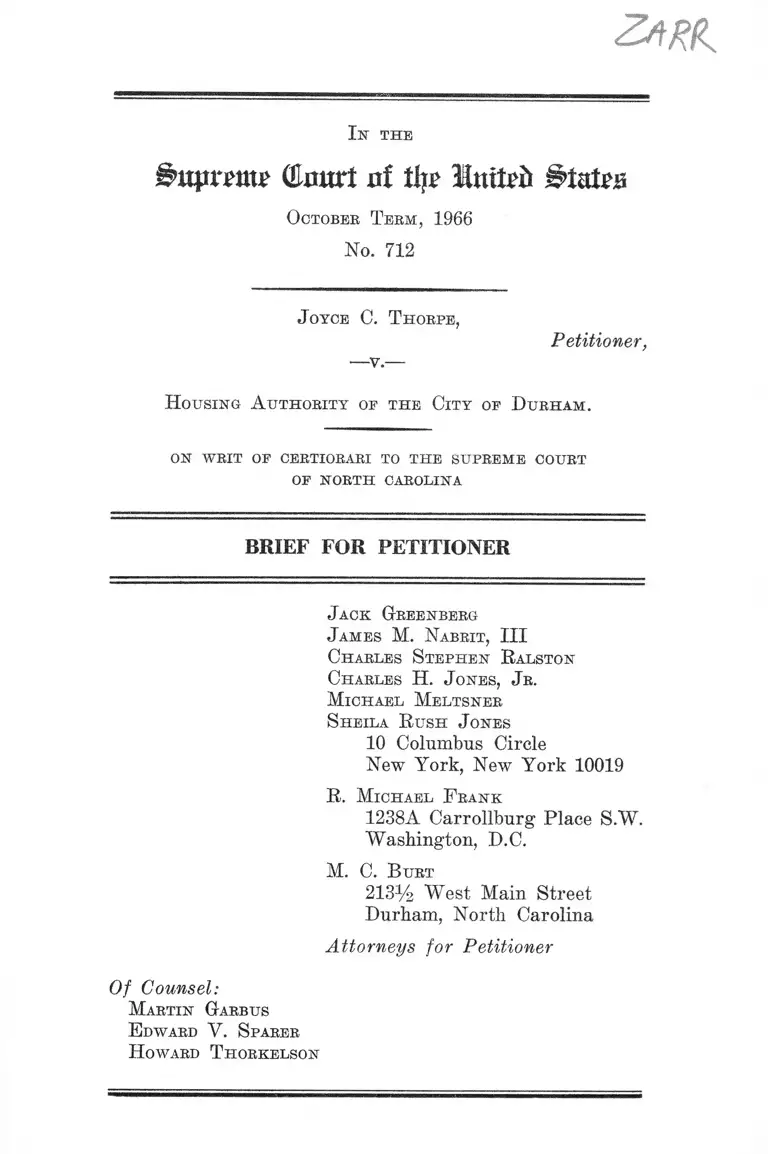

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham Brief for Petitioner, 1966. bb2d5629-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ae780084-b1cd-420d-a3bf-c0c50d34bfc6/thorpe-v-housing-authority-of-the-city-of-durham-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

Z * R k

Isr th e

(Umtrt at tip Im M §>tato

O ctober T er m , 1966

No. 712

J oyce C. T horpe ,

H ousing A u th o rity oe th e Cit y op D u rh a m .

Petitioner,

on w r it op certiorari to th e suprem e court

OP NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

J ack Greenberg

J ames M . N abrit , TIT

Charles S teph en R alston

C harles H . J ones, J r .

M ich ael M eltsner

S h e ila R u sh J ones

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

R . M ic h ael F r an k

1238A Carrollburg Place S.W.

Washington, D.C.

M . C. B urt

213% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

Attorneys for Petitioner

Of Counsel:

M artin G arbus

E dward Y. S parer

H oward T horkelson

I N D E X

Opinions Below ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 1

PAGE

Question Presented ......................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 2

Statement ........................-................................................. 3

Summary of Argument 9

A rg u m en t :

Petitioner Was Denied Due Process of Law by

Her Eviction}from a State and Federally Sup

ported Low-Income Housing Project, w-t -'t+ru A+r-

pf fhr B^nr^n H r the Frir-Dnn nr any TToarinopta.

Cjffl±astAbA-S«6ia^aB™tiieA*eaiW«neiBtaj-Aetiun .... 12

Introduction 12

I. Public Housing Agencies May Not Evict

Tenants Arbitrarily......................................... 14

II. Petitioner Was Entitled'^Notice^f the Rea

son He¥i«w-fee©*aeHirrc^I^S^re#te“W'ere

Cancelled.. B ^ -.ii£ fi,fy icT!9d......................... 23

III. Petitioner Was Entitled to an Administra-

t i ^ *ffearinĝ )to Contest the C^ncelMicin^of

.. 40C onclusion

A ppendix—

i i

Excerpts from the United States Housing Act of

PAGE

1937 (42 U.S.C. §1401 et seq.) ............ ............... la

Excerpts from the North Carolina “Housing Au

thorities Law” (Gen. Stats, of North Carolina,

§157-1 et seq.) ............. ............... ........ ........... ..... .... 10a

North Carolina Statutes Re Summary Ejectment

(Gen. Stats, of North Carolina, §42-46 et seq.) .... 23a

T able oe Cases

Banks v. Housing Authority of City and County of

San Francisco, 120 Cal. App. 2d 1, 260 P.2d 668

(1953), cert, denied, 347 U.S. 974 (1954) __________ 20

Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26 _________________ 10, 26, 37

Bi-Metallic Inv. Co. v. State Board of Equalization,

239 U.S. 441............. ............................ ......................... 34

Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 I11.2d 319,

122 N.E.2d 522 (1954) .................... ............................ 15

Chin Tow v. United States, 208 U.S. 8 ......................... 34

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363 ....11, 32

Coe v. Armour Fertilizer Works, 237 U.S. 413 ............... 33

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278

(1961) _____________________ ____ _______ ________ 21

Detroit Blousing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F.2d 180

(6th Cir. 1955) ................................ ............................. 20

Dixon v. Alabama State B<j. of Ed., 294 F.2d 150

(5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 930 .........11, 30, 34

Frost Trucking Co. v. Railroad Commission, 271 U.S.

583 ........................ .............................. ...................... ..10,29

Gonzales v. United States, 348 U.S. 407

Greene v. McElroy, 360 U.S. 474 .........

,..,,,24, 27

34-35, 39

I l l

Hanover Fire Insurance Co. v. Carr, 272 U.S. 494 .... 30

Holt v. Richmond Dedevelopment and Housing Au

thority, Civil Action No. 4746, E.I). Va., Sept. 7,

1966 .................. ....................... .... ........ ............15, 27, 28, 39

Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cordova, 130

Cal. App.2d 883, 279 P.2d 215 (App. Dept. Super.

Ct. 1955) ......... ................ ............................. ................ 15

I.C.C. v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 227 U.S. 88 ........... . . . 11, 34

Japanese Immigrant Case (Tamataya v. Fisher), 189

U.S. 86 ___ __________ ______________ ________ .....11,34

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 ..................................... 30

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341

U.S. 123 ..... ...................... ..... ....... .................. ..11, 25, 36-39

Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp 123 (E.D.

Mich. 1954) ________ ___ ________ _____ _____ _____ „. 20

PAGE

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp.

174 (M.D. Tenn. 1961) ......................................... ....... 34

Kutcher v. Housing Authority of Newark, 20 N.J. 181,

119 A.2d 1 (1955) ............................. ........... ............ 15

Kwong Hai Chew v. Golding, 344 U.S. 590 .................... 34

Lawson v. Housing Authority of City of Milwaukee,

270 Wise. 269, 70 N.W.2d 605 (1955), cert, denied,

350 U.S. 882 (1955) ......................................... . 15

Londoner v. Denver, 210 U.S. 373 .................... ........11, 34

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 ..................10, 11, 24,

25, 27, 34

Morgan v. United States, 298 U.S. 468 ......................... 34

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 ................................... . 22

Ng Fung Ho v. White, 259 U.S. 276 ............................. 37

IV

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Com., 301

PAGE

U.S. 292 _______________ _____________________ _ 14

Be Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 .................................................... 33

Powell v. Eastern Carolina Regional Housing Auth.,

251 N.C. 812, 112 S.E.2d 396 (1960) .............. ........... 19

Rudder v. United States, 226 F.2d 51 (D.C. Cir. 1955)

14-15, 23

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 ................. ..... .............. 30

Sherbert v. Yerner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) ...........10,11,14, 21,

29, 39, 40

Simmons v. United States, 348 U.S. 397 ____________ 27

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350 U.S.

551 ______ ____ __________ ____ ________ __11,14,30,34

Southern R. Co. v. Virginia, 290 U.S. 190 ........... .......11, 34

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 __________ 10,11, 21, 29, 40

Steier v. New York State Educ. Com’r, 271 F.2d 13

(2d Cir. 1959), cert, denied, 361 U.S. 966 ............... . 34

Swan v. Board of Higher Education, 319 F.2d 56 (2nd

Cir. 1963) ............. ...... .... ............................................. 34

Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super. 116, 103 A.2d 632

(1954) ......... ............... ................................................... 20

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 __ _________ ___ .21, 30

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U.S. 517 ............. ...... ..... 10, 22, 23, 40

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 .......... 30

United States v. Allegheny County, 322 U.S. 174 ...... 32

United States v. Helz, 314 F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1963) .... 32

United States v. Yazell, 382 U.S. 341.......... ......... ......... 32

Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, 113

F. Supp. 210 (N,D. Ohio, 1953) ............... ................. 2 0

V

Wheeling’ Steel Corp. v. Glander, 337 U.S. 562 .......... 30

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 __ _________21, 22, 30

Williams v. City of Ypsilanti, C.A. No. 28936, D. Midi.,

1966 .............................. ................................................. 15

Willrier v. Committee on Character & Fitness, 373

U.S. 96 ................................................... ........ ..10,11,23,34

Wong Yang Snng v. McGrath, 339 U.S. 33 .................. 34

Woods v. Wright, 334 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1964) .......... 34

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 .............................. . 14

PAGE

S tatutes and R egulations

28 U.S.C. § 1257 (3) .................. ....................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 1401 ...................... ...................... ..2,15,18, 25, 32

42 U.S.C. § 1402 .............................. ........ ........................ 2

42 U.S.C. § 1404a ................ ....... .................... ........ ...2,16,17

42 U.S.C. § 1410 (g) (3) ....................................................3,16

42 U.S.C. § 1415 (7) ................. ......................... ............3,18

Act of July 31, 1947, c, 418, § 2, 61 Stat. 705 (formerly

42 U.S.C. § 1413a) .......... ............................................ 17

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000(1......... ............................. ............................... . 20

24 C.F.R., Subtitle A, Part 1 __ ___________ _________ 20

Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg. 11527 (1962) 20

Housing and Rent Act of 1947, Title II, §209 (b),

61 Stat. 201 ............... ..... .............................. ............- 17

Housing Act of 1948, Title V, § 502 (b), 62 Stat. 1284 17

VI

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-26 ....................... ........................ 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-28 ....... 3; g

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-29 ______ 3, 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-30 ...... 3, 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-31 _____ 3; 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-32 ............ 3? 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 42-34 ..... 3) 6

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-1 _________________ ______ 3, 4,15

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-2 ................. ................3,18,19, 25, 26

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-4 __________________ _________ 3; ig

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-9 ......... ................................3, 4,12, 38

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-23 ....... 3

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-29 ...... ...... .................... ...............3,16

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-40 ............ 18

Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-48 ....... 18

93 Cong. Rec. 6044 .......... ..... ................. ..................... 17

93 Cong. Rec. 9867 ____ __ _____ ______ ____ _________ 17

Other Authorities

1 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, § 7.04 (1958) .... 34

Remarks of President Lyndon B. Johnson at Howard

University, Wash., D.C., June 4, 1965, To Fulfill

These Rights, p. 4 _________ _____ __________ _____ 37

Jones, The Rule of Law and the Welfare State,

58 Colum. L. Rev. 143 (1958) .......... .......................... 35

PAGE

V l l

PAGE

Millspaugh, Problems and Opportunities of Relocation,

26 L aw & Co n te m p . P rob. 6 (1961) _________ ____ 19

O’Neil, Unconstitutional Conditions: Welfare Benefits

with Strings Attached, 54 C a lif . L. Rev. 443 (1966) 30

Reich, Individual Rights and Social Welfare: The

Emerging Legal Issues, 74 Y ale L. J. 1245 (1965) .. 19,

35-36

Schorr, S lu m s and S ocial I n secu rity (Dept, o f H.E.W.

Research Report No. 1) (U.S. Govt. Printing Office,

Washington, D.C., 1963) ................ .................. ......... 19

Sternlieb, T en em en t L andlord, Rutgers Univ. Press

(1965) _______ __________________ ________________ 19

I n the

fttp ra tt? (fcmrt at % Htnxtth MuUa

O ctober T eem , 1966

No. 712

J oyce C. T horpe ,

■— v .

Petitioner,

H ousing A u th o rity oe th e Cit y oe D u r h a m .

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF NORTH CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

(R. 26-29) is reported at 267 N.C. 431, 148 S.E.2d 290

(1966). The judgment, including findings of fact and con

clusions of law, of the Superior Court of Durham County

(R. 19-23) is unreported.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of North Carolina

was entered May 25, 1966 (R. 30). On August 12, 1966,

the time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari was

extended by Mr. Justice Brennan to and including Oc

tober 21, 1966 (R. 31). The petition filed October 21, 1966,

was granted December 5, 1966 (R. 32). Jurisdiction of

this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. § 1257(3), petitioner having

2

asserted below and here the deprivation of rights secured

by the Constitution and statutes of the United States.

Question Presented

Petitioner and her children have been tenants in a low-

income housing project constructed with federal and state

funds and administered by the Housing Authority of the

City of Durham, an agency of the State of North Caro

lina, pursuant to federal and state laws and regulations.

The day after petitioner was elected president of a tenants’

organization in the project, the Housing Authority gave

notice that it was cancelling her lease. Petitioner requested

that the Housing Authority tell her the reasons for her

eviction and give her a hearing. The Housing Authority

refused to give her a reason or a hearing but initiated this

summary ejectment action in a state court and obtained an

order that petitioner be removed from the premises.

Under these circumstances, was petitioner denied rights

granted by the due process clauses of the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United

States'?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the First, Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the United States Housing Act,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1401 et seq. The following por

tions of the Housing Act are set forth in the Appendix,

infra, pp. la to 9a:

42 U.S.C. § 1401

42 U.S.C. § 1402

42 U.S.C. § 1404a

3

42 IJ.S.C. § 1410(g)

42 IJ.S.C. §1415(7)

This case also involves the North Carolina “Housing

Authorities Law” , Gen. Stats, of North Carolina, § 157-1

et seq. The following portions of the “Housing Authorities

Law” are set forth in the Appendix, infra, pp. 10a to

22a:

N.C.G.S. §157-2

N.C.G.S. §157-4

N.C.G.S. §157-9

N.C.G.S. §157-23

N.C.G.S. §157-29

The case also involves North Carolina statutes relating

to summary ejectment proceedings, Gen. Stats, of North

Carolina, § 42-26 et seq. The following sections are set

forth in the Appendix, infra, pp. 23a to 27a:

N.C.G.S. §42-26

N.C.G.S. §42-28

N.C.G.S. §42-29

N.C.G.S. §42-30

N.C.G.S. §42-31

N.C.G.S. §42-32

N.C.G.S. §42-34

Statement

On November 11, 1964, petitioner and her children be

came tenants in McDougald Terrace, a low-rent public

housing project owned and operated by the Housing Au

thority of the City of Durham, North Carolina. The lease

agreement under which petitioner has occupied the project

had an initial term from November 11 to November 30,

1964 (R. 11). The lease further provided that it would

4

thereafter be automatically renewed for successive terms

of one month at a rental of $29 per month, provided there

was no change in her income or family composition or

violation of the terms of the lease (R. 12).

The Housing Authority of the City of Durham was

established under North Carolina law and is “a public

body and a body corporate and politic, exercising public

powers,” Gen. Stat. of N.C. § 157-9. The Authority has

“all the powers necessary or convenient to carry out and

effectuate the purposes and provisions” of the North Caro

lina Housing Authority law (§§ 157-1 et seq., Gen. Stat.

of N.C.), including the powers “to manage as agent of

any city or municipality . . . any housing project con

structed or owned by such city” and “to act as agent for

the federal government in connection with the acquisition,

construction, operation and/or management of a housing

project,” Gen. Stat. of N.C. § 157-9. The Housing Author

ity operates McDougald Terrace as a low rent housing

project “under its statutory authority and pursuant to its

contract with the Federal government” (R. 5).

On August 10, 1965, petitioner was elected president of

the Parents’ Club, a group composed of tenants of the

McDougald Terrace project (R. 6). The following day,

August 11, 1965, the Housing Authority, through its ex

ecutive director, delivered a notice that petitioner’s lease

would be cancelled effective August 31, 1965, at which

time she would have to vacate the premises (R. 5-6);

petitioner received this notice on August 12, 1965 (R. 6).

In the notification the Authority gave no reasons for its

action but merely mentioned a provision of the lease that

it claimed permitted the landlord to cancel upon fifteen

days notice (R. 18).1 After she received the notice, peti

1 The text o f the notice, dated August 11, 1965, is as follows:

Your Dwelling Lease provides that the lease may he cancelled upon

fifteen (15) days written notice. This is to notify you that your

5

tioner, through her attorneys, by phone and by letter re

quested a hearing to determine the reasons for her evic

tion; the request was denied (R. 9). It was stipulated

that “although the Housing Authority had a meeting on

the subject the defendant was not given a hearing in

which she herself was present and reasons assigned to

her” (R. 6). Her attorney met with the Housing Authority

and its executive director on September 1, 1965, and the

attorney again asked for a hearing but the request was

denied (R. 9). Petitioner averred, on information and

belief, that on September 1, 1965, the Housing Authority

held a meeting with a police officer who supplied informa

tion allegedly obtained in an investigation of petitioner

(R. 9). However, neither petitioner nor her attorney were

present at this meeting, and she was not confronted with

her accuser, informed of the information supplied to the

Housing Authority, or given any opportunity to rebut

any charges made against her (R. 9).

In evicting petitioner without giving a reason or a hear

ing, the Housing Authority relied on a sentence in the

lease which provides that: “The Management may termi

nate this lease by giving to the Tenant notice in writing

of such termination fifteen (15) days prior to the last day

of the term” (R. 12). The lease, prepared by the Housing-

Authority, also contained a variety of other provisions for

termination. One provision states that the lease “ shall

be automatically terminated at the option of the manage

ment” with an immediate right of reentry and all notices

required by law waived, if the tenant misrepresents a ma

terial fact in his application or if “the tenant fails to

comply with any of the provisions of this lease” (R. 16).

Dwelling Lease will be cancelled effective August 31, 1965, at which

time you will be required to vacate the premises you now occupy

(R. 18).

6

Among the enumerated provisions of the lease which a

tenant must comply with, and which might support termi

nation of the lease in the event of non-compliance, are

agreements by the tenant, inter alia, to pay rent when due;

to pay for damages to the premises; to pay a penalty for

excess consumption of electricity, gas or water; not to

assign the lease or sublet or accommodate boarders or

lodgers or use the premises other than as a dwelling for

the tenant and his family; to keep the premises in “a clean

and sanitary condition” ; to “maintain the yard in a neat

and orderly manner” ; to “assist in the maintenance of the

project” ; “not to use the premises for any illegal or im

moral purposes” ; not to keep dogs or pets; not to make

repairs or alterations without consent; “to follow all rules

or regulations prescribed by the Management concerning

the use and care of the premises” ; to permit management

to enter for repairs, etc.; to submit an annual income state

ment to Management; and to notify Management “ of any

increase or decrease in family income or of any change

in family composition or assets” (R. 13-14). Another sec

tion of the lease allows the Management to terminate on

30 days notice at the end of any calendar month if the

tenant’s income “exceeds the limits established for eligible

occupancy” (R. 15). Still another section provides that the

tenant will “promptly” vacate the premises if he falsely

warrants that neither he nor any person who is to occupy

the premises is a member of an organization listed as

subversive by the Attorney General of the United States,

or if he becomes a member of such an organization.

Despite the notice of cancellation of her lease, when she

was given no reason and no hearing petitioner refused

to vacate the premises. On September 17, the Housing

Authority instituted a summary ejectment action against

petitioner in the Justice of the Peace Court in Durham.

See Gen. Stats, of N.C. §42-26 et seq., infra, pp. 23a-27a.

7

On September 20, the Justice of the Peace ordered that

petitioner be removed from the premises (E. 4-5). Peti

tioner appealed to the Superior Court of Durham County

(R. 4), where evidence was submitted in the form of a

stipulation and petitioner’s affidavit.

In the Superior Court petitioner filed a motion to quash

the eviction proceedings and alleged therein that she had

a right to her apartment and that a deprivation of that

right without a hearing violated due process of law. Fur

ther, it was alleged that the defendant’s eviction resulted

primarily from her activities as a organizer of tenants

(R. 10-11). These allegations were supported by peti

tioner’s affidavit (R. 7-10). In the stipulation entered into

between petitioner and the Housing Authority (R. 7-10), it

was stipulated, inter alia, that the Housing Authority did

not give petitioner a reason for its termination of the lease

nor did it give her a hearing despite her request for one;

that on August 10, 1965, defendant was elected president

of the Parents Club and that the eviction notice was sent

out on August 11, and that the executive director of the

Housing Authority would testify, as he had testified before

the justice of the peace, that

. . . whatever reason there may have been, if any, for

giving notice to Joyce C. Thorpe of the termination

of her lease, it was not for the reason that she was

elected president of any group organized in McDougald

Terrace . . . and not for any of the other reasons set

forth in the affidavit . . . (R. 7).

Finally, it was stipulated and agreed that the judge could

determine the case by finding facts based on the stipula

tion and affidavits, Ibid.

On the basis of the stipulation, the Superior Court made

the finding:

8

That the plaintiff Housing Authority of the City of

Durham . . . gave notice to the defendant to vacate

said premises not because she had engaged in efforts

to organize the tenants of McDougald Terrace, nor

because she was elected president of a group organ

ized in McDougald Terrace on August 19, 1965; that

these were not the reasons said notice was given and

eviction undertaken (R. 21).

The Court went on to find that the Housing Authority gave

no reason to petitioner for terminating the lease and did

not conduct any hearing at which the defendant was

present or invited to be present to inquire into the reasons

for terminating the lease and, further, that although the

defendant requested a hearing, she had no hearing other

than that “before the Justice of the Peace in this eviction

action and in this Court” (R. 22). The Court then con

cluded as a matter of law that the Housing Authority of

the City of Durham had no duty to hold a hearing on the

subject of petitioner’s eviction or to communicate or give

to the defendant any reason for the termination. Thus,

the Court affirmed the judgment of the eviction (R. 23).

Subsequently, petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court

of North Carolina, raising as error the above findings of

fact and conclusions of law (R. 25). On May 25, 1966, in

a per curiam decision, the Supreme Court affirmed the

order to evict. It held, in effect, that the Authority was

under no obligation to conduct a hearing or advise the

tenant of its reasons for terminating the lease, apparently

since its obligations to its tenants were the same as the

obligations of a private landlord. Thus, the Court said:

It is immaterial what may have been the reasons for

the lessor’s unwillingness to continue the relationship

9

of landlord and tenant after the expiration of the term

as provided in the lease (R. 26-28).

The petitioner and her children have remained in posses

sion of their apartment under a stay granted by the Su

preme Court of North Carolina, pending decision in this

Court.

Summary of Argument

Petitioner was denied due process by the cancellation of

her low-income public housing benefit without notice of the

reason for eviction or any administrative hearing to contest

the cancellation. Her claim arose on an assertion that her

First Amendment rights were violated by the Housing Au

thority of the City of Durham, an agency of the state and

federal governments subject to constitutional restraints.

( The courts below upheld the claim of the Authority that

it could act arbitrarily, without a reason, relying on prin

ciples applicable to private landlords.

I.

Governmental agencies acting as landlords are neverthe

less subject to Due Process restraints against arbitrary

action. Nothing in either the federal or state statutes under

which the Durham Authority was established confers an

arbitrary power to evict. Indeed, arbitrary evictions sub

vert the purposes of the federal-state program to protect

low income citizens from the effects of inadequate slum

housing.

* * * < * ■ +

Overriding constitutional concerns defeat any claim of

arbitrary power to evict public housing tenants. The gov

ernmental agencies plainly cannot evict for a variety of

reasons under the Constitution, including racial or religions

discrimination, suppression of free speech, or (as petitioner

1 0

charged) interference with the right of free association.

Government may not condition the availability of public

benefits so as to restrict First Amendment rights. Sherbert

v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513.

The general principle against arbitrary action by govern

ment officials applies with equal force to government hous

ing project managers who claim broad authority over the

lives of those living in the projects. Tucker v. Texas, 326

Petitioner was entitled, at the bare minimum, to notice

of the reason for the cancellation of her governmental

benefit of low income housing. Notice of the ground for

governmental action is basic to the concept of Due Process.

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1; Willner v. Committee

on Character & Fitness, 373 U.S. 96. The authority has no

substantial interest in secrecy. Disclosure would promote

responsible action by the agency and insure that there is

a reason for its action. Secrecy merely shields arbitrari

ness. The petitioner’s interest in low-income housing is

precious. When denied decent housing she is remitted to

the misery of the slums, a penalty which may be “an almost

insufferable burden,” Berman v. Parker, 348 U.S. 26, 32.

The housing agency may not make surrender of the right

to notice a condition of tenancy because of the doctrine

forbidding imposition of unconstitutional conditions as the

price of governmental benefits. Sherbert v. Verner, 374

U.S. 398; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513; cf. Frost Truck

ing Co. v. Railroad Commission, 271 U.S. 583. In any event,

the lease was not a clear and explicit waiver of the right

to notice of a reason for cancellation. Indeed, the lease

should be construed to require the housing management to

give a reason for eviction. The lease may be construed by

1 1

tiiis Court under federal principles of law. Clearfield Trust

Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363.

III.

Petitioner was entitled to an administrative hearing. An

opportunity to offer proof when factual issues determine

vital interests is basic to due process in administrative

proceedings. The rule that a hearing is a fundamental re

quirement to preserve Due Process—freedom from arbi

trary, capricious or discriminatory official action—has been

developed in a variety of contexts. Japanese Immigrant

Case (Yamataya v. Fisher), 189 U.S. 86; Londoner v. Den

ver, 210 U.S. 373; Southern R. Co. v. Virginia, 290 U.S.

190; l.G.C. v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 227 U.S. 88; Morgan

v. United States, 304 U.S. 1; Slochower v. Board of Higher

Education, 350 U.S. 551; Dixon v. Alabama State Board

of Education, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961); WiUner v. Com

mittee on Character & Fitness, 373 U.S. 96.

By each of the tests stated by Mr. Justice Frankfurter

in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U.S.

123, 163 (concurring opinion), petitioner is entitled to a

hearing. Her injury is potentially grave; she has been

treated arbitrarily. The Durham Housing Authority has

statutory powers to conduct a hearing, including issuing

subpoenas, administering oaths, and other incidents of fair

procedure. Petitioner’s First Amendment claim should be

decided only after rigorous procedural safeguards. Such

safeguards are needed to insure against arbitrariness.

Rejection of the right to a hearing on the basis of the

lease provision was improper. The lease contained no ex

press waiver of a hearing. For the government agency to

require waiver of a hearing to obtain low-income housing

is to impose an unconstitutional condition. Sherbert v.

Verner, 374 U.S. 398; Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513.

1 2

ARGUMENT

Petitioner Was Denied Dee Process of Law by Her

Eviction From a State and Federally Supported Low-

Income Housing Project in the Absence of Any Pro

cedures to Give Her Any Notice of the Reason for the

Eviction or Any Hearing to Contest the Basis for the

Governmental Action.

In trod u ction

This case involves whether a municipal housing author

ity, acting as the agent of both the state and federal gov

ernments, violates the due process clauses of the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments,2 when it terminates housing

benefits it is charged by law to furnish to a citizen, with

out affording the citizen either a statement of the reason

for cancellation, or a hearing to contest its action. The

case arises in the context of an assertion that petitioner

was evicted to punish her exercise of First Amendment

rights to freedom of association.

Although it is incontestable that the Housing Authority

of the City of Durham is a governmental agency subject

to the restraints of the Constitution, the Supreme Court of

North Carolina decided that no procedural protection

was required. Without mentioning the governmental char-

2 The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to the

Housing Authority of the City of Durham, because it is a state agency,

established and operated in accordance with state law (R. 5; Gen. Stats,

o f N.C. §157-9). The Due Process Clause o f the Fifth Amendment is

also applicable because the Authority acts as an “agent for the federal

government” (Gen. Stats, of N.C. § 157-9) in the operation and man

agement of the housing project pursuant to a contract with the Federal

Government (R. 5). By law the Authority is a “ public body and a body

corporate and politic, exercising public powers” (Gen. Stats, o f N.C.

§157-9) {infra, Appendix, p. 14a).

13

acter of the agency, the Court applied to it the same legal

principles that it would apply to a private non-govern

mental landlord. The State Court thus sanctioned and

enforced the Authority’s action cancelling petitioner’s bene

fits under the public housing laws at its mere will or whim.

It reasoned that petitioner had no rights to the housing

except those conferred by her lease; that under the lease

the Housing Authority had the right to terminate; and

that it “is immaterial what may have been the reason for

the lessor’s unwillingness to continue the relationship of

landlord and tenant after the expiration of the term as

provided in the lease” (R. 28).

On this record it cannot be assumed that the Authority

acted on any reasonable ground. Rather, it was testing

its right to be arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable, and

the Court thus sanctioned wholly arbitrary governmental

action. This, we submit, is the net effect of the proceed

ings below, which included: (1) petitioner’s affidavit that

she was evicted the day after she was elected President

of a tenant organization and that she believed the reason

was an official’s opposition to her effort to organize tenants

(R. 8); (2) the official’s stipulated testimony that his rea

son “if any” was not the reason alleged by plaintiff (R. 7);

(3) the trial court’s decision that the authority had no

“duty to communicate or give . . . any reason” (R. 23) ; (4)

confirmed by the appellate decision that the reason “is

immaterial” (R. 28). Plainly, the case was viewed by the

parties and the courts below as a test of the right of the

Authority to evict arbitrarily and without any reason, any

statement of a reason, or any hearing on the reason or

lack of a reason.

Petitioner urges in detail below that the result reached

in the state courts is inconsistent with the requirements of

Due Process. We urge, first, that the Constitution pre-

14

eludes arbitrary, discriminatory or capricious action to

withhold from an individual the benefits of the state-federal

public housing program for the poor. Second, we submit

that a minimum necessary protection against arbitrary

action is that the Housing Authority be required to re

veal the reason for its action. Third, we assert that due

process requires that tenants in low-income governmentally

operated projects be given some opportunity to be heard

in order to offer such proof as may be appropriate to con

test the asserted factual basis for the government’s evic

tion orders.

I.

Public Housing Agencies May Not Evict Tenants

Arbitrarily.

We urge that the Court reject the Durham Housing

Authority’s claim of an absolute and arbitrary power to

deny the benefits of its program for low-income families

at its mere will or whim. Such a claim comes late, far too

late, in our constitutional history.3 As a unanimous Court

said in 1886: “When we consider the nature and the theory

of our institutions of government, the principles upon which

they are supposed to rest, and view the history of their

development, we are constrained to conclude they do not

mean to leave room for the play and action of purely

personal and arbitrary power.” Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356, 369. The essence of Due Process is “the protec

tion of the individual against arbitrary action.” Ohio Bell

Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Com., 301 U.S. 292, 302

(Mr. Justice Cardozo); Slochower v. Board of Higher Edu

cation, 350 U.S. 551, 559. This was stated with clarity in

its application to a government housing authority in Rud-

Cf. Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 404-405, and cases cited.

15

der v. United States, 226 F.2d 51, 53 (D.C. Cir. 1955), where

Judge Edgerton wrote:

The government as landlord is still the government.

It must not act arbitrarily, for, unlike private land

lords, it is subject to the requirements of due process

of law. Arbitrary action is not due process.

Similar reasoning has been followed—and we think rightly

so—by state courts in New Jersey, California, Wisconsin

and Illinois, holding that public housing authorities are

subject to the Due Process Clause. Kutcher v. Housing

Authority of Newark, 20 N.J. 181, 119 A.2d 1 (1955);

Housing Authority of Los Angeles v. Cordova, 130 Cal.

App.2d 883, 279 P.2d 215 (App. Dept. Super. Ct. 1955);

Lawson v. Housing Authority of City of Milwaukee, 270

Wise. 269, 70 N.W. 2d 605 (1955), cert, denied, 350 U.S. 882

(1955); Chicago Housing Authority v. Blackman, 4 111. 2d

319, 122 N.E. 2d 522 (1954). Cf. Williams v. City of Ypsi-

lanti, Civil Action No. 28936, D.Mich., 1966 (Temporary

injunction barring eviction of woman who had an illegiti

mate child); Holt v. Richmond Redevelopment and Hous

ing Authority, Civil Action No. 4746, E.D. Va,, Sept. 7,

1966. The Housing Authority’s claim to arbitrary power

must be found wanting for a host of reasons.

There is nothing in either the federal4 or state acts6

creating the publicly supported low-income housing pro

gram administered by the Durham Authority which ex

pressly confers an arbitrary power to evict, or otherwise

withhold the benefits of the program. Neither of the two

provisions of the federal law which authorize the local

4 The United States Housing Act of 1937, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1401

et seq., p. la , Appendix, infra.

6 The North Carolina "Housing Authorities Law,” Gen. Stats, o f North

Carolina, § 157-1 et seq., p. 10a, Appendix, infra.

1 6

agencies to require tenants to move from low-income

projects (42 U.S.C. §1410(g)(3) and 42 U.S.C. §1404a)

grants arbitrary power; both provisions are related to a

policy of limiting occupancy to low-income families. The

only provision of the state “Housing Authorities Law”

about tenant selection also refers only to the income lim

itation (Gen. Stats. NIC. §157-29). The text of 42 U.S.C.

§1410 (g) (3) (Appendix, infra, p. 7a), makes plain that it

relates only to enforcement of maximum income limitations

in low-income projects.6 The other provision, 42 U.S.C.

§1404a, serves this same purpose, although the purpose

becomes completely apparent only from review of the

legislative history. Section 1404a, provides, inter alia:

Notwithstanding any other provisions of law except

provisions of law enacted after August 10, 1948 ex

pressly in limitation hereof, the Public Housing Ad

ministration, or any State or local public agency

administering a low-rent housing project assisted pur

suant to this chapter or sections 1501-1505 of this title,

shall continue to have the right to maintain an action

or proceeding to recover possession of any housing

accommodations operated by it where such action is

authorised by the statute or regulations under which

such housing accommodations are administered, and,

in determining net income for the purposes of tenant

eligibility with respect to low-rent housing projects

assisted pursuant to this chapter and sections 1501-

1505 of this title, the Public Housing Administration

is authorized, where it finds such action equitable and

in the public interest, to exclude amounts or portions

6 The provision, added in 1961, 75 Stat. 164 (Act of June 30, 1961,

Section 205) states that federal contribution contracts must provide that

local agencies make periodic reexaminations of tenant’s incomes and re

quire tenants above the maximum income limits to move from the project,

except in special circumstances.

17

thereof paid by the United States Government for dis

ability or death occurring in connection with military

service. (Emphasis supplied.)

The history of the provision, and its statutory predecessor

amply demonstrates that §1404a was enacted to allow

eviction of tenants above the income limits for low-income

projects; nothing in the legislative history supports a

claimed power to evict without cause.7 There is no in-

7 The quoted provisions of section 1404a were enacted in the Housing

Act of 1948, Title Y, §502 (b), 62 Stat. 1284. This was a reenactment,

with slight changes of wording, of a provision adopted a year earlier in

the Housing and Rent Act of 1947, Title II, §209 (b), 61 Stat. 201.

Senator Ellender, who introduced the Section as an amendment made

clear that the purpose was to permit evictions to enforce the income limi

tations :

“ Mr. B uck . A s I understand the amendment, it would permit the

Housing Authority to remove from public housing units tenants who

are now earning an income greater than that which would enable

them to qualify for occupancy o f low-cost public housing units V’

“ Mr . E llender. That is correct. . . . There are many tenants in some

of the public housing projects at the moment who can pay an eco

nomical rent. . . . [T]he purpose of the amendment is to make it

possible for the authorities in charge of public housing to be able

to evict those who are not entitled to be there.” 93 Cong. Bee. 6044

(1947).

One month after the 1947 version was enacted, Congress passed a law

allowing local ag’encies to postpone the commencement of eviction pro

ceedings until March 1, 1948, if undue hardship would result for the

occupants. Aet of July 31, 1947, C.418, §2, 61 Stat. 705, (formerly 42

U.S.C. §1413a).

As indicated the 1948 version was basically a reenactment o f the pro

vision inserted in 1947. The 1948 version was proposed by a Senate sub

committee; tbe chairman made clear that it was a “ provision for the

eviction of over-income tenants.” 94 Cong. Rec. 9867 (1948) (remarks

of Senator McCarthy) :

. . . [W ]e also have a provision for the eviction of over-income

tenants in the present 190,000 public housing units. We do not

provide that they must be evicted instanter. We provide that the

F.P.H.A., the local housing agency, shall evict them in an orderly

manner, and I understand they have a program of evicting 5 per

cent each month on 6 month’s notice.

18

dication that Congress made a judgment to grant arbitrary

power.

Furthermore, the claim of arbitrary power is inconsis

tent with the expressed purposes of the state-federal

low-income housing program. The policy of the United

States is :

. . . to promote the general welfare of the Nation

by employing its fund and credit, . . . to assist the

several States and their political subdivisions to al

leviate present and recurring unemployment and to

remedy the unsafe and insanitary housing conditions

and the acute shortage of decent, safe, and sanitary

dwellings for families of low income, in urban and

rural nonfarm areas, that are injurious to the health,

safety, and morals of the citizens of the Nation. 42

U.S.C. §1401.

The North Carolina enactment contained an even more

detailed declaration of the necessity of the program for

low-income housing to correct conditions which it found

“cannot be remedied by the ordinary operation of private

enterprise.” Gen. Stats. N.C. § 157-2 (reprinted Appendix,

infra, p. 10a).8 * Indeed, there must be specific findings as to

the need for low income housing in order for a municipality

to establish a housing authority under the North Carolina

law (Gen. Stats, of N.C. § 157-4), or for such an authority

to obtain federal funds (42 U.S.C. §1415(7)). The state

and federal statutory schemes make it plain that the

public housing agencies are not acting as private land

lords, furnishing housing as business proprietors. The

program is rather an exercise of the general governmental

power to protect the health, safety, and welfare of an

8 See also the similar declarations in Gen. Stats, o f N.C. §§157-40,

157-48.

19

economically disadvantaged segment of the citizenry.9 The

initiation of the program rested on explicit recognition

of the fact that without public housing large number of

persons would be condemned to live in urban and rural

slums, suffering all the injuries stemming from unsafe and

unsanitary dwellings.10

A power to evict tenants of public housing capriciously

or without a reason is not merely inconsistent with the

purposes of the program; it actually undermines and sub

verts them. Such arbitrary power necessarily places pub

lic housing tenants in “a state of insecurity,” as the com

mentators have observed.11 ’Thus, the intended benefits—

family stability and security in a decent and safe environ

ment—are negated. This naturally reduces the attractive

ness of public housing for slum residents, even though

housing is their primary problem.12 More directly, of

9 As stated in Powell v. Eastern Carolina Regional Housing Auth., 251

N.C. 812, 112 S.E.2d 386, 387, “ The Legislature authorized the creation

of housing authorities as a means of protecting low-income citizens from

unsafe or unsanitary conditions in urban or rural areas, G.S. § 157-2.”

10 Gen. Stats, o f N.C. § 157-2, found, inter alia, “ the existence o f hous

ing conditions which endanger life or property by fire and other causes” ,

and that “ these conditions cause an increase in and spread of disease and

crime and constitute a menace to the health, safety, morals and welfare

of the citizens. . . . ”

11 Reich, Individual Rights and Social W elfare: The Emerging Legal

Issues, 74 Y ale L. J. 1245, 1250. As observed by Alvin Schorr of the

U. S. Dept, o f Health, Education, and Welfare, some tenants find housing

regulations and penalties “ to be precisely a confirmation of their greatest

anxiety, that they were being offered decent housing in exchange for their

independence.” Schorr, Slums and Social I nsecurity (Dept, of H.E.W.

Research Report No. 1), p. 112 (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington,

D. C. 1963).

12 Studies indicate the distaste of slum residents for the rules, regula

tions and control over their lives which accompany public housing, and

the marked lack of desire o f many eligible slum residents to move to

public housing. Sternlieb, T he T enement L andlord, Rutgers LTniv. Press

(1965), pp. 14-15; Millspaugh, Problems and Opportunities of Reloca

tion, 26 Law & Contemp. P rob. 6, 11-12 (1961).

20

course, every actual exercise of an arbitrary power to

evict a public bousing tenant, remits the tenant and his

family to the slums, subjecting them to all the injuries

stemming from residence in unsafe and unsanitary dwel

lings, which the program is supposed to prevent.

Of course, putting aside the provisions and purposes of

the housing acts, there are overriding constitutional con

cerns which make it plain that the claimed right to act

for any reason, or for no reason, must fail. There plainly

are some reasons which could not constitutionally support

housing authority action. For example, it has been widely

held that a public housing authority violates the Four

teenth Amendment by a policy of refusing to lease units

to qualified Negroes because of their race. Detroit Hous

ing Commission v. Lewis, 226 F.2d 180 (6th Cir. 1955).13

Race, or a desire to enforce racial segregation, must

equally be a forbidden ground for eviction from a govern

ment project, lest the power to discriminate be absolute.

It should be equally be made clear that a public housing

authority may not bar citizens on the basis of their reli

gion, or their ideas on public issues in violation of First

Amendment guarantees. Petitioner’s case arises not from

a racial discrimination claim, but, rather, in the context

of her assertion that she is being punished for exercising

First Amendment rights of free association in a tenant’s

13 Other such cases are Jones v. City of Hamtramck, 121 F. Supp. 123,

(E.D. Mich. 1954) ; Vann v. Toledo Metropolitan Housing Authority, 113

F. Supp. 210 (N.D. Ohio 1953); Banks v. Housing Authority of City

and County of San Francisco, 120 Cal. App.2d 1, 260 P.2d 668 (1953),

cert, denied, 347 U.S. 974 (1954); Taylor v. Leonard, 30 N.J. Super.

116, 103 A.2d 632 (1954). See Executive Order No. 11063, 27 Fed. Reg.

11527 (1962), prohibiting racial discrimination in federally assisted hous

ing. And see Title V I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 252, 42

U.S.C. § 2000d, and the implementing regulations (24 C.F.R., Subtitle A,

Part 1) prohibiting discrimination in federally assisted programs, includ

ing low-rent housing projects.

21

organization. This Court’s decisions expressing concern

for the procedures by which First Amendment claims

are determined (ef. Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513),

leave no room for an absolute power to conceal violations

of the Amendment. This Court has condemned rules which

condition the availability of public benefits so as to re

strict First Amendment rights. In Sherbert v. Verner,

374 U.S. 398, 404, the Court said:

It is too late in the day to doubt that the liberties

of religion and expression may be infringed by the

denial of or placing of conditions upon a benefit or

privilege. American Communications Asso. v. Douds,

339 U.S. 382, 390; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S.

183, 191, 192; Hannegan v. Esquire, Inc., 327 U.S. 146,

155, 156. . . . In Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, we

emphasized that conditions upon public benefits cannot

be sustained if they so operate, whatever their purpose,

as to inhibit or deter the exercise of' First Amendment

freedoms.

The principle was applied in Speiser v. Randall, 357

U.S. 513, to invalidate state action limiting the availability

of a tax exemption in a manner which inhibited free

speech. The rule is necessary lest the State “produce a

result which . . . [it] could not command directly” 357

U.S. at 526. Applying these principles, we submit that

it could not be gainsaid that a public housing authority

could not bar a citizen from occupancy in a project for

failure to make a religious oath (ef. Torcaso v. Watkins,

367 U.S. 488), or for refusal to make an unconstitutionally

vague oath (cf. Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368

U.S. 278, 288), or to punish innocent membership in a

proscribed organization (cf. Wieman v. Updegraff, 344

2 2

XJ.S. 183, 192),14 or to suppress freedom of association

to advance political views (cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371

XJ.S. 415). There is no reason whatever to suppose that

the restraints of the Constitution do not apply with equal

force to the manager of a federally operated or supported

housing project. T-ucher v. Texas, 326 U.S. 517.

Tucker v. Texas, supra, held that the manager of a fed

eral housing development for defense workers unconstitu

tionally suppressed the distribution of religious literature

by seeking to exercise a licensing power. This manager

had claimed “full authority to regulate the conduct of

those living in the village” (326 XJ.S. at 519), in support

of his order that a Jehovah’s Witness discontinue all re

ligious activity in the village (id.). The Court rejected the

claim of arbitrary power over freedom of the press and

religion and reversed state criminal convictions which en

forced the manager’s invalid assertion of authority over

the tenants’ lives.

We submit that reason and authority reject the Durham

Authority’s claimed right to act unreasonably in termi

nating the benefits of the program it administers. Of

course, the Authority, like other governmental agencies,

may constitutionally be given a substantial degree of con

trol over the use and occupancy of its projects, to effi

ciently manage and fulfill the purposes of its program.

We do not stop to fully explore the detailed scope of the

Authority’s power to make, and to enforce by evictions,

rules for the conduct of tenants needed to protect its prop

erty and other tenants, because no one would deny that

14 The Court said in Wieman {supra, 344 U.S. at 192) :

We need not pause to consider whether an abstract right to public

employment exists. It is sufficient to say that constitutional protec

tion does extend to the public servant whose exclusion pursuant to a

statute is patently arbitrary or discriminatory.

23

the Authority must have powers to accomplish these ends.

The issue herefis not whether a public housing agency may

evict on a reasonable ground, or whether or not a particu

lar ground is reasonable. The issue is whether a govern

ment agency may evict for

ft® aa^eiews reason, recognizing that the power to be ca

pricious includes a practical power to act for reasons

specifically forbidden by the Constitution. The answer to

that question must be negative if there is to be any pro

tection at all for the civil rights and civil liberties of pub

lic housing tenants. Rudder v. United States, 226 F.2d 51

(D.C. Cir. 1955). Otherwise, minor bureaucrats—housing

project managers—are granted “full authority to regulate

the conduct of those living in the [project].” Tucker v.

Texas, 326 U.S. 517, 519.

So we now turn to another vital question. What does

procedural due process require to give protection against

discriminatory, arbitrary, capricious and unconstitutional

action terminating public housing benefits?

II.

Petitioner Was Entitled to Notice o f the Reason Her

Low-Income Housing Benefits Were Cancelled.

Whatever may be decided with respect to petitioner’s

claim (discussed in Part III below) that she had a right

to a hearing before eviction, petitioner was at the very

least entitled to notice of the reason, if any, for the Hous

ing Authority’s action requiring her to move from the

project. Notice of the reasons for proposed governmental

action adversely affecting a citizen’s interests has been

regarded as an essential element of due process in a

variety of contexts. Willner v. Committee on Character &

24

Fitness, 373 U.S. 96, 105-106; Morgan v. United States, 304

U.S. 1, 18, 19; cf. Gonzales v. United States, 348 U.S. 407.

If there is even to be any potential protection against

arbitrary action by public housing officials, the officials

must at the very least be required to formulate and articu

late a reason for an eviction, and notify the tenant of that

reason in writing. Notice of reasons would at least offer

a possibility of relief if an official is mistaken about the

facts and he or some reviewing authority can be persuaded

that he is mistaken, or if the official is mistaken about the

law and it can be shown that the proposed action violates

the law, or if the official acts contrary to policy estab

lished by superior administrative officials. A requirement

that the housing agency state its reason for terminating-

low income benefits serves the salutary function of re

quiring that the agency act responsibly and actually have

a reason. It is a protection against capricious action.

The Authority has no substantial interested to be served

by keeping its reason secret. Such secrecy does nothing to

further the purposes of the state-federal program to pro

vide housing assistance to the poor. We have seen no

proffered justification for a policy of secrecy. If the Hous

ing Authority has a good reason for evicting a tenant,

there is no impediment to its stating that reason and rely

ing on it as the basis for eviction. There are no consider

ations of immediate danger to the public or of peril to the

National Security or other similar factors which might

justify the Authority’s reluctance to give tenants notice

of the reasons for eviction. The Authority’s refusal to

accord its tenants reasonable protection can only help to

break the spirits of the evicted tenants, and of other mem

bers of the community familiar with the injustice, and

increase the apathy and despair of the impoverished. The

policy of secrecy serves only as a shield for arbitrariness.

25

It is, of course, more convenient for a bureaucrat to have

arbitrary power and to be unaccountable for his acts. But

as Mr. Justice Frankfurter put it: “ Secrecy is not con

genial to truth-seeking and self-righteousness gives too

slender an assurance of rightness.” Joint Anti-Fascist

Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 171 (con

curring opinion). Indeed, it is in the “manifest interest”

of government agencies to be fair, and to appear to be

fair, in their dealings with citizens they are charged with

assisting. Cf. Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1, 22. A

policy of secrecy in evictions sacrifices the deterrent value

which might be gained from announced enforcement of

reasonable rules and regulations, and merely promotes

generalized fear and insecurity on the part of tenants.

The tenant of public low income housing has a strong

interest in continued eligibility for public housing benefits

and in being informed of the reason the authorities may

have for cancelling such benefits. The value of the tenant’s

interest in public housing may be measured by the govern

mental findings which justify providing the benefits (42

U.S.C. §1401; Gen. Stats, of N.C. §157-2). The essence of

the matter is that the tenant is provided public housing

only because he would be otherwise unable to obtain decent

and sanitary housing, and when the tenant is denied

decent housing he is remitted to slums, including:

. . . such unsafe or unsanitary conditions [that] arise

from overcrowding and concentration of population,

the obsolete and poor condition of the buildings, im

proper planning, excessive land coverage, lack of

proper light, air and space, unsanitary design and

arrangement, lack of proper sanitary facilities, and

the existence of conditions which endanger life or

property by fire and other causes; * * * [which] con

ditions cause an increase in and spread of disease and

26

crime and constitute a menace to the health, safety,

morals and welfare of the citizens of the State and

impair economic values . . . ” (Gen. Stats, of N.C.

§157-2).

The federal and state governments have found that un

less they provide Mrs. Thorpe and others in her economic

position decent and sanitary housing, they will be con

demned to live in slum conditions which pose a constant

threat to their health, safety and morals. Thus, the inter

est of petitioner is no less than the interest in being able

to live at a minimum level of decency and comfort. And,

of course, petitioner, and society in general have an inter

est in her freedom to exercise her rights of free speech

and free association without fear of a crushing reprisal.

The effect of being remitted to live in slum conditions

can be incalculable. It is punishment in a real sense. The

impact of such decisions on the children of the poor may

influence the entire course of their lives. And where a

Negro family is involved, as in petitioner’s case, a return

to the slums may quite likely mean a return to a racial

ghetto. This Court described the problem in Berman v.

Parker, 348 U.S. 26, 32, where Mr. Justice Douglas wrote:

Miserable and disreputable housing conditions may do

more than spread disease and crime and immorality.

They may also suffocate the spirit by reducing the

people who live there to the status of cattle. They

may indeed make living an almost insufferable burden.

The tenant’s interest in knowing the grounds for eviction

is compelling. This minimal protection against arbitrari

ness may at least afford a channel for relief in some cases

of injustice. Knowing the ground for the official action

may afford a basis for informal complaint or request for

27

reconsideration, for an appeal to higher executive author

ity, for an appeal for legislative reform or relief, or for

an appeal to the courts. Minimal fairness requires that

petitioner be apprised of the reason for a curtailment of

benefits she is entitled to receive under a program of bene

fits for poor persons. Petitioner is entitled to know the

claims of those who would deprive her of governmental

benefits. Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1. The right

to know a reason for official action is vital so long as

there remains any conceivable method, however informal,

of influencing that action. Gonzales v. United States, 348

U.S. 407, illustrates the point. In Gonzales, supra, a draft

registrant was held entitled to have a copy of an “advisory

recommendation” made by the Department of Justice to

his Selective Service Appeal Board, and to an opportunity

to file a reply. Though there was no hearing before the

appeal board and the statute involved was silent on the

right to know the recommendations, the Court found that

this right was implicit in the Act “viewed against our

underlying concepts of procedural regularity and basic

fair play” (348 U.S. at 412).15

The great value to a tenant of a rule requiring that the

Housing Authority disclose its asserted justification for

eviction is demonstrated by a recent case involving claims

similar to petitioner’s. In Holt v. Richmond Redevelop

ment and Housing Authority, Civil Action No. 4746, E.D.

Va., September 7, 1966, a tenant sued under 42 U.S.C. §1983

to restrain his eviction from a public housing project on

the ground that the authority’s purpose was to punish

him for his tenant-organizing activities. The housing au

thority answered by asserting that the reason for eviction

16 Cf. Simmons V. United States, 348 U.S. 397, finding a deprivation

of the fair hearing required by the selective service law in the failure

to furnish a fair resume of an adverse FBI report considered by the

hearing officer.

was the plaintiff’s failure to report all of his income in

violation of a lease provision, and not his organizing ac

tivities. The plaintiff then proved the circumstances con

cerning his income and his organization’s disputes with

the authority. The Federal District Court (Butzner, J.)

found the authority’s asserted reason for eviction un

founded, and that the actual reason was plaintiff’s con

stitutionally protected activity, and restrained the evic

tion. Holt, supra, clearly shows the vice of the rule (ap

plied in this case) that the reason for eviction is “imma

terial.”

28

In the Brief in Opposition to the petition for certiorari

respondent suggests that petitioner could have learned the

“motives, if any, for the eviction,” in the course of the

summary ejectment proceedings, by cross-examination of

the housing director either during trial or by pre-trial

discovery. (Brief in Opposition, pp. 7-8). But the courts

below never rested on this ground. They took the view

that the Housing Authority had no duty to communicate

a reason (R. 23), and that the reason was “immaterial”

in a determination of the Authority’s right of possession

(R. 28). The case was tried as a test of the Authority’s

right to act without a reason, as clearly indicated by the

stipulation that the Housing Director would testify, as he

had before the Justice of the Peace that “whatever rea

son there may have been, if any, for giving notice . . . it

was not for the reason” of petitioner’s organizing activi

ties. (Emphasis supplied). There was no suggestion that

the Authority had any reason which it was prepared to

divulge and rely on. Finally, petitioner urges that dis

closure in court would not in any event cure the failure

to give a reason at the time her benefits were cancelled.

An important ground for requiring that the Authority

state a reason is to insure that the Authority will actually

29

formulate a reason and act responsibly in cutting off gov

ernmental benefits. This objective is not accomplished by

disclosure of a reason for the first time in court, when the

reason may be merely a post facto attempt to justify that

which was done for no good reason. Low-income housing

officials deal with tenants who are impoverished, and are

often ignorant of their rights. The tenants will not often

know whether to resist an order to move unless they know

the grounds of the agency’s action. They will rarely have

lawyers or the resources to go to court to find out why

they are being evicted. They should at least be told why

they are being subjected to eviction—a punishment that

is real and severe.

The courts below decided that petitioner had no right to

be informed of the grounds for eviction by relying on the

provisions of the lease. This was, in effect, a ruling that

petitioner had waived the claimed constitutional right to

notice of the reason for eviction. Conceding, arguendo, that

the lease permits eviction arbitrarily and unconstitution

ally, we urge that the government may not validly exact

such an unconstitutional condition as the price of obtain

ing low-income public housing benefits. The state-federal

agency may not exact surrender of the right to be treated

fairly and reasonably as the price of the opportunity to ob

tain decent quarters under a government program for the

poor. In Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 404, this Court

held that a state could not condition the granting of un

employment benefits on the surrender of First Amendment

rights to the free exercise of religion. The rule against un

constitutional conditions protected free speech in Speiser

v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513. The rule proscribing the imposi

tion of unconstitutional conditions has also been applied in

cases that involved: use of public highways, Frost Truck

ing Company v. Railroad Commission, 271 U.S. 583; foreign

30

corporations doing business in a state, Hanover Fire Ins.

Co. v. Harding, 272 U.S. 494; Wheeling Steel Corf. v. Glam-

der, 337 U.S. 562; and public employment, see, Torcaso v.

Watkins, 367 U.S. 488; Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479;

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 100. See

also, Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U.S. 551, 555;

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183, 191. And see, O’Neil,

Unconstitutional Conditions: Welfare Benefits with Strings

Attached, 54 Calif. L. Rev. 443 (1966).

As the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit said in Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Educa

tion, 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), upholding the right of

students to a hearing before expulsion from a public col

lege for alleged misconduct: “the right to notice and a

hearing is so fundamental to the conduct of our society

that the waiver must be clear and explicit” 294 F.2d at

157. Cf. Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458. The alleged

waiver of notice of the reasons for eviction in Mrs. Thorpe’s

lease, is by no means “clear and explicit.” There is nothing

in the lease which expressly grants the right to evict

without stating a reason. Indeed, we submit that—far from

supporting a finding of waiver—ordinary principles of

interpretation support a holding that this lease does re

quire that a ground for eviction be stated in writing. This

follows from any effort to read the variety of provisions

allowing the management to terminate so that they are

mutually consistent.

The lease states that it “ shall be automatically renewed

for successive terms of one month each” at a rental of

$29, provided, “there is no change in the income or com

position of the family of the tenant and no violation of

the terms hereof” (R. 12). The lease has four provisions

for termination by management: one allows termination

on 30 days notice; another requires only 15 days notice;

31

another provides termination “automatically at the option

of the management” without notice; and, another requires

the tenant to vacate “promptly.” 16 Unless the lease re

quires written notice of the reason for eviction, the tenant

cannot know how much notice he is entitled to receive. The

lease clearly does not contemplate, for example, that a

tenant be evicted on no notice, or on only fifteen days

notice, if the manager’s reason is that the tenant’s income

makes him ineligible. And, similarly, it does not contem

plate eviction on fifteen days notice, or at all, if the manager

believes that the tenant’s income makes him ineligible when

the actual facts are otherwise. Merely to insure that the

tenant gets what he “bargains” for (if we may use that

inapplicable word in this context), the lease may be, and

161. Management “ may terminate this lease by giving to the Tenant

notice in writing of such termination fifteen (15) days prior to the last

day of the term” (R. 12).

2. I f management determines that a tenant’s income exceeds the limits

for eligible occupancy it “may terminate at the end of any calendar month

by giving the Tenant not less than 30 days’ prior notice in writing”

(R. 15).

3. I f a tenant is a member o f an organization designated as subver

sive by the Attorney General of the United States he must vacate the

premises “ promptly” (R. 17).

4. I f a tenant makes misrepresentations in his application or if he

“ fails to comply with any of the provisions of” the lease, it is “ auto

matically terminated at the option of the management” and the tenant

“ waives all notice required by law” and management may “ immediately

re-enter said premises and dispossess the Tenant without legal notice or

the institution of any legal proceedings whatsoever” (R. 16).

The host o f provisions the tenant must comply with include, inter alia,

duties: to pay rent when due; to pay for damages and excess consump

tion of gas, water and electricity; to use the premises only for a dwell

ing; to keep the premises clean; not to keep dogs; to follow rules and

regulations; to submit an annual income statement; and to promptly

notify management of any increase or decrease in family income or any

change in family composition or assets (R. 13-14). There are numerous

other such provisions (ibid.).

32

should be, read to require that management state a reason

for a purported termination of the lease.17

In any event, the lease contains no clear waiver of the

right to notice of the reasons for eviction. It should not

lightly be presumed, from a document that is silent on the

subject, that the constitutional rights of indigent public

housing tenants have been waived. This is particularly true,

considering the fact that the leases are prepared by govern

ment agencies who stand in an infinitely superior “bargain

ing position.” Indeed, by definition, indigent public hous

ing tenants have no “bargaining position” at all. They are

offered public housing only because they have insufficient

17 This Court may independently construe the lease in accordance with

federal law. Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363; United

States v. Allegheny County, 322 U.S. 174. The lease was entered into by

the Housing Authority acting to carry out the policy o f the federal

housing law's, under a contract with the federal government and with

federal funds. The lease in question is a contract with an intended bene

ficiary of the federal program. This was not a custom-tailored lease

negotiated with specific reference to North Carolina law. Contrast: United

States v. Yazell, 382 U.S. 341; and see United States v. Helz, 314 F.2d

301 (6th Cir. 1963). Such month to month leases are commonly used by

almost every public housing agency in the country, though no federal

law requires such short terms. There is, thus, a substantial federal interest

in national uniformity in the treatment of the intended beneficiaries of

the federal program in accordance with basic standards of decency and

procedural fairness. This is not at all inconsistent with the policy of the

federal act to vest in local agencies the “maximum amount o f responsi

bility in the administration of the low-rent housing program, including

responsibility for the establishment of rents and eligibility requirements

(subject to the approval of the [Federal] Authority), with due considera

tion to accomplishing the objectives o f this chapter while effecting econo

mies” (42 U.S.C. §1401; emphasis supplied). The policy assumes a

reservoir of federal control to accomplish the objective of the Act, e.g.,

furnishing housing to the needy. Interpretation of the lease as a federal

instrument under the Clearfield Trust doctrine, would not require that fed

eral rather than state law govern contracts made by local authorities with

others. Contracts with beneficiaries of the program are plainly distinguish

able from contracts between the local agencies and builders or suppliers,

which ought to be governed by state law, consistent with the policy of

using local law as a convenient local resource to accomplish the objectives

of the program.

33

funds to obtain decent bousing' on the private market. It

blinks reality to treat low-income public housing tenants as

if they bargain with the government over the terms of

their leases.

Petitioner Was Entitled to an

ing to Contest the Cancellation of Her Low-Income

Housing Benefits.

Due process requires that petitioner be given some op

portunity to be heard to offer proof to contest the Au

thority’s action cancelling her low-income housing benefits.

The right to a hearing has long been regarded as one of

the fundamental rudiments of fair procedure necessary

where the government acts against a citizen’s vital inter

ests. Hearings are an important protection against ar

bitrariness. They are customary in our law where the deci

sion about how government will treat the citizen turns on

issues of fact. The expectable ordinary controversies that

may lead to public housing evictions need fair procedures

for fact-finding. They might involve various claims of mis

behavior by tenants affecting other tenants or the prop

erty. Tenants should have the right to have decisions

on such issues based on evidence and not on rumor or

fancy. For the indigent, eviction is a serious penalty.