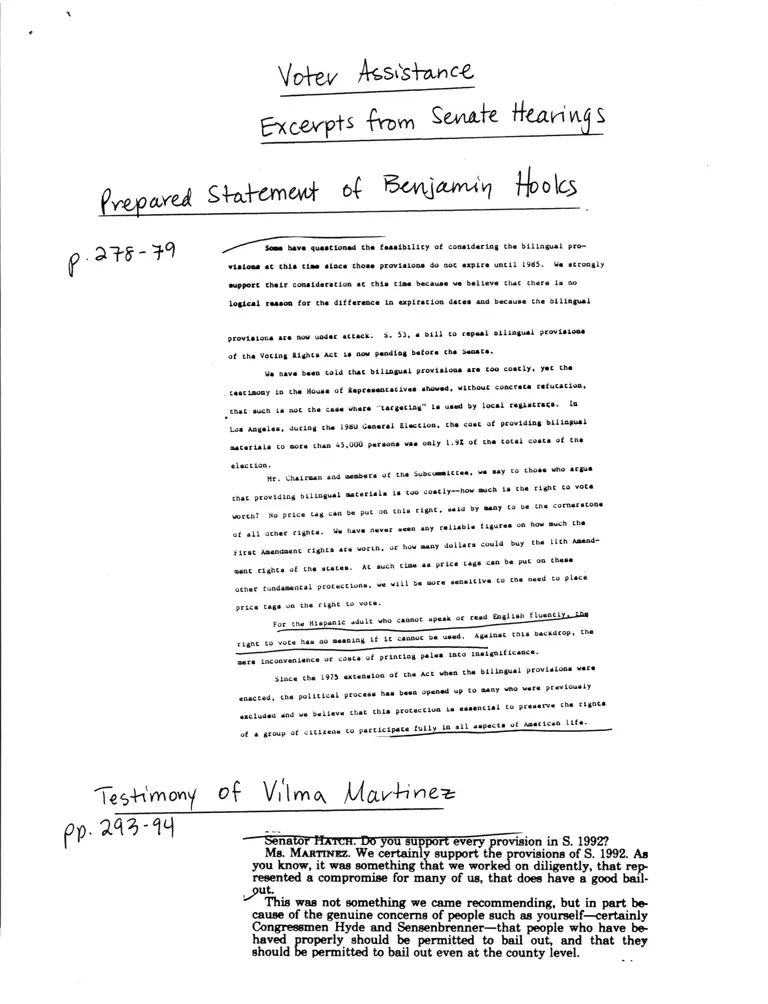

Excerpts from Senate Hearings: Voter Assistance (Prepared Statements and Testimony)

Unannotated Secondary Research

April 28, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Excerpts from Senate Hearings: Voter Assistance (Prepared Statements and Testimony), 1982. 41671141-dc92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b0ee57ce-9d23-45f9-8364-e83fca5227ad/excerpts-from-senate-hearings-voter-assistance-prepared-statements-and-testimony. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

VO‘H’A/ A‘zSQSJr'ance

Excevpn From Smoke. ”Caring:

Wwaxdz Slocl'cmowl 0% MW»; Hook;

f . 2?,8 _ 3.9 / 3. have quoutonod tho fusibxucy of considering the bilingual pIO‘

‘1OIOII a: this zin- alone tho-o provts1on- do no: oxplrn unttl 1985. Ho strongly

support that! consideration a: this zino because on believe that there Is no

loglcol reason for the d1fforonco 1n expiration datcs and bee-use the bilingual

provlstono or. now undo: attack. 5. 53. a blll to repeal ollxnaunl provtsxono

at tho Vottnl lights ALI to non pending befor- (ha Sonata.

Ha have bun told that bilmgual proviuon- on too costly. yo: tho

.Lsstinnny 1n the House of llprascntstxvon should. without concrete roiuzation.

.thnt such Ls no: :ho can. whore ”targnztnu" to used by local roatstrazs. In

Lon Angolan. during tho lQHU General Electxon. thl cost of provtdtnl btltngunl

Iltnttlll to not. than “5.000 purlonl was only l.9l of tho total cost: of the

election.

Hr. Chalrlsn and mono-to of tho Subcu-ntzccc. no say (0 than. who argue

that provtdtng bllxngual unrest-ls to too coolly-—hou Inch 1- the rxgh: to votl

Horchl No price to; can be put on :hLu right, sold by Inny to on the cornerstone

of all other rights. He have never uenn any roll-bl. tlgur-n on hnu quh the

First Amendment rtlhts are north. or how many dollsrs could buy the llth Aland-

uon: rights of the states. A: such clnu as price tags can be put on than.

Other tundanantsl protections. we will be worn sensitive to tho need to place

print up on tho rtghc to vote.

For the Htipsnxc adult who cannot speak or read English fluunll

rxgh: to vote has no nannlng if x: cannot be used. Aguxnu: thxs backdrop. the

not. anonvonlonco or costs of ptxnttng pala- tnto luslgnlflconcn.

Since the [97} extension of the Act when tho biangunl provlslons were

enacted, the politlcnl procnss has boon opened up to many who unto pruvtously

ancludnd and us bolt-v. that chxs protection Ls ouncntlal to preserve tho rlxncs

of a group of citizen: to participate tully in All aspects oi Anortcon Life.

774._.__._.——~

Tee-Hmom/ 0? Vntlmm Mavfinea

F9201?“

W'

na - you an po every rowsnon in‘S. 1992?

Ms. MARTINEZ. We certain su ' '

. . pport t e rovxsxo f .

:2); 1511:!“ It was somethmg t at we work on diligglftlf, 31:92:25:

)u'lfh a compmmxse for many of us, that does have a‘good ball-

is was not something we came recommendin b t '

am of the genume concerns of people such as ygnrsglffcgmrtm'nbl:

h nedgressmen Hyde and Sensenbrenner—that people who have be-

:v ld geroperly. should be permitted to bail out, and that they

s on permltted to ball out even at the county level.

mp goo—Y- Pvepa.

L.

Voi'ey Assisi-am ca 9\

We heard them, we worked with them, and we have something

that we can live with, that we are proud of, that we would like to

see you support, that we would like to see the Senate support, and

that we would like to see the President sign.

Senator HATCH. The reason I ask that question is because I

wonder if you support section 208 which reads that “Nothing in

this act shall be construed in such a way as to permit voting assist-

ance to be given within the voting booth unless the voter is blind ~

or physically incapacitated.”

I ask this question that is because of your efforts in Garza v.

Smith, where MALDEF succeeded in having a Texas trial court de-

clare unconstitutional a State law denying assistance at the polls

to illiterates. So I wonder if you yourself believe that section 208 is

constitutional.

Ms. MARTINEZ. I believe that we need to look very carefully at

section 208. and I would like to submit something at a later time

for the record on what we think about section 208.

Senator HATCH. All right. /

In your statement you indicate that, “without action by Con-

gress, some of the major features of the Voting Rights Act are

scheduled to expire this year.” Can you tell me which, if any, provi-

sions of the act are scheduled to expire?

Ms. MARTINEZ. My understanding is that section 5 coverage

would end as of this year if no action is taken by the Congress.

Senator HATCH. Section 5 would not expire; some jurisdictions,

however, would be allowed finally to bail out after 17 years of good

conduct. You have been extremely critical of the legislation, S.

1995, introduced by our colleague, Senator Grassley, because you

say its provisions are vague. Perhaps this may be the case. I am

studying it and will have to study it further.

Ms. MARTINEZ. Good.

Senator HATCH. Can you tell me, however, what the House bill

means when it states that no jurisdiction shall be permitted to bail

out unless they have demonstrated that they have engaged in “con-

structive” efforts at expanded opportunity for minorities in the

election process? What does that all mean, in your view?

Ms. MARTINEZ. I would think there would be a variety of ways to?

do that. A jurisdiction could say. “Look, we took the bilingual elec-

tion provisions seriously," for example; “We have reduced how

much it costs us to insure that people have access to this;" “We

have targeted voters who need bilingual materials;” “We have

made them available." - ~

They could show, for example—they now are very aggressively,

in Spanish and other needed languages to reach citizens, talking to

them about how to register to vote and telling them what the v0

is in our society. It seems to me that there are a variety of things

that a jurisdiction wflWflofia—J”

' ‘ ' 1975 have brought the

’6 bilingual election requirements added to the VRA in . . f His-

‘ - hsh 3 US. citizens o

napamh't tomvota Eskimw uncgfitdigmlgfmnondEngwt who retainths nght to vet? as

$01:me right. Long held as “a fundamental right because it is preservative o

n denied these citizens until 1975,

rights."" the right to vote had effectively b3 courts had ordered bilingual 310°

vcd Si—aA-emw 6i: Vilma. Mal/Hue.»

\

except in a handful of instances where feds where the state's long tradition of bi-

/

Lions "_ and. the unique case of New Mexico,

WM‘M polling place.

6,). 309

(.310

Vol'a/ Assi‘s'ldm ca 5

Maximo ham hearings on

the VRA revealed that bilingual elections are cost-efficient, necessary and can be

implemented with ease by local election officials. Leonard Parrish. Registrar of

Voters in Los Angeles County, one of the largest election districts in the country, '

has developed a s stem for providing bilingual election materials that is one of the

most efficient we ve seen.

In the 1980 general election over 45,000 voters requested Spanish language mate-

rials in LA. County; the cost to the count was 1.9 percent of the total election cost.

Figures like these forced Rep. Paul M oskey, a long-time opponent of bilingual

”lections because they were too costly. to concede during his testimony at the House

hearings that “It seems to me that it can no longer be argued that the cost is exces-

sive for the bil' ballot. I do not make that argument. '

Nevertheleu. ilingual voting assistance was the subject of intense, extended

debate on the House floor during consideration of the Voting Rights Act. Yet two

amendments. one of which would have re ed all bilingual assistance—that is,

oral and written—and another, which wodl have repealed only the bilingual ballot

requirement, were defeated by margins greater than 2 to 1. Members of the House.

Republican and Democrat, were convinced overwhelmingly of the need for the bilin-

gual election requirements. The votes seemed to echo the words of House Majority

loader, Jim Wright, who said during the debate, “We have never made a mistake

when we broadened the franchise." /

’ When Congress enacted bilingual election requirementsin 1975. itdidsobsssdon

sserissofjudicial findingswhichcanbssummariudinthisdsciaioninTor-ruv.

“in order that the ghrase ‘the right to vote' be more than an empt platitude, a

voter must be able 0 ectively to register his or her political choice. ll'his' involves

more than hflcally being able to pull a lever or marking a ballot. it is simply

fundamen t voting instructions and ballots, in addition to any other material

which forms part of the official communication to registered voters prior to an else-

tion, must be in Spanish as well as English, ifths vote ofSpanisaleaking citizens

is not to be seriously in ' 3'“

Also significant was 0 Seventh Circuit affirmation of the lower court holding in

Puerto Rican Orgonizalion for Politic“ Action v. Kasper, which found that “if a

person who cannot read English is entitled to oral assistance, if a Negro is entitled

to correction of erroneous instructions, so a Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican is enti-

tled toauistance in the language hscan read or understand.“"Based on this deci-

sion and others bro ht on behalf of Puerto Ricans under Section 4(9). which was

£1." of the original oting Rights Act, bilingual elections have been conducted in

sw York, parts of New Jersey, Philadelphia and Chicago since the mid-1970's.

my add that when this Congress suspended the use of literacy tests in

1965, it did not send out a message advocating illiteracy. It was not suggested that

any person should be satisfied with not knowing how to read or write. Similarly,

bilingual election materials do not limit the primacy of the English language. To

the contrary, they stimulate interest and participation in a system in which voters

felt they have a voice. This feeling of belonging further stimulates and encourages

active citizens to improve their English language skills.