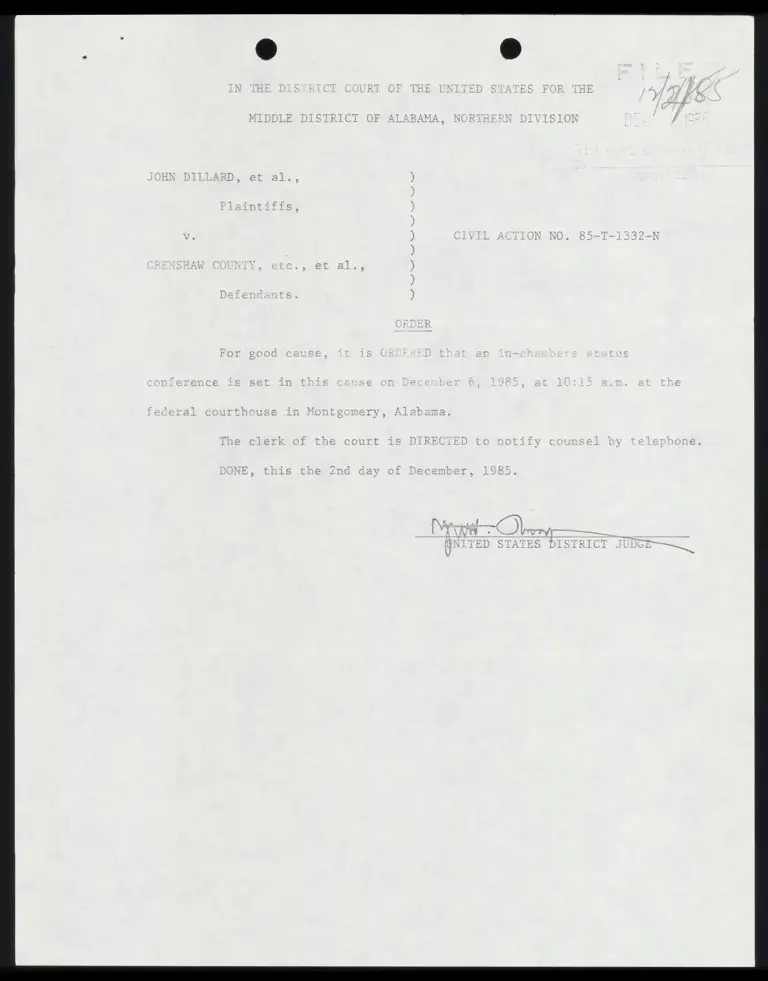

Order RE: In-Chambers Status Conference

Public Court Documents

December 12, 1985

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Order RE: In-Chambers Status Conference, 1985. 54d3ca10-b9d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/afcead45-2311-4a3e-aa55-5326ba9d975a/order-re-in-chambers-status-conference. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

P.O. BOX 711

MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 36101

OFFICIAL BUSINESS

PENALTY FOR PRIVATE USE $300

Hon. Deborah Fins

Hon. Julius Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

1900 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

POSTAGE AND FEES P,

UNITED STATES COUN

USC 42

LU Jah FF JV