Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 4, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1983. b41fc692-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/b35a5683-b113-430e-bc1a-4f59b8890171/clark-v-little-rock-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

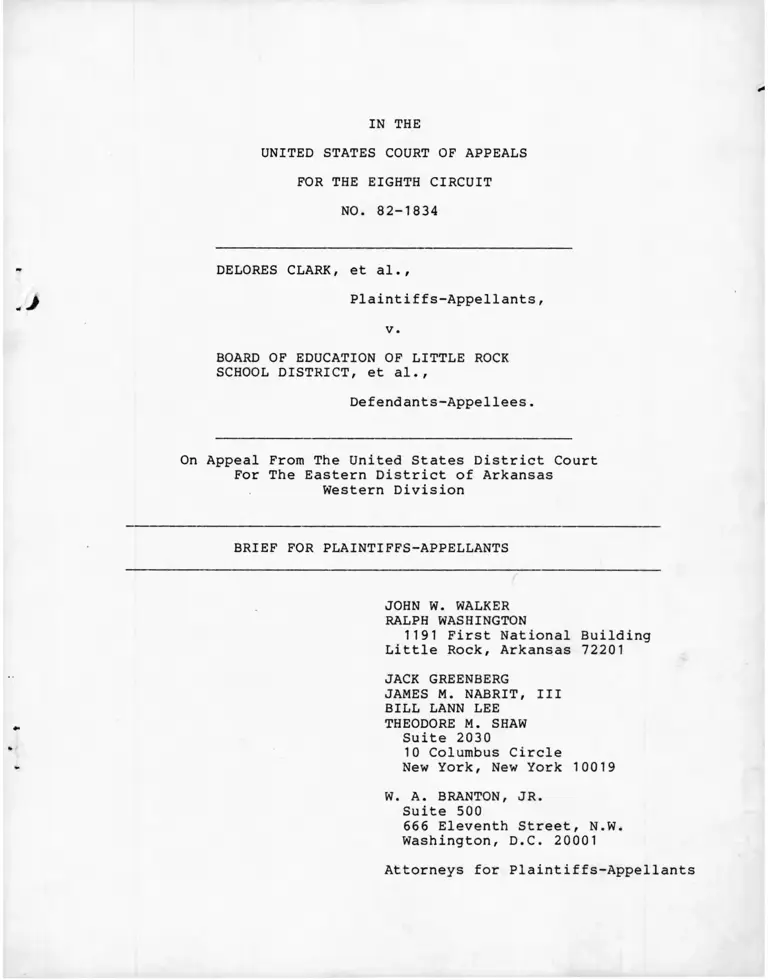

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-1834

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF LITTLE ROCK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas

Western Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JOHN W. WALKER

RALPH WASHINGTON

1191 First National Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE

THEODORE M. SHAW

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W. A. BRANTON, JR.

Suite 500

666 Eleventh Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

4

SUMMARY AND REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

This is a school desegregation case which was

originally filed more than a quarter century ago to

disestablish the dual system of public education in the

public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas. A potentially

meaningful desgregation plan was not entered in this case

until 1973. However, the School Board engaged in a series

of segregative actions in the areas of student classroom

assignment, faculty assignment and school abandonment and

construction. The immediate proceedings below concern the

approval by the District Court of a segregative student

assignment plan in which black elementary students

were assigned to four virtually all black schools. The

District Court also failed to alleviate student classroom

assignment, faculty assignment and school abandonment and

construction problems. It is respectfully suggested that

oral argument is required in light of the issues presented

in this lengthy litigation and generally. The issues

presented are significant because they concern the extent

of a school district's affirmative obligation to desegre

gate. At least 15 minutes of oral argument would be

appropriate.

i

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................ 1

STATEMENT ...................................... 2

1. Prior Proceedings .................. 2

2. Post-1972 Proceedings .............. 10

3. Proceedings Below .................. 15

ARGUMENT ....................................... 20

I. The Duty of Defendant School Board

and the District Court Was "'To

Come Forward With A Plan That

Promises Realistically To Work ...

Now ... Until It Is Clear That

State-Imposed Segregation Has Been

Completely Removed'"................ 2 3

II. The District Court Wrongly Approved

Partial K-6, Which Unconstitutionally

Resegregates Substantial Numbers of

Black School Children and Failed to

Correct Student Assignment, Faculty

Assignment, and School Closing and

Construction Problems .............. 26

CONCLUSION .................................... 32

l

TABLE OF CASES

Cases Pa9e

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 885 (E.D. Ark.

1956) ........................................ 2

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957).... 2

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958), aff'd,

358 U.S. 1................................... 3

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) .... 3

Aaron v. McKinley, D.C., 1973 F. Supp. 944 (3

judge court), sub. nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361

U.S. 197 ..................................... 3

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396

U.S. 19 (1969) .............................. 5

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Corpora

tion, 429 U.S. 252 (1977) .................... 29

Clark v. Board of Directors of Little Rock School

District, 328 F. Supp. 1205 (E.D. Ark.

1971)......................................... 6,7

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

District, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966 ..... 4,5

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

District, 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970) .... 4,6

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449 (1979) .................................. 22,2 3,24,25,2 6,2 8,29,31

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ................ 2,21

Davis v. School Comm'rs of Mobile County, 402

U.S. 33 (1971) .............................. 23, 24

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526 (1979)................................... 24,25,26,27

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 ....... ........... 3

Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir.

1958), cert. denied 358 U.s. 829 ............ 3

- ii -

1

Cases Page

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430,

(1968) .......................................... 2,5,9,23,2 4

Higgins v. Board of Education, 508 F.2d 779 (6th

Cir. 1974) ..................................... 29

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education,

687 F . 2d 814 (6th Cir. 1982) .................. 2 7,2 8

Martin v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

475 F. Supp. 1318 (W.D.N.C. 1979), aff'd on

other grounds, 1165 (4th Cir. 1980), cert.

denied, 450 U.S. 1041 ( 1981 ) .................. 22

McNeal v. Tate, 508 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1975) ..... 30

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) .......... 26,2 7,29

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 ( 1977) ........... 31

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968) ........................................... 5,29

Monroe v. Board of Education of Chidester School

District No. 59, 448 F.2d 709 (8th Cir.

1971) ........................................... 8

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir.

1961) ........................................... 4

Parham v. Dove, 371 F.2d 132 (8th Cir.

1959) ........................................... 3

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 ( 1976) ................................ 2 6, 2 7

Raney v. Board of Education of Gould School

District, 391 U.S. 443 ( 1968) ................. 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 ( 1971) .............................. 2 3, 2 4, 25,2 6,

2 7, 2 8, 31

Thomason v. Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir.

1958) ........................................... 3

United States v. Board of Commissioners of

Indianapolis, Indiana, 503 F.2d 68 (7th Cir.

1974) ........................................... 2 9

- iii -

Cases Page

United States v. Gadsden City School District, 572

F .2d 1045 (5th Cir. 1978) ...................

United States v. Scotland Neck Board of Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) ..........................

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ...................................

'30

2 4,25,29

24

IV

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The Honorable William Ray Overton rendered the decision

from which plaintiffs hereby appeal. Jurisdiction of the

district court was invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1343,

1331. This court's jurisdiction is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1292(b). The Memorandum and Order were filed on

July 9, 1982, and timely notice of appeal was filed on July

9, 1982.

STATEMENT OF ISSUE

Whether the District Court erred by allowing the Little

Rock School District, which is under a constitutionally

imposed duty to dismantle the remaining vestiges of a formally

dual system of public education,

(a) to attempt to retain or regain white students

by resegregating black students in four virtually all black

schools; and

(b) to fail to correct segregatory and discriminatory

student classroom assignment, faculty assignment and school

closing and construction policies. Columbus Board of Education

v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459-63 (1979); Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971).

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 82-1834

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF LITTLE ROCK

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Eastern District of Arkansas

Western Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the District Court erred by allowing the

Little Rock School District, which is under a constitution

ally imposed duty to dismantle the remaining vestiges of a

formerly dual system of public education,

(a) to attempt to retain or regain white students

by resegregating black students in four virtually all black

schools; and

(b) to fail to correct segregatory and discrimina

tory student classroom assignment, faculty assignment and

school closing and construction policies.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This appeal once again brings to this Court one of

the oldest and most famous school desegregation cases for

determination of issues relating to the duty of a former

racially dual system of schools to "take whatever steps

might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in

which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and

branch." Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430,

437-38 (1968). Specifically, plaintiffs appeal from

a district court order which allows the School District

to establish four segregated schools with all black

enrollments and which ignores the continuing vestiges of

racial discrimination which still permeate the Little

Rock public schools.

1. Prior Procedures

This litigation began in 1956 when plaintiffs filed

a class action seeking desegregation of the public

schools of Little Rock. Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp.

885 (E.D. Ark. 1956). On appeal in 1957, this Court

approved a plan for gradual desegregation by 1963 which

was based upon geographical attendance zones. Aaron v.

Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957). The District Court

was ordered to retain jurisdiction to supervise transition

to a nondiscriminatory system. It was the attempted

implementation of this plan that led to the Supreme

Court's famous decision in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1

2

(1958). In the process various state officials were

enjoined from impeding the mandate to desegregate,

resulting in this Court's decisions in Thomason v.

Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958) and Faubus v. United

States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358

U.S. 829. In Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir.

1958), aff'd. 358 U.S. 1, this Court denied an attempt by

the School Board to impose a two and one-half year

moratorium on desegregation. In 1958 the Arkansas

legislature enacted legislation which closed the Little

Rock public schools for the 1958-59 school year. The closing

was held to be unconstitutional in Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F.

Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark. 1959) (3 judge court), aff'd sub, nom.

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197.

Undaunted in its efforts to evade its constitu

tionally imposed duty to dismantle the prior dual system

of schools, the Board next attempted to lease the public

school facilities to a private school system which would

continue to operate the segregated schools. This Court

struck down that scheme in Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97

(8th Cir. 1958).

Next, during the 1959-60 school year the Board

assigned students to school on the basis of a state

student assignment law, which, although this Court found

was not facially unconstitutional in Parham v. Dove, 371

F.2d 132 (8th Cir. 1959), was subsequently found to be

3

unconstitutional as applied. The School District was

once more ordered to effect a transition to a non-dis-

criminatory system. Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798, 809

(8th Cir. 1961).

The School District responded by adopting a freedom

of choice plan for 1964 for grades one, four, seven and

ten, which resulted in only token desegregation at some

all-white schools. Clark v. Board of Education of Little

Rock School District, 369 F.2d 661, 664 (8th Cir. 1966).

This Court generally upheld the plan but remanded the

case to the District Court with orders to oversee the

correction of certain deficiencies. Specifically,

the Court found that the plan did not provide adequate

notice for annual choice of schools and that it did not

adequately provide a definite plan for faculty and staff

desegregation. Clark v. Board of Education of Little

Rock School District, 369 F.2d 661, 671 (1966).!/

]_/ Between 1967 and 1968 two plans for desegregation

were submitted to the School Board. The "Oregon Report",

submitted in 1967 by a team of experts from the University

of Oregon, called for "abandonment of the neighborhood

school concept and the development of an educational park

system though the institution of a capital building

program and the pairing of schools." Clark v. Board of

Education of Little Rock School District, 426 F.2d 1035,

1037-38 (8th Cir. 1970) (footnote omitted). The proposal

was abandoned by the Board after the 1967 School Board

election, in which an incumbent supporter of the "Oregon

Report" was defeated by an opponent of the plan.

[footnote continued]

4

After further proceedings in the District Court

initiated by plaintiffs' motion for further relief filed

on June 25, 1968, the District Court approved, with some

amendments, the Board's plan for pupil assignment based

on geographic attendance zones. Clark, id., at 1039-40.

The amendments ordered by the Court included, inter alia,

pairing of certain neighborhood schools. Both parties

appealed. Plaintiffs argued that geographical zones

served to perpetuate segregated schools and that the plan

did not adequately desegregate faculty. The Board argued

that the Constitution did not require transportation to

particular schools and did not allow assignments according

to race. This Court, citing Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Raney v. Board of Education

of Gould School District, 391 U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v .

Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968); and Alexander

v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969),

approved the Board's faculty desegregation plan but found

the student assignment plan to be constitutionally

deficient.

j[/ (continued)

Subsequently the School Board considered the "Parsons

Plan", named for the Superintendent of Schools under whom

the plan was developed. Under the "Parsons Plan" the high

schools would be paired. Horace Mann, a black high school,

would be closed. No provision was made for desegregating

junior high schools. A bond issue required to finance

implementation of the "Parsons Plan" was defeated in March

1968, and thus, during the 1968-69 school year students were

still assigned to schools according to "freedom of choice."

Clark, Id., at 1038.

5

In striking down the Board's student assignment plan

this Court said

In certain instances geographic zoning may

be a satisfactory means of desegregation. In

others it alone may be deficient. Always,

however, it must be implemented so as to

promote desegregation rather than to reinforce

segregation....

When viewed in the context of the above

principles, the plan approved by the district

court is constitutionally infirm. For a

substantial number of Negro children in the

District, the assignment method merely serves

to perpetuate the attendance patterns which

existed under state mandated segregation, the

pupil assignment statute, and "freedom of

choice" — all of which were declared uncon

stitutional as applied to the District. In

short the geographical zones as drawn tend to

perpetuate rather than eliminate segregation.

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School District,

426 F.2d 1035, 1043 (1970).

The Court rejected the School Board's appeal and

remanded the case to the District Court with directions

that required the Board to submit a constitutionally

effective plan which would be fully implemented "no later

than the beginning of the 1970-71 school year." Id. at

1 046.

Once again the District Court attempted to devise a

plan which would pass constitutional muster. Clark v.

Board of Directors of Little Rock School District, 328 F.

Supp. 1205 (E.D. Ark. 1971). The District Court rejected

a School Board proposal that would have reorganized the

district on a 5-3-2-2 basis. Under the plan, both

graduating high schools would have been in predominantly

6

white eastern Little Rock, and one middle school complex,

Gibbs-Dunbar, would have had a black enrollment of over

90 percent. I<3. at 1213.

Instead, the Court approved a plan which utilized

pairing, clustering, and contiguous and noncontiguous

zoning as desegregative techniques. Under the Court-

approved plan,

grades 6 through 12 would be integrated at the

beginning of the 1971-72 school year. All

students in grades 6 and 7 would be assigned to

four middle school centers located in the

generally white residential areas in the

western sections of the city; all students in

grades 8 and 9 would be assigned to four junior

high school centers, three of which are in the

largely black residential areas in the eastern

section of the city; and all students in grades

10 through 12 would be assigned to three high

school centers, two in white residential

areas and one-Central High School-in central

Little Rock.

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, 449 F.2d

493, 495 (1971).

Desegregation of elementary schools was to be

delayed for one year, until the 1972-73 school year. At

that time, however, the School Board was to disestablish

racially identifiable schools "by means of pairing and

grouping schools and assigning students to them so as to

destroy their former racial identifiability." Clark v.

Board of Directors of Little Rock School District, supra

328 F. Supp. at 1219.

Again, both parties appealed. The Board claimed

that its plan which would have left the Gibbs-Dunbar

7

Complex 95% black, was constitutionally permissible, that

desegregation of elementary grades should not be required

in 1972-73, and that the Board should not be required to

provide certain transportation.

This Court approved the Board's plan with respect to

secondary schools, but required the School Board to

immediately establish objective nondiscriminatory teacher

reassignment criteria consonant with standards set forth

in Moore v. Board of Education of Chidester School

District No. 59, 448 F.2d 709 (8th Cir. 1971). With

respect to elementary schools, this Court took note of

the long history of segregated schools and the inordinate

delay on the part of the School Board in desegregating

those schools. The Court required the Board to adopt a

time-table and to immediately begin progress toward

implementation in 1972-73 of a plan that would utilize

pairing, clustering, contiguous and non-contiguous

zoning, and the use of student transportation to effec

tuate transition to a unitary system. Clark, supra 449

F.2d 493 at 498-499.

Once again the District Court approved a plan from

which plaintiffs appealed; once again this Court was

unable to approve the plan in its entirety. The Court

was able to approve the portion of the elementary school

plan that called for zoning, pairing and clustering in

grades 4 and 5. Under the plan, fourth grade students

8

from eastern and western Little Rock would attend schools

in predominantly white western Little Rock. Fifth grade

students from those areas were assigned to schools in

predominantly black eastern Little Rock. The Court also

approved the provision in the plan for neighborhoood

schools in central Little Rock "insofar as it provides

for the integration of grades 1 through 5 in the central

section of the city ... because this aspect of the plan

preserves the neighborhood school in relatively integrated

neighborhoods, and there is nothing to suggest that

students in these grades will not be placed in fully

desegregated classrooms and school buildings." Clark v .

Board of Education of Little Rock, Arkansas, 464 F.2d

1044, 1046 (1972). (Emphasis added and footnote omitted).

This Court, however, could not approve that portion

of the plan which purported to desegregate grades 1-3 in

the eastern and western section of the School District by

assigning those students to their neighborhood schools.

Id., 1047. Dismissing the School Board's argument that

the plan was sufficient because students in grades 1

through 3 will be attending schools with desegregated 4th

and 5th grades, the Court observed that "it appear[ed] to

be a last ditch effort to retain a segregated school

system in the primary grades contrary to the Surpeme

Court's mandate that segregation be eliminated 'root and

branch.'" Id., 1047 (citing Green v . County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430, 437-38 (1968)).

9

The Court remanded and ordered that the School Board

develop a plan for grades 1-3 in eastern Little Rock

similar to that adopted for grades 4 and 5. Implementa

tion was scheduled for the beginning of the 1973-74

school year.2./ Id.

2. Post-1972 Proceedings

Pursuant to a court-approved stipulation between the

parties a plan was implemented during the 1973-74 school term

(Tr. 250-51) that remained in effect, with some modifications

until the implementation of the plan which is the subject of

this appeal. The stipulation entered on June 23, 1973,

reflected the terms of a moratorium agreement whereby litiga

tion by plaintiffs would be foregone or held in abeyence in

order to allow the School Board time to develop and implement

desegregation in an atmosphere free of litigation. As part

of the 1973 moratorium plaintiffs made a concession that al

lowed all lower elementary grades to be placed in white neigh

borhoods. Tr. 270. In turn, the Board agreed to keep the

2/ The Court also voided a modification of the Board's

plan by the District Court which would have required

assignment of faculty in a manner so that elementary

schools with a greater number of students of one race

would have a greater number of faculty of the other race.

Instead, the Court thought it sufficient that teachers be

assigned to schools in substantially the same proportions

that they are found throughout the system. Clark v.

Board of Education of Little Rock, Arkansas, 464 F.2d

1044, 1048 (1972). The Court also agreed sufficient

objective criteria for faculty reassignment did not exist

but remanded the issue to the District Court for develop

ment of an adequate record. Id., 1049.

10

the schools as racially balanced as possible. Tr. 33-34.

In particular, the Board was required to stay within a 10%

deviation of the average racial percentage on each particular

level. Tr. 39, 98.

After 1973 various modifications to the existing

plan were presented to either the Biracial Committee or

to the plaintiffs for consideration and discussion. In

the spirit of the moratorium, the plaintiffs did not inter

pose formal objections until 1979 when it became clear to

plaintiffs that their objections to the manner of implemen

tation of desegregation were not being heeded. Tr. 257.

During the period in which the moratorium agreement

remained in effect, the District engaged in a series of

segregatory and discriminatory acts, including student

assignment, faculty assignment and school construction

policies and practices. With respect to student assign

ment, Board Member Betty Herron admitted that the Board

engaged in "tracking" of students within ostensibly

desegregated schools. Tr. 217. (See also testimony of Dr.

Patterson, Tr. 321). On the intermediate level, students were

assigned to classes through ability grouping on the basis of

test performance and teacher recommendations. _Id. Black

students generally scored lower on standardized tests. Tr.

62. The result of testing and teacher recommendations was

racially identifiable classes on the intermediary level.

Tr. 216. Although the District does not currently administer

I.Q. tests (Tr. 128) it her used them for some assignment

purposes. Generally it is true that if I.Q. tests are used

for purposes of classroom assignments segregated classes will

result. Tr. 118.

On the secondary level, there are basic, regular,

enriched and honors classes (four levels). Tr. 215. Student

placement resembled a bell curve, with 20% of the students at

either end and 60% in the middle. On either end the students

were of one race, i.e. honors classes were predominantly white

and basic classes are predominantly black. Tr. 402. In the

middle, regular courses were largely black. Tr. 409-410.

Since 1973, only 5% of all honors graduates have been black.

Tr. 366. At the time of trial, of 76 students in three high

schools (Parkview, Hall and Central) taking physics, only one

was black. Tr. 404. At Parkview there were no blacks in

3/advanced biology. Tr. 404.

Testimony at trial also indicated that special

education classes were racially segregated. Specifically,

classes for the learning disabled have been virtually all

3/ Moreover, some honors classes have as little as 8-10

students; no special education class has as few. Tr. 116, 117.

12

black while the related educable mentally retarded clsses

were virtually all white. Tr. 112. Moreover, in 1976

federal funds were temporarily withheld because over 1,000

black children were discriminatorily relegated to special

education classes. Tr. 322.

The School Board offered no evidence that its

program of extensive classroom segregation was justified

by any legitimate educational benefit to students.

Black faculty have not, for the most part, advanced

to upper level i. e . , supervisory positions. Not one high

school principal is black. Tr. 110. Although there are

approximately 15 instructional supervisors, no black

supervises, or has ever supervised, academic instruction,

with the exception of special education, on the secondary

level. Tr. 11, 350. For example, in 1980, Dr. Ruth

Patterson, supervisor for human relations for the School

District, was recommended by Paul Masem, then superintend

ent of the Little Rock public schools, for the position of

Supervisor of English and Social Studies. Tr. 327. In Mr.

Masem's opinion, Dr. Patterson was eminently qualified for

the job. Tr. 447. Nevertheless, Masem was instructed by the

Board to remove Dr. Patterson's name from the list of candi

dates and the position was given to a white male with lesser

qualifications. Tr. 327. Dr. Herbert B. Williams, assoc

13

iate superintendent of educational programs, testified that

in his opinion Dr. Patterson was qualified for the position

of Supervisor of English and Social Studies and knew of no

valid reason why she was not given the position. Tr. 415.

Moreover, although Mr. Williams, who is black, is second in

the school district's hierarchial structure, when Superintend

ent Masem was placed on inactive status by the School Board,

Mr. Williams was by-passed in favor of a white woman, who was

made acting superintendent. Tr. 129-130.

During the moratorium years, the District engaged

in school closing and construction policies which were

segregatory and imposed the burden of desegregation

disporportionately on black students. Thus, schools in

black neighborhoods have been disproportionately closed

without justification. Tr. 55, 104, 210. School

construction proceeded in white neighborhoods at a time

when capacity existed at schools located in the black

community. Tr. 108. Schools built in western Little Rock

during the last 2 1/2 years have not been filled as pro

jected. Tr. 57.

On May 4, 1979, plaintiffs moved for further relief.

The District court, however, has never remedied the

Board's student assignment, faculty, and school closing

and construction practices.

14

Subsequently, on August 27, 1981 the Board passed a

resolution which provided that during the 1981-82 school

year homerooms in grades 1-3 of the primary schools

"be integrated, as far as possible, in accordance with

the approximately 65 to 35 race ratio in the overall

Little Rock School District and that, as far as possible,

in no case in these schools should a minority be repre

sented by less than 35% of the total enrollment in a

homeroom class if that minority is represented at all."

See "Stipulation," App. 1. The School District stipulated

that "[i]n the event the Board's Resolution is implemented

some of the primary classes within the Little Rock School

District will be all black; in the event the proposal is not

implemented, all of the primary classes will have a mixture

of black and white students." App. 1. The plan, known as

the "65-35 plan," was opposed by plaintiffs and rejected by

the District Court after a hearing in September, 1981 which

led the Court to conclude that it was "not a constitutionally

permissible plan of student assignment." Order of District

Court of 9/3/81.

3. Proceedings Below

On April 26, 1982, the Little Rock School Board

adopted a plan by which it knowingly created four segre-

15

gated schools with all black enrollments.- Tr. 168.

The plan, known as "Partial K-6", was offered as an attempt

to entice white parents to keep their children in the dis

trict and to regain some who had left. Tr. 304. "Partial

K-6" included restructuring of attendance zones to facilitate

reestablishment of neighborhood schools. Tr. 122. Because

Little Rock's residential patterns are racially segregated,

neighborhood schools are inevitably segregated schools.

Tr. 175.

The underlying thesis of "Partial K-6" is that

the School District will be able to retain white children

and perhaps even regain some who have left if it provides

an opportunity for them to attend some schools at which the

black population is relatively low because black students

are concentrated elsewhere. Tr. 444. Stated differently,

if the School Board segregates some black students in order

to increase white percentages in certain schools, some white

children will be attracted back to the system. Tr. 90.

Indeed, as one School Board member explained, the concept

behind "Partial K-6" is "to provide an integrated school

system in the elementary grades for as far as our white

children will go." Tr. 276. (Emphasis added.)

4/

4/ Under "Partial K-6" four schools, Rightsell, Mitchell,

Ish and Carver, would have over 90% black enrollment.

Rightsell would be 96% black, Mitchell 99%, Ish 99%, and

Carver 99%. The number of nonwhite students (1,484) in

these schools would represent approximately 13% of all

students in the elementary schools and approximately 19%

of the non-white students in elementary schools. L.R.S.D.

Reorganization Impact on Students, Instructional Programs,

Personnel, Resources, Logistics, Physical Plants - Paul

Masem, Superintendent (April 5, 1982)

16

The Board voted to implement "Partial K-6" in spite

of the fact that it not only established four segregated

schools, it also resulted in overcrowding at those

schools.—/ And the Board voted to implement the plan

in spite of the fact that, as Dr. Paul Masem (who at the

time the Board approved "Partial K-6" was the superinten

dent of the Little Rock School District) testified, the

educational impact of "Partial K-6" on students in the

four segregated schools would be a rather significant

gap in performance between them and their white counter

parts. Tr. 440. Dr. Masem testified that overcrowding

4/ For example, during the 1981-82 school term Carver

enrolled 309 students (263 excluding kindergarten); under

"Partial K-6" enrollment was projected to be 504 (453

excluding kindergarten). Carver's capacity is 450. In

1981-82 Carver's student enrollment was 59% black. Given

the racial composition of the school district, it was

well integrated. Tr. 165. Under Partial K-6,

that will change. White children who attended Carver

last year from the Williams school area will now attend

Brady and Jefferson, both of which are located in white

neighborhoods. Tr. 165.

Of course, the creation of four all-black segregated

schools has the corresponding effect of making other

schools disproportionately white. Tr. 172-73.

For example, in 1981-82 at Brady there were 52 white and

21 black children in kindergarten. Under "Partial K-6"

there will be 34 white children and one black. Tr. 190.

At Meadowcliff, in 1981-82 there were 29 white and

20 black kindergarten children. Under "Partial K-6" there

will be 0 blacks in kindergarten.

And the Wilson school, which was

will be 44% white. Tr. 173.

21% white in 1981-82

would have detrimental effects because higher performance

among black students currently seems to benefit from lower

student teacher ratios. The four segregated schools, partic

ularly to the extent that they are overcrowded, would be "at

a real disadvantage to provide quality education." Tr.

440-41.

The plan also contemplated a magnet school which was

located at the Williams school in a virtually all-white

neighborhood. Tr. 203. The magnet was located pursuant to a

School Board stipulation that it would have to be west of

University Boulevard, which is perceived to be the boundary \

between black Little Rock and white Little Rock. Tr. 204.

Western Little Rock is predominantly white.

The magnet is a K-6 school which operates a random

selection procedure based on attendance zones. Its

projected enrollment was 500 students. Its planned

racial composition was 50% black, 50% white, with a 10%

allowable variance. Tr. 199. In effect, the magnet compo

nent of "Partial K-6" establishes a disproportionately white

"ideal school" in the predominantly white western section of

Little Rock while four overcrowded segregated schools are

established in predominantly black eastern Little Rock. Tr.

5/340.~

5 / Thedford Collins, a black member of the Patrons'

Committee who opposed "Partial K-6" (Tr. 224-25)

testified that the proposed magnet at Williams is

18

An additional result of "Partial K-6" is an increase

in the burden of transportation on black students. Under

the reorganization students would be reassigned from

Booker Junior High School. As a result, at the junior

high school level, it was projected that approximately

312 black students would be transported by bus who had

not been previously transported. Tr. 58-59. Under the plan,

no additional white children would be bussed. Tr. 226-27.

The School Board petitioned the District Court for

approval of "Partial K-6" and a hearing followed on June

7 and 8, 1982. On July 9, 1982, the District Court ruled

that ” [u]nder the circumstances of this case, Partial K-6

Plan is a constitutionally sound plan which may be imple

mented by the Little Rock School District." Memorandum

and Order of July 9, 1982, at 18. The Court based its

ruling, in part, upon the conclusion that "[a]s a tool

for accomplishing desegregation of elementary grades, the

present plan has, perhaps, outlived its usefulness. The

5 / (continued)

not truly a magnet, since it does not offer a special

curriculum. Rather, it offers a basic program that is

available elsewhere in the district. Tr. 304.

The Patron's Committee was established by the Board

in October, 1981, one month after the District Court

struck down the "65-35 plan." It was charged with the

task of reviewing various desegregation plans and evaluat

ing which ones could work. Tr. 297.

19

RETURN TO ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE # BY

JACK GREENBERG AND JAMES M. NABRIT, III,

AND MOTION FOR WBW0W LEAVE TO WITHDRAW AS

COUNSEL FOR ###### APPELLANTS.

In response to the Order to Show cause entered herein on

January, 1983, Jack Greenberg and James M. $##### Nabrit,III

tjoth members of the bar of this ##### court, state as follows:

Jack Greenberg serves as Director-Counsel

of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and ####

James M. Nabrit, III is the Associate Counsel of ######## that

organization. ##### In our capacities as supervisors of the

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. we on occasion

permit# our names to be signed to briefs and pleadings in

or one of its employed staff attorneys

cases where the Fund/has provided ###### ###########ft#### assistant

to the ########### lead counsel handling a case but #### where

we have "not: actively participated in the presentation of the case

l\ ---- — )

ih court, the Clark case^now before this Court neither of

(Yif&KJi/ffV '^u$ has 0 had any a c t i v e p a r t i c i p a t i o n in t h e p r e s e n t a t i o n o f th e

0 ° * -

j v t J c j ^ s e i n t h i s c o u r t o r in t h e c o u r t below during 1982 o r 1 9 8 3 .

/ Neither of us had any knowledge of the facts and

1 circumstances which may have led to a violation of this courts

p.LWhp | rules until informod. of th»=<»fe£y- January 6, 1983

when we

rules until a<£ter"we--werm informed-,

first learned of the entry of this court's show

cause order.######## , Neither of us at any time agreed to

assume responsibility for any

task in connection with the perfection or

preparation of the appeal. Ph-i-*hfl,rmnr c. fibring the period

December 7, 1982 to January 4, 1983 Jack Greenberg was outside

the United States traveling in Tndi rvnrl nthrr pnrtw n f—1'rrrrr.

dual system has long been eliminated and the Board

should be permitted to consider factors other than

racial balance in structuring an elementary attendance

6/

plan." [footnote next page]

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The District Court erred by failing to require

that the school district discharge its affirmative

obligation to disestablish the dual school system and

to provide the most effective desgregation possible.

Permitting the school district to resegregate four

elementary schools as black schools was neither neces

sary nor justified and constitutes a failure of the

schools district's affirmative obligation to provide

an effective desegregation remedy. Likewise, per

mitting segregative student classroom assignment,

faculty assignment and school abandonment and con

struction also does not comport with affirmative ob

ligations to disestablish a segregated school system

now.

20

ARGUMENT

Although this case and its predecessor, Cooper v.

Aaron, span over a quarter of a century, during the great

majority of that time no significant desegregation

occurred.

When this case was before the Court in 1971 the Court

noted with respect to the elementary schools that

In the 1970-71 school year, more than seventy-

five percent of the black students attended

twelve schools which were either totally black

or more than ninety percent black, and more

than seventy-five percent of the white students

attended eleven elementary schools which were

either all-white or more than ninety percent

white.

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock, Arkansas, 449

F .2d 493, 498 (1971). Not until the 1973-74 school year

was a meaningful desegregation plan implemented. That

plan was implemented pursuant to a moratorium agreement

between the parties under which appellants made some

concessions with the hope that the School Booard, un-

6/ Plaintiffs Motion for Stay Pending Appeal and Expe

dited Appeal was denied by this Court on August 16, 1982

and the Court set a briefing schedule for this Appeal.

However, the Court directed the District Court to hold a

prompt hearing on a motion for further relief and certain

discovery requests filed by plaintiffs. The District

Court filed a Memorandum & Order on September 3, 1982, in

which it ruled that there were no unresolved motions

before the Court.

21

fettered by continuous litigation, would pursue desegregation

on its own initiative with their cooperation. That hope

proved illusory. During the period formal litigation was

held in abeyance, the uncontradicted record demonstrates that

the District engaged in segregatory and discriminatory

student assignment, faculty assignment and school closing and

construction policies which substantially vitiated the

desegregation plan. Indeed, action by the District Court was

required to prevent implementation of the segregatory

"65-35" student assignment program.

The District Court, therefore, wholly erred in

concluding that "the Little Rock School District has

operated in compliance with court decrees for nine years

as a completely unitary desegregated school system...."

Memorandum and Order of July 9, 1982, p. 16. The District

Court erroneously ignored the uncontradicted record that

any significant desegregation came late to Little Rock,

and that the task of eliminating all vestiges of

state-imposed discrimination has not yet been completed.

See, e.g. Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S.

449, 459-63 (1979). Clearly, there was no basis for any

conclusion that a unitary school system was being operated.

Martin v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

475 F. Supp. 1318, 1322-40 (W.D.N.C. 1979), aff'd on

other grounds, 626 F.2d 1165 (4th Cir. 1980), cert.

denied, 450 U.S. 1041 (1981). Even assuming arguendo,

22

black school children cannot be squared with the Constitu

tion's prohibition of racially discriminatory state

action. Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, supra,

443 U.S. at 961-63.

that the District Court's statements concerning unitariness

had some basis, resegregation of substantial numbers of

I.

The Duty of Defendant School Board and the

District Court Was "'To Come Forward With

A Plan That Promises Realistically To Work ...

Now ... Until It Is Clear That State-Imposed

Segregation Has Been Completely Removed."' 1_/

"The objective today remains to eliminate from the

public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segregation."

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U.S. 1, 15 (1971). "In default by the school authorities

of their obligations to proffer acceptable remedies, a

district court has broad power to fashion a remedy that

will assure a unitary system." Ic3. , at 16.

"Having once found a violation, the district

judge or school authorities should make every

effort to achieve the greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation, taking into

account the practicalities of the situation.

A district court may and should consider the

use of all available techniques including

restructuring of attendance zones and both

contiguous and non-contiguous attendance

zones.... The measure of any desegregation

plan is its effectiveness."

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners, 402 U.S. 33, 37

(1971 ) .

]_/ Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 4 0 2

U.S. 1, 13 (1971), quoting Green v. County School Board,

391 U.S. 431, 439 (1968) (emphasis in original).

23

The principles set forth in Swann and Davis have not

lost vitality. In 1979 the Supreme Court reiterated

that a "[school] board's continuing obligation was '"to

come forward with a plan that promises realistically to

work ... now ... until it is clear that state imposed

segregation has been completely removed."' Swann v .

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 13

(1971), quoting Green, supra at 439 (emphasis in original)."

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459

(1979); Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S.

526, 538 (1979). The Supreme Court affirmed in Penick,

that" [t]he Board's continuing 'affirmative duty to

disestablish the dual school system' [is] beyond question."

443 U.S. at 460.

Where a racially discriminatory school

system has been found to exist, Brown II imposed

the duty on local school boards to "effectuate

a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system." 349 U.S. [294] 301. "Brown II

was a call for the dismantling of well-entrenched

dual systems," and school boards operating such

systems were "clearly charged with the affirmative

duty to convert to a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root

and branch." Green v. County School Board, 391

U.S. 430, 437-438 (1968). Each instance of a

failure or refusal to fulfill this affirmative

duty constitutes the violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Dayton I, 433 U.S. at 413-414. Wright

v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451, 460

(1972); United States v. Scotland Neck Board of

Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972) (creation of a new

school district in a city that had operated a dual

school system but was not yet the subject of

court-ordered desegregation).

24

443 U.S. at 458 (emphasis added). The duty of a school

board to provide effective nondiscriminatory relief was

once again recognized. As the Court stated in the Brinkman

opinion:

Part of the affirmative duty imposed by our

cases, as we decided in Wright v. Council of City of

Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972), is the obligation

not to take any action that would impede the process

of disestablishing the dual system and its effects.

See also United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972). The Dayton Board,

however, had engaged in many post-Brown I actions

that had the effect of increasing or perpetuating

segregation. The District Court ignored this com

pounding of the original constitutional breach on the

ground that there was not direct evidence of continued

discriminatory purpose. But the measure of the

post-Brown I conduct of a school board under an

unsatisfied duty to liquidate a dual system is the

effectiveness, not the purpose, of the actions in

decreasing the segregation caused by the dual system.

Wright, supra, at 460, 462; Davis v. School Comm'rs

of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 229, 243 (1976). As was

clearly established in Keyes and Swann, the Board

had to do more than abandon its prior discriminatory

purpose. 413 U.S. at 200, 201, n.11; 402 U.S. at

28. The Board has had an affirmative responsibility

to see that pupil assignment policies and school

construction and abandonment practices "are not

used and do not serve to perpetuate or re-establish

the dual school system," Columbus, ante, at 460,

and the Board has a "'heavy burden'" of showing

that actions that increased or continued the effects

of the dual system serve important and legitimate

ends. Wright, supra, at 467, quoting Green v.

County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 439 (1968).

443 U.S. at 538 (emphasis added).

The District Court wrongly ignored the principles

of Swann and Davis which were reiterated in Brinkman and Penick.

(Indeed, Brinkman or Penick were neither cited nor re

ferred to by the lower court.) Instead, the Court allowed

implementation of "Partial K-6" because it concluded "that

the Board is not motivated by a desire to resegregate the

25

schools in adopting "Partial K-6". Memorandum and Order

of July 9, 1982, at 12. Good faith, however, is not a

defense. Id. Indeed, "the availability to the board of

other more promising courses of action may indicate a

lack of good faith." Green, supra, 391 U.S at 439.

II.

The District Court Wrongly Approved Partial K-6,

Which Unconstitutionally Resegregates Substantial

Numbers of Black School Children and Failed to

Correct Student Assignment, Faculty Assignment, and

School Closing and Construction Problems.

The District Court, cited Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S.

717, 740-741 (1974); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 22-25; and Pasadena City

Board of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 434 (1976),

for the proposition that "there can be no serious claim

that 'racial balance' in the public schools is constitu

tionally mandated." Memorandum and Order of July 9, 1982 at

17. The District Court went on to declare that

A small number of one-race, or virtually

one-race, schools within a district is not in

and of itself the mark of a system that still

practices segregation by law. Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, at 26.

This is particularly true where, as here, the

one race schools are the product of demographics

over which the Board has no control. Pasedena

City Board of Education, supra at 436. ...

Neighborhood schools, a magnet school, financial

considerations, and the desirable aspects of a

K-6 grouping are legitimate factors which may

be considered when weighing the educational

benefits of one attendance plan against another.

Id., at 17.

26

The District Court's interpretation of the case

law is tortured, however, and flies in the face of

the Supreme Court's decisions in Penick, supra, and

Brinkman. Moreover, the District Court's opinion ignores

the law of this case. While Milliken, Swann and Pasadena

all support the proposition that strict racial balance at

every school is not constitutionally required, the

Supreme Court has approved the use of mathematical

ratios and has stated that "[a]wareness of the racial

composition of the whole system is likely to be a useful

starting point in shaping a remedy to correct past

constitutional violations." Swann, supra, at 25; Kelley v .

Metropolitan County Board of Education, 687 F.2d 814, 817-19

(6th Cir. 1982).

And nothing in the case law relied upon by the

District Court supports the proposition that a school

board may knowingly and deliberately create segregated

schools. To the contrary, the governing principle is

that

in a system with a history of segregation the

need for remedial criteria of sufficient

specificity to assure a school authority's

compliance with its constitutional duty warrents

a presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in their racial

composition. Where the school authority's

proposed plan for conversion from a dual to a

unitary system contemplates the continued

existence of some schools that are all or

predominantly of one race, they have the burden

27

of showing that such school assignments are genuinely nondiscriminatory. The court should

scrutinize such schools, and the burden upon

the school authorities will be to satisfy the

court that their racial composition is not the

result of present or past discriminatory action

on their part.

Swann, supra, at 26; Kelley, supra.

Swann spoke to instances where, through circum

stances totally beyond the board's control, a school

board is simply unable to desegregate every school in a

system, and the failure to do so does not perpetuate

discriminatory state action. This case does not present

one of those instances. Rather, it presents a situation

where all of the schools in the school district were

desegregated, i ,e. , within a reasonable variation from

the district wide racial ratios before the implemen-

8/tation of Partial K-6. This is not an example of

a school board's inability to desegregate a small number

of remaining all black schools in a system; it is an

example of a school board affirmatively acting to reestab-

9/lish all black schools.

8/ Indeed, every witness to whom the question was put,

including members and employees of the School Board,

testified that under the plan in effect prior to imple

mentation of "Partial K-6", the four schools, Mitchell,

Ish, Rightsell and Carver were desegregated, as were the

rest of the Little Rock public schools. Tr. 60, 66, 89,

165, 239, 253, 436.

9/ Although the District Court refused to find that the

school board was acting discriminatorily, the uncontro

verted evidence reveals otherwise. It is beyond dispute

that the School Board knowingly and deliberately created

four virtually all black schools. See Tr. 94, 272, 395.

In fact, Mrs. Betty Herron, a School Board member, during

28

The School Board has advanced, and the District

Court has credited, a number of reasons for implementing

"Partial K-6". None of these reasons justify intentional

ly resegregating part of the School District. The phenom

enon known as "white flight" is constitutionally unaccept

able as an excuse. Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391

U.S. 450, 459 (1968); United States v. Scotland Neck City

Board of Education, 407 U.S. 484, 491 (1972); Higgins v.

Board of Education, 508 F.2d 779, 794 (6th Cir. 1974).

United States v. Board of Commissioners of Indianapolis,

Indiana, 503 F.2d 68, 80 (7th Cir. 1974). Moreover, the

presence of other non-racial reasons for adopting "Partial

K-6" does not cure the constitutional violation. Race

need not be the dominant or primary purpose behind the

School Board's actions. It is enough for equal protection

purposes, that a discriminatory purpose has been a

9/ continued

the June 7-8, 1982 hearings in the District Court,

testified that "I did not intend in reorganizing the

school district to maintain integration at this time, but

that is what I saw as something that had to be done."

Tr. 168.

The School Board's motivation for adopting "Partial

K-6" can in no way be said to be non-racial. The entire

context of the Board's actions was racial. Thus, for

racial reasons, the School Board adopted a plan with the

forseeable result of creating four virtually all-black

schools. Adherence to a particular policy or practice

"with full knowledge of the predictable effects of such

adherence upon racial imbalance in a school system is one

factor among many others which may be considered by a

court in determining whether an inference of segregative

intent should be drawn." Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, supra, 443 U.S. at 465.

29

motivating factor. Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Corporation, 429 U.S. 252, 265 (1977).

With respect to student assignment, faculty assign

ment, and school closings and construction, the

District Court found no vestiges of discrimination in

the School Board's policies or practices by wholly

ignoring the uncontroverted testimony in the record.— /

In spite of the unrebutted testimony of both employees

and non-employees of the School District to the effect

that the School Board discriminatorily and without

legitimate educational justification tracks students into

racially segregated classes, the District Court found

that "there is absolutely no evidence that [such segrega

tion is] the product of any discriminatory policy or

practice pursued by the Board." Memorandum and Order

of July 5, 1982, at 14. That conclusion is contrary to

all authority, where, as here, the board fails to

present any evidence that the assignment method is not

based on the present results of past segregation or

provides substantial educational benefits. United States

v. Gadsen Cty School Dist., 572 F.2d 1049 (5th Cir.

1978); McNeal v. Tate, 508 F.2d 1017 (5th Cir. 1975) (and

cases cited). The District Court erred when it failed to

recognize that "[pjupil assignment alone does not

10/ See Tr. 112, 114, 115, 320, 324, 402.

30

automatically remedy the impact of previous, unlawful

educational isolation, the consequences linger and can

only be dealt with by independent measures." Milliken v.

Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 287 (1977) (Milliken III). In a

system with this history of past discrimination, it

simply cannot be maintained that the classroom segrega

tion and disparities in achievement levels are not

vestiges of a dual system of segregation.

Similarly, the District Court erroneously ignored

the impact of school construction and abandonment policies.

The construction of new schools and the

closing of old ones are two of the most important

functions of local school authorities and also two

of the most complex.... In the past, choices in this

respect have been used as a potent weapon for

creating or maintaining a state-segregated school

system. In addition to the classic pattern of

building schools specifically for Negro or white

students, school authorities have sometimes, since

Brown, closed schools which appeared likely to

become racially mixed through changes in neighbor

hood residential patterns. This was sometimes

accompanied by building new schools in the areas of

white suburban expansion furthest from Negro popu

lation centers in order to maintain the separation

of the races with a minimum departure from the

formal principals of "neighborhood zoning." Such a

policy does more than simply influence a short-run

composition of the student body of a new school. It

may well promote segregated residential patterns

which, when combined with "neighborhood zoning,"

further lock the school system into the mold of

separation for the races. Upon a proper showing a

district court may consider this in fashioning a remedy.

Swann supra, 402 U.S. at 20-21; Penick, supra, 443 U.S. at

460.

The same is true of faculty assignment. Swann, supra,

402 U.S. at 18; Penick, supra, 447 U.S. at 460.

31

CONCLUSION

The judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN W. WALKER

RALPH WASHINGTON

1191 First National Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

BILL LANN LEE

THEODORE M. SHAW

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W. A. BRANTON, JR.

Suite 500

666 Eleventh Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

32

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

Undersigned counsel hereby certifies that on the 4th day

of January, 1983, copies of the foregoing Brief for Plaintiffs-

Appellants were served on attorneys for defendants-apellees

by Federal Express, guaranteed next day delivery, addressed

to:

Chris Heller, Esq.

First National Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Walter Paulson, Esq.

First National Building

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

)

I

*