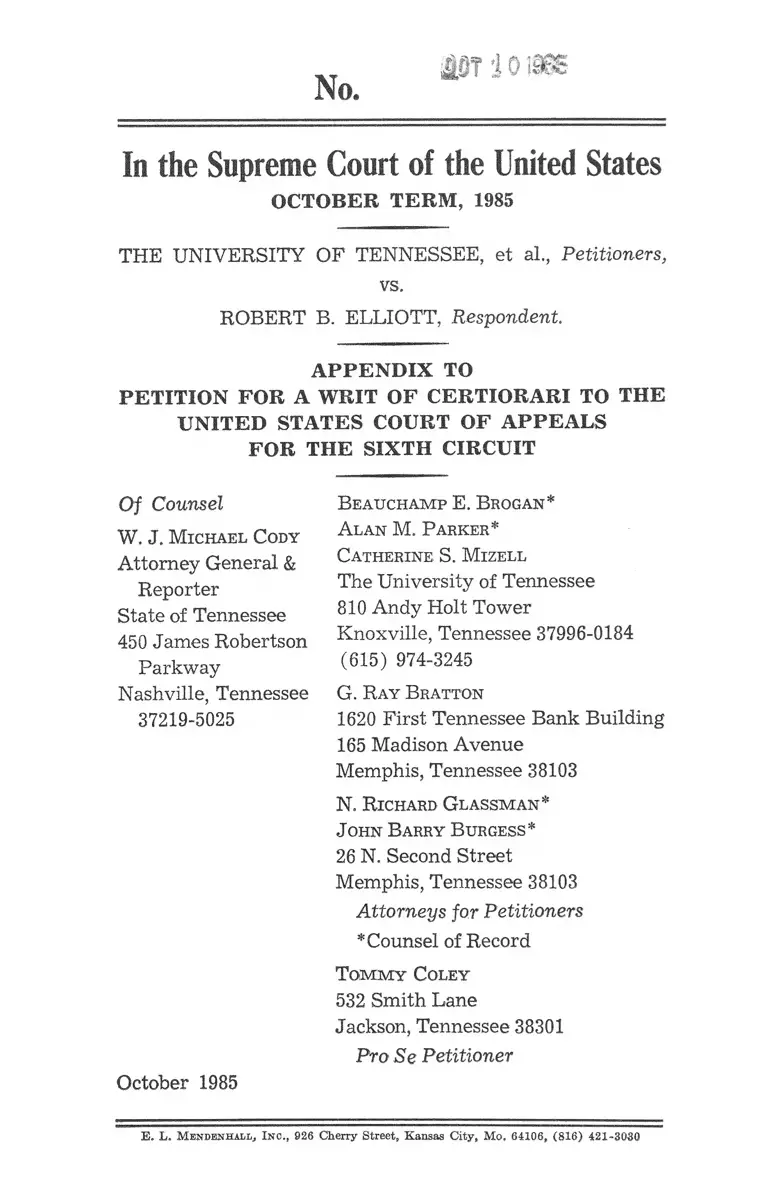

University of Tennessee v. Elliott Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of Tennessee v. Elliott Appendix to Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 425e82f2-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b05f99da-c4ca-4dc3-a76d-3e290e623b45/university-of-tennessee-v-elliott-appendix-to-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

i o im No.

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM , 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al., Petitioners,

vs,

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT, Respondent.

APPE N D IX TO

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Of Counsel

W. J. M ichael C ody

Attorney General &

Reporter

State of Tennessee

450 James Robertson

Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee

37219-5025

B eaucham p E. B rogan*

A lan M. P arker*

Catherine S, M izell

The University of Tennessee

810 Andy Holt Tower

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-0184

(615) 974-3245

G. R ay B ratton

1620 First Tennessee Bank Building

165 Madison Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

N. R ichard G la ssm a n *

J ohn B arry B urgess*

26 N. Second Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

T o m m y Coley

532 Smith Lane

Jackson, Tennessee 38301

Pro Se Petitioner

October 1985

E . L . M endenhall, Inc., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, M o. 64106, (816) 421-3030

TABLE OF CONTENTS

OPINION OF THE COURT OF APPEALS ............. A1

OPINION OF THE DISTRICT COURT _____________A26

FINAL AGENCY ORDER ............ ..... ........... .................A33

INITIAL ORDER OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

JUDGE ........................................................ ..... ............ A3 6

JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEALS ........... A183

OPINION IN Buckhalter v. Pepsi-Cola Bottlers, Inc.,

768 F.2d 842 (7th Cir. 1985) ...... ................ ....... ....... A185

A1

No. 84-5692

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On A ppeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Tennessee

Decided and Filed July 9, 1985

Before: K eith and M artin, Circuit Judges; and

Edwards, Senior Circuit Judge.

B oyce F. M artin, Jr., Circuit Judge. Robert B. Elliott

appeals from an order of the district court granting sum

mary judgment to the defendants on his claim that the

defendants violated his civil rights.

Elliott is a minority employee of the University of

Tennessee Agricultural Extension Service. He has been

employed by the Service since 1966. On December 18,

1981, the Dean of the Service advised Elliott that he was

to be terminated from his job due to inadequate work

performance, inadequate job behavior, and incidents of

gross misconduct. On December 22, 1981, Elliott filed an

A2

administrative appeal from the Notice of Pending Ter

mination under the Tennessee Uniform Administrative

Procedure Act. On January 5, 1982, Elliott filed his fed

eral complaint that forms the basis of the present appeal.

Elliott’s federal complaint alleges that in the past

he made complaints to University of Tennessee officials

regarding racial discrimination in the treatment of black

leaders, students, and staff personnel in connection with

4-H club events and a series of racially derogatory acts

on the part of University officials. One of Elliott’s major

complaints was a racial slur made by defendant Coley,

a Service livestock judge, at an official Service event.

The federal complaint alleges that following Elliott’s

complaint regarding the Coley incident, defendants

Downen, Luck, and Shearon (University officials) con

spired with defendants Murray Truck Lines and Korwin

to have Elliott terminated from his job. Elliott recently

had complained to Korwin, shop manager at Murray Truck

Lines, regarding eight racially insulting signs in windows

at Murray Truck Lines’ place of business. The complaint

alleges that the University officials conspired with Korwin

to secure a letter from Korwin accusing Elliott of referring

to Mr, Murray as a “ white racist” and threatening him.

Based on the Korwin letter, Downen placed a letter of

reprimand in Elliott’s job file.

The complaint also alleges that, because of Elliott’s

complaint regarding Coley, the University officials con

spired with defendants Donnell, Johnson, Smith, Hopper,

and Cathey, all of whom were members of the Agricultural

Extension Service Committee in the county in which Elliott

was employed, to have the Committee recommend to

Downen that Elliott be terminated from his job. Two

black members of the Committee refused to vote for

A3

Elliott’s removal. All five white members, two of whom

are related to Coley by marriage, voted for Elliott’s re

moval.

The complaint next alleges that Elliott’s immediate

Supervisor, Shearon, and other University officials began

a harassment campaign by requiring Elliott to produce

mileage books when white employees were not subject

to the same requirement; unjustifiably finding fault with

his work; subjecting him to discriminatory job assign

ments; attempting to place pretextual supervisory com

plaints in his personnel file; and falsely accusing him of

failure to carry out a specific job assignment.

The complaint alleges that at least one of the individual

defendants was aware that Elliott was active in a federal

lawsuit seeking to secure the right of blacks to gain mem

bership in exclusively white country clubs in Gibson and

Madison County, Tennessee, and that the present defen

dants’ actions were designed in part to punish him for

his efforts in that case.

Finally, the complaint alleges that the Service con

tinues to discriminate against black citizens by refusing

to implement an effective affirmative action plan; failing

to integrate its homemaker demonstration clubs and other

educational activities; refusing to integrate its 4-H clubs;

refusing to address low minority participation in agricul

tural programs and community resource development pro

grams; refusing to eliminate discrimination in promotion,

training, and continuing education; refusing to eliminate

discrimination in the establishment and operation of agri

cultural extension committees; and permitting discrimina

tion by local white officials against black participants in

educational programs.

A4

The complaint seeks certification of a class of “persons

in Tennessee who are similarly situated [as Elliott] and/or

affected by the policies . . . complained of herein which

violate not only the rights of [Service employees] . . .

but also the rights of black infant and adult citizens who

are intended beneficiaries of [the Service] . . . The

relief requested includes an injunction restraining the

University of Tennessee, the Service, the University offi

cials, and the Committee from continuing the discrim

inatory practices outlined above. Also requested is a

preliminary and permanent injunction requiring defen

dants to cease attempting to discharge, cause the discharge

of, or otherwise penalize Elliott on the basis of false alle

gations and other harassing actions. Finally, the complaint

seeks attorneys’ fees and one million dollars in damages.

The complaint invokes jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331

and 1341. Claims are asserted under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983, 1985, 1986, 1988, 2000d and e and under the first,

thirteenth, and fourteenth amendments.

On January 19, 1982, the court entered a temporary

restraining order prohibiting the defendants from taking

any personnel action against Elliott. On February 23,

1982, the court withdrew the restraining order to permit

the parties to proceed through the state administrative

appeals process. The court emphasized that the with

drawal of the restraining order did not “ in any fashion

adjudicate] the merits of this controversy.”

After dissolution of the restraining order, the parties

proceeded through the Tennessee administrative review

process. The contested case provisions of the Tennessee

Code provide for determination of the issues by an admin

istrative judge who must be an employee of the affected

agency or of the office of the secretary of state. Tenn.

Code Ann. § 4-5-102(1) & (4). A party may move to

A5

disqualify an administrative judge for “bias, prejudice,

or interest,” Tenn. Code Ann, § 4-5-302(a), the adminis

trative judge may not be a person who has been involved

in the investigation or prosecution of the case, Tenn. Code

Ann. § 4-5-303(a), and the administrative judge may

not receive ex parte communications, Tenn. Code Ann.

§ 4-5-304(a). The parties have the right to be represented

by counsel, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-305 (b), to receive

notice of the hearing, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-307(a), to

file pleadings, motions, briefs, and proposed findings of

fact and conclusions of law, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-308 (a)

& (b), to request the administrative judge to issue sub

poenas, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-311 (a), and to examine

and cross-examine witnesses, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-312

(b). The administrative judge is bound by the civil

rules of evidence except that evidence otherwise not

admissible may be relied upon if it is “of a type com

monly relied upon by reasonably prudent [people] in

the conduct of their affairs.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-313

(1). An order issued by an administrative judge must

include conclusions of law and findings of fact. Tenn.

Code Ann. § 4-5-314 (c). An initial appeal from an ad

verse decision by the administrative judge is to the agency

itself or to a person designated by the agency. Tenn.

Code Ann. § 4-5-315(a). Judicial review of the final

agency decision may be had by filing a petition for review

in the state chancery court within sixty days of entry

of the agency’s order. Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (b).

The chancery court sits without a jury and is limited

to a review of the administrative record to determine

whether the agency decision is in violation of constitu

tional or statutory provisions or is arbitrary, capricious,

or unsupported by substantial evidence. Tenn. Code Ann.

§ 4-5-322 (g) & (h). Review of the decision of the chan

cery court may be had in the Court of Appeals of Ten

nessee. Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-323.

A6

The administrative judge conducted a lengthy hearing

in which Elliott’s counsel examined nearly one hundred

witnesses. The University alleged eight separate instances

of poor job performance and sought approval of its de

cision to dismiss Elliott. Elliott defended against the

charges by asserting, inter alia, that the accusations against

him were racially motivated. The administrative judge

issued an order upholding four of the eight charges but

denying approval of the dismissal. Instead, the order di

rected that Elliott retain his position but be transferred

to a different county. The decision of the administrative

judge concluded that he had no jurisdiction to hear El

liott’s claims of civil rights violations. Nevertheless, the

claims of racial discrimination were considered “ affirma

tive defenses” to the University’s charges, and the ad

ministrative judge made the following finding:

An overall and thorough review of the entire evidence

of record leads me to believe that employer’s action

in bringing charges against employee . . . [was] based

on what it, through its administrative officers and su

pervisors perceived as improper and/or inadequate

behavior and inadequate job performance rather than

racial discrimination. I therefore conclude that em

ployee has failed in his burden of proof to the claim

of racial discrimination as a defense to the charges

against him.

Elliott appealed this decision to the University of Ten

nessee Vice President for Agriculture, who concluded that

the University’s actions were not racially motivated and

rejected the appeal. Neither Elliott nor the University

filed a petition for review in the state courts.

Eighty-four days after entry of the administrative or

der, Elliott renewed action on his pending federal com

A7

plaint. Elliott filed a motion for a temporary restraining

order to prevent the defendants from transferring Elliott

to a different county or, to the extent that Elliott already

had been transferred, to restore him to his previous location.

Specifically, the motion requested a restraining order be

cause

said decision of the Administrative Law Judge and the

agency constituted an abuse of discretion, is contrary

to law, and is not supported by reliable, probative, and

substantive evidence. Said Administrative Law Judge

and agency have demonstrated their unwillingness

and/or inability to determine objectively and imparti

ally the constitutional [and federal statutory claims]

raised by the Plaintiff in his Complaint and therefore,

said decision should be stayed until this Court can

make a preliminary determination of the likelihood

[of success on the merits] since only this Court can

exercise the Article III powers which are peculiarly

applicable to those constitutional and Federal claims.

The motion further particularly alleged that the “Admin

istrative Law Judge’s and Agency’s decision and remedy

was . . . unconstitutional and unlawful in wrongfully re

jecting said claims of racial discrimination by plaintiff

despite clear evidence thereof.”

The University of Tennessee opposed the motion for

a restraining order and also filed a motion for summary

judgment on the underlying complaint. Its memorandum

in opposition to Elliott’s motion and its motion for sum

mary judgment asserted the same principles. The Uni

versity claimed that the district court lacked jurisdiction

to “ review the merits” of the final agency order because

by state statute review may be had only in the Tennessee

chancery courts and only on timely petition for review.

A8

The University also asserted that principles of res judicata1

prevented “relitigation” of the claims of racial discrimina

tion in federal court.

Elliott responded to the motion for summary judgment

by arguing that to dismiss his federal claims in deference

to the final agency order would be to “effectively confer

Article III power upon an Administrative Law Judge who

is an agent for the U.T. defendants in this case.” Elliott

concluded that the “ Court has absolutely no basis upon

which an award of summary judgment to defendants can

be predicated.”

On May 12, 1984, the district court granted the Uni

versity’s motion for summary judgment. The court adopted

the two grounds of decision urged by the University. Al

though only the University had moved for summary judg

ment, the court granted summary judgment in favor of all

defendants. Elliott then perfected this appeal.

We will assume, for the sake of argument, that Elliott’s

motion for a temporary restraining order may plausibly be

read as asking the court to “review the merits” of the

agency order and that Tennessee’s procedural prerequisites

somehow prevented a federal court from granting the re

1.

Res judicata encompasses two forms of preclusion, claim pre

clusion under which “ final judgment on the merits _ of an

action precludes the parties or their privies from relitigating

issues that were or could have been raised in that action,”

Federated Department Stores, Inc. v. Moitie, 452 U.S. 394,

398, 101 S.Ct. 2424, 2427, 69 L.Ed.2d 103 (1981), Restatement

(Second) of Judgments § 24 (1982), and issue preclusion,

under which a decision precludes relitigation of the same

issue on a different cause of action between the same parties

once a court decides an issue of fact or law necessary to its

judgment.

Duncan v. Peck, 752 F.2d 1135, 1138 (6th Cir. 1985). Throughout

this opinion, we will intend “res judicata” and “rules of preclusion”

to refer to principles of both issue and claim preclusion.

A9

straining order. Making those assumptions, the most that

can be said is that the court should not have granted a

restraining order. That denial of relief, however, would

not affect the viability of Elliott’s underlying complaint.

Elliott’s complaint does not ask for “review” of a state

agency order. It asks for an injunction to prevent the de

fendants from discharging him or “ otherwise penalizing]

him pursuant to false allegations of inadequate job per

formance.” The complaint also seeks one million dollars

in damages. Elliott did not invoke the court’s jurisdiction

under the administrative review provisions of the Tennessee

Code. He unambiguously invoked the jurisdiction of the

federal courts pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331 and 1343 and as

serted claims under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986,

1988, 2000d and e and under the first, thirteenth, and

fourteenth amendments.2

Because Elliott’s complaint does not ask for “review”

of the agency order but does ask for a de novo federal

determination that arguably could undermine the validity

of the state order, the court correctly noted that an issue

of res judicata arises. The court’s analysis of the res

judicata issue consisted of the following:

2. The University’s argument regarding the effect of the

Tennessee review provisions may plausibly be read as an implicit

articulation of the argument that the existence of a state remedy

precludes resort to section 1983. That argument was rejected

by the Supreme Court more than twenty years ago. See Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961); see also Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840 (1976) (Title VII plaintiff who has pursued ad

ministrative remedies is entitled to trial de novo in federal

court; Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982) (exhaustion

of state administrative remedies is not a prerequisite to main

tenance of a section 1983 action). Justice Frankfurter’s dissent

in Monroe took issue with the majority’s principle, but his view

has been resuscitated, in a constitutionalized form, only in the

area of procedural due process. See Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S.

527 (1981); Hudson v. Palmer, ...... U.S.......... , 104 S. Ct. 3194

(1984); see also Wagner v. Higgins, 754 F.2d 186, 193 (6th Cir.

1985) (Contie, J., concurring) (Parratt does not apply to viola

tion of substantive constitutional rights).

A10

This Court is convinced that the civil rights statutes

set forth in Title 42 of the United States Code

. . . were not intended to afford the plaintiff a means

of relitigating what plaintiff has heretofore litigated

over a five-month period. Therefore, this Court should

dismiss the case upon the doctrine of res judicata.

Unfortunately, the parties failed to advise the court

of several cases which have rejected that position. In

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Co., 456 U.S. 461 (1982),

the Court considered the relationship between the guaran

tee of a trial de novo in Title VII actions3 and the prin

ciples of res judicata and federal-state comity as embodied

in 28 U.S.C. § 1738. The Court held:

No provision of Title VII requires claimants to pursue

in state court an unfavorable state administrative ac

tion. . . . While we have interpreted the “ civil action”

authorized to follow consideration by federal and state

administrative agencies to be a “ trial de novo,” Chan

dler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976), . . . neither

the statute nor our decisions indicate that the final

judgment of a state court is subject to redetermination

at such a trial.

Id. at 469-70 (emphasis in original). In a footnote that

accompanied this passage, the Court made explicit that

which was implicit in its emphasis on the phrase “final

judgment of a state court.”

3. The University makes the argument that “ this is not a

Title VII action” because, the University contends, Elliott’s federal

court complaint was untimely and he has not received a right

to sue letter. Elliott asserts that the complaint was timely and

that he has received a right to sue letter. For purposes of this

appeal, we must treat this action as a Title VII action because

the complaint unambiguously invokes Title VII and because the

district court made no finding or conclusion with respect to time

liness or Elliott’s receipt of a right to sue letter.

A l l

EEOC review of discrimination charges previously re

jected by state agencies would be pointless if the fed

eral courts were bound by such agency decisions. . . .

Nor is it plausible to suggest that Congress intended

federal courts to be bound further by state adminis

trative decisions than by decisions of the EEOC. Since

it is settled that decisions by the EEOC do not pre

clude a trial de novo in federal court, it is clear that

unreviewed administrative determinations by state

agencies also should not preclude such review even

if such a decision were to be afforded preclusive effect

in a state’s own courts.

Kremer, 456 U.S. at 470 n.7. The Court thus drew a

sharp distinction between state court judgments, which

are entitled to deference under the res judicata principles

of section 1738, and unreviewed state administrative deter

minations which are not. See also id. at 487 (Blackmun,

J., with Brennan & Marshall, JJ., dissenting) (recognizing

distinction made by majority); id. at 508-09 (Stevens, J.,

dissenting) (same). That is precisely the distinction that

this court drew in Cooper v. Philip Morris, Inc., 464 F.2d

9 (6th Cir. 1972), which was cited with approval by the

majority in Kremer.

The University recognizes, as it must, the general prin

ciple established by footnote 7 in Kremer. That principle,

however, is not to be applied, the University argues, when

the unreviewed administrative decision was rendered by

an agency that is authorized to grant full relief, such

as reinstatement and backpay, and that provides the liti

gants with elaborate adjudicative procedures. The Uni

versity finds support for this argument in two aspects

of the Kremer opinion. First, the University argues that

the Court in footnote 7 implicitly equated “state adminis

trative agency” with an agency that possesses powers sim

A12

ilar to those possessed by the federal Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, Because the Commission has

exclusively administrative rather than adjudicatory au

thority, the argument goes, the rule of non-preclusion an

nounced in footnote 7 may be applied only to the unre

viewed decisions of agencies that possess only administra

tive authority. Second, the University notes that in foot

note 26 of Kremer, the Court cites United States v. Utah

Construction & Mining Co., 384 U.S. 394 (1966), which

states that res judicata principles apply to the decision

of an administrative agency acting in “a judicial capacity.”

This citation is said to bolster the University’s proposed

distinction between the res judicata effect to be given

the decision of an agency acting in a judicial versus an

administrative capacity.

Both rationales for the University’s distinction are

without merit. First, the Kremer Court itself made plain

in footnote 7 that its rule of non-preclusion with respect

to unreviewed state administrative decisions applies to the

decisions of those agencies that have full enforcement au

thority and provide full adjudicative procedures as well

as to the decisions of agencies that lack those attributes.

The Court cited four lower court decisions in support

of the rule that it announced. Of those four cases, three

approved a rule of non-preclusion even though the state

agency had full enforcement authority and provided elab

orate adjudicative procedures. See Garner v. Giarrusso,

571 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1978); Batiste v. Furnco Construc

tion Corp., 503 F.2d 447 (7th Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420

U.S. 928 (1975); Cooper v. Philip Morris, Inc., 464 F'.2d

9 (6th Cir. 1972). The Court in Kremer certainly did

not have in mind, in footnote 7, the distinction urged

by the University.

The University is also unaided by footnote 26. The

context of the Court’s citation of Utah Construction makes

A13

evident that the Court did not intend to adopt the Uni

versity’s proposed distinction. The Court cited Utah Con

struction in the course of stating that the New York ad

ministrative procedure, in combination with state judicial

review of the administrative decision, did not offend due

process. Thus, the citation of Utah Construction was in

the context of a factual situation—a reviewed administra

tive decision—different from that implicated in the rule

of non-preclusion announced in footnote 7—-an unreviewed

administrative decision. The citation also was made in

the context of a legal issue—whether the procedures offend

due process—different from that implicated in footnote

7—whether res judicata should apply. Footnote 26 in

Kremer thus lends no support to the University’s argu

ment.

Finally, we note that in a post-Kremer Title VII deci

sion this Court refused to give preclusive effect to the

unreviewed decision of a state administrative agency that

possessed the attributes which the University argues should

exempt the agency from the dictates of Kremer. See

Smith v. United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners,

685 F.2d 164, 168 (6th Cir. 1982). No argument advanced

by the University has encouraged us to deviate from that

decision.

The district court’s holding that Elliott’s Title VII

claim is barred by res judicata must fall in light of the

unambiguous principle enunciated in Kremer. The more

difficult question is whether the court erred in dismissing

Elliott’s claims asserted under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983,

1985, 1986, and 1988. We conclude that the court erred

in dismissing those claims.4

4. Throughout the remainder of this opinion, we will refer

primarily to the claims asserted under section 1983. Our reason

ing and conclusion apply equally to the other statutory claims

asserted by Elliott.

A14

In Loudermill v. Cleveland Board of Education, 721

F.2d 550 (6th Cir. 1983), affd, ....... U.S. ....... , 105 S.

Ct. 1487 (1985), we held that an unreviewed state adminis

trative adjudication has no claim preclusive effect in a

subsequent section 1983 action in federal court. Id. at

559. In dictum, the Loudermill panel majority drew a

distinction between the claim preclusive effect and the

issue preclusive effect of a prior, unreviewed state ad

ministrative adjudication, stating that such an adjudication

should be accorded issue preclusive effect in section 1983

actions in federal court. See id. at 559 n.12. The court

cited United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co.,

384 U.S. 394 (1966), to support its view with respect to

issue preclusion.

Utah Construction does not support the broad principle

advanced in dictum in Loudermill. The Utah Construction

Court stated:

When an administrative agency is acting in a judicial

capacity and resolves disputed issues of fact properly

before it which the parties have had an adequate

opportunity to litigate, the courts have not hesitated

to apply res judicata to enforce repose.

384 U.S. at 422. This language certainly lends support

to the view advanced in Loudermill. That language, how

ever, must be read in its proper context. Utah Construc

tion involved the collateral estoppel effect to be given

a decision of the federal Advisory Board of Contract Ap

peals in a subsequent action in the Court of Claims. See

284 U.S. at 400. The Court did not address the deference

that federal courts should give to the unreviewed findings

A15

of state administrative agencies in subsequent federal civil

rights actions.®

The question whether a prior, unreviewed determina

tion of a state administrative agency must be given pre

clusive effect in a subsequent federal civil rights action

is a difficult issue that requires a careful analysis of Su

preme Court teachings. The starting point for this analysis

is Allen v. McCurry, 449 U.S. 90 (1980) and Migra v.

Warren City School District Board of Education,.... . U.S.

....... , 104 S. Ct. 892 (1984). These cases held that a federal

court adjudicating a section 1983 action must accord the

same preclusive effect to the decision of a state court

as the decision would be accorded by other courts of that

state. Neither Allen nor Migra, however, requires that

we give preclusive effect to the unreviewed findings of

a state administrative agency. Although Allen and Migra

recognized that the purpose of section 1983 was to provide

a civil rights claimant with a federal right in a federal

forum, the Court concluded that the legislative history

of section 1983 was not so unequivocal as to effect an 5

5. All of the cases the Court in Utah Construction cited in

support of its proposition involved the application of preclusion

principles to the prior determinations of federal agencies. See

Sunshine Anthracite Coal Co. v. Adkins, 310 U.S. 381 (1940)

(decision of the National Bituminous Coal Commission); Hanover

Bank v. United States, 285 F.2d 455 (Ct. Cl. 1961) (decision of

the Tax Court); Fairmont Aluminum Co. v. Commissioner, 222

F.2d 622 (4th Cir. 1955) (same); Seatrain Lines, Inc. v. Pennsyl

vania R. Co., 207 F.2d 255 (3d Cir. 1953) (decision of Interstate

Commerce Commission). The Court included a “see also” cite

to a diversity case that applied preclusion rules to the decision

of a private arbitration panel. See Goldstein v. Doft, 236 F.

Supp. 730 (S.D.N.Y. 1964), aff’d, 353 F.2d 484 (2d Cir. 1965),

cert, denied, 383 U.S. 960 (1966).

For the reasons noted earlier in this opinion, we do not

believe the Court at footnote 26 of Kremer v. Chemical Construc

tion Corp., 456 U.S. 461 (1982), meant to authorize the applica

tion of Utah Construction to the unreviewed decisions of a state

administrative agency when the claimant subsequently asserts

a federal right in a federal court.

A16

implied repeal of 28 U.S.C. § 1738 and the common law

rules of preclusion that section 1738 directed the federal

courts to respect. See Allen, 449 U.S. at 99; Migra, 104

S. Ct. at 897.

The conflict between section 1983 and section 1738

that the Court resolved in Allen and Migra is not present

when a federal court considers whether to give preclusive

effect to the unreviewed findings of a state administrative

agency. Section 1738 provides in relevant part:

Such Acts, records and judicial proceedings or copies

thereof, so authenticated, shall have the same full faith

and credit in every court within the United States

. . . as they have by law or usage in the courts

of such State . . . from which they are taken.

The “Acts, records and judicial proceedings” referred to

in the statute are the “Acts of the legislature of any

State” and the “records and judicial proceedings of any

court of any such State,” 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (emphasis

added). The statute does not require federal courts to

defer to the unreviewed findings of state administrative

agencies. See Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759

F.2d 355, 361 n.6 (4th Cir. 1985); Moore v. Bonner, 695

F.2d 799, 801 (4th Cir. 1982); see also Gargiul v. Tompkins,

704 F.2d 661, 667 (2d Cir. 1983), vacated on other grounds,

U.S.......... , 104 S. Ct. 1263, on remand, 739 F.2d 34

(1984) ;6 Patsy v. Florida International University, 634 F.2d

900, 910 (5th Cir. 1981) (en banc), rev’d on other grounds

sub nom. Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982);

Keyse v. California Texas Oil Corp., 590 F.2d 45, 47

n.l (2d Cir. 1978) (per curiam); Mauritz v. Schwind, 101

S.W.2d 1085, 1089-90 (Tex. Civ. App. 1937). Cf. Thomas

v. Washington Gas Light Co., 448 U.S. 261, 281-83 (1980)

6. See footnote 9 infra.

A17

(plurality opinion) ( “ [Tjhe critical differences between

a court of general jurisdiction and an administrative agency

with limited statutory authority forecloses the conclusion

that constitutional rules applicable to court judgments

are necessarily applicable to workmen’s compensation

awards.” ) 7

The conclusion that section 1738 does not require that

we give preclusive effect to the findings of a state adminis

trative agency does not end the inquiry. Common law

principles may require that we apply rules of preclusion.

See McDonald v. City of West Branch, ..... . U.S. .....

....... , 104 S. Ct. 1799, 1802 (1984). In determining whether

to create or apply a judge-made rule of preclusion in

the circumstances presented by this case, it is appropriate

to consider the question in light of the legislative history

and purpose of section 1983.

7. The Court in Thomas v. Washington Gas Light Co., 448

U.S. 261 (1980) (plurality opinion), ultimately held that “Full

faith and credit must be given [by the District of Columbia] to

the determination that the Virginia [Workers’ Compensation] Com

mission had the authority to make . . . .” Id. at 282-83. It is

unclear whether the Court believed this result was required by

the full faith and credit clause of the Constitution, Art. IV, § 1,

or the full faith and credit statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1738. The full faith

and credit clause requires each state to give full faith and credit

to the “judicial Proceedings” of another state. The full faith and

credit statute requires every court within the United States to

give full faith and credit to the judicial proceedings of any

court of another state. Although the Thomas Court cited section

1738, the Court’s substantive discussion focused on the full faith

and credit clause, Id. at 279, and on the applicable “constitutional

rules,” id. at 282. The Court therefore must have: (1) re

garded the District of Columbia as a “state” subject to both the

full faith and credit clause and the full faith and credit statute;

or (2) not considered or ruled on the difference in language in

the clause and the statute. If the former, the Thomas case is in

applicable here because a federal court is bound only by the stat

ute, which requires that we give full faith and credit only to the

judicial proceedings of state courts. If the latter, we are unaware

of any dispositive Supreme Court decision. We therefore adopt

the rule clearly articulated by the Fourth Circuit.

A18

In Allen and Migra, the Court stated in dictum that

the legislative history and purpose of section 1983 could

not override “ traditional rules of preclusion.” See Allen,

449 U.S. at 99; Migra, 104 S. Ct. at 897. We do not

believe that the Court’s language may be read to prevent

consideration of the history and purpose of section 1983

when a court is considering not whether to override a

common law rule of preclusion but whether to develop

such a rule in the first instance. See McDonald v. City

of West Branch, ....... U.S.......... , ..... 104 S. Ct. 1799,

1803,1804 (1984).

As noted previously, the Supreme Court has stated

that common law principles of res judicata may be appli

cable when an administrative agency “ is acting in a judi

cial capacity.” See United States v. Utah Construction

& Mining Co., 384 U.S. 394, 422 (1966). The rule in

Utah Construction has been applied primarily to the ad

ministrative decisions of federal agencies when principles

of res judicata are asserted in a subsequent federal court

proceeding. Rarely have courts considered whether

a state administrative decision is entitled to preclusive

effect when a claimant asserts a federal right in a subse

quent federal action other than one based upon section

1983. Consequently, the question is not whether section

1983 can override an existing common law rule of preclu

sion, but whether we ought now to develop and apply

such a rule in a section 1983 action.

The legislative history and purpose of section 1983

has been summarized by the Supreme Court:

The legislative history [of section 1983] makes evident

that Congress clearly conceived that it was altering

the relationship between the States and the Nation

with respect to the protection of federally created

A19

rights; it was concerned that state instrumentalities

could not protect those rights; it realized that state offi

cers might, in fact, be antipathetic to the vindication

of those rights; and it believed that these failings

extended to the state courts.

. . . The very purpose of § 1983 was to interpose

the federal courts between the States and the people,

as guardians of the people’s federal rights—to protect

the people from unconstitutional action under color

of state law, “whether that action be executive, legis

lative, or judicial.” Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. [339,

346 (1879)].

Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225, 242 (1972). This view

of the legislative purpose of section 1983 echoed the

view expressed in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961):

It was not the unavailability of state remedies but

the failure of certain states to enforce the laws with

an equal hand that furnished the powerful momentum

behind [section 1983].

. . . It is abundantly clear that one reason the legis

lation was passed was to afford a federal right in

federal courts because, by reason of prejudice, passion,

neglect, intolerance or otherwise, state laws might not

be enforced and the claims of citizens to the enjoy

ment of rights, privileges, and immunities guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment might be denied by

the state agencies.

Id. at 174-75, 180 (emphasis added). The legislative his

tory and purpose of section 1983, as explicated by the

Supreme Court, is incompatible with application of a ju

dicially fashioned rule of preclusion that would bind a

A20

court considering a section 1983 claim to the unreviewed

findings of a state administrative agency. Congress pro

vided a civil rights claimant with a federal remedy in

a federal court, with federal process, federal factfinding,

and a life-tenured judge. The Court in Allen and Migra

did not disagree with the reading of the legislative history

and purpose of section 1983 as explained in Mitchum v.

Foster and Monroe v. Pape. See Allen, 449 U.S. at 98-

99; Migra, 104 S. Ct. at 897. The conflict that animated

the decisions in Allen and Migra—the conflict between

section 1983 and section 1738 and common law rules of

preclusion—is not present when the prior adjudication was

conducted in a state administrative agency rather than

a state court. In the absence of such a conflict, we

decline to undermine the purpose of section 1983 by cre

ating a rule that would give preclusive effect to the prior,

unreviewed decision of a state administrative agency.

At least implicit in the legislative history of section

1983 is the recognition that state determination of issues

relevant to constitutional adjudication is not an adequate

substitute for full access to federal court. State adminis

trative decisionmakers, unlike federal judges, generally

do not enjoy life tenure. Because they are subject to

immediate political pressures from which federal judges

are immune, state administrative decisionmakers encounter

more difficulty in achieving the broad perspective neces

sary to approach sensitively the issues raised by those

whose claims often are dramatically anti-majoritarian. The

importance of access to a decisionmaker who is insulated

from majoritarian pressure is particularly important in

those fact-intensive cases, such as race discrimination cases,

in which factual findings of motive and intent play major

roles in the litigation.

A21

Of course, this argument has been rehearsed before

in the context of the debate over the forum allocation

decision as between federal and state courts. See Neu-

borne, The Myth of Parity, Harv. L. Rev. 1105 (1977).

The argument is no less valid for being repeated here.

Although similar arguments for denying res judicata effect

to state court judgments were rejected in Allen and Migra,

that rejection, as we have noted, was based upon the

congressional directive embodied in section 1738. That

directive is not applicable here, and the very real differ

ences between a state and federal forum legitimately play

a role in the decision whether to create a rule that would

give preclusive effect to the unreviewed findings of a

state administrative agency.

Moreover, there are significant differences between

the state judicial and administrative forums that counsel

against federal court deference to the decisions of the

latter even though Congress has required deference to

the decisions of the former. Primary among these differ

ences is the process for selecting the decisionmaker. State

court judges, like federal judges, have been selected

through a political process that places a premium on the

candidate’s ability to make difficult choices in the face

of competing, often irreconcilable, highly desirable goals.

In antiquarian terms, the political selection process places

a premium on the candidate’s practical judgment. By

contrast, the process for selecting administrative decision

makers is bureaucratic rather than political. As a result,

the selection process places a premium on technical com

petence, narrowly conceived, rather than practical judg

ment. The candidate generally is expected to apply one

regulatory scheme to a narrow range of possible factual

situations. Consequently, the administrative decision

maker, unlike the state or federal judge, is not selected

A22

on the basis of his or her ability to apply a broad, range

of principles to an ever-broadening range of social conflicts

and to exercise the practical judgment necessary to reach

a just result in a particular constitutional case. Although

an agency decision generally is subject to review in the

state’s courts, the deferential standard of review employed

is not adequate fully to protect federal rights in light

of the often fact-intensive nature of the constitutional in

quiry.

The differences between the nature of the state ad

ministrative and federal judicial forums compel us to con

clude that, regardless of the similarities in the formal

procedures used in those forums, according preclusive ef

fect to unreviewed state administrative determinations is

incompatible with the full protection of federal rights en

visioned by the authors of section 1983.

Our discussion of the differences between administra

tive and judicial forums should not be read as doubting

the worth of state administrative determination of civil

rights issues. Our rule ultimately is one that encourages

resort to speedy, efficient state administrative remedies

and thus maximizes the choices of forum available to the

litigants. If the claimant prevails before the administra

tive agency, the defendant may appeal to the state courts

and thus, pursuant to the rule in Allen, Migra, and Kremer,

preclude federal court intervention. If the claimant loses

before the agency, the claimant may either pursue an

appeal in the state courts or bring an action in federal

court. The rule of non-preclusion maximizes the forum

choices by encouraging the claimant to pursue administra

tive remedies when, if rules of preclusion were applicable,

the claimant would forego the administrative adjudication

and proceed immediately to federal court. See McDonald

v, City of West Branch, .... . U.S.......... , ....... , 104 S. Ct.

A23

1799, 1804 n .ll (1984); Gargiul v. Tompkins, 704 F.2d 661,

667 (2d Cir. 1983), vacated on other grounds, ....... U.S.

....... , 104 S. Ct. 1263, on remand, 739 F.2d 34 (1984) ;8

Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799, 802 (4th Cir, 1982). Of

course, it is the province of Congress, not the courts, to

make forum allocation decisions. When the issue comes

to us in the form of the question whether to create a

common law rule of preclusion, we have no choice but to

make the decision that best comports with reason and the

relevant statutory scheme. As we have shown, the legis

lative history of section 1983 supports, if it does not com

pel, the result we reach.

A rule denying preclusive effect to an unreviewed

state administrative determination in a subsequent section

1983 action also has the salutary effect of preserving

congruence between the rules of preclusion in Title VII

and section 1981 (or 1983) actions. Claims under these

statutes often are asserted in the same lawsuit. The Su

preme Court has made clear that an unreviewed state

administrative determination will not preclude later resort

to Title VII, and we can find no reason why a different

rule should apply to claims under section 1981 or 1983.

One commentator has observed:

Application of preclusion as to part of the case saves

no effort, does not prevent the risk of inconsistent

findings, and may distort the process of finding the

issues. The opportunity for repose is substantially

weakened by the remaining exposure to liability. In

sistence on preclusion in these circumstances has little

value, and more risk than it may be worth.

18 C. Wright, A. Miller & E. Cooper, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 4471 at 169 (Supp. 1985). Although

8. See footnote 9 infra.

A24

this rationale for a rule of non-preclusion applies only

when a section 1981 or 1983 claim is asserted together

with a Title VII claim, the joining of those claims occurs

in a non-trivial number of cases.

The decision we reach today is at odds with the result

reached in other circuits; the existing plethora of views

on the issue makes conflict inevitable. See, e.g., Zanghi

v. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, 752 F.2d 42,

46 (2d Cir. 1985) (giving preclusive effect to a state ad

ministrative determination on authority of Utah Construc

tion); Gargiul v. Tompkins, 704 F.2d 661, 667 (2d Cir.

1983) (not giving preclusive effect to a state administra

tive determination because the claimant had not

“ cross [ed] the line between state agency and state judicial

proceedings” ; citing Keyse v. California Texas Oil Corp.,

590 F.2d 45, 47 n.l (2d Cir. 1978)), vacated on other

grounds, ...... . U.S. ....... , 104 S. Ct. 1263, on remand, 739

F.2d 34 (1984) ;9 Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799, 801-02

(4th Cir. 1982) (not giving preclusive effect to state ad

ministrative determination because contrary rule would

encourage claimants to bypass agency remedies); Steffen

v. Housewright, 665 F.2d 245, 247 (8th Cir. 1981) (per

curiam) (purporting to give preclusive effect to state ad

ministrative determination, but holding that agency’s find

9. The Supreme Court vacated Gargiul and remanded the

case in light of Migra. On remand, the Second Circuit panel held,

without analysis, that Migra barred all the claims asserted by

the plaintiff. We believe that the principle for which we cite

the original panel opinion in Gargiul is still good law. The orig

inal panel had held, in addition to the principle for which we cite

the case, that a prior state court proceeding does not bar federal

court consideration of constitutional claims not actually litigated

and determined in the state court proceeding. It is the latter

principle that was rejected by the Court in Migra and for which

the original Gargiul opinion was most likely vacated. There is

nothing in Migra to cause the panel on remand to have ques

tioned its holding with respect to an unreviewed state adminis

trative decision.

A25

ings may be disregarded if they are “ clearly erroneous” );

Patsy v. Florida International University, 634 F.2d 900,

910 (5th Cir. 1981) (en banc) (stating that state adminis

trative determinations “carry no res judicata or collateral

estoppel baggage into federal court” ), rev’d on other

grounds sub nom. Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S.

496 (1982); Anderson v. Babb, 632 F.2d 300, 306 n.3 (4th.

Cir. 1980) (per curiam) (not giving preclusive effect to

a state administrative determination because of the “deli

berately intended political composition of the tribunal” );

Taylor v. New York City Transit Authority, 433 F.2d 665,

670-71 (2d Cir. 1970) (giving preclusive effect to state

administrative determination on authority of workers’ com

pensation cases decided on the basis of full faith and cred

it clause). The analysis used and result reached in this

opinion attempt to make sense of a complex area of the

law and to remain faithful to both the teachings of the

Supreme Court and the intent of Congress as manifested

in section 1983 and its history.

The judgment of the district court is reversed.

In light of this disposition, the appellees’ requests for

attorneys’ fees and costs for defense of a frivolous appeal

are denied. Elliott shall recover the costs of this appeal.

A26

(Filed May 12, 1984)

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE W ESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

EASTERN DIVISION

No. 82-1014

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT,

Plaintiff,

vs.

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, ET AL„

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM DECISION ON DEFENDANTS’

AM ENDED MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

This is an action for preliminary and permanent in

junctive relief and $1,000,000.00 in damages pursuant to

42 U.S.C. §1983, and Title VI and Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§2000(e),

et seq., brought by Robert B. Elliott, a nontenured faculty

member with the rank of Associate Agricultural Extension

Agent of The University of Tennessee’s Agricultural Ex

tension Service (AES), now assigned to its Shelby County

office.

Plaintiff alleges that defendants have violated his civil

rights on the basis of race, 42 U.S.C. §1981, and have

conspired to deprive him of civil rights under 42 U.S.C.

§§1985 and 1986. In addition to his individual action,

plaintiff seeks to have this action certified and maintained

as a class action for which he seeks injunctive and declara

tory relief from discrimination on the basis of race.

A27

When the plaintiff filed this action in December of

1981, the dean of the AES had written to plaintiff stating

that a due process hearing would be conducted under

the Contested Case Provisions of the Tennessee Uniform

Administrative Procedures Act (UAPA), T.C.A. §4-5-301,

et seq., to determine whether or not plaintiff’s employment

should be terminated on the basis of gross misconduct,

inadequate work performance, and improper job behavior.

Because this action was filed prior to any due process

hearing in this employment disciplinary matter, the Uni

versity defendants moved the Court to dismiss on the

basis, inter alia, that this civil rights action was premature

and was not ripe for judicial review.

Initially, this Court entered a temporary restraining

order which was lifted later by Judge Wellford on March

29, 1982, when he ruled that the defendants would not

be restrained from taking job action against plaintiff, in

cluding termination, after a full and adequate hearing.

After dissolution of the temporary restraining order,

a UAPA hearing was convened in Jackson, Tennessee,

on April 26, 1982. It continued with various recesses until

its conclusion five months later on September 29, 1982.

The administrative record consists of 55 volumes of tran

script containing over 5,000 pages of the testimony of over

100 witnesses and 153 exhibits. Plaintiffs employment

has never been interrupted and the final UAPA order

requires that plaintiff’s employment continue.

The initial order of the Administrative Law Judge

(ALJ), a ninety-six-page document containing extensive

findings of fact and conclusions of law, was entered on

April 4, 1983, in accordance with T.C.A. §4-5-314 (b). It

ruled that the agency proved four of the eight charges

filed against plaintiff, but failed to prove four of the

A28

charges. The ALJ also ruled that the plaintiff failed to

prove, as a defense, that the defendants’ motive in seeking

plaintiffs discharge was racial.

Instead of ordering that plaintiff be terminated, the

ALJ ordered that the employee be reassigned to a dif

ferent work station for a one-year period and that plain

tiff be given new supervisors. Previously, plaintiff was

assigned in the Madison County Office of the AES under

the supervision of the Extension Leader, Curtis Shearon.

Both plaintiff and the agency filed petitions for re

consideration of the initial order, which were overruled.

Thereafter, plaintiff appealed the initial order, pursuant

to T.C.A. §4-5-315, to Dr. W. W. Armistead, University

of Tennessee Vice President for Agriculture, who, on Au

gust 1, 1983, filed the final order in the UAPA case. Dr.

Armistead affirmed and incorporated the initial order by

reference and held, in part:

My review of the record [the ALJ ruling] in this

case convinces me that it is supported by the evi

dence, and that no error was committed by the Ad

ministrative Judge in reaching such decision. I am

also convinced from my review of the record that

the action of the Extension Service in proposing the

termination of employee’s services was not motivated

by employee’s race but by a desire to terminate

employee for what the Extension Service sincerely

believed to be inadequate job performance and inade

quate job behaviour. The lengthy due process hear

ing afforded employee and the lengthy hearing record,

which has been filed with me, are ample evidence

of such fact. [Attachment C, Plaintiff’s Motions].

In accordance with such final order, plaintiff, on

August 31, 1983, was transferred for one year to Shelby

A29

County. Plaintiff was not reclassified but remains in his

same status as a nontenured faculty member, with the

same rank, same salary, and same benefits as before.

The only change ordered by the final order was a change

of work station for one year and a change of supervisors,

approximately 80 miles distance from his former station.

Plaintiff did not seek a stay of the final order from

Vice President Armistead, even though such stay is pro

vided for in the UAPA, T.C.A. §4-5-316. More signif

icantly, plaintiff did not seek judicial review of the UAPA

final order under T.C.A. §4-5-322, which requires that

a petition for judicial review must be filed in chancery

court within 60 days after the entry of the final order.

Instead, plaintiff delayed eighty-four days after entry

of the final order and filed the pending action in this

Court, a petition for a TRO and preliminary injunction

or, alternatively, a stay of the final agency order almost

two months after plaintiffs transfer to Shelby County

was complete and effective, in an attempt to restrain

what had already occurred.

Plaintiff attacks the merits of the August 1, 1983 final

UAPA agency order, claiming that the final administra

tive order is arbitrary, retaliatory, wrongful, illegal, har

assing, unnecessary and damaging to his reputation. How

ever, since plaintiff did not appeal timely to the proper

court, the merits of the August 1, 1983 final order are

not reviewable here in this Court and that proceeding is

res judicata to any attack on the merits of that order in

this, or any other, court.

It is defendants’ position that summary judgment is

proper in favor of the University of Tennessee defendants

for the following reasons.

A30

1. In so far as the plaintiff seeks to have this Court

serve as an appellate tribunal over the IJAPA hearing,

this Court lacks appellate jurisdiction to review the merits

of the final order of the UAPA hearing which ruled upon

the same issues present in this case. Jurisdiction for

judicial review of a final UAPA order is vested in the

Tennessee chancery courts under T.C.A. §4-5-322.

2. The final order of August 1, 1983 is res judicata,

which bars any attempt to attack the merits of that order.

Exclusive jurisdiction to judicially review the merits

of a final order entered in a UAPA contested case is in

the Tennessee chancery courts. United Inter-Mountain

Telephone Company v. Public Service Commission, 555

S.W.2d 389 (Tenn. 1977): T.C.A. 4-5-322(a).

It is a hornbook principle that judicial review of

the merits of a final administrative decision is proper only

in accordance with the statute which provides for judicial

review. Plaintiff’s post administrative hearing motions

for a TRO, a stay of the UAPA final order, and prelim

inary injunction are obvious efforts to attack the merits

of this UAPA contested case decision and should have

been filed, if at all, in chancery court within the pre

scribed 60-day period. The final agency order so stated:

A petition for reconsideration of this order may be

filed within ten (10) days after entry, as set forth

in T.C.A. §4-5-317. Judicial review of such order

may be had by filing a petition for review in a Chan

cery Court having jurisdiction within sixty (60) days

from the entry of this order, as provided by T.C.A.

§4-5-322.

Plaintiff deliberately chose to contest the disciplinary

charges against him by means of a UAPA contested case

A31

in accord with T.C.A. §4-5-301, et seq. Having invoked

the due process provisions of the UAPA through a final

agency order, plaintiff was required to follow the require

ments of the Tennessee law to review the administrative

final order.

Moreover, even in a proper case where federal courts

have jurisdiction, the federal courts are not the proper

forum to review the merits of an administrative disciplin

ary proceeding against a government employee. Gross v.

University of Tennessee, 448 F.Supp. 245 (W.D. Tenn.

1978), affd, 620 F.2d 109 (6th Cir. 1980).

Plaintiff makes no claim of denial of procedural due

process. Nor can he in light of the long exhaustive evi

dentiary hearing in which plaintiff presented more than

ninety witnesses, and cross-examined some of the agency’s

witnesses for more than thirty hours each. Plaintiff clearly

has received full protection in this due process hearing,

as required in Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564

(1972), and Perry v. Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593 (1972).

That this court simply is the wrong place to attack

such a transfer of job location or change of supervisors

was made clear by the United States Supreme Court in

Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S. 349 (1976). In Ramsey v. TV A,

502 F.Supp. 230, 232 (E.D. Tenn. 1980), the court said:

This Court is not designed to sit in judgment of per

sonnel decisions best left to those with expertise in

personnel matters and familiarity with the workings

and problems of the agency concerned.

Having demonstrated that this Court is not the forum

in which the plaintiff may seek appellate review of the

administrative ruling, the Court now wishes to treat the

question pertaining to res judicata.

A3 2

When plaintiff first filed this case, the personnel dis

ciplinary hearing by the administrative agency had not

been conducted. Plaintiff, therefore, sought to forestall

the administrative hearing upon his alleged misconduct

and he sought class relief whereby the Court would in

vestigate and supervise all phases of employment relations

in the AES, similar to the school desegregation cases. When

injunctive relief against the disciplinary proceedings was

denied in this court, plaintiff litigated in the UAPA pro

ceeding all of the issues about which he now complains,

including allegedly racially discriminatory conduct by his

employers. As heretofore noted, the final disciplinary or

der was appealable to courts of record in the court system

of Tennessee.

This Court is convinced that the civil rights statutes

set forth in Title 42 of the United States Code, and upon

which plaintiff relies for this Court’s jurisdiction, were

not intended to afford the plaintiff a means of relitigating

what plaintiff has heretofore litigated over a five-month

period. Therefore, this Court should dismiss the case upon

the doctrine of res judicata.

For the above reasons, this Court concludes that a

summary judgment should be granted in favor of all de

fendants and the Clerk is directed to enter a judgment of

dismissal with prejudice in favor of all defendants.

ENTER: This 2nd day of May, 1984.

/ s / Robert M. McRae, Jr.

Robert M. McRae, Jr.

United States District Judge

A33

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

O ffice of the V ice

P resident for

A griculture

P. O. Box 1071

Institute of A griculture

Instruction, research, exten

sion in agriculture and

veterinary medicineKnoxville, Tennessee

37901-1071

(615) 974-7342

Research, extension in home

economics

August 1, 1983

Messrs. Williams and Dinkins

Attorneys at Law

203 Second Avenue, North

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Mr. Alan M. Parker

Associate General Counsel

The University of Tennessee

810 Andy Holt Tower

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-0184

Re: The University of Tennessee Agricultural

Extension Service v. Robert B. Elliott

Dear Sirs:

This decision constitutes the final order in this matter

and is entered pursuant to T.C.A. § 4-5-315.

The initial order, entered on April 4, 1983 by the Ad

ministrative Judge, concluded that although Mr. Elliott

was guilty of four of the eight charges placed against him,

he should not be terminated as proposed by the Extension

Service. Instead, the employee was ordered reassigned

for a twelve month period under the direct supervision

of the District and Associate District Supervisors of Dis

A34

trict One. Placing employee under District One super

vision precludes transfer to “virtually any county in the

State,” as employee contends. To the extent such order

can be otherwise construed, it is modified accordingly.

Such action will insure that employee remain in District

One. In ordering such a transfer, the Administrative Judge

recognized the fact that it would be difficult, if not im

possible, for Mr. Elliott and his present supervisor, Mr.

Curtis Shearon, to work together in a harmonious rela

tionship in the Madison County Agricultural Extension

Office.

My review of the record in this case convinces me

that such conclusion is undoubtedly true, is supported by

the evidence, and that no error was committed by the Ad

ministrative Judge in reaching such decision. I am also

convinced from my review of the record that the action

of the Extension Service in proposing the termination of

employee’s services was not motivated by employee’s race

but by a desire to terminate employee for what the Ex

tension Service sincerely believed to be inadequate job

performance and inadequate job behaviour. The lengthy

due process hearing afforded employee and the lengthy

hearing record, which has been filed with me, are ample

evidence of such fact. It seems to me that the very es

sence of a due process hearing is to give an employee

charged with an offense an opportunity to defend himself

of the charges against him. Here, the employee was af

forded ample opportunity under the law to defend him

self before he was terminated and was found not guilty

of four of the eight charges. The Administrative Judge

found that conviction of the remaining charges was not

sufficient under the circumstances to warrant dismissal.

The Extension Service did not appeal such finding and

conclusion.

A3 5

I have considered carefully the issues raised by em

ployee in this appeal and find them to be without merit

for the reasons set out in the well-i’easoned and detailed

initial order of the Administrative Judge, which I adopt

as my own and as a part of the final order in this matter.

Accordingly, it is my decision to sustain the findings and

conclusions of the Administrative Judge as they relate to

this appeal and deny employee’s appeal.

A petition for reconsideration of this order may be filed

within ten (10) days after entry, as set forth in T.C.A.

§ 4-5-317. Judicial review of such order may be had by

filing a petition for review in a Chancery Court having

jurisdiction within sixty (60) days from the entry of this

order, as provided by T.C.A, § 4-5-322.

Entering this 1st day of August, 1983.

/ s / W. W. Armistead

W. W. Armistead

Vice President

A3 6

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE

ADMINISTRATIVE APPEAL

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE AGRICULTURAL

EXTENSION SERVICE,

Employer,

v.

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT,

Employee.

INITIAL ORDER

INTRODUCTION

Pursuant to the contested case provisions of the Ten

nessee Administrative Procedures Act (U APA), T.C.A. Sec.

4-5-301 et seq., this administrative law judge and hearing

examiner (hearing examiner hereafter), an agency staff

member having been assigned this role by W. W. Armi-

stead, Vice President for Agriculture The University of

Tennessee Institute of Agriculture, conducted a hearing

in the above styled case. The hearing was convened on

April 26, 1982, in the auditorium of the Madison County

Agricultural Complex in Jackson, Tennessee. Employee’s

motion to continue was denied and testimony was heard

on April 26-29, 1982. The hearing recessed and thereafter

reconvened on July 13-16, 1982; July 26-28, 1982; August

9-13; 1982; August 16-August 18, 1982 and August 23, 1982

during which day the hearing recessed at the request of

employee upon receiving news of the death of his wife’s

uncle in Chicago, Illinois. The hearing was reconvened

September 27-29, 1982 and then recessed until October

25, 1982 at which time employee moved for a continuance

A3 7

of sixty days based on recommendation of his physician,

Dr. Robert Winston, who testified in support of the motion

that in his opinion Robert Elliott could carry on a normal

work schedule but to continue the stress and strain of

the hearing could lead to a stroke and possible paralysis.

Dr. Winston, an internist and general practitioner, had ear

lier testified as a witness for employee. While awaiting

a second opinion from neurologist, Dr. James Spruill whom

Dr. Winston had called in during the week of October

11, 1982 while employee was hospitalized and under Dr.

Winston’s care, to evaluate certain tests, the University

offered to waive further cross examination of employee

and conclude the hearing. Upon agreement of the parties,

the motion to recess for 60 days became moot and after

twenty-eight days of testimony and argument, the hearing

was concluded. Employee’s motion for a directed verdict

at the conclusion was denied.

After reviewing all the testimony some 104 witnesses

all evidence of record which included 159 exhibits, argu

ments of counsel, and the parties proposed findings of

fact and conclusions of law, the following findings of fact

and conclusions of law are rendered and an initial order

entered accordingly.

The purpose of this hearing was to determine whether

or not the employment of Madison County Associate Agri

cultural Extension Agent, Robert B. Elliott (hereafter

Elliott, or employee) should be terminated for alleged

inadequate work performance and inadequate and/or im

proper job behavior.

By letter dated December 18, 1981, Dr. M. Lloyd Dow-

nen, (hereafter Downen, employer or Dean) of The Uni

versity of Tennessee Agricultural Extension Service (here

after University, employer, UTAES or AES) informed

A3 8

Elliott that “due to the serious allegations and incidents

of inadequate job behavior which have continued this year,

I have decided to propose that your employment with

The University of Tennessee Agricultural Extension Ser

vice be terminated for inadequate job performance and

inadequate job behavior” . (Exhibit #115). Elliott was

notified of his right to a hearing to contest the charges

against him either under Section 500 of The University

of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture’s (UTIA) Personnel

Procedures or the contested case provisions of the Ten

nessee Uniform Administrative Procedures Act (UAPA).

On December 22, 1981, the employee informed Downen

by letter that he was electing to contest the charges against

him in a hearing under the UAPA. Subsequently, Elliott

filed a civil rights action in the United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee seeking dam

ages and both temporary and permanent injunctive relief

against the University and its officials from taking any

action which would affect his employment status. The

court entered a temporary restraining order which enjoined

the University from taking any further action towards

the commencement of this hearing. Upon dissolution of

the temporary restraining order Federal District Judge

Harry Wellford specifically allowed this hearing to proceed

as long as it was held prior to any determination to termi

nate Elliott’s employment. On March 1, 1982, Downen

wrote to employee Elliott (Exhibit #118) specifically

charging him as follows:

You are charged with inadequate work performance

in that you have failed in a timely and proper manner

to complete assignments given to you pursuant to your

job description by the Madison County extension

leader and failed to properly carry out instructions

given to you by your supervisors. You are charged

A39

with inadequate job behavior in that you have played

golf during working hours without permission and

without taking leave. You are also charged with con

ducting your personal cabinet business during working

hours. You are charged with making, or allowing,

harassing phone calls to be made from your home

telephone to Mr. Jack Barnett, a resident of Gibson

County. You are charged with improper job behavior

during the incident at Murray Truck Lines on June

18, 1981 and at the Madison County livestock field

day on July 24, 1981. You are charged with violating

The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture

work rule #4 , leaving work prior to the end of the

work period, and repeated failure to inform the super

visor when leaving a work station or work area. You

are charged with violating work rule #13, the use

of abusive language. You are charged with violating

work rule #24, behavior unacceptable to the Uni

versity or to the community at large. You are charged

with violating work rule #25, insubordination or re

fusal of an employee to follow instructions or to per

form designated work where such regulations or work

normally or properly may be required of an employee.

Thereafter, pursuant to the UAPA, T.C.A. Sec. 4-5-

101 et seq. employee moved for a more definite statement.

Employee responded as follows:

1. The employee is charged with playing golf during

working hours in that during the spring of 1976

he was caught on the golf course at Woodland

Hills Country Club in South Madison County dur

ing working hours and without permission by the

Madison County extension leader and district su

pervisor. The employee gave assurance that he

would not play golf again during working hours.

A40

Thereafter, on July 31, 1981 the employee, without

permission, played golf during working hours at

the Jackson Golf and Country Club. Employee

is also charged with recently playing golf without

receiving prior permission to leave the work sta

tion and without making previous arrangements

to take annual leave.

2. The employee is charged with engaging in the

commercial business of making and installing cab

inets during working hours in that the employee

in 1980 on numerous occasions visited a residen

tial dwelling in Jackson, Tennessee which was

under construction and which the employee had

been low bidder on the construction and installa

tion of kitchen cabinets. Such visits to said

dwelling were during working hours. The date

of the last visit was June 9, 1980. The employee

is also charged with other acts of engaging in

personal business during working hours, proof of

which will be adduced at the hearing of this mat

ter.

3. The employee is charged with making, or allowing

to be made, harassing telephone calls to Mr. Jack

Barnett, a resident of Gibson County, in that anon

ymous telephone calls were made at all hours

of the day and night to Mr. Barnett’s residence,

and upon making a complaint to South Central

Bell Company, such anonymous calls were traced

to the employee’s residence telephone in Gibson

County. Such charge, if sustained, is alleged

to violate work rule #24 of the UTIA in that

such activity represents behavior unacceptable

to the University or the community at large.

A41

Such anonymous telephone calls were harassing

in that such calls were also made in the late-night