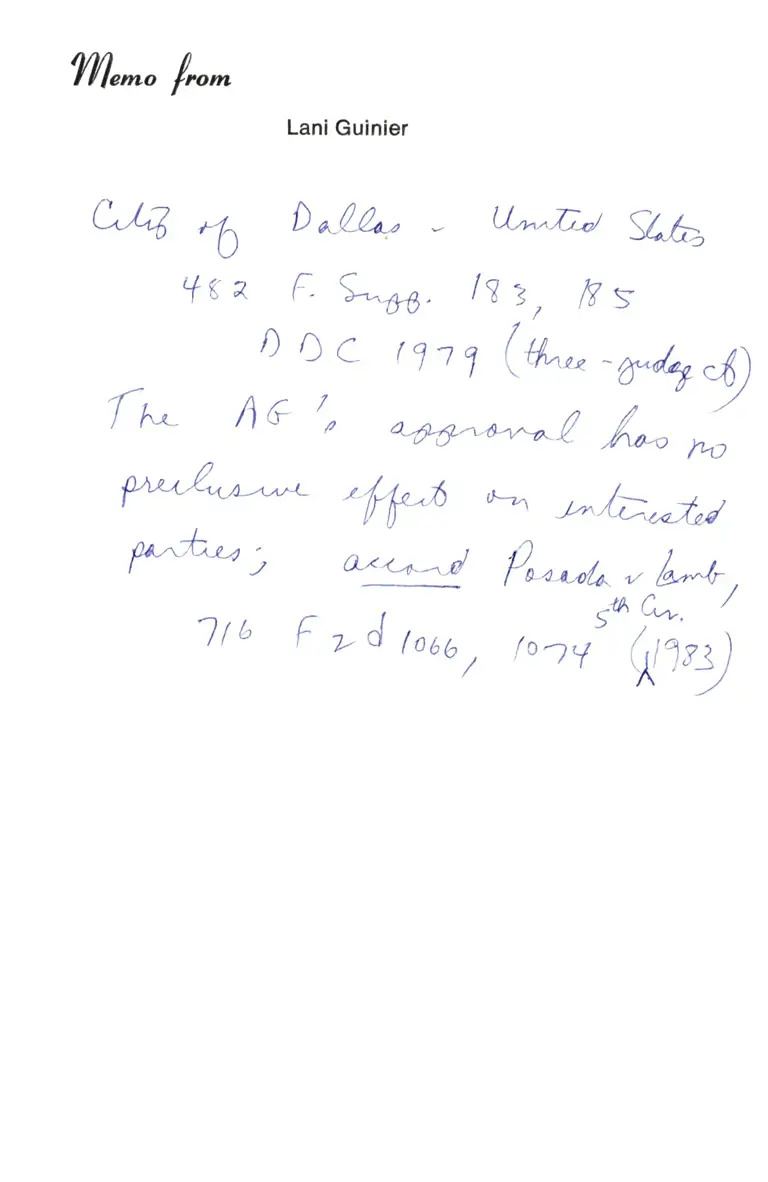

Attorney Notes from Guinier; Routing and Transmittal Slip from Jones to Smith

Working File

July 19, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Attorney Notes from Guinier; Routing and Transmittal Slip from Jones to Smith, 1982. 186a371c-dd92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1ccc1c7-fd7d-40a7-9aa9-676c0b54398c/attorney-notes-from-guinier-routing-and-transmittal-slip-from-jones-to-smith. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

//1"^o /*^

Lanl Guinler

C'LZ re D^Ur- v U^^D-/ SLb

tta €.;"o. lx3, fts

D D c (111 @"* -r4_4)

@ M o_1^ *^,(>,*,15

f^h* ; ^*.r^4 !r"r_a, A.,_lr,

'l/b F>d(on silu /

n r /o-t./ (ttr)

sl .

t

/11 FtJ 71

g?y . u

'w: L'ffihffi\.wffi

7e r FuJ t7/

(st" FuL frs

/1^^t v /1,*//^- G.

lu v ' Frd n of'r( 66 c* /tt)

l-4rb+,- 6 a/-^-V /-?\ Q-1r € gO€ 'o

/f*! @ ^d

.co ot/--n

ta(r^^rhr^ -1^ t',h,/6 A ' uh

&^n-.i cA r; Md^ { f-*^l /T /{/

h Dd /@*6

t lt

(,^1, 'aqb) 4.os vo i t s1'*J ''g vwv

YtWn n-*T l

wwy":42ffi'fr^

WVy--Affi rry V!

'@@ry

-?y [T-v n qZ-fu {h/ Oo37

("t tr

'aoA) st/ttTi tLh

-'"jq*_* TW,? ry

C79C,tr_2 r?_

-s2'72 p"! E ?s % y3 . yfn

W mW W Vry ry+*/rwWWb,.-??-lfW

'ry V -rV'u,/ d -v @e/ryw I --ry'ry

rt

"4*4 A C-;^A "U.^-8 t

br*U c-D .z<-a - /,ool f""?t I .r^/u U^

-AilG) c-1-- r'u,O *fu.U) I

:tafu;>, g ,\-f^--(^Lq U

Do-(&-e Pvr @6/7n_/S,A,/-rc 6{q €rJ'7Lt

(+a C,* tlr r )

b ouL*-l o/a*.uA,---l*-- 'o rulj

C-AtaY

z4a-- t

/+r^/i A,,hl^r; i'ln y K^A-"*^/ J^4r- 4_-.

L{ 3

H-.t"U*^ L t o

kr^L;,

t'1ulc fr*-"-

fu( rfz rvcrLf3

Ful ?19 / cra 7r,hf./

fu"ld^lov S(b nL(

S tg F, S-ffi I st7 -"^t4 r/-1 fuG<*. -,-JMMl#*ffi

l'.rr"J--^+ ,MA6 H-, d^- ,-*fA 4 p-o-*<-H-

.,1\,; "C.*q h u ."fi1 r.ate^ A p/,€--

-ft, , tu-lr-

t^- .,ud6 tv

*

v

6-,1,^ J (- -n--r-r,--<zto--'vt-s- ( a-lx-

1z Fe> 1 (Dc.

, p^^b4*^ G ,

{\^*4 f.1 s0)

e(rh

.t-"-^a-n/^^^r^^J-&

P-o/n;/4--,..) f-r.r-/o^,--4 .-.; L- e-q

{

,n--^-b., u C*-

C ,-r-b

?W v Cc . r l^-t 11. A^-Aj-- e G

31 'v (rJbs| (q4c^ tltt)

'(t'- '|

hvr-b /r--"r1 rf ,z-oLnn

/ ^, pi ' L/ - *7

,t--^-'<< <)"--'l

,(n^4-/-4 n t - Q<> q^, hnnrl., ,*ZJ'

'

fr,r*,u. fu:

a-t' l; Z' ^ / . z-'J"a' 'J'-^4

\

, V y..*,-t' ^b +-:C r

y-:f-ft,,b / L:fu .u(,*T.W.

kt' Soo-Ju, , { r, irtt C;"-*

,;^A, J,lo USltu ,'' oL-n-u,,.)

31b L) S 1o i

s-i? FLJ iss,l Lt Sv 5.Ar-! f).*"1

L (A c-,<--,- f x ?^^^L*a

ffi'11:::lruVjJ3l .-mffi,*.

Lsl FrJ ttrz CA

*-n^-.,^ /-1,r "-J^^.-Z-/*^fu1 / /*4^-r-*-

CA-^ -4-1 1 ^^-,*.^7 ,*4

(/^""-*-r- .Lrn*n^/

.)

r^."

ftlo (7st

,-*^-/-a -r,r-4Ut4b *f'9

a/*-,-r-^/A" e<-o

//"^7 1, S;/,r.*- f|"/qr*- H *-/-/ C"^a^-

3.( i {LJ LbL *^h/.^'r'l 3t>1JS{tY

[-".0

IM ,{#x't: f^.*-^--^/ ^qa" ?*l I

h k-.^--( m uft./ dtza ^*ia-A--*,f *ff--* -*'(4 a-@

Y

,/)

a)n/)r--'?(i-^.f /" '/ [3^*A^-^,*-a ?-r.,.rti,-.-,*u^^tb A

Ss's- F,rJ tlGLl -(lJC^,(1n)

/t-.,a^ e<,.thr-,-., .,^---/-.^ 6qn^^- ( /*- 0^l-/L-/t eea 'L-a)f-y-., ,/1-\*.\-4-L-\ - rl<^ U I n5 \-,(ALl

*b ,t-M */ ;*^ /L",-- -) L) /"r-"..-^16"- ,. t1

*, ^ ",0 .r-^*rL.'. 1, ,e-J, 4^-G ,1r*, 4- , - ,, ,(--.-DfuP v*&o 1' ,Lb-^-.-.^.* --,(A

tl f^.'fu "'u^-J"^trf4;

O t'0;

(s '' c",-

K"- ii-*dJ /^-or-* Lu----",

//'w-.^-U-,., ^,

/,rJ

Tlv'^ (' c o

/4ar- A-A"<-L'\

,/1

' Lru-<-t-ryttzZ

6'z.r €rJ Lsr

tlso)

ftt t*-rdz

qw(1*:43ffi ',q:

ory^, (llZoy ,/al th **V, fV W ta /

",a--,,'vfr Yg ttll

n27oL mfo \pwqt

rffiir) 0 Y|ffi ryOW flfrnyrun'Tbffi ruV

W r-/ \/4.r."r-r-il4 fV

zoL

ryWfry '

*r.-tr-V^afi W .bI

tr*D w? twT

-. J aa^-t-a v*t on

*l \.-;t/:--,Vy1y-g

Zos_/ og

h"'r..r*ry"

toh- tol 'f -? 'd 'r"J

ry w -n--t^/v o,Qv

,t7% --r r>n-Yr* q e-X*r[)F-''uru VV) 4

Y*@*7*ryH'r'n"

,1

n^ ziz/v) yfu-y"---7 *2,

rqw baPryq b

(/ @;/v ;2,-,v **T

€, t)l o -rm

-YvA7ru ry ry,*f

")[

q?"#

Vr*lfl

llLbD lzqC{no *,,W, 77MA39nW ryry,\ ? ',,ry

f,.q' 4W %ry*ry

Y-T'@)(>Fo* trry w

-,%

*ry

fVryY -"+"r-, -44w ry1r_ t/ **ry (:)2o3 Ary

Ltt

W>\dffiYM W

Wt "\gr@

fP m, fe n/"'t^/ ry frnry"t

'/d 9* - 693 d) LsntroS

\"1)l o*

Xah'Z'/ 'j"W-<-nT*@o@\-de"*U *

fW,r,ry-'-" Tw @r"A WnsSll

^* : w,941 O(e e ot 5l,I

at Ytvy*t frt \f ^ (*{ ,ipd @

,;,#,V' ; 7utry)sos

N, -*-"^--ar*-

no' d' bl.lte

' try1P r *5,-r"7 %f{/V

I f-Ll

yfp '\r"lr?6 Yl- v*4 W

, oSbl

^ ^"d <r9/5nrr e'%_l so'ru/'''DnrurPr' "J^ a 'r ,;r&

fryyg ryvry)4 /1 'ry T,

ry w ry r'cvry^"fu%W_* ry *t

(t1t hz'?h,'()i?Z ?)Nve)A;i ?rtt-|1k

v' wl\

7v+uy17^YY- 4l

)S,,r -r z L-n-,rz^.,iT7) o i tr d-,t

o1,t d n7'Y'

.a L'ut J

//

-f ^.V- ", 'ny'

u

,4o.*.?utrt-r-r,/ ,W % ProtT\.

,t*,--,u--ttf ^b TW"_p",

+,tur , ')T.^o'J /-' e rJ-rnTftl

'(il'*rl7 i Zvyv t-.-an/

1'x"2"""-t--tr|M

t

vvo (glQllab .Y*-7Ln ry. f**"V -$ bLt t

aLtl

@ f,*ry,"f ru rvra *,n

rlT GV" a\4

ryWP zvrtv

V*ry (yy 4 rry-*ry+"-e

-Y q#-vb' ry -t4/4 ffi

_ dn^d,r

- tl \t

(ral,t A

05 L W 0-,o

(,uu, Y qs) shL %r{ruru re

bLS l-,0

a ws) ht-s

1"^T;"v

(\ry rrrua

6Ut *+tt >s)

(,,t, 2h9

^'*-L

w"t)

"75

) LOSffit ,a,ry@

g, L 'L

r (7)) Yb

?14.1fYTvY )J

1) b Tn_)

%lj

H-T@

rT)o

b l-,q

,,\ Mq @

4,3

Lt,tt

-7a

()(rzo) wA

aryw@

o

\-

b l+>ryvz4 n

l) {'';6 1L

zz / A>J *y

btv€q,s lN a ha sDse), w^-ryry1

rfryV*T-'v ,

i ,',,t ln,'

n(' 9,'

ffi#(,,

( L -rph

t t-t, J t L h

(tcbl a y+

/Lh p,L?-

zAz av);

Sqr

'Lit Fr. p1 L,

01 '12'S'n 5)h

? *r,rl

)

o5 ,j *4^/

,. qfulJ

-W."ICJ

(tr-at 12 f ") LL f, J LL/, I

2 ,:u-rov */ (f,-r|r,J n *VH

ll

n ^q'"f'T-5- n4

ry* Ar-f f"^.)br, ,--a7,,--^/a TV?

^.-+

fr]ruwfllu '

l*x /N

ff*"-'.' ,y q Pib*-+

s5r -15) ' hst fo ) h\h

i

/ uTytallz-lz=T

tr7th '/'.'-r'1-ryL--

fug

"9-"*rAlaS &LSl ,ta{ 'h.q,\/

W\wry -2

nn*uq *n=.,^ v^fw-'rto7

y; /tiffi';'-A szl e

n @'f"'-" W +7v"yy'*t

'rr.ffi arHt*ru]

il

lt.'';-

'l

t-,Ll P'') stsi' "vf .r

@v@1 _"@Tr3rWW"')

4y6^-^)ff-)/fry) 4-9^S yy*l-*r- 2 rTNr W Tffi,T4\l

frV---r" e{ 0 -*?ry+z7o e{ n -r1/Z 7.,'v'vfrul

+1-*-L-:l ,, %) qryQ

- .,

fqb^ry?. y, l?-rr-a-;Jvv vffW,Y?.,.?

\ \#t>ar-P;trJ \- V,Wn

'rag'r'i$1,1M

W

,/ '.J' , /'

(rtt ^zt)ri'.r-)i"jrq, u a\ #,"*lr*) A'&{S.wy(,

*gg-*-'-go F7 r\.4/t- fT- ,f

fu Ul ,l^ 1-t-to

"Hr*4 ,7imY7ry) fuTft y rr*<rrrt 'T-,YO ) n:,

uvls

-)

-'' l*.-)L*,.. -^y' 0*T qa-.yr-d

T/f,l ? >tvvu? fr-*nq

*a4.t'Twt1oz ,\/b

d

o+ ' (vLwn)

-*7k??"

ar"ru

n w'Q

At/

f tL

nv-o y) q

gryl -'"14

I

f-"*W Lf+tu/

LZol 'f)'5 -2.o1 P'ru'ry W)

/'

(rYTFvL tsbl_)otL fni 7. 1?

- ,7 ,nd 4. T*'A ru,1/

t)'Lg

4d riVr*Vl

I

L u-;

t 7+ \l't

ga"fl # p-"...-?'P ;t W cl-''ru-v&a fl

ryn refu 'f./+--r"rr, + rrQ?u SSI a't VAI

l,.ffi%n,)ru_ffiaKfio7yryvl*ry;..fl'",J,, i,

( 6hbt)sA1 f?? L2

ll'Lt.l ' p 'S f,7 'Lo, 's 'n t>1, /'*)L

*V , -yC ile*ry 7 ra ":,*-*/ i,ltr /4 grynlq 'i

W y7"'"t *L Yq ,& rs/

Afrq4--t-rtTt rr-Ty$-// W i/+-: /#1 n'

'/- ' v

\,t--r/ L ' o?ur Q* L4 %tv+ r---"7, QrW i CS u

Tlv

Y7 "'"t

L sl

,I

, 'w l"*r& ,, )o?1 ') , v4,-1,-?,'r'v'\--4)cv

I

,i

ry""a +tzff-nt r,ru7-v-n AV ryA fn,

*{-WWl) zzLl.s v)s | , L . --,7*'v -vTr trr-n >r'i

Z y' no >-i'*1*rv+IJ +a,1 -/ o % o

i

v*'h?eq,-f, b* 3y9ryyr-,^--/,,-to,jt/ / o Y .a i/ ", toi:l

wffi'2w,',AVZ-n'

i

./'

, >1t-T ' c>-t1ay.y-p\ *t-yyl-Wt(--1,1. " V1Mln li

95)

.,-(M(-c)fu1(,tL/)LLsY9't;b,''t{ '2'?-l sn lhz /Wb cll,n ry? -'?b"4'A/ ry tq!2 %MwKWW

Q^fr?^r"" 4L 'fuvVqrrzVaf y ry y?44! k-n, ry

-"*rrr/-+? 7*'"-"/ o, 7at4 ,Q."fd V 94): yrym -V@ );44

Mr"*D,vyry*ry+"+S_ il

f'Td, Y (' ttt 'ry(t)

Lc-st]'mf^) e"t ffi,

A W,b4

tffi

€r, 2 ,"-S ost ? ? ) --s L-r Q:f*rl ^ YT\ i

,;ffi

v:/>4: p.*r-n, U'-**, **! '4ffiru

yPI ,L".o,."---Fro T-'Yt'Yra +f4'W+a*f* ^4 fry-*r ) O

.4

--->-L*yT?v g? trrJ*7/,'rr-r7rz'>--And r--?,W>@ a{ r*-..-";J dV ry rhv v7u'a'"rv

5i)

% rtz-t -,zv*) z-fu"t Y rA;r:ffi-;q

A<Vh:z q-YT\-11. ?-y' WZt'ry

q-t -1-V )

,I

I

I

I

I

1

I

Ls?'.r? pK ) sl/-

"*-4J'W rcV

'f7'*7-rv'v"Y1/ D

,2. u; qful

n2@

l,lbt *) .-s t l'","-5 *S

w,vry%%f,

Cr(W q &dryr. ',1

(rtb/ g f-z) 1o?l f",-j hb1

ilil

il

7 11/ @

:' h1';1. :1'

.t:

tr

t

tc.tt-tot ilr:, r, rta, rt"'r'rrr--trtr

Yto llt 9.qpa.r{(9t-t '^.u) L mru Ivrpu&

'Dtg-'ox ttPou (trod4tu.tl 'lc{iutlfl't o lturlr) !ilotr,

I

ruonr! .tt||lrlF pu! tattt,ter,

?r.ofip 't olrlsnan@ t-rimddr fo OUoKEU r lt uuo, q$.m l0ll OO

(U. t /,,n trV

ry 28-8/-2 Vry -- tf) orfn

y7/'1vrt+vz Z*"q >*??fu)

_ ?""()

'Orr,Alt2u.W rulgptq-

")et

tfi, w@! 'tqwr(c aruro 'eurtlrr rol

dr-flYLUHSlmUr o]{v e}lEfiou

31Ulil:ll

/as Lt ' F)'i ) ol @u-Taq3w

'+rhT-ru

#

T op -aoe*W -Ct (r, or-E-

,y Tvry n4t rulV

ry

-teb-Q-S )o/

try gry 1ro1 p1 ,J sa?

-E-Ttz,-*-TqZ -FTf nT-rvetl

---(arrr-T-wa

\\

Y

Q$t a Y+,s) J,.-,TD

7*t

*ry

,TJry-O

\Ls P1-_i Lvl

-6**;v,tzfi :y *fl^rel*

:-safwv'VlRtr -->

vTvW)

IJ

j La>

- *tvrf "

*ru w f,r* 7'Y'ryt rq*/' ry)Y

I

:

,1 JHWN

@-l < L^r4 y+

W- /1 //

r{

'l O-?j P-7""*'t'7n e') olL o

(t sr,r q ot) s/,L P-5

M3 rury

W f*:'- + ovt rry),4L (--*r, t

\-ob/ -')Y') tbf bLz r3 +e1'o Y2 -*rl" '-?TI'i "5>W Wr'/-t u^*f...ry' W f-frr-

--'_. -[l u

-/ -''-*-'._ ' -'-.'\--

/ "--./

.//,/ \-

---.