Boards and Commissions Highlights 1981- Present

Working File

July 5, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Thornburg v. Gingles Working Files - Guinier. Boards and Commissions Highlights 1981- Present, 1983. 027c9912-df92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b2a38eab-7479-4182-ba34-df1854933d24/boards-and-commissions-highlights-1981-present. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

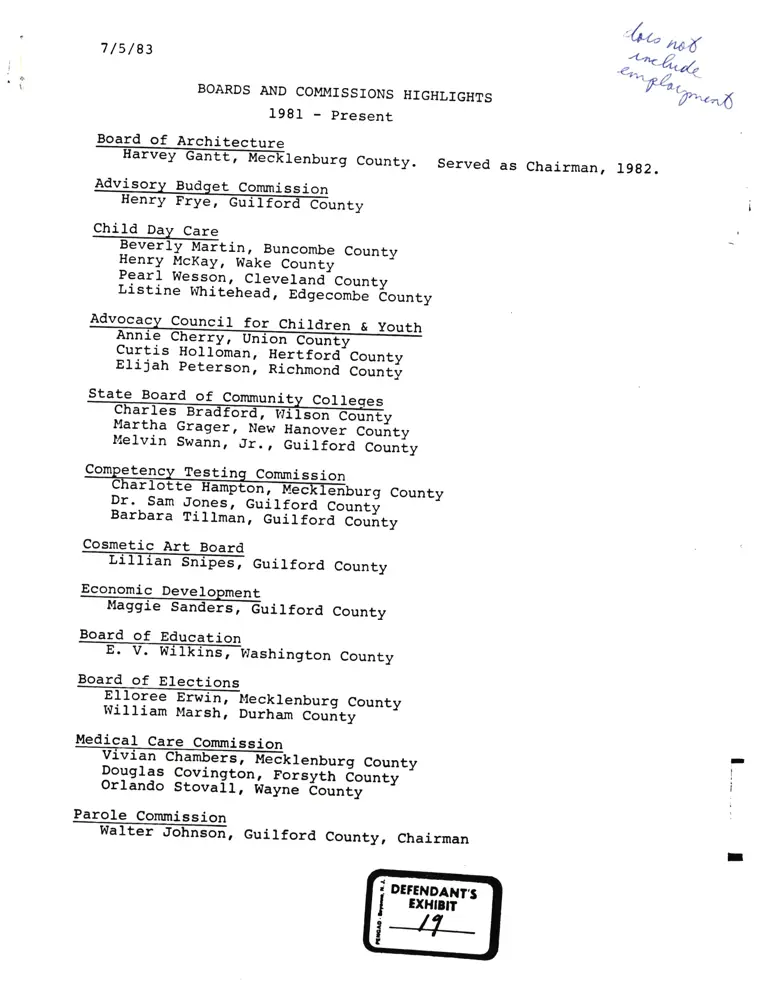

7/5/83 (it”‘téfwé

"“Mu-

BOARDS AND COMMISSIONS HIGHLIGHTS flhV”V6

1981 - Present

Board of Architecture

Harvey Gantt, Mecklenburg County. Served as Chairman, 1982.

Advisory Budget Commission

Henry Frye, Guilford County

Child Da Care

Beverly Martin, Buncombe County

Henry McKay, Wake County

Pearl Wesson, Cleveland County

Listine Whitehead, Edgecombe County

Advocacy Council for Children & Youth

Annie Cherry, Union County

Curtis Holloman, Hertford County

Elijah Peterson, Richmond County

State Board of Community Colleges

Charles Bradford, Wilson County

Martha Grager, New Hanover County

Melvin Swann, Jr., Guilford County

Competency Testing Commission

Charlotte Hampton, Mecklenburg County

Dr. Sam Jones, Guilford County

Barbara Tillman, Guilford County

Cosmetic Art Board

Lillian Snipes, Guilford County

Economic Development

Maggie Sanders, Guilford County

Board of Education

E. V. Wilkins, Washington County

Board of Elections

Elloree Erwin, Mecklenburg County

William Marsh, Durham County

Medical Care Commission

Vivian Chambers, Mecklenburg County

Douglas Covington, Forsyth County

Orlando Stovall, Wayne County

Parole Commission

Walter Johnson, Guilford County, Chairman

4

I"

DEFENDANT!

I mum

g~L

7/5/83

Page 2

Boards and Commissions Highlights, 1981 - Present

Ports Authority

William Clement, Durham County

State Goals and Policy Board

Carolyn Coleman, Guilford County

Jim Mebane, Guilford County

Council on Status of Women

Ruby Jones, Guilford County, Chairperson

State Health Coordinating Council

Marion Boyd, Mecklenburg county

Howard Fitts, Durham County

Treva Oglesby, Buncombe County

Henry Pitchford, Warren County

George Walker, Wake County