Legal Research on Congressional Record S6511-S6517

Unannotated Secondary Research

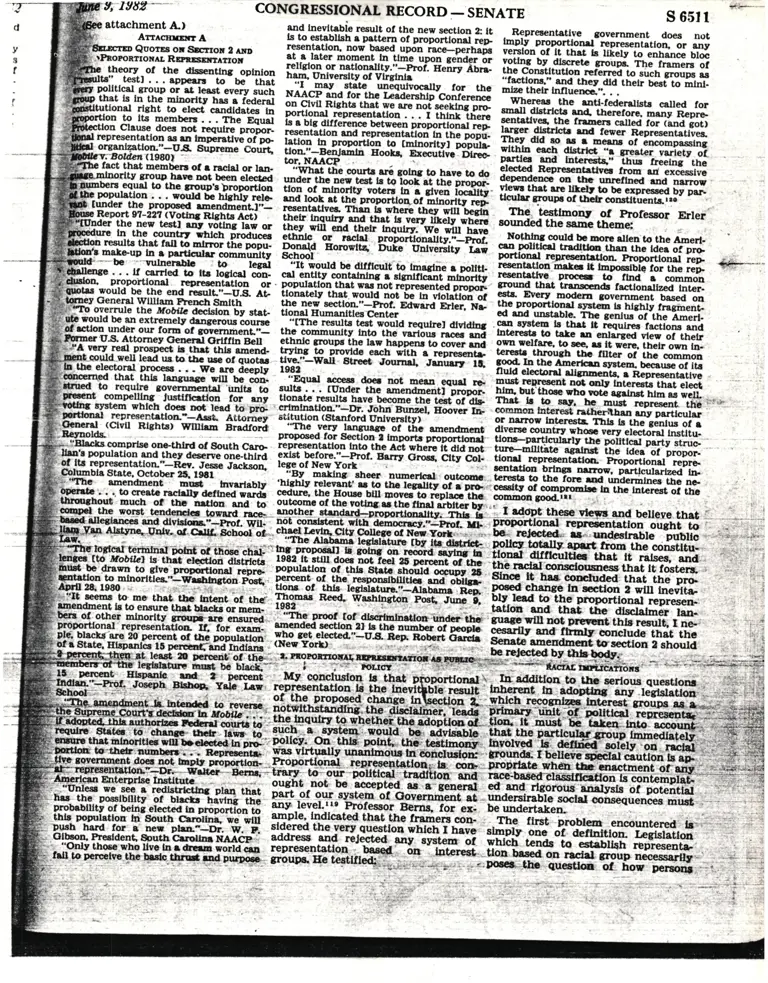

June 9, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Legal Research on Congressional Record S6511-S6517, 1982. 0d146a9c-e092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b1d3d039-7c3a-4f1b-bc93-53793e066352/legal-research-on-congressional-record-s6511-s6517. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

”wk -...J‘ . ‘

; ...... legislaturelnnstbeb "

‘ " 15 percent

sure- to Change

~ * attachment A.)

‘ _ * Arracmsnrr A

4' .-. . .- -- 0110113 on Sac-nos 2 m

' Paoron‘rrormr. Emma-non

. theory of the Menting opinion

' 3..- ‘t’ ._ ts" test] . . . appears to be that

.. dates in

g. ‘mrtion to its members . . . The Equal

‘ ‘,’_. . tion Clause does not require propor-

a. , . representation as an imperative of po-

' g. organication."—U.8. Supreme Court,

:f -."Bolden (1980)

' 3' 3 . - fact that members of a racial or lan-

' i. u oority group have not been elected

:mnnbers equal to the group's proportion

" the population . . . would be highly rele-

- [under the proposed amendment.1"—

4- w Report 97-227 (Voting Rights Act)

‘jmnder the new test] any voting law or

. . in the country which produces

’- :fiction results that fall to mirror the popu-

*‘Tfiflm‘s make-up in a parucular community

u _. ~ ~ be vulnerable to legal

" Feballenge...ifcarriedtoits logical con-

n'r anion. proportional representation or ~

-'-_'quotas would be the end result."—U.8. At-

}; ? tin-hey General William French Smith

yeti-(fro overrule the Mobile decision by stat-

. on would be an extremely dangerous course

in! action under our form of govemment."—

' tamer US. Attorney General Griffin Bell

,_ “9A very real prospect is that this amend-

- “v -- —-t.,could..well lead us to the use of quotas

’intheelectoralprocess...Wearedeeply

concerned that this language will be con-

,J?'atmed to require governmental 'units to

' resent compelling instillation for any

:‘3’ . ...- system which does not lead to pro- ‘

‘ portionsi representation.”—Asst. Attorney

“General (Civil Rights) William Bradford

.3 ,Reynolds.

-" ,. ‘fBlacks comprise one-third of South Caro-

.1 lian's population and they deserve one«third

"of its representation."—-Rev. Jane Jackson.

Columbia State. October 25. 1981

~. 2- “The amendment must. invariably

. ‘Operate . . ._ to create racially defined wards

=,throughout much of the nation and to

‘ écosnpel the worst tendencies toward race

'. » . ' :rallegiances and divisiosm.”—Prof. Wil-

’ , Jan mummies“ School oi ..

‘ I

'-'~ ‘. ff'l'he'logical Cer'niinal‘polnt of those chal— ’

lenses [to Mobile] is that election districts

,‘ihust be drawn to give proportional repre-

~'_' ; mutation to minorities."—Wuhington Post.

- Anti! 28. 1980 . ' ‘ " - -

r-

3 41: seems to- me that the intent "or the"

ff amendment is to ensure that blacks or mem-

-‘ bars of other minority mare ensured .

. . proportional representation. If. for exam~

7 pie; blacks are 20 percent of the population

"_ of a State. Hispanics in per-ecu? and Indians 1

,Jt least 20 percent‘of the-1

Hispanic and 2 percent

- 2‘ m"_—Prof_Joseph Bkhon. Yale Law

I i' m. . . thintended to reverse.

i gnmmm‘smmn Mobile...

‘ Wamhoriseshdaflcourtato

— then-.rlawst to‘

v_e government does not ban!) proportions;

_ _ 1..“represeutati0xaV—Dn—I-rwuterw—Bermr

American Enterprise Institute .

‘ probability of being elected in proportion to

this population in South Mina. we will

. Gibson. President. South Carolina NAACP 5

' -‘."~ - “Only those who live in a dream world can

.fail to perceive the basicthrun andpurpoae-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD _— SENATE

and inevitable result of the new section 2: it

is to establish a pattern of proportional rep-

resentation. now based upon race-perhaps

at a later moment in time upon gender or

religion or nationality."—Prof. Henry Abra-

ham. University of Virginia

“I may state unequivocally for the

portional representation . . .

is a big difference between proportional rep-

resentation and representation in the popu-

lation in proportion to [minority] populm

tion."—Beniamin Hooks. Executive Direc-

tor, NAACP , , ‘

"What the courts are going to have to do

under the new test is to look at the propor-

tion of minority voters in a given locality‘

and look at the proportion of minority rep-

resentatives. Than is where they will begin

their inquiry and that is very likely where

they will end their inquiry. We will have

ethnic or racial proportionallty."—Prof.

Donald Horowitz; Duke University Law

School

“It would be difficult to imagine a politi-

cal entity containing a significant minority

population that was not represented propon

tionately that, would not be in violation of

the new section."—Prof. Edward Erler. Na-

tional Humanities Center

“(The results test would require] dividing ,

the community into the various rams and

ethnic groups the law happens to cover and

trying to provide each with a representa-

tive."—Wall Street Journal. January ll.

1982 .

“Equal amass does not mean equal re-

sults . . . [Under the amendment) propor-

tionate results have become the test of dis-

criminationf—Dr. John Bunsel. Hoover In

stitution (Stanford University)

“The very language of the amendment

proposed for Section I imports proportional

representation into the Act where it did not

exist before.”‘Prof. Barry Gross. City Col-

lege of New York . » '

“By making sheer numerical outcome

‘highly relevant' as to the legality of a on»:

cedure. the House bill moves to replace the

outcome of the voting as the final arbiter by» .

another standard—proportionality; .This is._

not consistent with democracy."—Prof. Mi-

chael Icvin..Cit¥ College of New York; . . '

“The Alabama legislature Lb! indistflctg .

mlproposalliigoingonrecordsayingin

1982 it still does not feel 25 percent of the

population of this State should occupy 28

percent of the responsibilities and obliga-

tions of this legislaturs."—-Alabams Rep. ‘

Thames Reed. Washington Post. June 9,

“The proof (of discriminationunderthe ‘

amended section 2} is the number of people

who get elected."—U.8. Rep. Robert Garcia

(New York) . - . ~ ~ .1: . ;

o' .

o

' . . mu

My conclusion is that p’

representation is the inevi

of the proposed changein‘

notwi .the-'_ ' _ ’erfleada

the inqmry to whether‘ths adoption oi-.

sucha systemkwould

pox-tional ‘}

ble result

Proportional ”representation-u is. con-2.

teary to? our-political ‘ on_ and“

ought not be swepted as va‘general

part of our system of Government at.—

any level.l 1' Professor Berna. for ex-

ample, indicated that the framers con- .

address and rejected any system of

representation ; bued on interest.

groups. He testified; »' ,.

a. monstrous Won :4; Myra-say

tion a; '.

. be advisable. \

.. policy. On this: points-the testimony

was virtually unanimous in conclusion: '-

'.

$6511

Representative government does not

imply proportional representation. or any

version of it that is likely to enhance bloc

voting by discrete groups The framers of

the Constitution referred to such groups as

“factions." and they did their best to mini-

mize their influence". . .

Whereas the anti-federalism called for

small districts and therefore. many Repre

sentatives. the framers caUed for (and got)

larger districts and fewer Representatives.

They did so as a means of encompassing

within each district “a greater variety of

parties and interests." thus freeing the

elected Representatives from an excessive

dependence on the unrefined and narrow

views that are likely to be expressed by par-

ticular groups of their constituents.m

The testimony of Professor Erler'

sounded the same theme:

Nothing could be more alien to the Ameri-

can political tradition than the idea of pro-

portional representation. Proportional rep-

resentation makes it impossible for the rep-

resentative proce- to find a common

ground that transcends factionalized inter-

ests. Every modern government based on

the proportional system is highly fragment-

ed and unstable. The genius of the Ameri-

can system is that it requires factions and

interests to take an enlarged view of their

own welfare. to see. as it were. their own in-

must represent not only interests that elect

lum.butthosewbovoteagainsthimaswell. _.

That is to say, he must represent the .‘

common interest ratherw'than any particular

or narrow interest: This is the genius of a

diverse country whose very electoral institu-

tiom—particularly the political party struc-

ture—militate against the idea of propor-

tional representation. Proportional repre~

sentstion brings narrow. particular-iced in-

terests to the fore and undermines the ne-

ceasity of compromise in the interest of the

common good."l

'. I adopt thwervieys and believe that '. . .-.. ..

proportional representation ought to ’ _ .' - '

be. rejectedi an». undesirable public ' ' w, ‘ *

policy totallymrt from the constitu-- - w

tional difficulties that it raises. and

the racial consciousness that it fosters. - .

Since it has concluded that the pro- . :

posedchangeinsectionzwillinevita- ‘

biy lead to the proportional represen.

tation and that the disclairner lan- .

mwmpotpreventthisresmtlne- ‘ '1 r

cesarily and firmly conclude that the ' =', .

Senate amendment tosection 2 should -‘

be rejected by thisbody.- _ ._ 1'

7“” i . . ”has: i-..

In addition tothe serious questions,

inherent in adopting any-legislation-..

”WW ‘3 am “m” "‘

l5 ‘ "“3113: D0 .t » Emmanuel?» ’

_tlon.' it must be taken..into. account; In-

that .the particula; group immediately; 1'.

involved‘ls- deiined‘_solely *on. racial

grounds; I believe special caution is ap- -

propriate when the'enactment. of] any

racelbaselfchOn is contemplate

ed and rigorous analysis of potential i ‘

undersirable social consequences must - ' ' '“i

The first problem encountered isfi

. 'push M for ‘ new pun-4),. w. p. sidered the very question which I have simply one of: definition Legislation

which tends to establish representa-‘ . : , .,

tion based on racial group necessarily'~ - -;- 7* ;.

posesthe question of how persons y .4

- 7V. 7.. , x .0-

.. ”Wm: -.... .. .

v .

1-.— ; st—e—(;W-fl—-.’~F a?-

,:fi magawa-c'i“. .rhvéu

sit-rt“.

r!”

4,...—

"'1tr‘ _ 0-. . . .

.4»

amla'va'pl,vrflu .xmw-‘hrma xvi“ --v

-4 -

- mum;

i

.-.‘ ~ .~

'nhc-vhg-uoutw

4'

, ___ racial characteristics;

ful assumptions which are necessary v-

S 6512

shall be assigned to or excluded from

that group for political purposes.

Recent history in this and other na-

tions suggests that the resolution of

such a question can be demeaning and

ultimately dehumanizing for those in-

volved. All too often the task of racial

classification in and of itself has re-

sulted in social turmoil. At a m

mum. the issue of classification would

' heighten race consciousness and con--

tribute to race polarization. As profes-

sor Van Alstyne put it. the proposed

change in section 2 win invitably

“compel the worst tendencies toward.

race-based allegiances and divi-

sions." l" This predicted result is in

sharp conflict with the admonitious of

the elder Justic Harlan who wrote in

Plessy'

" ‘The‘re‘is no caste here. Our Constitution is

colorblind. and neither knows nor talents

classes among citizens. . . . The law regards

manumsn.andtakesnoaccountofhis

surroundings or of his color when his civil

rights are guaranteed by the supreme law of

the land are involved. m

More recently Justice Stevens called

the very attempt to define qualifying

[Blepugnant to our constitutional ideals.

.If theNatiouloovernmembtomahe

a serious effort to derine racial class by

criteria that can be administered objective-

ly. it must study precedents such as the first

regulation to the Reichs Citizenship Law of

November ll. 1935*“

Thus. I find‘that the race-based as

Signment 0f citizens to political groups

is a potentially disruptive task which

appears to be contrary to the Natim’a

most enlightened concepts of individu- .

al dignity and civil rights.

The second problem involves doubt-

tosupport a racebased system of rep!

‘Fresema'tion; The acceptance of a racial

~—~-—gronp- as a political unit impliem W“,

-A—_"

Zia-mu

one thing. that race isthe predomi-

nant determinant. of political prefera

eme. Yet. there is considerable evi-

dence that black political figures can

win substantial support from white

voters, and similarly. that white candi-

datm can win the votes of black citi—

zens. Attorney General Smith de-

scribed the evidence. He referred to

Winn that blacks will only

vote‘fbr black candidates and whites

m- manly for white candidates andsaid:

That.0f oourse.iauottrue-0noof.tha

bestcxamplesofthat isthe city of LosAn-

“f; otbmnsewan

timonyr

I question whether. a black can be fairly

represented only by a black and not. for ex-

ample. by a Peter Rodino or that a white

can be fairly represented only by a white an

not. for example Edward Brooke. '“

_ In otherwords, thereis no- evidence

that racialbioc votmg is inevitable and

reason to doubt that fair repredenm-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE

tion which assumes the contrary may

iweif have the detrimental conse-

quence of establishing racial polarity

in voting where none existed, or was

merely episodic. and of establishing

race as an accepted factor in the deci~

sionmaking of elected officials.

Finally. any assumption that a race

based system will enhance the political

influence of minorities is Open to con-

siderable debate. Professor Erie: testi-

fied that it is not always clear that the

interests of racial minorities will be.

best served by a proportional system:

It may only allow the racial minority to

become isolated. The interests of minoritia'

arebatservedwhen narrowracial issues

are subsumed within a larger political con-

text where race does not define political in-:

teresia. The overwhelming purpose of the. .

Voting Rights Act was to create these condi~

tions. and probably no finer example of 16K?-

islation serving the common. interest can be

found. But transforming the Voting Rights

Act into a vehicle of proportional represen-

tation based upon race will undermine the

ground of the common good upon which it

rests. Such a transformation will go far to-

wanh precluding the possibility of ever cre-

ating a common interest or common ground

nsideb

Promssor McManus recalled an in-

stance where politically articulate

blacks argued strongly against propor-

tional representation: ' -

One faction of blacks. led by several state

representatives. the three black Houston

City Council members. argued for spreading

influence among three commissioners

on

togeth er in one precinct and

elect a bhchto tosit at the table and watch‘

the paper-ally up md down " he said Wash-v

ington arguedthat packingan'the blacls in

one district wm “not in the best lanterns:

interests of the community. "I“ -

The city attorney for Rome. Ga,

Mr. Brinsomsimilarly observed; _ ‘

3, our, in preceived as uniform

proportional representation aitm

a group’ a participation in the political-m proc-

’ mes. in reality it may well frustrate

the camp's potentially ul efforts at

influenm on. the poliflcal system

A third problem relates to the per:

petustion- of segregated residential-

patterns. Since our electoral system is

established within geographic param-

eters, the prescription of racebased

proportional representation means

that minority- group members» will in-~

directly be encouraged to reside in the -_

same areas in order to remain in the

June .9, 1.982

premium would be put on segregated

neighborhoods. Professor Berns used

the term “ghettoization” to dmcribe

this process. “If we are going to

ghetto-ize, which in a sense is what we

are doing, with respect to some groups.

why not do it for all groups?" I“ Pro-

fessor McManus emphasized in her

testimny that administrative practices

in the context of section 5 seemed to

encourage Such segregation: ~

A premium ls piston idem racially

homogeneous precincts and nail: that as

thetest. anditseemstomethebmmline

racially

cinctaistheoptimalsolutimctheideal.

xhichlflndveryhardmawept-acifizen.

I reject the premise that. proportion-

al representation system in fact en-

hance minority influence—as opposed

to minority representation Even. how

ever. to the extent that this were a

valid premise. it would be valid only

with respect to highly segregated mi-

nority groups. Indeed. proportional

representation systems would place a

premium upon the maintenance of

such segregation. Porto the extent- ~

thata minority group succeeded in in-

tegrating itsefl on a geographical

basis, it would concomitantly lose the

benefits of a system. of voting.

Such a system ould benefit minor.

ities only insofar as residential segre-

gation were maintained for such

groups. .

Thus. analysis suggests that the pro- '

posed change in section 3 involves a

distasteful question of racial clasifica-

tion, involves several doubtful assump-

- tions about the relationship between

_,.race andpolitical behavior and may.

feucoura’gcpatter'usolsegren'mthat '

are contrary to prudent publh: polky~ -

-~Theee likely undedrable- anal conse-é' A

oneness argue strongly Vagina: the

propom change in section a .

Inotewithlntemt thermrlrsin.

the New York Times‘" recently by

my distinguished colleen)! from

Maryland. Mr. Mamas. in which he

observes that the common interest on

' the part of proponents of the intent

While the proposed amendment to section '

”mm?

" amerith an

standardisthatweallwanttocreatea

“homose WM; Party”;

motto my friendfrfinr’

gthissideoltheisue; ”“. “ ‘ “3‘:

Tne'naw in the argument of a?“

penis: of‘the‘ results test k' Eng:

3,35“:

plies that the decisions of elected 0115-: info-es any arguable bloc voting é‘yndromgaaf confuse thecoweptof mm renter

- -eialsa1epredominantlydetermined_by I!!! We!!! whom! member: lronzexerus sentation with.

emmssmmmmmmmmmm.

V :5 individualsorliispfleindivkhmlsor‘

Aleutian individuals on a city council

lemmas?

While WWW to be meow,“

WWWd W

or county commission or school board.

.theytotallyfailtoreccmminmy

view. that this may be entirely incon-

sistent with the idea of

, maximizing-

blaclr or Hispanic or-Alentian mm.

ence enthuse representative bodies.

The proportional W

tion defends on racial identity. legish- race-based political group A political prennseonthe part of my colleagues

‘3“ 3i.-

.ynr

.June 9, 1982

g; *‘i "on the other side of this issue implies

.eof course. the creation of district or

» ;" éward systems of government through-

xii-out the country in place of at-large

‘54. systems. as wellas other basic changes

qtructure. In a community with a 20-

.- percent minority population. and 10

7,. city council seats, this. it is presumed,

c.‘ will be far more likely to insure 2 mi-

; nority rcpresentatives than would an

at-large structure.

““That may well be true, although I.

am far more reluctant than results

proponents to assume that minorities

will inevitably elect minorities to rep-

“ resent their political interests. I reject

the idea that only blacks can repre-

sent blacks or that only whites can

represent whites. In any event, the

.. logical outcome of any ward or district

.- system designed to insure proportion—

”' ate racial representation for minorities

is that such minorities will. in effect.

be clustered into what amount to po-

’ iitical ghettoes. We will have two dis-

». ‘ tricts in this community with heavy

. ‘_ concentrations of minority voters. and

may well elect two minority individ-

uals to the representative body.

0n the other hand. unlike an at-

large system in which all lo council-

men would have to be responsive to a

large degree to .minority interestS.

under the system designed to promote

a proportional representation. there

' would be 8 councilmen who would not

' have to pay one iota of attention to

minority interests. Potentially success-

ful efforts at coalition building across

racial lines would likely be blunted as

racial lines were reinforced and em-

. gr phasized by the proportional represena

v’ '~v-;tation_ system. The requirement of .

what. in effect. amounted to a quota

.. system or representation would tend

‘ . "strongly‘to

nor-ities by departmentalizing the elec-

torate into black districts and white

districts and Hispanic districts and

‘Aleutian districts. Minority members

" .. might well have more members of ;

' their race or ethnic group sitting on

, . city council. but their opportunities

; for exercising influence on the politi-

‘ cal system outside their districts might ,

IToo‘k”'at the House of'RepresentaoT-f“

~ ~tlves..for example. and note that there »

is' an..18-Member Black Caucus. I did‘,

just}, bit of research on this matter

and noted that. on the average.

tion in excess of 80 percent. Now. if

'were‘a Membervoi the caucus. I might

-welLbe delighted with this state of air

.‘fairzi‘I’Wwouitlove to

. that was nearly totally homogenous in ,

' this respect. 0n the other hand. I

question seriously whether minority

influence as opposed to minority rep-

resentation is maximized by this state

' of affairs. Might not, for example. the

eminority‘ community. in Detroit be

», better represented in Washington or

Lansing if there were three minority

districts of 30 percent each rather.

bolate and stigmatize mi-.-

haveaaiistrict~ shipin mam

terests

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE

than a single 90<percent minority dis-

trict? Might they not be better repre-

sented even if they had fewer repre-

sentatives who were black or Hispanic

or Aleutian?

Senator Marinas is absolutely

wrong, in‘ my opinion. in his sugges-

tion that opponents of the results test

oppose it because of their interest in a

“homogenous” Republican Party.

While my own primary interest in this

area has nothing to do with partisan-

ship one way or the other—and is pri-

marily related to constitutional con-

cems—I would must that if a homo-

genous Republican Party was my ob-

jective. I would be delighted with the

results test. I am. however. not inter-

ested in this. .

I would be delighted if that were my

interest with the opportunity to have

tidy, little districts. in which all the

minorities were concentrated. I would

be delighted if I was interested in a

homogenous party to have tidy. little

districts—but many more of them—in

which nonminorities were concentrat-

ed. I would be delighted. if that were

my interest. to concede to minorities z

or 1! number of seats and be able to-

focus the attentiom of my party solely

upon the rest of the seats. I would be

delighted that I would not have to

start by calculations in each distict

with consideration of what must be

done to maximize submit. or minimize

opposition. from the minority commu-

nity. .

In other words. if one's interest were

a homogenous Republican Party, I can

think of no better way to achieve that

thanbyremovingwhatistodayapre-

dominantly Demoaatic voting group

outside'the boundaries of 80 to 90 per.

cent .of the dish-lg: in the country and»

conceding them a measure of prODOr-'

tional represenunom’l would M’de‘“.

lighted. if that were my interest, with

the ruleof the Justice Department de-

veloped in recent years that a district

one» “likely to eled a minority repre--

sentative." I would be delighted not to

have to start each and every congreo

aional or State legislative or city coun-

c'ause' of thd'psesence of ‘a’ minority

group dispro attracted to

mypartisanowosltio ..-: -.~ . .

Howeverrnoneot is my interest

. nor." as iatulhnw. the interest of

anyonerelsr r the. Senator.

fromMaryiandonthisiasuerimply‘

do not accept the premise“ the Sonar. L.

or that‘of the civil rights leader-w

when narrow racial concerns are given . » »

. nent. a political subdivision which was

proCess. Ibelieve insteadthatitisin.

tor.

, of W

predominant rfoem» in the electoral

the best interests of minorities—all mi- »

noritios—that racial and ethnic con-

cernsbesubsmnedwithinafariarger

political context in which race does

not definepolithl‘ interests. in which

the two are not Wt. . - —

posed change. in section 2,.would apply;

. “an"

. ment. and which made no changes in 5 ‘~

S 6513

How could the idea of racially identi-

fiable wards or districts ever be looked .

upon as a civil rights objective? Has

the civil rights movement evolved so

greatly over the past decade that all ‘

hopes and ambitions of ever achieving

a colorblind society have been discard-

ed? Does anyone hold the slightest

belief that results or effects analysis

will do anything other than intensify

color consciousness?

How could the idea of a 10-year ex‘:

tension of the Voting. Rights Act.

adopted by the subcommittee and

which I continue to suppon. ever be -,

viewed as anything other than the 7

highest affirmation of civil rights? It. '

was considered such only 1 year ago. It

was only a year ago that Vernon

Jordan of the Urban League said of

the act that. “if it ain't broke don't fix.

it." It was only a year ago that Benja-

min Hooks of the NAACP testified in.

the House- ’

We support the extension of the Voting

Rights Act as it is now written. The Voting

Rights Act is the single most effective. legit:

lation drafted in the last two decades. I have

not seen any changes that were anything

but changes for changes sake. It would be

best to extend it in its present form)“ ' '

I understand that political positions“

change and evolve over time. but. I.

simply do nomgt- as credible that-

the position ously endorsed by

the civil rights community less than a

year ago now reflects an-"anti—clviL,

rights“ position. That. is not the intent -

of anyone that I know- who oppom

the House measure. ~

”Vansracrorsnmons: _-l >' Y

Assistant Attorney General Remi‘

oldshemphasiud _ in ,his testimony; ' ‘

before the subcommittee that the mgr—7+-

nationwide..,would. apply to existing

laws and would be a permanent provlsf’ ”‘7'?"

sion of the act. These‘ observations co”. ‘

gently establish the parameters for new. . 3

ceasing the practical impact of the pro-.5 '

posed, crime in section 2.1?! ..'.-’.,iii

Every political subdivision in-- that

United States would be liable to Mme ,

its electoral practices and procedures - -

evaluated by- the proposed results test:

of sectionfi-jkisimportant to emptiness;

size at the -that~for'Wo£E::-*

section 3; the term “political subdi ~'

_ encompasses tail is _ ..

n-‘nflzmlr.

subieot mas aura». as «an; ;

subsequentlypdoptedflm in? who?

not in violation of section 2" on the'efifi “—1-

fective date of the proposed amend-

its electoral system. could at some sub-!

sequent date find itself in violation of" _

section 2 because of new'ioeat canal-3‘72 . .. -‘~;:'

tions whichmay not ho’v'rI-bfconm”

n-u—m s

w';fi=f‘:’~.’~

. 4w...

:‘xEL-é-r

s 3—...

" ities.

S 6514

plated and which may be beyond the

effective control of the subdivision.'"

Within these general and far-reach-

ing parameters.”7 it appears that any

political subdivision which has a sig~

nificant racial or language minority

population and which has not

achieved proportional representation

by race or language group would be in

Jeopardy of a section 2 violation under

the proposed results test. If any one or

' more of a number of additional “obiec~

tive. factors of discrimination" "' were

present. a violation is likely and court-

ordered restructuring of the ehctoral

SYStem almost certain to follow.

One witness' remarks are eloquent in

capturing a sense of the potential

breadth of the amendments to section

2: It is no overstatement to say that

_. _, the effect of the amendment is revolu-

tionary. and will place in doubt the va-

lidity of political bodies and the elec-

tion codes of many States in all parts

of the Union . . . The amendment to

section 2 will likely have these conse-

quences: First. it will preclude any

meaningful annexation by municipal-

government consolidations.

county consolidations. or other similar

governmental reorganizations in areas

having a minority population. Second.

it will outlaw at-large voting in any

area where any racial. color. or lan-

guage minority is found. Third, it will

place in doubt State laws governing

qualifications and educational require-

ments for public office. Fourth. it will

" dramatically affect State laws estab-

lishing congressional districts. State

legislative districts, and local govern-

ing body apportionment of districting

schemes. And fifth. it will place in

doubt provisions of many election

; codes throughout the United Statearz :7

The probable nature of a section 2

order ls'iifustratedby the actionof the "

" district'court in the Mobile case.“'At

the time the action was brought, the

city of Mobile. Ala. had a- city commis-

sion form of government which had

been established in 1911. Three Com-

missioners elected at large exercised

legislative. executive. and administra-

tive power in the city. One of the com-

missioners was designated mayor. al-

though no particular duties were spec-

mmmm-d mamma-

' court disestablished the city

sionandanew famofmunicipatgow-

comm

ernment~warr subwtnted consisting of

_ amayoranda nine-membercityicoum .nia.

-uwellasthetactthatclear,nmraeiar

-.instification- assisted for this yet-large,

system wait considered largely- irrele-

. vsnt by the lower court. Thua virtual-

ly none of the original governmental

system remained after by

the. district court. The conflict be»

tween the district court’s Mobile deci-

sion and fundamental notions of

democratic selfgovernment k obvious.

Particularly noteworthy is the district

' ebun's finding that blacks registered

'Missouri. New Mexico.

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD -- SENATE

and voted in the city without hin-

drance. Notwithstanding this finding.

however. the Federal court disestab-

lished the governmental system

chosen by the citizens of Mobile.

thereby substituting its own judgment

for that of the people.

The purpose of this section is to ex-

plore the far-reaching implications of

overturning the Mobile decision. Re-

search conducted by the subcommittee

suggests that in a large' number of

States there exists some combination

of a lack of proportional representa-

tion in the State legislature or other

governmental bodies and at least one

additional "objective factor of discrim-

ination" which might well trigger.

under the results test. Federal court.

ordered restructuring of those elector-

al systems where the‘ critical combina-

tions occurs.

There appears to be a lack of pro-

portional representation in one or

both houses of the State legislatures

in the following States with significant

minority populationsfl“ Alabama,

Alaska. Arizona. Arkansas. California.

Colorado. Connecticut, Delaware,

Florida. Georgia. Kansas. Kentucky.

Illinois. Indiana. Louisiana. Maryland.

Massachusetts. Mississippi. Missouri.

New Jersey. New Mexico. New York,

North Carolina. Oklahoma. Pennsylvag; '

nia. Rhode Island, South Carolina.

South Dakota. Tennessee. Texas.

Utah. and Virginia; ,

In addition. there appear to be addi-

tional “objective factors of discrimina-

tion” present in virtually every one of

these States. For example. according

to the 0.8. Commission on Civil

Rights. every State listed has some

definite history of discrimination)“

This often has been exemplified In the '

existence. . o! segregated. or,_a‘.‘dual’_'

school systems!“ In additiomwthe.

Council of State Governments has re- '

ported that Alaska. Arizona. Arkansas.

Colorado. Delaware. Florida. Georgia.

Illinois. Indiana. Kentucky. Louisiana

Maryland. New Jersey. New Mexico.

New York. North Carolina. Oklahoma.

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island South

Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee.

and Virginia provide for the cancella-

tion of registration. for failure to. to

a tt’ipm “objective factor of‘W‘

us on." Z: '

The councfl h also reported that

Alabama. Alaska.l Arianna, Califor

Colorado. Indiana. m

monthéfo‘ni elections. another typical

‘fobiccthrew factor-.4 01:17,. discs-1min»-

than“ anther. according to the

come“ such States as Alaska. Arkan-

sas; Calflomia. Colorado. Delaware. '

Florida. Illinois. Indiana. Kentucky,

Oklahoma.

Pennsylvania. Tennessee. Texas. and

Utah have established staggercdeleo- '

total terms for members of the State

senate. still another f‘objective‘ factor-

ofdiscrimination."1.“i " 7 . '

. Savannah, Ga; and Waterbmy.

June .9, 1.982

From the foregoing. the subcomittee

on the Constitution concluded that

there is a distinct possibility of court-

ordered restructuring with regard to

the system of electing‘members'to at

least 32 State legislatures if the results

test is adopted for section 2.1" (See at~

tachment B.) ‘

The subcommittee emphasized that

the three or four “objective factors of

discrimination” discussed above are by '

no means exhaustive of the possibili-

ties. Additional factors which might

serve as a basis for court-ordered

changes of systems. for electing. mem~

bers of State legislatures which have

not achieved proportional representa»

tion include: Disparity in literacy rates

by race. evidence of racial bloc voting.

a history of English-only ballots. dis--

parity in distribution of services by

race. numbered electoral posts. prohi-

bitions on single-shot voting. majority

vote requirements. significant candi-

date cost requirements. special re

quirements for independent or third

party candidates. off-year elections,

and the like. . '

AUMDHHBH a—smrs wane mm REPRE-

.‘sammnmoutonommmormsrm

“ LEGBWURI AND meson or "oeiecnvr

or Winn"

f:

l

I

minim [am

"i

w

€535

add-Mon. the guarantee»...

V In

lysed factual circumstances in such'

communities as Baltimore. Md; Bir“

vs; Pittsburgh. Pusan Diego.

Conn:

»_..'

as“.

.390

fin

" #1982

, uded that each of these com-

' faces a significant possibility

. £7: .. required to restructure their

-’ ’i ' of municipal government as a

“I of the amendments to section 2.

are discussed in greater detail in

bcommittee report at pages 154-

1 my additional views.

mesa examples are but a few illus-

of literally thousands of elec-

"5'. systems across the country which

I“ undergo massive judicial restruc-

should the proposed results test

wtedm The information present-

' dealt with state legislatures and

. .-.. : ties. but other political sub-

..; such as school boards and

r -.a dktrlctswouldbesubiecttothe

' judicial scruntiny should the

standard be adopted.

~ well aware that proponents of

results test consider this discus-

of the impact of section 2 to exag-

~ the situation considerably. In

the subcommittee would

First. the burden of proof in this

' _ rests with those who would seek

, r the law. not those who would

end it. Second, I do not believe that

‘ponenis of the results test have

..- convincing in explaining how the

;, would work in a manner: other

than that described in this section. In

if m where in the text of ER. 3112

-'V elsewhere is there anything which

udes a section 2 violation in the

- tances described in States and

municipalities in this section? Indeed.

g 4- e results test would seem to demand

violation in these circumstances.

i Finally, I am utterly confounded as

3 .. what kind of evidence could be sub-

.3 .‘ .. tted to a court by a defendant juris-

_ "- on in order to overcome the lack

-‘ .’._ - proportional representation. What

dence would rebut evidence of lack

efiproportional representation and the .

.‘exlstence of an additional “objective?

7 factor of discrimination? I have yet to

(hear a convincing response. In Mobile.

. "for example; the absence of discrimi-

natory purpose on the part of the city.

‘ r as well as the existence of legitimate.

3 nondiscriminatory reasons behind

their challenged electoral structure,

3 any . '11

.u-vs

:' -, at-large system. was considered insuf-

«um i . jg overcome the lack of propor-

,‘tlonal’ representation. y.we

:have been “reassured” that such can

gems are not well founded because a

court' would consider the "totality of

Woes. As noted in section-

begs the basic question:

E whiff. the standard for evaluating'

2'

(fly? evidence. including the "totality

osmotic." under the results

What is the ultimate standard by

deuce is before it? Apart from the

standard of proportional representa-

tionlseeno such standard.-

v'“couyaornas" mm

Because it has been characterized by

some as a “Compromise." I would like

to add Some additional. specific rec

marks on the Dole committee amend-

? merit. In what seems to be the euphoi

5,“ rm; n.‘

the following general observa- ‘

which the com W whatever evi---

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE

ria generated by the proposed compro-

mise. virtually insuring the swift en-

actment of this measure. I must reluc-

tantly state that I believe that the em-

peror has no clothes. The proposed

compromise is not a compromise at all;

its impact is not likely to be one whit

different than the unamended House

measure.“'

As much as it is tempting to embrace

this language and claim a partial victo-

ry in my own efforts to overturn the

House legislation, I cannot in good

conscience do this. As Pyrrhus said

many centuries ago. “Another such

victory over the Romans and we are

undone." Those who have shared, in

any respect, my concerns about the

dangers of the new results test may

look appreciatively upon the political

"out" being afforded us by the present

compromise: I would hope. however.

that none would delude themselves

into believing that it represents any-

thing more substantial than that.

The proposed amendment to section

2 contains two provisions. The first

provision is identical to the present

House amendment to section 2 dis-

cussed in the accompanying subcom-

mittee report. It reads:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite

to voting or standard. practice. or procedure

,shall be imposed or applied by any State or

political subdivision in a manner which re—

sults in a denial or abridgement of the right

of any citizen of the United States to vote

on account of race or color. or in contraven-

tionoftheguaranteeasetforthinaection

«0(2). as provided in subsection (b).

For all of the reasons outlined in the

subcommittee report, I believe this

provision to be dangerously miscon-

oeived‘“

The question then is whether or not

the second provision—a new er

of proportional representation—would

mitigate any of these difficulties and

improve upon the House disclaimer

provision. It reads:

(b) A violation of subsection (a) is estab-

lishediLbasedonthetotalityofeircum-

theStateorpoliticalsubdivisionarenot

equally open to participation by member: of

a class of citizens protected by subsection

(a) in that its members have less oppommiv

tythanothermembenofthcelcctontem.

mommmmmt

elect remesentstives of their choice. The

extent to which members a protected

class have been elected to o in the State

or political subdivision is one “cireunh

stance" which may be considered. provided

that nothing in' this section established a'

right to have members of a protectodclan

elected in number- equalto their proportion

in the population.

This new disciahner. in my view. will

be little differentur ilreffect fronLthQ

purported disclaimer in the House

measure discussed in the subcommit.

tee report)" Both provisions fail to

overcome the clear. and inevitable

mandate for proportional representa-

tion established in subsection ('a):any

differences between the House and

Senate disclaimers provisiono are

largely cosmetic. . _ 1.

S 6515

I will focus very briefly on the dif-

ferences in language between these

provisions and then rest upon the

analysis in the subcommittee report as

an expression of my views.

The compromise disclaimer refers to

violations being established on the

basis of the "totality of circum-

stances." This. I gather. is supposed to

be helpful language. It is not. There is

little question that. under either a re-

sults or an intent test. a court would

look to the “totality of circum.

stances." The difference is that under

the intent standard. unlike under the

results standard. there is some -ulti-

matecore value agaillst which to

evaluate this “totality. " Under the

intent standard. the totality of evi-

dence is placed before the court which

must ultimately ask itself whether or

not such evidaioe raises an inference

of intent or purpose to discriminate.

Under the results standard. there is no

comparable and workable threshold

question for the court. As one witness

observed during subcommittee hear-

Under the results test. once you have ag.

mattedontthose factors: what do you

have1WhereareyoulYouknowitisthe

oldthingwedoinlawschool: youbalance

and you balance. but ultimately how do you

balance? What is the core value?“0

There is no core vhlue under the re-

sults test other than election results.

there is no core value that can lead

anywhere other than toward propor-

tional representation by race and

ethnic group. There is no ultimate or

threshold question that a court must

askundertheresultstestthatwill

leadmanyotherdirectiommshorhit

is not the scope of the evidence—“to-

tality of circumstances" or otherwise—

that is at man this debate. but

rather the standard of evidence. the

testorcrlteriabywhichsuchevldence

is assessed and evaluted. . «

In this regard. it is instructive to

recall the Supreme Court's summary

dismissal of the argument of the dis-

sent by Justice Marshall in City of

representa-

D 0010

The compromise provision also pur-

ports to establish an explicit prohibi-

tion upon subsection (a) giving rise to

any right to proportional representa-

tion. This is not quite the case. Most

pointedly. perhaps. there is nothing in

the provision that addresses the issue

of proportional representation as a

remedy.

There is little doubt that many pro-

ponents of the results test, in fact. are

adamantly determined not to preclude

-9. - the use-of proportional representation

' as a basis for fashioning remedies for

violations of section 2."?

More fundamentally. however. the

purported “disclaimer" in

the amended section 2 is illusory for

other reasons as a protection against

proportional representation. It states:

“'nothlnginthissectionestsblishess

_,. i? right to have members of a protected clam

", . ., -..-._...-..m. elected in numbers equal to their proportion

i

1“} ‘v lnthe population.

It is illusory because the precise

. ,; "right" involved in the new section 2 is

:s 1;! not to proportional representation per

se but to political processes that are

"equally open to participation by

' ' members of a class of citizens protect-

' ed by subsection (a).” The problem. in

- _,, short. is that this right is one that can

be intelligently defined only in terms

that partake largely of proportional

representation. This specific right—po-

litical processes "equally open to par-

ticipation"—ls one violated where

there is a lack of proportional repre.

sentation plus the existence of what

" have been referred to as "objective

factors of discrimination." 1“

Such “objective factors” purport to

explain or illuminate the failure of mi-

norities to “fully participate" in the

political process. '

. They are described. in greater detail

7? . 'in the subcommittee report)" but the

,-‘j. ~ ~»- “most significant of these factors is

"-‘j " -7”! clearly the‘atdarge electoral aystmn.

The at-large system is viewed by some

in the civilrights community as an

:2 “objective factor of "

i ' - because they believe that it serves as a

i .4 “barrier" to minority electoral partici-

pation. , ‘7‘ ‘- ._ ‘ ,

7‘ Under the results test. the absence

of proportional representation plus

the existence of one or more “objec-

tiyegactors of discrimination.” such

. arr" at-large' system of governmen

_ wouldconstitute a section 2 violation.

M; _,In atechnical sense. it would not be

wafffn'and' or itself that would con-

Wilhénoiaubn but rather the

lick of proportional. representation in

combination. with the so-called chico-

>rfebarrfgrfitominority participation.

.- " ngbévw largely- irrelevant that

:- ere- was'no"

behind the at-large system, for exam—

ple, or that there were legitimate. non-

discriminatory reasons for its eshb-

._‘_ lishment or maintenance...- ._ ' , .

' .A We :2 as. "mm:

rs.” can in v oua,

; . eludes. ("some history ofdbu‘lminaflm‘.

iii (”15.9%. maximum: in mutt-mean.-

tory motive "

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE

districts?“ (3) some history of “dual” school

systems; “" (4) cancellation of resistration

for failure to vote: “- (5) residency require

ments for voters: "If (6) special requirements

for independent or third-party candidata;

"l ('1) off-year elections; “I. (8) substantial

candidate cost requirements: "I‘ (9) stag-

gered terms of office; I“ (10) high'wonomic

costs associated with registration; "n (11)

disparity in voter registration by race: 1"

(12) history of lack of proportional repre-

sentation; I“- (13) disparity in literacy rates

by race: I"- (14) evidence of racial bloc

voting; "'- (15) history of English-only bal-

lots; W (16) history of poll taxes: '9' (I?)

disparity in distribution of services by race:

W (13) numbered electoral posts; “" (19)

prohibitions on singleshot voting: “‘ and

(20) majority vote requirements. '-

Each of these factors. when they

exist within a governmental system

lacking proportional representation

may allegedly explain the lack of pro-

portional representation. In my view,

the results test leads inexorably to

proportional representation because it

is the absence of proportional repre-

sentation that triggers the search for

the “objective factors" of dimrimina.

tion in the first place. The theory of

the results test. again. is that such fac-

tors allegedly explain why such an ab-

sence of proportional representation

exists. Given the virtually unlimited

array of such “objective factors." it is

difficult to c any community.

with or without proportional represen-‘

tation, that would not be character-

ized by at least seVerai such factors.

Identifying an “objective factor of dis»

criminatlon" could easily amount to

little more than a mechanical and per~

functory process. In I“ practice. the re-

sults test. with or without the require-

ment that “objective factors of disp

elimination" be identified. is effective-

ly indistinguishable from a pure test

of proportional representation. w ~

The root problem with the amended

section“: then" that with" an inad-

equately strong—disdalmer sl

I mom

the present disclaimer b irrelevant

and misleading; the root problem is

with the results test itself. No. dis-

claimer, however strong—and the im-

mediate disclaimer is not very strong.

in any event. because of its failure to

address proportional reprwentation as

a remedy—can overcome the inexora-

ble and inevitable thrust of s results

test. indeed ofany testfor uncovering -

“discrimination" other than an intent '

tat "I .. .

If the comept discrimination is

going to be divor 7 entirely from the.

concept or' wrongful motivation-.then

we areno longer referring to what has

traditionally been viewed as discrimi-

nation: we are referring then simply to

the notion of-disparate impact. Dispa~

rate impact can, ultimately. be defined

only in terms that'ars effectively in?

distinguishable from those of pro-

portional representation.-

impact is not the equivalent of dis-

crimination. . ~ _ .

The attempt in the “compromise” to

define the results test as one focused

upon political processes that are not

“equally open to participation" is fine

‘ ”June .9, 1.982

rhetoric, but has been identified by

the Supreme Court in City of Mobile

for what it is at heart. The Court ob-

served in response to a similar descrip-

tion of the results test by Justice Mar-

shall in dissent:

The dissenting opinion would discard

fixed principles [of law] in favor of a Judi-

cial inventiveness that would so far toward

making this Court a “super-mature." l"

In short. the concept of a process

“equally open to participation" brings

to the fore what is perhaps the major

defect of the results test. To the

extent that it leads anywhere other

than to pure proportional represents

tion—and I do not believe that it

does—the test provides absolutely no

intelligible guidance to wurts in deter-

mining whether or not a section 2 vio-

lation has been established or to com-

munities in determining ”whether or

not their electoral structures and polio

cies are in conformity with the law.

What is an “equally open" political

process? How can it be identified in

terms other than statistical or results-

oriented analysis? Under what circum-

stances is an “objective factor of dis-

crimination." such as an at-large

system. a barrier to such an “open"

process and when is it not? What

:would a totally “open" political proc-

ess look like? How would a community

effectively overcome evidence that

their elected representative bodies

lacked proportional representation?

In my view. these questions can only

be answered in terms either of straight

proportional representative analysis or

in terms that totally substitute'for the

rule of law an arbitrary meby-case

srutlee of indievédlllilal Judges. As Justic:

vens no his comm-log op -

ioninCity ofMobile: ,, -; V

The results standard __ pondemn

‘every adverse impactononeormorepoliti-

cal groups without spawning more‘dilution

litigation than the Judiciary can manageJ"

On the opening day of heel-lugs. I

raised several factual situations with

my colleagues on the committee: relat-

ing to-Boston. Mass: Cincinnati. Ohio:

and Baltimore. Md. I asked repeatedly

how. given the circumstances in these

communities. would a mayor or coun-

yet to hear an ansz er

offering the slightest hit of- guid-

ance"! Each of. these munities

lacks “proportional.“ representation.

each has erected a conned bar-rim- to

minority participationln. the form of

an at-large council system. and each

possesses additional "objective factors

of Wot do ftion" such as sane hlsto '

ry_ acto‘ school-Inflation.

There'flftliéix‘é’afida'bf other commu-

nities across the Nation in dmilar cir-

cumstancesaswell. , 7 -

I reiterate my question: How does a

community. and how does aeourt.

know what it right and wrmg under

the results standard? How do they

know enough to. be able mreomply

with,the.law‘l:,How.-do they know

.._ ....... *‘_w._;m ‘ .r. . i ,. ._-,

3*

i2 3:. June 9,1982 COD

W .21. which laws and procedures are valid.

1e {and under what circumstances. and

b. E which are invalid? How do we avoid

D- ,. having “discrimination" boil down

r- ,2 either to an absence of proportional

ii representation or. in the words of one

rd :witness, “I may not be able to define

-

.—

'Iifi'fiyg;

it. but I know it when I see it”? 1"

There are other objections to the

‘ Emposed section 2 “compromise," but

;s. ...,_ arediscussedthoroughlyatan

:3 Zearlier point of my statement. I would

if ' note. however. that in one important

e respect the provision is even more 0!)-

er *Jectionable than the House provision.

L- git reters expressly to the "right” at

it tracial and selected ethnic groups to

o -’ “elect representatives at their choice."

-- This is little more than a euphemistic

)- reterence to the idea 01 a right in such

~ t‘"" . . . -- to the establishment ot sate

,. and secure political ghettoes so that

;-_ they can be assured of some measure

‘ . at proportional representation. In this

_ regard. I note the recent statement of

have anopportunity to elem candidate

at their choice. White people see nothim

nong withhavingaoapercentwhitedh-

\ié‘mtrict. Why can't we have 69 pa'eent black

ultimately is what this so-

ed right to “elect candidates ot‘

one ’5 choice" amounts to—the right to

ve established racially homogenoua

districts to insure proportion represen-

Te tation through the election of specific

., -umbers of black. Iiispanic. Indian.

utian. and Asian-American ot-

':3- ~ holdera‘"

Perhaps most importantly. the pro-

. 1"...» 3‘. “commune” suffers from the

2 =wmatthe Houseprovisioninthat

j attempts statutorily to overturn the

3'; preme Court’s decision in City of

"g .. phile interpreting the 15th amend-

iii: ut. It is altogether as unconstitu-

g on mal, in my view. as the unamended

. ““1

, -

i

:w-Wmemmm~m . ,_ .

"my,

'1 -use language. “3 Under our system

* of, government the Congrem simply

cannot overturn a constitutional deci-

tion of the Supreme Court through a

_4 statute. The Court has held that

Mn *‘ f__ 15th amendment requires a dem-

m , . _.... - .otmtentionaiorpm-puetnt

. u .. "amnion. To the extent that the

, .' ...- Rights Act generally and seed,

:1? ~' .1 L2- aspecitieallyarepredieatedupoq

em. ,. l, ‘ amendmeand they mm

4; . ; , authoritywithinConsI-efltore-

~-—— * .3 ~ m - ~ its requiremenu~ and’W

« .... . steater._"restrictionsuponthe‘

E;

E

:3.

a

E?

W

3

'5

'.,‘i.

“x

_ ‘I'here‘isnopowerwithindon‘

53:: the Court, a least so long a the

. era! Government remains a govc

hunt nf delmted powers. '7

arm.” 2-.“ ”'7 - "w “

the proposed change in section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act would lead to

widespread court-ordered "proportion-

al representation." Put simply. propor-

tional representation refers to a plan

of government which adopts the racial

or ethnic group as the primary unit of

political representation and appor-

tions seats in electoral bodim accord-

ing to the comparative numerical

strength of these groupa‘" The con-

cept of proportional representation

has been experimented with—often ac-

companied by substantial social divi-

sion and t 'oil—in a handful of na-

tions aroun the world)“ There

seems to be. general agreement that

the framers of our Federal Govern-

ment rejected official recognition of

interest groups as a basis for represen-

tation and instead chose the individual

as the primary unit of government)”

I am deeply concerned with this issue

since the proposed change in section 2

could have the consequence of bring-

ing about a substantial change in the

fundamental organization of American

political society. .

1. smears m 230”“?!on

The analysis of this issue begins

with the language of. the proposed

change in section 2. Existing section 2

provides that: ‘

No voting qualification or prerequisitive

to voting. or standard. practice. or proce-

dure shall be imposed or applied by any

State or political subdivision to deny or

abridge the right of any citizen of the

United States to vote on amount of race or

color or in contravention of the guarantees

set forth in section 4(fx2).“'

The Senate amendment eliminates

the words “to deny or abridge” and sub-

stitutes the words “in manner which re

sults in a denial or abridgement of.” The

Baum committee report explains that:-

ER. 8112 will amendeseetion 2 of the act

to make clear that proof of disalminatory

purposeorintentisnotrequiredmcasel

brought under the provision)“

Under the current language, as con-

strued by the Supreme Court in the

Mobile case. a violation of section 2 re-

quires proof oi‘ discriminatory purpose

or intent. The Senate bill changes the

gravamen of the claim to proof of a

disparateelectoralresult'l'his ..

inthe very essence of them

of courts upOn

:anadequato remedy merely by declar-

ing the purposefully

action- void. since the essence of the;

motivated official

action— However? under the proposed—

change in section 2,- the right estab-

lishedistosparticularresultandso.

inevitably. much more will be required

to provide an adequacy remedy. The

obligations of Judges will require use

of their equity powers to structure

electoral systems to provide a result

that will be responsive to the new

right."' Otherwise. the new right

would be without an effective remedy.

I. nose-trons summon n no: ’

Perhaps the most important and dis-

m issue brought to light

the bearingswas the issueof whether

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE

June 9,1982

a state of affairs which is logically and

legally unacceptable.

Thus launched in search of a remedy

involving results. it seems that courts

would have to solve the problem of

measuring that remedy by distribu.

tional concepts of equity which are in.

distinguishable from the concept of

proportionality. The numerical contri~

bution of the group to the age-elegible

voter group will almost certainly dic-

tate an entitlement to office in similar

proportion)" It is my opinion that if

the substantive nature of a section 2

claim is changed to proof of a particu.

lar electoral result. the principles of

equity will lead to widespread estab-

t1lishment of proportional representa-

on.

Virtually the same conclusion was

stated by humus witnesses who ap-

peared before the Subcommittee on

the Constitution. Attorney General

Smith told the subcommittee:

[Under the new test] any voting law or

procedure in the country which produces

election results that fail to mirror the popu-

lation's makeup in a particular community

would be vulnerable to legal challenge ‘ ‘ '

it carried to its logical conclusion. propor-

tional representation or quotas would be the

end result.‘“

Assistant Attorney General Reyna

olds testified:

A very real prospect is that this amend-

ment could well lead on to the use of quotes

in the electoral process ' ° ° we are deeply

concerned that this language will be con-

strued to require governmental units to

present compelling Justification for any

voting system which does not lead to pro-

portional representationl "

Professor Horowitz testified that

under the results test:

*Whatthecouriaaregohlgtohavewdois

to look at the proportion of minority voters

lnagivenloalityandlookatthepropor-

tion of minority representatives in a given

locality. That is where they will begin their

inquiry; that is very likely where they will

end their inquiry. and when they do that.

lwe will have ethnic or racial proportional-

ty ll

Professor Bishop has written the

subcommittee: -

it seems to me that the intent of the

amendment is to insure that blacks or mem-

beu of other minority mare insured}

W 'forwesm-

WW

pie. blacks are 20 percent of the population

ofamnhpmiulupercentandfndians

apercentthenatleastmiaercentofthe

mull: A- 1~-'..1. ".y.'v ' ." 5.4791-

Professor Abraham has stated?”

Only those who live in a dream

falltoperceivethebasiepurpoeeand -

and inevitable result of the new sectian 2. It

is to establisha patternot proportionate}

resentation. now based upon race—but who

btosay. sifl—perhapsatalatermomentin

time upon gender. or religion. or national—

ity. or even aged “

A similar conclusion—that the con-

cept of proportional representation of

race is the inevitable result of the

in section 2—was reached by I

large number of additional witnesses

and observers.“m ‘

1

x

; :3.