McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

February 25, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education Brief for Appellant, 1950. 13da76c0-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/af32ab68-bb43-47c6-b5d1-2c717a107c6f/mclaurin-v-oklahoma-state-regents-for-higher-education-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

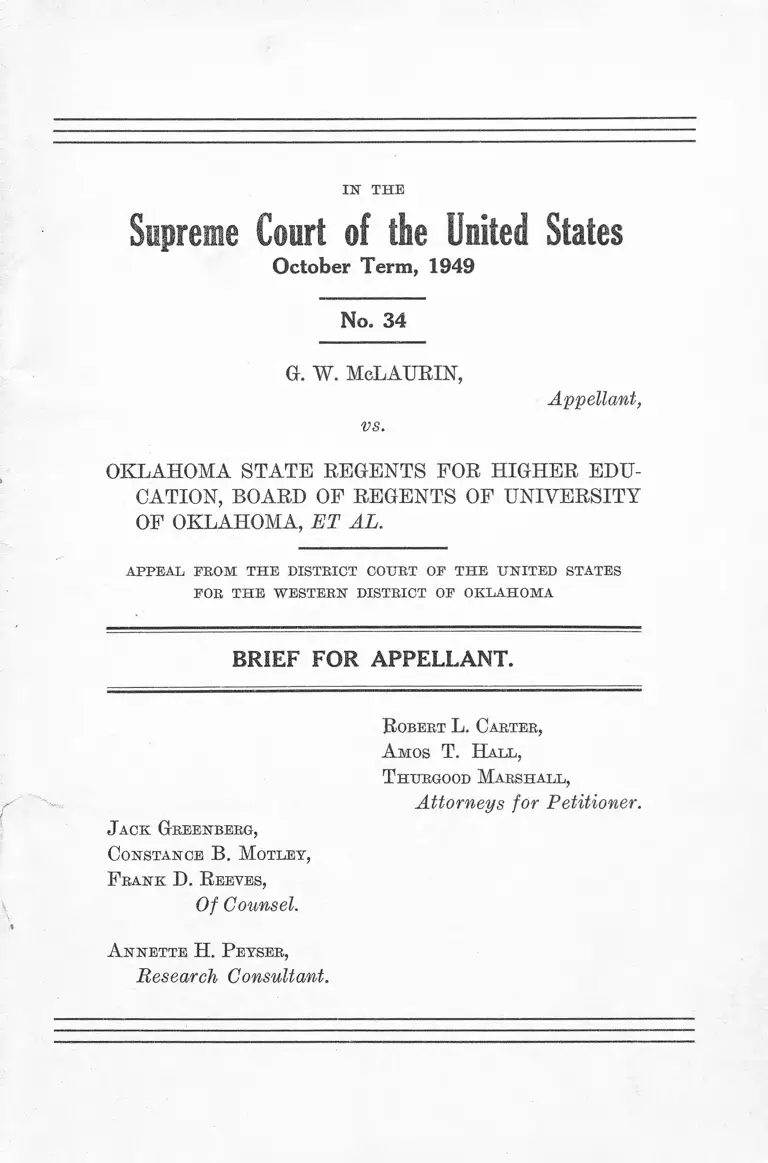

1ST THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 34

G. W. McLAURIN,

vs.

Appellant,

OKLAHOMA STATE REGENTS FOR HIGHER EDU

CATION, BOARD OF REGENTS OF UNIVERSITY

OF OKLAHOMA, ET AL.

A PPE A L FRO M T H E D ISTRICT COURT OF T H E U N IT E D STATES

FOR T H E W E STE R N D ISTRICT OF O K L A H O M A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT.

R obert L. Carter,

A mos T. H all,

T hurgood Marshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

J ack Greenberg,

Constance B. M otley,

F rank D. R eeves,

Of Counsel.

A nnette H . P eyser,

Research Consultant.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion B elow ______________________________________ 1

Statement of Jurisdiction __________________________ 2

The State Statutes and Administrative Order, the

Validity of'Which Is Involved_________________ 3

Order by Board of Regents of University of Okla

homa, a State Board, Acting Pursuant to State

Statutes, the Validity of Which Is Involved____ 5

Statement of the C ase_______________________________ 6

Question Presented__________________________________ 10

Errors Relied U p on _________________________________ 10

Summary of Argum ent______________________________ 12

Argument:

I—The exclusion of appellant from the regular class

room and the requirement of spacial segregation

solely because of race and color is in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment____________________ 15

A. The limitation on a state’s right to classify

for legislative purposes_____________________ 16

The Objectives of Public Education ________ 17

Neither Race, Ancestry Nor Skin Pigmenta

tion of Students Has Any Pertinence to the

Objectives of Public Education_____________ 22

Compulsory Racial Segregation in Public Ed

ucation Is An Arbitrary and Unlawful Clas

sification Within the General Limitations Upon

Right of States to Classify Its Citizens______ 24

B. Classifications by governmental agencies based

solely on race or ancestry are particularly

odious to our principles of equality _ 30

IX

C. The public policy of Oklahoma of requiring

racial segregation in graduate public educa

tion is in direct conflict with the federally

protected right of appellant to be free from

state imposed racial distinctions------------------- 35

II—The separate but equal doctrine should be sub

jected to critical analysis and if found to be ap

plicable to this case should be overruled------------ 36

A. The problem with which Plessy v. Ferguson

dealt is fundamentally different from the prob

lem presented here _________________________ 36

B. This is not an appropriate case for the appli

cation of the doctrine of stare decisis------------ 39

III—If this Court considers Plessy v. Ferguson ap

plicable here, that case should now be reexamined

and overruled__________________________________ 44

A. In Plessy v. Ferguson the Court did not prop

erly construe the intent of the framers of tlxe

Fourteexxth Amendment ____________________ 44

1. The Court improperly construed the Four

teenth Amendment as incorporating a doc

trine antecedent to its passage and a doc

trine which the Fourteenth Amendment had

repudiated --------------------------------------------- 44

2. The framers of the Fourteenth Amendment

and of the contemporaneous civil rights

statutes expressly rejected the constitu

tional validity of the “ sepai’ate but equal”

doctrine _________________________________ 46

Conclusion __________________________________________ 53

Appendix A ________________________________________ 55

Appendix B ---------------------- 56

PAGE

I l l

Table of Cases

Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 U. S. 499 ____________ 16

Baumgartner v. United States, 322 TJ. S. 665 __________ 18

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45_______________ 40

Board of Tax Commissioners v. Jackson, 283 U. S. 527- 16

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 2 8 ______ 37

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 __________________ 35

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 0 _______________ 13, 24, 35

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296_________________ 35

Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U. S.

457_____________________ _________________________ 46

Clark v. Kansas City, 176 U. S. 114__________________ 16

Continental Baking Co. v. Woodring, 286 U. S. 352 __13,16

Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540 _____ 15

Cory v. Carter, 48 Ind. 337 __________________________ 44

Cummings v. Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528______36, 39

Dawson v. Lee, 83 Ky. 4 9 ____________________________ 44

Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265____________ 13,16

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147________________________ 43

PAGE

Gong Lum v. Kice, 275 U. S. 78___________________36,41,42

Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. v. Grosjean, 301 U. S.

412 _____________________________________________13,16

Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464__________________ 13,17

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496_______________________ 18

Hamilton v. Board of Regents, 293 U. S. 245__________ 40

Hartzel v. United States, 322 IT. S. 68Q________________ 18

Henderson v. United States, Oct. Term 1949, No. 25____ 37

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 8 1 ____13, 31, 32, 34

Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333

U. S. 203 ________________________________________ 21

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214________ 31, 33, 34

Kotch v. Board of River Port Pilot Commissioners, 330

U. S. 552 _______________________________________ 13,17

IV

PAGE

Lehew v. Brummell, 103 Mo. 546-------------------------------- 44

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444------------------------------------- 48

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501---------------------------------- 30

Maxwell v. Bugbee, 250 TJ. S. 525------------------------- 13,15,16

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 II. S. 266-------------- 14,17

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294

U. S. 580 ________________________________________ 16

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337— 36, 42, 54

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373------------------------------ 35, 37

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 IT. S. 536---------------------------------- 32

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Bussell, 216 U. S. 290 ---- 2

Oyama v. California, 332 TJ. S. 633 ----------------------------- 33

Patsone v. Pennsylvania, 232 U. S. 138---------------------- 16

People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438 ----------------------------- 44

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ------------ 36, 37, 39, 42, 43,

44, 45,46,48, 50, 53

Puget Sound Power & Light Co. v. Seattle, 291 U. S.

619 ______________________________________________ 16

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 TJ. S. 389— 14,17

Queenside Hills Co. v. Saxl, 328 U. S. 8 0 -------------------13,16

Boberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849)------44, 45, 50

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147-------------------------------- 18

Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U. S. 118-------------- 18

Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393 --------------------------------34, 45

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ---------------------- 13,15, 33, 35

Sipuel v. Board of Begents, 332 U. S. 631 ------------ 22, 43, 54

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 TJ. S. 535 ------------------------- 14,17

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553 --------------------------------14,17

Southern Bailway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400------14,15,17

State, Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 210--------------- 44, 50

Steele v. Louisville & N. B. Co., 323 U. S. 192------------13, 32

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ------------ 15, 34, 45

Sweatt v. Painter, et al., October Term, 1949, No. 44.___23,46

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 334 U. S. 410 33

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 --------------------------- 35

Truax v. Baich, 239 TJ. S. 3 3 ----------------------------------- 14,17

V

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 IT. S. 210 ----------------------------------- 33

United States v. American Trucking Assn., 310 U. S.

534 ______________________________________________ 46

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U. S. 144 30

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36 __________________________ 44

West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624 ____________________________________ 30

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 -------------- ----------- 18,35

Statutes

70 Oklahoma Statutes, 1941, Sections 455, 456, 457 ------7,10

Title 28, United States Code, Sec. 2281 ---------------------- 2

United States Code, Title 8, Secs. 41, 4 3 -------------------10,11

Other Authorities

American Jurisprudence, Volume 47—Schools, Sec. 6— 19

American Teachers Assn., The Black & White of Re

jections for Military Service (1944) ---------------------- 23

Baruch, Glass House of Prejudice (1946) _ _ --------------- 28

Bond, Education of the Negro in the American Social

Order, 3 (1934) _________________ ________________ 26

Bunche, Education in Black and White, 5 Journal of

Negro Education 351 (1936) -------------------- 26

Clark, Negro Children, Educational Research Bulletin

(1923)___________________________ 23

Cooper, The Frustrations of Being a Member of a

Minority Group: What Hoes It Do to the Individual

and to His Relationships With Other Peoplef 29

Mental Hygiene 189 (1945) ----------------------------------- 26

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1865)--------------------- 49

Cong. Grlobe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866)______________ 47

Cong. Grlobe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1872)----------------- 45, 50

Cong. Globe, 43rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1874)-------- 20,45,49, 50

Cong. Rec., 43rd Cong., 1st Sess. (1874)---------------------51, 53

PAGE

VI

Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of En

forced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science

Opinion, 26 Journal of Psychology 259 (1948)--------- 26

Dollard, Caste and Color in a Southern Town (1937)__ 26

Douglas, Stare Decisis, 49 Col. L. Eev. 735 (1949)_____ 39

Education for Freedom, Inc., A Symposium, of Radio

Broadcasts on Education in a Democracy (1943)___ 19

Fairman & Morrison, Does the Fourteenth Amendment

Incorporate the Bill of Rights?, 2 Stanford L. Eev.

5 (1949) ________________________________________ 48

Faris, The Nature of Human Nature (1937)__________ 25

Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1908) _______________________________________ 47

Frankfurter, Some Reflections on the Reading of Stat

utes, 47 Col. L. Eev. 527 (1947)___________________ 54

Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1949)______25, 30

Gallagher, American Caste and the Negro College

(1938) ___________________________________________ 28

Hamilton & Braden, The Special Competence of the

Supreme Court, 50 Yale L. J. 1319 (1941)__________ 30

Henderson, The Plight of the Private College and

What to do About It, The Educational Eecord

(October, 1949) 18

Henrich, The Psychology of Suppressed People (1937) 26

James, The Philosophy of William James, 128 (1925)__ 28

Johnson, Patterns of Segregation, II, Behavioral Re

sponse of Negroes to Segregation and Discrimina

tion (1943) _____________________________________ 25,26

Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration

(1935) _____________ ..._____________________________ 23

Klineberg, Race Differences (1935) __________________ 23

LaFarge, The Race Question and the Negro (1945)____ 28

Lasker, Race Attitudes in Children (1949)___________ 25

Loescher, The Protestant Church and the Negro (1948) 28

Long, Psychogenic Hazards of Segregated Education

of Negroes, 4 The Journal of Negro Education 343

(1935) _________________________________________ 25,26

PAGE

V l l

Lusky, Minority Rights and the Public Interest, 52 Yale

L. J. 1 (1942) ____________________________________ 17

Mannheim, K., Diagnosis of Our Times (1944)_______ 20

Mangum, Jr., The Legal Status of the Negro (1947)___ 26

McLean, Psychodynamic Factors in Racial Relations,

244 Annals of the American Academy of Political

and Social Science, 159, 161 (March, 1946)________ 26

McWilliams, Race Discrimination and the Law, 9

Science and Society No. 1 (1945)__________________ 26

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth—The Fallacy

of Race (1945) ___________________________________ 23

Morgan, Horace Mann, His Ideas and Ideals (1936)___ 19

Moton, What the Negro Thinks (1929)_______________25,26

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) __________ 25, 26, 27

Park, The Basis of Prejudice, The American Negro, the

Annals, Yol. 140 _________________________________ 25

Peterson & Lanier, Studies in the Comparative Abili

ties of Whites and Negroes, Mental Measurement

Monograph (1929) _______________________________ 23

Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,

To Secure These Rights (1947) ________________ 26

Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Edu

cation, Higher Education for American Democracy,

Vol. 1 (1947) ___________________________________ 21,26

Report of National Committee on Segregation in the

Nation’s Capital, Segregation in Washington (Nov.,

1948) _____------_____---------------------------------------------------- 28

Rose, America Divided: Minority Group Relations in

the United States (1948) _________________________ 23

Smythe, The Concept of “ Jim Crow” , 27 Social Forces

48 (1948) _______________________________________ 27

Testimony of R. Redfield in Sweatt v. Painter, October

Term, 1949, No. 4 4 _______________________________ 23

Thompson, Mis-Education for Americans, 36 Survey

Graphic, 119 (1947) ______________________________ 28

Thompson, Separate But Not Equal, The Sweatt Case,

33 Southwest Review 105 (1948) ________________ 30

PAGE

vm

Tussman & ten Broek, The Equal Protection of the

Laws, 37 Cal. L. Rev. 341 (1949) ____________ 16, 30, 46

Ware, The Role of the Schools in Education for Racial

Understanding, 12 Journal of Negro Education 421

(1944) ___________________________________________25, 28

Young, America’s Minority Peoples (1932) __________ 26

Notes

36 Col. L. Rev. 283 (1936) ___________________________ 30

40 Col. L. Rev. 531 (1940) _______ -___________________ 30

49 Col. L. Rev. 629 (1949) __________________________ 46

46 Mick. L. Rev. 639 (1948) _________________________ 29

41 Yale L. J. 1051 (1931) ___________________________ 30

56 Yale L. J. 1051 (1947) ___________________________ 26

Editorial Note, 19 Journal of Negro Education 4 (1949) 30

PAGE

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1949

No. 34

G. W . M cL aurin ,

Appellant,

vs.

Oklahoma S tate R egents for H igher

E ducation, B oard of R egents of U ni

versity of Oklahoma, et al.

appeal from the district court of the united states

FOR T H E W ESTE R N DISTRICT OF O K L A H O M A

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT.

Opinion Below.

No opinion was filed by the court below. Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law were filed at the close of the

first hearing (R. 31-34). Journal entry of Judgment for

this hearing was filed October 6, 1948 (R. 34-35). At the

close of the hearing on appellant’s motion to modify the

order and judgment (R. 35-38), Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Lawr and Judgment were entered on November

22, 1948 (R. 39-44).

2

Statement of Jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdic

tion to review this cause on appeal under the provisions

of Title 28, United States Code, Section 1253, this being an

appeal from an order denying, after notice and hearing, an

injunction in a civil action required by an act of Congress

to be heard and determined by a district court of three

judges for the reason that in this action plaintiff-appellant

sought to enjoin the enforcement of statutes of the State

of Oklahoma,1 and to enjoin the enforcement of an order

made by an administrative board acting under state

statutes.2

The District Court for the Wetsern District of Okla

homa sitting as a specially constituted three-judge court

rendered a final judgment in this cause sustaining* the

validity of an order made by an administrative board acting

under statutes of the State of Oklahoma after the validity

of state statutes and the order had been placed in issue by

the appellant on the ground that they were repugnant to

the Constitution of the United States.

Application for appeal was presented on January 18,

1949 (E. 45) and was allowed on the same day (E. 108).

Probable jurisdiction was noted by this Court on November

7, 1949 (E. 111).

1 Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281.

2 Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281; See: Oklahoma

Natural Gas Co. v. Russell, 261 U. S. 290.

3

The State Statutes and Administrative Order, the

Validity of Which Is Involved.

The Oklahoma Statutes, the validity of which are in

volved are Sections 455, 456 and 457 of Title 70 of the Okla

homa Statutes (1941) which provide in part as follows:

70 0. S. 1941, Section 455, makes it a misdemeanor,

punishable by a fine of not less than $100 nor more than

$500 for

“ any person, corporation or association of persons

to maintain or operate any college, school or insti

tution of this State where persons of both white and

colored races are received as pupils for instruction, ’ ’

and provides that each day same is to be maintained or

operated “ shall be deemed a separate offense” .

70 0. S. 1941, Section 456, makes it a misdemeanor,

punishable by a fine of not less than $10 nor more than $50

for any instructor to teach

“ in any school, college or institution where members

of the white race and colored race are received and

enrolled as pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day such an instructor shall continue

to so teach “ shall he considered a separate offense” .

70 O. S. 1941, Section 457, makes it a misdemeanor

punishable by a fine of not less than $5 nor more than $20

for

“ any white person to attend any school, college or

institution, where colored persons are received as

pupils for instruction,”

and provides that each day such a person so attends “ shall

be deemed a distinct and separate offense” ,

4

After the hearing and judgment in this case the Okla

homa Legislature repealed these statutes and enacted simi

lar statutes which contained the following proviso:

“ * * * that the provisions of this Section shall not

apply to programs of instruction leading to a par

ticular degree given at State owned or operated col

leges or institutions of higher education of this State

established for and/or used by the white race, where

such programs of instruction leading to a particular

degree are not given at colleges or institutions of

higher education of this State established for and/or

used by the colored race; provided further, that said

programs of instruction leading to a particular de

gree shall be given at such colleges or institutions of

higher education upon a segregated basis. Segre

gated basis is defined in this Act as classroom in

struction given in separate classrooms, or at sepa

rate times.”

These statutes are set out in full in the Appendix.

At the hearing for a preliminary injunction the Court

held that “ insofar as any statute or law of the State of

Oklahoma denies or deprives this plaintiff admission to the

University of Oklahoma for the purpose of pursuing the

courses of study he seeks, it is unconstitutional and unen

forceable” . The Court, however, refused to issue prelim

inary injunction (E. 34).3

3 “ The court is of the opinion that insofar as any statute or law

of the State of Oklahoma denies or deprives this plaintiff admission

to the University of Oklahoma for the purpose of pursuing the course

of study he seeks, it is unconstitutional and unenforceable. This does

not mean, however, that the segregation laws of Oklahoma are in

capable of constitutional enforcement. W e simply hold that insofar

as they are sought to be enforced in this particular case, they are

inoperative” (R . 33).

5

Order by Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma,

a State Board, Acting Pursuant to State Statutes, the

Validity of Which Is Involved.

Subsequent to the above order of the Court and the filing

of a motion for further relief by the plaintiff, the defendant

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma acting as a

state board pursuant to the statutes of Oklahoma adopted

an order which appears in the minutes of said board as

follows:

‘ ‘ That the Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma authorize and direct the President of the

University, and the appropriate officials of the Uni

versity, to grant the application for admission to the

Graduate College of G. W. McLaurin in time for Mr.

McLaurin to enrol at the beginning of the term,

under such rules and regulations as to segregation

as the President of the University shall consider to

afford to Mr. G. W. McLaurin substantially equal

educational opportunities as are afforded to other

persons seeking the same education in the Graduate

College, and that the President of the University

promulgate such regulations” (R. 97).

In refusing to enjoin the enforcement of this order the

Court held as a matter of Jaw that: “ The Oklahoma stat

utes held unenforceable in the previous order of this Court

have not been stripped of their validity to express the public

policy of the State in respect to matters of social con

cern * * * ” (R. 42).

The Court refused to enjoin the enforcement of either

the statutes or the order, dismissed the complaint of the

plaintiff, and rendered judgment for the defendants (R.

43-44).

6

Statement of the Case.

On the 5th day of August, 1948, appellant filed in the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Oklahoma a complaint required to he heard and determined

by a three-judge court as provided by the then existing

Section 266 of the Judicial Code seeking a preliminary and

permanent injunction against the Oklahoma State Regents

for Higher Education, the Board of Regents of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma and the administrative officers of the

University of Oklahoma enjoining them from enforcing

Sections 455-457 of the Oklahoma statutes of 1941 under

which the plaintiff and other qualified Negro applicants

were excluded from admission to the courses of study of

fered only at the Graduate School of the University of

Oklahoma.

The complaint alleged that the appellant, G. W. Mc-

Laurin, was qualified in all respects for admission to the

Graduate School of the University of Oklahoma but was

denied admission solely because of race or color pursuant

to the statutes of the State of Oklahoma and the orders of

the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma acting

pursuant to said statutes. Motion was made for a pre

liminary injunction. A hearing was held on the motion

for preliminary injunction upon an agreed statement of

facts in which all of the material facts were admitted and

agreed upon. It was admitted that appellant, McLaurin,

was qualified in all respects other than race or color for

admission to the University of Oklahoma and that the

courses he desired were offered by the State of Oklahoma

only at the University of Oklahoma (R. 20-21).

On the 6th day of October, 1948, the three-judge court

filed a journal entry which said in part: “ it is ordered and

7

decreed that insofar as Sections 455, 456 and 457, 70 0. S.

1941, are sought to be applied and enforced in this par

ticular case, they are unconstitutional and unenforceable” .

The Court, however, refrained from granting any injunc

tive relief but retained jurisdiction of the subject matter for

entering any further orders as might be deemed proper

(E. 34-35).

On the 7th day of October, 1948, appellant filed a motion

for further relief alleging that despite the prior ruling of

the court, appellant had again been denied admission to the

Graduate School of the University of Oklahoma and re

quested that the court enter an order requiring appellees

to admit appellant to the “ graduate school of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma for the purpose of taking courses leading

to a doctor’s degree in education, subject only to the same

rules and regulations which apply to other students in said

school” (E. 38).

At the hearing on the motion for further relief it ap

peared that the appellant has been admitted to the Graduate

School of the University of Oklahoma but on a segregated

basis. At this hearing counsel for both parties agreed in

open court as to the essential facts.4

Judge Murkah summed up the agreement as to essential

facts as follows:

‘ ‘ Judge Murrah: The 13th of October admitted to

the University of Oklahoma and to the courses which

he sought to pursue in his application to the Uni

versity proper officials on January 28, 1948, that he

was admitted to the same classes that other students

pursuing these courses, under the same instructors,

and that he was assigned a permanent desk or chair

4 It has been the policy of the lower court to secure agreements

between counsel rather than to use testimony insofar as possible

(R. 53).

8

in an anteroom to title main classroom where other

students were seated, that the Exhibits 1 to 5, which

have been introduced into evidence, fairly represent

the physical conditions under which he was admitted,

and where he now sits and now pursues his course of

study.

“ It is further admitted that he can from this

position see the instructor and hear the lecture, that

he can see all or most of his fellow students, and

that he is not obstructed in listening to the lecture

or pursuing his course, except under conditions

which may be hereinafter discussed.

* * * * * *

“ Now it is further agreed that he is admitted to

the library at the University of Oklahoma where all

other students are admitted and on the same condi

tions, except that he is assigned a permanent desk

on the landing above the second floor of the library,

and that he is required by the administrative

rules to occupy this desk while using the library,

and in so doing he is required to leave his desk,

go to the librarian, I suppose, and get the books

he wishes, take them to his desk and use them there,

while other students pursuing the same courses and

using this library, go into the library, select the

books they wish and take them home or any place

that they may wish to pursue their studies” (E. 56).5

It was admitted that Negroes constitute the only group

which is segregated in the University of Oklahoma (E. 63-

64) and McLaurin testified as to the conditions of segre

gation to which he had been subjected and the effect of such

segregation upon him as a student (E. 58-63).

5 The exhibits referred to appear in the Record on pages 92-96.

The order of the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma

of October 10, 1948 which required the maintenance of rules and

regulations as to segregation in the admission of the appellant appears

in the Record at page 97.

9

The issue in the second hearing was clearly set forth in

the motion for further relief (E. 35-38) and during the hear

ing (E, 50).

On the 22d day of November, 1948, the three-judge court

issued Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Journal

Entry. In the Conclusions of Law, the Court held:

1. That the United States Constitution “ does not au

thorize us to obliterate social or racial distinctions which

the State has traditionally recognized as a basis for classi

fication for purposes of education and other public min

istrations. The Fourteenth Amendment does not abolish

distinctions based upon race or color, nor was it intended

to enforce social equality between classes and races” .

2. “ It is the duty of this court to honor the public policy

of the State in matters relating to its internal social affairs

quite as much as is our duty to vindicate the supreme law

of the land.”

3. “ The Oklahoma statutes held unenforceable in the

previous order of this court have not been stripped of their

vitality to express the public policy of the State in respect

to matters of social concern.”

4. “ We conclude therefore that the classification, based

upon racial distinctions, as recognized and enforced by the

regulations of the University of Oklahoma, rests upon a

reasonable basis, having its foundation in the public policy

of the State, and does not therefore operate to deprive this

plaintiff of the equal protection of the laws” (E. 41-42).

The journal entry denied the relief prayed for, dis

missed the complaint and entered judgment for the appel

lees (E. 44).

Subsequent to the hearing and judgment in the lower

court, appellant, McLaurin, was permitted to go into the

10

regular classroom and to sit in a section surrounded by a

rail on which there was a large sign stating “ Reserved for

Colored” . At the beginning of the last semester, February,

1950, the rail and sign were removed. Appellant is now per

mitted to eat in the students’ cafeteria but is required to

sit at a segregated table. He is permitted to use the main

library but only on a segregated basis.

Question Presented.

The Statement as to jurisdiction heretofore filed in this

Court presented the following question:

Whether in providing graduate education in a state

university the state may exclude a Negro student from the

classroom and require him to participate in classes through

an open doorway maintaining a spacial separation from

other students?

Errors Relied Upon.

The District Court erred:

1. In refusing to enjoin the defendants as state officers

from enforcing Sections 455, 456 and 457 of the Oklahoma

Statutes of 1941 upon the ground that the enforcement of

said statutes violated the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and Title 8, Sections 41 and 43 of the

United States Code.

2. In refusing to enjoin the defendants as state officers

from enforcing the order of defendant Board of Regents of

the University of Oklahoma requiring the segregation of

plaintiff from all other students of the University of Okla

homa solely because of race or color upon the ground that

said order is a violation of the equal protection and due

11

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States and Title 8, Sections 41 and 43

of the United States Code.

3. In ruling as a matter of law that the claim of the

plaintiff to an education in a state institution on a non-

segregated basis without distinction as to race or color was

not a constitutional right but a mere matter of public policy

of the State in regard to its internal social affairs.

4. In ruling as a matter of law that the plaintiff’s right

to public education without racial distinction, segregation

or ostracism by the State of Oklahoma was a matter of the

internal social affairs of the State of Oklahoma controlled

solely by the public policy of the State and was not a right

protected by the Constitution of the United States.

5. In ruling as a matter of law that the Oklahoma

Statutes previously held by the Court to be unconstitutional

and unenforceable could nevertheless be used as a consti

tutional basis for subsequent orders of the defendants to

segregate plaintiff from all other students and thereby

ostracize him solely because of race and color.

6. In ruling as a matter of law that state statutes previ

ously declared unconstitutional as applied to plaintiff by

state officers could be applied as a source of public policy

to authorize the segregation of plaintiff from all other

students of the University of Oklahoma solely because of

race or color.

7. In ruling as a matter of law that the order requiring

the segregation of plaintiff from the other students solely

because of race or color rested “ upon a reasonable basis

and did not deprive the plaintiff of the equal protection of

the laws or the right to liberty as guaranteed by the Con

stitution ’ ’.

12

8. In ruling as a matter of law, in the absence of any

evidence whatsoever to establish reasonableness of the

classification, that the order requiring the segregation of

the plaintiff from all other students solely because of race

or color was a classification which rested upon a reason

able basis and did not violate the due process or equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

9. In ruling as a matter of law that the Fourteenth

Amendment does not prohibit the State of Oklahoma from

making racial distinctions among its citizens in the per

formance of its governmental function of providing public

education at the graduate school level.

Summary of Argument.

The first hearing in this case involved the validity of

the statutes of the State of Oklahoma which required com

plete exclusion of appellant from the University of Okla

homa solely because of race and color. The second hearing

involved the enforcement of an order of the Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma requiring the segre

gation of appellant within the University of Oklahoma.

Both of the hearings involved the refusal of the appellees to

permit the appellant to attend classes at the University of

Oklahoma subject only to the same rules and regulations

which apply to other students similarly situated.

In this case the obvious purpose of racial segregation in

public education is made clearer than in any other case

presented to this Court. To admit appellant and then single

him out solely because of his race and to require him to sit

outside the regular classroom could be for no purpose other

than to humiliate and degrade him—to place a badge of

inferiority upon him. His admission destroyed whatever

13

reason or policy which, might have theretofore existed for

requiring white and Negro students to attend separate

institutions.

This case involves the efforts of the appellant, a Negro,

to obtain graduate education at the University of Oklahoma

subject only to the same rules and regulations which apply

to other students in said school” (R. 38). He has been

denied that right because of his race and color; “ simply

that, and nothing more” . This the Constitution forbids.

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of their an

cestry are by their very nature odious to a free people

whose institutions are founded upon the doctrine of equal

ity. For that reason, legislative classification or discrimi

nation based on race alone has often been held to be a denial

of equal protection.” '6 “ Discriminations based on race

alone are obviously irrelevant and invidious” ,7 and there

fore arbitrary and unreasonable. Their imposition upon

any citizen by any agency of government is reconcilable

neither with due process of law8 nor with the equal pro

tection of the laws.9

This Court, while recognizing the right of the state to

make reasonable classifications, has consistently held that

such classifications must be based upon some real or sub

stantial difference in relation to a legitimate legislative

end which has pertinence to the statute’s objective.10 The

6 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100.

7 Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 323 U. S. 192,

203.

8 Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 82.

9 Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

10 Dominion Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265 ; Maxwell v. Bugbee,

350 U. S. 525; Continental Baking Co. v. Woodring, 286 U. S. 352;

Great Atlantic Tea Co. v. Grojean, 301 U. S. 412; Queenside Hills Co.

v. Saxl, 328 U. S. 80; Kotch v. Board River Port Pilot Commissioner,

330 U. S. 552; Groessart v. Cleary, 335 U. S. 464,

14

State of Oklahoma has shown neither a real nor substantial

difference nor the pertinence of alleged racial differences

to graduate education. Where alleged differences on which

a classification is based do not in fact exist, or cannot be

reasonably or rationally related to the legislative objec

tives, the classification violates the equal protection clause.11

However, the lower court in this case considered that it

was under a duty “ to honor the public policy of the state

in matters relating to its internal social affairs quite as

much as it is our duty to vindicate the supreme law of the

land” (E. 42). The relief was then denied on the ground

that: “ We conclude therefore that the classification, based

upon racial distinctions, as recognized and enforced by the

regulations of the University of Oklahoma, rests upon a

reasonable basis, having its foundation in the public policy

of the State and does not therefore operate to deprive this

plaintiff of the equal protection of the laws” (E. 42).

This decision is in direct conflict with the prior decisions

of this Court with respect to the power of a state to classify

in general as well as its prohibitions against governmentally

imposed racial classifications.

The appellees rely solely upon the asserted validity of

the separate but equal doctrine which they have extended to

graduate education. This doctrine should be subjected to

critical analysis and if found to be applicable to graduate

education should be rejected by this Court as being in direct

conflict with the intent and purpose of the Fourteenth

Amendment and other decisions of this Court.

11 Quaker City Cab Co v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389; Southern

R. R. Co. v. Greene, 216 U .S. 400; Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 33;

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553; Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297

U. S. 266; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535.

15

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The exclusion of appellant from the regular class

room and the requirement of spacial segregation solely

because of race and color is in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment.

The appellant herein having been admitted to the

Graduate School of the University of Oklahoma, pursuant

to an order of the court below, was thereupon compelled

by the appellees to physically separate himself from the

other students in his classroom solely because of his race

and color. He was further required by appellees to physi

cally segregate himself in the use of library facilities and

in the students’ cafeteria solely because he is a colored per

son of Negro ancestry. The appellees, in compelling appel

lant to take advantage of a course of study and physical

facilities in perceptible isolation, solely because of his race

and color, have effected a classification, the basis of which

is clearly repugnant to constitutional guarantees of equal

protection.

The basic purpose and intent of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was to prohibit a state

from denying to its Negro citizens any rights given by the

state to its white citizens. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. 8. 303; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1. Another pur

pose was to insure that all persons similarly situated would

receive like treatment and that no special groups or classes

be singled out for favorable or discriminatory treatment,

Southern Railway v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400; Connolly v.

Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540; Maxwell v. Bugbee,

250 U. 8. 525.

16

The secondary purpose is broader in scope than the

first since it is not primarily concerned with racial distinc

tions but with discrimination generally. In determining

whether state legislation subserves the second purpose, this

Court has not prohibited all, hut only certain types of legis

lative distinctions. On the other hand, racial classifications

for governmental action are subjected to a more rigid test.

The racial classification in this case meets neither test.

A. The limitation on a state’s right to classify for legisla

tive purposes.

This Court in interpreting the scope of equal protection

has long recognized and approved the necessity for legisla

tive classification as an indispensable concomitant of orderly

government. Bain Peanut Co. v. Pinson, 282 U. S. 499.

It has upheld reasonable classification even though in

cidental discrimination was an inevitable result. Metropoli

tan Ins. Co. v. Brownell, 294 U. S. 580 ; Puget Sound Power

and Light Co. v. Seattle, 291 U. S. 619; Board of Tax Com

missioners v. Jackson, 283 U. S. 527; Patsone v. Penn, 232

U. S. 138; Clark v. Kansas City, 176 U. S. 114. But this

Court has not, even in approving such classification, given

sanction without examination and scrutiny.12 This Court

has, in accordance with this procedure applied the familiar

general test of constitutionality applicable to these cases,

i. e., a test which requires that the legislative classification

he found to be based upon some real or substantial differ

ences between classes which are relevant to the legitimate

legislative end which is the object of the statute. Dominion

Hotel v. Arizona, 249 U. S. 265; Maxwell v. Bughee, supra;

Continental Baking Co. v. Woodring, 286 U. S. 353; Great

Atlantic Tea Co. v. Grojean, 301 IT. S. 412; Queenside Hills

12 Tussman & ten Broek, The Equal Protection of the Laws, 37

Calif. Law Review 341 (1949).

17

Co. v. Saxl, 328 U. S. 80; Kotch v. Board River Port Pilot

Commissioner, 330 U. S. 552; Groessart v. Cleary, 335 IT. S.

464. If the differences are not reasonably perceptible, or

are not relevant to the legislative end, the classification vio

lates that which the equal protection clause secures. Quaker

City Cab. Co. v. Penn, 277 IT. S. 389; Southern RR. Co. v.

Greene, 216 IT. S. 400; Truax v. Raich, 239 IT. S. 33; Smith

v. CaJioon, 283 IT. S. 553; Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck,

297 IT. S. 266; Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535.

This formula has been consistently followed by this

Court without deviation since the adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment as the most effective method of giving

life and substance to the equal protection clause while at

the same time leaving to the states freedom to deal with

problems of everyday government.

In this case Oklahoma has singled out one group of its

citizens to be segregated from all other citizens in the en

joyment of governmental facilities. This is not a case of

voluntary separation on the part of either the Negro or

non-Negro students, it is governmentally imposed segrega

tion. Such a classification must either meet the test set out

above or be declared unconstitutional. To test the con

stitutionality of this classification we must examine the

objective Oklahoma is attempting to accomplish in offering

educational facilities for graduate education and determine

what relevance, if any, race, ancestry or skin pigmentation

may have to such objective.

The Objectives of Public Education.

As a way of life, we are dedicated to a system which

places reliance upon rational persuasion rather than upon

force and coercion.18 It is our belief that given a choice, 13

13 For a discussion of differences between ours and a totalitarian

system and discussion of national interest in elimination of racial

discrimination see: Lusky, Minority Rights and the Public Interest,

52 Yale Law Journal 1 (1942).

18

our citizenry will choose the rational and wise. Lovell v.

Griffin, 303 U. S. 444; Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147;

Hague v. C. 1. 0., 307 U. S. 496. Mr. Justice Brandeis, in a

concurring opinion in Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357,

375, stated this basic philosophy succinctly when he said:

“ Those who won our independence believed that

the final end of the State was to make men free to

develop their faculties; that in its government the

deliberative forces should prevail over the arbi

trary. ’ ’ 14

For that reason, our society is dedicated to the fullest

personal and political freedom of the individual. In order

to make certain that our citizens are equipped to make

rational decisions and thus maintain and preserve our dem

ocratic institutions, it is vital that through the medium of

education their individual skills, values, belief in the basic

tenets of democracy be developed. So important has this

become that education is no longer left solely to the parent

or to a few philanthropists.15 It has become one of the

14 Cf. Schneiderman v. United States, 320 U. S. 118, 120 (1943):

“ While it is our high duty to carry out the will of Congress,

in the performance of this duty we should have a jealous regard

for the rights of petitioner. W e should let our judgment be guided

so far as the law permits by the spirit of freedom and tolerance

in which our nation was founded, and by the desire to secure the

blessings of liberty in thought and action to all those upon whom

the right of American citizenship has been conferred by statute,

as well as to the native born. And we certainly should presume

that Congress was motivated by these lofty principles.”

See also: Baumgartner v. U. S., 322 U. S. 665; Hartzel v. U. S.,

322 U. S. 680.

15 “ The Plight of the Private Colleges and What to do About

it” by Algo D. Henderson, October, 1949 issue of The Educational

Record, published by the American Council on Education.

19

highest functions of state government.16 Thus, the forty-

eight states have almost uniformly undertaken the func

tion of providing educational benefits at a minimum cost

to all in order that they might endeavor to develop the

fullest intellectual and moral qualities and to thereby in

sure the most effective participation in the responsibility

and duties of citizenship.

Horace Mann described the purpose of education in a

democratic society as follows: 17

‘ ‘ Education must be universal # * # The theory

of our government is—not that all men, however

unfit, shall be voters—but that every man, by the

power of reason and the sense of duty, shall become

fit to be a voter. Education must bring the practice

as nearly as possible to the theory. As the children

now are, so will the sovereigns soon be. How can we

expect the fabric of the government to stand, if vic

ious materials are daily wrought into its framework.

Education must prepare our citizens to become mu

nicipal officers, intelligent jurors, honest witnesses,

legislators, or competent judges of legislation—in

fine, to fill all the manifold relations of life. For

this end, it must be universal. ’ ’

Mortimer J. Adler, professor of law at the University

of Chicago, states the purpose in these terms.18

‘ ‘ Liberal education is developed only when a cur

riculum can be devised which is the same for all men,

16 At common law, the parent’s control over his child extended

to education of the child. The parent’s common law rights and duties

in this regard “ have been generally supplemented by constitutional

and statutory provisions, and it is now recognized that education is a

function of the government” . 47 Am. Jur. Schools, Section 6, page

299.

17 Horace Mann— His Ideas and Ideals by Joy Elmer Morgan,

Natl. Home Foundation, Washington, D. C., 1936, page 98.

18 Education for Freedom, a Series of Radio Lectures, sponsored

and published by the Education for Freedom, Inc., New York: 1943.

Other lectures by Mark Van Doren and Dr. Robert M. Hutchins,

among others, also included pertinent remarks on this subject.

20

and should be given to all men, because it consists

in those moral and intellectual disciplines which lib

erate men by cultivating their specially rational

power to judge freely and to exercise free will. * * *

‘ ‘ * * * Only when all young men and women are

prepared by liberal education for the responsibili

ties of citizenship, and the obligations of the moral

and intellectual life, will the world community come

into existence. Without it world peace is impos

sible. ’ ’

Education is not only a component part of true dem

ocratic living, but is the very essence of and medium

through which democracy can be effected. The intent of

the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment was indicated

in the 43rd Congress in 1874 by these words: “ * * * that

all classes should have the equal protection of American

law and be protected in their inalienable rights, those rights

which grow out of the very nature of society, and the or

ganic law of this country.” 19 In 1943, an eminent soci

ologist and economist, Dr. Karl Mannheim, then Professor

of Economics at London School of Economics, said:

“ Finally, there is a move towards a true democ

racy arising from dissatisfaction with the infinite

simal contribution guaranteed by universal suffrage,

a democracy which through careful decentralization

of functions allots a creative social task to everyone.

The same fundamental democratization claims for

everyone a share in real education, one which no

longer seeks primarily to satisfy the craving for so

cial distinction, but enables us adequately to under

stand the pattern of life in which we are called upon

to live and act. ’ ’ 19 20

19 Congressional Globe, Forty-third Congress, May 22, 1874.

20 Mannheim, Karl, “ Diagnosis of Our Time” , Oxford University

Press, 1944, page 177.

21

Finally, in 1947, seventy-three years after the 43rd Con

gress, the President’s Committee on Higher Education took

an unequivocal position against segregation in education.

In terms of a definition of the role played by education the

Report said:

“ * * * the role of education in a democratic society

is at once to insure equal liberty and equal oppor

tunity to differing individuals and groups, and to

enable the citizens to understand, appraise, and re

direct forces, men, and events as these tend to

strengthen or to weaken their liberties.” 21

Mr. Justice F rankfurter stated in Illinois ex rel. Mc

Collum v. Board of Education, 333 U. S. 203, 216, 217:

“ The sharp confinement of the public schools to

secular education was a recognition of the need of a

democratic society to educate its children, insofar as

the State undertook to do so, in an atmosphere free

from pressures in a realm in which pressures are

most resisted and where conflicts are most easily and

most bitterly engendered. Designed to serve as per

haps the most powerful agency for promoting co

hesion among a heterogeneous democratic people, the

public school must keep scrupulously free from en

tanglement in the strife of sects.”

It is, therefore, evident that the objective of public edu

cation is to equip our citizens with information and skills in

order that they may effectively participate in our demo

cratic processes. Public education is no longer a privilege of

the few. It is no longer a minor function of government.

It is one of the most important of governmental functions.

21 Report of the President’s Commission on Higher Education,

Higher Education for American Democracy, Govt. Printing Office,

Washington, 1947, Vol. I, page 5.

22

Neither Race, Ancestry Nor Skin Pigmentation of

Students Has Any Pertinence to the Objectives

of Public Education.

The requirement of spacial segregation in education in

Oklahoma is based solely on race or color, ‘ ‘ simply that

and nothing more.” Solely because appellant is a Negro

he has been denied rights enjoyed as a matter of course by

all other qualified students.22 Appellant’s individual rights

are lost in the racial group classification.

Appellees have so far made no effort to show any rele

vancy between compulsory racial segregation and the law

ful objectives of public education. On the other hand, it is

evident that the State of Oklahoma, while professing equal

ity within a segregated system, has in fact consistently

maintained the objective of inequality insofar as Negroes

are concerned. Prior to 1948, Negroes -were completely ex

cluded from graduate and professional training.23 After

the decision in the Sipuel case the appellees continued the

exclusion of Negroes from graduate and professional

schools. The conditions under which appellant was admitted

after the first order in this case was a continuation of the

same policy of inequality.

The practice of racial segregation has sometimes been

rationalized by the claim that there are inherent differences

between the races. This essential racist view assumes that

minorities belong to inferior races, and that racial inter

mixture results in the degeneracy of the superior race.

After an exhaustive study of all scientific data referring to

22 Counsel for all parties agreed that: “ the only group of citizens

attending the University of Oklahoma who are segregated are

Negroes’’ (R . 63).

23 Sipuel v. Board of Regents, et al., 332 U. S. 631.

23

the intellectual capacity of different racial groups, an ex

pert witness testified in another pending case to this effect:

“ The conclusion then, is that differences in intel

lectual capacity or inability to learn have not been

shown to exist as between Negroes and whites, and

further, that the results make it very probable that

if such differences are later shown, to exist, they will

not prove to be significant for any educational policy

or practice. ’ ’ 24

One of the leading sociologists in the field of race rela

tions has pointed out: “ there is not one shred of scientific

evidence for the belief that some races are biologically su

perior to others, even though large numbers of efforts have

been made to find such evidence.” 25 There is no rational

basis, no factual justification for segregation in education

on the grounds of race or color. The racist premise is com

pletely invalid, and no act of segregation based upon it can

be upheld as reasonable.26

24 Testimony of Dr. Robert Redfield in Sweatt v. Painter, et al.,

October Term, 1949, No. 44.

25 Rose, Arnold M., America Divided: Minority Group Relations

In the United States, published by Knopf, New York City, 1948.

28 Otto Klineberg, Race Differences, page 343, 1935; Montague,

M. F. A., Man’s Most Dangerous Myth— The Fallacy of Race,

Columbia University Press, New York, 1945, page 188, “ The Black

and White of Rejections for Military Service” , American Teachers

Association, August, 1944, page 29; Otto Klineberg, Negro Intelli

gence and Selective Migration, New York, 1935; J. Peterson & L. H.

Lanier, Studies in the Comparative Abilities of Whites and Negroes,

Mental Measurement Monograph, 1929; W . W . Clark, Negro Chil

dren, Educational Research Bulletin, Los Angeles, 1923.

24

Compulsory Racial Segregation in Public Educa

tion Is an Arbitrary and Unlawful Classification

W ithin the General Limitations Upon Right o f

States to Classify Its Citizens.

This Court had no hesitancy in striking down compul

sory residential segregation predicated upon racial the

ories :

“ It is the purpose of such enactments, and it is

frankly avowed it will be their ultimate effect, to

require by law at least in residential districts, the

compulsory separation of the races on account of

color. Such action is said to he essential to the

maintenance of the purity of the races, although it

is to be noted in the ordinance under consideration

that the employment of colored servants in white

families is permitted, and nearby residences of col

ored persons not coming within the blocks, as defined

in the ordinance, are not prohibited.” 27

State ordained segregation having no rational founda

tion is a particularly invidious policy which needlessly

penalizes Negroes, demoralizes others, and tends to destroy

democratic institutions. I f the racial factor has no scien

tific basis, then the ills suffered as a result of racial segre

gation in graduate education are doubly harmful. We have

pointed out above the purposes and objectives of educa

tion. In light of those objectives, segregation is an abortive

factor to the full realization of the objective of education.

First, segregation prevents both the Negro and white

student from obtaining a full knowledge and understanding

of the group from which he is separated, thereby infringing

upon the inherent rights of an enlightened citizen. It has

been scientifically established that no child at birth pos

27Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 81; see also: Shelley v.

Kraemer, supra.

25

sesses either an instinct or even a propensity towards

feelings of prejudice or superiority. These attitudes, when

and if they do appear, are but reflections of the attitudes

and institutional ideas evidenced by the adults about him.28

The very act of segregation tends to crystallize and per

petuate group isolation, and serves, therefore, as a breeding

ground for unhealthy attitudes.29

Secondly, a feeling of distrust for the minority group

is fostered in the community at large, a psychological

atmosphere which is most unfavorable to the acquisition of

a proper education. Still another result of segregation in

education with respect to the general community is that it

accentuates imagined differences between Negroes and

others.30

The uncontradicted testimony of the appellant in this

case shows the effect of racial segregation upon him in his

effort to obtain an education (R. 58-63). As a matter of

fact, the effect on McLaurin is the inevitable result of com

pulsory segregation and there is a corresponding harmful

28 Robert E. Park, The Basis of Prejudice, The American Negro,

the Annals, Vol. 140, pages 11-20 as cited in The Negro in the United

States by E. Franklin Frazier, McMillan Co., New York, 1949, page

668; Elsworth Faris, The chapter on “ The Natural History of Race

Prejudice” , from The Nature of Human Nature, New York, 1937,

page 354.

29 Bruno Lasker, Race Attitudes in Children, New York, 1949,

page 48; Caroline F. Ware, “ The Role of the Schools in Education

for Racial Understanding” , 12 Journal of Negro Education No. 3,

pp. 421-431 (1944 ); Robert R. Moton, What the Negro Thinks

(Garden City, N. Y., 1929), page 13; Howard Hale Long, “ Psycho

genic Hazards of Segregated Education of Negroes” , The Journal

of Negro Education, Vol. IV, No. 3, July, 1935, page 343; see also:

Charles S. Johnson, Patterns of Segregation (1943), Pt. II, “ Be

havioral Response of Negroes to Segregation and Discrimination” .

30 As stated by Gunnar Myrdal in An American Dilemma, New

York, 1944, Vol. 1, page 625: “ But they are isolated from the main

body of whites, and mutual ignorance helps reinforce segregative

attitudes and other forms of race prejudice.”

26

effect on the non-segregated group and society in general.

Deutsclier and Cliein, The Psychological Effect of Enforced

Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion, 26 Journ.

of Psychology 259 (1948); Cooper, The Frustrations of

Being a Member of a Minority Group: What Does It Do

to the Individual and to His Relationships With Other

Peoplef 29 Mental Hygiene 189 (1945); McLean, Psycho

dynamic Factors in Racial Relations, 244 Annals of the

American Academy of Political and Social Science 159, 161

(March, 1946).

Qualified educators, social scientists, and other experts

have uniformly expressed their realization of the fact that

‘ ‘ separate ’ ’ is irreconciliable with ‘ 4 equality ’ ’ .S1 There can

be no equality since the very fact of segregation establishes

a feeling of humiliation and deprivation to the group con

sidered to be inferior.32

Probably the most irrevocable and deleterious effect of

segregation upon the minority group is that it imposes a

81 Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma, New York, 1944, Vol.

1, page 580; Charles S. Johnson, Patterns of Segregation, New York,

1943, page 4, 318; Charles S. Mangum, Jr., The Legal Status of the

Negro, Chapel Hill, 1940; Report of the President’s Committee on

Civil Rights, “ To Secure These Rights” , Government Printing Office,

Washington, 1947; Report of the President’s Commission on Higher

Education, “ Higher Education for American Democracy” , Vol. I,

Government Printing Office, Washington, 1947. Max Deutscher and

Isidor Chein (with the assistance of Natalie Sadigur), “ The Psycho

logical Effects of Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science

Opinion” . The Journal of Psychology, 1948, 26, 259-287.

82 Carey McWilliams, “ Race Discrimination and the Law” ,

Science and Society, Vol. IX , No. 1, 1945: 56 Yale Law, 1947, pages

1051-1052, 1059; Bond, “ Education of the Negro in the American

Social Order” , 1934, page 385; Moton, “ What the Negro Thinks” ,

1922, page 99; Bunche, “ Education in Black and White” , 5 Journal

of Negro Education, 1936, page 351; Long, “ Some Psycho-Genic

Hazards of Segregated Education of Negroes” , 4 Journal of Negro

Education, 1935, pages 336-343; Henrich, “ The Psychology of Sup

pressed People” , 1937, page 52; Dollard, “ Caste and Color in a

Southern Town” , 1937, pages 269, 441; Young, “ America’s Minority

Peoples” , 1932, page 585.

27

badge of inferiority upon the segregated group.33 34 This

badge of inferior status is recognized not only by the

minority group, but by society at large. As Myrdal has

pointed out:

“ Segregation and discrimination have had ma

terial and moral effects on whites, too. Booker T.

Washington’s famous remark that the white man

could not hold the Negro in the gutter without getting

in there himself, has been corroborated by many

white southern and northern observers. Throughout

this book, we have been forced to notice the low

economic, political, legal and moral standards of

Southern whites-—kept low because of obsession with

the Negro problem. Even the ambition of Southern

whites is stifled partly because, without rising far,

it is so easy to remain ‘ superior’ to the held-down

Negroes.” 84

A definitive study of the scientific works of contempo

rary sociologists, historians and anthropologists conclu

sively document the proposition that the intent and result

of segregation are the establishment of an inferiority status.

And a necessary corollary to the establishment of this value

33 Hugh H. Smythe, “ The Concept of ‘Jim Crow’ ” , Social Forces,

Vol. 27, No. 1, Oct., 1948, page 48: “ ‘Jim Crow’ as used in a

sociological context thus indicates for a specific social group the

Negro’s awareness of his badge of inequality which he learns through

the operation of a ‘Jim Crow’ concept in his every day living. This

pattern of existence has become so much a part of the nation’s social

structure that it has become synonymous with the words ‘segrega

tion’ and ‘discrimination’, and at times when ‘Jim Crow’ is indexed

some authors have indexed it as a cross reference for these terms.”

34 Gunnar Myrdal, op. cit., Vol. I, page 644.

28

judgment is the deprivation suffered by both the minority

and majority groups.35

35 Baruch, Glass House of Prejudice, William Morrow and Co.,

1946, pages 66-76, Gallagher, Buell G., American Caste and the

Negro College, Columbia University Press, 1938, page 94:

“ Wherever possible, the caste line is to keep all Negroes below the

level of the lowest whites. This is the first and deepest meaning

of ‘separate but equal’ ” . Page 105: “ Not the least important aspect

of the caste system is its results in seriously malconditioning the

individuals whose psychological growth is strongly affected by a

caste divided society. These influences are not limited to the Negro

caste. They stamp themselves upon the dominant caste as well” ;

LaFarge, John, The Race Question and the Negro, New York,

Longmans Green & Co., 1945, page 159: “ Segregation, as a com

pulsory measure based on race, imputes essential inferiority to the

segregated group. Segregation, since it creates a ghetto, brings in

the majority of instances, for the segregated group, a diminished de

gree of participation in those matters which are ordinary human

rights, such as proper housing, educational facilities, police protection,

legal justice, employment, * * * Hence it works objective injustice.

So normal is the result for the individual that the result is rightly

termed inevitable for the group at large” ; James, “ The Philosophy

of William James” , 1925, page 128: “ Properly speaking, a man has

as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and

carry an image of him in their mind. To wound any one of these

images is to wound him” ; Loescher, Frank S., “ The Protestant

Church and the Negro” , Association Press, 1948. “ (Segregation)

is, in itself, an implication of inferiority, an inferiority not only of

status but of essence, of being” ; Thompson, “ Mis-education for

Americans” , Survey Graphic, Vol. 36, Jan., 1947, page 119: “ Edu

cation for segregation, if it is to be effective, must perpetuate beliefs

which define the Negro’s status as inferior, which emphasize super

ficial differences, or which in any way suggest that the Negro is a

lower order of being and therefore should not be expected to be

treated like a white person” . Page 120: “ Mis-education for segre

gation has deleterious effects on both Negroes and whites. It re

quires mental and emotional gymnastics on both sides to adjust (or

attempt to adjust) to the many logical and ethical contradictions of

segregation. The situation is crippling to the personalities of both

Negro and white Americans” ; Ware, “ The Role of the Schools in

Education for Racial Understanding” , 12 Journal of Negro Educa

tion, 421 (1944), page 424: “ A segregated school system presents

almost insuperable obstacles. In such a system the social situations

may be made worse by vicious attitudes, or uplifted by sympathetic

ones. But the sheer fact of segregation stands as an eternal reminder

to every white child, every day, that the Negro or Mexican children

are being kept away from his school” ; Segregation in Washington,

A Report of the National Committee on Segregation in the Nation’s

Capital, November, 1948, pages 76, 77.

29

There is no compensatory value to society as a result

of the ills suffered from segregation. As we have pointed

out above, segregation in education has produced delete

rious effects upon both the majority and minority groups.

We have similarly found that the only logical premise upon

which segregation could be based—i. e., the existence of

differences in intellectual ability as between the races—has

been completely discredited by scientific studies. It would

appear then, that the only remaining rationale for segre

gation is that although it might be admitted that racial

segregation has no validity, the prevailing customs and

mores require that segregation be broken down in a grad

ual manner.36 However, all available data which refers to

instances where segregation did exist but was subsequently

broken down, controvert this assumption.

The experiences of states with a racial and social policy

similar to that of Oklahoma demonstrate that this policy

may be abandoned at least at the graduate and professional

level to the advantage of all concerned. The University of

Maryland has admitted Negroes into its law school since

1935. Negroes have freely attended the University of

West Virginia since 1939. The University of Arkansas

in 1947 admitted a Negro to its law school on a segregated

basis. Before the term had ended, it had abandoned the

segregation, and now Negroes are attending its law school

and School of Medicine just like any other students. The

University of Delaware was opened to Negroes, as is the

University of Kentucky. In September, 1949, a Negro was

admitted into the University of Texas School of Medicine.

In all instances there was considerable initial resistance by

governmental officials to the abandonment of segregation.

36 See Note 46 Mich. L. Rev. 639 (1948).

30

Yet in each instance the experiment has been beneficial and

successful.37 38

In the absence of any scientific basis for enforced racial

segregation, there can be no relationship between alleged

racial differences and the lawful objectives of public edu

cation. Applying the recognized standard for measuring

the constitutionality of general classifications it is clear

that the classification in this case fails to meet that standard.

B. Classifications by governmental agencies based solely

on race or ancestry are particularly odious to our prin

ciples o f equality.

The compulsory racial segregation in this ease not only

fails to meet the test as to general state classifications but it

is also in direct conflict with the special test as to racial

and religions classifications. As to those matters which

are not usually the subject of state regulation because spe

cifically prohibited by the federal constitution, this Court

has required the application of another and more stringent

examination into constitutionality, i. e., there must be a

conclusive showing of actual differences and pertinence

must be justified.88 United States v. Carotene Products Co.,

37 Editorial Note, Journal of Negro Education, December, 1949,

pages 5-6. See also: Charles H. Thompson, Separate But Not Equal,

The Sweatt Case, 33 Southwest Review, 105, 111 (1948). Frazier,

The History of the Negro in the United States (1950), chap. 17.

38 It is sometimes said that where the governmental action is based

upon race or color, there is presumption of unconstitutionality. See

Tussman and ten Broek, op. cit. supra footnote 12; Note, 36 Col. L.

Rev. 283 (1936 ); 40 Col. L. Rev. 531 (1940); 41 Yale L. J. (1931);

Hamilton & Broden, The Special Competence of the Supreme Court,

50 Yale L. J. 1319; 1349-1357 (1941). This appears to be similar to

the Court’s placement of freedom of speech, press, assembly and re

ligion in a preferred position. See, e. g., Marsh v. Alabama, 326

U. S. 501, 508; W est Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,

319 U. S. 624, 739.

31

304 U. S. 144, note 4; Hirabayashi v. United States, 320

U. S. 81. This Court has allowed invasion of this latter

area only when an overwhelming public necessity was

clearly shown to exist. Korematsu v. United States, 323

U. S. 214; Hirabayashi v. United States, supra. In the

absence of an overwhelming public necessity, this Court

has never allowed governmental regulation of this consti

tutionally prefererd area and has nullified all such unrea

sonable and irrational classifications.

The end sought herein by the Oklahoma legislature and

the appellee is the higher education of its citizens. It is now

well established that a state in providing higher educa

tion for its citizenry must afford equal protection and equal

opportunity to all under constraint of the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore what, rel

evancy race has to the objective sought and what are the

real differences between appellant and his classmates which

justify the classification here made are the questions to

which this Court would ordinarily seek answers. In this

instance, however, it is entirely unnecessary to seek an

answer, for the appellees admit that appellant’s race is

the only difference between appellant and his classmates

and they have never contended that race has any relevancy

to higher education. The usual inquiry into these matters is

thus eliminated and the question involved is reduced to an

inquiry as to whether race or color alone may be made the

basis of a classification by the state.

This Court has said that race or color may not, in view

of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, be made the basis of classification by the state.

Distinctions among citizens under eontraint of state power

which are based solely upon the race or color of such citi

zens have incurred such constitutional odium that they are

32

presumptively void. This Court has, in recent decisions,

vigorously disparaged and censored them.

In Hirabayashi v. United States, supra, Mr, Justice

S tone speaking for the Court said at 100:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odius to a

free people whose institutions are founded upon the

doctrine of equality. For that reason, legislative

classification or discrimination based on race alone

has often been held to be a denial of equal pro

tection. ’ ’

Mr. Justice M orphy concurring at page 110, said:

“ Distinctions based on color and ancestry are

utterly inconsistent with our traditions and ideals.”

In Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536, Mr. Justice H olmes