Correspondence from Chambers to Wong

Correspondence

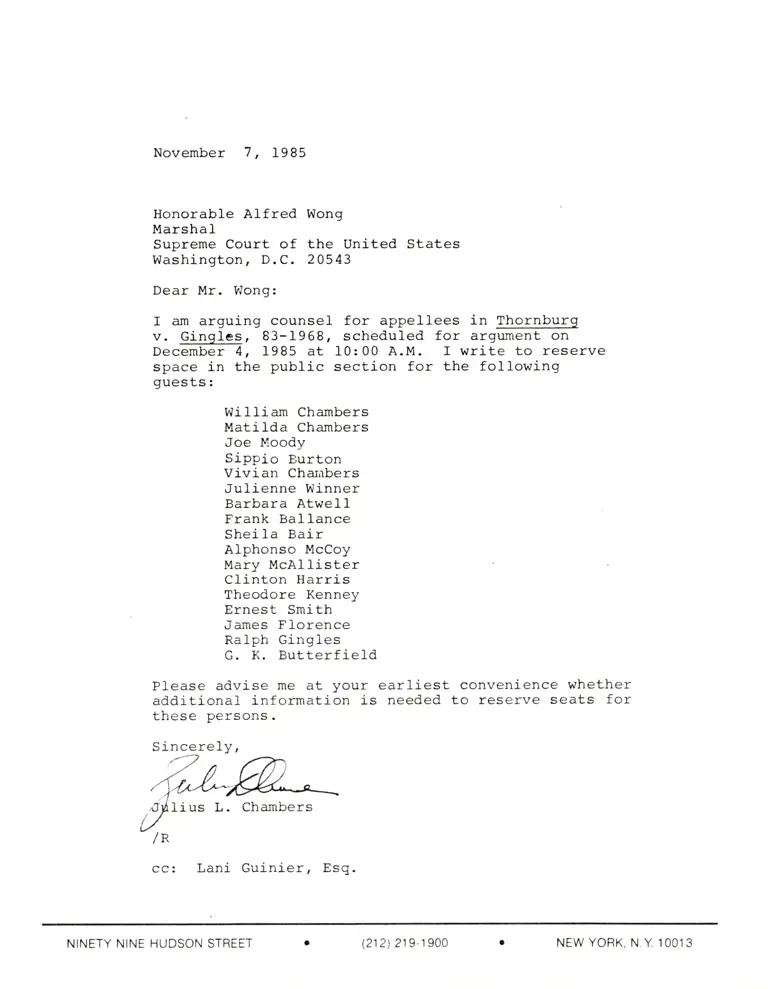

November 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Correspondence from Chambers to Wong, 1985. 316db5e7-dd92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/af1bb085-f783-4a4e-b489-153de236752d/correspondence-from-chambers-to-wong. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

November 7, 1985

Honorable Alfred Wong

I'larsha1

Supreme Court of the United States

Washington, D.C.20543

Dear 1,1r. Vlong:

I am arguing counsel for appellees in Thornburg

v. Ginqles, 83-1968, scheduled for argument on

December 4, 1985 at 10:00 A.I{. I write to reserve

space in the public section for the following

guests:

William Chambers

Matilda Chambers

Joe Irloody

Sippio Burton

Vivian Charnbers

Julienne Winner

Barbara Atwell

Frank BaIlance

Sheila Bair

Alphonso IvlcCoy

Mary McAIlj-ster

Clinton Harris

Theodore Kenney

Ernest Smith

James f'Iorence

Ralph Gingles

c. K. Butterfield

Please advise me at your earliest convenience whether

additional information is needed to reserve seats for

these persons.

Sincerely,

/R.

cc: Lani Guinier, Esq.

Chambers

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET (212) 21 9-1 900 NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013