement; class actions are

permitted unless statutory language expressly precludes or limits

class action treatment. Section 2000e-16, by its terms, permits

judicial consideration of class actions without the exhaustion

imposed by the district court.

1. Rule 23(b)(2) Fed. R. Civ. Proc.

Nothing in Rule 23(b)(2) itself requires the district

court's exhaustion bar. The inquiry required by Rule 23(b)(2)