Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier

Working File

August 4, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Memorandum from Gibbs to Guinier, 1984. 92d90249-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ac81b1a2-8302-4388-b78f-fe77455f8c55/memorandum-from-gibbs-to-guinier. Accessed February 09, 2026.

Copied!

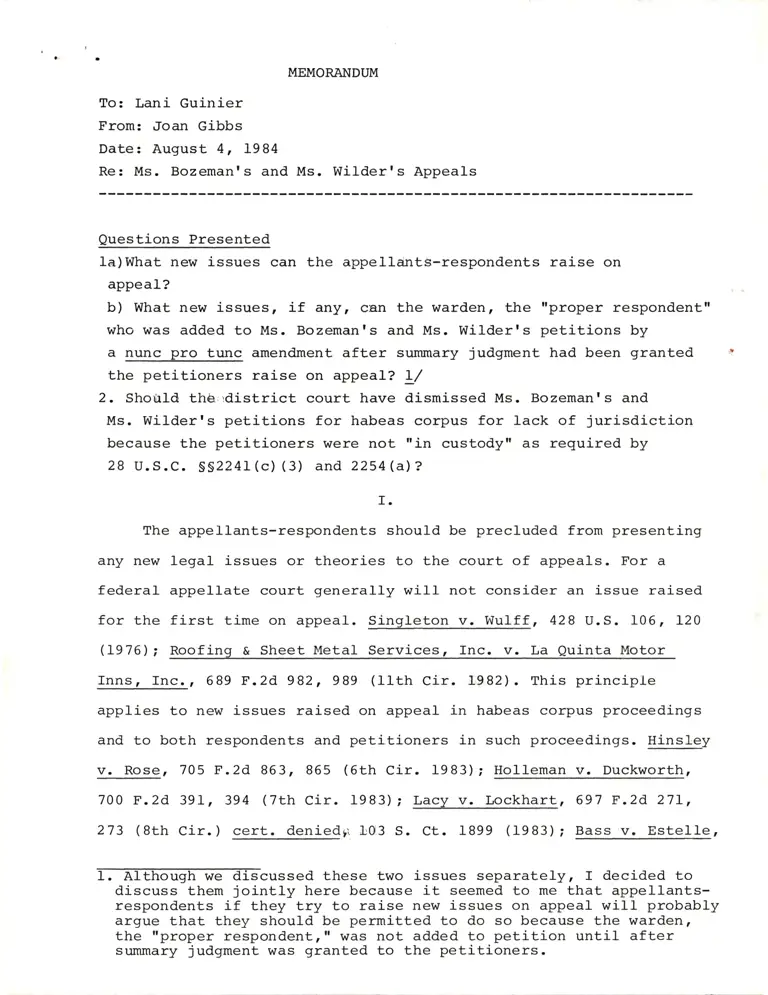

MEMORANDUM

To: Lani Guinier

From: Joan Gibbs

Date: August 4, 1984

Re: Ms. Bozemanrs and Ms. Wilderts Appeals

Questions Presented

la)What new issues can the appellant5-respondents raise on

appeal?

b) What new issues, if atry, can the warden, the "proper respondent"

who was added to Ms. Bozemanrs and Ms. Wilderrs petitions by

a nunc pro tunc amendment after sunmary judgment had been granted

the petitioners raise on appeal? L/

2. Shorlrld thb,rdistrict court have dismissed Ms. Bozemanrs and

Ms. Wilderrs petitions for habeas corpus for lack of jurisdiction

because the petitioners were not "in custody" as required by

28 U.S.C. SS22 1(c) (3) and 2254(a)?

r.

The appellants-respondents should be precluded from presenting

any new 1egal issues or theories to the court of appeals. For a

federal appellate court generally will not consider an issue raised

for the first time on appeal. Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106, L20

(1976) i Roofinq & Sheet Metal Services, Inc. v. La Quinta Motor

Inns, Inc., 689 F.2d 982, 989 (IIth Cir. 1982). This principle

applies to new issues raised on appeal in habeas corpus proceedings

and to both respondents and petitioners in such proceedings. Hinsley

v. Rose, 705 F.2d 863, 865

700 F.2d 391, 394 (7th Cir.

(6th Cir. 1983); Holleman v. Duckworth,

1983); Lacy v. Lockhart,

r03 s. ct. 1899 (1983);

697 F.2d, 271,

Bass v. Este11e,273 (8th Cir.) cert. deniedjr

@ussedthesetwoissuesseparate1y,Idecidedto

discuss them jointly here because it seemed to me that appellants-

respondents if they try to raise new issues on appeal will probably

argue that they should be permitted to do so because the warden,

the "proper respondentr " was not added to petition until after

sunmary judgment was granted to the petitioners.

696 F.2d 1154, 1159 (5tn Cir. 1983); Ford v. Strickland, 696 F.2d

804, 819 (Ilth Cir. 1983); Washington v. Walkins, 655 F.2d L364,

1368, (5th ,Cir.) rehearing denied 662 E.2d 1116 (1981); Robinson v.

Berman, 594 F.2d I (lst Cir. L979) i Tifford v. Wainwright, 592 F.2d

233, 234 (L979) . Although the defense of failure to join an

ind,ispens5rble party under RuIe 19 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure can be raised sus sponte by a court of appeab or by .the

appenrlantsr iLidd" .r. ,tO.n.U, 707 F.2d 1222, 1223-L234 (llth Cir.

1983); Kimball V. Florida Bar, 537 F. 2d 1305 (5th Cir. 1976) |

the appellants-respondents in the instant case should be precluded

from relyinging on Rule 19 either as a defense on appeal or as

a ggound for raising new issues because the warden is not an

indispensible party to the proceedings. Cervantes v. Walker, 589

F.2d 424 (9th Cir. L978)i West v. Louisana,478 F.2d l-026 (5th Cir.

7973) i Desousa v. Abram's.r 467 P. Supp. 511 (E.D.N.Y. L979);

United States:ex r€1. Gatuhreaux:'.v. State of l11inois, 447 F.-l-Supp.

500 (lt.o. r11. 1978).

The rule against consideration of new issues on appeal

derives primarily from "the needs of judicial economy and the

desirability of having all parties present their claims in the court

of first instant." Empire Life fnsurahce Cor. of America v. Va1dak

corp., 468 r'.2d 330, 334 (5th Cir. 1972). rt also reflects a

concern for avoiding prejudice to the parties. As the Supreme Court

explained in Hormel v. Helvering, 3L2 U.S. 552 (1941)

IOJur procedural scheme contemplates that parties

shaIl come to isse in the triat court forum vested

with authority to determine questions of fact.

Ihis j-s essential in order that parties may have

the opportunity to offer all evidence they believe

relevant to the issues which the trial tribunal

is alone competent to decide; it is equally

essential in order that litigants may not be

surprised on appeal by final decision there of issues

upon which they have had no opportunity to introduce

evidence.

Id. at 556.

The decision whether to consider an argument first made

on appeal, however, is "left primarily to the discretion of the

court of appeals, to be exercised on the facts of individual cases."

Singleton v. Wu1ff, 428 U.S. at L2L. Such discretion is necessary

because

[r]u1es of practice and procedure are devised to promote

the ends of justice, not to defeat them. A rigid

and undeviating judicially declared practice under whic$

courts of review would invariably and under all circumstances

decline to consider all questions which had not previously

been specifically urged would be out of harmony with this

policy. Orderly rules of procedure do not require sacrifice

of the rules of fundamental justice.

Hormel v. Helvering, 312 U.S. at 557. Thus, the Supreme Court

has indicated that it is appropriate for a federal appellate

,cour{to both consider and resolve an issue raised for the first

tj-me on appeal when resolution of the issue i-s beyond dispute or

where injustice might other:v,rise result. Singleton v. Wu1ff , 428

U.S. at 12I. Similarly, the Eleventh Circuit will consider an

issue raised for the first time on appeal if "the ends of justice

will best be served by doing So.rrEmpire Life Insurance Co. of

America v. Valdak Corp. , 468 F.2d at 334.2 Or more specifically,

the court will consider an issue not presentGd to the district

court if it involves a pure question of 1aw and if refusal to

consider it will result in a miscarriage of justice. Roofing

& Sheet Metal Services Inc., 689 F.2d at 990.

2, The Eleventh

of Prichard, 661

eircuit, in fhe en banc decision in Bonner v. cit

F.2d. t2oa (rtrr ffi9-er) adopred aslffir

ffiffiEffins of the former 5th Circuit decided prior to october

1, 1981. The 11th Cir. is also bound by all decisions of Unit B

of the former 5th Cir., Stein v. Reyno1dsr 667 F.2d 33, 34 (I1th

Cir. L982).

A "miscarriage of justice" will probably be found to be

lacking where the appellantts new argument is weak on the merits

,t ).

or the appellantr;wiII have another opportunity to make the argument

to the district court. Id. at 990 n. 11. Thtrs, the stage

at which the appeal is taken will effect the courtts determination

of whether or not the appellant should be heard on his new argument.

As Judge Wisdom, of the 5th Circuit, sitting by designation on

the l1th Circuit Court of Appeals, explained in RoofingT supr&.7

consideration of new issues in appeals from sunmary judgrments

are appropriate because in such cases the policiies behind the

rule against consideraLion of new issues on appeal are not impaired

by doing so.

Remand after reversal of summary judgment does not

seriously impair judicial economy, because, unlike

remand after triat, it does not involve the district

court in redunant proceedings. The party prevailing

on appeal must still present argunents with the

necessary evidentiary support to the trial

court if it is ultimately to prevail. And the burden

on the party that initially won sunmary judgment

is not comparable to that involved in remand

after the time and expense involved in a fuIl

trial.

Roofing & Sheet Metal Services, Inc. v. La Quinta Motor Inns.r Inc;

689 F.2d at 990.

With this in mind, the remainder of this memo will be

devoted to a discussion of some of the Supreme Court, former

Fifth Circuit, and Eleventh Circuit cases on this question. Particular

emphasis will be placed on chses in which either the respondents

or the petitioners in a federal habeas proceeding attempted to

raise a new issue on appeal.

Supreme Court Cases

The Supreme Court has both refused to consider issues raised

for the first time in that court and admonished courts of appeals

for considering issues not presented to the district court. Steagald

v. United States; Singleton v. Wulff, ggp5.. The Court, however,

has alsor EIS previously stated, vacated and remanded cases because

an issue, though raised on appeal, was not considered by lower

courts. Turn" , 396 U.S. 350 (L962) i Hormel

v. Helvering, supra.

In Steagald, a criminal defendant challanged federal drug

enforcement officials search of his home pursuant to an arrest

warranb for another individual. During the course of the search

drugs rn/ere found and the defendant was arrested on drug charges.

In the district court and before the court of appeals, the government

argued, inter a1ia, that the arrest warrant was sufficient to

justify the search of the defendantrs home and that the defendant's

connection with the house was sufficient to establish constructi-ve

possession of the covaine found in a suit case in'hi,closet in

the house. Steagald v. United States, 45L U.S. at 208-09. The

government put forth the same argument in its brief in opposition

to certiorari. Id. at 208. Subsequently, the government changed

its argument and contended that regardless of the merits of the Court

of Appeals'decisionrupholding the district courtrs refusal to

suppress the evidence seized during the search, the defendant

lacked an expectation of privacy in the house sufficient to

prevail on his Fourth Amendment claim. Id.

The Supreme Court refused to consider the governmentrs

new theory essentially because the argument had been available

to the government from the beginning. Justice Marsha11, writing

for the majority in Steagald, explained the Courtfs refusal to

aIlow the government to advance a totally new theory to the

Court as follows:

[T]he government was initially entitled to defend

against petitionerr s charge of an unlawful search

by asserting that petitioner lacked a reasonable

expectation of privalcy in the searched homer or that

he consented to the search t ot that exigent circumstances

justified the entry.i.

*

[D] uring the course of these proceedings the Government

has directly sought to connect the petitioner with the house

has acquiesced in statements by the courts below

characterLzing the search as one of petitionerrs

residence, and has made similar concessions of its

own. Nowri-.two years after the petitionerrs trial

the government seeks to retfun tne case to the district

court for a re-examination of this factual issue. The

tactical advantages to the Governemnt of this

disposition are obvious, for if the Government prevailed

on this claim upon a remand, it would be relieved

of the task of defending the judgment of the eourt

of Appeals before this Court.

Steagald v. United States, 45L U.S. at 210, 2LL

At least one court of appeals, the Court of Appeals for

the Seventh Circuit, has held the reasoning in Steagald inapplicable

to appeals by respondents in federal habeas proceedings. United

States ex re1. Cosey v. Wolff | 682 F.2d 691 (7th Cir. L9821.

In Cosey, the district court granted a writ of habaas corpus

to a state petitioner on the ground that the petitioner had been

denied effective assistance of counsel at his trial. Id. at 693.

Before the district courtT the respondent argued that the failure

of the petitionerr s counsel to call witnesses was an exercise

of trial strategy. After the petitioner was granted sunmary judgment

the respondents switched their argument and in a motion for

reconsideration claimed that there was no evidence that the

petitionerts counsel had been unaware of the witnesses. Id. at

693. The district court refused to consider the respondents/

new lack of knowledge argument "apparently because it thought

it was precluded from doing so because in the state court

proceedings the State had not made the lack of knowledge argument.

United States ex rel. Casey v. Wo1ff, 682 F.2d 693. The district

court in reaching this conclusion cited Ulster County Court v. Al1en,

442 U.S. L40, L52-L54 (7979) and Steagald v. United States, g-gpra.,

for the proposition that a party cannot relitigate issues on

a basis other than that consistently maintained in prior proceedings.

Oh,rappeal, the Seventh Circuit reversed the district courtrs

decision. The district court judge, the court of appeals stated,

had misunderstood the Supreme Courtrs decisions in Allen and

SteagaId.

...In AIIen, the Supreme Court decided it could

review a constitutional claim even though that claim

was raised for the first time in state proceedings

only after the jury announced its verdict. The

Supreme Court would not have considered a constituti-onal

issue raised after the verdict if there adequate and

independent state grounds for the state court decision.

The Supreme Court concluded that there were not

adequate and independent state grounds. The Steagald

case deals with a party changing its position on appeal,

and of course a habeas corpus proceeding is not an

an appeal of a state court decision.

United States ex reI Casey v. Wolff, 682 F.2d at 694 (citations

omitted). The court then went on to reject the appeileers novel

elaj-m that the Supreme Court's decision'in Rose v. Lundy, 455 U.S.

509 (1982), holding that habeas petitions which contained exhaus.bed

and unexhausted claims must be dismissed in their entirety, also

precluded respondents in habeas proceedings from raising claims

not presented to state courts.

This argument shows a misunderstanding of the nature

of the Grda,t Writ. The purpose of the exhaustion

requirement, based on principles of comity,

is to minimize friction between state and federal

judicial systems by reducing the instances in which

federal courts upset a state court conviction. These

principles are not applicable when the argument

raised for the first time in federal courts asks

that the state court action not be changed.

United St.at€s ex reI. Casey v. Wolff | 682 F.2d at 694. As

discussed infra, however, most courts have refused to allow

respondents, absent a showing of exceptional circumstances to

raise a new issue on appeal.

In Singleton V. Wulff, supra., a group of Missouri

doctors brought an action challenging the constitutionality of

a state statute that provided Medicaid benefits only for

medically indicated abortions. The district court granted

the defendant's motion to dismiss on the ground that the

plaintiff's lacked standing. On appeal, the 8th Circuit

concluded that the doctors had standing and that the challenged

statute was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court agreed with the 8th Circuitrs conclusion

that the plaintiff's had standing to challenge the statute.

The Court, however, reversed and remanded the case because the

Court of Appeals had erred in proceeding to the merits of the

case, since the petitioner had not filed an answer or other

pleading addressing the merits and had not had the opportunity

to present evidence or lega1 arguments in defense of the

statute. Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. at I20-

The court in singleton cited Iurner, supra., and Hormel

as examples of cases involvinq "circumstances in which a

federal appellate court is justified in resolving an issue

not passed on below." Id. at l-2l-. In a footnote, however, the

Court noted that "these examples are not intended to be exclusive."

Turner was a 1983 class action challenging the refusal

of a resturant located on property leased from the city of Memphis

to provide nonsegregated services to Black people- The

defendant's answer invoked state statutes authorizing a state

agency to issue regulatJ-ons governing the safety and sanitation

of resturants, and making violations of such regulations

a misdemeanor, dS well as regulations requiring segregation

of Black and white people in resturants. Tur:ner rhoved for

summary judgrment, and the single judge convened a three-judge

court, which ordered the suit held in abeyance pending a suit

in state court for interpretation of the statutes. The Supreme

Court, oD appeal, vacated the district courtrs order and remanded

the case to that court with directions to enter a decree granting

injunctive relief to the plaintiff. The supreme court did not

remand the case because the proPer resolution was beyond any

doubt.

On the merits, no issue remains to be

resolved. This is clear under prior

decisions and the undisputed facts

of the case. Accordingly no occasion is

presented for absention, and the.litigation

ihould be disposed of as expeditiously

as is consistent with proPer judicial

administration.

Turner v. City o;[ llemphis, 369 U'S' at 354'

Hormel concerned an attempt by the commissioner of

Internal Revenue to switch the statutory basis of his argument

for assessing a deficiency ggainst an individual taxpayer' The

court of Appeals considered the commissioner's new argument

and reversed the decision of the United States Board of Tax

Appeals settinq aside the deficiency'

(E-

The Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Appeals'

decision but remanded the case to the Board of Tax Appeals

because Congress had vested it with exclusive authority

to determine disputed facts in tax cases. Horme1 v. Helvering,

3L2 U.S. at 350. The Court gave two reasons for why the

Court of Appeals' consideration of the Commissioner's new

Iegal theory had been appropriate. First, while the ease

\^ras pending before the court of appeals, the Supremb Court

had handed down a decision inf€rprpting,the statutes at issue

in Hormel, which if it had been "applied might have materially

altered the resu1t. " Id. at 558-559. 'EFcisions not in accordance

with lawr" the Court said, "should be modified, reversed and

remanded ras justice may require.'" Id.

Second, strict application of the principle that an

appellate court should not consider a new argument on appeal

in Hormel would have resulted in the "defeat rather than [the]

promot[ion] [of1 the ends of justice." Id. at 560. This

was because it would have allowed the petitioner to "wholIy

escape payment of a tax which under the record before us

he clearly owes." Id.

J)

Circuit Court Decisions

There are a substantial number of cases in every circuit in

which courts refused to a1low petitioners to raise new arguments

on appeal. See e.g. Hensley V. Rgse, supra (claim that state

habitual offender statute infringed right to testify not addressed

by state or district court and therefore not addressed on appeal);

Holleman v. Duckworth, supra (c1aim that confessi-on involuntary

due to drug withdrawal not presented to district court and there-

fore not addressed on appeal); Lacy v. Lockhard, supra (petitioner

precluded from raising on appeal claim that attorney was incompetent

because issue not addressed by district court). Not surprisingly,

however, gJ-ven the 1ow success rate of petitioners in habeas

corpus proceedingsr there are not a large number of cases in which

respondents and not petitid.ners tried to raise a new issue on

appeal. Washington v. Walkins, supra, Robinson v. Berman, .supm..

The reasoning that the courts have applied, however, in refusing

to allow petitioners to raise new issues on appeal is equally

applicable to respondents.

Respondents have been barred from raising for the first

time on appeal claims that petitioners failed to exhaust state

remedies, failed to properly present their claims to state courts,

or procedurally defaulted on a claim. fn Washington v. Walkins,

supra, the defendant was convicted of capital murder and sought

a petition for habeas corpus on the ground that the jury instruc-

tions during the sentencj-ng phase were invalid. For the first time

on appeal, the state argued that the defendant r had waived his

claim because his trial counsel expressJ.:y declined to voice an

objection. Washington v. Walkins, 655 F.2d at 1368. The court

refused to consider this argument, stating

Werfind two flaws in the Staters Sykes argument. First,

the State did not contend in the district court that

Washington's Lockett claim is barred by MississiPpi's

contemporaneoliE-ffiction rule and Sykes. As such, the

state itself is precluded from raising at this late

any cliam that Washington should be barred under a state-

1aw theory of procedural default, for ' [a] s a general

principle of appellate review this court will not consider

a legal issue or theory that was not presented to [the

federal district courtl I Noritake

Champi-on , 627 F.2d 724,

Washington v. Walkins, 655 f'.2d at 1368. See also Smith v. Estelle,

t1r tr

602 F.2d, 708 n. 19 (5tfr Clr. l.gTg) (state waived its Sykes

argument by failing to present it to the federal district court)

afftd 101 S. Ct. 1866, 68 L.Ed 2d 359 (1981); LaRoche v. Wainwright,

v. Wainwright, 599 F.2d 722, 724 (5th Cir. 1979) (same).

In Tifford, supra, the former Fifth Circuit upheld the

issuance of a writ of habeas corpus on the ground that the refusal

to grant the petitioner's motion for severance at trial rendered

his trial fundamentally unfair. The Florida Court of Appeals had

previously resolved this issue in favor of the state.

The state in Tifford in its original briefs before the

district court and the court of appeals took the position that the

Florida Court of Appeals' disposition had been limited soleIy

to issues of state 1aw. In its petition for rehearing, however,

the state changed its position and argued for the first time

that the state court had resolved the federal constitutional ,.Ad;

ddversely to the petitioner and that this determination was

binding on the federal court. Tifford v. Wainwright | 592 F.2d at

233-234. In short, the state switched from arguing failure to

exhaust state remedies to claiming that the federal district

court had failed to accord the state courtrs decision proper

deference. The Fifth Circuit declined to to consider the staters

Hellancic

new contention stating that

Arguments not made to the district court

will not be considered on appeal exceptrwhere the interests of substantial justice

;i::ili":5::"n:i" ::ii'riilirl$:i":xhs :ur i,.,

lhe new contentions are not based on any new

developments in the law or any newly unearthed

facts.

Tiffird v. Wainwright t 592 F.2d at 234(citations omiiited).

In Messelt v. State of A1abama, 595 F.2d 247 (5th Cir. L979) ,

a petitioner appealed the dihbricb courtr s de<iision denying his

application for a writ of habeas corpus. In the district court,

the state never challenged the petitioner's claim that hd;

had exhausted aviblable state remedies and litigated the case

as if the petitioner had exhausted his state remedies. When the

state sought to raise the issue of failure to exhaust on appeal,

the Court of Appeals declined to hear it, stating that " [t]his

is too little too late." Messelt v. State of A1abamar 595 F.2d

at 250. "As a general ruIe, contentions urged for the first time

before this CourtrI the Court of Appeals continued, "are not

properly before us on an appeal from the derilial of relief under

28 U.S.C. 52254, From a standpoint of orderly judicial procedure,our

appellate function in such appeals is clearly limited to reviewing

matter which have not been presented to the Distict Court. rr Id.

at 25A=25L. (citations omitted).

b.

The fact thatl.Lthe wa.rden wa5 added to the petiti-oners! '

petition after sunmary judgrnent was granted to petitioners should

not be suffj-cient ground for the court to deviate from the

general practice of not considering new issues on appeal. The warden

/1

is not an indispensible party to the proceedings. For as the court

noted in West v. Lousiana, 47 8 F.2d 1026 (5th Cir. 1973) ,

ltlhe warden [has] nob interest in the proceeding

independent of that of the State. By supplying

the locus of his detention, together with other

information required by the standard form for

habeas petitions, West furnished sufficient

information to enable the stater s attorney I s

to represent the interests of the State and the

warden, and to enable the court to frame a proper

order. There is therefore no reason not

to consider his petition as though he had named

the proper respondent.

Id. at 1030. Several courts sj-nce ECE! was decided have either

explicitly held that the failure to name the proper respondent

in a petition for habeas corpus did not constitute a violation of

Rule 19 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or have proceeded

to treat the petitionerrs petition as if the proper respondent had

been named. Cervantes v. Walker, 589 F.2d 424 (9th Cir. t978) i

Desousa v. Abrams | 467 F. Supp. 511 (E.D.N.Y. 19791 i Unj-ted

States ex relGatuhreaux v. State of Illinois, 447 F. Supp. 600

(N.D. I11. 1978); Thibobeau v. Commonwealth of Mass., 428 F. Supp.

542 (O. Mass. 1977). But see, Mackey v. Gonzalez , 662 F.2d 7L2

(lIth Cir. 1981); Spence v. Cundiff, 4I3 F. Supp. l-246 (W.D. Va.

L976) .

In Thibobeau, E-W,., a state petitioner brought a petition

plead both as petition for habeas corpus and a civil rights action

under 42 U.S.C. 51983. The respondents moved to dismiss the the

petitioner's petition on the ground, inter alia, that the petition

failed to join an indispensible party as required by Rule 19. The

court, though denying relief to the peti-tioner, rejected this

argument.

an amendment to the petition, sr:bstituting

the superintendent of the institution where he

is confined as respondent.

Desousa v. Abrams, 467 E. Supp. at 513.

The appellants-respondents may try to distinguish some of

the above cases on the ground that the proper respondent was added

the petitionersr petitions i.n some of':the cases before the

respondents answered was filed (.e.9. Desousa) and not after sunmary

j udgment had been granted to the petitioners. Th6re areir trrso

responses that can be made to this argument based upon the above and

other cases. First, the warden was added to the petition after

sunmary judgment by a nunc pro tunc amendment which has the effect

of reaching back to the time the petition was filed. See e.![.

Kirtland v.. J. Ray McDermott & Co., 568 F. 2d 1L66, 1169 n..5 .:

(5trr Cir. 1978). Second, even if the warden had not been added

to the petitionerrs petition, the court should still not vacate

the district courtrs decision and remand the case or permit the

respondents to raise new issues on appeal because the wardenf is

not an indisepensible party. For the isardertr has no interest ,.

indep.endenb of the previously named respondents, all the defenses

that could have been asserted by the warden were available to

the respondents below and the parties are all represented by l

members of the same state attorneyrs office.

l4bir Bozemants and Ms. Wilderrs case is also distinguishable

from those cases in which petitioners failure to name the proper

respondent constituted grounds for dismissal. Forrunlike the

petitioner in Spence v. Cundiff, E-8, Ms. Bozeman and Ms. Wilder

did not name the sentencing judge who had "neither the power

or arithority to order the petitioner released under a federal writ

of habeas corpus." Spence y. Cundiff, 4L3 F. Supp. at L247.

Rather, the petitioners I named the Board of Pardon and Paroles

who does after the power to grant the relief requested by the

petitioners.

One new issue that the warden may try to raise on appeal

is that Ms. Wilderts and Ms. Bozemanrs petiti,ions for habeas

corpus should have been dismissed by the district court for lack

of jurisdiction because the petitioners were not"in custody"

as required by the federal habeas corpus statutes. See e.g.

Duvalliorl v. Florida, 691 F.2d 483 (lIth Cir. 1982). For at the

time the district court granted sunmary judgment to the petitioners

their parole terms had expired.

This argument if raised by the appellants should not

be difficult to refute. First, it should he pointeilloutihhat the

Supreme Court has consistently held that petitioners on parole

were "in custody[ for the purpose of the federal habeas corpus

statute. See,r€.9. Justices of Boston lluntcipal Court v. Lyndon,

U. S. , 52 U.S.L.W. 4460 (Apri1 L7, 1984); JpneE_ v:

Cunningham, 37L U.S. 236 (1963). Second, it should be argued that

the custody requirement j-s satisfied if at the time the petitioner

applies for the writ he is in custody and that the petitionerrs

sr:bsequent release does not defeat jurisdiction. Carafas v. LaVallee,

391 u.S. 234 (1968).

Mh. Bozdrtrin and Ms. Wilder, unlike the petitioners the

Duvallion v. Etg4darsupra. and Westberry v. Keitht 434 T.2d 623

(5th Cir. 1970), were not merely subjected to a "fine;'"