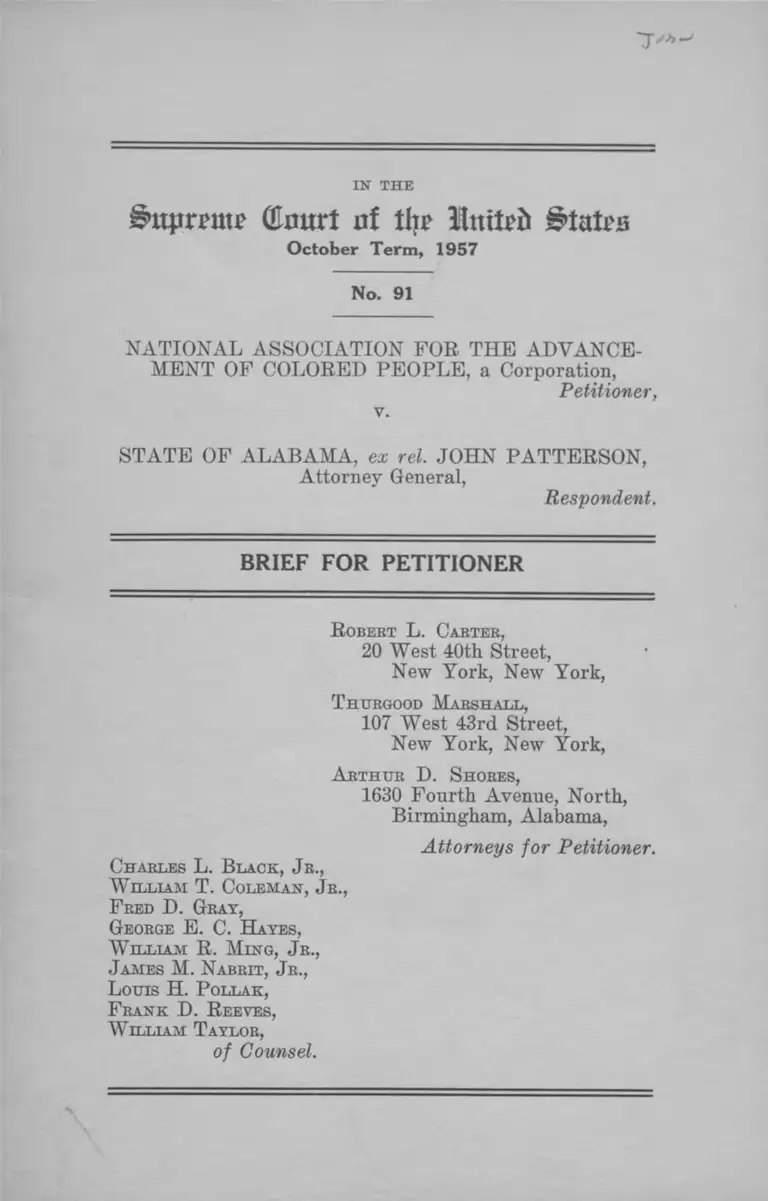

NAACP v. Alabama Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Brief for Petitioner, 1957. 69850922-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ad3524b4-5d69-4314-8e84-048e20a2eb77/naacp-v-alabama-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

irtprium.' (Emtrt nf th? Inited States

October Term, 1957

No. 91

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCE

MENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF ALABAMA, ez ret. JOHN PATTERSON,

Attorney General,

Respondent.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

R obert L. Carter,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

T hurgood Marshall.,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

A rthur D. S hores,

1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

Charles L. B lack, Jr.,

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.,

F red D. Gray,

George E. C. H ayes,

W illiam R. M ing, Jr.,

James M. Nabrit, Jr.,

L ouis H. P ollak,

F rank D. R eeves,

W illiam T aylor,

of Counsel.

I N D E X

Opinion B e low ................................................................ 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 1

Question Presented ...................................................... 2

Statement ........................................................................ 2

Petitioner’s Background and General Organiza

tional Activities ................................................. 2

Petitioner’s Background and Organizational

Activities In A labam a....................................... 7

The Instant Proceedings....................................... 8

The Climate in Alabam a....................................... 12

Summary of Argum ent................................................. 18

Argument ........................................................................ 21

I— The Fourteenth Amendment Prohibits the

State From Interfering With the Activities

of Petitioner ...................................................... 21

II— Purporting to Enforce Its Foreign Corpora

tion Registi’ation Statutes, the State Has Here

Acted to Prohibit Petitioner and Its Members

from Exercising Rights Guaranteed hy the

Fourteenth Amendment..................................... 32

III— Taken As A Whole the Proceedings Were

Lacking in Fundamental Fairness Essential

to Our Concept of Due Process of L a w .......... 38

Conclusion ...................................................................... 49

PAGE

Table o f Cases

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 6 1 6 ................... 22

Alabama G. S. R. Co. v. Taylor, 129 Ala. 238, 29 So.

673 (1901) .................................................................. 46

American Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U. S.

382 ................................................................................. 30, 31

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 ............................... 32

Benitez v. Anciani, 127 F. 2d 121 (1st Cir. 1942), cert.

den. 317 U. S. 699 ...................................................... 39

Betts v. Brady, 316 U. S. 455 ....................................... 38

Birmingham Bar Association v. Phillips & Marsh,

239 Ala. 650, 196 So. 725 (1940) ............................. 34

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 ......................... 31

Brotherhood of Railway & Steamship Clerks v. Vir

ginia Ry. Co., 125 F. 2d 853 (4th Cir. 1942)........... 28

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ............... 6

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ............................. 18, 21, 25

Cadden-Allen Inc. v. Trans-Lux News ,254 Ala. 400,

48 So. 2d 428 (1950) ................................................. 33

Carden v. Ensminger, 329 111. 612, 161 N. E. 137

(1928) ........................................................................... 45,46

Chandler v. Taylor, 234 Iowa 287, 12 N. W. 2d 590

(1944) ........................................................................... 46

Columbia Pictures Corp. v. Rogers, 81 F. Supp. 580

(S. D. W. Va. 1949) ....................................... 47

Corte v. State, 259 Ala. 536, 67 So. 2d 782 (1953) .. 41

Darring, Ex parte, 242 Ala. 621, 70 So. 2d 564 (1942) 45

Daves v. Hawaiian Dredging Co., 114 F. Supp. 643

(D. Hawaii 1953) ..................................................... 47

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 22 ................................. 1; 2

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ......................... 18, 21, 27

Dennis v. United States, 341 U. S. 494 ..................... 30

11

PAGE

I ll

Drake v. Herman, 261 N. Y. 414, 185 N. E. 685 ........ 45, 47

Dorchy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306 ............................... 1, 2

Eilen v. Tappin’s Inc. et al., 14 N. J. Super. 162, 81

A. 2d 500 (1951) ........................................................ 46

Farmers Savings Bank v. Murphee, 200 Ala. 574, 76

So. 932 (1917) ............................................................ 37

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315 ............................... 31

Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191 ................................... 8

Firebaugh v. Traff, 353 111. 82, 186 N. E. 526 (1933) 45,46

Flanner v. St. Joseph Home for Blind Sisters, 227

N. C. 342, 42 S. E. 2d 22 (1947)............................... 46

Floridin Co. v. Attapulgus Clay Co., 26 F. Supp. 968

(D. Del. 1939) ............................................................ 47

Follett v. McCormick, 321 U. S. 573 ........................... 25, 31

Francis v. Scott, 260 Ala. 590, 72 So. 2d 93 (1954) . . . 41

Frank v. Marquette University, 209 Wis. 372, 245

N. W. 145 (1932) ...................................................... 46

Frasier v. 20th Century Fox Film Corp., 119 F. Supp.

495 (D. Nebr. 1954) ’. ................................................... 47

Galvan v. Press, 347 U. S. 522 ..................................... 38

Garner v. Board of Public Works, 341 U. S. 716 . . . . 19, 30

Garner v. Teamsters C. H. Union, 346 U. S. 485. .19, 25, 30

Gayle v. Browder, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

a ff’d 352 U. S. 903 .................................................6,8,10,34

Gebhard v. Isbrandtsen Co., 10 F. B. D. 119 (S. D.

N. Y. 1950) ................................................................ 45

Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U. S. 325 ............................. 22

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 ............................... 22, 31

Goldner v. Chicago & N. W. By. System, 13 F. B. D.

326 (N. D. 111. 1952) ................................................. 45

Grater Mfg. Co., In re, 111 NLBB No. 20 (1955) . . . . 28

Griffin Mfg. Co. Inc. v. Gold Dust Corp., 245 App.

Div. 385, 292 NYS 931 (2d Dept. 1935)

PAGE

47

IV

Griffith v. State, 19 S. W. 2d 377 (Tex. Civ. App.

1929) ............. 40

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 .......... 21

Gulf Compress Co. v. Harris Cortner & Co., 158 Ala.

343, 48 So. 477 (1909) ............................................... 37

Haffenberg v. Windling, 271 App. Div. 1057, 69 NYS

2d 546 (4th Dept. 1947) .......................................... 46

Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496 ...................................................................... 22

Hardeman v. Donaghey, 170 Ala. 362, 54 So. 172

1911) ............................................................................ 37

Hawley Products Co. v. May, 314 111. App. 537, 41

N. E. 2d 769 (2d Dist. 1942) ................................... 46

Hercules Powder Co. v. Rohm & Haas Co., 4 F. R. D.

452 (D. Del. 1944) .................................................... 47

Herring v. M ’Elderry, 5 Port. 161 (1837) ................ 37

Hill, Ex parte, 229 Ala. 501, 158 So. 531 (1935) . . . . 43

Hill v. Florida, 325 U. S. 538 .....................................19, 25, 30

Hogan v. Scott, 186 Ala. 310, 65 So. 209 (1914 )........ 37

Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S. 460 ................. 25, 30

In re Grater Mfg. Co., I l l NLRB No. 20 (1955) . . . . 28

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Vogt,

Inc., 354 U. S. 284 ....................................................... 25

International Nickel Co. v. Ford Motor Co., 15 FRD

357 (S .D .N .Y . 1954)................................................. 47

International Union v. Wisconsin Employment Rela

tions Board, 336 U. S. 245 ....................................... 23

Jacobs v. Jacobs, 50 So. 2d 169 (S. Ct. Fla. 1951) . . . 46

Jacoby v. Goetter Weil Co., 74 Ala. 427 (1883) . . . . 37, 42

Jarrett v. Hagerdorn, 237 Ala. 66, 185 So. 401 (1939) 37

Jefferson Island Salt Co. v. Longyear Co., 210 Ala.

352, 98 So. 119 (1923)................................................. 33

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123 ............................................................. 19,21,32

PAGE

V

Jones v. Martin, 15 Ala. App. 675, 74 So. 761 (1917) 33

June v. George C. Petei-son Co., 7 Fed. Rules Serv. 34

(N. D. 111. 1942) ........................................................ 47

Kaplan v. Roux Laboratories, Inc., 273 App. Div.

865, 76 NYS 2d 601 (2d Dept. 1948) ..................... 47

King, Ex parte, 263 Ala. 487, 83 So. 2d 241 (1955) .. 43

Kingsley Books v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436................. 25

Kittaning Brewing Co. v. American Natural Gas Co.,

224 Penna. 129, 73 Atl. 174 (1909)........................... 40

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252 2

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 ................................. 31

Kullman, Salz & Co. v. Superior Court, 15 Cal. App.

276, 114 P. 589 (1911) ............................................... 45

Lever Bros. Co. v. Proctor & Bambie Mfg. Co., 38 F.

Supp. 680 (D. Md. 1941) ........................................... 47

Los Angeles Transit Lines v. Superior Court, 119 Cal.

App. 2d 465, 259 P. 2d 1004 (1953)......................... 46

McClatchy Newspapers v. Superior Court, 26 Cal.

(2d) 386, 159 P. 2d 944 (1945) ............................... 46

McCullough v. Walker, 20 Ala. 389 (1852) .............. 37

McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U. S. 203 . . . . 31

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 6

Martin v. Capital Transit Co., 170 F. 2d 811 (C. A.

D. C. 1948) .................................................................. 45

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141.............................. 31

Mayor v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877 ................................. 6

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . 6

Mitchell v. Wright, 154 F. 2d 580 (5th Cir. 1946).. 8, 34

Momand v. Paramount Pictures Distributing Co.,

36 F. Supp. 568 (D. Mass. 1941) ............................. 47

Mongogna v. O ’Dwyer, 204 La. 1030, 16 So. 2d 829

(1943) .......................................................................... 40

Murdock v. Pennsyvania, 319 U. S. 105 ..................... 25, 31

PAGE

VI

National Broadcasting Co., Inc. v. United States, 319

U. S. 1 9 0 ...................................................................... 21

National Labor Relations Board v. Essex Wire Co.,

245 F. 2d 589 (9th Cir. 1957) ................................. 19, 27

National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin

Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1 ........................................... 21

National Labor Relations Board v. Minnesota Min

ing & Mfg. Co., 179 F. 2d 323 (8th Cir. 1950) . . . . 28

National Labor Relations Board v. National Plastics

Products Co., 175 F. 2d 755 (4th Cir. 1949).......... 20,27

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ................................. 25

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ......................... 22

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319 ......................... 22

Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454 ....................... 22

Patterson v. Southern Ry. Co., 219 N. C. 23, 12 S. E.

652 (1941) .................................................................. 45,46

Pennekamp & Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Flor

ida, 328 U. S. 3 3 1 ........................................................ 21, 22

Pepperell Mfg. Co. v. Alabama Nat’l Bank, 261 Ala.

665, 75 So. 2d 665 (1954) ......................................... 33

Perfect Measuring Tape Co. v. Notheis, 93 Ohio App.

507, 114 N. E. 2d 149 (Ct. App. Lucas Co., 1953) .. 47

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 . . . . 19, 21, 22, 32

Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530 . . . 22

Pyle v. Pyle, 81 F. Supp. 207 (W. D. La. 1947) . . . . 47

Reeves v. Alabama, 348 U. S. 8 9 1 ............................... 8

Rochell v. Florence, 236 Ala. 313, 182 So. 50 (1938) 39

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U. S. 226 ............................. 1, 2

Roth v. United State, 354 U. S. 476 ............................. 25

Rowell, Ex parte, 248 Ala. 80, 26 So. 2d 554 (1946).. 46

Royster v. Unity Life Ins. Co., 193 S. C. 468, 8 S. E.

2d 875 (1940)

PAGE

46

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 ................................. 31

Shell Oil Co. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles

County et al., 109 Cal. App. 75, 292 P. 531 (1930) 45,46

Sims v. Green, 160 F. 2d 512 (3d Cir. 1947).............. 39

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 6 3 1 .................. 6

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ............................... 6

Southard & Co. v. Salinger, 117 F. 2d 194 (7th Cir.

1941) ............................................................................. 39

Spector Motor Co. v. O ’Connor, 340 U. S. 602 ----- 33

State v. Aronson, 361 Mo. 535, 235 S. W. 2d 384

(1950) .......................................................................... 45,46

State v. Flynn, 257 S. W. 2d 69 (S. Ct. Mo. 1953) . . . 45, 46

State v. Hall, 325 Mo. 102, 27 S. W. 2d 1027 (1930) .. 45, 46

State v. Oden, 248 Ala. 39, 26 So. 2d 550 (1946)........ 34

State ex rel. Scott v. U. S. Endowment & Trust Co.,

140 Ala. 610, 37 So. 442 (1903) ............................... 34

State ex rel. Johnson v. Southern Bldg. & Loan Assn.,

132 Ala. 50, 31 So. 375 (1902) ................................. 34

Steverson v. W. C. Agee & Co., 13 Ala. App. 448, 70

So. 298 (1915) ........................................................... 45,46

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ..................... 22

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................... 6

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234. .18,19, 21, 22, 23,

24, 26, 27, 29, 31, 48, 49

Szubinski v. Commercial Sash & Door Co., 15 F. R. D.

274 (N. D. 111. 1953) ................................................ 45

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ........................... 18, 31

Texarkana Bus Co. v. National Labor Relations

Board, 119 F. 2d 480 (6th Cir. 1941) ................... 27

Theard v. United States, 354 U. S. 278 ................... 19, 23

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 5 1 6 ....................... 18,19, 25, 31

Thomas v. Trustees of Catawba College, 242 N. C.

504, 87 S. E. 2d 913 (1955) ....................................... 46

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 ........................... 22

Times-Mirror Co. v. Superior Court, 314 U. S. 252.. 21

V ll

PAGE

via

Toth v. Bigelow, et al., 12 N. J. Super. 359, 79 A. 2d

PAGE

720 (1951).................................................................... 45,46

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 3 3 ......................................... 32

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75 . . . . 31

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 6 1 2 ................... 18

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41 ..............18,19, 23, 25,

26, 27, 29

United States v. United Mine Workers of America,

330 U. S. 258 ........................................................... 42,43,44

Wagner Mfg. Co. v. Cutler-Hammer, 10 F. R. 13. 480

(S. D. Ohio 1950) .................................................... 47

Walker v. Hutchinson, 352 U. S. 1 1 2 ......................... 38

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 ........18,19, 22, 23,

25, 26, 27, 32, 48, 49

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 148 ............... 18, 23, 24, 27

White v. Skelly Oil Co., 11 F. R. D. 80 (W. D. Mo.

1950) ............................................................................ 46

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ......................... 22

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ............................. 49

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 2 5 ................................... 38

Woods v. Kornfeld, 9 F. R. D. 678 (M. D. Pa. 1950) 46

37Youngblood v. Youngblood, 54 Ala. 486 (1875)

Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U. S. 306 ................................. 31

IX

Statutes

Alabama Code of 1940:

Title 7, Section 426 ................................................ 44

Title 7, Sections 474(1)-474(18) ......................... 44

Title 7, Section 757 ................................................ 41

Title 10, Sections 192, 193, 194 ........................... 9, 32

Title 10, Sections 192-195 ...................................... 35

Title 10, Sections 196-198 ...................................... 36

Title 13, Section 1 4 3 ................................................... 43

Constitution of Alabama, 1901, Article 12, § 232 . . . . 8, 32

Other Authorities

103 Cong. Rec. 85th Cong., 1st Sess. 1957, A. 5888,

5889 ............................................................................... 40

7 Cyclopedia of Federal Procedure 605-606 ............... 46

7 Cyclopedia of Federal Procedure 609-610 (3rd ed.

1951) ................................................................................. 45

7 Cyclopedia of Federal Procedure 6 4 1 ..................... 46

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 3 4 ............................. 45

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 6 5 ............................. 39

Anno. 58 ALR 1263 ........................................................ 46

4 Moore’s Federal Practice 2451 (2d ed. 1950 )........ 45

58 Yale Law Journal 574 (1949) ................................. 4

Latham, “ The Group Basis of Politics,” 1950 ............ 24

Skinner, “ Alabama’s Approach to A Modern System

of Pleading and Practice,” 20 FRD (Adv. pp. 119,

137) 1957 ......................................................................... 44

PAGE

X

Southern School News:

June 1955, Vol. I, No. 1 0 ....................................... 13,14

August 1955, Vol. II, No. 2 ................................... 13

September 1955, Vol. II, No. 3 ............................. 14

December 1955, Vol. II, No. 6 .................. 12

February 1956, Vol. II, No. 8 .................. 14

March 1956, Vol. II, No. 9 ..................................... 12

April 1956, Vol. II, No. 1 0 ................................... 12

June 1956, Vol. II, No. 1 2 ..................................... 12

July 1956, Vol. I ll, No. 1 ............................... 12

December 1956, Vol. I ll, No. 6 ................... 14,16

January 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 7 ......................... 13,14,16

February 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 8 ............................. 16

March 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 9 ................................... 15,16

April 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 1 0 ................................. 13,17

May 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 11................................... 14,15

June 1957, Vol. I ll, No. 1 2 ................................... 13,16

July 1957, Vol. IV, No. 1 ..................................... 15

August 1957, Vol. IV, No. 2 ................................. 12,17

September 1954-June 1955, Vol. I, Nos. 1-10 . . . . 15

July 1955-June 1956, Vol. II, Nos. 1 -12 .............. 15

July 1956-June 1957, Vol. I ll, Nos. 1 -12 ............ 15

New York Times, Sept. 10, 1957, p. 1, Col. 3 ............. 16

New York Times, Sept. 11, 1957, p. 23, Col. 3 ........... 16

Montgomery Advertiser March 4, 1957 (“ Off The

Bench” ) ....................................................................... 40

PAGE

IN THE

Supreme ( ta r t rtf tljr United States

October Term, 1957

No. 91

National, A ssociation fob the A dvancement of

Colored People, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

State of A labama, ex rel. John Patterson,

Attorney General,

Respondent.

---------------------- o----------------------

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 23)

is reported at 91 So. 2d 214.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the court below was entered on De

cember 6, 1956 (R. 31). On March 4, 1957, by order of

Mr. Justice Black, the time within which to file the petition

for writ of certiorari was extended to March 20, 1957. The

petition was filed on March 20, 1957, and was granted on

May 27, 1957. This Court has jurisdiction of this cause

under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1257(3) de

spite the effort of the Supreme Court of Alabama to inter

pose the state’s procedure to prevent review by this Court.

See Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S. 22; Rogers v. Alabama,

192 U. S. 226; Dorcliy v. Kansas, 272 U. S. 306. Part of

2

the petition for writ of certiorari was devoted to demon

strating that this case came within the rationale of those

cases. As petitioner reads the Brief in Opposition (page

9), respondent concedes the basic validity of this thesis,

and Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 353 U. S. 252,

underscores the fact that the Court has not departed from

the principles enunciated in Davis v. Weclisler, supra;

Rogers v. Alabama, supra, and cognate cases in its approach

to jurisdiction. Petitioner submits, therefore, that juris

diction to review this cause is unquestionably vested in this

Court and rests upon the argument in the petition for writ

of certiorari to support this position.

Question Presented

Did the State of Alabama interfere with the freedom

of speech and freedom of association and deny due process

of law to petitioner, the NAACP, and its members in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment in interfering with and

prohibiting the continuation of the efforts of petitioner to

secure and enforce rights of Negro citizens guaranteed by

the Constitution and laws of the United States?

Statement

Petitioner’s Background and General Organizational

Activities

Petitioner is a non-profit membership organization,

founded in 1909 and incorporated in 1911 under the laws

of the State of New York. The driving force which led to

its birth was the conviction that if the American public

became aware of the injustices which Negroes suffered and

the circumscribed lives which they were forced to lead

solely because of color discrimination, an aroused public

opinion would demand that necessary social, economic and

political reforms be effected to remove racial discrimina

tion and prejudice from American life. See Ovington,

“ How the NAACP Began” 8 Crisis 184 (1914); Kytle.

3

“ The Story of the NAACP,” Coronet 140 (August 1956);

“ What Is the NAACP,” 36 Information Service #8,

Bureau of Research and Survey, National Council of

Churches of Christ in the USA (Feb. 23, 1957). Since its

inception, the efforts of the organization and its members

have been directed exclusively towards finding adequate

ways and means of eradicating color and caste discrimina

tion from all facets of American life. See Wollman,

“ AVhat’s Behind the NAACP,” N. Y. World Telegram dc

Sun, May 12, 19, (1956); Davis, “ The NAACP: A Look

At the Record and Plans of One of the Nation’s Most Con

troversial Organizations,” Winston-Salem Sunday Jour

nal-Sentinel, Feb. 26, 1956; “ Segregation Conflict: Role

of the NAACP,” N. Y. Times, Feb. 26, 1956 E 9; “ Voice

of the Negro in America,” Milwaukee Journal, March 11,

1956; “ NAACP, Negro Champion, Sets ’63 Integration

Target,” Chicago Daily News, March 11, 1956; “ An Inter

view With NAACP Brass,” Montgomery Advertiser, June

26, 27, 1956.

Its Articles of Incorporation describe its aims and pur

poses as:

. . . voluntarily to promote equality of rights

and eradicate caste or race prejudice among the

citizens; to advance the interests of colored citizens;

to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to in

crease their opportunities for securing justice in

the courts, education for their children, employment

according to their ability and complete equality be

fore the law.

To ascertain and publish all facts bearing upon

these subjects and to take lawful action thereon;

together with any and all things which may lawfully

be done by a membership corporation organized

under the laws of the State of New York for the

further advancement of these objects.1

1 A copy of these Articles was filed with petitioner’s answer.

These and other allegations in the answer were summarized in the

petition for certiorari in the Supreme Court of Alabama, which

constitutes the record here.

4

Petitioner is committed to the achievement of desired

social, economic and political reforms within the frame

work of our democratic society. It seeks to create a cli

mate of opinion in which interracial understanding can

take place and basic rights and privileges will be accorded

to all persons without regard to race. From time to time

it attempts to persuade the legislature to adopt and the

executive to enforce remedial laws to provide protection

against racial discrimination, and to aid individuals to

vindicate their constitutional rights to freedom from dis

crimination in the courts wherever necessary.2

From the outset the organization has condemned racial

intolerance and disenfranchisement. It has sought to

secure public and legislative support for anti-discrimina

tion laws, e.ff., F. E. P. C. laws, anti-lynching laws, federal

and state civil rights laws. Its officials have testified on

the need for federal legislation of this kind before the

Congress and at various local legislative hearings.3 In

2 See, Note, Private Attorneys-General, 58 Yale L. J. 574 (1949).

3 For examples of this phase of petitioner’s activities see:

Segregation Hearings, H. J. Res. 75, House Judiciary Comm.

(66th Cong. 2d Sess. 1920) pp. 8-10 (Neval H. Thomas).

Anti-Lynching Hearings, S. 121, Subcommittee o f Senate Judi

ciary Comm. (69th Cong. 1st Sess. 1926) pp. 6-37 (James Weldon

Johnson); H. R. 259, House Judiciary Comm. (66th Cong. 2d Sess.

1920) pp. 22-27 (Arthur B. Spingarn); S. 1978, Subcommittee of

Senate Judiciary Comm. (73rd Cong. 2d Sess. 1934) pp. 62-67

(Arthur B. Spingarn).

Poll Tax Hearings, S. 1280, Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary

Comm. (77th Cong., 2d Sess. 1942) pp. 335-338 (Walter W h ite);

H. R. 7, Senate Judiciary Comm. (78th Cong. 1st Sess. 1943)

pp. 60-69 (Statements of William H. Hastie and Leon A. Ransom).

FEPC Hearings, S. 2048, Subcommittee of Senate Com. on

Education and Labor (78th Cong. 2d Sess. 1944) pp. 196-202 (Walter

White) ; S. 101, Subcommittee of Senate Comm, on Education and

Labor (79th Cong. 1st Sess. 1945) pp. 170-174 (William H. H astie);

S. 984, Subcommittee of Senate Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare, (80th Cong. 1st Sess. 1947) pp. 182-190 (Roy Wilkins) ;

5

1933 it established a full-time legal department whose func

tion was to formulate legal theories which could be utilized

H. R. 4453, Special Subcommittee of House Committee on Educa

tion and Labor (81st Cong. 1st Sess. 1949) pp. 293-300 (Clarence

Mitchell).

Civil Rights Bill Hearings, S. 83, Subcommittee on Constitu

tional Rights, Senate Judiciary Com. (85th Cong. 1st Sess. 1957)

pp. 291-326 (Roy Wilkins).

Grants to States for the Improvement of Public Elementary and

Secondary Schools Hearings, S. 1305, Subcomm. of Senate Comm, on

Education and Labor, (76th Cong. 1st Sess. 1939) pp. 178-184

(Charles H. Houston).

Federal Assistance for School Construction Hearings, H. Res. 73

(82nd Cong. 2d Sess. 1952) p. 352 (Letter of Clarence Mitchell).

Universal Military Training Hearings, H. R. 515, House Com.

on Military Affairs, (79th Cong. 2d Sess. 1946) pp. 940-948 (Leslie

S. Perry).

Universal Military Training Hearings, Senate Committee on

Armed Services, (80th Cong. 2d Sess. 1948) pp. 662-668 (Jesse O.

Dedmond, Jr.).

Military Reserve Training Hearings, H. R. 6900, (84th Cong. 1st

Sess. 1955) pp. 4260-4272 (Clarence Mitchell).

Amendments to Railway Labor Act Hearings, S. 3295, Subcom

mittee of Committee on Labor and Public Welfare (1950) pp. 242-

248 (Clarence Mitchell).

Amending the Interstate Commerce Act— Segregation of Passen

gers Hearings, H. R. 563 (83rd Cong. 2d Sess. 1954) pp. 96-118

(Robert Carter and Clarence Mitchell).

Economic Security Act Hearings, S. 1130, Senate Committee on

Finance (74th Cong. 1st Sess. 1935) pp. 640-647 (Charles H.

Houston).

Amendments to Fair Labor Standards Act Hearings, H. R. 3914,

House Committee on Labor (79th Cong. 1st Sess. 1945) pp. 441-448

(Leslie S. Perry).

Defense Housing Act Hearings, S. 349, Senate Committee on

Banking and Currency (82nd Cong. 1st Sess. 1951) pp. 477-481

(Clarence Mitchell).

Limitation on Debate in the Senate Hearings, S. Res. 41 (82nd

Cong. 1st Sess. 1951) pp. 34-64 (Walter White).

Habeas Corpus Hearings, H. R. 5649 ( 84th Cong. 1st Sess. 1955)

pp. 78-88 (Thurgood Marshall).

6

in the courts to secure relief against discriminatory gov

ernmental action and authorized the attorneys in the de

partment to participate directly as counsel in litigation

involving or raising questions of racial discrimination

where such requests were made by the litigant or his attor

ney, and where determination of the issues raised was likely

to affect the status of Negro Americans in general. Some

of the litigation in this Court for which petitioner is in

part responsible includes Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 U. S. 637; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629; Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Mayor

v. Dawson, 350 U. S. 877; Gayle v. Browder, 142 P. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956), aff’d, 352 U. S. 903.

Petitioner has chartered affiliates—designated as college

chapters, youth chapters, Branches and State Conferences

of Branches—throughout the United States. These affiliates

are unincorporated associations and membership therein,

upon acceptance at petitioner’s principal office in New York,

constitutes membership in the corporation. Each affiliate is

semi-autonomous, with its own officials and governing body,

and within the limits of the general directive (<to promote

the economic, political, civic and social betterment of col

ored people, and their harmonious cooperation with other

peoples, in conformity with the articles of the Association,

its Constitution and by-laws, and as directed by the Board

of Directors of the Association,” each determines for

itself the program it will follow at the local level (R. 7-8).4

Petitioner’s Board of Directors from time to time an

nounces general policy. Such a general policy was that

4 Constitution and bylaws of Branches of the N. A. A. C P

Article I, Section 2, March 1956.

7

adopted by the Board on October 9,1950, and by Convention

June 1951, forbidding all N. A. A. C. P. affiliates, officers

and members to participate in any effort to obtain “ sepa

rate but equal” facilities.

Petitioner’s Background and Organizational Activities

In Alabama

The first affiliates of petitioner in Alabama were char

tered in 1918. These were the Montgomery and Selma

Branches. Since that time petitioner has chartered various

other affiliates in Alabama and in April, 1951 established

a regional office in Birmingham, designated as its Southeast

Regional Office.

A Southeast Regional Secretary, whose chief duties are

to supervise and coordinate the programs of petitioner’s

various affiliates in Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi,

North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee, was placed

in charge of this office. She disseminates information to

members and to the general public concerning civil rights

and racial discrimination to seek to guide and assist peti

tioner’s various affiliates in the region in devising and

executing a program designed to eliminate racial discrimi

nation in their respective communities. Petitioner em

ployed a field secretary, and his duties were to interest

persons in Alabama in the aims, purposes and program

of the organization and to convince as many persons as

possible to take an active part in the effort to secure equal

rights for Negroes. Except for these two persons and

a clerical worker in the Birmingham office, all other persons

connected with the organization in Alabama, whether offi

cers or members, were unpaid volunteers (R. 7).

Petitioner rented office space in Birmingham for its

Southeast office and secured furniture and other office

equipment, but otherwise owns no property, real or per

sonal, in Alabama. The injunction here issued necessitated

8

the closing' of this office, the dropping of the field secretary

and clerical worker from petitioner’s payroll and the trans

fer of the Regional Secretary and petitioner’s Southeast Re

gional Office to another state.

Through its national office, its affiliates, and more re

cently its Southeast Regional Office, petitioner aided Ala

bama Negroes in seeking vindication of their constitutional

rights in the federal courts by helping to defray the

expenses of suits involving the right of Negroes to vote,

to equal access to nonsegregated facilities in public schools,

to non-discriminatory treatment in public transportation

facilities and to due process in criminal proceedings.

Among law suits in this category were Mitchell v. Wright,

154 F. 2d 580 (5th Cir. 1946); Gayle v. Browder, supra;

Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191; Reeves v. Alabama, 348

U. S. 891.

Petitioner engaged in these activities without complying

with Sections 192, 193, 194, Title 10, Alabama Code of

1940 and Article 12, Section 232, Constitution of Alabama,

1901, which require foreign corporations to register with

the Secretary of State, because petitioner in good faith

believed that these provisions did not apply to it (R. 8).

The first notice petitioner had that the state deemed it

subject to these statutes was the service of the temporary

restraining order and the complaint herein (R. 7), where

upon petitioner offered to register (R. 7).

The Instant Proceedings

Upon a bill of complaint filed by the Attorney General

of Alabama, which alleged in essence that petitioner was

giving aid and assistance to Alabama citizens in their

efforts to secure relief from racial discrimination and doing

and “ continuing to do business” within the state without

first having complied with Article 12, Section 232, Consti

9

tution of Alabama, 1901; Title 10, Sections 192, 193, 194,

Code of Alabama, 1940 and was “ thereby causing irrep

arable injury to the property and civil rights of the resi

dents and the citizens of Alabama for which criminal prose

cution and civil action at law afford no adequate relief,”

the trial court issued the requested restraining order ex

parte, barring petitioner from:

Soliciting membership in respondent corporation

or any local chapters or subdivisions or wholly con

trolled subsidiaries thereof within the State of Ala

bama.

Soliciting contributions for respondent or local

chapters or subdivisions or wholly controlled sub

sidiaries thereof within the State of Alabama.

Collecting membership dues or contributions for

respondent or local chapters or subdivisions or

wholly controlled subsidiaries thereof within the

State of Alabama.

And, although the state did not request it, from:

Filing with the Department of Revenue and the

Secretary of State of the State of Alabama any

application, paper or document for the purpose of

qualifying to do business within the State of Alabama

(R. 19).

On July 2, 1956, petitioner tiled a motion to dissolve

the injunction and demurrers to the bill (R. 3). Hearing-

on the motion to dissolve and the demurrers was set down

for July 17 (R. 3). On July 5, the state tiled a motion

for a pretrial discovery order to require petitioner to

disclose to the state the names and addresses of all of its

members and of all persons authorized to solicit member

ships ; all correspondence pertaining to or between peti

tioner and any person, corporation, etc., in Alabama; all

evidence of ownership of real and personal property held

by petitioner in the state; cancelled checks, bank state

ments, etc., showing any financial transaction between peti

10

tioner and persons, chapters, etc., in the state; all letters,

papers, correspondence, agreements between or pertaining

to petitioner and Autherine Lucy and Polly Ann Myers;

the names and addresses of all of its officers and employees

in the state; and all papers relating to or between Aurelia

S. Browder and the other plaintiffs in Gayle v. Browder,

their Alabama counsel and petitioner (R. 5-6). The state

alleged in its motion that examination of the requested

documents was essential to its preparation for trial (R. 3).

The state motion, given precedence over petitioner’s

pleadings, was heard on July 9 and granted on July 11

(R. 6), with petitioner being ordered to produce the docu

ments on July 16, 1957 (R. 6). (The order is set out at

R. 20.) The court extended the time to produce the docu

ments requested to July 24, 1956, and simultaneously con

tinued the hearings on the demurrers and motion to dissolve

from July 17 to July 25 (R. 6). On July 23 petitioner tiled

its answer, to which it attached executed foreign corpora

tion registration forms ready for filing with the Secretary

of State and asked the court’s permission to file same,

which permission was refused (R. 7). On the same date

petitioner filed a motion to set aside the order to produce,

which was set down for hearing on July 25. After such

hearing, on July 25th, the court denied petitioner’s motion

to vacate the order for pretrial discovery and, upon peti

tioner’s continued refusal to comply therewith, adjudged

it in contempt and fined it $10,000, with a proviso that if

the order was not obeyed within 5 days the fine was to be

$100,000 (R. 8-11).

On July 30, petitioner filed a motion to set aside and

stay execution of the contempt order pending its review

by the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 11). With this

motion petitioner tendered all documents requested except

the names and addresses of its members and its corre

spondence files. The latter request could not be complied

with because it was unduly burdensome for petitioner to

11

go through all its files and furnish correspondence re

quested and interfered with the normal operation of its

offices (R. 12). The former request was refused because

of petitioner’s belief that the order per se constituted an

abridgement of its rights and those of its members to

freedom of association and free speech, and because of its

belief that to comply with the order would subject petitioner

organization to destruction and its members to reprisals

and harassment, thereby effectively depriving petitioner

and its members ot the right to the exercise of freedom

of association and free speech—all in violation of their

constitutional rights (R. 13). Accompanying this motion,

and tendered, were affidavits showing that members of the

N. A. A. C. P. in nearby counties had been subjected to re

prisals when identified as signers of a school desegregation

petition, and a showing of evidence of hostility to the pur

poses and aims of the organization in Alabama, and evi

dence that groups in the state were organized for the ex

press purpose of ruthlessly suppressing petitioner’s pro

gram and policy (R. 13).

This motion was heard, tender of documents refused

and the motion denied on July 30 (R. 14), and on the same

day a motion to stay was filed in the Supreme Court of

the state (R. 14). This motion was heard on July 31 and

was denied the same day (R. 14). Without waiting for the

Supreme Court to announce its decision, the trial court

on July 31 adjudged petitioner in further contempt and

assessed a fine of $100,000 against it (R. 14-15). Petitioner

filed a petition for writ of certiorari and brief in support

thereof in the Supreme Court of Alabama on August 8,

which petition was denied that same day as insufficient

(91 So. 2d 221). On August 20, 1956, petitioner filed a sec

ond petition for writ of certiorari, which was denied Decem

ber 6, 1956 (R. 23). From this decision petitioner brings

the cause here.

12

The Climate in Alabama

This case cannot be properly considered without being

viewed against the background and setting in which it

arose. Alabama officials in responsible positions have set

the tone and pattern for local governmental officials, civic

leaders, educators, parents, and citizens in voicing bitter

opposition to any change in the state policy and pattern of

racial segregation, regardless of any requirement of the

United States Constitution. The Governor,5 * * 8 Lt. Governor,®

5 Southern School News, March, 1956, Vol. II, No. 9, Gov. James

E. Folsom: “ Anybody with any sense knows that Negro children and

white children are not going to school together in Alabama any time

in the near future . . . in fact, not for a long time.” p. 6, col. 1.

Southern School News, April, 1956, Vol. II, No. 10, Gov. James

E. Folsom campaigning for election as national Democratic com

mitteeman : “ My views are well known on the subject. I was and am

for segregation. That’s all I have to say on the subject.” p. 5, col. 1.

Southern School News, June, 1956, Vol. II, No. 12, Gov. James

E. Folsom: Folsom announced that white and Negro students would

not attend the same grade schools and high schools in Alabama “ as

long as I am Governor.” p. 10, col. 3.

Southern School News, July, 1956, Vol. I ll , No. 1, Gov. James

E. Folsom commenting on Lucy affair: “ There is not going to be

any race-mixing in our public schools as long as I am governor.”

p. 10, col. 5.

8 Southern School Nezvs, December, 1955, Vol. II, No. 6, Lt. Gov.

Guy Hardwick addressing the Alabama Chamber of Commerce stated

that there can be no enforcement of the Supreme Court decision in

Alabama because the public is “ bitterly opposed” to such a change.

He stated that the state legislature had passed a school placement law

and “ it appears they will pass others and additional laws in order to

insure that segregation will remain in our schools.” p. 4, col. 4.

Southern School News, August, 1957, Vol. IV, No. 2, Lt. Gov.

Guy Hardwick: “ [If the civil rights bill passes] all white men will,

of necessity, be drawn together by common bonds of resistance, and

I predict they will refuse to employ, feed, clothe or otherwise aid or

assist Negroes if the latter insist on disrupting and upsetting our way

of life in Alabama . . . We will resort to the greatest and most effec

tive boycott ever seen in Alabama or any other state . . . No man

will be elected governor of Alabama unless he enters into a solemn

pact with the voters . . . to maintain segregation, and further pledges

he will not use the National Guard . . . manning tanks, to escort

Negro children into white schools as was done in Tennessee and

Kentucky.” p. 4, col. 5.

13

state legislators,' the Alabama State Superintendent of

7 Southern School News, June, 1955, Vol. 1, No. 10, Sen. Sam

Engelhardt (Macon County) : As far as I am concerned, abolition of

segregation will never be feasible in Alabama and the South. No brick-

will ever be removed from our segregation walls.” p. 2, col. 2.

Sen. Walter Givhan (Dallas County) : “ I think we have won a

decided victory for the South, it was brought about by the con

stant fight the southern people have put up, bringing to the attention

of the American public that integration wasn’t feasible and never

would have worked, and that the southern people under no condition

would have stood for it.” p. 2, col. 2. Sen. Roland Cooper (W ilcox) :

“ I cannot forsee where desegregation would be feasible or local con

ditions would warrant it within 100 years in Wilcox County.” p. 2,

col. 2. Sen. E. O. Eddins (Marengo County) advocated prompt

action “ to pass every law that would be a safeguard so far as segrega

tion is concerned.” p. 2, col. 2.

Southern School News, August, 1955, Vol. II, No. 2, Sen. Sam

Engelhardt (Macon County) stated to the Alabama Senate Edu

cation Committee “ W e’ve got 190 colored teachers in Macon County

and the board [Macon’s Board of Education] tells me they’ll fire

every one of them that takes part in this agitation.” p. 13, col. 3.

* * * “ The National Association for the Agitation o f Colored People

forgets there are more ways than one to kill a snake . . . we will

have segregation in the public schools of Macon County or there will

be no public schools.” p. 13, col. 5.

Southern School News, January, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 7, Sen. Sam

Engelhardt (Macon County) commenting on The Institute on

Non-Violence in Montgomery, Dec. 3-9, 1956: “ Montgomery is sit

ting on a potential keg of dynamite. If there is violence, and pray

that there won’t be, each of us should buy a towel and send it to the

Supreme Court for them to wipe the blood off their hands

Think white, talk white, buy and hire white.” p. 15, col. 1.

Southern School Ne-ws, April, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 10, Rep. W. L.

Martin (Greene County) : The state appropriation to Tuskegee was

originally made "to prevent the necessity of Negroes attending white

colleges.” Should members of their race insist on enrolling at white

colleges, “ they have no more need for state money.” p. 13, col. 2-3.

Southern School News, June, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 12, Senator

Albert Boutwell (Birmingham): “ I think we will adopt only meas

ures to keep segregation in a legal manner, and that we are going to

do it with a great deal of deliberation. We don’t want to abolish

schools except as a last resort. But we must be ready to do it if

necessary.” p. 12, col. 1-2. Senator Broughton Lamberth (Talla

poosa County) : “ W e’ll do everything possible to keep segregation

in the schools.” p. 13, col. 4.

14

Schools,8 * local officials 0 and even judges,10 have consist

ently issued public declarations that the constitutional

mandate prohibiting racial discrimination in public educa

tion should be resisted, and segregation strengthened. Fol

lowing the May 17, 1954 decision, the state assembly

adopted scores ot resolutions and pieces of legislation,

8 Southern School News, June, 1955, Vol. I, No. 10, State

Superintendent of Education, Austin R. Meadows commenting on

the May 31, 1955 U. S. Supreme Court decision: “ I believe that the

overwhelming majority of Negroes realize that segregation is what the

people in Alabama want, and I believe they are friendly enough to

cooperate with the majority who want segregation.” p. 2, col. 2.

Southern School News, May, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 11, State Super

intendent of Education, Dr. Austin R. Meadows, suggested that

segregation might be maintained by “our white people influencing

the Negroes to go to their own schools.” p. 5, col. 2.

0 Southern School News, Sept., 1955, Vol. II, No. 3, Board of

Education of Mobile in a formal statement of policy refusing to end

segregation: “ . . . the tradition of two centuries can be altered by

degrees only.” p. 3, col. 4.

Southern School News, February, 1956, Vol. II, No. 8, L. R.

Grimes, Chairman of the Montgomery County Board of Revenue

announcing his membership in the White Citizens Council: “ I think

every right-thinking white person in Montgomery and the South

should do the same. We must make certain that Negroes are not

allowed to force their demands on us . . . ” p. 6, col. 5.

Southern School News, December, 1956, Vol. I l l , No. 6, Mayor

W. A. Gayle of Montgomery commenting on the bus decision: “ Like

thousands of our Montgomery citizens, the city commission

deplores the . . . decision . . . at the same time we ask our fellow

citizens to remain calm and coolheaded, while your commissioners

work diligently and earnestly to do all legal things necessary to con

tinue enforcement of our segregation laws and ordinances of all

kinds . . . enacted in recognition of long-established customs, morals

and habits of our people . . . We shall continue to enforce segrega

tion.” p. 13, col. 3.

Southern School News, January, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 7, the Mont

gomery City Commission commenting on the Supreme Court decision

ending segregation on Montgomery buses: “ Although we consider

the Supreme Court’s decision to be the usurpation of the power to

10 Text of this footnote appears on page 15.

15

ranging from a “ nullification” resolution to pupil place

ment laws, intended to maintain racial segregation and

defy federal authority.11 Threatened and actual loss of

amend the Constitution . . . we have no alternative but to recognize

it. That is not to say, however, that we will not continue, through

every legal means at our disposal, to see that the separation of races

is continued on the public transportation system here in Montgomery

. . . The City Commission . . . will not yield one inch, but will do

all in its power to oppose the integration of the Negro race with the

white race in Montgomery and will forever stand like a rock against

social equality, intermarriage, and mixing of the schools . . . There

must continue the separation of the races under God’s creation and

plan.” p. 15, col. 1-2.

Southern School News, March, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 9, a Mont

gomery grand jury returning indictments against four white men on

dynamiting charges: The return of the indictments “ should not be

construed as any weakening of the determination of the people of

Montgomery to preserve our segregated institutions. We reaffirm

our belief in complete segregation. We are determined to maintain

it and to maintain law and order as it applies both to those who sup

port segregation and to those who oppose it.” p. 12, col. 4.

10 Southern School News, May, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 11, on

April 8, Circuit Judge James A. Hare said: “ . . . despite federal

rulings, segregation matters will be handled at the local level.” In

charging a Dallas County grand jury, the Black Belt judge said he

would “ advise our colored friends who follow the false hopes of

integration to go where their hopes lead them." “ Since the Supreme

Court decision of 1954” , Hare said, “ more segregation laws have been

passed than in the previous 150 years.” p. 5, col. 2. The trial judge

in the instant proceedings has been especially outspoken in his sup

port for racial segregation and condemnation o f petitioner (see infra

at p. 40).

11 Nullification Resolution : Acts of Ala. Spec. Sess. 1956, Act 42,

at 70. Resolution petitioning Congress to limit the jurisdiction of the

U. S. Supreme Court and other federal courts on appeals from state

courts: Southern School Neivs, Vol. I, No. 7, p. 3. Report of a

special legislative committee calling for a private school plan and a

threat of economic reprisals: Southern School News, Vol. 1, No. 3,

p. 2. In the following issues of Southern School News there are

reports of resolutions and legislation defying the Constitution of the

United States: Vol. IV, No. 1, July, 1957; Vol. I ll , Nos. 1-12,

July, 1956-June, 1957; Vol. II, Nos. 1-12, July, 1955-June, 1956;

Vol. I, Nos. 1-10, Sept., 1954-June, 1955. “ Status of School Segre

gation-Desegregation in the Southern and Border States.” Southern

Education Reporting Service, April 15, 1957, p. 3.

16

employment and other forms of economic reprisals have

accompanied legislation intended to punish financially those

persons who advocate ordery compliance with the law as

well as those who advocate equal rights for all. Violence

and bloodshed have been predicted by high state officials

if segregation is ended. Threats and actual acts of violence

have been directed against Negroes who seek to assist their

constitutional rights 12 as well as against whites who seek

compliance with the law.13 While Negroes have been

12 Year-long series of bombings and shootings of Negro leaders in

bus segregation issue. Southern School News, Feb., 1957, Vol. I ll ,

No. 8, p. 15.

In Montgomery, 19 major acts of violence— 9 bombings and 10

shootings— were directed against buses, or the homes of Negro

leaders. Southern School Notes, March, 1957, Vol. I l l , No. 9, p. 12.

In Montgomery, Dec., 1956, one Negro woman was hit in both

legs by bullet during firing on buses. Southern School News, Jan.,

1957, Vol. I ll , No. 7, p. 14.

In Birmingham, the home of Rev. F. L. Shuttlesworth, a Negro

leader of the bus boycott, was bombed. Southern School News, Jan.,

1957, Vol. I ll , No. 7, p. 14.

In Montgomery, four Negro churches were bombed. Also the

homes of two ministers, both leaders in bus boycott, one leader white

and one Negro. A Negro cab stand was blasted. An attempt was

made to bomb home o f Rev. M. L. King. Southern School News,

Feb., 1957, Vol. I l l , No. 8, p. 15.

Ku Klux Klan activity, demonstrations, and cross burnings, were

reported in Opelika, Montgomery, Mobile, Birmingham, Prattville

and other Alabama communities. Southern School News, Jan. 1957,

Vol. I ll , No. 7, p. 15; Feb., 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 8, p. 15; March, 1957,

Vol. I ll , No. 9, p. 13; June, 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 12, p. 13; Dec.,

1956, Vol. I ll , No. 6, p. 13.

In Birmingham, Rev. F. L. Shuttlesworth was physically attacked

when he attempted to enroll Negro students in an all-white school.

N. Y. Times, Sept., 10, 1957, p. 1, col. 3.

In Birmingham, two false bombing reports at Phillips High

School and student demonstrations at Woodland High School fol

lowed reports that Negro students would attempt to enroll at these

schools. N. V. Times, Sept. 11, 1957, p. 23, col. 3.

13 In Birmingham, a white steel worker (Lamar Weaver) was

attacked on March 6, 1957 by a crowd of white men after he sat

beside a Negro couple in a Birmingham railroad station. Weaver, who

17

refused official protection from threats of physical violence,

where Negroes have protested against deprivation of their

rights, state officials have been quick to curb this “ lawless”

activity.14 Other pressures have been exerted on Negroes

to maintain “ voluntary” segregation. Alabama officials

have committed themselves to a course of persecution and

intimidation of all who seek to implement desegregation.

Negroes who seek to secure their constitutional rights do

so at the peril of intimidation, vilification, economic re

prisals, and physical harm.

It is in this climate that the instant proceedings took

place. In view of petitioner’s seeking the elimination of

racial segregation and other barriers of race, its attempted

suppression by state authorities was all but inevitable.

With whatever cloak of legality respondent may seek to

invest these proceedings, the due process accorded peti

tioner should be viewed against a background of open

opposition by state officials and an atmosphere of violent

hostility to petitioner and its members. It is only in this

context that these proceedings can he properly measured

to test their fundamental validity. So viewed and consid

ered, the unconstitutionality and illegality of these pro

ceedings will be unmistakably revealed.

has made pro-integration speeches, escaped in his car in a storm of

heavy stones. He was struck in the face with a suitcase, windows of

the car were shattered. Southern School News, April, 1957, Vol. I ll ,

No. 10, p. 13.

The home of a white minister was bombed. Southern School

News, Feb., 1957, Vol. I ll , No. 8, p. 13.

14 Southern School News, August, 1957, Vol. IV, No. 2, Att. Gen.

John Patterson, in a statement issued after raids on the Tuskegee Civic

Association and a Tuskegee print shop: “ [The investigation] was

undertaken due to the illegal operations of the TCA, due to the racial

trouble and strife the organization is stirring up in Macon County

and due to certain individuals connected with the said organization

who have connections with foreign organizations whose purposes and

aims are not in the best interests of the welfare of this state. Such a

boycott as is being carried out by the TCA is in violation of the laws

of this state and cannot be tolerated. Certain foreign organizations

that are bent upon stirring up racial strife and disorder in our state

have been instrumental in bringing about this illegal boycott.” p. 4,

col. 4.

18

Summary of Argument

Petitioner has been adjudged in contempt, fined $100,000

and ousted from Alabama— solely because petitioner and

its members seek to obtain for Negro Americans “ what

they think is due them” under our system of government.

United States v. Harriss, 347 U. S. 612, 633, 635 (Justice

Jackson dissenting).

Petitioner is a voluntary association whose primary

objective, as its name implies, is improvement of the status

of colored people in the United States. It was organized

in 1909 and incorporated under the laws of the State of

New York as a membership, non-profit corporation in 1911.

Today petitioner is a national organization and has affili

ated local units in Alaska and the 48 states. Petitioner

does not advocate violence to further its aims; it espouses

no subversive or alien ideology; it fosters no social or

political reforms adverse to the interests of the United

States. On the contrary, it seeks to nourish faith in the

perdurance of our democratic institutions.

Petitioner is a political organization, and in seeking to

improve the Negro’s status through democratic processes,

petitioner and its members are exercising rights of free

association and free speech basic to our society.

Prom the rationale distilled from the decisions of this

Court, petitioner and its members have the protection of

the Fourteenth Amendment to pursue these activities free

from state encroachment. See e.g., United States v. Rum-

ley, 345 U. S. 41; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353; Thomas

v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S.

183, 194, 195; Terrniniello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ; Sweezy

v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234. Cf. Burstyn v. Wilson,

343 U. S. 495; Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178.

Petitioner asserts here its own right to freedom of

association and free speech, as well as that of its members

and contributors. See Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra,

19

at 250, 251; Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v.

McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 149, 183. Since loss of member

ships and contributions are also involved, it claims prop

erty rights as well. See Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268

U. S. 510.

Alabama alleges in these proceedings the right to re

strain all activities of petitioner and its members and the

right to punish petitioner in contempt for refusing to sub

mit to state interference with its right of free speech and

association. The justification for restraint of petitioner’s

activities was that it had failed to qualify to do business in

the state in accordance with state law and that injunctive

relief was essential to protect the state’s welfare (R. 2).

Even conceding this to be a bona fide state interest does not

dispose of the issues which these proceedings raise. Peti

tioner and its members seek to implement in Alabama

rights secured by the federal Constitution, and a state

cannot bar such activity altogether on the pretext of secur

ing compliance with state law. Cf. Hill v. Florida, 325

U. S. 538; Garner v. Teamsters C. & H. Union, 346 U. S.

485, 500; Thomas v. Collins, supra; and see Theard v.

United States, 354 U. S. 278. That the state’s real aim

is not petitioner’s registration with the Secretary of State,

but petitioner’s ouster, is crystal clear. Moreover, there

is nothing in the state’s bill of complaint or in the record

to justify the circuit court in issuing its injunctive decree

without first according petitioner an opportunity to be

heard.

The interlocutory order requiring petitioner to disclose

to the state the names and addresses of its members, dis

obedience of which gave rise to petitioner’s contempt cita

tion, was an unwarranted and arbitrary invasion of an

area of personal freedom immune from inquisition by

political authorities. See Watkins v. United States, supra;

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra; United States v. Rumley,

supra, at 57; National Labor Relations Board v. Essex

2 0

Wire Co., 245 F. 2d 589 (9th Cir. 1957); National Labor

Relations Board v. National Plastics Products Co., 175

F. 2d 755, 760 (4th Cir. 1949).

Moreover, the order of the trial court requiring dis

closure of petitioner’s members, granted ostensibly to aid

the state in its preparation for a trial on the merits, was

entered before it could have been determined that such pro

ceedings would ever be necessary.

The truth is that Alabama seeks, in these proceedings,

to silence petitioner and its members. Its purpose is to

eradicate effective opposition to continued governmental

maintenance of racial segregation by insulating the state’s

unconstitutional policy against the reach of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Obviously mere state opposition to peti

tioner ’s aims and purposes cannot vindicate the state power

here asserted, for the reason free speech is constitutionally

guaranteed is to preserve the freedom of those in dissent,

no matter how weak and unpopular, under the circum

stances and conditions now prevalent in Alabama.

The contempt citation and the punishment imposed

therefor were vindicative and arbitrary, as indeed were the

entire proceedings. Petitioner is subjected to heavy pen

alties for seeking to protect its constitutional rights. Peti

tioner’s action in this cause poses no threat to the admin

istration of justice in Alabama, and these proceedings pre

sent no valid issue of that nature. Here the state used its

judicial machinery to try to convict petitioner for the

ideas it espouses and lawfully seeks to implement. The

state’s aim was to ban petitioner’s activities by the pre

tense of a judicial procedure, and that is the vice of these

proceedings. There was lacking a fair and impartial hear

ing as required by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The judgment below therefore cannot be

sustained.

21

ARGUMENT

I .

The Fourteenth Amendment Prohibits the State

From Interfering With the Activities of Petitioner.

Petitioner and its members seek the “ economic, politi

cal, civic and social betterment of colored people and their

harmonious cooperation with other peoples” 16 in Alabama

and throughout the United States. In seeking to attain

these objectives through the petitioner organization, indi

vidual members are exercising the right of free association

for their mutual protection and for the more effective ad

vancement of group interests—a right fundamental to our

society. See National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and

Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U. S. 1, 33.

In advocating and seeking the betterment of the Negro’s

status in America petitioner and its members are merely

invoking their constitutionally protected rights of free

speech and free association guaranteed under the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. See Pierce

v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510; Sweezy v. New Hamp

shire, 354 U. S. 234; Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297

U. S. 233; Times-Mirror Co. v. Superior Court, 314 U. S.

252; Pennekamp & Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Florida,

328 U. S. 331; National Broadcasting Co., Inc. v. United

States, 319 U. S. 190; Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495;

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 253; Joint Anti-Fascist

Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 149, 183

(concurring opinions).

Solution of the American race problem—one of the

great social issues of this era—is the cause to which peti

tioner and its members are devoting their efforts and

energy. The right to free discussion of the problems of 15

15 This is quoted from Article 2, Constitution and By-laws of

Branches of NAACP, March, 1956.

22

our society and to engage in lawful activities aimed at

their alleviation is one of the unique and indispensable

requisites of our system. See Pennekamp v. Florida, supra,

at 346; Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 327; Stromberg

v. California, 283 U. S. 359, 369. The fact that some may

view the ideas petitioner and its members espouse as ill-

advised or even infamous is of no moment. For the right of

freedom of association and free speech is accorded to

dissident and unpopular minorities, as well as those advo

cating ideas or engaging in activities of which those in

power approve. See Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88;

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268; Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, supra; Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organiza

tion, 307 U. S. 496; Sweezy v. Hew Hampshire, supra;

cf. Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178. The unimpaired

maintenance of freedom of association and free speech is

considered essential to our political integrity, see Whitney

v. California (Justice Brandeis concurring), 274 U. S. 357,

376; Stromberg v. California, supra; and their safeguard

in our basic law postulates a belief in the fundamental good

sense of the American people.10 In sum, petitioner and its

members are exercising fundamental rights and engaging

in activities basic to a free society.

It is clear that an individual who merely seeks vindi

cation of his constitutional rights or improvement of his

economic, social and political status by lawful means can- 16

16 Justice Holmes’ opinion in Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S.

616 at 630 is an expression of this idea: “ But when men have realized

that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe

. . . that the ultimate good desired is better reached by a free trade

in ideas.” It was undoubtedly belief in the vital importance, both

political and nonpolitical, of free speech which led this Court after

some hesitation to construe the Fourteenth Amendment as incor

porating against the states the First Amendment’s proscription. Com

pare Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U. S. 454; Gilbert v. Minnesota,

254 U. S. 325; Prudential Insurance Co. v. Cheek, 259 U. S. 530

with Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 and Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359.

23

not be held guilty of illegal conduct. And the fact that

such activity is taken in concert, of course, does not render

it illegal. See International Union v. Wisconsin Employ

ment Relations Board, 336 U. S. 245, 258.

While petitioner eschews partisan politics, it seeks to

influence public opinion and affect the political structure

to achieve its objectives. As such it is a political organiza

tion in the true sense, with its activities outside the area

of state interference absent compelling justification.17 See

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41; Watkins v. United

States, supra at 250-251; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S.

148, 196; Sweezy v. Neiv Hampshire, supra, at 265, 266.

In Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra, at 250, 251, Mr.

Chief Justice Warren said:

Equally manifest as a fundamental principle of

a democratic society is political freedom of the indi

vidual. Our form of government is built on the

premise that every citizen shall have the right to

engage in political expression and association. This

right was enshrined in the First Amendment of the

Bill of Rights. Exercise of these basic freedoms in

America has traditionally been through the media

of political associations. Any interference with the

freedom of a party is simultaneously an interference

with the freedom of its adherents. All political ideas

cannot and should not be channeled into the pro

grams of our two major parties. History has amply

proved the virtue of political activity by minority,

dissident groups, who innumerable times have been

in the vanguard of political thought and whose pro

grams were ultimately accepted. Mere unorthodoxy

or dissent from the prevailing mores is not to be con

demned. The absence of such voices would be a

symptom of grave illness in our society.

17 Petitioner also aids Negroes in vindicating their constitutional

rights of freedom from discrimination in courts. In so far as these

activities involve the federal courts, there is a further serious question

of state jurisdiction to prohibit or interfere in any way. See Theard

v. United States, 354 U. S. 278.

24

Mr. Justice Frankfurter in Wieman v. Updegraff, supra,

characterized membership in a club of a political party as

“ a right of association peculiarly characteristic of our

people,” and joining such an organization as an exercise

of rights of free speech and free inquiry. More recently

in Sweezy v. New Hampshire, supra, Mr. Justice Frank

furter has given expression to the fundamental nature of

activities in political organizations. There he said at page

266 that in the political and academic realm, “ thought and

action are presumptively immune from inquisition by the

political authority.” And at another point in the same

opinion (265), Mr. Justice Frankfurter stated:

The inviolability of privacy belonging to a citi

zen’s political loyalties have so overwhelming an

importance to the well being of our kind of society

that it cannot be constitutionally encroached upon

on the basis of so meager a countervailing interest of

the State as may be argumentatively found in the

remote, shadowy threat to the security of New Hamp

shire allegedly presented in the origins and con

tributing elements of the Progressive Party and in

petitioner’s relations to these.

That group activity plays a vital role in the enactment of

legislation, conduct of party activity, formulation and exe

cution of public policy in public administration and the pro

tection of civil liberties is no longer open to question. See

Latham, “ The Group Basis of Politics,” (1950) passim.

Indeed, petitioner and organizations of its character at

times bridge the academic and political fields, for they often

seek to concretize the academician’s social and economic

abstractions into governmental action through their influ

ence upon political parties and office holders. It is sub

mitted, therefore, that these aforementioned principles are

particularly apposite here, and that their application neces

sarily renders these proceedings invalid.

It should be noted that petitioner solicits membership

dues and financial contributions to aid in carrying on these

25

activities. That alone, however, cannot place petitioner’s

activities outside the protection which the Fourteenth

Amendment affords. Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S.

105; Follett v. McCormick, 321 IT. S. 573; Burstyn v.

Wilson, supra.

While some nondiscriminatory regulation of petitioner’s

activities might be permissible, a blanket prohibition is be

yond the state’s power. See Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S.

516; Burstyn v. Wilson, supra; International Brotherhood

of Teamsters v. Vogt. Inc., 354 U. S. 284. The restraining

order entered in this cause constitutes such a forbidden

regulation which cannot be sustained.

Nor can a blanket restraint be justified on the ground

that petitioner’s activities are at variance with some legiti

mate state policy. Of. Hughes v. Superior Court, 339 U. S.

460. For such a proscription as here imposed would seem

to constitute a prior restraint upon the exercise of rights

of free speech and association forbidden by the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697; Kings

ley Books v. Brown, 354 U. S. 436, 445; Roth v. United

States, 354 U. S. 476, 496, 497.

The sole legal basis urged for the state’s interference

with petitioner’s activities was its failure to register with

the Secretary of State as a foreign corporation doing busi

ness in Alabama. See Title 10, Sections 192, 193, 194, Code

of Alabama, 1940. There can he no doubt that the state can

not upon this pretext justify interference with free speech

and freedom of association. A mere semblance of a state

interest is not sufficient to justify invasion of the rights of

free association and free speech. See United States v.

Rumely, supra; Watkins v. United States, supra, at 198.

And, it is submitted, the state cannot interpose its policy

or procedure for the purpose of defeating or infringing con

stitutionally secured federal rights. See Hill v. Florida,

325 U. S. 538; Garner v. Teamster C. H. Union, 346 U. S.

485, 500. Restriction upon exercise of petitioner’s consti

26

tutionally protected right to advocate and seek by lawful

means equal rights for Negro Americans, therefore, cannot

be justified on the ground that compliance with state regis

tration statutes was being sought, particularly in light of